Abstract

Highly responsive teachers tend to foster behaviors that are low in conflict and high in prosociality, among their students, leading to a positive classroom climate and to a decrease in bullying victimization. However, little is known about the interaction between teacher responsiveness and both student–teacher, and student–student relationship characteristics, in influencing students’ bullying victimization at school. Here, we examined student–teacher relationship quality and students’ likeability among peers as predictors of in-school victimization. Additionally, we investigated the moderating role of teacher responsiveness over this link. Study sample consisted of 386 early-adolescent students (55.2% female, mean age [SD] = 12.17 [0.73]) and 19 main teachers (females, n = 14). Findings indicated that students’ exposure to victimization was positively associated with student–teacher conflict and negatively associated with likeability among classroom peers. Teacher responsiveness did not show a significant direct association with bullying victimization. However, when teachers showed high responsiveness, the strength of the association between student–teacher conflict and students’ likelihood of bullying victimization was slightly increased. The present study highlights the importance of considering the role of teacher responsiveness when modeling the link between student and teacher relationship quality and in school bullying victimization.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Victimization by school peers is a widespread phenomenon and needs to be urgently addressed (Longobardi et al. 2017; Longobardi et al. 2018; Longobardi et al. 2019; Marengo et al. 2018). Approximately, 13% of 11 to 15 year olds worldwide are victims of bullying (Craig et al. 2009) and that the prevalence of bullying victimization has increased over the past decades (Cosma et al. 2017). As regards Italy, the results of the last population-wide survey by the Italian National Institute of Statistics showed that just over 50% students aged 11 to 17 years olds report having suffered some offensive or violent episodes by other boys or girls in the previous 12 months (ISTAT 2015).

Several studies on school bullying have shown that victimization by peers can have pervasive consequences, with both short- and long-term effects on the psychological well-being of the victims of bullies (for a meta-analysis, see Schoeler et al. 2018). Recent data showed various potential psychopathological outcomes, frequently classified as externalizing symptoms such as conduct problems, delinquency, or substance use (Quinn and Stewart 2018) and internalizing symptoms such as depression and anxiety (Lee and Vaillancourt 2018).

Given the pervasiveness of bullying victimization and the severity of its consequences for students’ welfare, it is essential to investigate potential risk and protective factors, both at the individual and group levels. Among these factors is the quality of students’ relationships with individuals they spend time with at school, including not only their classroom peers but also their teachers (e.g., Elledge et al. 2016). Beyond that, certain characteristics of teachers, such as their responsiveness in interacting with the classroom, have been suggested to play a role in this process (Serdiouk et al. 2015). In the present study, we propose an investigation of the interplay between these factors facilitating the risk of students’ victimization by their school peers. In doing this, we refer to the traditional definition by Olweus (1993), in which bullying is defined as a frequent, repeated, and unjustifiable verbal, physical, and psychological aggression that involves power asymmetry between the victim and the bully. A similar, albeit more recent definition (Gladden et al. 2014), describes bullying as (1) any unwanted aggressive behavior or behaviors directed toward a victim by a peer, or group of peers, in which the (2) victim is, or is perceived to be, lower in power compared with the aggressor/s, (3) the aggression toward the victim happens one or multiple times, causing (4) physical, psychological, educational, or social harm to the victim (Gladden et al. 2014). Victimization by bullies may be direct, i.e., including face-to-face verbal or physical confrontations, or indirect, such as spreading rumors about the victim via notes or computer-mediated communication in an effort to isolate the victim (Prino et al. 2019). In the present study, we refer to bullying victimization as a broad concept, without making distinctions between different forms of aggression. In referring to a traditional definition of bullying victimization, we distinguish ourselves from a less specific definition of peer victimization, which although similar, does not entail the existence of a power imbalance between the victims and the aggressors (Hunter et al. 2007; Söderberg and Björkqvist 2020).

Concerning the risk factors of bullying victimization, previous findings have highlighted the importance of the students’ likeability among peers, intended as a measure of peer acceptance related to the extent to which peers “like” or “dislike” a classmate or a person in a social group (e.g., their “social status, Manring et al. 2017; Wentzel 2003). Victims of bullying tend to be less liked than bully aggressors and bystanders, and they are more likely to experience rejection by peers (de Bruyn et al. 2010). Specifically, victims seem to be at the bottom of the social ranking. They are characterized by a low-level social status and likeability among peers (de Bruyn et al. 2010), although the impact of bullying victimization on likeability and acceptance among peers may vary depending on the characteristics of both the victim and the perpetrator of the aggression (e.g., gender differences, Veenstra et al. 2010). Overall, it is widely accepted that a strong association exists between various interpersonal problems, such as negative friendship quality, peer rejection, low peer acceptance and having few friends, and the risk of being victimized by peers (Hawker and Boulton 2000).

Previous studies also found that the quality of the student–teacher relationship may play a crucial role in reducing the risk of victimization by bullies (Camodeca and Coppola 2019; Iotti et al. 2020; Longobardi et al. 2018; Marengo et al. 2018). According to the attachment perspective on student–teacher relationships (Pianta 1999), teachers represent a “secure base” that may provide positive relational models, characterized by closeness and support. These models can compensate for previous experiences of insecure attachment (Longobardi et al. 2016; Longobardi et al. 2019; Marengo et al. 2019; Prino et al. 2019; Quaglia et al. 2013). In turn, several studies showed that a correlation exists between conflictual student–teacher relationships and an increased risk of school bullying among students (Elledge et al. 2016; Longobardi et al. 2018; Marengo et al. 2018). Thus, it could be argued that the student–teacher relationship could represent either a risk factor or a protective factor for bullying victimization, depending on the quality of the relationship. Findings indicate that a student–teacher relationship characterized by a low level of conflict and a high level of closeness and sensitivity tends to promote increased prosocial behavior and lowered aggressive behavior among students (Jungert et al. 2016; Longobardi et al. 2018; Marengo et al. 2018), as well as reduced internalizing and externalizing symptoms, and increased academic commitment (Hamre and Pianta 2001; Longobardi et al. 2016; Longobardi et al. 2019; Marengo et al. 2019; Prino et al. 2019). Most importantly, it generally promotes a positive classroom climate (Hamre and Pianta 2001), and increases acceptance and likeability among peers (Hendrickx et al. 2016), and plays a role in buffering the link between low peer acceptance and victimization by school peers (Elledge et al. 2016). Through the interaction with the teacher, students may internalize a positive relational model that can be reiterated in other contexts and in peer relationships (Marengo, et al. 2019). In contrast, a negative student–teacher relationship characterized by conflict compromises teachers’ ability to promote and carry out the aforementioned functions. An unsupportive and conflictual student–teacher relationship can result in an increased risk of victimization among potentially at-risk students. Indeed, faced with this type of relationship, teachers may feel less motivated to act in adolescents’ victimization episodes. As a result, they could be less effective in supporting the development of coping and conflict management skills of the student (Elledge et al. 2016).

Among the key factors promoting a positive student–teacher relationship is the ability of the teacher to foster responsive and sensitive interactions in the classroom (e.g., Baroody et al. 2014). Teacher responsiveness can be defined as the ability to provide students with emotional support (e.g., providing comfort, warmth) and to meet students’ needs as individual learners by providing sensitive and timely instructional and organizational support (Walker and Hoover-Dempsey 2015). Responsive teachers promote students’ academic achievement and behavior (Hamre and Pianta 2001), engagement (Furrer and Skinner 2003), academic motivation (Ryan et al. 1994) and prosocial behavior (Birch and Ladd 1998). Teachers who demonstrate an emotional connection to students and teachers who are responsive to students’ needs may offer a positive model of relational skills, crucial for a positive peer relationships and, at the same time, they could establish a climate where positive peer relationships can flourish (Gest and Rodkin 2011). As such, classrooms with teachers who are sensitive and supportive to students’ needs have been shown to be characterized by lower levels of bullying (e.g., Wei et al. 2010), higher levels of prosocial behavior (Luckner and Pianta 2011) and less rejection of withdrawn children (Chang et al. 2007), as well as overall more positive student–teacher relationship quality (e.g., Marengo et al. 2019).

Shell et al. (2014) found evidence of a link existing between a decrease in the teacher responsiveness in providing emotional support, and an increased victimization in the transition from primary to middle school. Similarly, Braun et al. (2019) found evidence of significant positive associations between teacher responsiveness score and students’ perceptions of their classroom peers as less aggressive, and more prosocial. In turn, Serdiouk et al. (2015) found that teacher responsiveness was not directly associated with in-school victimization in the sample of primary school students. Although many studies exist concerning the association between teacher responsiveness and victimization by school peers, findings concerning the role of responsive teachers in buffering the effect of individual student characteristics as factors in in-school bullying victimization are scarce and inconclusive (e.g., Serdiouk et al. 2015). As noted above, the quality of students’ relationship with their peers and teachers is expected to have an influence on their likelihood to be involved in victimization at school (e.g., de Bruyn et al. 2010; Elledge et al. 2016; Longobardi et al. 2018; Marengo et al. 2018). It is reasonable to expect that differences in teachers’ responsiveness in managing classroom interactions might be related to the ability to buffer the effect of these characteristics as facilitators of students’ victimization by school peers.

In light of these considerations, with the present study, we aim to investigate the links between teacher responsiveness, self-reported student–teacher relationship quality (i.e., closeness and conflict), students’ likeability among their classroom peers (operationalized via sociometric social preference), and students’ risk of in-school bullying victimization in early adolescence. Extending previous studies, we examine teacher responsiveness as a moderator of the links between student–teacher closeness and conflict, and likeability among classroom peers, and the likelihood of being bullied by school peers. In exploring these effects, we also control for the effects of age and gender. According to the literature, gender and age are generally observed to play a role in the risk of bullying victimization (e.g., Ettekal and Ladd 2017; Longobardi et al. 2019; Marengo et al. 2019; Prino et al. 2019), therefore we control for these variables in exploring these effects. Based on the existing findings, we hypothesize that student–teacher relationship high in conflict might be related to an increase of the risk of bullying victimization. In turn, we expect that student–teacher closeness and likeability among classroom peers might protect student from the risk of victimization by classroom peers. As regards the investigation of the role of teacher responsiveness, because of the scarcity and mixed nature of previous findings, our aim is mostly exploratory.

Method

Procedure and sample

We recruited a convenience sample consisting of 412 lower-secondary (grades 6–8) students clustered in 20 classrooms in four public schools from urban areas in Northern Italy. We also recruited students’ main teachers (N = 20)—i.e., teachers who spend the highest amount of weekly lesson time in the classroom. It is worthy to note that in the Italian school system, it is typical for main teachers to teach to the same group of students from grades 6 to 8. Students change their main teacher and classroom peers when they progress to the next school level (e.g., when transitioning from lower-secondary school to high school). Participation in the research involved a series of observational classroom assessments conducted by trained observers using the Classroom Assessment Scoring System (CLASS). Additionally, students and teachers completed a set of self-report questionnaires. Administration of questionnaire to students took place in the classroom under the supervision of an external observer. Prior to questionnaire administration, students were informed about the expected average administration time for all sections of the questionnaire (1 h), the possibility to quit from participating in the study at any time, and handling of collected data for privacy purposes. The teacher was not present in the classroom during questionnaire administration.

For each classroom, data collection took place at different time points during the last 4 months of school year, starting in March 2018. Observation in the classroom using the CLASS system was performed before administering questionnaires to students. Prior to data collection, we obtained written and informed consent from all students and their parents. The teachers from the participating classrooms were also asked to sign an informed consent form to take part in the study. In compliance with the ethical code of the Italian Association for Psychology, all the participants were assured of data confidentiality and of the nature and objective of the study. They were also advised that participation in the study was voluntary and that they could withdraw from the study at any time. The study was approved by the IRB of the university (protocol no. 13432).

After the exclusion of one teacher who failed to answer the questionnaire and five students with incomplete questionnaire data, the final sample consisted of 386 students from 19 classrooms, with an average number of 20.68 students per classroom (SD = 2.65), and including 55.2% female students with a mean age of 12.17 (SD = 0.73) years. As regards students’ citizenship status, 85% of students indicated being Italian citizens; a minority of students (~1%) reported having a citizenship from other countries from the European Union (EU), while the remaining students (~14%) had an extra-EU citizenship. As regards students’ average academic achievement, based on the Italian grades system for the secondary school, in which grades range from 1 (extremely poor) to 10 (excellence), and 6 indicates passing (sufficiency), the average of students’ grades in the sample was 7.47 (SD = 1.26).

This final sample included 19 teachers, of which n = 14 females, and n = 5 males, with a mean age of 54.89 (SD = 5.70) years, with an average teaching experience of 22.84 (SD = 9.01) years. At the time of recruitment, on average, the teachers had been teaching in the same classroom for 1.61 (SD = 0.98) years, spending on average 8.11 (SD = 2.51) h with the same students in a typical school week.

Instruments

Bullying victimization

Students’ involvement in bullying victimization was assessed using a version of the Olweus Bully/Victim Questionnaire (Olweus 1993) adapted for use in an Italian school (Genta et al. 1996). In the questionnaire, a definition of bullying was provided to students in order for them to have a clear understanding of what they were expected to rate. In the definition, a victimization event was described as involving physical (e.g., “when a child is hit, kicked, threatened, locked inside a room”), verbal (“when another child, or a group of children, say nasty and unpleasant things to” the victim), or relational types (e.g., “when no one ever talks to” the victim) of aggression involving a power imbalance between the victim and the bully, and a repetition in time. A full transcript of the definition provided to students in the questionnaire is reported in Genta et al. (1996).

The participants were asked to rate their frequency of bullying victimization via the following target question: “How often have you been bullied at school in the past couple of months?” The students could rate the frequency of victimization using the following response categories: “It hasn’t happened to me in the past couple months,” “Only once or twice”, “About once a week,” or “Several times a week”. Students who answered “only once or twice” or more to the target question were considered victims of school bullying. We used this scoring approach (also called the “at-least-once” criterion) to identify school victims, as it is expected to have the strongest convergent validity with other observant-based approaches (e.g., peer nominations) ( Lee and Cornell 2009). Test–retest reliability of the questionnaire is known to be satisfactory (Genta et al. 1996; Olweus 1997). Based on this approach, we created a dichotomous variable by coding as 1 the 87 (22.5%) students that reported being victims of bullying by school peers in the previous couple of months, and coding 0 the remaining 299 (77.5%) students who did not report being involved in bullying events. The prevalence rate was similar to that reported by previous findings using the same questionnaire in the Italian context (e.g., Genta et al. 1996; Nocentini and Menesini 2016).

Teacher responsiveness

Teacher responsiveness was assessed using the Italian version of the CLASS (Pianta et al. 2008; Longobardi et al. 2020). The CLASS is an observational assessment performed by trained observers over the course of a series of classrooms which can be used to assess different aspects of teachers’ interaction with their classroom, including emotional and instructional support to students, as well as an organizational component of teachers’ responsiveness and a global teacher responsiveness score. More specifically, using the CLASS, 10 components of teachers’ interactions with the students in the classroom were scored on a Likert scale ranging from 1 to 7, namely, a positive climate, a negative climate, teacher sensitivity, regard for student perspective, behavior management, productivity, instructional learning formats, concept development, quality of feedback, and language modeling. For more information on the constructs assessed by CLASS observational system, see Pianta et al. (2008).

For the purpose of the present study, assessment was performed by six (n = 6) observers. Prior to performing the observations, the observers attended a 40-h training including a 12-h preparatory training on CLASS characteristics (e.g.., dimensions, and coding criteria), and a series of sessions including group and individual coding practice conducted using videos of classroom activities until an 80% interrater agreement was achieved (Pianta et al. 2008). In each classroom, the observers underwent six 20-minute observations, using notes to record specific events related to each CLASS dimension, followed by a coding session taking place in the 10 min following the observation. The six observations were carried out at different times of the day and week to capture the teacher’s different activities with the class and to compensate for possible tiredness due to the end of the day or week. The classes were observed over a period of three months. Observations were performed as planned in all the participating classes, and no data were missing.

Scoring the CLASS system traditionally requires combining the observers’ coding of the 10 components to form three domain scores: emotional support, instructional support, and classroom organization. Due to the strong correlations between these three CLASS dimensions, they are expected to share a large portion of common variance, suggesting the existence of a general teacher responsiveness dimension explaining most of the variance in collected data (Longobardi et al. 2020). For this reason, recent studies have proposed an alternative scoring procedure based on confirmatory factor analysis (i.e., a scoring procedure based on a bifactor model) (e.g., Hamre et al. 2014; Longobardi et al. 2020). Using the bifactor approach, the 10 components are allowed to load both on a general factor and on domain-specific scales, which are modeled as orthogonal. For the purpose of this study, we employed the bifactor modeling procedure proposed by Longobardi et al. (2020) to obtain a single indicator of teaching responsiveness. More specifically, using the approach of Longobardi et al. (2020) and the collected CLASS data, for each teacher we computed factor scores for the general factor of “teacher responsiveness”. The score showed high score reliability (MacDonald’s ω = .94).

Student–teacher relationship quality

The quality of the student–teacher relationship was assessed using the Student Perception of Affective Relationship with Teacher Scale (Koomen and Jellesma 2015). This scale consists of 25 items investigating three dimensions of student–teacher relationships from the point of view of the student, namely, closeness, conflict, and negative expectations. Students were instructed to answer the questionnaire items thinking about their current relationship with the main teacher of the classroom. For the purpose of the present study, we administered the closeness scale (8 items), which assesses students’ positive feelings toward and reliance on their teacher (e.g., “I feel most at ease when my teacher is near,” “When I feel uncomfortable, I go to my teacher for help and comfort,” and “I think I have a good relationship with my teacher”), and conflict scale (10 items). The latter refers to students’ perceptions of the extent of their negative behavior and their teachers’ attitudes toward them (e.g., “I guess my teacher gets tired of me in class,” “I quarrel easily with my teacher,” and “I feel my teacher doesn’t trust me”). The 18 items are answered using a 5-point response scale, ranging from 1 (“no, that is not true”) to 5 (“yes, that is true”). The scales showed adequate score reliability (Closeness: MacDonald’s ω = .82; Conflict: MacDonald’s ω = .78).

Students’ likeability among classroom peers

Each participant’s likeability among classroom peers was assessed using a sociometric approach. Specifically, we used a peer nomination questionnaire inspired by Moreno’s (1934) sociogram techniques and the sociometric strategy of Coie et al. (1982) to assess students’ statuses among their classroom peers. The administered questionnaire consisted of six questions (three positive and three negative) requiring the students to nominate three of their peers. The questions were as follows: (a) “Who would you want as a table partner?,” (b) “Who would you want as a schoolwork partner?,” (c) “Who would you want as a field trip buddy?,” (d) “Who would you NOT want as a table partner?,” (e) “Who would you NOT want as a schoolwork partner?,” and (f) “Who would you NOT want as a field trip buddy?.” To obtain an indicator of the students’ statuses in the classroom, we followed the sociometric strategy proposed by Coie et al. (1982) by combining the number of positive and negative nominations received by each student and producing a single indicator of the student’s status in the classroom ( i.e., the social preference score). For each student, we computed the average of the positive nominations received from all their peers (“liked most” [LM] scores), and the average of the negative nominations received by each student (“liked least” [LL] scores). The LL and LM scores were then transformed to standard scores by classroom (ZLM, ZLL scores). As a final step, the social preference score was computed by subtracting the ZLL score from the ZLM score, thus obtaining an indicator of the status of the student among their peers. Higher social preference scores indicate greater likeability by classroom peers.

Strategy of analysis

First, we computed descriptive statistics for the study variables. Then we computed Pearson’s correlations among level-1 variables. For computing cross-level correlations between level-1 (student) variables and the level-2 teacher responsiveness score, the latter variable was disaggregated by assigning each member of the classroom the same value, thus.

Next, we investigated the presence on nonindependence in the outcome variable (i.e., bullying victimization) by computing the intraclass correlation (ICC) coefficient, and the relative design effect. A design effect > 2 is typically considered indicating the presence of nonnegligible lack of independence among clustered observations (Muthén & Satorra 1995).

Then, we performed logistic regression analyses, including student-level variables (i.e., student–teacher conflict and closeness and likeability among classroom peers) and the teacher-level teacher responsiveness variable as independent variables. A binary variable representing students’ involvement in bullying victimization (1 = victimized by school peers; 0 = not victimized) served as the model outcome. Analyses were performed using a two-step hierarchical approach. In the first step, level-1 variables (i.e., student–teacher conflict and closeness, and social preference) and the level-2 teacher responsiveness score were entered in the model as main effects; next, cross-level interaction terms between teacher-level teacher responsiveness (grand mean centered) and each of the student-level variables were entered in the model. No centering was applied to Level 1 variables. In all analyses, we controlled for the effects of student age and gender. Because of students’ clustering into classrooms, the analyses were performed using a multilevel approach. Specifically, SAS GLIMMIX Procedure was used to account for nonindependence among nested data and model the binary distribution of the victimization variable using a cumulative logit link. For the purpose of analyses using the multilevel model, the risk of bullying victimization was modeled using a cumulative logit link, with level-1 and level-2 variables included as fixed effect, and using a random intercept effect to control for the non-independence existing within the classroom. When modeling a binary outcome using logit link, the residual variance is fixed at π2/3 since the scale of the underlying latent variable is unobserved (Bauer and Sterba 2011). Therefore, only the random intercept variance was estimated, and reported in the results. The model was estimated using an RSPL estimator, and denominator degrees of freedom were calculated using the Satterthwaite (1941) method, with the Kenward–Roger adjustment (Kenward & Roger 1997). This procedure can be used to guard against inflated type-I errors due to underestimated fixed-effect standard errors when the number of clusters is small (McNeish and Stapleton 2016). Simulation studies demonstrated that the Kenward–Roger adjustment performed well, even in cases of as few as 10 clusters. In each step of the analyses, the explicative power of the model was evaluated using the pseudo-R2 approach proposed by Zhang (2017) for generalized linear models.

Results

Descriptive statistics and correlations of the study variables are presented in Table 1. In general, the size of the correlations was small to moderate. The results showed being female was negatively correlated with student–teacher conflict and positively correlated with the students’ likeability among peers. Age was negatively related to student–teacher closeness. Bullying victimization correlated positively with student–teacher conflict and showed a negative correlation with likeability among peers, and students’ age. In addition, student–teacher conflict and likeability among peers showed a negative correlation. Student–teacher conflict and closeness showed a moderate negative correlation. Finally, as regards cross-level correlations, we found classroom-level teacher responsiveness was positively related to individual-level student–teacher closeness (r = .29, p<.01) and negatively related to individual-level student–teacher conflict (r = −.23, p<.01).

As regards nonindependence in the outcome variable (i.e., victimization) due to students’ clustering in classrooms, the ICC for victimization was .04, which based on an average of 20 students per class corresponds to a design effect of 1.76, indicating that nonindependence of the victimization variable due to students’ clustering in classrooms was not high. Table 2 shows the results of the multilevel logistic models examining the impact of the association between student- and teacher-level effects and their interaction on a student’s likelihood of being a victim of school bullying. The first step of the model, including only student- and classroom-level main effects, showed that student–teacher conflict had a positive effect on bullying victimization, whereas students’ likeability among peers had a negative effect. Teacher responsiveness did not show a significant effect on student victimization. Among the control variables, being female was associated with a higher likelihood of bullying victimization. In the next step, interaction effects between student-level variables and teacher-level teacher responsiveness were included in the model. Among the included interaction effects, only the interaction between student–teacher conflict and teacher responsiveness had a significant effect on the victimization variable (p < .05).

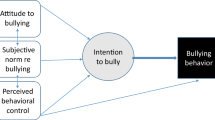

Figure 1 depicts this emerging interaction effect. This seems to suggest that when teachers showed high responsiveness (a high level of responsiveness), the effect of student–teacher conflict on students’ likelihood of being victimized by school peers increased. Thus, at medium-to-high levels of teacher responsiveness, students reporting a high conflict relationship with their teachers had an increased risk of being victimized by school peers as compared with that of students reporting low level of student–teacher conflict. At the same time, at lower levels of teacher responsiveness, student–teacher conflict had no significant effect on students’ likelihood of being victimized by school peers.

Discussion

In the present study, we investigated the interplay between variables reflecting students’ quality of relationships with their classroom peers and their teachers as well, and the ability of teachers to be responsive in managing the classroom, in influencing the risk of involvement in in bullying victimization. In particular, we investigated the associations between students’ conflict and closeness with their teachers, students’ likeability among classroom peers (i.e., peer-reported social preference) and bullying victimization, and explored the role teachers’ responsiveness as a moderator of these links, while controlling for students’ age and gender. Using a multilevel analytical approach, we found that the risk of bullying victimization was positively related to student–teacher conflict, and negatively associated with students’ likeability among peers. As regards teacher responsiveness, we failed to identify a direct association with bullying victimization; however, we found evidence that teacher responsiveness had a small moderating effect on the link between student−teacher conflict and students’ risk of bullying victimization.

Overall, these findings are consistent with several studies demonstrating that student–teacher relationships, characterized by conflict, are associated with an increased risk of bullying victimization (Elledge et al. 2016; Longobardi et al. 2018; Marengo et al. 2018). In the case of a low-quality relationship, a teacher may be less motivated to handle episodes of victimization toward a child and may be less effective in supporting the development of effective coping and conflict management skills (Elledge et al. 2016). Furthermore, it is important to underline that teacher behaviors toward individual students could also reflect teacher’s (dis)like for the student, which, in turn, could promote peers’ (dis)like of that student, as highlighted by Hendrickx et al. (2016).

In our study, peer likeability among peers was negatively related with student–teacher conflict and bullying victimization. These findings echo those studies indicating the existence of a significant association between positive student–teacher relationship, and social acceptance at school (Hendrickx et al. 2016), as well as studies showing that victims of bullying tend to be low in popularity among peers, and vice versa (Card and Hodges 2008; de Bruyn et al. 2010).

As regards teacher responsiveness, results of correlations highlighted a positive association with individual-level student–teacher closeness, and a negative association with student–teacher conflict. These findings are coherent with literature indicating teachers’ responsiveness and sensitivity in managing classroom interactions as a key factor in promoting a positive classroom climate, and relationship quality with their students (e.g., Longobardi et al. 2020). However, since they are based on cross-level correlations, and we could only recruit a low number of classrooms, robustness of these findings is limited. Studies employing larger samples may help provide a clearer view on these associations.

Our finding on the association between teaching responsiveness and bullying victimization is partially unexpected, adding to existing mixed results concerning this link (Serdiouk et al. 2015). In our study, we failed to find a direct association, but we found evidence of a small, marginally significant effect indicating teacher responsiveness as a moderator of the link between student–teacher conflict, and bullying victimization. More specifically, we found that at a medium-to-high level of teacher responsiveness, student–teacher conflict was associated with increased bullying victimization, while at low levels of teachers’ responsiveness, the effect was not significant. In other words, when student–teacher conflict is low, students’ likelihood of bullying victimization is always low, regardless of the level of teacher responsiveness. In turn, students whose relationship with conflictual relationship with their teacher are more exposed to bullying victimization when a highly responsive teacher leads the classroom. Possible interpretations for this surprising finding relate to existing positive associations between teacher responsiveness and positive student–teacher relationship quality (e.g., Longobardi et al. 2020), and the interplay existing between student-relationship quality, likeability among peers, and lowered risk of bullying victimization (Hughes and Chen 2011). Student–teacher conflict may facilitate bullying victimization because teacher may be less proactive in monitoring or defending the student, and thus potential aggressors might feel more inclined to pursue the aggression as they feel they are less likely to be punished. Additionally, student with conflictual relationship with teachers tend to be less liked by their peers, which in turn is related to an increase in the risk of bullying victimization. It is then possible that students who share a highly conflictual relationship with a teacher who is generally highly responsive to other students, may be more likely to be exposed to victimization because of increased peer disliking, or alternatively, heightened neglect by the teacher, suggesting the presence of underlying moderated mediation processes. A recent study found evidence in support of a similar mediation process (Smeraglia 2017). For the purpose of the present study, however, because we relied on cross-sectional data, we could not investigate mediation process potentially linking the investigated constructs. Additionally, sample size for the study was small, limiting robustness of findings, especially for what concerns generating inferences at the teacher level. Longitudinal studies might help understand the nature of the process linking teacher responsiveness, student–teacher relationship quality, and exposure to victimization at school.

Finally, as regards students’ demographic characteristics, results were mostly in support of existing literature. Being female was positively correlated with likeability among peers. This finding is in line with that of an analysis conducted by Manring et al. (2017) in which girls were more socially preferred than boys. In our study, female were also less likely to report student–teacher conflict. A possible explanation for this finding could be that girls are more likely than boys are to give priority to affection and to the development of intimate relationships (Caravita and Cillessen 2012). Indeed researchers also showed that girls tended to form closer and less conflicted relationships with teachers when compared with those formed by boys (e.g., Hamre and Pianta 2001). We also found a positive link between being female and exposure to victimization, which we interpret as a consequence of the gradual shift, in early adolescence, from physical victimization, which is generally more prevalent among boy, toward relational victimization, which instead is expected to be more prevalent among girls (for a review, see Ettekal and Ladd 2017). Because the assessment of victimization employed in the present study does not provide separate scores for different types of victimization (physical, verbal, and relational), we could not examine this effect further.

Age was negatively associated with student–teacher closeness. According to the literature, both closeness and conflict decrease over time in the early years of school (Pianta and Stuhlman 2004). After children enter middle school, class sizes increase, and the students spend less time with their teachers. Consequently, student–teacher relationships become less close, and more impersonal (Jerome et al. 2009). We also found indication of small negative association between age and bullying victimization, which is coherent with literature indicating a decline in bullying as students transition from childhood to adolescence (e.g., Marengo et al. 2019).

Limitations and conclusions

Although the findings from the present study are largely in line with existing literature (Espelage et al. 2003; Chang et al. 2007; Wei et al. 2010; Hughes and Chen 2011; Luckner and Pianta 2011; Longobardi et al. 2018; Marengo et al. 2018; Camodeca and Coppola 2019), they also suffer from some limitations. First, a longitudinal study design would have been more appropriate to capture both the temporal evolution and dynamic essence of student–teacher relationships. Because of the lack of longitudinal data, the identified associations should be viewed with caution. Future longitudinal studies may help us to better understand the direction of the effects. Second, because we used a convenience sampling strategy, and participants consisted of early adolescents from Italy, care is needed in generalizing our findings to the reference population, both within and outside the cultural context in which the data was collected. Finally, use of self-report measures which are vulnerable to social desirability bias and might have inflated associations due to shared method variance. Despite these limitations, this study also has a number of strengths, such as the use of a large sample and multiple informers (e.g., students, their peers, and observers external to the classroom context), limiting common method biases. As such, the study advances understanding of the complex interplay existing between student- and teacher-level indicators of the quality of classroom interactions, and students’ exposure to victimization during early adolescence.

Practical implications and future directions

Combined with existing literature, the findings from the present study may have practical implications for classroom-level interventions. In particular, there exists now convincing evidence concerning the association between concurrent associations between student–teacher conflict, peer dislike, and bullying victimization. In particular, at the teacher level, interventions should aim at generating awareness concerning the long-lasting, negative effect that persisting negative student–teacher relationships may have on students’ well-being, and how this effect may link to a general worsening of students’ standing among their classroom peers. Additionally, based on our findings, it emerges that highly responsive teaching practices may not protect students from being bullied by school peers when these students have a conflictual relationship with their teacher, but instead exacerbate their risk of victimization. Hence, teachers need to be aware of the potential adverse effects of a typically well-regarded teaching practice. Still, it is important to note that additional research is still needed to determine the role that teacher responsiveness plays in buffering risk factors at the student-level for bullying victimization. In particular, open questions remain concerning the role of student–teacher interactions in influencing student likeability and social status among peers, and how these variables relate to bullying victimization. Eventually, the role of age and gender as intervening variables could also be explored. Because we expect exposure to different types of victimization to vary in prevalence across gender and age groups, multigroup studies investing these processes would help understand existing differences, informing intervention aimed at reducing their prevalence among adolescents. Additionally, in exploring the association between teacher responsiveness, students’ likeability, and bullying victimization, future studies should address this aim by also considering the distinction between direct and indirect forms of bullying, because these are expected to differ in their association with many student variables, including those reflecting teacher–student relationship quality (Longobardi et al. 2020).

Change history

21 April 2021

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-021-00555-z

References

Baroody, A. E., Rimm-Kaufman, S. E., Larsen, R. A., & Curby, T. W. (2014). The link between responsive classroom training and student–teacher relationship quality in the fifth grade: A study of fidelity of implementation. School Psychology Review, 43(1), 69–85. https://doi.org/10.1080/02796015.2014.12087455.

Bauer, D. J., & Sterba, S. K. (2011). Fitting multilevel models with ordinal outcomes: Performance of alternative specifications and methods of estimation. Psychological Methods, 16(4), 373–390. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0025813.

Birch, S. H., & Ladd, G. W. (1998). Children's interpersonal behaviors and the teacher–child relationship. Developmental Psychology, 34(5), 934–946. https://doi.org/10.1037//0012-1649.34.5.934.

Braun, S. S., Zadzora, K. M., Miller, A. M., & Gest, S. D. (2019). Predicting elementary teachers’ efforts to manage social dynamics from classroom composition, teacher characteristics, and the early year peer ecology. Social Psychology of Education, 1-23. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-019-09503-8.

Camodeca, M., & Coppola, G. (2019). Participant roles in preschool bullying: The impact of emotion regulation, social preference, and quality of the teacher–child relationship. Social Development, 28(1), 3–21. https://doi.org/10.1111/sode.12320.

Caravita, S. C., & Cillessen, A. H. (2012). Agentic or communal? Associations between interpersonal goals, popularity, and bullying in middle childhood and early adolescence. Social Development, 21(2), 376–395. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9507.2011.00632.x.

Card, N. A., & Hodges, E. V. (2008). Peer victimization among schoolchildren: Correlations, causes, consequences, and considerations in assessment and intervention. School Psychology Quarterly, 23(4), 451–461. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0012769.

Chang, L., Liu, H., Fung, K. Y., Wang, W., Wen, Z., Li, H., & Farver, J. A. M. (2007). The mediating and moderating effects of teacher preference on the relations between students’ social behaviors and peer acceptance. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 53(4), 603–630.

Cosma, A., Whitehead, R., Neville, F., Currie, D., & Inchley, J. (2017). Trends in bullying victimization in Scottish adolescents 1994–2014: Changing associations with mental well-being. International Journal of Public Health, 62(6), 639–646.

Coie, J. D., Dodge, K. A., & Coppotelli, H. A. (1982). Dimensions and types of social status: A cross-age perspective. Developmental Psychology, 18, 557–569. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.18.4.557.

Craig, W., Harel-Fisch, Y., Fogel-Grinvald, H., Dostaler, S., Hetland, J., Simons-Morton, B., Molcho, M., Gaspar de Mato, M., Overpeck, M., Due, P., & Pickett, W. (2009). A cross-national profile of bullying and victimization among adolescents in 40 countries. International Journal of Public Health, 54(S2), 216–224.

de Bruyn, E. H., Cillessen, A. H. N., & Wissink, I. B. (2010). Associations of peer acceptance and perceived popularity with bullying and victimization in early adolescence. Journal of Early Adolescence, 30(4), 543–566. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272431609340517.

Elledge, L. C., Elledge, A. R., Newgent, R. A., & Cavell, T. A. (2016). Social risk and peer victimization in elementary school children: The protective role of teacher–student relationships. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 44(4), 691–703. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-015-0074-z.

Espelage, D. L., Holt, M. K., & Henkel, R. R. (2003). Examination of peer–group contextual effects on aggression during early adolescence. Child Development, 74(1), 205–220.

Ettekal, I., & Ladd, G. W. (2017). Developmental continuity and change in physical, verbal, and relational aggression and peer victimization from childhood to adolescence. Developmental Psychology, 53(9), 1709–1721.

Furrer, C., & Skinner, E. (2003). Sense of relatedness as a factor in children's academic engagement and performance. Journal of Educational Psychology, 95(1), 148–162. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.95.1.148.

Genta, M. L., Menesini, E., Fonzi, A., Costabile, A., & Smith, P. K. (1996). Bullies and victims in schools in central and southern Italy. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 11(1), 97–110.

Gest, S. D., & Rodkin, P. C. (2011). Teaching practices and elementary classroom peer ecologies. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 32(5), 288–296.

Gladden, R. M., Vivolo-Kantor, A. M., Hamburger, M. E., & Lumpkin, C. D. (2014). Bullying surveillance among youths: Uniform definitions for public health and recommended data elements, Version 1.0. Atlanta: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and U. S. Department of Education.

Hamre, B. K., & Pianta, R. C. (2001). Early teacher–child relationships and the trajectory of children's school outcomes through eighth grade. Child Development, 72(2), 625–638. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00301.

Hamre, B., Hatfield, B., Pianta, R., & Jamil, F. (2014). Evidence for general and domain-specific elements of teacher–child interactions: Associations with preschool children's development. Child Development, 85(3), 1257–1274. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12184.

Hawker, D. S. J., & Boulton, M. J. (2000). Twenty years’ research on peer victimization and psychosocial maladjustment: A meta-analytic review of cross-sectional studies. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 41(4), 441–455. https://doi.org/10.1111/1469-7610.00629.

Hendrickx, M. M., Mainhard, M. T., Boor-Klip, H. J., Cillessen, A. H., & Brekelmans, M. (2016). Social dynamics in the classroom: Teacher support and conflict and the peer ecology. Teaching and Teacher Education, 53, 30–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2015.10.004.

Hughes, J. N., & Chen, Q. (2011). Reciprocal effects of student–teacher and student–peer relatedness: Effects on academic self efficacy. Journal of applied developmental psychology, 32(5), 278–287. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2010.03.005.

Hunter, S. C., Boyle, J. M., & Warden, D. (2007). Perceptions and correlates of peer-victimization and bullying. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 77(4), 797–810. https://doi.org/10.1348/000709906X171046.

Iotti, N. O., Thornberg, R., Longobardi, C., & Jungert, T. (2020). Early adolescents’ emotional and behavioral difficulties, student–teacher relationships, and motivation to defend in bullying incidents. Child & Youth Care Forum, 1(49), 59–75. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-019-09519-3.

ISTAT. (2015). Annual results of italian population. Avaible at: https://www.istat.it/it/archivio/159350

Jerome, E. M., Hamre, B. K., & Pianta, R. C. (2009). Teacher–child relationships from kindergarten to sixth grade: Early childhood predictors of teacher-perceived conflict and closeness. Social Development, 18(4), 915–945. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9507.2008.00508.x.

Jungert, T., Piroddi, B., & Thornberg, R. (2016). Early adolescents' motivations to defend victims in school bullying and their perceptions of student–teacher relationships: A self-determination theory approach. Journal of Adolescence, 53, 75–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2016.09.001.

Kenward, M. G., & Roger, J. H. (1997). Small sample inference for fixed effects from restricted maximum likelihood. Biometrics, 983–997.

Koomen, H. M., & Jellesma, F. C. (2015). Can closeness, conflict, and dependency be used to characterize students’ perceptions of the affective relationship with their teacher? Testing a new child measure in middle childhood. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 85(4), 479–497. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12094.

Lee, T., & Cornell, D. (2009). Concurrent validity of the Olweus bully/victim questionnaire. Journal of School Violence, 9(1), 56–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/15388220903185613.

Lee, K. S., & Vaillancourt, T. (2018). Longitudinal associations among bullying by peers, disordered eating behavior, and symptoms of depression during adolescence. JAMA Psychiatry, 75(6), 605–612.

Longobardi, C., Gastaldi, F. G. M., Prino, L. E., Pasta, T., & Settanni, M. (2016). Examining student-teacher relationship from students’ point of view: Italian adaptation and validation of the young children’s appraisal of teacher support questionnaire. The Open Psychology Journal, 9(1). https://doi.org/10.2174/1874350101609010176.

Longobardi, C., Prino, L. E., Fabris, M. A., & Settanni, M. (2017). School violence in two Mediterranean countries: Italy and Albania. Children and Youth Services Review, 82, 254–261. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2017.09.037.

Longobardi, C., Badenes-Ribera, L., Fabris, M. A., Martinez, A., & McMahon, S. D. (2018). Prevalence of student violence against teachers: A meta-analysis. Psychology of Violence. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1037/vio0000202.

Longobardi, C., Prino, L. E., Fabris, M. A., & Settanni, M. (2019). Violence in school: An investigation of physical, psychological, and sexual victimization reported by Italian adolescents. Journal of School Violence, 18(1), 49–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/15388220.2017.1387128.

Longobardi, C., Pasta, T., Marengo, D., Prino, L. E., & Settanni, M. (2020). Measuring quality of classroom interactions in italian primary school: structural validity of the CLASS K–3. The Journal of Experimental Education, 88(1), 103–122. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220973.2018.1533795.

Luckner, A. E., & Pianta, R. C. (2011). Teacher–student interactions in fifth grade classrooms: Relations with children’s peer behavior. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 32(5), 257–266.

Manring, S., Elledge, L. C., Swails, L. W., & Vernberg, E. M. (2017). Functions of aggression and peer victimization in elementary school children: The mediating role of social preference. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 46(4), 795–809. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-017-0328-z.

Marengo, D., Jungert, T., Iotti, N. O., Settanni, M., Thornberg, R., & Longobardi, C. (2018). Conflictual student–teacher relationship, emotional and behavioral problems, prosocial behavior, and their associations with bullies, victims, and bullies/victims. Educational Psychology, 38(9), 1201–1217. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2018.1481199.

Marengo, D., Settanni, M., Prino, L. E., Parada, R. H., & Longobardi, C. (2019). Exploring the dimensional structure of bullying victimization among primary and lower-secondary school students: is one factor enough, or do we need more?. Frontiers in psychology, 10, 770. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00770.

McNeish, D. M., & Stapleton, L. M. (2016). The effect of small sample size on two-level model estimates: A review and illustration. Educational Psychology Review, 28(2), 295–314. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-014-9287-x.

Muthén, B. O., & Satorra, A. (1995). Technical aspects of Muthén's LISCOMP approach to estimation of latent variable relations with a comprehensive measurement model. Psychometrika, 60(4), 489–503.

Nocentini, A., & Menesini, E. (2016). KiVa Anti-Bullying program in Italy: Evidence of effectiveness in a randomized control trial. Prevention Science, 17(8), 1012–1023.

Olweus, D. (1993). Bullying at school: What we know and what we can do. Oxford: Blackwell.

Olweus, D. (1997). Bully/victim problems in school: Facts and intervention. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 12(4), 495–510.

Pianta, R. C. (1999). Enhancing relationships between children and teachers. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Pianta, R. C., & Stuhlman, M. W. (2004). Teacher–child relationships and children's success in the first years of school. School Psychology Review, 33(3), 444–458.

Pianta, R. C., La Paro, K. M., & Hamre, B. K. (2008). Classroom Assessment Scoring System™: Manual K-3. Paul H Brookes Publishing.

Prino, L. E., Longobardi, C., Fabris, M. A., Parada, R. H., & Settanni, M. (2019). Effects of bullying victimization on internalizing and externalizing symptoms: the mediating role of alexithymia. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 28(9), 2586–2593. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220973.2018.1533795.

Quaglia, R., Gastaldi, F. G., Prino, L. E., Pasta, T., & Longobardi, C. (2013). The pupil-teacher relationship and gender differences in primary school. The Open Psychology Journal, 6, 69–75. https://doi.org/10.2174/1874350101306010069.

Quinn, S. T., & Stewart, M. C. (2018). Examining the long-term consequences of bullying on adult substance use. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 43(1), 85–101.

Ryan, R. M., Stiller, J. D., & Lynch, J. H. (1994). Representations of relationships to teachers, parents, and friends as predictors of academic motivation and self-esteem. Journal of Early Adolescence, 14(2), 226–249. https://doi.org/10.1177/027243169401400207.

Satterthwaite, F. E. (1941). Synthesis of variance. Psychometrika, 6(5), 309–316.

Schoeler, T., Duncan, L., Cecil, C. M., Ploubidis, G. B., & Pingault, J. B. (2018). Quasi-experimental evidence on short- and long-term consequences of bullying victimization: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 144(12), 1229–1246. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000171.

Serdiouk, M., Rodkin, P., Madill, R., Logis, H., & Gest, S. (2015). Rejection and victimization among elementary school children: The buffering role of classroom-level predictors. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 43(1), 5–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-013-9826-9.

Shell, M. D., Gazelle, H., & Faldowski, R. A. (2014). Anxious solitude and the middle school transition: A diathesis × stress model of peer exclusion and victimization trajectories. Developmental Psychology, 50(5), 1569–1583.

Smeraglia, K. F. (2017). The mediating role of social preference in the relationship between teacher–student relationship quality and peer victimization. Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/4901. Accessed 6 May 2020.

Söderberg, P., & Björkqvist, K. (2020). Victimization from peer aggression and/or bullying: Prevalence, overlap, and psychosocial characteristics. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 29(2), 131–147. https://doi.org/10.1080/10926771.2019.1570410.

Veenstra, R., Lindenberg, S., Munniksma, A., & Dijkstra, J. K. (2010). The complex relation between bullying, victimization, acceptance, and rejection: Giving special attention to status, affection, and sex differences. Child Development, 81(2), 480–486.

Walker, J. M. T., & Hoover-Dempsey, K. V. (2015). Parental engagement and classroom management. In E. T. Emmer & E. J. Sabornie (Eds.), Handbook of classroom management (2nd ed., pp. 459–478). New York: Routledge.

Wei, H. S., Williams, J. H., Chen, J. K., & Chang, H. Y. (2010). The effects of individual characteristics, teacher practice, and school organizational factors on students’ bullying: A multilevel analysis of public middle schools in Taiwan. Children and Youth Services Review, 32(1), 137–143.

Wentzel, K. R. (2003). Sociometric status and adjustment in middle school: A longitudinal study. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 23(1), 5–28.

Zhang, D. (2017). A coefficient of determination for generalized linear models. The American Statistician, 71(4), 310–316. https://doi.org/10.1080/00031305.2016.1256839.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Torino within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Claudio Longobardi

Current themes of research

Teacher–student relationship; bullying and victimization, peer nominations, social media

Most relevant publications

Longobardi, C., Gullotta, G., Ferrigno, S., Jungert, T., Thornberg, R., & Settanni, M. (2020). Cyberbullying and cybervictimization among preadolescents: Does time perspective matter?. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12378.

Yu, C., Xie, Q., Lin, S., Liang, Y., Wang, G., Nie, Y., ... & Longobardi, C. (2020). Cyberbullying Victimization and Non-suicidal Self-Injurious Behavior Among Chinese Adolescents: School Engagement as a Mediator and Sensation Seeking as a Moderator. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 572521. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.572521.

Longobardi, C., Gastaldi, F. G. M., Prino, L. E., Pasta, T., & Settanni, M. (2016). Examining student-teacher relationship from students’ point of view: Italian adaptation and validation of the young children’s appraisal of teacher support questionnaire. The Open Psychology Journal. https://doi.org/10.2174/1874350101609010176.

Serena Ferrigno

Current themes of research

Teacher–student relationship; bullying and victimization, peer nominations

Most relevant publications

Longobardi, C., Gullotta, G., Ferrigno, S., Jungert, T., Thornberg, R., & Settanni, M. (2020). Cyberbullying and cybervictimization among preadolescents: Does time perspective matter?. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1111/sjop.12686.

Giulia Gullotta

Current themes of research

Teacher–student relationship; bullying and victimization, peer nominations

Most relevant publications

Longobardi, C., Pasta, T., Marengo, D., Prino, L. E., & Settanni, M. (2020). Measuring quality of classroom interactions in italian primary school: Structural validity of the CLASS K–3. The Journal of Experimental Education, 88(1), 103–122. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220973.2018.1533795.

Tomas Jungert

Current themes of research

Teacher–student relationship; bullying and victimization, peer nominations

Most relevant publications

Jungert, T., Holm, K., Iotti, N. O., & Longobardi, C. (2020). Profiles of bystanders’ motivation to defend school bully victims from a self-determination perspective. Aggressive Behavior. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.21929.

Iotti, N. O., Thornberg, R., Longobardi, C., & Jungert, T. (2020). Early adolescents’ emotional and behavioral difficulties, student–teacher relationships, and motivation to defend in bullying incidents. Child & Youth Care Forum, 1(49), 59–75. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-019-09519-3.

Longobardi, C., Gullotta, G., Ferrigno, S., Jungert, T., Thornberg, R., & Settanni, M. (2020). Cyberbullying and cybervictimization among preadolescents: Does time perspective matter?. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1111/sjop.12686.

Robert Thornberg

Current themes of research

Teacher–student relationship; bullying and victimization, peer nominations

Most relevant publications

Eriksson, E., Boistrup, L. B., & Thornberg, R. (2020). “You must learn something during a lesson”: how primary students construct meaning from teacher feedback. Educational Studies, 1-18.

Longobardi, C., Borello, L., Thornberg, R., & Settanni, M. (2020). Empathy and defending behaviours in school bullying: The mediating role of motivation to defend victims. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 90(2), 473-486. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12289.

Marengo, D., Jungert, T., Iotti, N. O., Settanni, M., Thornberg, R., & Longobardi, C. (2018). Conflictual student–teacher relationship, emotional and behavioral problems, prosocial behavior, and their associations with bullies, victims, and bullies/victims. Educational Psychology, 38(9), 1201–1217. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2018.1481199.

Davide Marengo

Current themes of research

Statistics, social media, teacher–student relationship; bullying and victimization, peer nominations

Most relevant publications

Marengo, D., Jungert, T., Iotti, N. O., Settanni,M., Thornberg, R., & Longobardi, C. (2018). Conflictual student– teacher relationship, emotional and behavioral problems, prosocial behavior, and their associations with bullies, victims, and bullies/victims. Educational Psychology, 38(9), 1201–1217. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2018.1481199

Longobardi, C., Settanni, M., Prino, L. E., Fabris, M. A., & Marengo, D. (2019). Students’ psychological adjustment in normative school transitions from kindergarten to high school: Investigating the role of teacher-student relationship quality. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1238. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01238.

Marengo, D., Settanni, M., Prino, L. E., Parada, R. H., & Longobardi, C. (2019). Exploring the dimensional structure of bullying victimization among primary and lower-secondary school students: Is one factor enough, or do we need more? Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 770. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00770.

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Longobardi, C., Ferrigno, S., Gullotta, G. et al. The links between students’ relationships with teachers, likeability among peers, and bullying victimization: the intervening role of teacher responsiveness. Eur J Psychol Educ 37, 489–506 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-021-00535-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-021-00535-3