Abstract

When responding to knowledge questions, people monitor their confidence in the knowledge they retrieve from memory and strategically regulate their responses so as to provide answers that are both correct and informative. The current study investigated the association between subjective confidence and the use of two response strategies: seeking help and withholding answers by responding “I don’t know”. Seeking help has been extensively studied as a resource management strategy in self-regulated learning, but has been largely neglected in metacognition research. In contrast, withholding answers has received less attention in educational studies than in metacognition research. Across three experiments, we compared the relationship between subjective confidence and strategy use in conditions where participants could choose between submitting answers and seeking help, between submitting and withholding answers, or between submitting answers, seeking help, and withholding answers. Results consistently showed that the association between confidence and help seeking was weaker than that between confidence and withholding answers. This difference was found for participants from two different populations, remained when participants received monetary incentives for accurate answers, and replicated across two forms of help. Our findings suggest that seeking help is guided by a wider variety of considerations than withholding answers, with some considerations going beyond improving the immediate accuracy of one’s answers. We discuss implications for research on metacognition and regarding question answering in educational and other contexts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In everyday life, people answer knowledge questions in various situations such as examinations, professional meetings, police interrogations, and informal conversations. Imagine, for instance, that a friend asks you: “In what year was the first Nobel Prize awarded?” You will most probably strive to provide a correct answer that is also informative (maxims of quality and quantity, Grice, 1975). To accomplish this, you will strategically regulate the answer you give depending on your knowledge and the needs of the asking person (for reviews, see Graesser & Murachver, 1985; Singer, 1985). Similarly, in educational settings, students use answer strategies when responding to questions in tests and examinations (e.g., AlMahmoud et al., 2019; Nickerson et al., 2015).

In the present study, we consider question answering from a metacognitive perspective. This perspective emphasizes the importance of people’s assessments of their own cognitions (metacognitive monitoring) for self-regulation and behavior (metacognitive control; e.g., Dunlosky & Metcalfe, 2009; Fiedler et al., 2019; Koriat, 2007). In the case of answering knowledge questions, metacognitive monitoring corresponds to people’s confidence in the accuracy of the knowledge they retrieve from memory, and metacognitive control corresponds to how and how long people search their memories as well as to people’s strategic regulation of the answers they provide (for a review, see Goldsmith, 2016).

Metacognition research has identified two strategies people use to achieve high accuracy in the absence of exact knowledge: withholding answers (Hanczakowski et al., 2013; Higham, 2007; Koriat & Goldsmith, 1994, 1996) and providing coarse-grained answers (e.g., Goldsmith et al., 2005; Luna et al., 2011; Sauer & Hope, 2016; Weber & Brewer, 2008; Yaniv & Foster, 1997; for a combination of the two strategies, see Ackerman & Goldsmith, 2008). That is, you might avoid giving a wrong answer by not providing any information (e.g., by responding “I don’t know”) or by adjusting the preciseness (or coarseness) of the information you provide until your answer is likely to be correct (e.g., “in the early twentieth century” rather than “in 1901”). Unfortunately, withholding answers and providing coarse-grained answers conflict with the goal of informativeness. That is, responding too often with “I don’t know” and providing ridiculously coarse answers (e.g., “after the Middle Ages”) both violate social and pragmatic norms of communication according to which one should provide reasonably informative answers (Grice, 1975; see Goldsmith, 2016, for a review). In the present study, we therefore address another strategy that allows increasing the correctness of answers while, at the same time, maintaining high informativeness: seeking help. For instance, searching the Internet or consulting someone with expertise in the history of science may enable you to give a correct and precise answer to the question about the Nobel Prize.

As detailed in the following sections, help seeking has been extensively studied in educational and psychological research on self-regulated learning. At the same time, it has been largely neglected in metacognition research. In contrast, withholding answers has received much less attention in studies on self-regulated learning than in metacognition research. The present study therefore examines both help seeking and withholding answers in a question-answering task that is relevant to many real-life situations.

Help seeking

For more than three decades, help seeking has been acknowledged as an important resource management strategy in self-regulated learning (e.g., Butler, 2013; Coughlin et al., 2015; Karabenick & Berger, 2013; Karabenick & Gonida, 2018; Nelson-Le Gall & Resnick, 1998). A large body of research shows that seeking help is one of the tools actively engaged, motivated, and successful learners use to accomplish desired goals. For instance, Zimmerman and Martinez-Pons (1990) found help seeking to be among the learning strategies preferred by more advanced students. Karabenick and Knapp (1991) reported that students who engage in a variety of learning strategies are also more likely to seek help. Nevertheless, help seeking is unique among learning strategies in that some but not all types of help seeking promote learning and understanding (e.g., Aleven et al., 2003; Karabenick, 2011; Karabenick & Berger, 2013; Nelson-Le Gall, 1981; Newman, 1994). Instrumental help seeking, such as asking for hints after trying to solve a problem alone, is considered as adaptive (Nelson-Le Gall, 1981). In contrast, executive help seeking, such as asking for answers instead of trying to solve a problem alone, is work avoidant and maladaptive (Nelson-Le Gall, 1981). Also, unlike most other learning strategies, help seeking often involves social interactions, either face-to-face or technology-mediated (Karabenick & Berger, 2013; Karabenick & Gonida, 2018; Newman, 1998, 2000; Volet & Karabenick, 2006). Finally, help seeking is typically associated with psychological costs, such as threat to self-esteem through the admission of inadequacy, feelings of embarrassment, or even stigmatization (Halabi & Nadler, 2017; Nadler, 1991, 2017).

Over the years, several models of the help seeking process have been proposed (e.g., Nelson-Le Gall, 1981, 1985; Newman, 1994). Typically, these models include the following steps: (1) recognizing that a problem exists, (2) determining that help is needed or wanted, (3) deciding whether to seek help, (4) selecting what type of help to seek, (5) deciding whom to ask for help or which helping source to access, (6) soliciting help, (7) obtaining help, and (8) processing the help received (Karabenick & Berger, 2013; Karabenick & Gonida, 2018; Makara & Karabenick, 2013). Specific instances of help seeking may differ in the order of steps and include only a subset of steps.

In the present study, we focus on metacognitive aspects of the first three steps in the help seeking process, thereby addressing the micro-level of self-regulated learning (cf. Greene & Azevedo, 2009; Karabenick & Gonida, 2018; Volet & Karabenick, 2006). Recognizing that a problem exists and determining that one needs help both involve metacognitive monitoring. This monitoring then forms the basis for seeking help, which is a metacognitive control process (cf. Ackerman & Thompson, 2017). Although it is generally acknowledged that metacognitive skills are critical for recognizing one’s need for help (e.g., Karabenick & Berger, 2013; Karabenick & Gonida, 2018; Nelson-Le Gall, 1985; Newman, 1994; van der Meij, 1990), much remains to be learned about the association between metacognitive monitoring processes and help seeking.

Most prior research on recognizing one’s need for help focused on the relationship between global measures of perceived need and actual help seeking or, alternatively, intentions to seek help. These studies revealed mixed findings. For instance, Karabenick and Knapp (1988) asked students whether they needed help in one or more of the courses they were taking during the term or with their study skills in general. Relating these global measures of need to actual help seeking showed that students who reported moderate levels of need sought the most help, whereas students who reported high levels of need sought only little more help than students who reported low levels of need. Karabenick and Knapp (1991) used a very similar method, but found that help seeking increased with perceived need for help. In a study by Newman and Goldin (1990), greater perceived need for help was associated with increased reluctance to seek help in 12-year-olds but unrelated to reluctance to seek help in younger children (8- and 10-year-olds). Presumably, various individual differences, situational variables, and cultural factors contribute to the differences between these findings (e.g., Butler, 2013; Nadler, 2017; Newman, 2000; Volet & Karabenick, 2006). While these influences on help seeking have important theoretical and practical implications, they might cloud the relationship between perceived need for help and help seeking. Consequently, investigating help seeking in carefully controlled experiments that examine people’s need for help at the level of individual questions has the potential to extend our understanding of the metacognitive monitoring processes that underlie help seeking.

Only a few prior studies have experimentally evaluated the relationship between people’s need for help and help seeking. These studies operationally defined need for help as low subjective confidence in one’s own answers or solutions. An experiment with preschoolers (Coughlin et al. 2015), three experiments with children from Grades 1 to 5 (Nelson-Le Gall & Jones, 1990; Nelson-Le Gall et al., 1990; Nelson & Fyfe, 2019), and an experiment with female college students (Cotler et al., 1970), all showed that participants sought help more often when they had low confidence in their answers. Together, these studies suggest that help seeking is related to subjective confidence in a straightforward fashion.

At the same time, several questions remain. Most importantly, no study has compared the relationship between subjective confidence and help seeking to the relationship between subjective confidence and the use of other metacognitive control strategies. Moreover, previous studies used confidence scales with few levels that denied participants the opportunity to differentiate finely graded levels of confidence. The present study aims to fill these gaps.

Withholding answers

Basic and applied research on metacognition has extensively investigated withholding answers as a metacognitive control process. In particular, studies addressed when and why people respond “I don’t know” or cross out their answers rather than provide their best-candidate answer. These studies typically assessed control sensitivity (e.g., Koriat & Ackerman, 2010; Koriat & Goldsmith, 1996; for a review, see Goldsmith, 2016). Control sensitivity reflects the extent to which people base metacognitive control processes such as withholding answers on subjective confidence. It was usually measured as the within-subject correlation between confidence and withholding answers. Most studies found close to perfect control sensitivity (i.e., -1) in adults and even young children, indicating that subjective confidence plays a dominant role in withholding answers (e.g., Koriat & Ackerman, 2010; Koriat & Goldsmith, 1996; for a review, see Goldsmith, 2016).

Theoretical accounts proposed that high control sensitivity is due to people submitting an answer when their confidence in its correctness passes a criterion level of confidence and withholding it otherwise (Ackerman & Goldsmith, 2008; Koriat & Goldsmith, 1996). The location of the confidence criterion was found to be dependent on people’s motivation to provide accurate answers. In particular, people adjust their withholding of answers in response to the relative payoffs and penalties associated with providing correct and wrong answers (e.g., Higham, 2007; Koriat & Goldsmith, 1996; Koriat et al., 2001). For instance, Higham (2007, Experiment 1) found that participants who lost 4 points per wrong answer withheld more answers than participants who lost 0.25 points per wrong answer. Notably, this experimental manipulation created a situation in which withholding answers is associated with both benefits and costs, as is often the case with help seeking (e.g., Halabi & Nadler, 2017; Nadler, 1991, 2017).

There is robust evidence that the option to withhold answers improves the accuracy of submitted answers (see Goldsmith, 2016, for a review). That is, this option increases what Koriat and Goldsmith (1994, 1996) termed output-bound accuracy. Output-bound accuracy pertains to the proportion of correct answers among the answers people choose to submit. In contrast, input-bound accuracy corresponds to the proportion of correct answers among the answers to the entire set of questions. High output-bound accuracy is essential in eyewitness testimony where witnesses choose what information to provide (Koriat & Goldsmith, 1996; Shapira & Pansky, 2019; Weber & Perfect, 2012). It is also crucial for the various educational settings where students answer questions. So far, however, educational research has narrowly focused on how withholding answers affects scores in multiple-choice examinations and aptitude tests. Some studies found that instructions to withhold answers in combination with scoring methods that penalize guessing improve test reliability or validity (e.g., McHarg et al., 2005; Muijtjens et al., 1999). At the same time, however, it has been demonstrated that this approach may disadvantage test takers with personality characteristics such as risk-awareness or those with poor metacognitive skills (for reviews, see Higham & Arnold, 2007; Nickerson et al., 2015).

The present study

In the present study, we aimed to elucidate the metacognitive processes involved in help seeking and withholding answers in a question-answering task. We tested two predictions. Based on the literature reviewed in the Introduction, our first prediction was that subjective confidence in the correctness of one’s answers would guide people’s strategic choices, with confidence being inversely related to both seeking help and withholding answers.

The second prediction was that associations with confidence would be weaker for help seeking than for withholding answers. This prediction was based on the expectation that considerations beyond improving the immediate accuracy of one’s answers would impact help seeking more than withholding answers. As noted earlier, strong associations between confidence and withholding answers suggest that improving the immediate accuracy of one’s answers is the main reason for withholding answers (e.g., Koriat & Ackerman, 2010; Koriat & Goldsmith, 1996; for a review, see Goldsmith, 2016). In contrast, people might seek instrumental help not only to improve the immediate accuracy of answers, but also in order to improve the informativeness of answers, satisfy curiosity (Berlyne & Frommer, 1966; Ferguson et al., 2015; Son & Metcalfe, 2000), or receive feedback about the accuracy of their knowledge (Bamberger, 2009; Nelson-Le Gall & Jones, 1990). At the same time, people may be hesitant to seek help for various reasons, including an orientation toward independence and self-reliance (Butler, 1998; Nadler, 2017; Ryan et al., 2009), experiencing help seeking as a threat to self-esteem (Butler, 2006; Halabi & Nadler, 2017; Karabenick & Berger, 2013; Nadler, 1991, 2017), and reluctance to spend more time on task (Arbreton, 1998; Metcalfe, 2009; Santos et al., 2020; Newman & Goldin, 1990; Undorf & Ackerman, 2017). Consistent with the idea that improving immediate accuracy is not the sole impetus for help seeking, Nelson-Le Gall et al. (1990) found stronger relationships between confidence and help seeking in children when using a contingency reward system that encouraged limiting help seeking to cases in which participants thought that they needed help to answer correctly. Consequently, we expected that the association between confidence and help seeking would be weaker than that between confidence and withholding answers.

For completeness, we also examined how help seeking and withholding answers were related to the accuracy of initial answers and to the accuracy of submitted answers (output-bound accuracy; Koriat & Goldsmith, 1994, 1996). Though not the focus of this study, these findings might be relevant for future research on the metacognitive processes involved in help seeking and withholding answers. Because confidence is often positively related to the accuracy of answers (see, e.g., Ackerman et al., 2020a, b; Koriat, 2018; Koriat & Goldsmith, 1996), we expected to find that the accuracy of initial answers was inversely related to using either strategy. Also, we expected to replicate prior studies demonstrating that the option to withhold answers improved output-bound accuracy (see Goldsmith, 2016, for a review). However, it was an open question whether and to what extent the option to seek help would improve output-bound accuracy.

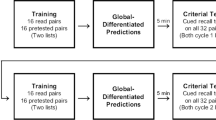

Experiment 1 represents a first step in evaluating our predictions. We used a between-participants design to compare the relationship between confidence and help seeking to that between confidence and withholding answers. In the help-seeking condition, participants had the option to seek help. In the don’t-know condition, participants had the option to withhold answers.

All participants responded to general knowledge questions that required numeric answers (e.g., “In what year was the first Nobel Prize awarded?”), as was done in previous metacognitive studies on withholding answers (e.g., Ackerman & Goldsmith, 2008; Koriat & Goldsmith, 1996). Immediately after typing each answer, participants rated their confidence in its correctness on a 0 to 100% scale. In the help-seeking condition, participants could then submit their answer or request help, that is, provide their final answer only after receiving hints in a later phase of the experiment. In the don’t-know condition, participants could submit their answer or withhold it.

In the help-seeking condition, help was provided in a separate phase at the end of the experiment, in the form of a multiple-choice version of the question with four response options (e.g., “How many countries surround the Black Sea?” – “15–20”, “21–26”, “9–14”, “3–8”). Recognizing the correct response among a small set of response options is easier than recalling it in response to the question alone (e.g., Ackerman et al., 2020a, b; Ackerman & Zalmanov, 2012; Leonesio & Nelson, 1990). Reasons for this include constraints on the number of potential answers and increases in the chance for guessing the correct response (at least 25%; higher when knowledge allows eliminating one or more response options). Thus, participants received instrumental, adaptive help (Nelson-Le Gall, 1981, 1985; Newman, 1994, 1998; for a review, see Karabenick & Gonida, 2018).

As in prior studies on seeking help and withholding answers (e.g., Higham, 2007; Koriat & Goldsmith, 1996; Nelson-Le Gall et al., 1990), we introduced a contingency reward system. Participants gained 2 points for each correct final answer and lost 2 points for each incorrect final answer. Each help request cost 1 point and people neither gained nor lost any points when responding I don’t know (cf. Koriat & Goldsmith, 1996). As mentioned in the Introduction, help seeking is usually associated with costs in real-life situations. In the present experiment, computer-mediated distribution of help and limited interactions between participants and experimenter might reduce these naturally occurring costs of help seeking (Karabenick & Knapp, 1988; Makara & Karabenick, 2013; Tricot & Boubée, 2013). Imposing a cost for help requests was therefore essential to enhance ecological validity. Also, the cost for help requests encouraged strategic behavior in that it prevented participants from maximizing their score by seeking help for each and every question (cf. Nelson-Le Gall et al., 1990).

In Experiment 2, we aimed to provide a more comprehensive picture by comparing the relationship between confidence and strategy use across four conditions: The help-seeking and don’t-know conditions used in Experiment 1 as well as a combination condition and a no-choice condition. In the combination condition, participants had both strategic options available. This condition mirrors real-life situations where people may freely choose among volunteering an answer, seeking help, and responding that they don’t know. In the no-choice condition, participants had to submit all their answers, without the option to seek help or to withhold answers. As in Experiment 1, we predicted that help seeking would be related to confidence, but less strongly than withholding answers. We expected this pattern to occur not only when comparing strategy use across the help-seeking and don’t-know conditions, but also when comparing requests for help and don’t-know responses within participants in the combination condition. This prediction is not trivial because the additional option to respond don’t know may affect help-seeking behavior through emphasizing that withholding responses may allow one to avoid the costs of help seeking. This design also allowed us to examine how the options to seek help and to withhold answers are related to output-bound accuracy, that is, the accuracy of submitted answers.

To improve the generalizability of our results, we conducted Experiment 2a in the laboratory with undergraduates and Experiment 2b via the Internet with participants from an online subject pool. Moreover, we replaced the set of Hebrew questions from Experiment 1 with a new set of English questions so that materials were in a non-native language for participants in Experiment 2a but in everyday language for participants in Experiment 2b.

In Experiment 2b, where people participated in exchange for a monetary compensation via the Internet, each point corresponded to 1 penny. This change allowed us to examine whether the association between confidence and help seeking would remain weaker than that between confidence and withholding answers despite the monetary incentive to provide accurate answers. A performance-contingent monetary bonus was also important to prevent that online participants focused only on minimizing the time they spent on the study (but see Peer et al. 2017).

In Experiment 3, we tested whether the findings obtained in Experiment 1 and Experiment 2 would generalize to another form of help. It seemed possible that providing help in the form of a multiple-choice question discouraged help seeking when participants had extremely low confidence in their knowledge. In these cases, participants may have avoided seeking help because they suspected being unable to identify the correct answer among the wrong alternatives and preferred to avoid failing after receiving help. If so, the specific type of help that we offered in Experiment 1 and Experiment 2 could potentially weaken the relationship between confidence and help seeking. We therefore provided a different type of help in Experiment 3: Participants saw the alleged response of a previous participant about whom they learned that his or her accuracy was higher than that of 80% of previous participants. This type of help dramatically increased participants’ chances to respond correctly even when they had extremely low confidence in their knowledge. Thus, in Experiment 3, participants had the opportunity to seek help from a competent peer, which is among the types of help people value most (for a review, see Makara & Karabenick, 2013).

In summary, in the present study, we aimed to elucidate the metacognitive processes involved in help seeking and withholding answers by testing the predictions (1) that confidence is inversely related to seeking help and withholding answers and (2) that associations with confidence are weaker for help seeking than for withholding answers. We evaluated these predictions in two different populations, with two different sets of knowledge questions, using both point incentives and monetary incentives, and when providing two different forms of help.

Experiment 1

Experiment 1 included two between-participants conditions: a help-seeking condition and a don’t-know condition, in which participants had the option to seek help or to withhold answers, respectively. We predicted (1) that people would seek help when their confidence in the accuracy of initial answers was low and (2) that the relationship between confidence and strategy use would be weaker in the help-seeking condition than in the don’t-know condition.

Method

Participants

In this and all subsequent experiments, we set a sample size of at least 25 participants per group, based on previous research that examined related issues with similar materials (e.g., Ackerman & Goldsmith, 2008; Koriat & Goldsmith, 1996). Participants were 54 Technion undergraduates, randomly assigned to the help-seeking and don’t-know conditions (n = 27 in each group). Planned exclusion criteria were answer accuracy < 2 SD below the mean and providing the same confidence rating for all answers. No participants were excluded from data analysis after applying these criteria.

Materials

Materials were 38 general-knowledge questions (in Hebrew) that covered a broad range of topics and required quantitative-numeric responses (e.g., “In what year did Edison produce the first electric light bulb?”, “What is the percentage of oxygen in the air?”, “How many letters are in the Greek alphabet?”). Each question was presented with a required answer interval that was reasonably informative (e.g., “Please respond with a 20-year interval”). Questions and answer intervals were chosen from a pool developed by Sidi et al. (2018). To ensure that there was variability in the accuracy of answers and confidence judgments, we chose questions with pretested accuracy rates between 20 and 80%. In the help phase, participants were presented with four plausible intervals of the same size, one of which encompassed the correct answer (e.g., “How many bones are there in a human hand?” – “7–17”, “29–39”, “40–50”, “18–28”). Two specific questions served as practice items and were not included in the analysis (“In what year was the social media platform Facebook launched?”, “In what year was the movie The Godfather released?”).

Procedure

All participants were tested in the laboratory in small groups and could leave only after 30 min. Participants answered each question by providing a bounded range of values at a required interval (e.g., 5-year interval). The required interval was presented along with the question. Immediately afterwards and on the same screen, participants rated their confidence in the correctness of their answer on a 0 to 100% scale (“What is the chance that your answer encompasses the correct value?”). Participants were required to select a confidence judgment other than 50%, which was the initial position of the pointer on the scale.

After each confidence rating, participants in the help-seeking condition could either click a Submit button to move on to the next question or seek help by clicking a Get help button. Instructions explained that when participants sought help with a question, this question would be presented in a subsequent help phase with four alternative intervals, one of which encompassed the correct value. In the don’t-know condition, participants could withhold their answers by clicking an I don’t know button instead of the Submit button. Instructions for both groups explained that each submitted answer would be scored with 2 points when correct and penalized with -2 points when incorrect. Participants in the help-seeking condition were told that for each help request, 1 point would be deduced from their score and that answers in the help phase would be scored with 2 points when correct and penalized with -2 points when incorrect. Participants in the don’t-know condition learnt that they would neither gain nor lose any points for don’t-know responses. A legend detailing the point values relevant for the respective condition was depicted on all screens. Participants were instructed to gain as many points as possible, but no monetary incentives were offered.

Following the last question, participants in the help-seeking condition completed the help phase. In this phase, they were presented with the questions they had requested help for, in the same order as before. They answered each question by selecting one of the four provided intervals and rated their confidence in the correctness of the selected interval.

Measures and data analysis

Confidence judgments were obtained on a percentage scale. Initial answers were scored as correct (100) or wrong (0). We calculated the percentage of questions for which participants sought help or withheld answers. To test for equivalence across groups, confidence, accuracy of answers, and frequency of strategy use were submitted to t tests.

If people seek help and withhold answers when their confidence in the accuracy of their answers is low, they should be less confident in answers to questions for which they use the available strategy than in answers to questions for which they do not use the available strategy. We evaluated this prediction in a mixed ANOVA on confidence with available strategy (help seeking, don’t know) as a between-subjects factor and strategy use (no, yes) as a within-subjects factor. In this analysis, we expected a main effect of strategy use.

To better understand the relationship between confidence judgments and strategy use, we examined the range of confidence judgments associated with submitting answers and using the available strategy. If the association between confidence and help seeking is weaker than that between confidence and withholding answers, the overlap in confidence ranges should be larger in the help-seeking than in the don’t-know condition. We tested this prediction using t tests.

Moreover, a weaker relationship between confidence and strategy in the help-seeking than in the don’t-know condition should reduce control sensitivity (Koriat & Goldsmith, 1996). We indexed control sensitivity by within-participant gamma correlations between confidence and strategy use (yes/no) and compared it across groups using t tests.

Though not the focus of this study, we also examined the relationship between strategy use and the accuracy of initial answers using a 2 (available strategy group: help seeking, don’t know) by 2 (strategy use: no, yes) mixed ANOVA.

Results

Table 1 reports descriptive statistics. Conditions did not differ in confidence or accuracy of answers, ts < 1.06. Frequencies of strategy use were similar across conditions, t(52) = 1.15, p = 0.257, d = 0.31.

Table 2 shows descriptive statistics conditionalized on strategy use. A 2 (available strategy group: help seeking, don’t know) by 2 (strategy use: no, yes) mixed ANOVA on confidence revealed a significant main effect of strategy use, F(1, 50) = 156.67, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.76, indicating that participants used either strategy when their confidence was low. No other effects were significant, available strategy group: F(1, 50) = 1.65, p = 0.205, ηp2 = 0.03, interaction: F(1, 50) = 1.76, p = 0.190, ηp2 = 0.03.

The range of confidence judgments associated with submitting answers and using the available strategy in the help-seeking and don’t-know conditions is presented in Fig. 1. In both conditions, minimum confidence in submitted answers was lower than maximum confidence in answers to questions for which people used a strategy. The resulting overlap in confidence range was larger in the help-seeking than in the don’t-know condition, t(50) = 3.40, p = 0.001, d = 0.94. This difference was due to higher maximum confidence associated with strategy use in the help-seeking than in the don’t-know condition, t(50) = 2.55, p = 0.014, d = 0.71. In contrast, minimum confidence associated with using the available strategy and minimum and maximum confidence in submitted answers were similar across conditions, all t < = 1.08, p > = 0.287. These differences were accompanied by a marginally significant and medium-sized difference in control sensitivity across conditions, t(48) = 1.95, p = 0.057, d = 0.55 (see Table 2 for descriptive statistics).

A 2 (available strategy group: help seeking, don’t know) by 2 (strategy use: no, yes) mixed ANOVA on the accuracy of initial answers revealed a main effect of available strategy group, F(1, 50) = 6.45, p = 0.014, ηp2 = 0.11, indicating higher accuracy of answers in the help-seeking condition than in the don’t-know condition. A significant main effect of strategy use, F(1, 50) = 27.88, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.36, indicated that strategy use was accompanied by lower accuracy than submitting answers. The interaction was not significant, F(1, 50) = 1.64, p = 0.206, ηp2 = 0.03. The main effect of available strategy group was unexpected. Because it did not replicate across Experiment 2 and Experiment 3, it is likely to be due to some incidental factor rather than yield theoretical insight. We therefore do not discuss this effect further.

Discussion

Experiment 1 revealed that participants sought help and responded don’t know when answering knowledge questions from memory. Results showed that subjective confidence was negatively associated with both help seeking and withholding answers: Participants used either strategy when their confidence in the correctness of answers was low. More importantly, there were indications that confidence was less strongly related to help seeking than to withholding answers.

Experiment 2

In Experiment 2, we further examined help seeking and withholding answers as metacognitive control processes by comparing the relationship between confidence and strategy use across four conditions: The help-seeking and don’t-know conditions used in Experiment 1, a combination condition where participants had both strategic options available, and a no-choice condition where participants could neither seek help nor withhold answers.

Experiment 2a

Experiment 2a was a laboratory study and participants came from the same undergraduate population as in Experiment 1. We used a new set of English general-knowledge questions. Hence, materials were in a non-native language for participants. This was done to generalize findings across questions and to ensure consistency with the following experiments where participants came from predominantly English-speaking countries. We again predicted that help seeking would be related to confidence, but less strongly than withholding answers. We expected this pattern to occur not only when comparing strategy use across the help-seeking and don’t-know conditions as in Experiment 1, but also in the new combination condition where we compared requests for help and don’t-know responses within participants.

Method

Participants

Participants were 100 Technion undergraduates, randomly assigned to the help-seeking, don’t-know, combination, and no-choice conditions. The data of three participants were excluded after applying the same exclusion criteria used in Experiment 1 and two additional constraints used in preparation of the online version (Experiment 2b): at least 50% performance on vigilance items (see Materials) and at least 20 items left after item screening (see Results). This left 25 participants in the help-seeking and combination conditions, 23 participants in the don’t-know condition, and 24 participants in the no-choice condition.

Materials

Materials were a new set of 38 English general-knowledge questions that required quantitative-numeric responses in predefined answer intervals and covered a broad range of topics (e.g., “How many keys does the standard piano have?”, “In what year did the French Revolution start?”, “How many centimeters are in a foot?”). One specific question served as a practice item (“In what year did Barack Obama’s US presidency begin?”) and four very easy questions served as vigilance items (e.g., “How many arms does an octopus have? “). Practice and vigilance items were not included in the analyses. The remaining questions were pretested (N = 20) to have accuracy rates between 20 and 80%, as was the case in Experiment 1.

Procedure

The procedure was similar to that used in Experiment 1, with the following modifications. There were two new conditions. In the combination condition, participants could submit answers by clicking a Submit button, seek help by clicking a Get help button, or withhold answers by clicking an I don’t know button. In the no-choice condition, participants had to submit all answers.

Additional modifications were made in order to allow running a very similar experiment online (see Experiment 2b). Four very easy vigilance questions were randomly interspersed among the questions so that we could test participant engagement. Confidence judgments were collected on a separate screen that appeared immediately after participants submitted their answer. Participants had the option to indicate their confidence or, alternatively, click a Sorry, I do not remember my answer button. Finally, in the help phase, participants were presented with five random questions rather than with the questions they requested help for.

Measures and data analysis

We obtained the same measures as in Experiment 1. Analyses were identical to Experiment 1 and complemented by analyses that evaluated our predictions in the combination condition.

If people in the combination condition seek help and withhold answers when they have low confidence in the accuracy of their answers, they should be less confident in answers for which they used either strategy than in answers they submitted (i.e., answers for which they did not use a strategy). We evaluated this prediction in a one-way ANOVA on confidence with strategy use (no strategy use, seeking help, responding don’t know) as a within-subjects factor, followed by t tests for paired samples. We expected higher confidence when participants submitted their answers, that is, when they did not use a strategy.

If, in the combination condition, the association between confidence and help seeking is weaker than the association between confidence and withholding answers, then the overlap in confidence between questions for which participants submitted answers or sought help should be larger than the overlap in confidence between questions for which participants submitted answers or withheld answers. Also, control sensitivity should be weaker for help requests than for don’t-know responses. We tested these predictions using paired-samples t tests.

The accuracy of initial answers in the combination condition was investigated using a one-way ANOVA with strategy use (no strategy use, seeking help, responding don’t know) as a within-subjects factor and follow-up t tests for paired samples.

Finally, we tested whether the availability of a strategy increased output-bound accuracy, that is, the accuracy of submitted answers using a one-way ANOVA with condition (help seeking, don’t know, combination, and no choice) as a between-subjects factor and follow-up t tests.

Results

In the analyses, we eliminated twelve answers (0.37%) that participants reported not to remember when asked to make a confidence judgment and 10 answers with exceptionally long response times (> 90 s; 0.31%).

Table 1 reports descriptive statistics. Conditions did not differ in confidence or accuracy, Fs < 1. Participants used the available strategy less often in the help-seeking than in the don’t-know condition, t(46) = 5.75, p < 0.001, d = 1.66, and, in the combination condition, participants less often sought help than they responded don’t know, t(24) = 3.30, p = 0.003, d = 0.67. Frequencies of help seeking were equivalent across the help-seeking and combination condition, but frequencies of don’t-know responses were higher in the don’t-know than in the combination condition (see Table 1).

Table 2 shows descriptive statistics conditionalized on strategy use. In the help-seeking and don’t-know conditions, a 2 (available strategy group: help seeking, don’t know) by 2 (strategy use: no, yes) mixed ANOVA on confidence revealed a significant main effect of strategy use, F(1, 42) = 145.98, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.78, indicating that participants used either strategy when their confidence was low. The main effect of available strategy group was not significant, F < 1. A significant interaction, F(1, 54) = 24.57, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.06, demonstrated higher confidence when participants used the available strategy in the help-seeking than in the don’t-know condition. In the combination condition, a repeated measures ANOVA revealed that confidence varied across questions for which people submitted answers, sought help, or responded don’t know, F(2, 34) = 88.90, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.84. As expected, pairwise comparisons confirmed that help seeking was associated with higher confidence than responding don’t know but with lower confidence than submitting answers (see Table 2).

The overlap in confidence between questions for which participants submitted answers or used a strategy (see Fig. 2) was larger in the help-seeking than in the don’t-know condition, t(42) = 4.76, p < 0.001, d = 1.44. This was due to higher minimum confidence when using the available strategy, t(42) = 3.06, p = 0.004, d = 0.92, and lower minimum confidence in submitted answers, t(46) = 5.66, p < 0.001, d = 1.64, in the help-seeking than in the don’t-know condition. In contrast, maximum confidence associated with strategy use and submitted answers was similar across conditions, both t < = 1.24, p > = 0.222. A very similar pattern emerged in the combination condition, where the confidence overlap with submitted answers was larger for help requests than for don’t-know responses, t(17) = 4.63, p < 0.001, d = 1.12. This difference was due to help requests being associated with higher minimum confidence, t(17) = 5.52, p < 0.001, d = 1.34, and higher maximum confidence, t(17) = 4.63, p < 0.001, d = 1.12, than don’t-know responses.

Control sensitivity (see Table 2 for descriptive statistics) was weaker in the help-seeking condition than in the don’t-know condition, t(54) = 4.80, p < 0.001, d = 1.45. In the combination condition, control sensitivity for help requests was not significantly negative and weaker than for don’t-know responses, t(17) = 6.15, p < 0.001, d = 1.49.

Concerning accuracy of the initial answers participants provided before choosing whether to submit them or use the available strategy in the help-seeking and don’t-know conditions, a mixed 2 (strategy use: no, yes) by 2 (available strategy group: help seeking, don’t know) ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of strategy use, F(1, 42) = 27.72, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.40, indicating that strategy use was accompanied by low accuracy. The main effect of available strategy group was not significant, F(1, 42) = 2.34, p = 0.134, ηp2 = 0.05. A significant interaction showed that this difference in accuracy was less pronounced in the help-seeking condition, F(1, 42) = 7.02, p = 0.011, ηp2 = 0.14. In the combination condition, accuracy of initial answers varied across submitted answers, help requests, and don’t-know responses, F(2, 34) = 11.73, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.41, and pairwise comparisons confirmed higher accuracy for submitted answers than for help requests or don’t-know responses (see Table 2).

Finally, the inclusion of the no-choice group enabled us to test whether the availability of a strategy increased output-bound accuracy. Indeed, accuracy of submitted answers (see Table 1 for the no-choice condition and Table 2 for the other conditions) varied across conditions, F(3, 93) = 5.84, p = 0.001, ηp2 = 0.16. Compared to the no-choice condition, accuracy of submitted answers was higher in the don’t-know condition, t(45) = 2.89, p = 0.006, d = 0.84, and in the combination condition, t(47) = 2.29, p = 0.026, d = 0.65, but not in the help-seeking condition, t < 1. As will be discussed below, this suggests that people seek help for reasons other than improving answer accuracy alone.

Discussion

Experiment 2a replicated the two main findings of Experiment 1. First, confidence was negatively associated with both help seeking and withholding answers. More importantly, the relationship between confidence and strategy use was weaker for help seeking than for withholding answers, as became apparent in reduced control sensitivity. A novel finding was that this pattern held when participants had both strategic options available. Concerning output-bound accuracy, the current experiment revealed that the option to seek help did not improve the accuracy of submitted answers, whereas the option to withhold answers did so.

Experiment 2b

Experiment 2b was a replication of Experiment 2a in an online study with a larger sample and with a population that was more diverse with regard to age and education. An important difference from the previous experiments was that participants received a performance-contingent monetary bonus. Administering a monetary incentive to provide accurate answers provided a strong test of the hypothesis that help seeking is guided by a variety of considerations beyond improving the immediate accuracy of one’s answers. We expected to replicate the findings from Experiment 2a.

Methods

Participants

Participants from predominantly English-speaking countries (UK, US, Ireland, New Zealand, and Australia) were recruited from the Prolific online subject pool (www.prolific.co). We recruited 203 participants who were randomly assigned to the help-seeking, don’t-know, combination, and no-choice conditions. The experiment took approximately 20 min and participants were paid 1.30£ plus a maximum bonus of 0.76£ based on their performance. We excluded the data of 22 participants (10.84%) who quit partway through the experiment. Additionally, we excluded the data of four participants after applying the same exclusion criteria as in Experiment 2a. This left 46 participants in the help-seeking, don’t-know, and combination conditions and 44 participants in the no-choice condition. Most participants (98%) reported their everyday language to be English.

Materials and procedure

Materials were the same as in Experiment 2a. The procedure was identical to Experiment 2a with the following exceptions. Participants were recruited online and received a monetary compensation and a performance-based bonus pay. Participants received exactly the same instructions as in Experiment 2a except that points were replaced with pennies (1 point = 1p). Consequently, instructions for all groups explained that each submitted answer would be scored with 2p when correct and penalized with -2p when incorrect. Participants in the help-seeking and combination condition were told that 1p would be deduced from their score for each help request, and that answers in the help phase would be scored with 2p when correct and penalized with -2p when incorrect. Participants in the don’t-know and combination conditions learnt that they would neither gain nor lose any money for don’t-know responses. A legend detailing the incentives relevant for the respective condition was depicted on all screens.

Measures and data analysis

Measures and data analysis were identical to Experiment 2a.

Results

We eliminated from the data analyses 19 answers (0.65%) that participants reported not to remember when asked to make a confidence judgment and 38 answers (0.65%) with response latencies > 90 s. Because the experiment was conducted online, we eliminated 125 answers (2.14%) for which participants switched to another computer window while asked to provide answers, make confidence judgments, or submit answers/use a strategy.

Table 1 reports descriptive statistics. Conditions did not differ in confidence or accuracy, Fs < 1. Participants used the available strategy less often in the help-seeking condition than in the don’t-know condition, t(94) = 5.04, p < 0.001, d = 1.03, and, similarly, in the combination condition, participants less often sought help than they responded don’t know, t(42) = 3.46, p = 0.001, d = 0.53. Either strategy was used more when it was the only available option than in the combination condition (see Table 1).

Table 2 shows descriptive statistics conditionalized on strategy use. In the help-seeking and don’t-know conditions, a 2 (available strategy group: help seeking, don’t know) by 2 (strategy use: no, yes) mixed ANOVA on confidence revealed a significant main effect of strategy use, F(1, 79) = 651.70, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.89, indicating that participants used either strategy when their confidence was low. A significant main effect of available strategy group, F(1, 79) = 5.02, p = 0.028, ηp2 = 0.06, revealed lower confidence in the help-seeking condition. This main effect was unexpected and did not replicate across experiments, so it is likely to be due to some incidental factor. We therefore do not discuss it further. A significant interaction, F(1, 79) = 5.20, p = 0.025, ηp2 = 0.06, demonstrated higher confidence when participants used the available strategy in the help-seeking than in the don’t-know condition. In the combination condition, a repeated measures ANOVA revealed that confidence varied across questions for which people submitted answers, sought help, or responded don’t know, F(2, 19) = 89.33, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.90, and pairwise comparisons confirmed higher accuracy for submitted answers than for help requests or don’t-know responses (see Table 2).

The overlap in confidence between questions for which participants submitted answers or used a strategy was again larger in the help-seeking than in the don’t-know condition, t(79) = 2.84, p = 0.006, d = 0.64 (see Fig. 2). This was due to lower minimum confidence in submitted answers in the help-seeking than in the don’t-know condition, t(94) = 4.69, p < 0.001, d = 0.96. In contrast, neither maximum confidence in submitted answers, nor minimum or maximum confidence when using the available strategy differed across conditions, all t < = 1.21, p > = 0.232. A very similar pattern was obtained in the combination condition, where the overlap in confidence was larger for help requests than for don’t-know responses, t(20) = 2.38, p = 0.027, d = 0.53. This difference occurred because help requests were associated with higher minimum confidence, t(20) = 2.71, p = 0.014, d = 0.61, and higher maximum confidence, t(20) = 2.38, p = 0.027, d = 0.53, than don’t-know responses.

As in Experiment 2a, control sensitivity (see Table 2 for descriptive statistics) was weaker in the help-seeking than in the don’t-know condition, t(79) = 2.68, p = 0.009, d = 0.60, and, in the combination condition, weaker for help requests than for don’t-know responses, t(20) = 3.47, p = 0.002, d = 0.80.

Concerning accuracy of the initial answers in the help-seeking and don’t-know conditions, a mixed 2 (available strategy group: help seeking, don’t know) by 2 (strategy use: no, yes) ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of strategy use, F(1, 79) = 134.33, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.63, indicating that strategy use was accompanied by low accuracy. No other effects were significant, main effect of available strategy group: F(1, 79) = 2.16, p = 0.145, ηp2 = 0.03, interaction: F < 1. In the combination condition, accuracy of initial answers varied across submitted answers, help requests, and don’t-know responses, F(2, 40) = 14.84, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.43, with pairwise comparisons confirming higher accuracy for submitted answers than for help requests or don’t-know responses (see Table 2).

The accuracy of submitted answers varied across conditions (see Table 1 for the no-choice condition and Table 2 for the other conditions), F(3, 173) = 4.89, p = 0.003, ηp2 = 0.78. Compared to the no-choice condition, accuracy of submitted answers was marginally higher in the help-seeking condition, t(85) = 1.87, p = 0.064, d = 0.40, and significantly higher in the don’t-know, t(83) = 3.84, p < 0.001, d = 0.84, and combination, t(79) = 2.68, p = 0.009, d = 0.60, conditions.

Discussion

Experiment 2b replicated the major findings of Experiment 1 and Experiment 2a with a different experimental setting, a different population, and monetary incentives. Confidence was negatively associated with help seeking and withholding answers, but the association was weaker than that between confidence and withholding answers, as became apparent in reduced control sensitivity. This finding held when only one strategic option was available and when participants could choose between the two strategic options. Finally, unlike the option to withhold answers, the option to seek help did not reliably improve output-bound accuracy, despite the monetary incentive to provide accurate answers.

Experiment 3

In Experiment 3, we tested whether results from Experiment 1 and Experiment 2 would replicate when providing a kind of help that was more helpful when participants felt ignorant: seeing responses of a competent previous participant. As mentioned above, this form of help gave participants the chance to seek an attractive form of instrumental help (for a review, see Makara and Karabenick 2013). Population and design were the same as in Experiment 2b, with the exception of the type of help offered to participants in the help-seeking and combination conditions. All predictions and analyses were preregistered (pre-registration available at https://osf.io/b2cn7/).

Measures and data analysis

Measures and data analysis were identical to Experiment 2a and Experiment 2b.

Method

Participants

We randomly assigned 251 participants from the Prolific online subject pool to the help-seeking, don’t-know, combination, and no-choice conditions. Compensation was the same as in Experiment 2b. We excluded the data of 23 participants (9.13%) who quit partway through the experiment. Additionally, we excluded the data of 10 participants after applying the same exclusion criteria as in Experiment 2b and the data of 6 participants who reported consulting external sources (e.g., Internet, books) during the experiment. This left 50 participants in the help-seeking condition, 55 participants in the don’t-know and combination conditions, and 52 participants in the no-choice condition. Most participants (98%) reported their everyday language to be English.

Materials and procedure

Materials were the same as in Experiment 2. The procedure was identical to Experiment 2b with the following exceptions. Instructions in the help-seeking and combination conditions explained that each question for which participants sought help would be presented in a subsequent help phase together with the response of a previous participant whose accuracy was higher than that of 80% of previous participants. In the help phase, each question appeared together with an interval that encompassed the correct value and was ostensibly provided by the previous participant.

Results

We eliminated from the data analyses 16 answers (0.22%) that participants reported not to remember when asked to make a confidence judgment, 69 answers (0.94%) with response latencies > 90 s, and 155 answers (2.10%) for which participants switched to another computer window while asked to provide answers, make confidence judgments, or submit answers/use a strategy.

Table 1 reports descriptive statistics. Conditions did not differ in confidence or accuracy, Fs < = 2.43, p > = 0.067. Participants used the available strategy less often in the help-seeking than in the don’t-know condition, t(103) = 5.43, p < 0.001, d = 1.06, and, in the combination condition, participants less often sought help than they responded don’t know, t(54) = 3.58, p < 0.001, d = 0.49. Frequencies of help seeking were equivalent across the help-seeking and combination conditions, whereas frequencies of don’t-know responses were higher in the don’t-know than in the combination condition (see Table 1).

Table 2 shows descriptive statistics conditionalized on strategy use. In the help-seeking and don’t-know conditions, a 2 (available strategy group: help seeking, don’t know) by 2 (strategy use: no, yes) mixed ANOVA on confidence revealed a significant main effect of strategy use, F(1, 81) = 539.72, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.87, indicating that participants used either strategy when their confidence was low. A significant interaction, F(1, 81) = 9.80, p = 0.002, ηp2 = 0.11, demonstrated higher confidence when participants sought help than when they responded don’t know in the respective conditions. The main effect of available strategy group was not significant, F < 1. In the combination condition, a repeated measures ANOVA revealed that confidence varied across questions for which people submitted answers, sought help, or responded don’t know, F(2, 28) = 153.61, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.92, with pairwise comparisons confirming lower confidence for help requests than for submitted answers, but higher confidence for help requests than for don’t-know responses (see Table 2).

The overlap in confidence between questions for which participants submitted answers or used a strategy was again larger in the help-seeking than in the don’t-know condition, t(81) = 2.61, p = 0.011, d = 0.59 (see Fig. 2). This was due to higher minimum confidence when using the available strategy, t(81) = 2.35, p = 0.021, d = 0.53, and lower minimum confidence in submitted answers, t(103) = 4.29, p < 0.001, d = 0.84, in the help-seeking than in the don’t-know condition. In contrast, maximum confidence when using the available strategy and in submitted answers did not differ across conditions, both t < 1. A very similar pattern occurred in the combination condition, where the overlap in confidence was larger for help requests than for don’t-know responses, t(29) = 2.43, p = 0.022, d = 0.45. This difference was due to help requests being associated with higher minimum, t(29) = 2.80, p = 0.009, d = 0.52, and maximum confidence, t(29) = 2.43, p = 0.022, d = 0.45, than don’t-know responses.

As in the previous experiments, control sensitivity (see Table 2 for descriptive statistics) was weaker in the help-seeking condition than in the don’t-know condition, t(81) = 4.23, p < 0.001, d = 0.96. Similarly, in the combination condition, control sensitivity was weaker for help requests than for don’t-know responses, t(29) = 6.18, p < 0.001, d = 1.15.

Concerning accuracy of the initial answers in the help-seeking and don’t-know conditions, a mixed 2 (available strategy group: help seeking, don’t know) by 2 (strategy use: no, yes) ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of strategy use, F(1, 81) = 106.61, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.57, indicating that strategy use was accompanied by low accuracy. No other effects were significant, Fs < 1. In the combination condition, accuracy of initial answers varied across submitted answers, help requests, and don’t-know responses, F(2, 58) = 38.16, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.57, with pairwise comparisons confirming higher accuracy for submitted answers than for help requests or don’t-know responses (see Table 2).

The accuracy of submitted answers varied across conditions (see Table 1 for the no-choice condition and Table 2 for the other conditions), F(3, 208) = 10.16, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.13. Compared to the no-choice condition, accuracy of submitted answers was higher in the help-seeking, t(100) = 3.65, p < 0.001, d = 0.72, don’t-know, t(105) = 4.98, p < 0.001, d = 0.96, and combination condition, t(105) = 5.16, p < 0.001, d = 1.00. Thus, unlike in Experiment 2, both strategic options improved output-bound accuracy.

Discussion

Using another form of help than in the previous experiments, Experiment 3 replicated the finding that confidence was negatively associated with help seeking and withholding answers and, more importantly, that this association was weaker for help seeking than for withholding answers, as reflected by reduced control sensitivity. As in the previous experiments, this pattern occurred independently of whether only one strategic option or both strategic options were available. Unlike in the previous experiments, not only the option to withhold answers but also the option to seek help improved output-bound accuracy compared to the no-choice condition. We return to this issue in the General Discussion.

General discussion

The present study focused on the metacognitive processes involved in two strategies people use to provide correct and informative answers to knowledge questions: help seeking and withholding answers. According to process models of help seeking, this research elaborated on the first three steps of help seeking, that is, recognizing that a problem exists, determining that help is needed or wanted, and deciding whether to seek help (cf. Karabenick & Berger, 2013; Karabenick & Gonida, 2018; Makara & Karabenick, 2013). As we expected on the basis of prior work (e.g., Coughlin et al., 2015; Goldsmith, 2016; Koriat & Goldsmith, 1996; Nelson & Fyfe, 2019), confidence was inversely related to the use of either strategy: Participants sought help and withheld answers when their confidence in the correctness of their initial answers was relatively low. Also consistent with prior work, people’s initial answers to questions they sought help for were often inaccurate (for a review, see Karabenick & Gonida, 2018), demonstrating that people reliably recognized their need for help. Similarly, people often withheld inaccurate answers (see, e.g., Goldsmith, 2016).

The reported experiments provided the following novel insights. First, comparing the association between confidence and strategy use across conditions revealed that the association between confidence and help seeking was weaker than that between confidence and withholding answers. This result remained when participants received monetary incentives for accurate answers, across two different populations, in two different sets of knowledge questions, and across two different forms of help. On a theoretical level, this finding is consistent with our hypothesis that help seeking is guided by considerations beyond improving the immediate accuracy of one’s answers, and more so than withholding answers. Considerations that might encourage help seeking include the wish to provide informative answers (Grice 1975, see also Goldsmith, 2016), satisfying one’s curiosity (Berlyne & Frommer, 1966; Ferguson et al., 2015; Son & Metcalfe, 2000), and receiving feedback about the accuracy of one’s knowledge (Bamberger, 2009; Nelson-Le Gall & Jones, 1990). At the same time, the wish to save time, to maintain a sense of independence and self-reliance, and to avoid failing after receiving help might discourage help seeking (Arbreton, 1998; Butler, 1998, 2006; Metcalfe, 2009; Santos et al., 2020; Nadler, 2017; Newman & Goldin, 1990; Undorf & Ackerman, 2017). Moreover, the weaker association between confidence and help seeking than between confidence and withholding answers is consistent with the large body of work showing that help seeking involves various sub-processes and is affected by multiple individual differences, situational variables, and cultural factors (e.g., Butler, 2013; Nadler, 2017; Newman, 2000; Volet & Karabenick, 2006).

Second, offering participants the choice between help seeking and withholding answers represents a significant advance in the ecological validity of experimental work on help seeking. Similar associations between confidence and help seeking when participants had only the option to seek help and when they could choose between seeking help and withholding answers suggests that these two strategies serve different functions. This finding is intriguing and deserves to be examined in future research.

Finally, the option to seek help improved output-bound accuracy (Koriat & Goldsmith, 1994, 1996)—the accuracy of answers participants chose to submit—in comparison to the no-choice condition in Experiment 3, but not in Experiment 2a and Experiment 2b. Thus, the option to seek help did not consistently improve output-bound accuracy. In contrast, the option to withhold answers improved output-bound accuracy in all experiments. We can only speculate as to why the option to seek help improved output-bound accuracy in Experiment 3, but not in Experiment 2a or Experiment 2b. Given that participants in Experiment 3 and Experiment 2b came from the same population, we can exclude the possibility that differences in output-bound accuracy resulted from differences in culture-related values or sociocultural contexts. For the same reason, individual differences such as achievement goals and motivational orientation known to affect help seeking (for reviews, see Butler, 2006; Karabenick & Berger 2013) are unlikely reasons for the observed differences in output-bound accuracy. Although the specific type of help provided differed between Experiment 3 and Experiment 2a and Experiment 2b, both types of help were instrumental in nature. If anything, higher chances of guessing the correct response in Experiment 3 than in Experiment 2a and Experiment 2b might underlie the observed differences in output-bound accuracy. Notably, however, there was no appreciable difference in the frequencies of help seeking or in the associations between help seeking and confidence across the two types of help.

In any case, the current findings shed new light on output-bound accuracy and its relevance for educational research. In educational settings, output-bound accuracy has been considered in the literature on the advantages and disadvantages of multiple-choice examinations where test takers are instructed to withhold answers and scoring methods penalize guessing (e.g., Higham & Arnold, 2007; McHarg et al., 2005; Muijtjens et al., 1999; Nickerson et al., 2015). The current study suggests that output-bound accuracy may be relevant for a much wider range of educational situations. Thus, it may be worthwhile to examine the interplay between help seeking and output-bound accuracy from educational and developmental perspectives (see Koriat & Ackerman, 2010, for evidence that the option to withhold answers improves output-bound accuracy in children as young as 7 years of age).

One compelling advantage of seeking help over withholding answers is that seeking help can increase the correctness of answers while maintaining high informativeness (maxims of quality and quantity, Grice, 1975; see also Goldsmith, 2016). In light of this argument, it was somewhat surprising that, except in Experiment 1, participants sought help less often than they responded don’t know. More consistent with this proposal was the finding that frequencies of help seeking were similar when one or two strategic options were available, whereas frequencies of withholding answers were lower when both strategic options were available (see Experiment 2a and Experiment 3). Low frequencies of help seeking are, however, in line with numerous studies showing that people refrain from requesting needed help (e.g., Butler, 1998, 2008; Roll et al., 2011; Ryan et al., 2009; Zusho & Barnett, 2011).

In the combination conditions of the current experiments, participants may have withheld answers in order to avoid seeking help. If so, we should see less help seeking in the combination condition than in the help-seeking condition. Inconsistent with this prediction, all relevant experiments showed similar frequencies of help seeking across the two conditions. Also, in the combination condition, correlations between the frequencies of help seeking and withholding answers were negligible and did not differ from zero, Experiment 2a: r = 0.06, t < 1, Experiment 2b: r = -0.22, t(47) = 1.52, p = 0.135, d = 0.22, Experiment 3: r = -0.14, t(53) = 1.05, p = 0.301, d = 0.14. Apart from help avoidance, participants may have been somewhat reluctant to seek help because this would lead to spending more time on the study (for evidence from an academic setting, see Newman & Goldin, 1990). Also, we suspect that emphasizing a social motivation related to providing answers (e.g., the social value of responding to a specific person; Sidi et al., 2018) may promote a relative preference for help seeking over withholding answers.

Our findings on control sensitivity, that is, the within-participant correlation between confidence and strategy use, have important implications for research on metacognition. This is the first study to establish weaker control sensitivity for help seeking than for withholding answers. Also, intermediate levels of control sensitivity in the range of -0.15 to -0.70 are a novel finding. In prior studies where participants had the option to withhold answers, control sensitivity in healthy young adults was usually close to perfect. These studies found only two manipulations that impaired control sensitivity. First, administering benzodiazepines reduced the reliance of withholding answers on subjective confidence (Massin-Krauss et al., 2002; Mintzer et al., 2010). Second, participants who studied expository texts from screen rather than from paper showed reduced reliance of study time allocation on predictions of future test performance (Ackerman & Goldsmith, 2011). In the current study, control sensitivity was very high for withholding answers and significantly lower for help seeking. This difference reveals that high control sensitivity cannot be taken for granted, as is often done when assuming that metacognitive monitoring drives behavior (see, e.g., Nelson & Narens, 1990). Moreover, it suggests that control sensitivity and the factors affecting it need to be examined separately for various metacognitive control strategies.

It is instructive to compare our findings on the interrelations between help seeking, confidence, and answer accuracy with findings by Ferguson et al. (2015). In their study, participants from the experimental group could look up answers to knowledge questions on the Internet after indicating that they did not know the answer. In contrast, participants from the control group entered “NA” into the answer field if they did not know the answer. Mirroring results obtained in the present study, the answers experimental participants volunteered without searching the Internet revealed higher accuracy than the answers given by control participants, reflecting higher output-bound accuracy in experimental than control participants. However, there was also one important difference between Ferguson and colleagues’ (2015) results and the present results. Ferguson and colleagues’ (2015) experimental participants reported lower feeling-of-knowing judgments than control participants. In contrast, we found similar levels of confidence judgments across participants who did or did not have the option to seek help. This difference in results might suggest that the availability of strategic options has differential effects on feeling-of-knowing judgments and confidence judgments. Of course, further work will be needed to evaluate this hypothesis. However, investigating this possibility has the potential to advance our understanding of the interplay between metacognitive monitoring and control.

Future directions

In this study, we aimed to generalize findings across participants, materials, experimental settings and procedures, and forms of help. Nevertheless, further investigation of generalizability and boundary conditions is in place. In particular, in all our experiments, the help offered to participants was instrumental in nature: It alleviated a current state of need and assisted participants to achieve independently, but did not expedite task completion. It has been proposed in previous research that associations between perceived need for help and help seeking are more pronounced for seeking instrumental help than for seeking work-avoidant and maladaptive executive help (for reviews, see Karabenick & Berger, 2013; Newman, 2006). Also, people’s willingness to seek instrumental or, alternatively, executive help in academic settings was found to be closely related to motivational variables. For instance, instrumental help seeking was common among learners with a mastery goal orientation, high levels of self-efficacy, and high self-perceived competency (for reviews, see Butler, 2006; Karabenick & Berger, 2013). In contrast, learners who are threatened by seeking help, have a performance goal orientation, and perceive themselves as academically incompetent, prefer to seek executive help (for reviews, see Butler, 2006; Karabenick & Berger, 2013). Consequently, it remains to be seen whether the present findings on the association between subjective confidence and help seeking generalize to executive help. Future research might also examine the association between subjective confidence and selecting among levels of help that fall along a continuum ranging from instrumental to executive help (e.g., Aleven et al., 2006; Roll et al., 2011, 2014). More generally, supplementing the current paradigm with individual differences, situational variables, and cultural factors that are known to affect help seeking (e.g., Butler, 2013; Nadler, 2017; Newman, 2000; Volet & Karabenick, 2006) is a worthwhile pursuit.

The materials used in the present experiments were two different sets of general-knowledge questions in different languages. Both sets were similar in that they covered a broad range of topics, required quantitative-numeric responses, and had pretested accuracy rates between 20 and 80%. The two sets of general-knowledge questions yielded very similar results, suggesting that the present findings do not depend on the specific general-knowledge questions we used. Whether our conclusions hold for other materials and tasks (e.g., retrieval of newly learned information from episodic memory) is a question for future research.

The present experiments all used contingency reward systems where incorrect responses and help requests had costs. As explained in the introduction, imposing a cost for help requests helped to increase the external validity of our task design and to provide a strong test of our predictions. Clearly, future studies should use alternative ways of ensuring external validity and motivation.

Finally, our experiments focused on the immediate consequences of seeking help and withholding answers. Our findings suggest that some of the considerations that guided help seeking did not improve the accuracy of people’s answers. An intriguing question is whether and to what extent particular considerations improve answer accuracy in the long term.

Conclusion

The present study revealed important similarities and differences in the relationship between confidence and seeking help as compared to the relationship between confidence and withholding answers. It has thereby advanced the understanding of the metacognitive monitoring processes involved in seeking help and withholding answers and, consequently, the micro-level of self-regulated learning (cf. Greene & Azevedo, 2009; Karabenick & Gonida, 2018; Volet & Karabenick, 2006). This study represents a significant advance in the ecological validity of experimental work on help seeking and withholding answers, because participants had the possibility to choose between two strategic options. Consequently, it may help to bridge the gap between experimental work on help seeking and withholding answers and research on these topics in educational and other real-life settings.

References

Ackerman, R., Bernstein, D. M., & Kumar, R. (2020a). Metacognitive hindsight bias. Memory and Cognition, 48, 731–744. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13421-020-01012-w

Ackerman, R., & Goldsmith, M. (2008). Control over grain size in memory reporting—with and without satisfying knowledge. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 34, 1224–1245. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0012938

Ackerman, R., & Goldsmith, M. (2011). Metacognitive regulation of text learning: On screen versus on paper. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 17, 18–32. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022086

Ackerman, R., & Thompson, V. A. (2017). Meta-reasoning: Monitoring and control of thinking and reasoning. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 21, 607–617. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2017.05.004

Ackerman, R., Yom-Tov, E., & Torgovitsky, I. (2020b). Using confidence and consensuality to predict time invested in problem solving and in real-life web searching. Cognition, 199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2020.1042482020.104248

Ackerman, R., & Zalmanov, H. (2012). The persistence of the fluency-confidence association in problem solving. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 19, 1187–1192. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-012-0305-z

Aleven, V., McLaren, B., Roll, I., Koedinger, K. (2006). Toward meta-cognitive tutoring: A model of help seeking with a cognitive tutor. International Journal of Artificial Intelligence in Education, 16, 101–128

Aleven, V., Stahl, E., Schworm, S., Fischer, F., Wallace, R. (2003). Help seeking and help design in interactive learning environments. Review of Educational Research, 73, 277–320. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543073003277

AlMahmoud, T., Regmi, D., Elzubeir, M., Howarth, F. C., & Shaban, S. (2019). Medical student question answering behaviour during high-stakes multiple choice examinations. International Journal of Technology Enhanced Learning, 11, 157–171. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJTEL.2019.098777

Arbreton, A. (1998). Student goal orientation and help-seeking strategy use. In S. A. Karabenick (Ed.), Strategic help seeking. Mahwah: Erlbaum

Bamberger, P. (2009). Employee help-seeking: Antecedents, consequences and new insights for future research. In J. J. Martocchio & H. Liao (Eds.), Research in personnel and human resources management: Vol. 28 (pp. 49–98). https://doi.org/10.1108/S0742-7301(2009)0000028005