Abstract

Importation in fictional discourse is the phenomenon by which audiences include information in the story over and above what is explicitly stated by the narrator. This paper argues that importation is distinct from generation, the phenomenon by which truth in fiction may outstrip what is made explicit, and draws a distinction between fictional truth and fictional records. The latter comprises the audience’s picture of what is true according to the narrator. The paper argues that importation into fictional records operates according to principles that also govern ordinary conversation. An account of fictional records as a species of common ground information is proposed. Two sources of importation are described in detail, presupposition accommodation and conversational implicatures. It is shown that presuppositions are both mandatorily imported and mandatorily generated. By contrast, conversational implicatures are neither mandatorily imported nor mandatorily generated. The paper distinguishes conversational implicatures from contextual inferences. Both rely on background assumptions, yet conversational implicatures moreover depend on assumptions concerning Gricean cooperation.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Questions about truth in fiction have been at the center of the philosophical literature on fiction at least since Lewis’s classic paper (Lewis 1983 [1978]). Most of the debate has been over so-called generation principles (Walton 1990; Woodward 2011; Friend 2017). Such principles are designed to delineate what is true in a fiction over and above what is explicitly stated by the narrator. For instance, it has been discussed whether it is true in the Sherlock Holmes stories that Holmes has exactly two nostrils (Lewis 1983 [1978]), whether it is true in Nabokov’s Pnin that there are exactly two trillion stars in the night sky (Currie 1990; Woodward 2011), or whether it is true in James’s The Turn of the Screw that ghosts exist (Currie 1990).Footnote 1

The focus on truth in fiction and generation principles has sometimes lead the literature on fiction to pay less attention to the question of how audiences arrive at an understanding of the story. The mechanism by which audiences expand stories based on what the narrator makes explicit is often known as importation (Gendler 2000). It is fair to say that there has been more interest in generation than in importation. To be sure, how audiences interpret what the narrator conveys has been discussed by, among others, Currie (1990, ch. 3), Byrne (1993), Phillips (1999), Davies (2015), Stock (2017, ch. 2). Yet all of these writers do so ultimately in the service of developing theories of truth in fiction. Moreover, since the influential work of Walton (1990), this literature has been concerned with what audiences are prescribed to imagine, or make-believe, by fictional works.

Yet most fiction is conveyed and understood through linguistic utterances, spoken or in writing, and storytelling is a form of communication. The way in which audiences to fictions assemble the information that make up the story is a special case of the way we gather information from the speech of others. Consequently, there is a need for studying importation as a linguistic phenomenon.

This paper has two specific goals. The first is to argue that importation and generation are independent. Something that is not made explicit by the narrator may be part of the story, and yet it may not be true in the fiction. And something may be true in a fiction even though it is not part of the story. Imported information is not always generated. Generated information is not always imported.

The second goal is to show that importation operates on principles that likewise govern the way we understand each other in ordinary conversation. I consider two sources of importation in detail. The first is presupposition accommodation, the second is conversational implicature. Both are ubiquitous mechanisms for fleshing out stories beyond what is explicitly stated by the narrator. Yet we will see that there are differences between how these function in fictional discourse as opposed to ordinary conversation. Both presuppositions and conversational implicatures in fictional discourse are mandatorily imported. The audience have no option to reject them. Yet while presuppositions are also mandatorily generated, conversational implicatures are not. While presuppositions are true in a fiction if the content that triggered them is, conversational implicatures may be false in a fiction even if the content from which they are inferred is true in the fiction.

I will argue that conversational implicatures in fictional discourse rely on the audience taking the narrator to obey Gricean principles of cooperation. As such, conversational implicatures can be distinguished from what I will call contextual inferences. The latter are inferred independently of assumptions about cooperation. Yet I will argue that both kinds of inferences depend on background information that is typically the result of default importation. That is, information taken to be part of the story even though it has neither been made explicit nor imported.

I develop a way of understanding stories and importation within the framework for theorizing about communication originating in the work of Stalnaker (1999 [1970], 1999 [1978], 1999 [1998], 2002), Karttunen (1974) and others. In this tradition communication is seen as relying on a collection of shared information, called the common ground, which acts both as support for utterance interpretation and as storage for information conveyed by the participants. Correspondingly, on the view I will argue for here, audiences engage with fictional stories by collecting information in what I will call fictional records. Fictional records function like ordinary common grounds in storing what has previously been communicated which in turn serves as background information for subsequent utterances by the narrator.Footnote 2

Section 2 distinguishes between what is made explicit by the narrator, what is part of the story, and what is true in the fiction, before introducing the notions of importation and generation that I am concerned with. In Sect. 3 I lay how I propose to understand stories and importation as a species of common ground information. Section 4 examines presupposition accommodation in relation to importation and generation. Section 5 turns to conversational implicatures and contextual inferences in fictional discourse.

2 Importation and generation

2.1 Explicit content, fictional records, and fictional truth

It is standard to note that truth in fiction is independent of what we are explicitly told by the narrator. Davies (1996) gives a clear statement:

Being explicitly stated in the text of S is neither necessary nor sufficient for being true in S, however. It is not necessary because we must allow for at least some things to be true in the story though neither explicitly stated nor immediately derivable from what is explicitly stated. It is not sufficient, on the other hand, because we want to allow for deceptive or deceived narrators, or for narrators who consistently understate, exaggerate, or employ irony. (Davies 1996, 44)

In other words, we should distinguish between what is true in a fiction and what we are explicitly told by the narrator. Following common practice, I refer to the phenomenon by which what is true in a fiction may outstrip what we are told by the narrator as generation. For instance, the fact that it is true in, say, Doyle’s A Study in Scarlet that Holmes has exactly two nostrils (if it is) is the result of generation.

I want to highlight a similar distinction at the level of what we are told by the narrator. It may be part of what we are told by the narrator that p, even though the narrator has not explicitly said that p. I refer to the process by which information is included in stories beyond what is made explicit as importation. I will argue that importation is distinct from generation. Something that is not explicitly stated by the narrator may be part of what we are told even if it is not true in the fiction. Conversely, something may be true in the fiction, even though it is not part of what we are told, either explicitly or implicitly.

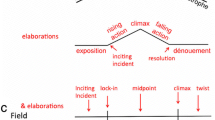

As this suggests, we should recognize three different levels. First, there is what the narrator explicitly says. I call this explicit content. Second, there is what I will call the fictional record, comprising what we are told by the narrator (and other things, as we will see later).Footnote 3 Finally, both should be distinguished from fictional truth, what is true in the fiction. The relation between these three levels can be represented like this:

I now go on to illustrate the differences between these categories.

Consider a simple example. Imagine that the narrator of a fictional story says,

What the narrator explicitly said was that everyone went to the party and that Paul had to work. Yet the narrator also conveyed (2).

If (1) was uttered in an ordinary, non-fictional conversation, we would say that (2) was conversationally implicated by the speaker.Footnote 4 This raises the issue of whether the familiar phenomenon of conversational implicature can be said to occur in the case of fictional discourse.

I will argue later (see 5.1) that inferences like the one from (1) to (2) arise because audiences assume that narrators are being cooperative, in the sense of observing principles of cooperation like the Gricean maxims. For this reason, I will call inferences of this kind on the part of audiences to fictions “conversational implicatures.”

Narrators sometimes say things that are true in the fiction but which give rise to conversational implicatures that are false in the fiction. Suppose that it is later revealed to us that while Paul did have to work, he nevertheless went to the party like everyone else. We would think that the narrator was being misleading in telling us (1). The reason is that we think that (2) is part of what we were told about Paul. If we did not think that (2) was part of what the narrator conveyed to us by explicitly saying (1), we would not think that she had been misleading when it turns out that (2) is false in the fiction.

In this case it is true in the fiction that Paul went to the party. Yet it is not part of the fictional record that Paul went to the party. Indeed, it is part of the fictional record that he did not go to the party. In other words, while (2) is imported into the fictional record of the story, (2) is not generated as fictional truth.

Here is an example from an actual fiction that has been discussed by Sainsbury (2014). Consider the following passage from Agatha Christie’s The Murder of Roger Ackroyd:

Sainsbury writes,

It is tempting to suppose that it is part of the content of this passage that Dr. Sheppard’s interlocutor on the telephone said that Ackroyd had been murdered. Twenty-two chapters pass before we are disabused of this interpretation. (Sainsbury 2014, 281)

Like others (e.g. Lewis 1983 [1978]; Currie 1990) Sainsbury is using “content” to mean what is true in the fiction. If one uses “content” this way, it is not part of the content of The Murder of Roger Ackroyd that Parker said on the phone that Ackroyd had been murdered.

However, it is undeniably part of what the narrator, Dr. Sheppard, conveyed to us that this is what happened. That is why we are surprised later on when we find out that it did not. At the same time, it is not explicitly stated in (3) that Parker said on the phone that Ackroyd had been murdered. Rather, as I will argue later (in 5.1), it is a conversational implicature inferred on the basis of what is explicitly said.

It is part of the fictional record of The Murder of Roger Ackroyd that Parker said on the phone that Ackroyd had been murdered. Yet even though this information is imported into the fictional record, it is not true in The Murder of Roger Ackroyd. In other words, something that is not explicit may be part of the story, even though it is not true in the fiction.Footnote 5 Such information is imported but not generated. The plots of novels like The Murder of Roger Ackroyd rely on us being able to keep track of this difference and to compare the fictional record with what is ultimately revealed as fictionally true.

Correspondingly, something may be generated as fictional truth, even though it is not part of what we are told by the narrator, either explicitly or implicitly. For instance, suppose you agree that it is true in A Study in Scarlet that Holmes has exactly two nostrils. Even so, you might not think that this is part of the fictional record of A Study in Scarlet. We can perfectly well make sense of the story without thinking that it is part of what Watson tells us that Holmes has exactly two nostrils. Someone who has never thought of Holmes’s nostrils has not thereby missed anything about A Study in Scarlet. (We return to this in 5.3.)

In the next section I will argue that fictional records can be understood as a species of common ground information. Before moving on to that, I want to end this section by commenting on an issue concerning explicit content itself.

2.2 Underdetermination and explicit content

Many philosophers of fiction have pointed out that what we are calling explicit content is itself the result of a process that takes as its input the sentences that make up the text in the case of written stories or the utterances of an story teller.Footnote 6 What they have in mind is the analogue of the class of phenomena familiar from debates in philosophy of language and linguistics over the semantics-pragmatics distinction, often discussed under the heading of underdetermination. The central question in this literature concerns how utterances of natural language sentences, given the context, determine truth-conditional contents, typically referred to as what is said.Footnote 7

Given that fictional stories of the kind we are interested in here are made up of utterances, it is unsurprising that issues concerning underdetermination arise for fictional discourse just as for ordinary talk. Currie (2010) gives an example familiar from the semantics-pragmatics literatureFootnote 8:

if it is written into the story that Watson, the narrator, declares ‘by this time I had had breakfast’, what is explicit? That at some point in his life Watson had had breakfast? That would be to adopt a very restricted sense of ‘what is made explicit’. A more reasonable sense would allow us to say that Watson made it explicit that he had had breakfast that morning [...]. (Currie 2010, 13)

In other words, ultimately we need a way of accounting for the process, usually known as enrichment, that takes us from the narrator’s use of sentences like (4a) to explicit contents like (4b).

Enrichment is not the same as importation. Even if the “literal” statements of the narrator sometimes need to be enriched in order to arrive at explicit content, information is routinely imported into the fictional record over and above what is made explicit in this way.

Correspondingly, few views on the semantics-pragmatics distinction will count the kind of information that is typically imported into fictional records as part of what is said, or the truth-conditional content, of natural language utterances. For instance, on one approach, what is said by a sentence or utterance, in context, consists of what is needed for truth-evaluability and nothing more. Recanati (1993) states this criterion as follows:Footnote 9

Minimal truth-evaluability principle: A pragmatically determined aspect of meaning is part of what is said if and only if its contextual determination is necessary for the utterance to be truth-evaluable and express a complete proposition. (Recanati 1993, 242)

Given the minimal truth-evaluability principle (henceforth, MTP), conversational implicatures are not part of what is said, regardless of the context. For instance, it is not part of what is said by “Paul had to work” that Paul did not go to the party, since the latter is not necessary for the truth-evaluability of the former in any context.

Similarly, MTP arguably does not imply that standard presuppositions are part of what is said. It is uncontroversial that, for instance, the truth of (5b) is necessary for the truth or falsity of (5a).

We will see later (see 4.3) that this is mirrored in the behavior of presuppositions in fictional discourse with respect to generation. But this is not the same as saying that the “contextual determination” of (5b) is necessary for the truth-evaluability of (5a). We do not need to use the context to figure out that Susan was not crying before in order to be able to assess whether it is true or false that she started crying. Indeed, (5b) arguably is not a “pragmatically determined aspect” of the meaning of (5a).

Rather, standard presuppositions of this kind are widely recognized as lexically encoded.Footnote 10 MTP is compatible with agreeing that some information is lexically encoded and yet not part of what is said. The remit of MTP, and similar principles, is information that needs to be determined by extra-linguistic contextual clues in order for the relevant utterance to be truth-evaluable.

Correspondingly, other, more liberal views than MTP do not count either conversational implicatures or presuppositions as part of what is said. For instance, on the recent account defended by Schoubye and Stokke (2016) and Stokke (2018), what is said is determined as an answer to a salient question under discussion, in the sense of Roberts (2012), which stands in an entailment relation to the purely compositional meaning of the relevant sentence. Yet on this view it is not part of what is said by “Paul had to work” that Paul did not go to the party, since the latter does not stand in any entailment relation to the compositional meaning of the former. Nor are presuppositions part of what is said since they do not fulfil the relevant criterion for being an answer.Footnote 11

Because my interest here is in fictional records and importation, and their relation to fictional truth and generation, I will not be concerned with the issue of enrichment or other pragmatic determinants of explicit content. For the remainder of this paper, I assume that we can delineate explicit content in some way that excludes both conversational implicatures and presuppositions.

3 Fictional records

3.1 Common grounds and corpora

We have seen that audiences to fictional stories infer conversational implicatures from what the narrator explicitly says. This suggests that importation as a device for filling out fictional records operates according to principles that also underlie ordinary conversations. At least to a large extent, we interpret what the narrator of a fictional story tells us in ways that mirror how we interpret each other in everyday discourse settings. Given this, it is convenient to think of fictional records as analogous to information that is shared among participants in ordinary, non-fictional conversations.

On the familiar picture originating in the work of Stalnaker (1999 [1970], 1999 [1978], 1999 [1998], 2002, 2014), communication relies on shared background information, called the common ground, which serves both to support interpretation and as a storage for new information that is added during the conversation. Information is added to the common ground through various means, including assertion, presupposition accommodation, conversational implicature, or by being manifestly observable. In turn, speakers can assume that common ground information is available to help make sense of subsequent utterances.

A fictional record functions like a common ground. That is, a set of propositions playing this dual role with respect to what the narrator communicates. Yet there are obvious differences between ordinary common grounds and fictional records, reflecting the differences between ordinary conversations and fictional discourse. For one thing, there is only one speaker in the latter case. Correspondingly, the fictional record is the audience’s picture of how the narrator represents things. By contrast, the common ground of an ordinary conversation registers what is commonly believed to be accepted by the participants.

Consider an analogy. A witness gives testimony in a court of law. As a jury member, you need to build up an idea of how the witness is representing the relevant events while you are listening to their account. This involves, among other things, putting together a set of propositions that make up the information that you think the witness conveyed. In turn, you need to allow this information to play the dual role played by common ground in ordinary conversations. You need to draw on it for making sense of what the witness says. A fictional record is analogous to this cache of information that you incrementally assemble on the basis of the witnesses’s utterances and which supports the interpretation of subsequent material.

To make this more precise, I follow Currie (2010) in adopting Lewis’s (1982) notion of a corpus of information. As characterized by Currie,

A corpus is a body of representations, emanating from a more or less unified source—a single individual, a team of experts, a tradition—and in which we may have a more or less systematic interest. [...] Corpora are things according to which something or other is true; it may not be raining in actuality, but it may be raining according to someone’s belief, according to the bulletin from the weather bureau, according to a story, fictional or non-fictional. (Currie 2010, 8)

Along these lines, we characterize the fictional record of a story as follows:

Fictional Record

The fictional record of a story s for an audience A =df the set of propositions p such that all members of A believe that p is true according to the narrator of s.

So, a fictional record comprises the audience’s beliefs about what is true according to the narrator.Footnote 12 Or, to use Currie’s term, the audience’s beliefs about the corpus “emanating from” the narrator. (We will see later that, just as with ordinary common ground information, fictional records include more than just what has been communicated by the narrator in a narrow sense.)

It is crucial to be clear about what we mean by “true according to the narrator” here. In particular, that p is true according to the narrator does not mean that the narrator, in the fiction, believes that p, let alone that p is true in the fiction.Footnote 13 As Currie says,

When something is true according to a corpus, the agents from which it emanates are not always committed to its truth; that will be so for belief systems and historical texts, it may be so for weather reports, it is not so for fictional stories. Representing-as-true and being-committed-to-truth are different. (Currie 2010, 8)

The fictional record of The Murder of Roger Ackroyd includes the information that Parker said on the phone that Ackroyd had been murdered. This is part of how things are in the fiction according to the narrator, Dr. Sheppard. Yet we do not mean that Dr. Sheppard, in the fiction, believes that Parker said on the phone that Ackroyd had been murdered, nor that this is true in the fiction. What we mean is that it is true according to how Dr. Sheppard represents things to us. (At least until he reveals the truth. We return to this later.)

Similarly, the story of a murder might be one way according to a witness’s testimony, another way according to what the witness actually believes, and yet it might be that none of these adequately represents the truth of what in fact happened. Just as in ordinary situations, as audiences to fictions we are aware of such differences, and the fictional record merely registers how we think the narrator represents what things are like in the fiction.

On the view I am sketching, fictional records qua corpora play the same kind of dual role that is played by the common ground for ordinary, non-fictional communication. In reading or hearing a fictional story, a cache of information is incremented with what the narrator makes explicit and through various means of importation. In turn, the audience draws on this information to make sense of the story.

This proposal is similar to Stalnaker’s (1999 [1988]) suggestion that what he calls “derived contexts” can likewise play both these roles. Yet Stalnakerian derived contexts delineate what the basic common ground says about what is the case according to some corpus of information, such as someone’s beliefs. For instance, the derived context representing someone’s beliefs will be the set of propositions p such that it is common ground that they believe that p. Since I am not discussing situations in which it makes a difference what is common ground about the relevant story, I refrain from discussing fictional records as full-blooded Stalnakerian derived contexts. It is easy to see that such a notion can be defined, that is, as the set of propositions p such that it is common ground that p is true according to the narrator.

In the next two sections we will see how this framework provides a way of understanding presupposition accommodation and inferences in fictional discourse. Before finishing this section, I will comment on some consequences of seeing fictional records in the way just outlined.

3.2 Fictional records and audiences

We have characterized fictional records as relative to audiences, that is, as comprising how an audience think the narrator represents things. Given this, in principle, the fictional record of, say, The Murder of Roger Ackroyd may differ from audience to audience. By contrast, one might think that how Dr. Sheppard represents things to be in The Murder of Roger Ackroyd is a fixed matter, and does not vary from reading to reading.Footnote 14

I want to make three comments on this. First, since the fictional record is distinct from fictional truth, the above characterization of fictional records does not imply that what is true in a fiction varies depending on the audience. Indeed, I agree with the standard view on this issue, originally proposed by Lewis (1983 [1978]):

What was true in a fiction when it was first told is true in it forevermore. It is our knowledge of what is true in the fiction that may wax and vane. (Lewis 1983 [1978], 272)

As I have argued, it might be part of the record of a story that Paul did not go to the party, even if that is not true in the fiction. Hence, this view is not committed to the view that fictional truth is relative to particular audiences.

Second, the framework I am sketching is compatible with an “objective” notion of fictional records, even if still distinct from fictional truth. In other words, if one thinks that there is a fact of the matter about what the narrator of The Murder of Roger Ackroyd conveyed, even though this objective fictional records is distinct from what is true in the novel, my account can straightforwardly accept that.Footnote 15 If one wants, one can distinguish between the corpus that is in fact constituted by how Dr. Sheppard represents things to us in the novel and how different audiences construe this on different occasions.

Third, defining fictional records relative to audiences corresponds to the definition of common ground information for ordinary conversations as relative to conversational participants. That definition does not prevent us from discussing, for instance, how conversational implicatures, presuppositions, or assertions interact with common ground information. What we are discussing in these cases is how things typically or usually work. Yet we acknowledge that there may be unusual conversations in which, for instance, a conversational implicature does not become common ground.

How a particular audience think of the record of a fictional story on a particular occasion of reading or hearing is ultimately an empirical question. For instance, one can ask what Jane thought Dr. Sheppard conveyed when she read The Murder of Roger Ackroyd while on holiday in the summer of 2019. Yet what we are after here is a more generalized notion. Just as we are normally interested in discussing effects on the common ground of conversations while abstracting away from particular, actual conversations, we are interested in how fictional records develop while abstracting away from particular, actual readings or hearings. For this reason I will continue to speak of the fictional record of a particular fiction.

4 Presupposition accommodation in fictional discourse

In this section I consider presupposition accommodation in fictional discourse. I present an example and comment on two presuppositions it involves. I then go on to argue that presupposition accommodation is an example of mandatory importation. Finally, I turn to presuppositions in relation to the distinction between importation and generation.

4.1 Presupposition accommodation

A central motivation for the common ground picture of communication is the idea that some utterances require that the common ground fulfill certain conditions.Footnote 16 The classic example of this are presuppositional utterances, which are seen as requiring that what is presupposed be either already common ground or accommodated. Take our earlier example:

(5a) presupposes (5b) and is only felicitous in a context where the latter is either already common ground or can be accommodated.Footnote 17 In other words, when an utterance of (5a) is made, if the participants are not already taking it for granted that Susan was not crying before, usually this information will be added to the common ground. In turn, the resulting adjusted common ground is updated with the information that Susan started crying.

Presupposition accommodation is a common mechanism for importation in fictional discourse. Narrators very often say things that presuppose something we have not yet been told, thereby making us include it in the fictional record. Consider this sentence from A Study in Scarlet:

As it does in ordinary conversation, (6) presupposes (7).Footnote 18

At the same time, (6) is the first appearance of Holmes’s pipe in A Study in Scarlet, itself the first appearance of Sherlock Holmes to the reading public. So, just as in a non-fictional conversation, the presupposition that Holmes has a pipe must be accommodated. In other words, (7) is imported and included in the fictional record as a result of (6). In turn, it will be included in the fictional record that Holmes has a pipe.

In addition to the information that Holmes has a pipe, (6) presupposes (8).Footnote 19

Yet the information that Holmes was sitting down is not part of the explicit content of the text preceding (6). Watson tells us,

It was upon the 4th of March, as I have good reason to remember, that I rose somewhat earlier than usual, and found that Sherlock Holmes had not yet finished his breakfast. (Doyle 1981 [1887], 23)

After this a discussion between Watson and Holmes follows. Yet up until the occurrence of (6), we are not told anything about whether Holmes was sitting down or not, only that he “munched silently at his toast.” (loc. cit.) Hence, another result of (6) is to adjust the fictional record to include (8).

Dr. Watson’s utterance of (6) has the effect of adding to the fictional record that Holmes has a pipe and that he was sitting down. Both of these pieces of information are included in the fictional record as a result of presupposition accommodation. In turn, the resulting fictional record is then further incremented with the explicit content that Holmes rose and lit his pipe. So, more intuitively, on reading (6) the audience will think that, according to Watson, Holmes, who had been sitting down eating breakfast, stood up and lit a pipe that he had.

4.2 Mandatory importation

As illustrated by the simple example of (6), it is easy to see that, in general, a significant part of fictional records is imported via presupposition accommodation. This parallels ordinary conversation in which presupposition accommodation is likewise a ubiquitous mechanism by which information becomes common ground.

Yet there are differences between the way presupposition accommodation behaves in fictional discourse as opposed to ordinary conversation. One difference is that audiences to fictional stories have no authority to reject particular presuppositions. Dialogues like (9) frequently occur in everyday talk.

In this case the presupposition that A has a Porsche is not accommodated, and hence does not become common ground. By contrast, presuppositions in fictional discourse must be accommodated, that is, presuppositions are mandatorily imported.

For instance, when reading (6), there is no way the audience can refuse to include in the fictional record that Holmes was sitting down. To be sure, they might misunderstand what the narrator says, they might decide to stop reading, they might lose interest, get distracted, or the like, and so they might happen not to adjust the fictional record appropriately. Such cases correspond to ordinary conversations being discontinued for various haphazard reasons. Yet there is no parallel phenomenon to (9) for presuppositions in fictional discourse. If one wants to continue one’s engagement with the story, one must accommodate any presuppositions of what the author conveys.

As we will see next, in the case of presuppositions, mandatory importation is paralleled by the behavior of presuppositions with respect to fictional truth.

4.3 Mandatory generation

I argued earlier (see 2.1) that importation and generation are distinct processes. Something may be imported into the fictional record and yet not be true in the fiction. This applies to presuppositional content as well. Presuppositions may be imported without being generated. We said that, as a result of (6), the audience will think that, according to Watson, Holmes has a pipe and was sitting down. Yet we can imagine a version of A Study in Scarlet in which Watson is confused and Holmes was not sitting down or does not have a pipe.

However, the mandatory importation of presuppositions in fictional discourse does have a parallel in terms of generation. Following the standard notation by which \(A_B\) is a sentence that asserts that A and presupposes that B, presuppositions are mandatorily generated in the following sense:

Mandatory Presupposition Generation (MPG)

\(A_B\) is true or false in a fiction f only if B is true in f.

MPG is not surprising. It is just a statement of the orthodox view of presuppositions qua constraints on truth-values.Footnote 20 It is uncontroversial that, for example, if Susan was already crying, it is neither true nor false that she started crying.

To illustrate further, note that MPG does not imply that any presupposition triggered by what the narrator says is true in a fiction. Similarly, other entailments of what the narrator says are not always true in a fiction. An unreliable narrator may say something that presupposes something else, and neither the former nor the latter may be true in the fiction.Footnote 21 The fictional record is distinct from fictional truth. Instead, according to MPG, if a presuppositional claim is true in a fiction, then so is its presuppositions. The same holds for entailments more generally. In other words, mandatory generation does not hold for what a narrator explicitly says. In principle, anything a narrator explicitly says may be false in a fiction. Rather, the phenomenon encapsulated by MPG is that presuppositions are generated along with their triggers, but only when the latter are themselves generated.

Correspondingly, even though fictional stories are notoriously permissible in terms of allowing outlandish states of affairs and highly counterintuitive happenings, it is plausible to think that there cannot be a fiction in which someone who was already crying started crying. There is no version of A Study in Scarlet in which Holmes rose and lit his pipe although he was not sitting (or lying, etc.) down and does not have a pipe.

To be sure, as is routinely recognized, in some fictions what the narrator tells us contains inconsistencies. Indeed, there are fictions in which the narrator makes an explicit presuppositional utterance \(A_B\) but also tells us that not-B. Consider, for instance, the opening of Murakami’s Killing Commendatore:

Today when I awoke from a nap the faceless man was there before me. [...] He took off his hat that hid half of his face. Where his face should have been, there was nothing, just the slow whirl of a fog. (Murakami 2018, Prologue)

The use of his face presupposes that the man had a face. Yet the passage also tells us explicitly that the man did not have a face. For simplicity, let us say that the narrator explicitly tells us (10a), thereby presupposing (10b), while also explicitly telling us (10c).

While giving an account of inconsistent fictions is far beyond the scope of this paper, I want to briefly comment on such cases in relation to what I have argued above.Footnote 22

First, mandatory importation implies that if (10a) becomes part of the fictional record, so does (10b). Indeed, it is plausible to think that if the audience take the former to be part of what the narrator tells them, they also take the latter to be part of what they are told. But moreover, there is nothing to prevent us from accepting that (10c) also becomes part of the fictional record. Given what we said earlier fictional records are sets of propositions. Such sets may contain contradictory propositions.Footnote 23

Indeed, in cases of this kind, it is plausible to say that while the audience think that p is true according to the narrator, they also think that not-p is true according to the narrator. This is not an inconsistent set of beliefs on the part of the audience, since it does not imply that they both think that p (or not-p) is true according to the narrator and also do not think that. Similarly, you might think that a witnesses’s statement both represents the murder as having been committed at 8 p.m. and as having been committed at 8 a.m. The witness’s account is inconsistent. But your beliefs may not be. In other words, our account can accept that all of (10a), (10b), and (10c) are imported into the fictional record for Killing Commendatore.

Second, the issue of what is true in Killing Commendatore is more complicated. According to MPG, if (10a) is true in Killing Commendatore, so is (10b). Indeed, it is hard to deny that if the man’s hat hid half his face, then he had a face. But if (10c) is also true, this would seem to imply that (10b) is false. If so, MPG entails that (10a) is neither true nor false. This is an instance of the puzzle posed by inconsistent fictions. As such, there can be different approaches to it.

If one is sympathetic to Lewis’s (1983) preferred “method of union,” one can argue that there is a consistent fragment of Killing Commendatore in which both (10a) and (10b) are true.Footnote 24 Hence, both are true in Killing Commendatore. To be sure, there is also a consistent fragment in which (10c) is true and (10a) is neither true nor false. So, on this view, (10a) is both true and not true in Killing Commendatore, but not false. As Lewis (1983, 277) says, on the method of union, “What’s explicit will not get lost, for presumably it will be true in its own fragment. But we lose consistency [...].”

Alternatively, if one is sympathetic to Lewis’s more conservative “method of intersection,” one can argue that since neither of (10b–c) is true in every fragment, neither is true in Killing Commendatore. Consequently, (10a) is not true in Killing Commendatore either. So, on this approach, “Even if the fiction was inconsistent, what’s true in it will still comprise a consistent theory [...].” (Lewis 1983, 277)

There may be other solutions. But note that neither of the two Lewisian approaches requires giving up MPG. Each can accept that (10a) is true in Killing Commendatore only if (10b) is. Even though presuppositions are mandatorily imported into the fictional record and mandatorily generated in the sense of MPG, we can acknowledge that there are fictions that are at least prima facie inconsistent precisely due to some presupposition being explicitly denied by the narrator.

Moreover, the observation that presuppositions must be generated is satisfied by most extant theories of truth in fiction. Here is a sample of generation principles that have been defended in the literature:

It should be clear that each of these principles conforms to MPG. In each case the condition on the right-hand side is such that if it applies to \(A_B\) it applies to B. Consider, for instance, Walton’s (1990) influential account in (13). Arguably, if one is prescribed to imagine that Susan started crying, one is prescribed to imagine that Susan was not already crying. The same applies, mutatis mutandis, to the other generation principles above.

5 Conversational implicatures in fictional discourse

In this section I turn to conversational implicatures in fictional discourse. I will argue that audiences to fictions infer conversational implicatures by relying on assumptions about cooperation on the part of the narrator. We will see that conversational implicatures can be distinguished from what I will call contextual inferences. Both kinds rely on background assumptions that are often imported by default. Yet we will see that conversational implicatures are mandatorily imported but contextual inferences are not, while neither kind is mandatorily generated.

5.1 Conversational implicatures and Gricean cooperation

Consider again the example of (1)–(2).

As we noted earlier, in ordinary, non-fictional conversation the inference from (1) to (2) is a paradigmatic instance of conversational implicature. Accordingly, it is reasonable to expect that the mechanism by which (2) is inferred from (1) by an audience to a fictional story is at least analogous to how standard conversational implicatures are inferred. As I explain below, there are good reasons to think that this is so.

Here is Grice’s “general pattern for the working out of a conversational implicature,” that is, his schematic description of the way hearers infer implicatures:

He has said that p; there is no reason to suppose that he is not observing the maxims, or at least the Cooperative Principle; he could not be doing this unless he thought that q; he knows (and knows that I know that he knows) that I can see that the supposition that he thinks that q is required; he has done nothing to stop me thinking that q; he intends me to think, or is at least willing to allow me to think, that q; and so he has implicated that q. (Grice 1989, 31)

If transposed directly to the fictional case, we would commit ourselves to a number of claims concerning what audiences believe about narrators. For instance, we would be claiming that audiences believe that the narrator knows that they know that the narrator knows that they can see that the relevant inference is needed to preserve the presumption that the narrator is observing cooperative principles. Such claims could perhaps be made plausible.Footnote 25 At the same time, it is likely that some will be wary of assumptions of this kind, in particular, for cases in which the narrator is a fictional character, like Dr. Watson or Dr. Sheppard.

There is a more neutral way of explaining inferences like the one from (1) to (2). Even when the narrator is a fictional character, it is plausible to think that audiences usually believe the narrator is being cooperative, in the sense of observing the maxims or the Cooperative Principle (henceforth, CP).Footnote 26 Indeed, when reading a dialogue in a fictional story, audiences will often have to work out that a character conversationally implicated something to another character. Doing so arguably requires at least taking the former to conform to the maxims or the CP.

Given this, at least part of the explanation for the inference is that the audience think that seeing the narrator as wanting to convey (2) is a way of squaring the fact that she said (1) with the presumption that she is obeying the maxims or the CP. Specifically, in this case the relevant presumption is that the narrator is observing the Maxim of Relation, “Be relevant.” (Grice 1989, 27) So, the claim will be that taking the narrator to be conveying that Paul did not go to the party is a way of understanding her saying that Paul had to work as relevant to the information that everyone went to the party.

This kind of explanation likewise provides a way of understanding the inference triggered by (3).

Let us say that the relevant inference is from (18a) to (18b).

As I said earlier, this kind of inference is also made in ordinary conversations. If I tell you, “My parents called. They bought a new car,” you will most likely infer that my parents told me on the phone that they bought a new car.

Again, this inference is plausibly regarded as a relevance implicature. Understanding me as wanting to convey that my parents told me on the phone that they bought a new car is a way of seeing the information that they called as relevant to their having bought a new car. By contrast, imagine that I tell you, “My parents called. They finally figured out how to use their phone.” You will not infer that they told me that on the phone because there are other reasons why the information that they called is relevant to the information that they figured out how to use their phone.Footnote 27

Similarly, a plausible explanation for the audience’s inference of (18b) from (18a) is that they are assuming that the narrator is being cooperative, and in particular, is observing Relation. As before, for this reason, I will continue to speak of these inferences as conversational implicatures.Footnote 28 Next we will see that they moreover rely on the fictional record.

5.2 Default importation

It is clear that the information that Paul did not go to the party is relevant to the information that everyone went. But why do audiences hit on the former information, having been told that Paul had to work? The answer is that they are assuming that there is a connection between having to work and whether or not someone is going to a party. In particular, they are assuming that having to work is usually incompatible with going to parties.Footnote 29

Accordingly, I suggest that the inference from (1) to (2) relies on it being part of the fictional record that, usually, if someone has to work, they are not going to a party. Unless the audience thinks that, according to the narrator, working (usually) precludes party-going, why would they think that this is what she wants to convey? Yet in many cases this underlying information will not have been explicitly stated by the narrator, nor imported via presupposition accommodation or contextual inference. In this case it is the result of what I will call default importation.

Similarly, the inference in (18) also relies on default importation. In particular, if it is not assumed that, according to the narrator, phone calls are made in order to tell people things, or something to that effect, there is no basis for the conclusion that the narrator is obeying Relation because she is conveying (18b) by saying (18a). Yet this information is not included in the fictional record as the result of something we have been told by Dr. Sheppard, either explicitly or implicitly.

Along similar lines, it is often suggested that fictional discourse relies on the audience and narrator sharing basic assumptions.Footnote 30 For instance, Eckardt (2015), argues that

Even at the beginning of a story, reader and author/narrator share some information. Apart from speaking the same language, the author/narrator will rely on shared information about the physical laws of the world, cultural institutions and practices, social environments, and much more. (Eckardt 2015, 66)

In terms of our framework this means that audiences take a number of things to be part of the fictional record, even though they are not explicitly stated by the narrator nor imported by presupposition accommodation or inferred from explicit content.

Why are certain things imported into story content by default and others not? We should not expect that there is a uniform principle behind default importation. One candidate source for default importation concerns genre considerations of the kind Lewis (1983 [1978]) discussed for truth in fiction.Footnote 31 To take one example, we mentioned earlier (in 4.1) that A Study in Scarlet is the first appearance of Holmes to the reading public. Yet, it is plausible that when reading a Sherlock Holmes story published after A Study in Scarlet, in many cases audiences will import by default that Holmes is a pipe smoker, and several other things.

I will forego further discussion of this here and instead focus on the way inferences rely on default importation, regardless of the source of background information of this kind.

5.3 Contextual inferences and default importation

There are other inferences that audiences make that rely on the fictional record, but which arguably do not arise due to assumptions about the narrator being cooperative. Above I suggested that the information that Holmes was sitting down might be imported by way of presupposition accommodation as a result of the occurrence of (6).

Yet it might be said that the information that Holmes was sitting down is likely to be already included in the fictional record, even before the occurrence of (6), simply because it is reasonable to infer that Holmes was sitting down from the explicit information, quoted earlier, that “Sherlock Holmes had not yet finished his breakfast.” (Doyle (1981 [1887]), 23) This is undeniably true. Yet this kind of importation should be distinguished from presupposition accommodation. That Holmes was eating breakfast does not presuppose that he was sitting down.

Let us say that the inference is from (19a) to (19b).

It is a clear that audiences to fictional stories routinely make this kind of inference. Here is another one:

Inferences of this kind also occur in ordinary conversational settings. If I tell you that when I got up yesterday my room-mate was still eating breakfast, you are likely to infer that she was sitting down. If I tell you that after we had dinner last night my father lit his pipe, you are likely to infer that my father is a pipe smoker.

Such inferences rely on background assumptions. In particular, for the fictional case, the inference in (19) depends on it being part of the fictional record that people usually eat breakfast sitting down. Correspondingly, the inference in (20) relies on it being part of the fictional record that, roughly, people who light pipes are usually pipe smokers. As such, like conversational implicatures, these inferences rely on default importation. Readers of A Study in Scarlet are not told explicitly that people eat breakfast sitting down or that people who light pipes are usually pipe smokers. Nor has this been presupposed or conversationally implicated. Instead, this information is part of the fictional record by default.

Yet these cases differ from the examples of conversational implicatures discussed above. For instance, we do not need to think that the narrator wanted to convey that Holmes was sitting down in order to square the fact that he said that Holmes had not yet finished breakfast with a presumption of cooperativeness. Nor do we need to infer the Holmes is a pipe smoker in order to see how saying that Holmes rose and lit his pipe is in line with observing the maxims or the CP. Rather, we infer things like (19b) and (20b) because of default assumptions about, to borrow Eckardt’s (2015, 66) formulation, “the physical laws of the world, cultural institutions and practices, social environments, and much more.”

It might be asked why we cannot say the same about, for instance, (1)–(2). That is, the narrator said that everyone went to the party and Paul had to work, the audience assume that, according to the narrator, people who have to work do not go to parties, and so they infer that Paul did not go.Footnote 32 We should agree that there can be situations of this kind. However, for many cases we will want to explain not only that audiences infer (2) from (1) but also that they conclude that the narrator wanted to convey (2) to them by saying (1). At least this will require assuming that the audience think that the narrator could see that audiences would infer (2) and did not prevent them from doing so. Yet this is arguably tantamount to assuming that the audience think the narrator is being cooperative. If the narrator does not want to convey (2) and she can see that audiences will infer (2), she is arguably violating Grice’s (1989, 26) First Maxim of Quantity, “Make your contribution as informative as is required (for the current purposes of the exchange).” Intuitively, she has said too little.

By contrast, we do not think that Watson wanted to tell us that Holmes was sitting down by telling us that he had not finished breakfast. Correspondingly, we do not judge Watson uncooperative if he did not want to convey that Holmes was sitting down. To complain that he said too little if Holmes was eating breakfast standing up is surely too draconian.

Inferences like (19) and (20) are not conversational implicatures. As I will say, they are contextual inferences. Such inferences arise because certain information is part of the fictional record, typically as a result of default importation, but do not rely on assumptions about what the narrator wanted to convey.

This conclusion can be corroborated by considering cases in which it is later revealed that what was inferred is not true in the fiction. As we said earlier, if the audience later find out that Paul in fact did go to the party, they will clearly think that the narrator had been misleading in telling them what she did. And similarly for the example from The Murder of Roger Ackroyd. However, if we find out that Holmes was in fact eating breakfast standing up, there is no parallel sense that we have been misled. This suggests that we do not take (19b) to be part of what the narrator conveyed to us by saying (19a). Even though both kinds of inference rely on the fictional record, and typically, information that results from default importation, contextual inferences are not seen as part of what the narrator wanted to communicate.Footnote 33

We should distinguish information that is part of the fictional record because it has been conveyed by the narrator from information that is part of the fictional record even though it has not been conveyed by the narrator. Information included by default interpretation and contextual inference belongs to the second category. It is clear that audiences typically keep track of this distinction.Footnote 34

So, according to this suggestion, sometimes audiences think that p is true according to the narrator, even though it is not right to say that the narrator has communicated that p. Rather, p is imported by default because taking p to be part of what the fictional world is like according to the narrator helps make sense of what she does convey and of the story more generally. But there can also be other reasons for default importation. Things may be imported by default because they are generally assumed to be true, such as that birds fly or that cars have doors, or because they are salient to the reader.Footnote 35 Such things may be imported by default even if they are not particularly necessary for making sense of the story, or of what the narrator says.

It is instructive to compare cases of default importation with cases like that of Holmes’s nostrils. We said (in 2.1) that even if one thinks that it is true in A Study in Scarlet that Holmes has exactly two nostrils, this information need not be imported as part of the story. Audiences to A Study in Scarlet need not think that it is true according to Watson that Holmes has exactly two nostrils. To be sure, they might do so, but there is no sense that cases in which they do not are deviant or outlandish.

This illustrates that something may be generated without being imported (even by default). By contrast, the cases of contextual inference just described illustrate that something may be imported even though it is not conveyed by the narrator. Moreover, as we will see below, such information may not be generated.

5.4 Inferences and importation

Like presuppositions, conversational implicatures in fictional discourse are mandatorily imported. In ordinary conversation hearers can reject conversational implicatures, as illustrated by (21).

In this case B recognizes that A wants to convey that p but prevents p from becoming common ground. By contrast, audiences to fictional stories have no such option but must include conversational implicatures in the fictional record. (As before, we acknowledge that there can be unusual cases in which a conversational implicature is not recognized, just as there can be such cases for ordinary conversation.)

To be sure, in stories like The Murder of Roger Ackroyd we later find out that certain conversational implicatures are false in the fiction. It is not true in The Murder of Roger Ackroyd that Parker said on the phone to Dr. Sheppard that Ackroyd had been murdered. But even so, we recognize that Dr. Sheppard implicated that he did. Even when we realize that the implicature is false in the fiction, we will still take it to be part of what we were told. It is a central part of the effect of such stories that we can be expected to do so.

In cases of this kind the realization that the relevant information is false in the fiction is also the result of something we are told by the narrator. After all, the whole of The Murder of Roger Ackroyd is narrated by Dr. Sheppard, and so we only find out that what was implicated earlier is false through other things that he tells us. Schematically, these are cases in which the narrator conversationally implies that p and then later explicitly says (or conveys in some other way) that not-p.

As we saw earlier (in 4.3) since we have understood fictional records to be sets of propositions, there is nothing to prevent us from agreeing that, in such cases, both p and not-p are part of the fictional record. Indeed, there is a sense that we have both been told that p and that not-p by the narrator, even though we recognize that only one of these is true in the fiction. Alternatively, it might be said that once we find out that Parker did not say on the phone that Ackroyd had been murdered, we remove this information from the fictional record. That is, we no longer take that to be true according to Dr. Sheppard. I will not adjudicate this here. I take it to be an advantage of the present account that it is compatible with either option.

Contextual inferences differ from conversational implicatures in not being mandatorily imported. For instance, when told that Holmes had not yet finished breakfast, there is no sense in which the audience is compelled to include in the fictional record that he was sitting down. To be sure, since it is later presupposed that he was sitting down, at least at that point, this will be mandatorily imported if it is not already part of the fictional record as the result of contextual inference.

5.5 Inferences and generation

We have already seen that conversational implicatures are not mandatorily generated. The implicature triggered by (3) is false in The Murder of Roger Ackroyd. Correspondingly, contextual inferences are not mandatorily generated. It might be true in some version of A Study in Scarlet that Holmes had not yet finished breakfast but false that he was sitting down. More generally, if B is a conversational implicature or contextual inference inferred from A, B may be false in a fiction, even if A is true in the fiction.

This contrasts with presuppositions. As we have seen, presuppositions in fictional discourse are mandatorily generated. The reason conversational implicatures and contextual inferences are not is that, unlike presuppositions, these inferences are not entailments. Instead, the familiar cancelability of conversational implicatures stems from the fact that conversational implicatures may be false even if the content that triggered them is true. The same holds for contextual inferences.

In other words, certain kinds of information are both mandatorily imported and mandatorily generated (presuppositions) while other kinds are mandatorily imported but not mandatorily generated (conversational implicatures), and other kinds again are neither mandatorily imported nor mandatorily generated (contextual inferences).

6 Conclusion

Importation, the process of expanding fictional records beyond what the narrator makes explicit, is distinct from generation, the mechanism that determines what is true in a fiction. Audiences distinguish the fictional record from what is fictionally true. A fictional record comprises what the audience thinks is true according to the narrator. This includes not only what has explicitly been said by the narrator, but also what has been imported.

Fictional records play the dual role of common grounds in acting both as storage and support for the narrator’s discourse. Importation operates according to principles that likewise govern the way we understand each other in ordinary conversation. These include presupposition accommodation, conversational implicature, and contextual inference. In turn, some information is included in fictional records as the result of default importation.

While both presuppositions and conversational implicatures must be added to the record, they differ in how they affect fictional truth. Since the fictional record is distinct from fictional truth, no information that is added to the record is thereby true in the fiction. Nevertheless, presuppositions constrain fictional truth in accordance with their general function as constraints on truth-values. Neither conversational implicatures nor contextual inferences do so.

Notes

The term “fictional record” was suggested to my by Nils Franzén.

Example adapted from Davis (2010).

Here, as elsewhere, I use “part of the story” to mean included in the fictional record.

This kind of example was made prominent by Bach (1994).

See Potts (2005, sec. 2.4) for an overview.

For example, as defined by Schoubye and Stokke (2016, 9), Stokke (2018, sec. 4.8), an answer to “Did Susan start crying?” is the union of a non-empty proper subset of the partition \(\{\{w:\) Susan started crying in \(w\}\), \(\{w:\) Susan did not start crying in \(w\}\}\). Since the set of worlds in which Susan was not crying before is not a proper subset of this partition, it is not an answer to “Did Susan start crying?”.

Zucchi (in press) proposes a theory of truth in fiction based on a formal semantics for an “according to” operator. There are similarities between this proposal and the one I am developing. Yet Zucchi’s framework is designed as a theory of generation, not importation.

This does not rule out views such as that of Currie (1990) according to which what is true in a fiction is delineated as the beliefs of a fictional author (distinct from explicit narrators).

Thanks to an anonymous reviewer for pressing this point.

Accordingly, if one thinks that fictional truth is generated on the basis of what the narrator conveys, perhaps in conjunction with other factors, one can appeal to such a notion of objective fictional records in order to ensure that fictional truth is not rendered relative to audiences, or readings.

This was first proposed by Karttunen (1974).

On presupposition accommodation in this framework, see von Fintel (2008).

More precisely, at least some kinds of possessive constructions are at least often thought to be definite DPs, and accordingly to impose familiarity presuppositions requiring the availability of salient, previously introduced discourse referent, along the lines of Heim (1982). For discussion of this, see Barker (1995, 2011). I allow myself to think of the familiarity requirement as represented by (7). While it is true that if (7) has been accepted earlier in the discourse, the familiarity requirement imposed by (6) will ceteris paribus be satisfied, there are of course many other ways in which it might be met.

As evidence, note that (i)–(ii) convey that John was sitting down, while (iii)–(iv) have readings that do not.

-

(i)

John didn’t rise/get up.

-

(ii)

Did John rise/get up?

-

(iii)

Lisa thinks John rose/got up.

-

(iv)

If John rose/got up, he probably went downstairs.

-

(i)

Compare so-called “conversationally-triggered presuppositions,” as discussed by, e.g., Potts (2005, 23–24), which arguably may be false even if the content that triggered them is true. This phenomenon is similar to what Stalnaker (1999 [1970]) called “pragmatic presuppositions.” I screen off such cases here and focus on the standard, or “conventional” (Potts 2005), presuppositions, as exemplified by start and the possessives discussed in the paper.

Thanks to an editor for Linguistics and Philosophy for pressing this point.

Lewis (1982, 102) suggested that corpora may be inconsistent.

Gendler (2000, 75–76) suggests that audiences and narrators share some complex assumptions of this kind.

See Franzén (in press) for a corresponding suggestion. Perhaps some will want to say that the audiences interpret the text as if the narrator were cooperative, rather than saying that the audience believe that the narrator is cooperative. Or there might be other preferred formulations. None of my main points turn on these choices.

I owe this point to Matt Mandelkern.

Similarly, see Davis (2010, sect. 6).

Similarly, Gauker (2001) has argued that all Gricean conversational implicatures can be explained as “situated inferences,” that is, “the hearer draws an inference from what the speaker literally says and the external situation; there is no need to suppose that the hearer contemplates whether the speaker had those propositions in mind” (2001, 164).

It can be argued that if Holmes is not a pipe smoker, (20a) is misleading. If so, the reason is most likely that the possessive his pipe in this case is a relation between Holmes and the pipe beyond mere ownership, or the like. Hence, this case may have a different status. If so, (19) still serves as an example of a contextual inference.

Similarly, it is often noted that, in ordinary conversation, the common ground includes information about which utterances have been made. See e.g. Stalnaker (1999 [1978], 2002), Lepore and Stone (2015, ch. 14).

Thanks to an editor for Linguistics and Philosophy for this suggestion.

References

Bach, K. (1994). Conversational impliciture. Mind and Language, 9, 124–162.

Badura, C., & Berto, F. (2018). Truth in fiction, impossible worlds, and belief revision. Australasian Journal of Philosophy, 97, 178–193.

Barker, C. (1995). Possessive descriptions. Stanford, CA: CSLI Publications.

Barker, C. (2011). Possessives and relational nouns. In C. Maienborn, K. von Heusinger, & P. Portner (Eds.), Semantics: An international handbook of natural language meaning (Vol. 2, pp. 1109–1130). Berlin: de Gruyter.

Bonomi, A., & Zucchi, S. (2003). A pragmatic framework for truth in fiction. Dialectica, 57(2), 103–120.

Borg, E. (2004). Minimal semantics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Byrne, A. (1993). Truth in fiction: The story continued. Australasian Journal of Philosophy, 71, 24–35.

Cappelen, H., & Lepore, E. (2004). Insensitive semantics—A defense of semantic minimalism and speech act pluralism. Oxford: Blackwell.

Carston, R. (2002). Thoughts and utterances. Oxford: Blackwell.

Christie, A. (2011 [1926]). The murder of Roger Ackroyd. New York: William Morrow.

Currie, G. (1990). The nature of fiction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Currie, G. (2010). Narratives and narrators: A philosophy of stories. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Davies, D. (1996). Fictional truth and fictional authors. British Journal of Aesthetics, 36(1), 43–55.

Davies, D. (2015). Fictive utterance and the fictionality of narratives and works. British Journal of Aesthetics, 55(1), 39–55.

Davis, W. (2010). Implicature. In E. N. Zalta (Ed.), The Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy (Winter 2010 edition), https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2010/entries/implicature/.

Doyle, A. (1981 [1887]). A study in scarlet. In The Penguin complete Sherlock Holmes (pp. 15–87). London: Penguin.

Eckardt, R. (2015). The semantics of free indirect discourse: How texts allow us to mindread and eavesdrop. Leiden: Brill.

Franzén, N. (in press). Truth in fiction: In defence of the reality principle. In E. Maier & A. Stokke (Eds.), The language of fiction. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Friend, S. (2017). The real foundation of fictional worlds. Australasian Journal of Philosophy, 95(1), 29–42.

Gauker, C. (2001). Situated inference versus conversational implicatures. Noûs, 35(2), 163–189.

Gendler, T. S. (2000). The puzzle of imaginative resistance. Journal of Philosophy, 97(2), 55–81.

Grice, H. (1989). Studies in the way of words. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Heim, I. (1982). The semantics of definite and indefinite noun phrases in English. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Massachusetts at Amherst. Published by Garland, 1988.

Karttunen, L. (1974). Presupposition and linguistic context. Theoretical Linguistics, 1, 181–194.

Lepore, E., & Stone, M. (2015). Imagination and convention: Distinguishing grammar and inference in language. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lewis, D. (1982). Logic for equivocators. Noûs, 16, 431–414.

Lewis, D. (1983). Postscript to “Truth in fiction”. In Philosophical papers (Vol. 1, pp. 276–280). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lewis, D. (1983 [1978]). Truth in fiction. In Philosophical papers (Vol. 1, pp. 261–280). Oxford: Oxford University Press

Maier, E., & Semeijn, M. (in press). Extracting fictional truth from unreliable sources. In E. Maier & A. Stokke (Eds.), The language of fiction. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Murakami, H. (2018). Killing commendatore. London: Harvill Secker.

Phillips, J. F. (1999). Truth and inference in fiction. Philosophical Studies, 94(3), 273–293.

Potts, C. (2005). The logic of conventional implicatures. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Recanati, F. (1993). Direct reference—From language to thought. Oxford: Blackwell.

Recanati, F. (2004). Literal meaning. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Recanati, F. (2010). Truth-conditional pragmatics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Roberts, C. (2012). Information structure in discourse: Towards an integrated formal theory of pragmatics. Semantics & Pragmatics, 5, 1–69.

Sainsbury, M. (2010). Fiction and fictionalism. London: Routledge.

Sainsbury, M. (2014). Fictional worlds and fiction operators. In M. García-Carpintero & G. Martí (Eds.), Empty representations (pp. 277–289). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Saul, J. (2002). Speaker meaning, what is said, and what is implied. Noûs, 36(2), 228–248.

Saul, J. (2012). Lying, misleading, and what is said: An exploration in philosophy of language and in ethics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Schoubye, A., & Stokke, A. (2016). What is said? Noûs, 50(4), 759–793.

Stalnaker, R. (1999 [1970]). Pragmatics. In Context and content (pp. 31–46). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Stalnaker, R. (1999 [1978]). Assertion. In Context and content (pp. 78–95). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Stalnaker, R. (1999 [1988]). Belief attribution and context. In Context and content (pp. 150–166). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Stalnaker, R. (1999 [1998]). On the representation of context. In Context and content (pp. 96–114). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Stalnaker, R. (2002). Common ground. Linguistics and Philosophy, 25, 701–721.

Stalnaker, R. (2014). Context. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Stanley, J. (2007 [2000]). Context and logical form. In Language in context—Selected essays (pp. 30–68). Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Stock, K. (2017). Only imagine: Fiction, interpretation, and imagination. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Stokke, A. (2018). Lying and insincerity. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Stokke, A. (2020). Fictional names and individual concepts. Synthese. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-020-02550-1.

von Fintel, K. (2008). What is presupposition accommodation, again? Philosophical Perspectives, 22, 137–170.

Walton, K. (1990). Mimesis as make-believe. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Walton, K. (2013). Fictionality and imagination reconsidered. In C. Barbero, M. Ferraris, & A. Voltolini (Eds.), From fictionalism to realism (pp. 9–26). Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars.

Woodward, R. (2011). Truth in fiction. Philosophy Compass, 6(3), 158–167.

Zucchi, S. (in press). On the generation of content. In E. Maier & A. Stokke (Eds.), The language of fiction. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Funding

Open Access funding provided by Uppsala University

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Earlier versions of this paper were presented at Gothenburg University, The Iceland Meaning Workshop, Skálholt, Iceland, and the University of Groningen. I am grateful to the audiences and commentators on all those occasions for very valuable feedback. Thanks in particular to Brian Ball, David Davies, Emar Maier, Karl Bergman, Matt Mandelkern, Merel Semeijn, and Nils Franzén for discussion. I am also indebted to two reviewers and an editor for Linguistics and Philosophy for very useful comments and suggestions.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Stokke, A. Fiction and importation. Linguist and Philos 45, 65–89 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10988-020-09321-8

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10988-020-09321-8