Introduction

Coming in the wake of a recent flowering of studies on Performance Art in Italy (Gallo Reference Gallo2014; Fontana, Frangione and Rossini Reference Fontana, Frangione and Rossini2015; Sciami ricerche 2020), this paper focuses on the work of several Italian artists who chose to explore issues of affection and intimacy. Giuseppe Chiari and Ketty La Rocca concentrate on relationships between couples, while Federica Marangoni, Michele Sambin and Anna Oberto touch on specifically intimate themes to create an emotional contact or interaction with spectators.

Within the varied and wide-ranging Italian panorama of visual artists who engage in performative practices – still to be thoroughly investigated – critics have highlighted prevalent references to mythology, history, art and literature, alongside phenomenological intentions, not infrequently related to the inner or deeper self, as with the artists gravitating around the Arte Povera movement (Bätzner, Disch, Meyer-Stoll and Pero Reference Bätzner, Disch, Meyer-Stoll and Pero2019). There is also a broad spectrum of research in sound poetry, mostly exploring the potential of the voice, in an effort to strengthen links between verbal and body language (Zanchetti Reference Zanchetti, Colombo, Giuranna and Sem2014).

In the following pages we will investigate a number of actions executed outside the artistic currents mentioned above and centred instead on interpersonal relationships, which aimed to develop feelings of intimacy with the public, either at first hand or by staging an affectionate or personal relationship between the artist and a collaborator. These case studies were far from infrequent, a fact emphasised throughout the paper, representative as they were of a new artistic sensibility.

Such a specifically ‘intimate’ approach can probably be traced back to a lot of misgivings surrounding the formalism that had come to characterise certain neo-avant-garde attitudes, and the covert spread and then gradual surfacing of feminist viewpoints, with the private sphere, relationships between couples, and affective relations in general taking centre stage as specific features in the life and the individual and collective identity of women. Until the early 1970s these issues had only been marginal, especially in relation to research into the body, which, as already mentioned, was based primarily on a phenomenological approach focusing on the individual in itself. Moreover, a greater attachment to sentimental themes can be observed in the world of Pop Art, with its focus on mass culture and its revisitation or lampooning of conventional literary motifs, myths and cultural references and their trite romantic clichés – as in the case of Visual Poetry, for example – through an attitude defined as ‘ante litteram deconstructionism’ (Trasforini Reference Trasforini, Iamurri and Spinazzé2001).

In the context of feminist practice and thought in Italy, and faced with a multiplicity of opinions expressed by artists in the debate surrounding ‘female specificity’ and related initiatives – as precociously highlighted by Anne-Marie Sauzeau-Boetti (Reference Sauzeau-Boetti1976) – the women's movement nevertheless helped spread a new sensibility that revived a broad range of themes, situations and relationships associated with the private sphere. Footnote 1 This complex interweaving of feminism and the visual arts is exemplified by of Carla Lonzi, whose feminist militancy led to a litigious clash and rupture with the world of art coinciding with her professional activity (Zapperi Reference Zapperi2017).

However, it was precisely the practice of self-consciousness by the feminist and separatist groups that turned the spotlight back onto the role played by dialogical relationships in the construction of the individual: individuals recognise themselves in others, sharing common experiences and conditions, beyond individual extraneousness and differences of class and age. In this regard, it has recently been noted that his encounter with several feminist artists, between 1970 and 1973, inspired substantial changes in the structure of Allan Kaprow's happenings (Goubre Reference Goubre, Cuir and Mangion2013), while several American female artists translated and transferred into their work certain ideas and forms of feminist self-consciousness (Grobe Reference Grobe2017). Something similar seems to have taken place in Italy as well, as we think the investigated cases show, in the new artistic languages embodied in and particularly receptive to current events, such as performances.

In the wake of the economic boom and the student revolts, the women's movement also took shape in Italy in the early 1970s, voicing demands on a range of issues, from new citizenship rights to a shift in how women were perceived, as independent and different from men, with their own professional, interpersonal and cultural specificities. Throughout the decade, in addition to several important victories such as divorce, the reform of family law and abortion, feminist groups, collectives, and the movement in general advocated the recognition of housework and care work and conscious motherhood. They called for new social and educational models, asking for more attention to be paid to women's health issues and social services, while also developing a radical critique of the dominant cultural values produced by a unilaterally male-dominated historiography identifiable with patriarchy (Ergas Reference Ergas, Duby and Perrot1992). This inevitably led to the questioning of traditional family hierarchies, sexual behaviour, community spaces, verbal and non-verbal languages. In Italy, as mentioned above, female artists adopted diverse attitudes toward the feminist movement, and, while substantially adhering to the principles of gender equality, they did not always agree on the more contentious issues such as separatism, or the presumed ‘specificity’ of women. The aim of this paper, therefore, is to throw light on the use of some of the rallying cries of the women's movement, including the famous slogan the personal is political, among artists of both sexes engaged in forging an original approach to performance practices (Chadwick Reference Chadwick2007).

Another aspect explored in this paper is the relationship that developed between artists and technological mediation, as one of the main channels for accessing performance artworks. The artists considered here focused on direct observation and on the viewers’ identification with a performance situation and rarely produced video or photographic media to reach a wider audience and to ensure the survival of their (art)work beyond the here and now of the performance, unlike in the international context (Bishop Reference Bishop2015). Generally speaking, no one in Italy gave the same attention found, for example, in the visual records made by Gina Pane who, not accidentally, was also the partner of her favourite (female) photographer. In fact, still photos – as opposed to moving images – freeze an instant in time, creating an unequivocal iconographic précis of a situation; videotapes, instead, can more fully preserve the narrative process as it unfolds, with its duration, sounds, and so on. Paradoxically, however, photography ensures greater visibility, penalising those artists who preferred the more complete and more engaging medium of videotape, which, over time, has proved difficult to access and preserve and is therefore confined to a more limited circulation (Jones and Heathfield Reference Jones and Heathfield2012; Delpeux Reference Delpeux2010).

Overcoming the conventions of language in search of authenticity

The first artist we will focus on is Giuseppe Chiari (1926–2007), composer, musician and visual artist, engaged in a forward-looking refoundation of the very idea of music and musical education. He started with a critique of the Western classical tradition, and became interested in the work of John Cage, seeking inspiration from conventional instruments, and from a new perception of ‘aleatoric’ music (in which some elements are left to chance), eventually imagining music as coinciding with sound in general, which can therefore potentially be generated by any means and in any situation. Of equal importance to Chiari were his joining the Fluxus galaxy – one of very few Italians to do so – which advocated a radical concept of individual and collective freedom, including with regard to different forms of artistic expression, and his adoption of Conceptual Art, from which Chiari seemed to absorb a renewed faith in the word and the dialogical dimension.

Conceived in 1968, Concerto per donna (Concerto for Woman) is an unusual Cage-inspired composition featuring a sonority which, rather than identifying with any Western musical tradition, consists of ‘gentle but varied noises obtained by blowing into a woman's hair’ (Chiari Reference Chiari and Vergine1974, 77). In spite of the title, deliberately couched in terms of the very musical tradition that Chiari calls into question, the musician produces sounds by moving and caressing the hair of a woman with his hands. Originally performed several times in public, Concerto per donna had a repeat performance in 1975 – at the Artisti e videotape workshop organised by Maria Gloria Bicocchi at the Archivio Storico delle Arti Contemporanee (ASAC) of the Venice Biennale – the video recording of which features the sounds recorded by the microphone and produced by Chiari while running his fingers through a woman's hair in the midst of a silent audience.Footnote 2

Although the identity of the female figures involved is not revealed – information that would, perhaps, shed light on the origins of the work – this tribute to femininity is not an isolated case in Chiari's production: there are photographs documenting Don't trade here, performed in Berlin in 1968 (probably on 10 February), in which, however, the exploration of sounds involved a young woman's mouth (Fig. 1). Although to a certain extent rather less poetic than Concerto per donna, and perhaps more overtly erotic, it is interesting to note that Chiari generally prefers female subjects to explore the sonorities of the human body, when he is not using his own.

Figure 1. Giuseppe Chiari, Don't trade here, 1968, Berlin (Collection Gianni and Giuseppe Garrera).

This context also features another very interesting, though little known, piece called Don't trade here. Mamma, performed during the acclaimed Contemporanea exhibition (Corà Reference Corà2000, 148), in the underground car park of the Villa Borghese in Rome on 29 November 1973. Almost two hours long, it consists of Chiari repeating the word ‘mamma’ with a different rhythm and tone of voice and using an amplification system, probably because of the huge cavernous space, certainly an unusual venue for such a celebrated event and definitely unsuitable for staging singing performances, especially if you're looking to create an intimate atmosphere. Of particular interest, in this case, is the fact that Chiari used his voice to utter the sounds of a typically childish word, in that fuzzy area between adult speech and baby language, featuring some analogies with the condition of inferiority staged by Ketty La Rocca in Verbigerazione, which we will talk about shortly.

Don't trade here. Mamma is one of a series of female references in Chiari's work, interpreted as ‘maternal’ themes by Tommaso Trini – especially since the publication of Chiari's book Musica madre (also in Reference Chiari1973) – or as a subversion of the customary cultural hierarchies of the hegemonic canon and tradition of the West (Trini Reference Trini1974). In other words, according to Trini, Chiari's musical heterodoxy aims to establish a ‘matrilineal’ genealogy, in opposition to the formal tradition identified with paternal authority, so to speak. In fact, the Florentine composer's research aims to expand the borders of music, breaking through the conceptual barriers raised by academies, canons and tradition. For Chiari, everything is music; not just sounds, but graphic signs or abstract concepts can be musical too.

The three pieces mentioned here, however, also allow us to move our discussion further. Both Concerto per donna and the photos of Chiari at grips with the mouth of a girl – which can be traced back to a version of Don't trade here, a not-so-well-documented piece, as stated above – reveal a more conventional approach to femininity compared to that of Reference Chiari1973. In the first two cases, in fact, Chiari established a rather intimate relationship with the female figure, all too naturally suggesting the well-known similarity between the shape of some stringed instruments and the female body, as well as the physical relationship generally established between the musician and the musical instrument. The explicit erotic implications are viewed within a rather traditional dialectic between the sexes, in which the woman occupies a passive and silent role, like the instrument, until the man/musician creates sounds by playing (with) her. While Chiari's work often makes use of the body, not infrequently his own, in Concerto per donna there is something more, a clear representation of a loving gesture, given that hair is a female attribute with an undoubtedly seductive potential. In this case, music becomes the (by-)product of an intimate gesture between a man and a woman, suggestive of a harmonious relationship of a sentimental and/or sexual nature. While Don't trade here calls to mind the biblical ‘cleansing of the temple’, Don't trade here. Mamma seems more like a tribute to the mother figure, to the privileged role a mother plays in the linguistic development of her child, through the performance of sounds linked to the common and familiar name of ‘mother’.

Forms of childish gibberish also appear in the work of Ketty La Rocca (1938–76), who briefly joined the Florence-based Gruppo 70, which Chiari also worked with at the beginning. The activity of Gruppo 70 was primarily aimed at deconstructing the language of advertising, films and narrative, emphasising the underlying dynamics of power and persuasion, but also bending it towards nonsense, paradox and parody (Pieri and Patti Reference Pieri and Patti2017; Pieri Reference Pieri2019). It is precisely this internal verbal-visual research that caused La Rocca to distrust verbal language, a distrust that can be found in her entire production, even after she abandoned Gruppo 70 and Poesia Visiva (Visual Poetry) at the end of the 1960s. In the new decade, in fact, La Rocca focused, instead, on the use of photography, in connection with handwriting and drawing, on videotape and on actions, with a less explicit probing than the verbal-visual collages of several years earlier, but more intimate and conceptual. In her actions, above all, alongside the linguistic component, she uses her hands to make composed and measured gestures, which, for the artist, seem to convey the authenticity of intersubjective communication.

In the language of gestures there is a wealth of mythical, ritual and fantastic elements that represent the heritage of humankind […] man in the literate society has lost the sense and value of gestures […] while in tribal communities, in primitive societies, which are not yet literate, communication is enhanced by an ‘extent’ of bodily participation, which not only supports the message but has an emotional and expressive content of its own (La Rocca Reference La Rocca and Saccà1972).

These anthropological roots are the key that La Rocca used to rediscover the language of the body, like other artists in the same period. Her actions are little documented and only a few of them have recently made their way into the artist's catalogue, like the one performed only once at the exhibition La ricerca estetica dal 1960 al 1970 (Aesthetic Research from 1960 to 1970), curated by Filiberto Menna, as the third stage of the 10th Quadriennale d'Arte di Roma, at the Palazzo delle Esposizioni in 1973. There are no photographs of the event but there is an exceptional video recording by Francesco Carlo Crispolti as part of the so-called Videogiornali (video journals) of the event (Gallo Reference Gallo2018).

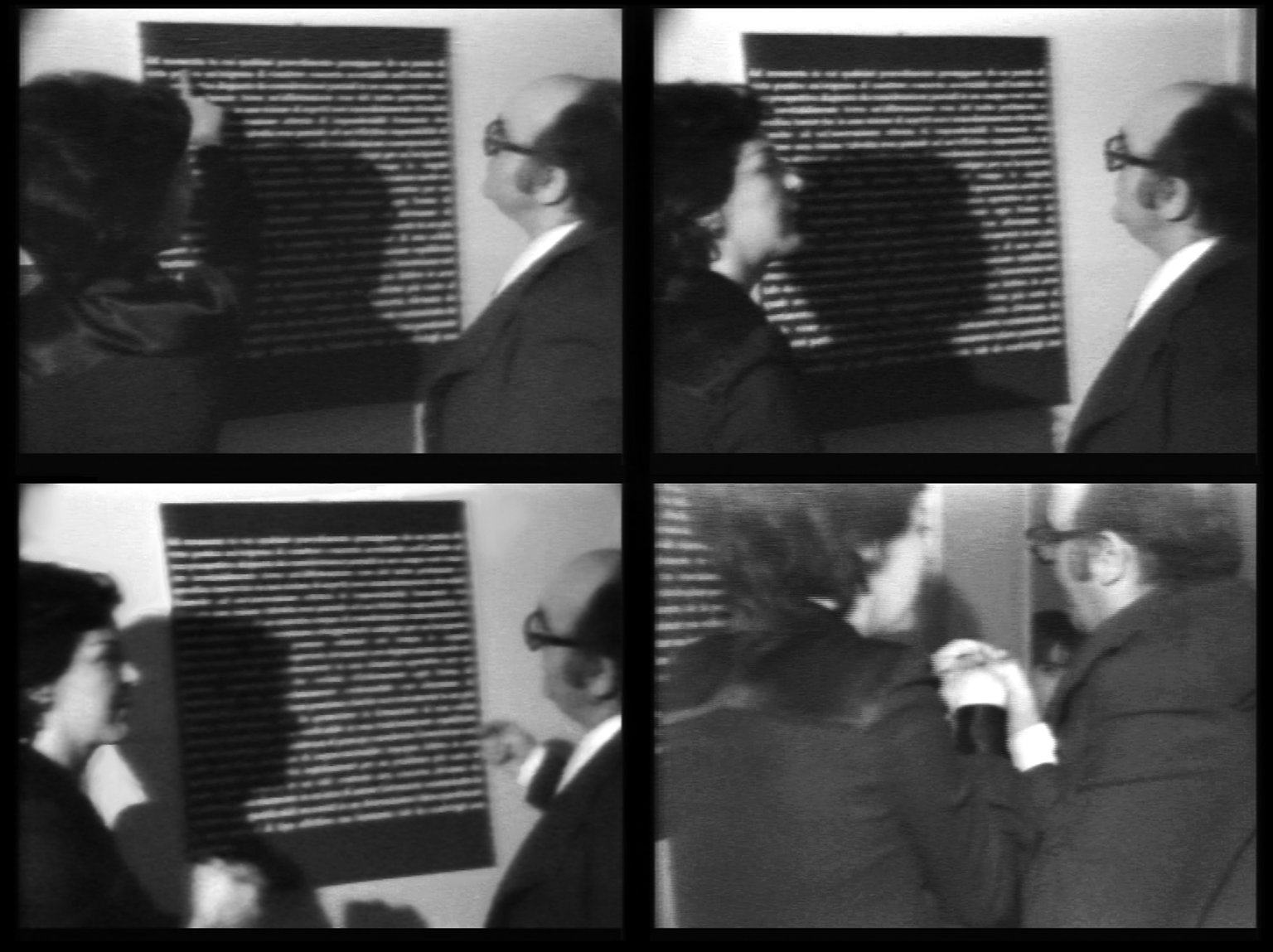

Created in collaboration with Giordano Falzoni, a versatile painter, writer and later actor, and performed both for the public (on 27 May 1973) and for the camera alone, the action is entitled Verbigerazione (Fig. 2), with reference to verbigeration, a verbal communication disorder of psychiatric origin, and is the result of the convergence of La Rocca's desire to step back from the limelight and Falzoni's project called ‘infiltrating the artist’ at the Rome exhibition.

Figure 2. Ketty La Rocca, Verbigerazione, 1973, with Giordano Falzoni. Rome, Palazzo delle Esposizioni. Stills from videotape (courtesy

Fondazione La Quadriennale di Roma).

This collaboration does not imply co-authorship: La Rocca remains the ‘mother’ of the work, even though she carves out a ‘back-seat’ role for herself, or rather a supporting role to Falzoni's verbal performance, consisting in the sometimes emphatic, sometimes uncertain reading of the artist's text Dal momento in cui (From the Moment When). Falzoni, in fact, reads like a child struggling to learn how to read, he stumbles and needs a guide, the help of an adult, in this case La Rocca. The very nature of the text is such that it does not allow the transmission of content or the sharing of any message between the two, being a succession of nonsense, empty interjections and turns of phrase. The two artists, in fact, seal their complicity hand-in-hand, a gesture of solidarity that crowns a common enterprise, at which point the video operator artfully stops filming, probably after several off-camera rehearsal sessions, and the result of a particular consonance between Francesco Carlo Crispolti and La Rocca's artistic research.

The impossibility of full verbal communication, the representation of the miscarriage of language and of its principal expressive and social functions specifically draw attention to the staging of negation that Anne-Marie Sauzeau-Boetti would soon identify as the main characteristic of women's art (Sauzeau-Boetti Reference Sauzeau-Boetti1976).

Generally speaking, La Rocca understands the man-woman relationship in a problematic, even conflictual, way, a fact that emerges, for example, from several sequences of the well-known videotape Appendice per una supplica (Appendix for a Supplication); furthermore, in Verbigerazione the apparent complicity with the male pole is based on a basic level of understanding since verbal language is ineffective and – in this case – is not replaced by any particularly meaningful gestural communication. It may therefore be useful to recall the artist's project for a game called In principio erat verbum (In the Beginning was the Word), dating from 1970–72, which was never actually realised but whose instructions clearly reveal La Rocca's complex and articulated thoughts about the limits of verbal language and the potential of body language, in particular of the face and hands (Gallo and Perna Reference Gallo and Perna2018), as can also be seen in the photographic book In principio erat (La Rocca Reference La Rocca1971). In the latter, verbal language is stripped of meaning, or reduced to nursery rhyme refrains, thus emptying words of their capacity to communicate anything, as in Verbigerazione – a destructive attitude that persists in the series of Riduzioni (Reductions), as well as in her best-known action, Le mie parole, e tu (My Words, and You), produced in three different contexts during 1975.

The action In principio erat verbum is based on gestural communication as a total substitute for words, given that the interaction between the artist – at the centre of the performance – and the individual participants who alternate in front of her, is executed solely through gestures of the face and the hands. It is only in Verbigerazione, however, that this interaction clearly takes on an affective value, of concrete solidarity, in the face of the collapse of language, which is all the more interesting given that La Rocca and Falzoni knew each other, and that they are probably re-enacting, in this case, a sort of positive – rather than conflictual – dynamic between genders, as opposed to Appendice per una supplica. In the latter case the references to the male-female relationship are subtly referred to but quite clear, while in Verbigerazione the obvious age gap between the two and the male condition of difficulty or minority primarily refers to a child learning to read or an elderly man losing the capacity to speak properly.

In later years, La Rocca no longer mentioned either the action Verbigerazione or the videotape recording on which it survived. We do know that she would have liked to record other videos – especially with art/tapes/22, in Florence – since she exhibited Appendice per una supplica, her first performance with this medium, as a videotape and not as a recording of an action, several times. In fact, La Rocca was generally uninterested in recording her work, probably due to the ‘collector's attitude’ many body artists had towards photographs and recordings. On this subject, the artist notes that although her actions were seen by few people, photos would not replace her work:

The recording of an action by photography, although interesting from another angle, is something entirely different: it's information, the action itself is misrepresented, it can't escape being mystified and becomes subject to the rules that govern information. The inauthentic then manages both the action and its photographic record (La Rocca Reference La Rocca and Saccà1975).

Photography, films or videos, therefore, are branded as ‘inauthentic’ and – writes La Rocca – they tend to widen rather than narrow the gap between audience and artwork, which is probably one of the reasons why La Rocca, like many others, airbrushes the photographs to restore their ‘authenticity’, in other words their power of meaning. This prejudicial approach towards recording actions can be better understood if one keeps in mind, for example, the freedom with which various artists at the time – not just Italians – used documentary photography. While single iconic shots were preferred by the Rome-based artists, as in the case of Jannis Kounellis, Gino De Dominicis or Luigi Ontani, various artists gravitating around the Arte Povera movement liked to blur the boundaries between action and photography, as in the case of Rovesciare gli occhi by Giuseppe Penone.Footnote 3 Chiari, too – whose closeness to La Rocca has already been mentioned – at least from the 1970s onwards, appropriated the photographs of his performative actions and transformed them into self-standing works, showing an irreverent attitude towards the idea of ‘authorship’ of photographers, who are likened to a sort of assistant/collaborator in the action or even a merely mechanical instrument. For Chiari, therefore, the idea of ‘reproducibility’ has little to do with Walter Benjamin and takes on a more creative and proto-appropriationist meaning, in line with Fluxus, which professed the free circulation of ideas and works, in many ways a forerunner of the recent no-copyright philosophy.

The quest for a new relationship with the public

Undoubtedly, the new outlook opened by feminist thought played an important role for Ketty La Rocca, and probably Giuseppe Chiari as well, as mentioned above. Although La Rocca never explicitly acknowledged being part of the women's movement, she nonetheless decried gender inequality in both her writings and her art (Di Raddo Reference Di Raddo, Gallo and Perna2015). In the early 1970s, Giuseppe Chiari, as Trini noted, was intrigued by the innovative perspectives of an ideal and hypothetical matrilineal descent in the field of musical tradition, as a synonym for new hierarchies of values. These ideas gradually burgeoned throughout the decade, to the point that their effects are reflected in the attention to interpersonal and intimate contents in other authors as well. While the works mentioned here show how Chiari and La Rocca created intimacy between the artist and other people, staging – we could say – a privileged two-way relationship between a man and a woman, other artists, in order to achieve a similar sense of intimacy, addressed the public directly, seeking spontaneous interaction with them without resorting to the metaphor of the heterosexual couple. This is the case, for example, with several Italian women artists who experimented with performance introducing specific cultural content, such as Mirella Bentivoglio, Tomaso Binga (the pseudonym of Bianca Pucciarelli Menna), Lucia Marcucci, and Libera Mazzoleni, to name but a few (Scotini and Perna Reference Scotini and Perna2019).

We can also include Federica Marangoni (born 1940) and her work, consistently engaged as she was, since 1975, in actively furthering the theme of live sculpture (Conti Reference Conti2008), in particular in the series of casts of her own body entitled Il corpo ricostruito (The Reconstructed Body), which she brought into the public space like a hawker selling lace. Marangoni is best known for her urban-scale sculptures and for her prolonged video-art experimentation centred on the themes of life and the relationship with nature. In the 1970s, however, she also focused on her own figure to the extent that her self-portrait and body repeatedly appeared in her works. Her work of interest to us here, Ricomposizione e vendita della memoria (Reconstructing and Selling Memory) (1975, Fig. 3), hinges on the objectification of the female body with clear references to its commodification. This general observation, which affects advertising, mass communication and, more profoundly, relations between the sexes, is interpreted by Marangoni in an artistic context where, in her opinion, female artists were wont to accept excessively harsh trade-offs for the sake of their careers and to achieve public visibility. The polyester casts are transported inside a trunk called The Box of Life: despite the title, however, the body inside is dissected, transformed into a specimen for an anatomical theatre or a wax museum; thus, the refined sculptures, which also reveal her design skills, allude to a life cut short.

Figure 3. Federica Marangoni, Ricomposizione e vendita della memoria, 1975 (photo Fulvio Roiter, courtesy Federica Marangoni).

In Ricomposizione e vendita della memoria, by substituting a hawker's goods with casts, Marangoni designed her trunk to ‘go out into the world, […] to rediscover a dialogue with people in the marketplace, in the streets. […], in short, I took this memory of mine, placed it on my shoulders and returned to meet the old hawker's customers’ (Marangoni Reference Marangoni2019). Ricomposizione e vendita della memoria, therefore, begins with a personal memory common to her generation (a hawker selling lace) but which no longer has a modern-day equivalent, being rooted in a social context that has since disappeared, but which Marangoni tries to conjure up again by going out into the streets and meeting passers-by, rather than the select public of an art gallery, doing away with any intermediation via the dedicated ‘milieu’.

At the time, neither was Marangoni interested in recording her own work, so she used photographs of the action in a silkscreen folder in which Roberto Sanesi's text superimposes a heteronomous narrative dimension onto the work, somehow overwriting the artist's explicit intentions. In the following years, Marangoni continued her engagement with performance art for a short time, also producing videotapes: regarding this later production, however, while the references to the artist's body remain, there is no longer any quest for intimacy, but rather the staging of a self-produced violence with fire that melts the wax casts of the artist's body (1979, at the Sala Polivalente, Ferrara) or with nails, hammer and scissors that destroy or nail to the floor the metal, glass or paper butterflies of Il volo impossibile (The Impossible Flight). In the latter cases Marangoni performs strong, vindictive or self-punishing gestures on her work, which has the shape either of the artist's body or of the insect popularly identified with the female sex. Therefore, it is only in Ricomposizione e vendita della memoria that Marangoni seeks to establish a close rapport with the public of passers-by and ordinary people, rather than with contemporary art enthusiasts, while later on the gestural and material symbolism she displays can only push the observers away, keeping them at a distance – like at the theatre – rather than close to the artist, or simply watching a recording, as in the case of the videotape of her performance of The Box of Life (1979).

Private emotions

In the second half of the 1970s, however, we encounter other artists who make a show of their emotions in public, so to speak, but without any aggressive iconography. One of these is Michele Sambin (born 1951), who is also one of very few Italians who can define themselves as performers in the full sense of the word, their research being based on a strong relationship between body, music and videotape, particularly – in this decade – thanks to the video workshop at the Galleria del Cavallino in Venice. In this productive environment, Sambin explores the formal potential of the new medium, engaging in live performances that relate to the peculiarities of the medium (Lischi and Parolo Reference Lischi and Parolo2014), adopting an analytical and metalinguistic approach typical of early video art, for example, featuring a divided screen and filming the subject from different angles in dialogue with himself. Central to his few performances with an audience is Ascolto (Listening) (1976–7), performed both at the Galleria del Cavallino and at the University of Venice and captured both on video and in photographs. Sambin speaks of this work in the following terms:

I arrived in front of the audience, sat with my back to the wall, the music started and … I cried. What I was trying to convey with this action was a sense of unease, of powerlessness in the face of events. I immersed myself and the spectators in a contradictory situation. Why cry in public? The cause of my state of mind was not clear to them and I think each one of them had their own answer. Moreover, there was a very strong discord between my emotions and the music (Sambin Reference Sambin2013).

Ascolto was inspired by the political situation in Italy at the time – 1976 – plagued by violent clashes and demonstrations in the streets. The gravity of this situation stimulated the artist – who lived in Padua, an important university town with a large number of radical political groups – to give ‘voice’ to his emotions, to stage the sadness and regret that overshadowed those months. So much so, Sambin recalls, that crying in front of an audience had come to him easily, all he needed to do was concentrate on his friends who had been involved in armed clashes or even arrested. This was no allegorical performance but a sort of public confession of his state of mind.

The loudness of the rock music soundtrack would have made it impossible for the audience to actually ‘hear’ him cry, and the actual tears could only be seen by those sitting in the front row and closely observing the artist's face. In the videotape of the action, in fact, only the music can be heard, but the video recording is more effective from a visual point of view because, at a certain point, the camera zooms in on Sambin's face, thus metaphorically shortening the distance between the artist and the spectator and revealing the tears running down his face, behind the dark glasses he's wearing. This camera movement invites the viewer to establish a more intimate relationship with the artist, to tune in to his emotional state. The Ascolto videotape, therefore, is not only a recording of the eponymous performance, but a work in itself, which takes the performance to a higher level of formal wholeness, enhanced by the technical and stylistic peculiarities of the electronic device. The photographs of Ascolto, instead, provide a more instructive and explicit version of the work because Sambin himself painted the tears blue directly onto the prints (Fig. 4).

Figure 4. Michele Sambin, Ascolto, 1977, Trieste (courtesy Michele Sambin).

Another significant aspect of the work comes from Sambin's musical training: the title Ascolto suggests a dimension of sound, referring as it does to both music and words. In this case, however, the artist asks, first and foremost, for his emotional outburst, his confession, to be accepted, even though the only sound to listen to, strictly speaking, is the rock music. Prompted by musical encoding, Ascolto suggests the idea that the artist is performing a solo piece, as a singer or musician would, while the loud rock music indicates emotional strife and anger.

While the performance appears hermetic and, as such, encourages the spectators to infer the inner feelings staged by the artist from his appearance – especially the dark glasses, like those worn at funerals to conceal one's grief – and the rock music, the video recording and photographs clarify the content of the work; in this case, the technological mediation the artist employs does not serve the purpose of keeping people away and cooling down emotions, but allows a more effective formal display of the emotional content of the work, as interpreted by the linguistic capabilities of the devices.

A final example of the quest for intimacy with the public, almost at the close of the first successful season of performance art experiences in Italy, is Anna Oberto (born 1934), active in the field of visual poetry alongside Martino Oberto in the 1960s and a promoter of avant-garde events, including some specifically for women. Compared to the other artists considered so far, we are faced here with a different awareness of gender issues and how they can be depicted in the visual sphere.

Oberto is the author of a complex corpus of actions called Scritture d'amore (Writings of Love, 1979–85), consisting of ritual actions, photographs and videotapes, which, beginning with the title itself, proclaim with unprecedented eloquence their intimate and personal nature, filtered at times through literary references. The artist also defined the series as a mythical biography, that is to say an imaginary autobiography, a way of building one's own identity from a set of real and fictitious elements, in a new phase of one's life.

Regarding the themes addressed here, her most relevant work is Il rituale dei doni (The Ritual of Gifts), an action performed over the space of four days in June 1982, in Genoa. Anna Oberto moves among the public, in a dark room, where she uses a torch to illuminate – or, rather, visually highlight – several objects, including photographs, a notebook in which she writes, and so on. In the meantime, the audience listens to a pre-recorded audio tape and the artist enters and exits the room until the tape ends. Only at this point does Oberto begin to unwind a red thread among the viewers, metaphorically binding them to herself and to each other (Fig. 5), speaking to each of them a few sentences from a long text Diario in / pathos sequenza, a sentimental diary dedicated to the relationship between writing and female identity, interspersed with love letters and reflections on life as a sentimental journey.

[…] now the birth of the tale / this is the place of narration / the red thread weaves the fabric / you the protagonists) […] (alpha, the first letter of the alphabet of the sacred language / has the shape of a woman pointing to the sky and the earth / the one mirroring the other) […] we have known of your coming and we have made a carpet / out of the blood of our hearts and the gold of our eyes […] of our cheeks to meet you / so that you can walk over our eyelids) […] (I see eyes close together that stare inside me, and my eyes are lost / in them, I see my face and their faces / I see the unity reflected in the mirroring / of ourselves, through exchanging the gifts of the ritual, of our essences / The circle is closed to infinity) (Oberto Reference Oberto1993, 13a–15a).

Figure 5. Anna Oberto, Scritture d'amore. Il rituale dei doni, Genoa 1982 (photo Mario Parodi, courtesy Anna Oberto).

The text resembles a sort of stream of consciousness, which Oberto adapts to the person she is talking to. Each spectator receives special attention from her and becomes the focus of the scene for a few seconds, a typical feature of the artist's work (Solimano Reference Solimano and Solimano1993). The importance of verbal language is worth noting as it contributes, even if in a fragmentary and allusive way, with the objects to guiding the spectators in the field of personal relationships. The place in which the action takes place also contributes to the intimate atmosphere: it's the artist's home, a room called My Poetic Room. Anna Oberto physically and metaphorically opens her private space and confides to the public the events of her life, her emotions and memories, through objects and words. The domestic dimension is undoubtedly central to women's artwork, and many women artists in recent years have dedicated a certain amount of attention to it with the aim of subverting the male canon of representation of the artist at work (Winkenweder Reference Winkenweder, Jacob and Grabner2010), such as the kitchen where Marisa Merz filmed La conta (1967), the bedroom in which Giosetta Fioroni set La spia ottica (1968), or the key role assigned by Tomaso Binga to the living room in Carta da parato (1976). Il rituale dei doni, however, is also more generally connected to the search for alternative spaces to those found in mainstream art, constantly dominated by male artists: this is particularly evident in the case of Oberto who, as mentioned, was also among the first to promote exhibitions by women artists.

In Il rituale dei doni, moreover, thread as a theme is an explicit reference to the relationship of love that the artist establishes with the spectators, but – more generally – it becomes a sort of statement of poetics for an artistic pursuit under the banner of affectivity and gifting, which can also be seen, to a certain extent, in Gina Pane, although she uses an entirely different iconography. With the same symbolic meanings, threads can also be found in Maria Lai's famous collective action, Legarsi alla montagna (Tying Oneself to the Mountain), performed just one year earlier, in 1981, in the artist's home town of Ulassai, in Sardinia, where the entire community was involved by Lai in ‘tying together’ the houses in the town with different coloured ribbons, each colour corresponding to the temperature of the interpersonal relationships between the families living there. More generally, weaving is a traditionally female craft – as reaffirmed by Lai with her looms – and in the 1970s thread was used precisely in connection with writing as a reminder of an archaic, ancestral knowledge, an alternative to the logocentrism of the hegemonic (male) culture, of which women are considered – at times – the privileged repositories (Bentivoglio Reference Bentivoglio1978).

If we consider, finally, the visual recording of these actions, we find that even Anna Oberto was rather uninterested – in fact hardly any were made. The photographs of Il rituale dei doni were taken not at the artist's request but on his own initiative by Mario Parodi. Here too, later on, the shots became an independent work by Oberto after being airbrushed. For documentation purposes, however, it was only at the author's request that the artist collected and digitalised the original shots of these historical works, proving, if proof were needed, the difficulty encountered in historicising such practices.

The examples offered here provide a rather broad and diversified panorama of the interest in affective, intimate, personal issues by artists who also make use of performance. On the one hand, this can be traced back to an extension of the analytical and self-reflective practices of the neo-avant-garde, but on the other hand it can be related to the demands made by the women's movement, which at that same historical juncture advocated a new dignity in private life, affections and interpersonal relationships. This latter set of themes, however, was also reprised in several artistic currents of the 1980s, sometimes even without any acknowledgement of their female origin.

Regarding technological mediation and/or documentation, on the other hand, on top of the widespread difficulties of female (and sometimes male) artists in acknowledging its importance, also because of material contingencies and a certain lack of self-awareness, in the cases examined here there is a tendency to reutilise photographs and videotapes of artistic actions as autonomous artworks, sometimes manipulating them and giving them a new meaning, forging new creative pathways and therefore creating new works. Against this backdrop, the reluctance to disseminate their own images seems to be specific to women, in response to the pervasive reification of the female body in the context of consumerism, the media system and stardom. This consideration is also corroborated by the limited use of nudity in the artistic actions of Italian women artists in general, especially if compared to the amount of nudity observed in the international context of these studies and in relation to the reappropriation of the body and of sexuality professed by the feminist movement. This is yet another feature that runs counter to the international tide in the world of art, reaffirming a certain peculiarity of the Italian art scene, which does not easily lend itself to being pigeonholed into European and North American categories.