Abstract

Ethnic and racial disparities in educational outcomes, such as test scores, are a core issue of educational research. While the role of student and family factors in the formation of such disparities is well established, existing studies fail to draw a similarly clear picture of how teachers contribute to ethnic and racial achievement gaps. In contrast to previous studies, which focussed on the consequences of rather blatant forms of discrimination, such as in teachers’ grading practices, this study investigates rather subtle processes that might result in discrimination of ethnic and racial minority students. In particular, I address stereotypes among teachers and analyse if they induce bias in their achievement expectations for ethnic minority school beginners. Additionally, I analyse if such bias results in a self-fulfilling prophecy and contributes to ethnic achievement gaps at the end of first grade. Multilevel regressions applied to a sample of 1007 children and 64 teachers in German primary schools reveal that different teachers internalize distinct stereotypes regarding ethnic achievement gaps and the achievement-related attributes of ethnic minority students. I also find that teachers with more negative stereotypes expect lower mathematics and reading achievements for ethnic minority students at the beginning of first grade. However, although I replicate the finding that inaccurate teacher expectations result in a self-fulfilling prophecy, I find no statistically significant effects of teacher stereotypes on ethnic differences in the development of students’ reading and mathematical skills throughout first grade.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

In most Western societies, school performance varies between majority and ethnic minority students, and some minority groups perform closer to national averages than other groups (e.g., OECD 2016). Ethnic and racial achievement gaps among young school children translate into disparities in subsequent stages of the educational trajectories and eventually into disadvantageous opportunities in life among ethnic and racial minority members (Heath et al. 2008). While the role of student and family factors, such as socioeconomic status (SES) and proficiency in the language of instruction, in the formation of such disparities is well established, existing studies fail to draw a similarly clear picture of how teachers contribute to ethnic and racial achievement gaps (see Farkas 2003). Previous studies produced mixed results regarding rather blatant processes, such as discrimination in teachers’ grading practices (e.g., Bonefeld and Dickhäuser 2018; Van Ewijk 2011). At the same time, less attention has been paid to more subtle and unintended processes that might stem from teachers’ achievement expectations and their effects on teacher-student interactions.

A lack of knowledge in this regard is surprising given that experimental evidence from the U.S. (Anderson-Clark et al. 2008; Tenenbaum and Ruck 2007) and Europe (Tobisch and Dresel 2017) indicates that teachers have lower expectations for the achievements of ethnic and racial minority students than for majority students, even after controlling for the students’ abilities and skills. This evidence is potentially important for research concerning ethnic and racial educational inequality since experimental studies also showed that differences in teacher expectations can result in a self-fulfilling prophecy if the academic achievements of students adapt to the teacher expectations (Rosenthal and Jacobson 1968). Non-experimental field studies confirmed that teacher expectations vary based on students’ ethnicity and race after controlling for differences in students’ achievements (Lorenz et al. 2016; Meissel et al. 2017; Ready and Wright 2011). When considered together with the findings of other non-experimental studies that replicated the existence of self-fulfilling prophecies in real-world classrooms and schools (e.g., Gentrup et al. 2020), this evidence suggests that teacher expectations contribute to ethnic and racial disparities in education (Jussim et al. 2009b). However, to date, this assumption has only rarely been tested directly.

Examining whether teacher expectations induce subtle forms of ethnic and racial discrimination requires, in a first step, an investigation of the possible mechanisms underlying the group-specific differences in teachers’ expectations. In this regard, experimental studies point to the importance of stereotypes among the teachers, which can be applied unintentionally during impression formation (Glock 2016). Without testing such mechanisms, it remains unknown if the statistical effects of student race and ethnicity on teacher expectations are spurious due to systematic differences in the students’ skills, which were unmeasured but affected the teachers’ evaluations (Lucas 2008). In a second step, it is necessary to link ethnic and racial differences in initial teacher expectations to group differences in students’ later scholastic performance while controlling for the initial differences in students’ abilities, skills, and other factors that determine learning progress.

Aiming to meet these challenges, I use data from Germany to investigate stereotypes among primary school teachers and how those stereotypes are related to differences in the teachers’ achievement expectations for school beginners of different ethnic backgrounds. Additionally, I examine whether differential teacher stereotypes result in a self-fulfilling prophecy and hamper the development of ethnic minority students’ reading and mathematics skills throughout first grade. I rely on two measures of teacher stereotypes, including teachers’ beliefs regarding the average achievements of different ethnic groups of students and teachers’ agreement with generalizing statements regarding the achievement-related attributes of ethnic minority students.

2 Self-fulfilling prophecies in the context of ethnic and racial disparities in academic achievements

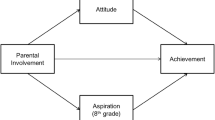

It is well established in the literature that teacher expectations can induce a self-fulfilling prophecy (for a review of the international literature, see Wang et al. 2018). This phenomenon occurs as a result of the following three basic steps: (1) initial teacher expectation inaccuracy, (2) teacher expectation mediation, and (3) subsequent effects on student learning.

Inaccuracy in teacher expectations is a central precondition for self-fulfilling prophecies to occur in the school context (Merton 1948). Inaccuracy represents incongruence between teacher expectations and those characteristics of students which—from a pedagogical perspective—are central preconditions of their learning progress (de Boer et al. 2010). Teachers can then mediate their expectations in verbal and non-verbal ways (Babad 2009) through different types of behaviour (Harris and Rosenthal 1985). For example, teacher expectation inaccuracy is related to different dimensions of teacher feedback (Gentrup et al. 2020). Finally, students can react to such differential treatment in such a manner that confirms the initial teacher expectations. As a result, students for whom teachers have inaccurately low expectations can experience lower achievement gains than students for whom expectations corresponded more closely to their initial achievement, and vice-versa (Jussim et al. 2009b). Such relationships have also been labelled teacher expectation effects (e.g., Rubie-Davies et al. 2014).

2.1 Residual effects as indicators of teacher expectation bias

Teacher expectation bias reflects teacher expectation inaccuracy based on ascribed student characteristics, such as ethnicity and race. Scholars interpret residual effects from regressions of student ethnicity and race on teacher expectations that remain after controlling for learning preconditions as manifestations of ethnic and racial teacher expectation bias (see Madon et al. 1998). This procedure is chosen because counterfactual models are inappropriate for empirically identifying discrimination since the treatment (e.g., being a minority member) cannot be randomly assigned to the study participants, as is the case for other treatments (e.g., being fluent in the language of instruction) (Lucas 2008).

However, the problem with this method is that the statistical effects of student ethnicity and race on teacher expectations might also reflect unobserved heterogeneity. That is, teachers may consider unmeasured information regarding their students that is relevant for the youths’ learning progress. In these instances, the residual effects of student race and ethnicity on teacher expectations may reflect a possibly valid prognosis rather than bias. Therefore, unobserved heterogeneity remains a possible alternative explanation for ethnic and racial teacher expectation bias. Since only an inaccurate teacher expectation can initiate a self-fulfilling prophecy, this criticism also challenges the evidence provided by the few studies that tested associations between expectation biases and group differences in students’ scholastic performances (Madon et al. 1997; van den Bergh et al. 2010).

Lucas (2008) suggests that one way of countering such critiques is to switch the focus from examining the extent of discrimination to examining the actual causes of discrimination. Translated to the research question of the present study, this approach requires, first, the consideration of social factors that initiate bias in the evaluation of minority students’ potential to succeed in school and, second, to corroborate empirically that these factors are related to statistical effects of race and ethnicity on teacher expectations.

2.2 Accounting for ethnic and racial bias in teacher expectations: the role of teacher stereotypes

Possible mechanisms underlying ethnic teacher expectation bias can be deduced from the social psychological concept of stereotypes. Stereotypes are generalized beliefs regarding the average characteristics and attributes of categories of people (Schneider 2005). Perceiving target persons based on stereotypes means that attributes that are associated with a certain category label (e.g., “ethnic minority students”) are ascribed to targets that have been identified as members of that category. Stereotypes among teachers may include generalized beliefs regarding the achievement of certain social groups of students. Such stereotypes would reflect a particular type of stereotypes, namely, those that link the group membership of students to certain levels of average group achievement. In the following, such estimates are designated as achievement stereotypes. However, teachers’ generalized beliefs must not be restricted to student achievements. Instead, teachers might also have stereotypes related to other student attributes, such as knowledge, skills, motivation, interest, and attentiveness. I refer to such stereotypes as achievement-related stereotypes.

The application of stereotypes occurs automatically in almost all daily situations (Devine 1989; Hamilton 1981). Thus, categorizing people, activating beliefs regarding the corresponding categories, and forming impressions of people based on the activated beliefs are default processes in human perception (Fiske et al. 1999). The processes of automatic categorization and generalization are particularly likely to occur when information is scarce or ambiguous and when only a few cognitive recourses are available to the perceiver (Gawronski et al. 2003). Since teaching is a multifaceted task that requires teachers to simultaneously address different aspects, such as focussing on the current interaction while considering the different requirements and needs of individual students (Hattie 2009), the availability of cognitive resources to teachers during lessons may be scarce, in general. Thus, to some extent, stereotypes might always be involved in the formation of judgements of students, even though this occurs unintentionally.

The types of stereotypes activated (ethnicity-related, gender-related, etc.) depend on the presence of detectable cues that render the group status of a person salient, foster the application of stereotypes, and hinder the processing of actual information and the integration of such information into multifaceted judgements (Fiske et al. 1999). Previous research has shown that ethnicity and race are among the most important sources of social categorization (Fiske 1998), and physical appearance is a particularly salient characteristic that causes generalizations (e.g., Zebrowitz 1996). Therefore, a student’s visible ethnic minority background might trigger the application of ethnic achievement and achievement-related stereotypes among teachers and, hence, lead to ethnic bias in their achievement expectations.

Stereotypes among teachers can reflect generalized beliefs that are shared within a society (Devine 1989). For instance, achievement and achievement-related stereotypes might be driven by media reports of the typical patterns of student achievements, such as those published and commented on regularly in the context of large-scale educational assessments (Peterson et al. 2016). This assumption is supported by the finding that teacher beliefs regarding ethnic inequalities correspond to actual patterns of ethnic disparities in educational outcomes (Wenz et al. 2016).

Existing evidence also suggests that teachers differ in how strongly their expectations are biased (de Boer et al. 2010). One reason for these disparities may be that teachers internalize different stereotypes and, therefore, perceive the size of ethnic or racial achievement gaps differently. This corresponds to the notion that stereotypes can be more or less (in) accurate (Jussim et al. 2009a). That is, the attributes associated with a certain category can deviate from the actual average attributes and behaviours of the category members, but they can also match relatively closely to the actual group averages (Hilton and von Hippel 1996). Hence, the stereotypes of some teachers may exaggerate the magnitude of ethnic or racial achievement gaps, whereas the stereotypes of other teachers may correspond more closely to actual ethnic or racial disparities in scholastic performance (Jussim et al. 1996). Consequently, ethnic and racial teacher expectation bias may be more likely to exist among teachers who perceive the educational achievements and achievement-related attributes of minority students to be more disadvantageous than among teachers who internalized more positive stereotypes.

3 The present study

The first aim of this study is to determine whether stereotypes among primary school teachers trigger ethnic bias in the achievement expectations they hold for school beginners. Second, I address the question of whether stereotypes influence students’ school achievements by inducing a self-fulfilling prophecy and, thus, contribute to ethnic inequalities in academic performances throughout the first school year.

The German school system provides a very important context for this research. In Germany, student achievement during the first four years of primary schooling is crucial for the transition of students to the different tracks of secondary schooling. Hence, teacher expectation effects could have long-term consequences on students’ educational trajectories since they might affect the first educational transition and, therefore, the educational certificates that students can eventually attain. I also focus on Germany since ethnic disparities in educational outcomes are well established in this context (e.g., Kristen and Granato 2007). Additionally, empirical evidence has revealed pronounced negative stereotypes regarding ethnic minority members in Germany (e.g., Kahraman and Knoblich 2000).

Currently, individuals of Turkish origin constitute one of the most relevant ethnic minority groups in Germany in terms of population size. Initially, immigration from Turkey resulted from recruitments of so-called “guest workers” during the 1960s and 1970s. These labour migrants mostly worked in unskilled and semiskilled jobs. Compared to their majority peers, students from Turkish families currently reach lower levels in standardized achievement tests, show lower levels of destination-language proficiency, more often attend the lower school tracks, and attain lower educational qualifications (Stanat et al. 2016, 2017).

A second important ethnic minority population in Germany has its roots in Eastern Europe, with the former Soviet Union and Poland representing the main countries of origin. This group partially consists of ethnic Germans who migrated to Germany mainly from today’s Russia, Kazakhstan, Ukraine, Poland, Rumania and the Czech Republic after the collapse of the former Soviet Union in the 1990s. Since the early 2000s, in the context of free movement within the European Union, immigration from Eastern Europe (mainly from Poland, Rumania, Bulgaria, and Hungary) has become increasingly relevant. Students whose parents migrated from Eastern Europe perform worse in primary (e.g., Stanat et al. 2017) and secondary school (e.g., Stanat et al. 2016) than majority students; however, the achievement gap relative to the majority population is smaller than that of Turkish minority students.

Stereotypes among Germans regarding ethnic minorities are mostly negative (Glock and Karbach 2015), particularly those regarding the Turkish minority (Asbrock 2010; Mummendey et al. 1982). One of the few studies that examined the content of such stereotypes found that the respondents attributed characteristics, such as “primitive”, “traditional”, “community”, or “male-dominated” to people of Turkish origin. In contrast, the respondents associated the category “native” with more positive attributes, such as “neat”, “achievement-oriented”, “rational”, or “wealthy” (Kahraman and Knoblich 2000). Experimental research confirms that the negative stereotypes regarding Turkish minority members are also prevalent among German teachers (Glock and Krolak-Schwerdt 2013).

In this context, I rely on the social-psychological assumption of impression formation to explain a possible emergence of teacher expectation bias and associations between such bias and ethnic achievement gaps during first grade. Due to the nature of the analysed data, which include students from Turkish and Eastern European immigrant families, I focus on students’ ethnic rather than their racial backgrounds. I expect that stereotypes regarding the achievement of different ethnic groups of students are associated with teacher expectations for individual students from these groups at the beginning of first grade (Hypothesis 1). I further assume that more general stereotypes that refer to achievement-related attributes, such as the general knowledge, attentiveness, and motivation of ethnic minority students, also trigger ethnic bias in teachers’ expectations (Hypothesis 2). Moreover, by triggering teacher expectation bias, both types of stereotypes may lead to self-fulfilling prophecies and, thus, contribute to ethnic differences in the scholastic performance during first grade. Accordingly, ethnic minority students taught by teachers with more positive ethnic achievement stereotypes or teachers with more positive achievement-related stereotypes should achieve higher academic performance (Hypothesis 3). This assumption implies that inaccurate teacher stereotypes induce group-specific teacher expectation inaccuracy that results in teacher expectation effects on student achievements. Hence, teacher expectation inaccuracy should mediate the statistical effects of teacher stereotypes on student achievements (Hypothesis 4).

4 Data and methods

4.1 Sample

This study draws on data from the research project Kompetenzerwerb und Lernvoraussetzungen (KuL; English translation: Competence Acquisition and Learning Precondition; Kristen et al. 2018).Footnote 1 The total sample included N = 1065 first graders from N = 67 classrooms in N = 39 primary schools in Germany. The schools sampled were located in the Ruhr, which is a large polycentric urban area located in the federal state of North-Rhine Westphalia. The population living in this area is characterized by high ethnic diversity and was chosen with the aim of mapping everyday school life in diverse contexts. The data were collected at the beginning (t1) and end (t2) of the 2013/2014 school year.

Data collection started shortly after the beginning of the first school year, i.e., when the preceding teacher-student interaction was minimal. Thus, the survey was designed to ensure that student attributes were not affected by teacher expectation effects. Additionally, due to the minimal teacher-student contact prior to the survey, the problem of unobserved heterogeneity should be less severe than in instances of longer periods of prior interaction.

The current study relies on information obtained from standardized achievement tests, interviews with students, and questionnaires completed by teachers at t1 and t2. Additionally, telephone interviews with parents were conducted at t1. The whole survey and all instruments were validated at two separate schools in the year preceding the main study.

In the analyses, 39 students were excluded from the sample since either information regarding teacher expectations was missing or the teachers left their class between t1 and t2. In total, 19 students were born abroad (first generation). These students were excluded from the sample. Thus, the analysed sample comprises N = 1007 students and N = 64 teachers. In the analyses of the mathematical domain, another 87 students were removed from the sample because five teachers did not teach mathematics (N = 920 students and N = 59 teachers remained).

The teachers in the analysed sample were, on average, 42 years old (SD = 8.93) and had an average working experience of twelve years (SD = 8.89). The teachers were predominantly female (91%) and belonged to the German majority population (92%). Two teachers had a Polish background.

4.2 Instruments

Two measures were used to examine teacher stereotypes. First, the teachers were asked to report their beliefs regarding the average reading and math achievements of majority, ethnic minority, and Turkish minority students on an 11-point scale (for the precise wording, see Fig. 4 in Appendix 1). Each of the six evaluations was performed in comparison with the average achievement of all German first graders. These measures were used to capture the teachers’ achievement stereotypes. Second, five items recorded the teachers’ agreement with negative statements regarding the school-related attributes of ethnic minority students on a five-point scale. The items referred to the interest, attentiveness, motivation, effort, and pre-knowledge of students from ethnic minority families (for the precise wording, see Fig. 5 in Appendix 1). Each teacher’s answers were summed to build a scale of negative achievement-related stereotypes (α = 0.88). The stereotypes were measured at t2 to prevent the activation of stereotypes at t1 and subsequent bias in their expectations and teaching during the first school year. This procedure was also chosen because the extant research corroborates that stereotypes are stable over time and, thus, should not change during one school year (e.g., Madon et al. 2011).

To measure teacher expectations, at t1, the teachers were asked to rate the expected performance during the upcoming first school year of each participating student in their class. Three items were summed to build a scale indicating the teacher’s expectation regarding each child’s achievement in the linguistic domain (α = 0.94), and another two items were summed to capture expectations in the mathematical domain (α = 0.94) (for the precise wording of the items, see Fig. 6 in Appendix 1).

To compare the teacher expectations for ethnic majority students with those for ethnic minority students, I used information regarding the birth countries of the students and their families that was obtained from telephone interviews with parents at t1. It was possible to distinguish among the following four ethnic groups: majority students (N = 547), students with a Turkish background (N = 98), students with an Eastern European background (N = 102) and students with other ethnic minority backgrounds (N = 130). The Eastern European category included children whose families originated from countries that once belonged to the Soviet Union, Poland, the Czech Republic, Bulgaria, Rumania, Hungary, Slovakia, and Slovenia. A student was identified as a member of a minority group if at least one parent was born abroad.

The subscales phonological awareness (α = 0.82) and reading (α = 0.96) of the computer-based FIPS assessment that the research team carried out with each participating child at the beginning of the school year were used as the measures of language skills at t1 (Bäuerlein et al. 2012). As measures of mathematical skills at t1, the students completed the mathematics subscale of the FIPS assessment (α = 0.92). These instruments were specifically designed to measure the linguistic and mathematical skills of school beginners. Additionally, I used two scales to measure the students’ cognitive abilities at t1, namely, a deductive reasoning test (CFT1; (Weiß and Osterland 1997) and the working memory subscale implemented in the FIPS assessment (Bäuerlein et al. 2012) (α = 0.76).

For the analyses of student achievements at t2, I used the results of the reading comprehension test ELFE1-6 (Lenhard and Schneider, 2006). The measures of mathematical skills were provided by the tests DEMAT1 + (Krajewski et al. 2002) and MBK-1 (Ennemoser et al. 2017), which I summed into one score representing mathematical skills at t2.

Teachers rely on student motivation when forming their expectations (Gentrup et al. 2018). Therefore, I considered the students’ enjoyment of learning (a sum-scale comprising 13 items; α = 0.78) and effort (13 items; α = 0.70), as measured by personal interviews at t1. For this purpose, I used an adapted form of the FEESS1-2 scale during personal interviews with the children (Rauer and Schuck 2004).

To consider the students’ social backgrounds, I used the highest values among the parents with regard to the International Socio-Economic Index of occupational status (HISEI) (Ganzeboom et al. 1992) and educational attainment. This information was gathered during telephone interviews with the parents. The latter variable distinguished among lower secondary, upper secondary and tertiary education.

Information from the parent interviews was used to control for the students’ gender.

Finally, I controlled for the socioeconomic and ethnic composition of the classroom to account for the fact that teacher expectation bias might vary based on the classroom composition (Timmermans et al. 2015). Thus, the teachers were asked to indicate the number of students in their classes who had at least one parent with a tertiary education and the number of students who originated from immigrant families.

4.3 Model estimation

To account for the nested structure of the data (i.e., teacher expectations regarding the students are nested in the teachers), all the multivariate results are based on multilevel linear regressions (Allison 2009), with the students as the first level and the teachers as the second level of analysis. To consider the relationships between teacher stereotypes and teacher expectation bias (hypotheses 1 and 2), I regressed the teacher expectations in the linguistic and mathematics domains (separate models) at t1 on the students’ ethnic backgrounds and teachers’ stereotypes while controlling for reading skills and phonological awareness (only in the models referring to the linguistic domain), mathematical skills (only in the model referring to the mathematical domain), general cognitive abilities, motivation, HISEI, parental education, and gender. Additionally, I specified cross-level interactions between the students’ ethnic backgrounds and teacher stereotypes to address the question of whether teachers with more negative stereotypes had lower expectations for individual ethnic minority students. In separate models, I used the teachers’ achievement stereotypes regarding ethnic minority students (Model 1) and their achievement stereotypes regarding Turkish minority students (Model 2) while controlling for achievement stereotypes regarding the majority. The predictions of teacher expectations in the linguistic domain included the achievement stereotypes regarding reading skills, and the predictions of expectations in mathematics included the achievement stereotypes regarding math skills. In further models, the cross-level interaction included the teachers’ agreement with negative achievement-related stereotypes regarding ethnic minority students (Model 3). The models can be expressed as follows:

In this formula, \(y_{it}\) refers to the expectation of teacher t for student i. \(\beta_{01}\) is the effect of a student variable \(x,\) such as ethnic background. \(\beta_{10}\) is the effect of a teacher stereotype variable \(z,\) such as a teacher’s belief regarding the average reading skills of ethnic minority students. \(\beta_{11}\) represents the effect of a cross-level interaction, such as between the students’ ethnic background and the teacher stereotype variable. The model specifications allowed the effects of the students’ ethnic backgrounds and their achievements to vary randomly across the teachers.

A similar procedure was chosen to test the assumption that by inducing expectation bias and adding to self-fulfilling prophecies, teacher stereotypes are related to subsequent student achievements in reading and mathematics. In these models, \(y_{it}\) refers to student achievement at t2, while \(\beta_{01}\) represents the effect of a student characteristic, such as achievement at t1, cognitive abilities, HISEI, parental education and gender, while \(\beta_{11}\) again represents the effect of a cross-level interaction between a student’s ethnic background and one of the teacher stereotype variables. The latter effect could inform whether ethnic minority students experienced lower achievement gains throughout the first school year when their teachers had more negative stereotypes (Hypothesis 3). To examine whether teacher expectation inaccuracy mediates the possible relationship between teacher stereotypes and student achievement (Hypothesis 4), teacher expectation inaccuracy was added as an additional explanatory variable in the following step. This variable was generated separately for the linguistic and mathematics domains. For each child, this variable represents the residuals from regressions of (domain-specific) teacher expectations on (domain-specific) student achievement, cognitive abilities, and motivation (e.g., Madon et al. 1998) (results not displayed, see Gentrup et al. 2020).

Variables with missing information were imputed using the fully conditional specification (van Buuren and Groothuis-Oudshoorn 2011), and then, the parameters from the 50 resulting data sets were pooled according to Rubin’s rules (Rubin 1987).

5 Results

5.1 Descriptive results

Figure 1 describes the distributions of the six achievement stereotype variables. The mean differences between the variables indicate that the teachers believed that majority students performed better in reading on average than ethnic minority students and Turkish minority students (see upper panel in Fig. 1). The teachers also believed that, on average, majority students have higher mathematical skills than ethnic minority and Turkish minority students (see the lower panel in Fig. 1), but the average expected ethnic achievement gap was smaller than that in reading. Most importantly, Fig. 1 reveals considerable differences in the teachers’ achievement stereotypes. Thus, different teachers expected different average achievements for the same groups of students. Such variation seems to have been higher in the reading domain than the mathematical domain.

The distribution of the teachers’ agreement with negative achievement-related stereotypes regarding ethnic minority students is displayed in Fig. 2. The mean of this variable (M = 2.7, SD = 0.68) falls below the scale’s theoretical midpoint, indicating that most teachers tended to disagree with negative generalizations regarding ethnic minority students.

Table 1 displays the descriptive statistics of the remaining variables in the analysed sample separated by the students’ ethnic backgrounds. The data reveal that the teachers expressed the lowest expectations for Turkish minority students. The differences relative to the average expectations for majority students were statistically significant in both domains. The highest expectations can be observed regarding the linguistic and mathematical achievements of students with an Eastern European background, although the means did not statistically significantly differ from those regarding the majority group.

Furthermore, Table 1 shows that the linguistic and mathematical competencies of Turkish minority students at the beginning of the school year were significantly lower than those of majority students. The Eastern European group outperformed all other groups in both domains, although the differences compared to the majority were not statistically significant. Notably, the differences in student achievements for the different ethnic groups aligned with the teachers’ expectations. At the same time, no significant mean differences were found across the ethnic groups with regard to cognitive abilities (as measured by the deductive reasoning and working memory tests) and motivation (as measured by enjoyment of learning and effort).

The ethnic achievement gaps seemed less pronounced at the end of the school year. However, the mean differences in reading and mathematical skills between majority and Turkish minority students were still significant.

5.2 Multivariate relationships between teacher stereotypes and teacher expectations

The multilevel regression analyses revealed that at the beginning of the school year, the teacher expectations in the linguistic domain were lower for Turkish minority students after considering the students’ reading skills, cognitive abilities, motivation, SES, and gender (see Model 0a in Table 4 in Appendix 2). In contrast, teacher expectations were significantly higher for students of Eastern European backgrounds in the mathematical field (see Model 0b in Table 5 in Appendix 2; see also Lorenz 2018; Lorenz et al. 2016).

In the following step, I aimed to determine how these residual effects of the students’ ethnic backgrounds relate to differences in teachers’ stereotypes. Therefore, Fig. 3 depicts the cross-level interaction effects between the students’ ethnic backgrounds and the teachers’ stereotypes on the teacher expectation predictions. In the linguistic domain (upper panel in Fig. 3), the teachers’ achievement stereotypes regarding ethnic minority students’ reading skills were insignificantly related to the students’ ethnic backgrounds (see Model 1a). In Model 2a, however, the cross-level interactions were significant for Turkish minority students (β = 0.19, p ≤ 0.05) and ethnic minority students (β = 0.17, p ≤ 0.05). Thus, Hypothesis 1 was confirmed, indicating that more positive stereotypes regarding the reading achievement of Turkish minority children resulted in more positive teacher expectations for Turkish minority and other minority students and smaller gaps from the teachers’ expectations for majority students.

Notes: Marginal effects based on the coefficients reported in tables 4 and 5 in Appendix 2. Unembodied controls: student achievement and motivation (t1), HISEI, parental education, gender, socioeconomic and ethnic classroom composition. Nstudents = 1007, Nteachers = 64. Competence acquisition and learning preconditions (KuL), author’s calculations

Marginal effects of teacher stereotypes on teacher expectations at t1.

Furthermore, Hypothesis 2 was confirmed, as significant interaction effects were observed in Model 3a between the teachers’ achievement-related stereotypes and being a Turkish minority (β = − 0.18, p ≤ 0.05) or an Eastern European minority member (β = − 0.16, p ≤ 0.1). This indicated that the teachers who agreed more with negative achievement-related stereotypes expected lower linguistic achievements for individual Turkish minority and Eastern European minority students compared to what they expected for majority students.

In the mathematical domain (lower panel in Fig. 3), the cross-level interaction effects between the students’ ethnic backgrounds and teacher achievement stereotypes were insignificant (see models 1b and 2b). However, Hypothesis 2 was confirmed, as the negative achievement-related stereotypes among the teachers were significantly associated with ethnic teacher expectation bias as follows: the expectations for Turkish minority (β = − 0.13, p ≤ 0.1) and Eastern European background students (ß = -0.17, p ≤ 0.1) decreased as the agreement with such stereotypes increased (see Model 3b).

5.3 Multivariate relationships between teacher stereotypes and student achievement

Table 2 shows the coefficients from multilevel regressions of the students’ reading skills at the end of the school year. Notably, there were no significant ethnic differences in this outcome after controlling for reading skills and cognitive abilities at t1, as well as gender, SES, and the classroom composition (Model 1). Models 2, 3, and 4 additionally report the coefficients of the cross-level interaction effects between the students’ ethnic backgrounds and each of the teacher stereotype measures. Contradicting Hypothesis 3, none of these interaction effects were significant. Thus, the teachers’ stereotypes were unrelated to ethnic differences in the students’ reading skills at t2. Adding the measure of teacher expectation inaccuracy at t1 to models 5, 6, and 7 revealed that this inaccuracy significantly predicted the end-of-school-year reading achievement. This finding is consistent with previous self-fulfilling-prophecy research. In these models, the interaction effects between the students’ ethnic backgrounds and teacher stereotypes remained unchanged, which contradicts Hypothesis 4.

A very similar picture emerged from the analysis of the students’ mathematical skills at t2 (see Table 3). I observed no statistically significant ethnic differences in this outcome (Model 1). Additionally, none of the teacher stereotype measures was related to ethnic differences in mathematics achievements (models 2, 3, and 4). This finding did not change after controlling for teacher expectation inaccuracies, which significantly predicted the end-of-school-year performance in math (models 5, 6, and 7).

6 Discussion

This article examined whether stereotypes among teachers are associated with ethnic bias in their achievement expectations and whether such bias contributes to the emergence of self-fulfilling prophecies that exaggerate ethnic achievement gaps in reading and mathematics during first grade. Drawing upon a sample of students beginning school for the first time and their teachers in Germany, this study first confirmed that some teachers had negative stereotypes regarding the achievement and achievement-related attributes of ethnic minority students, whereas other teachers had more positive stereotypes. That is, part of the teachers believed that majority students substantially outperform their ethnic minority peers and that the latter group is generally less attentive, eager to learn, interested and knowledgeable. Other teachers, instead, believed that ethnic achievement gaps are smaller and agreed less with negative achievement-related stereotypes regarding ethnic minority students.

Second, my study is one of very few to use non-experimental data and to show that teacher stereotypes were systematically associated with teacher expectation bias along with the students’ ethnic backgrounds. Specifically, I found that after controlling for the students’ reading skills, cognitive abilities, motivation, SES, gender, and classroom composition, only those teachers with more negative stereotypes regarding the overall reading achievement of Turkish minority students had negatively biased expectations regarding the linguistic skills of individual Turkish minority students. In contrast, I found no bias in the expectations for Turkish minority students among teachers with more positive achievement stereotypes for the Turkish minority group. In the mathematical domain, no such relationships were found. However, stereotypes regarding achievement-related student characteristics were critical for expectation bias in both domains. That is, ceteris paribus, teachers who believed that the interest, attentiveness, motivation, effort, and pre-knowledge of minority youth were lower expected bigger differences in the linguistic and mathematical achievements between ethnic minority and majority students in their class. This evidence suggests that ethnic stereotypes shape teachers’ evaluations of individual students and induce ethnic bias in their achievement expectations.

Third, consistent with self-fulfilling-prophecy research (see Wang et al. 2018) and previous studies that also relied on the data used in the current study (Gentrup et al. 2020; Lorenz 2018), I found that the teacher expectation inaccuracy at the beginning of the first grade predicted students’ end-of-year achievements in reading and math. However, the conclusion of my results concerning the contribution of this phenomenon to ethnic achievement gaps did not meet my theoretical assumptions or those of other scholars (e.g., Jussim et al. 2009b). In particular, teacher stereotypes were unrelated to ethnic differences in academic achievements during the first school year. This finding also contradicts the results of a study conducted in the Netherlands. There, implicit measures of teacher stereotypes were used to predict test scores in mathematics (van den Bergh et al. 2010). However, notably, this study failed to consider the initial differences in student abilities and skills in their investigation of teacher expectation bias and teacher expectation effects on academic achievement. As my results suggest, failing to do so results in overestimations of the effects of teacher stereotypes on student achievements. One reason for such overestimations might be unobserved heterogeneity.

6.1 Limitations

While the current study contributes to the existing research by providing empirical tests of as-yet-untested theoretical assumptions, some limitations should be noted. First, the assumption that teachers rely on ethnic and racial stereotypes when evaluating ethnic minority students could not be tested directly. The processes of stereotype activation and application could only be examined indirectly. Implicit measures used in experimental studies (e.g., Glock and Karbach 2015) might provide an opportunity to investigate the assumed processes more directly.

Second, the sample was not representative of German primary school teachers or students. The sample’s average socioeconomic composition differed from that of representative samples, such as the 2016 National Assessment Study, as it had a slightly higher average HISEI of M = 54 compared to M = 49 among primary school students in North Rhine-Westphalia—the Federal State in which the data I analysed were collected (see Stanat et al. 2017). This difference is presumably because participation in the KuL study was voluntary and the return rate was fairly low (eight percent at the school level; see Lorenz 2018). Thus, the teachers who participated in the KuL study might have been more engaged than the teachers in Germany on average. Because one could expect highly engaged teachers to be particularly eager to accurately evaluate students, the extent of bias in teacher expectations might have been underestimated in the current study. A larger, unbiased sample is necessary to evaluate the effect sizes more precisely.

7 Conclusion

In conclusion, my study advances the debate regarding the issue of teacher discrimination in education, as it indicates that within ecologically valid settings, stereotypes among teachers cause bias in their evaluations of ethnic minority students. On the one hand, this evidence counters a common criticism of discrimination research, namely, that the residual effects of student ethnicity on teacher evaluations are mainly driven by unobserved heterogeneity. On the other hand, I could not confirm a long-lasting assumption in the self-fulfilling prophecy research, namely, that teacher stereotypes and the resulting expectation bias are associated with ethnic disparities in scholastic performance. Although I found that initial teacher expectation inaccuracy was related to subsequent student achievement, my study questions whether this phenomenon results in a subtle form of discrimination that might be related to ethnic achievement gaps. In future studies on teacher discrimination, a vital concern should be to verify whether my conclusion also applies if one examines the long-term development of scholastic performance. Furthermore, it appears worthwhile to investigate other types of teacher stereotypes, such as those associated with the SES of students, and to test for possible relationships with social disparities in educational outcomes. This approach could enable scholars to draw more reliable conclusions regarding the role of teacher expectations in the formation of educational inequality.

Data availability

The data are stored and access can be applied for at the following web address: http://doi.org/10.5159/IQB_KuL_v1

Code availability

Stata codes for replication of the results are available from the author upon request.

Notes

This interdisciplinary research project was conducted under the leadership of Prof. Dr. Cornelia Kristen (Otto-Friedrich-Universität Bamberg), Prof. Dr. Irena Kogan (Universität Mannheim), and Prof. Dr. Petra Stanat (Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin). The author of the current study was the coordinator of the project.

References

Allison, P. (2009). Fixed effects regression models. Los Angeles: SAGE Publications. http://methods.sagepub.com/book/fixed-effects-regression-models.

Anderson-Clark, T. N., Green, R. J., & Henley, T. B. (2008). The relationship between first names and teacher expectations for achievement motivation. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 27(1), 94–99. https://doi.org/10.1177/0261927X07309514

Asbrock, F. (2010). Stereotypes of social groups in Germany in terms of warmth and competence. Social Psychology, 41, 76–81. https://doi.org/10.1027/1864-9335/a000011

Babad, E. (2009). The social psychology of the classroom. New York: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203872475

Bäuerlein, K., Beinicke, A., Berger, N., Faust, G., Jost, M., & Schneider, W. (2012). Performance indicators in primary schools: A computer-based diagnostic tool for detecting the initial learning capabilities and the learning development of children starting school. Göttingen: Hogrefe.

Bonefeld, M., & Dickhäuser, O. (2018). (Biased) grading of students’ performance: Students’ names, performance level, and implicit attitudes. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00481

de Boer, H., Bosker, R. J., & van der Werf, M. P. C. (2010). Sustainability of teacher expectation bias effects on long-term student performance. Journal of Educational Psychology, 102(1), 168–179. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017289

Devine, P. G. (1989). Stereotypes and prejudice: Their automatic and controlled components. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 56(1), 5–18. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.56.1.5

Ennemoser, M., Krajewski, K., & Sinner, D. (2017). Test of basic mathematics proficiency at school enrolment. Göttingen: Hogrefe. https://doi.org/10.2378/peu2019.art15d

Farkas, G. (2003). Racial disparities and discrimination in education: What do we know, how do we know it, and what do we need to know? Teachers College Record, 105(6), 1119–1146. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9620.00279

Fiske, S. T. (1998). Stereotyping, prejudice, and discrimination. In S. T. Fiske, D. T. Gilbert, & G. Lindzey (Eds.), The Handbook of Social Psychology (4th ed., Vol. 1–2, pp. 357–411). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Fiske, S. T., Lin, M., & Neuberg, S. L. (1999). The continuum model: Ten years later. In S. Chaiken & Y. Trope (Eds.), Dual-process theories in social psychology (pp. 231–254). New York: Guilford Press.

Ganzeboom, H. B. G., De Graaf, P. M., & Treiman, D. J. (1992). A standard international socio-economic index of occupational status. Social Science Research, 21(1), 1–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/0049-089X(92)90017-B

Gawronski, B., Geschke, D., & Banse, R. (2003). Implicit bias in impression formation: Associations influence the construal of individuating information. European Journal of Social Psychology, 33(5), 573–589. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.166

Gentrup, S., Lorenz, G., Kristen, C., & Kogan, I. (2020). Self-fulfilling prophecies in the classroom: Teacher expectations, teacher feedback and student achievement. Learning and Instruction, 66, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2019.101296

Gentrup, S., Rjosk, C., Stanat, P., & Lorenz, G. (2018). Teachers‘ perceptions of students‘ motivation and learning behaviour and their role in biased teacher expectations. Zeitschrift Für Erziehungswissenschaft, 21(4), 867–891. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11618-018-0806-2

Glock, S. (2016). Does ethnicity matter? The impact of stereotypical expectations on in-service teachers’ judgments of students. Social Psychology of Education, 19(3), 493–509. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-016-9349-7

Glock, S., & Karbach, J. (2015). Preservice teachers’ implicit attitudes toward racial minority students: Evidence from three implicit measures. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 45, 55–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2015.03.006

Glock, S., & Krolak-Schwerdt, S. (2013). Does nationality matter? The impact of stereotypical expectations on student teachers’ judgments. Social Psychology of Education, 16(1), 111–127. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-012-9197-z

Hamilton, D. L. (1981). Cognitive processes in stereotyping and intergroup behavior. London: Psychology Press. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315668758

Harris, M. J., & Rosenthal, R. (1985). Mediation of interpersonal expectancy effects: 31 meta-analyses. Psychological Bulletin, 97(3), 363–386. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.97.3.363

Hattie, J. A. C. (2009). Visible learning. A synthesis of over 800 meta-analyses relating to achievement. London: Routledge.

Heath, A. F., Rothon, C., & Kilpi, E. (2008). The second generation in Western Europe: Education, unemployment, and occupational attainment. Annual Review of Sociology, 34(1), 211–235. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.34.040507.134728

Hilton, J. L., & von Hippel, W. (1996). Stereotypes. Annual Review of Psychology, 47(1), 237–271. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.47.1.237

Jussim, L., Cain, T. R., Crawford, J. T., Harber, K. D., & Cohen, F. (2009a). The unbearable accuracy of stereotypes. In T. D. Nelson (Ed.), Handbook of prejudice, stereotyping, and discrimination (pp. 199–227). New York: Psychology Press.

Jussim, L., Eccles, J., & Madon, S. (1996). Social perception, social stereotypes, and teacher expectations: Accuracy and the quest for the powerful self-fulfilling prophecy. In M. P. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 28, pp. 281–388). New York: Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60240-3

Jussim, L., Robustelli, S. L., & Cain, T. R. (2009b). Teacher expectations and self-fulfilling prophecies. In K. R. Wentzel & A. Wigfield (Eds.), Handbook of motivation at school (pp. 349–380). New York: Routledge.

Kahraman, B., & Knoblich, G. (2000). «Stechen statt sprechen»: Valenz und aktivierbarkeit von stereotypen über Türken. Zeitschrift für Sozialpsychologie, 31(1), 31–43. https://doi.org/10.1024//0044-3514.31.1.31

Krajewski, K., Küspert, P., & Schneider, W. (2002). German mathematics test for first grade (DEMAT 1+). Göttingen: Hogrefe.

Kristen, C., & Granato, N. (2007). The educational attainment of the second generation in Germany: Social origins and ethnic inequality. Ethnicities, 7(3), 343–366. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468796807080233

Kristen, C., Kogan, I., Stanat, P., Lorenz, G., Gentrup, S., Rahmann, S. (2018). Competence acquisition and learning preconditions (KuL). IQB–Institut zur Qualitätsentwicklung im Bildungswesen. http://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5159/IQB_KuL_v1.

Lenhard, W., & Schneider, W. (2006). ELFE 1–6. A reading comprehension test for first to sixth graders. Göttingen: Hogrefe.

Lorenz, G. (2018). Self-fulfilling prophecies in schools. Teacher expectations and the scholastic performance of immigrant children. Wiesbaden: Springer.

Lorenz, G., Gentrup, S., Kristen, C., Stanat, P., & Kogan, I. (2016). Stereotypes among teachers? a study of systematic bias in teacher expectations. KZfSS Kölner Zeitschrift Für Soziologie Und Sozialpsychologie, 68(1), 89–111. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11577-015-0352-3

Lucas, S. R. (2008). Theorizing discrimination in an era of contested prejudice: Discrimination in the United States. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Madon, S., Jussim, L., & Eccles, J. (1997). In search of the powerful self-fulfilling prophecy. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 72(4), 791–809. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.72.4.791

Madon, S., Jussim, L., Keiper, S., Eccles, J., Smith, A., & Palumbo, P. (1998). The accuracy and power of sex, social class, and ethnic stereotypes: A naturalistic study in person perception. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 24(12), 1304–1318. https://doi.org/10.1177/01461672982412005

Madon, S., Willard, J., Guyll, M., & Scherr, K. C. (2011). Self-fulfilling prophecies: Mechanisms, power, and links to social problems: self-fulfilling prophecies. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 5(8), 578–590. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2011.00375.x

Meissel, K., Meyer, F., Yao, E. S., & Rubie-Davies, C. M. (2017). Subjectivity of teacher judgments: Exploring student characteristics that influence teacher judgments of student ability. Teaching and Teacher Education, 65, 48–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2017.02.021

Merton, R. K. (1948). The self-fulfilling prophecy. The Antioch Review, 8(2), 193–210. https://doi.org/10.2307/4609267

Mummendey, H. D., Bolten, H.-G., & Isermann-Gerke, M. (1982). Experimental test of the Bogus-Pipeline-Paradigma: Attitudes towards Turks, Germans, and Dutchman. Zeitschrift Für Sozialpsychologie, 13(4), 300–311.

OECD. (2016). PISA 2015 results (volume I): Excellence and equity in education. Paris: OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development).

Peterson, E. R., Rubie-Davies, C., Osborne, D., & Sibley, C. (2016). Teachers’ explicit expectations and implicit prejudiced attitudes to educational achievement: Relations with student achievement and the ethnic achievement gap. Learning and Instruction, 42, 123–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2016.01.010

Rauer, W., & Schuck, K. D. (2004). Questionnaire for emotional and social school experiences of first- and second-grade students: FEESS 1–2. Göttingen: Beltz Test.

Ready, D. D., & Wright, D. L. (2011). Accuracy and inaccuracy in teachers’ perceptions of young children’s cognitive abilities: The role of child background and classroom context. American Educational Research Journal, 48(2), 335–360. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831210374874

Rosenthal, R., & Jacobson, L. (1968). Pygmalion in the classroom: Teacher expectations and student intellectual development. New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston. https://doi.org/10.1002/1520-6807(196904)6:2%3c212::AID-PITS2310060223%3e3.0.CO;2-U

Rubie-Davies, C. M., Weinstein, R. S., Huang, F. L., Gregory, A., Cowan, P. A., & Cowan, C. P. (2014). Successive teacher expectation effects across the early school years. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 35(3), 181–191. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2014.03.006

Rubin, D. B. (1987). Multiple imputation for nonresponse in surveys. New York: John Wiley and Sons.

Schneider, D. J. (2005). The psychology of stereotyping. New York: Guilford Press.

Stanat, P., Böhme, K., Schipolowski, S., & Haag, N. (2016). IQB trends in student achievement 2015. The second national assessment of language proficiency at the end of the ninth grade. Münster: Waxmann.

Stanat, P., Schipolowski, S., Rjosk, C., Weirich, S., & Haag, N. (2017). IQB Trends in student achievement 2016. The second national assessment of German and mathematics proficiencies at the end of fourth grade. Münster: Waxmann.

Tenenbaum, H. R., & Ruck, M. D. (2007). Are teachers’ expectations different for racial minority than for European American students? A meta-analysis. Journal of Educational Psychology, 99(2), 253–273. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.99.2.253

Timmermans, A. C., Kuyper, H., & van der Werf, G. (2015). Accurate, inaccurate, or biased teacher expectations: Do Dutch teachers differ in their expectations at the end of primary education? British Journal of Educational Psychology, 85(4), 459–478. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12087

Tobisch, A., & Dresel, M. (2017). Negatively or positively biased? dependencies of teachers’ judgments and expectations based on students’ ethnic and social backgrounds. Social Psychology of Education, 20(4), 731–752. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-017-9392-z

van Buuren, S., & Groothuis-Oudshoorn, K. (2011). MICE: Multivariate imputation by chained equations in R. Journal of Statistical Software, 45(3), 1–67.

van den Bergh, L., Denessen, E., Hornstra, L., Voeten, M., & Holland, R. W. (2010). The implicit prejudiced attitudes of teachers: Relations to teacher expectations and the ethnic achievement gap. American Educational Research Journal, 47(2), 497–527. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831209353594

Van Ewijk, R. (2011). Same work, lower grade? student ethnicity and teachers’ subjective assessments. Economics of Education Review, 30(5), 1045–1058. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2011.05.008

Wang, S., Rubie-Davies, C. M., & Meissel, K. (2018). A systematic review of the teacher expectation literature over the past 30 years. Educational Research and Evaluation, 24(3–5), 124–179. https://doi.org/10.1080/13803611.2018.1548798

Weiß, R. H., & Osterland, J. (1997). Culture fair intelligence test 1: CFT1. Hogrefe: Hogrefe.

Wenz, S. E., Olczyk, M., Lorenz, G. (2016). Measuring teachers’ stereotypes in the NEPS (NEPS Survey Paper No. 3). Leibniz Institute for Educational Trajectories, National Educational Panel Study.

Zebrowitz, L. A. (1996). Physical appearance as a basis of stereotyping. In C. N. Macrae, C. Stangor, & M. Hewstone (Eds.), Stereotypes and stereotyping (pp. 79–120). New York: Guilford Press.

Acknowledgements

I thank Cornelia Kristen, Kristin Schotte, Sarah Gentrup, Zerrin Salikutluk, and Aileen Edele for their valuable comments on an earlier version of the manuscript.

Funding

The author acknowledges financial support from the Federal Ministry of Education and Research of Germany (Project Number 01JC1117). The responsibility for the content of this publication lies with the author.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

The author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

Consent for participate

Participation in the KuL study was voluntary. The teachers rated their expectations for all the students in their classes for whom parents provided written consent to participate in the study.

Ethics approval

The KuL study received approval from the research ethics committee of the University of Mannheim. The author has never been affiliated with this university. Prof. Dr. Irena Kogan from the University of Mannheim was part of the research team that collected the data analysed in the current study, but she has never been part of the research ethics committee.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Excerpts from the teacher questionnaire

Appendix 2: Full results from multilevel regressions predicting teacher expectations at the beginning of first grade

Appendix 3: Full results from multilevel regressions predicting student skills at the end of first grade

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lorenz, G. Subtle discrimination: do stereotypes among teachers trigger bias in their expectations and widen ethnic achievement gaps?. Soc Psychol Educ 24, 537–571 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-021-09615-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-021-09615-0