Abstract

Measuring ecological and economic impacts of invasive species is necessary for managing invaded food webs. Based on abundance, biomass and diet data of autochthonous and allochthonous fish species, we proposed a novel approach to quantifying trophic interaction strengths in terms of number of individuals and biomass that each species subtract to the others in the food web. This allowed to estimate the economic loss associated to the impact of an invasive species on commercial fish stocks, as well as the resilience of invaded food webs to further perturbations. As case study, we measured the impact of the invasive bass Micropterus salmoides in two lake communities differing in food web complexity and species richness, as well as the biotic resistance of autochthonous and allochthonous fish species against the invader. Resistance to the invader was higher, while its ecological and economic impact was lower, in the more complex and species-rich food web. The percid Perca fluviatilis and the whitefish Coregonus lavaretus were the two species that most limited the invader, representing meaningful targets for conservation biological control strategies. In both food webs, the limiting effect of allochthonous species against M. salmoides was higher than the effect of autochthonous ones. Simulations predicted that the eradication of the invader would increase food web resilience, while that an increase in fish diversity would preserve resilience also at high abundances of M. salmoides. Our results support the conservation of biodiverse food webs as a way to mitigate the impact of bass invasion in lake ecosystems. Notably, the proposed approach could be applied to any habitat and animal species whenever biomass and diet data can be obtained.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Invasive species are among the main causes of biodiversity loss and changes in ecosystems (Gozlan et al. 2010; Gallardo et al. 2016), and their impact is expected to increase worldwide due to climate warming and human action (McClelland et al. 2018; Ricciardi et al. 2017). Resource consumption by invaders in relation to resource availability (i.e. the functional response by invaders, sensu Dick et al. 2017a) is a central element in several hypotheses predicting their success in invaded habitats (Dick et al. 2017a). Nevertheless, measurements of functional responses are often performed under simplified conditions. Specifically, they do not take into account the multiple biotic interactions that constrain invasive species in food webs, and may thus fail to predict their impact in real ecosystems (see Vonesh et al. 2017 for a discussion on this point). Thus, while research in the field has increased during recent years (Dick et al. 2017b; Laverty et al. 2017; Corrales et al. 2019), our ability to measure the ecological and economic impact of invaders in natural communities is still limited (Kulhanek et al. 2011; Crystal-Ornelas and Lockwood 2020).

In this context, the quantification of the impact of biological invasions on complex food webs and key ecosystem services (including the productivity of commercially exploited species) is necessary to formulate effective management strategies (Gozlan et al. 2010; Davies and Britton 2015; Latombe et al. 2017). In parallel, conservation biological control strategies would benefit from a quantitative measure of the resistance by autochthonous and allochthonous species against recently established invaders, thus enabling the identification of meaningful conservation targets (Frost et al. 2019). Indeed, invaders’ success can vary greatly depending on the structure of invaded food webs (Dzialowski et al. 2007; Jackson et al. 2013; Smith‐Ramesh et al. 2017; Vonesh et al. 2017), through mechanisms of biotic resistance by competitors (competitive resistance) and predators (consumptive resistance) (Britton 2012; Alofs and Jackson 2014; Smith‐Ramesh et al. 2017; Rehage et al. 2019). However, field studies comparing consumptive and competitive resistance at the whole food web level are lacking (Alofs and Jackson 2014). Similarly, there is a lack of information about the effects of invaders on the dynamic properties of food webs, including web resilience to further perturbations. This hinders an effective conservation and management of invaded communities, which may be exposed to other environmental stressors (e.g. habitat degradation) that interact with invasion, impairing the persistence of food webs (Didham et al. 2007; Prior et al. 2017; Norbury and van Overmeire 2019).

In recent years, the study of invaded food webs has benefited from the application of stable isotope analysis coupled with Bayesian mixing models to the description of trophic links between species (Bond et al. 2016; Costantini et al. 2018; Ferguson et al. 2018). However, isotopic Bayesian mixing models quantify interspecific interactions as the proportional contribution of each prey to the predator’s diet, while they do not provide information on the biomass and/or number of individuals subtracted to prey populations by predators. This represents a crucial limitation when the food web description has to be used to quantify the effect of invasive species on (1) the population dynamics of other species (Ferguson et al. 2018), (2) food web resilience to perturbations (May 1974; Allesina and Tang 2012; Landi et al. 2018), and (3) potential economic losses associated to the reduction of commercially exploited species.

To fill these gaps, we proposed a novel approach for the quantification of trophic interaction strengths in terms of number of individuals and biomass that each predator and/or competitor subtracts to other species in invaded food webs. Based on abundance, biomass and stable isotope data of species, the proposed method allowed us to calculate the resistance against an invasive species at the population and the food web levels, as well as the impact of the invader on the remaining populations. The method also allowed us to estimate the carrying capacity of fish populations and, thus, to calculate food web resilience to perturbations (May 1974; Allesina and Tang 2012).

As a case study, we considered the invasion of lake food webs by the largemouth bass, Micropterus salmoides (Lacépède) (Costantini et al. 2018), one of the 100 most invasive species in the world (Welcomme 1992; Brown et al. 2009). We compared two communities invaded by the bass and including both autochthonous and allochthonous fish species introduced into the lake before M. salmoides. The two food webs differed in the number of species and trophic links, and we related differences in the impact of the invasive species to their structures. Specifically, we calculated the consumptive and competitive resistance by competitors and predators to the invader, and the biomass that it subtracted to each prey. This also allowed to quantify the potential economic loss associated to the impact of the invader on lake fish stocks, and to simulate the effect of a reduction in its abundance on food web resilience. While we have focused on lake food webs, the proposed approach can be applied to any other habitat and animal species if biomass and diet data (either obtained through stable isotopes or other methods) can be obtained. This virtually includes all the invertebrate and vertebrate animal taxa.

Materials and methods

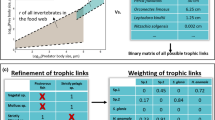

Interspecific interaction strengths and biotic resistance to an invasive species

Using food web data from Costantini et al. (2018), we calculated the strength of all species-pair trophic interactions in the food web. Species’ diets were assessed through Bayesian mixing models (SIAR package for R software) based on stable isotope analysis of fish species and their potential food sources. Abundance and biomass of fish were also measured (Appendix S1: Table S1). Analytical methods for the description of species’ diet in food webs based on isotopic data have been widely addressed and implemented in recent years, and details can be found in Costantini et al. (2018), Rossi et al. (2019), and in the literature cited therein.

Competition

Following Levins (1968) and Calizza et al. (2017), the strength of interspecific competition between species pairs was calculated with reference to the overlap in resource use, accounting for the proportional contribution of each prey to the diet of each predator. Competition strength is indicated by αij, i.e. the effect of species j on species i, in accordance with the Levins’s formula:

where pih and pjh are the proportional consumptions of a resource h by species i and species j respectively.

The strength of interspecific competition was corrected for the biomass ratio between competitors, i.e., the measured value of αij was multiplied for the ratio between the mean body mass of species j and that of species i. Such product will be identified with βij, intending the competitive effect of species j on species i. This was necessary because competition is expected to decrease with increasing difference in body mass between competitors, i.e. the smaller a competitor j with respect to a species i, the weaker the effect of j on i, due to mass-related differences in energetic requirements, food-size selection and foraging habitat exploration (Basset 1995; Emmerson and Raffaelli 2004; Brose et al. 2006; Neutel et al. 2007). This also has the potential to create asymmetric competition for similar values of α due to body mass differences between species.

Then, the limiting effect of a given competitor j on a species i was calculated as:

where Nj is the number of individuals of species j (Calizza et al. 2017 and literature cited therein). According to Eqs. 1 and 2, both αii and βii (i.e. the intraspecific interaction terms) give always 1. Thus, the intraspecific limiting effect is directly dependent on the population size, i.e. the number of individuals (N) of species i.

Predation

The effect of a predator species on its prey species was also calculated. To achieve this, the biomass density of each predator species (BDP) was calculated as:

where NP and BP are the mean density and body mass of a given predator P respectively. Then, the biomass of a given prey m subtracted by a given predator P (BmP) was estimated as:

where FmP is the proportional contribution of the prey to the diet of a predator, and Eff is the efficiency of transformation of prey biomass into predator biomass, with Eff varying between 0 and 1 (see below).

Then, the number of individuals of a prey m subtracted by a predator P (NmP) was obtained as:

where Bm is the mean body mass of the prey.

Carrying capacity and biotic resistance against the invasive species

Based on Eqs. 2 and 5, the carrying capacity of a given species i (Ki) was thus calculated with reference to Lotka-Volterra models (Cohen et al. 1990; Zeeman 1995; Calizza et al. 2017), as:

where βijNj and NmP are the effects of competitors and predators of species i respectively, as reported above, and C and S are the numbers of competitors and predators of species i.

After the calculation of its K, food web-scale competitive and consumptive resistance against an invasive species can be obtained as:

Hence, resistance to an invasive species is measured as the percentage of individuals that competitors and predators subtract to its population with respect to its carrying capacity.

Table S2 in Appendix 1 includes all the variables used in Eqs. 1 to 9, their units and ecological meaning.

Food web structure and resilience to perturbations

Food webs were described with reference to: the number of species (S), the number of feeding links (L), connectance (Cmin), measured as 2L/(S x (S−1)), and connectivity, measured as S x Cmin. The Shannon diversity (Hs) was used to quantifying the diversity of fish communities excluding the invasive species M. salmoides. A bootstrap procedure, available in the Past 3.0 software, was applied to compare Hs values between food webs.

In order to account for the effects of both direct and indirect interactions between species, food web resilience to perturbations (i.e., the local Lyapunov stability) was investigated with reference to the inverse of the classical Jacobian matrix (J−1) (May 1974; Montoya et al. 2009; Calizza et al. 2017). Here, we focused on competitive interactions because they represented the majority of interactions between fish species (Costantini et al. 2018), they have a strong destabilising effect on species assemblages (Allesina and Tang 2012) and because invaders are expected to have strong competitive effects in invaded communities (Marchetti et al. 2004; Gozlan et al. 2010). The classical Jacobian matrix (J) is obtained by multiplying species densities with the interspecific interaction matrix containing pair-wise interaction coefficients (see Appendix 1: Fig. S1 for details). The diagonal of the Jacobian matrix contains the intraspecific interaction terms. The inverse Jacobian matrix (J−1) is obtained by multiplying J for its transpose matrix (J'). Each element of J−1 describes the net effect of species A on species B, taking into account all indirect pathways that link species A and B via intermediate species (Montoya et al. 2009). This implies that species A may have an effect on species B even if the two species do not interact directly. The stability of a given n-species matrix can be inferred from its eigenvalues, with stability (i.e. resilience) being expected for matrices having only negative eigenvalues (in their real part) (May 1974; Allesina and Tang 2012). Here, stability is defined by Re(λmax) of J−1, which is the real part of the maximum eigenvalue, and by its sign. The system will return to the equilibrium for negative Re(λmax), while it will move away from the equilibrium for positive Re(λmax). In both cases, the rate of return to or ‘escape’ from the equilibrium is defined by the absolute value of Re(λmax). The mean real part of all eigenvalues of the matrix, Re(λmean), is a function of the mean diagonal elements of the matrix itself. Increasing the absolute value of the negative terms on the diagonal moves the Re(λmean) towards more negative values (Johnson et al. 2014; Jacquet et al. 2016). Given that the diagonal contains the intraspecific interaction terms, and according to the stability criterion applied, i.e. Re(λmax) < 0, the value of Re(λmax) (hereafter referred to as λ) can thus be seen as a measure of the intraspecific regulation that is needed to stabilize the system considering both direct and indirect interactions between species in the food web.

Application to a case study: fish invasion in lake food webs

Study area and sampling activities

Lake Bracciano is located 32 km north-west of Rome (Lazio, Italy), and it is an oligo-mesotrophic volcanic lake (Rossi et al. 2010). It has a perimeter of 31.5 km, a surface area of 57 km2 and its maximum depth is 165 m. Bass invasion (i.e. Micropterus salmoides) was first reported in 1998 (Marinelli et al. 2007).

Two sampling locations were selected in the north-western (hereafter: North) and south-eastern (hereafter: South) littoral areas of the lake. The South location was characterised by a gently sloping bottom, in contrast to the sharper slope observed in North. Previous samplings along 100 m linear transects indicated that the coverage and diversity of both riparian and submerged vegetation were nearly double on gently sloping bottom (Rossi et al. 2010; Costantini et al. 2018). Accordingly, we considered the North and South locations to be characterised by low and high habitat complexity respectively. Consistently, the percentage of organic matter in sediment (2.2 ± 0.2% in North vs. 17.3 ± 4.2% in South) and macroinvertebrate density were higher in South (311.4 ± 34.9 individuals per sampling site in North vs. 711.9 ± 123.8 in South) (Costantini et al. 2018). In both locations, measured temperature, pH and oxygen concentrations fall within the optimal range for the growth and activity of M. salmoides (Scott and Crossman 1973; Brown et al. 2009; Costantini et al. 2018). Fish were sampled with the help of professional fishermen from local cooperatives. Catches were performed for three days in each location, in the last week of June. A modified version of a surrounding net without a purse line (40 m linear length) and two fishing traps were used in each location and at each sampling occasion. A very fine mesh (0.5 cm) was used in order to include small fish specimens in the catches. Sampling locations and sampling activities are described in detail in Costantini et al. (2018).

Based on a recent checklist of the Italian freshwater fish fauna (Lorenzoni et al. 2019), fish species were indicated as “autochthonous” or “allochthonous”, intending those allochthonous species introduced in central Italy in the past (i.e. before the half of the twentieth century) that naturally persist within the lake (Fig. 1 and Appendix 1: Table S1).

Panels a–b: Biotic resistance of fish communities against the invasive species Micropterus salmoides in the North and South littoral area of Lake Bracciano (Italy). Arrow width is proportional to the limiting effect, measured in terms of number of individuals subtracted to M. salmoides (limiting effects < 1 are excluded). Grey arrows: competition; black arrows: both competition and predation contributed to the limitation on M. salmoides. Panels c–d: Impact of M. salmoides on invaded communities. Arrow width is proportioanl to the estimated biomass that M. salmoides subtracted to each prey. Nodes’ size is proportional to the biomass density of each population. The size of nodes symbolising invertebrates is not to scale with fish. Asterisks denote allochthonous fish species. Dark grey nodes: species found in both locations; light grey nodes: species found only in South. See Tables S1 and S4 in Appendix 1 for details

Impact of Micropterus salmoides on lake fish stocks and food web resilience

Original of North America, M. salmoides is a successful invader worldwide (Brown et al. 2009), producing severe impacts on biodiversity and ecosystem functioning in invaded habitats (Jackson 2002; Leunda 2010; Ribeiro and Leunda 2012). The bass can survive between 10 °C and 32 °C, while optimal temperature ranges from 24 to 30 °C. It normally inhabits waters with an oxygen concentration > 3.0 mg/l, while a concentration between 1.5 mg/l and 3.0 mg/l can be tolerated at optimal temperature. Optimal pH ranges from 6.5 to 8.9 (Scott and Crossman 1973; Brown et al. 2009). Regarding its diet, M. salmoides is known to feed both on invertebrate and fish prey. The bass starts consuming fish when it reaches a standard length of 7–10 cm (Olson 1996; Marinelli et al. 2007), and it is able to adapt its diet depending on habitat complexity and prey availability (Brown et al. 2009; Britton et al. 2010; Costantini et al. 2018).

Various studies provided detailed measurements of physiological parameters of M. salmoides. Specifically, an ingestion rate of 3.0% (range: 2.2–3.9%) of its body mass per day, and an efficiency of prey transformation into body mass (Eff) of 27–28% have been reported (Markus 1932; Hunt 1960; Scott and Crossman 1973; Brown et al. 2009). Together, these values allow estimating that a complete turnover of a given standing biomass of M. salmoides would take 121.4 days (min: 95.0 days, max: 168.3 days, based on the reported range of ingestion rate). This implies a biomass turnover rate (TO) of 3.0 per year on average (range: 2.3–3.7 per year).

Given the TO of M. salmoides, we estimated the year-round body mass that M. salmoides subtracted to each prey population m at each location as:

where BmP is the biomass subtracted to each prey as calculated with Eq. (4). The calculation was repeated by accounting for the different number of specimens of M. salmoides captured at each sampling occasion and location.

For Perca fluviatilis and Atherina boyeri, the two most commercialized fish species of the lake, the biomass subtracted by M. salmoides was converted into economic value by considering a cost of 18 € Kg−1 for the former, and 6 € Kg−1 for the latter in accordance with the local fish market.

M. salmoides was preyed by Perca fluviatilis and Esox lucius only in North. Here, the three species shared a very similar trophic position, having a mainly piscivorous diet (Costantini et al. 2018). P. fluviatilis had a nearly complete overlap in resource use with M. salmoides. In parallel, while E. lucius had a relatively different use of specific prey, the applied Eff falls within values reported for this species (Diana 1983). Accordingly, Eff = 0.27 (known for M. salmoides) was applied also to P. fluviatilis and E. lucius to quantifying the biomass and number of individuals of M. salmoides subtracted by the two predators.

In order to test the effect of M. salmoides on food web resilience, we simulated a progressive reduction in its abundance up to eradication. Based on Lotka-Volterra population models, at each step, the equilibrium abundances of all remaining fish species were recalculated by taking into account the number of individuals of M. salmoides eliminated, and the number of individuals that it subtracted to each competitor (Eq. 2) and/or prey according to the contribution to the diet of M. salmoides (Eq. 5). Then, the value of λ was recalculated.

To explore the effect of increased fish diversity, i.e. increased evenness of fish populations’ abundances, on food web resilience, we repeated the above-mentioned simulations by considering an equal abundance of fish species while maintaining stable the overall number of fish specimens sampled at each location. This had the effect to maximize the evenness of fish populations and thus the Shannon diversity value (Hs) of the two fish communities. This allowed us to evaluate (1) the potential effect of lake management strategies aimed at improving fish diversity, and (2) the theoretical effect of diversity on the resilience of invaded food webs.

Lastly, based on the observed relation between the abundance of M. salmoides and the value of λ, we used linear models to calculate the increase of M. salmoides (as % of the observed abundance within each food web) which should be expected to destabilize the food web (i.e. which led to λ ≥ 0). The Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) was used to select the best model of fit.

Results

Food web structure and biotic resistance against M. salmoides

Richness, abundance and diversity of fish species were all higher in South than in North (Table 1 and Appendix 1: Table S1). Accordingly, the total number of trophic links and food web connectivity were both higher in the former location (Table 1). In contrast, M. salmoides was more abundant in North (45 ± 7 vs. 18 ± 2 individuals, t-test, t = 6.9, p < 0.01). Excluding M. salmoides, 3 autochthonous and 3 allochthonous fish species were found in North, while 7 autochthonous and 6 allochthonous species were found in South. Allochthonous species represented the 79.9% of all the individuals sampled in North and the 40.4% in South (χ2 test, χ2 = 45.1, p < 0.0001), and their mean body mass was generally higher than that of autochthonous species (Appendix 1: Table S1).

The contribution of fish prey to the diet of M. salmoides was higher in North (87% vs. 41% of diet). In particular, P. fluviatilis and A. boyeri constituted the 23% and 43% of its diet respectively in North, while they were not consumed in South (Fig. 1). In turn, M. salmoides contributed to the diet of P. fluviatilis (26%) and E. lucius (7%) in the former location, while it was not preyed in the latter (Fig. 1). Given the low biomass density of P. fluviatilis and E. lucius with respect to M. salmoides (Fig. 1), and the relatively low contribution of M. salmoides to their diet, varying the Eff value had a largely negligible effect on the estimated number of individuals of M. salmoides subtracted by the two predators (Appendix 1: Table S3).

Mean competition strength (i.e. αij) suffered by M. salmoides from the other fish species was higher in South (0.71 ± 0.06 vs. 0.34 ± 0.04, t-test, t = 3.2, p < 0.01) (Appendix 1: Table S4), and the biotic resistance against the invader was higher in this location (Fig. 2). Indeed, the observed abundance of M. salmoides represented the 54.1% of its carrying capacity (K) in North and the 20.3% in South (χ2 test, χ2 = 20.5, p < 0.0001). Competitive resistance was the main component of biotic resistance in North, and it was the only component observed in South (Fig. 2). Here, resistance against M. salmoides was mainly dependent on those species found in this location only (Fig. 2). The top predator P. fluviatilis in North, and the whitefish Coregonus lavaretus in South, were the two species that most limited the invader (Fig. 1). In both locations, allochthonous species had a stronger limiting effect than autochthonous ones on M. salmoides (Fig. 2, North, χ2 = 13.6, p < 0.001; South, χ2 = 10.3, p < 0.01).

Abundance of Micropterus salmoides, as well as the biotic resistance (i.e. the limiting effect, in terms of n° of individuals as a percentage of its carrying capacity) undergone by the bass in the North and South littoral area in Lake Bracciano (Italy). “Common” refer to the biotic resistance by fish species found in both locations; “Only in South” refers to the biotic resistance by fish species found only in South. P and C refer to the effect of predation and competition respectively. Only competition was observed in South. Numbers within each area represent the percentage of the total, while numbers on the right of brackets quantify the n° of individuals subtracted to M. salmoides. The total number of specimens (i.e. the bar height) is the estimated carrying capacity (K) of M. salmoides. The n° of individuals subtracted to M. salmoides by autochthonous and allochthonous fish species (and the percentage on its K) is shown below the two bars

Ecological and economic impact of M. salmoides

Based on our sampling effort (i.e. on the standing biomass density of M. salmoides sampled), the biomass subtracted by M. salmoides to fish prey was markedly higher in North (North: 19.8 ± 0.7 kg vs. South: 3.4 ± 0.2 kg), while that subtracted to macroinvertebrates was higher in South (North: 3.1 ± 0.3 kg vs. South: 5.6 ± 0.3 kg) (Fig. 1 and Appendix 1: Table S4). The two most impacted fish species were P. fluviatilis and A. boyeri (Fig. 1 and Table 2). Both predation and competition contributed to the impact of M. salmoides on P. fluvaitlis in North, while only competition (at a reduced level) contributed in South (Table 2). Predation in North represented the main cause of impact of M. salmoides on A. boyeri (Table 2).

Given the estimated biomass turn-over rate (TO) of M. salmoides and an economic value of 18 € Kg−1 and 6 € Kg−1 for P. fluviatilis and A. boyeri respectively, it is thus possible to estimate that the biomass subtracted by the invader was equivalent to a potential economic loss of 688.2 ± 21.6 € per year and 144.9 ± 10.2 € per year in North and South respectively (Table 2). All individuals of M. salmoides were captured with the linear net (40 m in length), and no individuals were found in fish traps. By standardizing the measured impact over 100-m shoreline, it is thus possible to estimate a potential loss of 1720.5 ± 53.7 € 100 m−1 per year in North and 362.1 ± 25.5 € 100 m−1 per year in South due to the impact of M. salmoides on P. fluviatilis and A. boyeri.

Food web resilience and simulated eradication of the invasive species

The observed value of λ was comprised between − 0.82 (South) and − 0.77 (North) (Fig. 3). Increased resilience (i.e. decreased expected time of recovery after a perturbation, for increased absolute value of λ) was observed when simulating the eradication of M. salmoides, as well as when simulating a more even distribution of abundances among fish populations (Fig. 3 and Appendix 1: Fig. S2). The tight correlation between the relative abundance of M. salmoides and λ allowed to calculate the increase of M. salmoides (as % of the observed abundance) which should be expected to destabilize the food web (i.e. which led to λ ≥ 0) (Appendix 1: Fig. S2). Such threshold value was higher in North (+ 152%) than in South (+ 88%) (χ2 = 50.5, p < 0.0001), and increased to + 365% (North, χ2 = 24.2, p < 0.0001) and + 199% (South, χ2 = 50.5, p < 0.0001) when simulating a more even distribution of abundances among fish populations (Appendix 1: Fig. S2).

Impact of M. salmoides on food web resilience to perturbations. Resilience is expected for negative real values of the maximum eigenvalue, Re(λmax) of the inverse Jacobian matrix. “Obs. North” and “Obs. South” point to the two values of Re(λmax) measured for the food web in the North and South location of Lake Bracciano, based on the observed abundance of M. salmoides at each location. “Max Evenness” (diamonds) refers to the values of Re(λmax) expected under simulated conditions of equal abundances of all fish populations in the food web except M. salmoides, which was maintained at the observed abundance. For each food web, a gradual reduction in the abundance of M. salmoides was simulated and values of Re(λmax) were recalculated accordingly (symbols from − 10% to − 100% of simulated reduction of M. salmoides). Empty symbols: North; Black symbols: South

Discussion

Based on abundance, biomass and diet data of species, we proposed a method for quantifying trophic interaction strengths in terms of number of individuals and biomass that each species subtracts to the others through competition and/or predation in invaded food webs. In our study case, this method was useful to measure the impact of an invasive fish species on the invaded communities, as well as the biotic resistance to the invader. Specifically, our approach allowed us to quantify (1) the ecological and economic impact of the invasive species, considering its effect both on commercial fish stocks and on food web resilience, and (2) the competitive and consumptive resistance of autochthonous and allochthonous fish species. This kind of information can provide an ecological theory-based support to the management and conservation of invaded ecosystems.

The knowledge of the ingestion rate and prey transformation efficiency by the invasive species allowed us to estimate the biomass that it subtracted to each prey. Furthermore, the effect of competition on the invader by autochthonous fish species was weighed according to interspecific differences in body mass. This implies that a competitor smaller than the invader will have a small limiting effect on its abundance, regardless of the similarity of resources used by the two species, as expected by ecological theory, model and empirical evidence (Basset 1995; Emmerson and Raffaelli 2004; Brose et al. 2006; Neutel et al. 2007). While ingestion rates and efficiency of prey transformation into body mass of M. salmoides were available, this may not be the case for other species. Since metabolic and tissue turnover rates are related to the body mass of organisms (Peter 1983; Brown et al. 2004; Vander Zanden et al. 2015), published allometric coefficients may be used to estimate the parameters starting from body mass data. Noteworthy, the efficiency of prey transformation into body mass is the only metabolic parameter necessary to quantify the impact of a predator on its prey according to the proposed method. It may be calculated as the ratio between the amount of food provided and the net increase in weight of a consumer.

Biotic resistance to Micropterus salmoides

Starting from the realized trophic links in the food web, we quantified all the competitive and predatory interactions that limited the invader. In both food webs, competitive resistance had a stronger limiting effect on M. salmoides than consumptive resistance. The latter was only observed in the less complex food web. Here, lower habitat complexity and invertebrate prey availability may have increased the predation of M. salmoides by other predatory fish (Costantini et al. 2018). Notably, the fish species present only in the more complex and species-rich food web provided an important contribution to the higher competitive resistance observed. This supports a positive relation between species richness and community resistance to invasion, consistently with theory and field observations (e.g. Stachowicz et al. 1999; Kennedy et al. 2002). Increased fish abundance and species richness were associated to higher habitat complexity, as often observed in freshwaters (Willis et al. 2005; Smokorowski and Pratt 2007; Thomas and Cunha 2010). Thus, our results suggest a bottom-up effect of habitat features on the invasibility of lake communities. In parallel, recent modelling and field food web studies have demonstrated that increased food web complexity may decrease communities’ invasibility (Hui et al. 2016; Smith-Ramesh et al. 2017; Romanuk et al. 2017). This was ascribed to a higher probability of an invader to undergo competition in highly interconnected webs, as it was observed in our study.

Our approach allowed us also to rank fish species according to their ability to limit the invader that can be considered in biological control strategies. In the study lake, the two species that most limited M. salmoides (P. fluviatilis and C. lavaretus) also represent valuable commercial fish species. This raises management issues since an unavoidable trade-off between the exploitation of these fish species and the maintenance of biotic resistance against the invader exists. Notably, allochthonous species represented half of the fish species sampled and had a strong limiting effect on M. salmoides, particularly at low habitat complexity. This can be explained by their higher abundance, mean body mass and competitive effect, consistently with the expected high adaptability and competitiveness of allochthonous species in non-native habitats. Our data are in line with a recent review of the Italian freshwater fish fauna (Lorenzoni et al. 2019), which found that nearly one out of two species is allochthonous. Thus, our results suggest that the management of invaded ecosystems should carefully consider the ecological role and the potential ecosystem services provided by allochthonous not invasive species.

Impact of Micropetrus salmoides on invaded food webs

High habitat complexity and invertebrate prey availability reduced the impact of M. salmoides, as biomass subtracted to fish with respect to invertebrates, on the invaded fish communities. This may have strong implication in the top-down control exerted by the invader on lower trophic levels (Mancinelli et al. 2007; Jackson et al. 2013). Indeed, comparative lake studies highlighted important effects of bass invasion on native community composition via predation and competition, with cascade effects on local biodiversity (Jackson 2002; Maezono et al. 2005; Leunda 2010) and key ecosystem processes, including the production of fish stocks (Iguchi et al. 2004; Leunda 2010).

While the abundance of invertebrates generally increases with vegetation coverage in freshwaters (Godinho et al. 1994, 1997; Olson et al. 1995; Batzer and Wissinger 1996; Dala-Corte et al. 2020), the higher consumption of invertebrates by M. salmoides in the more complex habitat should not be solely related to their higher abundance. Indeed, the abundance of fish (an energetically richer prey type) increased in a similar manner in this location. According to optimal foraging theory (Pyke et al. 1977; Rossi et al. 2015), we thus hypothesis that the interaction between increased availability of invertebrates and increased energetic cost of fish predation underlies the shift from a fish- to an invertebrate-dominated diet by M. salmoides in the more complex habitat. Consistently, reduced consumption of fish with increasing habitat complexity due to reduced attack success rate (Gotceitas and Colgan 1989), increased handling time of fish prey (Alexander et al. 2015), modification of habitat use by fish prey (Jackson 2002) and increased invertebrate abundance (Godinho et al. 1994, 1997) has been reported for M. salmoides as well as for other invasive fish (Moyle and Light 1996; MacRae and Jackson 2001; Nasmith et al. 2010; Hanisch et al. 2012). The results presented in this case study may thus provide useful information for the management of habitats invaded by alien predatory fish and by M. salmoides in particular, which represents a worldwide ecological and management issue (Welcomme 1992; Jackson 2002).

In the study lake, the measured impact of M. salmoides on other fish species has important economic implications. Indeed, the two most profitable commercial fish in the lake (P. fluviatilis and A. boyeri) were also the two most impacted fish species, and local professional fishermen reported drops in catches following invasion by the bass. Our approach made it possible to estimate the impact of M. salmoides on these two species over a year-round basis. Although our estimations assume no changes in the relative importance of prey to the diet of M. salmoides over the year, they are based on the description of diet composition over a medium-long term period (4–5 months) thanks to the stable isotope analysis of fish muscle (Weidel et al. 2011; Winter et al. 2019). The difference in the potential economic loss observed between locations (~ 1360 € 100 m−1 per year) may thus be considered a useful measure to quantifying the specific ecosystem service provided thanks to the presence of a biodiverse and complex food web.

Scaling from the population- to the food web-level, we quantified the expected resilience to perturbations of invaded communities. To our knowledge, this is the first attempt to quantify food web resilience, as firstly proposed by May (1974), starting from the isotope-based description of realized trophic links between species. Notably, observed values of λ lie in the range expected for real and model ecological networks (Allesina and Tang 2012), implying that resilience after a perturbation can be expected in both food webs, but at a relatively slow rate of recovery (i.e. λ was negative but relatively close to 0).

Simulated eradication of M. salmoides led to increased resilience. In parallel, increased evenness in the abundances of populations also led to increased resilience, and our simulations showed that increased evenness was associated to a higher potential of invaded food webs to maintain stability at high density of M. salmoides. The stability criterion applied (i.e. λ < 0) implies that food web resilience is achieved if all the populations can be expected to recover following a perturbation (May 1974; Allesina and Tang 2012). The differences between simulated (i.e. increased evenness) and observed communities may be explained by considering that under observed conditions poorly abundant species may experience weak intraspecific regulation and thus local extinction after a perturbation due to interspecific competition (Arnoldi et al. 2016). This can also explain the observed slighter increase in the value of λ in South at simulated low abundances of M. salmoides, given the strong interspecific competition suffered by the bass in this location.

The successful eradication of M. salmoides has been reported in small and well-defined habitats, e.g. ponds (Tsunoda et al. 2010) and streams (Ellender et al. 2015), while it is often considered unfeasible in large ecosystems (Britton et al. 2011). In Lake Bracciano, M. salmoides is subject to professional and recreational fishing, and the releasing of captured specimens is not allowed. Nevertheless, this is the only method applied for the control of the bass, and its successful eradication from the lake seems unrealistic. In this context, while the simulated eradication of the bass allowed us to estimate its effect on the stability of invaded food webs, the proposed approach may allow to estimate the economic and ecological impact of M. salmoides at progressively reduced abundances, thus supporting the identification of science-based thresholds for its regulation.

Concluding remarks

Improvements in the quantification of trophic interaction strengths in real ecosystems represent an important step towards a better understanding of the structure and functioning of invaded and pristine ecological communities. Indeed, theoretical and experimental evidences show that the effects of one species on the population dynamics of others (Levins 1968; Montoya et al. 2009; O’Gorman et al. 2010; Calizza et al. 2017) and key food web properties, including resilience (May 1974; Allesina and Tang 2012), robustness to biodiversity loss (Eklöf et al. 2013), energy transfer (Bellingeri and Bodini 2016), and vulnerability to disturbance propagation (Montoya et al. 2009; Calizza et al. 2019), are tightly related to the strength and distribution of interspecific interactions.

Here, the quantification of trophic interactions in invaded food webs provided important insights into ecological mechanisms behind the ability of autochthonous and allochthonous species to resist invasion by a recently introduced species, as well as on the direct and indirect effects of the invader on ecological communities. Notably, our results provided quantitative evidence supporting the conservation of biodiverse and complex food webs, associated to vegetated and productive littoral lake habitats (Costantini et al. 2018), as a way to mitigate bass invasion, its impact on commercial fish stocks and on food web stability.

Species invasions are increasing worldwide, boosted by human activities and climate change (McClelland et al. 2018; Ricciardi et al. 2017; Frost et al. 2019). In parallel, applications of stable isotopes in food web studies are flourishing, and include an increasing number of taxa and habitats, from small invertebrates to aquatic and terrestrial megafauna, from temperate to polar regions (Vander Zanden et al. 2004, 2015; Fry 2006; Michel et al. 2019; Rossi et al. 2015, 2019; Sporta Caputi et al. 2020). Thus, the proposed approach could be applied to a broad array of ecosystems and species if biomass and diet data (either obtained through stable isotopes or other methods) are available, improving our ability to conserve and manage invaded food webs.

Data availability

Data will be made available on reasonable request.

References

Alexander ME, Kaiser H, Weyl OLF, Dick JTA (2015) Habitat simplification increases the impact of a freshwater invasive fish. Environ Biol Fishes 98:477–486

Allesina MS, Tang S (2012) Stability criteria for complex ecosystems. Nature 483:205–208

Alofs KM, Jackson DA (2014) Meta-analysis suggests biotic resistance in freshwater environments is driven by consumption rather than competition. Ecology 95:3259–3270

Arnoldi JF, Loreau M, Haegeman B (2016) Resilience, reactivity and variability: A mathematical comparison of ecological stability measures. J Theor Biol 389:47–59

Basset A (1995) Body size-related coexistence: an approach through allometric constraints on home-range use. Ecology 76:1027–1035

Batzer DP, Wissinger WSA (1996) Ecology of insect communities in nontidal wetlands. Annu Rev Entomol 41:75–100

Bellingeri M, Bodini A (2016) Food web’s backbones and energy delivery in ecosystems. Oikos 125:586–594

Bond AL, Jardine TD, Hobson KA (2016) Multi-tissue stable-isotope analyses can identify dietary specialization. Methods Ecol Evol 7:1428–1437

Britton JR (2012) Testing strength of biotic resistance against an introduced fish: inter-specific competition or predation through facultative piscivory? PLoS ONE 7:e31707

Britton JR, Harper DM, Oyugi DO, Grey J (2010) The introduced Micropterus salmoides in an equatorial lake: a paradoxical loser in an invasion meltdown scenario? Biol Invasions 12:3439–3448

Britton JR, Gozlan RE, Copp GH (2011) Managing non-native fish in the environment. Fish Fish 12:256–274

Brose U et al (2006) Consumer-resource body-size relationships in natural food webs. Ecology 87:2411–2417

Brown JH, Gillooly JF, Allen AP, Savage VM, West GB (2004) Toward a metabolic theory of ecology. Ecology 85:1771–1789

Brown TG, Runciman B, Pollard S, Grant ADA (2009) Biological synopsis of largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides). Can Manuscr Rep Fish Aquat Sci 2884:1–26

Calizza E, Costantini ML, Careddu G, Rossi L (2017) Effect of habitat degradation on competition, carrying capacity, and species assemblage stability. Ecol Evolut 7:5784–5796

Calizza E, Rossi L, Careddu G, Sporta Caputi S, Costantini ML (2019) Species richness and vulnerability to disturbance propagation in real food webs. Sci Rep 9:19331

Cohen JE, Łuczak T, Newman CM, Zhou ZM (1990) Stochastic structure and nonlinear dynamics of food webs: qualitative stability in a Lotka-Volterra cascade model. Proc Royal Soc Lond B Biol Sci 240:607–627

Corrales X et al (2019) Advances and challenges in modelling the impacts of invasive alien species on aquatic ecosystems. Biol Invasions. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-019-02160-0

Costantini ML et al (2018) The role of alien fish (the centrarchid Micropterus salmoides) in lake food webs highlighted by stable isotope analysis. Freshw Biol 63:1130–1142

Crystal-Ornelas R, Lockwood JL (2020) The ‘known unknowns’ of invasive species impact measurement. Biol Invasions 22:1513–1524

Dala-Corte RB et al (2020) Thresholds of freshwater biodiversity in response to riparian vegetation loss in the Neotropical region. J Appl Ecol 57:1391–1402

Davies GD, Britton JR (2015) Assessing the efficacy and ecology of biocontrol and biomanipulation for managing invasive pest fish. J Appl Ecol 52:1264–1273

Diana JS (1983) An energy budget for northern pike (Esox lucius). Can J Zool 61:1968–1975

Dick JTA et al (2017a) Functional responses can unify invasion ecology. Biol Invasions 19:1667–1672

Dick JTA et al (2017b) Invader Relative Impact Potential: a new metric to understand and predict the ecological impacts of existing, emerging and future invasive alien species. J Appl Ecol 54:1259–1267

Didham RK, Tylianakis JM, Gemmell NJ, Rand TA, Ewers RM (2007) Interactive effects of habitat modification and species invasion on native species decline. Trends Ecol Evol 22:489–496

Dzialowski AR, Lennon JT, Smith VH (2007) Food web structure provides biotic resistance against plankton invasion attempts. Biol Invasions 9:257–267

Eklöf A, Tang S, Allesina S (2013) Secondary extinctions in food webs: a Bayesian network approach. Methods Ecol Evol 4:760–770

Emmerson MC, Raffaelli D (2004) Predator–prey body size, interaction strength and the stability of a real food web. J Anim Ecol 73:399–409

Ellender BR, Woodford DJ, Weyl OLF (2015) The invasibility of small headwater streams by an emerging invader, Clarias gariepinus. Biol Invasions 17:57–61

Ferguson JM, Hopkins JB III, Witteveen BH (2018) Integrating abundance and diet data to improve inferences of food web dynamics. Methods Ecol Evol 9:1581–1591

Frost CM et al (2019) Using network theory to understand and predict biological invasions. Trends Ecol Evol 34:831–843

Fry B (2006) Stable isotope ecology, vol 521. Springer, New York

Gallardo B, Clavero M, Sánchez MI, Vilà M (2016) Global ecological impacts of invasive species in aquatic ecosystems. Glob Change Biol 22:151–163

Godinho FN, Ferreira MT (1994) Diet composition of largemouth black bass, Micropterus salmoides (Lacépéde), in southern Portuguese reservoirs: Its relation to habitat characteristics. Fish Manage Ecol 1:129–137

Godinho FN, Ferreira MT, Corets RV (1997) The environment basis of diet variation in pumpkinseed sunfish, Lepomis gibbosus, and largemouth bass, Micropterus salmoides, along an Iberian river basin. Environ Biol Fishes 50:105–115

Gotceitas V, Colgan P (1989) Predator foraging success and habitat complexity: quantitative test of the threshold hypothesis. Oecologia 80:158–166

Gozlan RE, Britton JR, Cowx I, Copp GH (2010) Current knowledge on non-native freshwater fish introductions. J Fish Biol 76:751–786

Hanisch JR, Tonn WM, Paszkowski CA, Scrimgeour GJ (2012) Complex littoral habitat influences the response of native minnows to stocked trout: Evidence from whole-lake comparisons and experimental predator enclosures. Can J Fish Aquat Sci 69:273–281

Hui C, Richardson DM, Landi P, Minoarivelo HO, Garnas J, Roy HE (2016) Defining invasiveness and invasibility in ecological networks. Biol Invasions 18:971–983

Hunt BP (1960) Digestion rate and food consumption of Florida gar, warmouth, and largemouth bass. Trans Am Fish Soc 89:206–211

Iguchi KI et al (2004) Predicting invasions of North American basses in Japan using native range data and a genetic algorithm. Trans Am Fish Soc 133:845–854

Jackson DA (2002) Ecological effects of Micropterus introductions: the dark side of black bass. Am Fish Soc Symp 31:221–232

Jackson MC, Allen R, Pegg J, Britton JR (2013) Do trophic subsidies affect the outcome of introductions of a non-native freshwater fish? Freshw Biol 58:2144–2153

Jacquet C, Moritz C, Morissette L, Legagneux P, Massol F, Archambault P, Gravel D (2016) No complexity–stability relationship in empirical ecosystems. Nat Commun 7:12573

Kennedy TA et al (2002) Biodiversity as a barrier to ecological invasion. Nature 417:636

Kulhanek SA, Ricciardi A, Leung B (2011) Is invasion history a useful tool for predicting the impacts of the world’s worst aquatic invasive species? Ecol Appl 21:189–202

Landi P, Minoarivelo HO, Brännström Å, Hui C, Dieckmann U (2018) Complexity and stability of ecological networks: a review of the theory. Popul Ecol 60:319–345

Latombe et al (2017) A vision for global monitoring of biological invasions. Biol Cons 213:295–308

Laverty C et al (2017) Assessing the ecological impacts of invasive species based on their functional responses and abundances. Biol Invasions 19:1653–1665

Leunda PM (2010) Impacts of non-native fishes on Iberian freshwater ichthyofauna: current knowledge and gaps. Aquat Invasions 5:239–262

Levins R (1968) Evolution in changing environments: Some theoretical explorations. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Lorenzoni M et al (2019) Check-list dell’ittiofauna delle acque dolci italiane. Italian J Freshwat Ichthyol 1:239–254

MacRae PS, Jackson DA (2001) The influence of smallmouth bass (Micropterus dolomieu) predation and habitat complexity on the structure of littoral zone fish assemblages. Can J Fish Aquat Sci 58:342–351

Maezono Y, Kobayashi R, Kusahara M, Miyashita T (2005) Direct and indirect effects of exotic bass and bluegill on exotic and native organisms in farm ponds. Ecol Appl 15:638–650

Mancinelli G, Costantini ML, Rossi L (2007) Top-down control of reed detritus processing in a lake littoral zone: Experimental evidence of a seasonal compensation between fish and invertebrate predation. Int Rev Hydrobiol 92:117–134

Marchetti MP, Moyle PB, Levine R (2004) Invasive species profiling? Exploring the characteristics of non-native fishes across invasion stages in California. Freshw Biol 49:646–661

Marinelli A, Scalici M, Gibertini G (2007) Diet and reproduction of largemouth bass in a recently introduced population, Lake Bracciano (Central Italy). Bulletin Français de la Pêche et de la Pisciculture 385:53–68

Markus HC (1932) The extent to which temperature changes influence food consumption in largemouth bass. Trans Am Fish Soc 62:202–210

May RM (1974) Stability and complexity in model ecosystems. Princeton University Press, Princeton

McClelland GT et al (2018) Climate change leads to increasing population density and impacts of a key island invader. Ecol Appl 28:212–224

Michel LN et al (2019) Increased sea ice cover alters food web structure in east Antarctica. Scientific Reports 9:8062

Montoya JM, Woodward G, Emmerson ME, Solé RV (2009) Press perturbations and indirect effects in real food webs. Ecology 90:2426–2433

Moyle PB, Light T (1996) Biological invasions of fresh water: empirical rules and assembly theory. Biol Cons 78:149–161

Nasmith LE, Tonn WM, Paszkowski CA, Scrimgeour GJ (2010) Effects of stocked trout on native fish communities in boreal foothills lakes. Ecol Freshw Fish 19:279–289

Neutel AM et al (2007) Reconciling complexity with stability in naturally assembling food webs. Nature 449:599-U11

Norbury G, van Overmeire W (2019) Low structural complexity of nonnative grassland habitat exposes prey to higher predation. Ecol Appl 29:e01830

O’Gorman EJ, Jacob U, Jonsson T, Emmerson MC (2010) Interaction strength, food web topology and the relative importance of species in food webs. J Anim Ecol 79:682–692

Olson EJ, Engstrom ES, Doeringsfeld MR, Bellig R (1995) Abundance and distribution of macroinvertebrates in relation to macrophyte communities in a prairie marsh, Swan Lake. Minnesota J Freshwater Ecol 10:325

Olson MH (1996) Ontogenetic niche shifts in largemouth bass: variability and consequences for first year growth. Ecology 77:179–190

Prior KM, Adams DC, Klepzig KD, Hulcr J (2018) When does invasive species removal lead to ecological recovery? Implications for management success. Biol Invasions 20:267–283

Pyke GH, Pulliam HR, Charnov EL (1977) Optimal foraging: a selective review of theory and tests. Q Rev Biol 52:137–154

Ribeiro F, Leunda PM (2012) Non-native fish impacts on Mediterranean freshwater ecosystems: current knowledge and research needs. Fish Manage Ecol 19:142–156

Ricciardi A et al (2017) Invasion science: a horizon scan of emerging challenges and opportunities. Trends Ecol Evol 32:464–474

Romanuk TN, Zhou Y, Valdovinos FS, Martinez ND (2017) Robustness trade-offs in model food webs: invasion probability decreases while invasion consequences increase with connectance. Adv Ecol Res 56:263–291

Rossi L, di Lascio A, Carlino P, Calizza CML (2015) Predator and detritivore niche width helps to explain biocomplexity of experimental detritus-based food webs in four aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems. Ecol Complex 23:14–24

Rossi L et al (2019) Antarctic food web architecture under varying dynamics of sea ice cover. Sci Rep 9:1–13

Rossi L, Costantini ML, Carlino P, di Lascio A, Rossi D (2010) Autochthonous and allochthonous plant contributions to coastal benthic detritus deposits: a dual-stable isotope study in a volcanic lake. Aquat Sci 72:227–236

Schopt Rehage J, Lopez LK, Sih A (2019) A comparison of the establishment success, response to competition, and community impact of invasive and non-invasive Gambusia species. Biol Invasions 22:509–522

Scott WB, Crossman EJ (1973) Freshwater Fishes of Canada. Fisheries Research Board of Canada Bulletin 184. Canadian Department of Fisheries and Oceans, Ottawa

Smith-Ramesh LM, Moore AC, Schmitz OJ (2017) Global synthesis suggests that food web connectance correlates to invasion resistance. Glob Change Biol 23:465–473

Smokorowski KE, Pratt TC (2007) Effect of a change in physical structure and cover on fish and fish habitat in freshwater ecosystems–a review and meta-analysis. Environ Rev 15:15–41

Sporta Caputi S, Careddu G, Calizza E, Fiorentino F, Maccapan D, Rossi L, Costantini ML (2020) Seasonal food web dynamics in the Antarctic benthos of Tethys Bay (Ross Sea): implications for biodiversity persistence under different seasonal sea-ice coverage. Front Marine Sci 7:1046

Stachowicz JJ, Whitlatch RB, Osman RW (1999) Species diversity and invasion resistance in a marine ecosystem. Science 286:1577–1579

Thomaz SM, Cunha ERD (2010) The role of macrophytes in habitat structuring in aquatic ecosystems: methods of measurement, causes and consequences on animal assemblages’ composition and biodiversity. Acta Limnol Bras 22:218–236

Tsunoda H, Mitsuo Y, Ohira M, Senga Y (2010) Change of fish fauna in ponds after eradication of invasive piscivorous largemouth bass, Micropterus salmoides, in north-eastern Japan. Aquatic Conserv Marine Freshwater Ecosyst 20:710–716

Vander Zanden MJ, Olden JD, Thorne JH, Mandrak NE (2004) Predicting occurrences and impacts of smallmouth bass introductions in north temperate lakes. Ecol Appl 14:132–148

Vander Zanden MJ, Clayton MK, Moody EK, Solomon CT, Weidel BC (2015) Stable isotope turnover and half-life in animal tissues: a literature synthesis. PLoS ONE 10:e0116182

Vonesh J, McCoy M, Altwegg R, Landi P, Measey J (2017) Functional responses can’t unify invasion ecology. Biol Invasions 19:1673–1676

Weidel BC, Carpenter SR, Kitchell JF, Vander Zanden MJ (2011) Rates and components of carbon turnover in fish muscle: insights from bioenergetics models and a whole-lake 13C addition. Can J Fish Aquat Sci 68:387–399

Welcomme RL (1992) A history of international introductions of inland aquatic species. ICES Marine Sci Symp 194:3–14

Willis SC, Winemiller KO, Lopez-Fernandez H (2005) Habitat structural complexity and morphological diversity of fish assemblages in a Neotropical floodplain river. Oecologia 142:284–295

Winter ER, Nolan ET, Busst GM, Britton JR (2019) Estimating stable isotope turnover rates of epidermal mucus and dorsal muscle for an omnivorous fish using a diet-switch experiment. Hydrobiologia 828:245–258

Zeeman ML (1995) Extinction in competitive Lotka-Volterra systems. Proc Am Math Soc 123:87–96

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by PNRA-2015/AZ1.01 (M.L. Costantini), PNRA16_00291(L. Rossi), and Sapienza University of Rome, Progetti di Ricerca di Ateneo-RM11916B88AD5D75 (E. Calizza). We thank two anonymous Reviewers for their helpful comments and Jerzy Piotr Kabala for helping us with the collection of bibliographic information on Micropterus salmoides.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Roma La Sapienza within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

E.C., L.R., M.L.C. conceived the study. L.R., M.L.C. provided food web data, E.C., G.C., S.S.C. analysed data. EC, LR, MLC wrote the paper. All Authors revised the paper.

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Calizza, E., Rossi, L., Careddu, G. et al. A novel approach to quantifying trophic interaction strengths and impact of invasive species in food webs. Biol Invasions 23, 2093–2107 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-021-02490-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-021-02490-y