Abstract

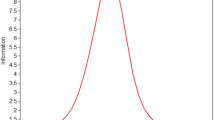

Childhood is a developmental period associated with high risk of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Available validated pencil-and-paper diagnostic tools can be difficult for younger children to engage with given format and length. This study investigated psychometric properties of a briefer, more interactive game version of the Child PTSD Symptom Scale for DSM-5 (CPSS-5). Participants (n = 49) were children attending primary care appointments between 8 to 12 years of age who were exposed to a DSM-5 Criterion A trauma. Participants completed the 6-item screening version of the CPSS-5 delivered in mobile tablet game format (the CPSS-5 Screen Team Game) and a self-report version of the full CPSS-5 (CPSS-5-SR) before their medical appointments. The mobile game showed adequate internal consistency (α = 0.79), was significantly positively correlated to the total CPSS-5-SR (r = .74, p < .001, n = 49), and with the total of the six identical items of the CPSS-5-SR (r = .79, p < .001, n = 49), demonstrating good convergent validity. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analyses revealed a cut-off score of 9 on the screening game as indicative of probable PTSD. Implementation of this screening game into primary care settings could be a low-burden method to greatly increase the detection of pediatric PTSD for referral to appropriate integrated care interventions.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Alisic, E., Zalta, A. K., van Wesel, F., Larsen, S. E., Hafstad, G. S., Hassanpour, K., & Smid, G. E. (2014). Rates of post-traumatic stress disorder in trauma-exposed children and adolescents: Meta-analysis. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 204(5), 335–340.

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association.

Anthoine, E., Moret, L., Regnault, A., Sébille, V., & Hardouin, J. B. (2014). Sample size used to validate a scale: A review of publications on newly-developed patient reported outcomes measures. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 12, 1–10.

Baranowski, T., Blumberg, F., Buday, R., DeSmet, A., Fiellin, L. E., et al. (2016). Games for health for children—Current status and needed research. Games for health journal, 5(1), 1–12.

Brewin, C. R., Rose, S., Andrews, B., Green, J., Tata, P., McEvedy, C., et al. (2002). Brief screening instrument for post-traumatic stress disorder. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 181(2), 158–162.

Brown, J. D., & Wissow, L. S. (2010). Screening to identify mental health problems in pediatric primary care: Considerations for practice. International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine, 40(1), 1–19.

Brown, D. W., Anda, R. A., Tiemeier, H., Felitti, V. J., Edwards, V. J., Croft, J. B., & Giles, W. H. (2009). Adverse childhood experiences and the risk of premature mortality. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 37, 389–396.

Butler, A. M. (2014). Shared decision-making, stigma, and child mental health functioning among families referred for primary care–located mental health services. Families, Systems & Health, 32(1), 116–121.

Carrion, V. G., Weems, C. F., Eliez, S., Patwardhan, A., Brown, W., Ray, R. D., & Reiss, A. L. (2001). Attenuation of frontal asymmetry in pediatric posttraumatic stress disorder. Biological Psychiatry, 50(12), 943–951.

Carrion, V. G., Haas, B. W., Garrett, A., Song, S., & Reiss, A. L. (2009). Reduced hippocampal activity in youth with posttraumatic stress symptoms: An FMRI study. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 35(5), 559–569.

Carrion, V. G., Weems, C. F., Richert, K., Hoffman, B. C., & Reiss, A. L. (2010). Decreased prefrontal cortical volume associated with increased bedtime cortisol in traumatized youth. Biological Psychiatry, 68(5), 491–493.

De Bellis, M. D., Hooper, S. R., Spratt, E. G., & Woolley, D. P. (2009). Neuropsychological findings in childhood neglect and their relationships to pediatric PTSD. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society, 15(6), 868–878.

Flannery, D. J., Singer, M. I., & Wester, K. (2001). Violence exposure, psychological trauma, and suicide risk in a community sample of dangerously violent adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 40(4), 435–442.

Foa, E. B., Johnson, K. M., Feeny, N. C., & Treadwell, K. R. (2001). The child PTSD symptom scale: A preliminary examination of its psychometric properties. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 30(3), 376–384.

Foa, E. B., Asnaani, A., Zang, Y., Capaldi, S., & Yeh, R. (2018). Psychometrics of the child PTSD symptom scale for DSM-5 for trauma-exposed children and adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 47(1), 38–46.

Gonzalez, A., Monzon, N., Solis, D., Jaycox, L., & Langley, A. K. (2016). Trauma exposure in elementary school children: Description of screening procedures, level of exposure, and posttraumatic stress symptoms. School Mental Health: A Multidisciplinary Research and Practice Journal, 8(1), 77–88.

Kemmis-Riggs, J., Dickes, A., & McAloon, J. (2017). Program components of psychosocial interventions in foster and kinship care: A systematic review. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 1, 13–40.

Kessler, R. C., Petukhova, M., Sampson, N. A., Zaslavsky, A. M., & Wittchen, H. U. (2012). Twelve-month and lifetime prevalence and lifetime morbid risk of anxiety and mood disorders in the United States. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 21(3), 169–184.

Kozlowska, K., & Hanney, L. (2001). An art therapy group for children traumatized by parental violence and separation. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 6(1), 49–78.

Malarbi, S., Abu-Rayya, H. M., Muscara, F., & Stargatt, R. (2017). Neuropsychological functioning of childhood trauma and post-traumatic stress disorder: A meta-analysis. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 72, 68–86.

Mannarino, A. P., Cohen, J. A., Deblinger, E., Runyon, M. K., & Steer, R. A. (2012). Trauma- focused cognitive-behavioral therapy for children: Sustained impact of treatment 6 and 12 months later. Child Maltreatment, 17(3), 231–241.

McKay, K. E., Halperin, J. M., Schwartz, S. T., & Sharma, V. (1994). Developmental analysis of three aspects of information processing: Sustained attention, selective attention, and response organization. Developmental Neuropsychology, 10(2), 121–132.

McLaughlin, K. A., Koenen, K. C., Hill, E. D., Petukhova, M., Sampson, N. A., Zaslavsky, A. M., & Kessler, R. C. (2013). Trauma exposure and posttraumatic stress disorder in a national sample of adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 52(8), 815–830.

Pescosolido, B. A., Perry, B. L., Martin, J. K., McLeod, J. D., & Jensen, P. S. (2007). Stigmatizing attitudes and beliefs about treatment and psychiatric medications for children with mental illness. Psychiatric Services, 58(5), 613–618.

Santiago, C. D., Raviv, T., & Jaycox, L. (2017). Creating healing school communities: School based interventions for students exposed to trauma. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Schaefer, C. E. (1993). In C. E. Schaefer (Ed.), The therapeutic powers of play. Lanham: Jason Aronson.

Steinberg, A. M., Brymer, M. J., Decker, K. B., & Pynoos, R. S. (2004). The University of California at Los Angeles post-traumatic stress disorder reaction index. Current Psychiatry Reports, 6(2), 96–100.

Wissow, L. S., Brown, J., Fothergill, K. E., Gadomski, A., Hacker, K., Salmon, P., & Zelkowitz, R. (2013). Universal mental health screening in pediatric primary care: A systematic review. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 52(11), 1134–1147.

Yule, W. (1992). Post-traumatic stress disorder in child survivors of shipping disasters: The sinking of the ‘Jupiter. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 57(4), 200–205.

Acknowledgements

The authors are very appreciative of the creativity, generosity and talent provided by the graduate students (with support from their faculty mentors) from Carnegie Mellon University who created the CPSS-5 Screen Team Game as part of their graduate training. The authors would also like to express their sincerest appreciation to Hallie Tannahill, the post-baccalaureate research assistant who assisted on the initial set-up of the study and assisted the first author in establishing the recruitment sites and procedures. The authors are also grateful for Savannah Simon and Maham Ahmad, two undergraduate research assistants, who contributed their time to data collection for the study. In addition, the authors would like to thank the following community sites and the support staff, nurses, clinicians and administrators working at these clinics who collaborated on this study by allowing the research staff to come on site to collect the data presented here: Children’s Hospital of Pennsylvania (CHOP) South Philadelphia Primary Care Clinic, CHOP Karabots West Philadelphia Pediatric Care Center, and Joseph J. Peters Institute of Philadelphia. A special thanks to our pediatrics colleagues Dr. Steven Berkowitz, Dr. Kari Draper, and Dr. Terri Behin-Aein for their support and facilitation of the project at the various primary care clinics. Finally, this work could not be done without the participation of the children who were brave enough to share their stories with our research team in order to help other youth who might have undetected PTSD symptoms in primary care settings. We are deeply thankful to each of you.

Funding

This work was primarily funded by the Penn Undergraduate Mentorship Program (PURM) awarded to Dr. Anu Asnaani through the Center for Undergraduate Research and Fellowships. The CPSS-5 Screen Team Game items were derived from a previous psychometric study on the CPSS-5 (PI: Asnaani) that was funded through a Clinical Translational Science Award given by the Community Engagement Action Research (CEAR) Core (8UL1TR000003) at the University of Pennsylvania, also awarded to Dr. Asnaani. The original CPSS-5 measure from which the CPSS-5 Screen Team Game items were derived were devised by Drs. Edna Foa and Sandra Capaldi.

In addition, the idea behind placing the CPSS-5 Screen items into a more interactive, game format was conceived by co-authors Dr. Judith Cohen and Dr. Anthony Mannarino. The final product of the CPSS-5 Screen Team Game was developed through a collaboration between the Center for Traumatic Stress in Children and Adolescents at Allegheny Hospital and the Entertainment Technology Center of Carnegie Mellon University, with support from the Highmark VITAL Program. The CPSS-5 Screen Team Game will be available at no cost from the Apple Store and Google Play.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Standards and Informed Consent

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation at the University of Pennsylvania and the Children’s Hospital of Pennsylvania and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000. Informed consent was obtained from all patients being included in the study.

Disclosure of Interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Asnaani, A., Narine, K., Suzuki, N. et al. An Innovative Mobile Game for Screening of Pediatric PTSD: a Study in Primary Care Settings. Journ Child Adol Trauma 14, 357–366 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40653-020-00300-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40653-020-00300-6