When Philippine President Ferdinand E. Marcos dedicated the Pacific War Memorial (Figure 1) on 22 June 1968, he described it as a “monument to the American and Filipino alliance for freedom.”Footnote 1 The structure, which stands on Corregidor Island in Manila Bay, was particularly significant for an American overseas memorial, as it was built to commemorate the Philippine as well as the American forces that had lost their lives in the Pacific theatre during the Second World War. Yet Marcos's depiction of a partnership belies the anomaly that is the memorial's construction by the United States on a former colony, twenty-two years after it had gained independence. While the United States has built many overseas memorials to commemorate its armed forces,Footnote 2 the Pacific War Memorial stands alone both in its location and its character as “much broader than a ‘Battle Monument’ … It is a symbol to be erected by the people of the United States and given to the people of the Philippines.”Footnote 3 Rather than simply commemorating American achievements in battle, it memorializes a relationship and an imperial legacy that the United States was unwilling to relinquish in the early decades of the Cold War.

Figure 1. Pacific War Memorial, Corregidor, Philippines. Photograph by the author.

Although there has been some mention of the Pacific War Memorial in scholarship on Second World War memorialization, there has been no study of its meaning or of the impetus behind its creation.Footnote 4 Additionally, while several studies have examined the role of Second World War memorialization and its use in Southeast Asian national and regional identity building,Footnote 5 there has been little discussion of the role that United States overseas commemoration has played in this, and to what extent these transnational memorials shape – and are shaped by – the host country's existing and wider remembrances. The aim of this article is to explore the creation of the Pacific War Memorial and the degree to which the United States sought to shape its colonial legacy long after it recognized Philippine independence. Jenny Woodley and Christopher J. Young, in this journal, have noted the tensions that occur within memory construction in other contexts.Footnote 6 Similarly, the Pacific War Memorial and the Corregidor “memoryscape”Footnote 7 were shaped by a multitude of sometimes competing “commemorative agents.”Footnote 8

The Pacific War Memorial's location, Corregidor, marks the last place at which the United States Army Forces in the Far East (USAFFE) surrendered the Philippines to the Imperial Japanese Army during the Second World War. Following the aerial bombardment of Manila on 8 December 1941, the USAFFE, led by General Douglas MacArthur, had withdrawn to the island, as well as to the Bataan peninsula. The forces on Bataan eventually surrendered on 9 April 1942 but those on Corregidor perservered until a month later on 6 May. Corregidor was also a significant site in the recapturing of the Philippines from the Japanese, and was reclaimed by the returning USAFFE in February 1945. The Japanese occupation ended on 5 July 1945 and the Philippines was recognized as an independent nation by the United States on 4 July 1946.

Even whilst exiled to the United States during the war, the Philippine government commemorated the anniversaries of the falls of Bataan and Corregidor. Indeed the names of both locations became synonymous with strength and courage. When paying tribute to a fallen soldier in 1943, Philippine President Quezon declared, “his was unflinching courage, his was loyalty unto death, his story is written in blood, in the forests and hills of Bataan and the rock that is Corregidor.”Footnote 9 Similarly, on his return to the Philippines in 1944 General MacArthur announced, “rally to me. Let the indomitable spirit of Bataan and Corregidor lead on.”Footnote 10 Through this shared symbolic rhetoric, Bataan and Corregidor came to represent an alliance between the United States and the Philippines and were regularly referred to as such. During the 1946 Philippine Independence Day proceedings, American Senator Millard Tydings stated, “Though our governments may sever the political ties which for half a century have bound us together, our governments can never alter or repeal the history of Bataan and Corregidor.”Footnote 11

However, although remembrance served to reinforce the relationship between the two countries, it was also deployed as part of a Philippine nation-building agenda. In 1945, while pushing for immediate independence from the United States, President Osmeña commemorated National Heroes Day at a former Japanese internment camp, asserting that, “like Bataan, Capas also stands for Filipino courage.”Footnote 12 The use of National Heroes Day to remember the Second World War dead places the dead within the Philippine national narrative and elevates them to the status of Philippine revolutionary heroes such as José Rizal and Andres Bonifacio, whose personages were also honoured on this day. National commemoration of Rizal had been legislated under American colonial rule in 1902, with a monument erected in Manila's Luneta Park in 1913.Footnote 13 However, remembrance of Rizal was not simply a colonial institution. The earliest account of Rizal's memorialization was a service that took place in Paco Cemetery, Manila, on 1 November 1898.Footnote 14 Furthermore, Rizal's remembrance had been frequently used as a platform to call for Philippine independence in the early years of United States colonial rule.Footnote 15 Thus, although a culture of shared remembrance between the Philippines and the United States existed, memorialization also served a nationalist purpose.

Veterans’ groups were also involved in memorialization. In 1952 the Defenders of Bataan and Corregidor was formed by Philippine veterans who, like the government, aimed to promote “justice, peace and democracy.”Footnote 16 Yet veterans also had personal motivations to “keep alive the memories of our military service together; to help one another and those whom our deceased brothers-in-arms left behind.”Footnote 17 This manifested itself in their petition to have the anniversary of Bataan's surrender recognized as a national day of commemoration, to which President Quirino agreed in 1952. The veterans’ demand for official recognition of their significant role in the conflict also took place in the aftermath of the 1946 Rescission Act. This Act decreed that Filipinos who had served the United States in the Philippine Army, or as approved guerrillas, were not recognized as having been in active service, thus preventing them from receiving any benefit payments.Footnote 18 Similarly, American veteran groups lobbied the Philippine government to distinguish the anniversary of the victory at Bessang Pass as a national holiday.Footnote 19 Following the institutionalization of Bataan Day, Second World War remembrance became focussed on this date. Indeed, the significance of Bataan as a memorial site to the government was evident immediately following the end of the war when President Osmeña set aside land for a Bataan National Park as part of the official commemorations in 1945.Footnote 20 Ricardo Jose has argued that the Philippine focus on Bataan was due to the large numbers of Filipinos who had fought there, whereas on Corregidor the majority of soldiers had been American.Footnote 21 Thus, before the American government announced its proposal to develop the Pacific War Memorial in 1953, the Philippine Second World War memorial landscape had been shaped significantly, with a notable emphasis on Bataan, indicating a shift from the shared memory of Corregidor. Indeed, although the anniversary of Corregidor's fall was also marked, official remembrances of this event eventually became subsumed within the Bataan Day rites.

In 1953 the United States Congress created the Corregidor–Bataan Memorial Commission (Corregidor Commission), to commence a “study for the survey, location and erection on Corregidor Island of a replica of the Statue of Liberty and the use of Corregidor Island as a memorial to the Philippine and American soldiers, sailors, and marines who lost their lives while serving in the Philippines during World War II.”Footnote 22 The memorial was initiated by former American ambassador to the Philippines Emmet O'Neal, who also served as chairman of the commission. Altogether the Corregidor Commission comprised nine members, including three Senators, three Congressmen, and three citizens: a former marine, a journalist who had been stationed on Corregidor, and O'Neal himself. Although there was no stipulation as to the commission's political composition, seven of its members were Democrats. Yet following the inauguration of President Eisenhower on 20 January 1953 and the Republican majority achieved in the Senate and House of Representatives in the years that followed, the Corregidor Commission's political makeup shifted.Footnote 23 Nevertheless, its agenda remained the same, since the vision for what would become the Pacific War Memorial was very much O'Neal's from the beginning.

The Pacific War Memorial was designed by Seattle-based architectural firm Naramore, Bain, Brady, and Johanson, and comprises a square courtyard, at the centre of which stands a domed room, ringed with reflecting pools. The room is open on all sides and supported by wide rectangular columns. At the centre of the room is a circular altar, above which the sky can be viewed through a rounded opening in the dome. On the other side of the courtyard is a long walkway, walled in by marble tablets listing each of the major battles of the Pacific conflict. Reflecting pools sit on either side of the walkway and the centre contains a rectangular concrete planter, within which local foliage has been planted. The walkway terminates in steps leading up to a raised platform that looks out onto Manila Bay. A bronze sculpture in the shape of a flame sits on the platform. Designed by the Greek American sculptor Aristides Demetrios, it is entitled the Eternal Flame of Freedom.

Using archival sources from the United States and the Philippines relating to the planning and construction of the Pacific War Memorial, as well as a visual interpretation of the monument itself conducted on two site visits, this article explores the tensions between colonial and decolonized remembrance within the site and the wider Corregidor memoryscape. The research for this article was undertaken at the Harry S. Truman Presidential Library and the Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Library. Additional sources were obtained at the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and the Lyndon Baines Johnson Presidential Library. Further research was completed at the American Historical Collection at Ateneo de Manila University, Philippines. In addition, I conducted interviews with Artemio Matibag, the director of the Corregidor Foundation, which manages Corregidor, and with Robert Hudson, the son of an American Second World War veteran, who is involved in the memorialization of the Bataan death march.

The article is divided into three parts. The first discusses the formation of the Corregidor–Bataan Memorial Commission and the significant role of its chairman, Emmet O'Neal, in shaping the development and construction of the memorial. The second analyses the aesthetics of the Pacific War Memorial itself. And the third considers its relationship to the wider memoryscape of Corregidor.

The article illustrates how the United States was still coming to terms with its colonial legacy long after Philippine independence. This imperial agenda perhaps explains why the memorial has not been the focus of studies of United States commemoration overseas, as it contradicts the “contemporary American nationalism” that the American Battle Monuments CommissionFootnote 24 sought to express through its memorializing activities in the years following the Second World War.Footnote 25 The Pacific War Memorial's creation by the Corregidor–Bataan Memorial Commission, a government agency separate from the ABMC, is indicative of this distinctive agenda. Yet the memorial's position within wider Philippine Second World War remembrance indicates that this agenda was often at odds with the objectives of a newly independent country. Understanding the ways in which these multiple motivations and commemorations shaped both the Pacific War Memorial and wider Second World War memorialization can lead to a greater comprehension of how these transnational memoryscapes function within the host nation, and the extent to which they perpetuate a colonial memory, as both the United States and the Philippines sought to establish their place amidst a rapidly decolonizing Asia.

“A SYMBOL TO BE ERECTED BY THE PEOPLE OF THE UNITED STATES”

Writing after his death in 1967, Emmet O'Neal's family commented that it was during his ambassadorship to the Philippines (1947–48) that he had a “vision” for a memorial on Corregidor.Footnote 26 Indeed, following his departure from office, O'Neal retained an active interest in the Philippines and in veterans’ affairs, campaigning for the payment of benefits to Philippine veterans and also seeking to memorialize the Philippine experiences of the Second World War through the publication of Philippine memoirs from the period.Footnote 27 O'Neal believed in the positive impact of American colonial rule on the Philippines, and in the significance of the association of the two countries. He wrote, “There is not found in all the history of the world such a relationship as that of America and the Philippines which resulted in the launching of the Philippines as a sovereign nation.”Footnote 28 This translated into the importance placed on the battles that had been fought by the USAFFE in the Philippines during the Second World War. As O'Neal stated, “we should not wait longer to memorialize the almost unparalleled deed in the Far Eastern Theater.”Footnote 29 He believed not only in the distinction of the United States’ Philippine mission but also in the merit and morality of its role in the Second World War, asserting that “the United States fought primarily to help other nations live as free men.”Footnote 30

These ideas informed O'Neal's vision for a memorial, which initially comprised a replica of the Statue of Liberty. He saw the statue as emblematic both of American achievements in the war and of the historical significance of the country itself. O'Neal wrote, “From Europe the torch of Liberty was handed to America. Now America has an opportunity to hand it on to Asia.”Footnote 31 He perceived the United States as having a momentous role in the progress of civilization. Furthermore, the very concept of installing a replica of the Statue of Liberty suggests that O'Neal's idea of what a memorial could and should be was distinctly Western, specifically East Coast American and European. Indeed the Statue of Liberty, even following its gifting from France, retained a strong association with Europe, as European immigrants would enter the country via Ellis Island on which the statue stands. Thus this reverence for the statue is suggestive of ideals around American national identity, with immigration quotas favouring Europeans until as late as 1965, twelve years after the Corregidor–Bataan Memorial Commission was formed.

Additionally O'Neal responded to calls from both the Philippine and American communities in Manila for a more practical memorial building, such as a theatre or hospital, by articulating the merits of other American memorials. He described those who viewed the Lincoln Memorial and the Washington Monument as “better citizens.”Footnote 32 Furthermore, O'Neal argued that if France had built an opera house instead of the Statue of Liberty, it would have been “obsolete or discarded by this time.”Footnote 33 Not only was the memorial to be American in its genesis and its ideas, then, it was also intended to leave an American legacy, one that O'Neal feared would be forgotten. O'Neal saw the memorial as “much broader than a ‘Battle Monument’ … It is a symbol to be erected by the people of the United States and given to the people of the Philippines.”Footnote 34 This not only hints at O'Neal's broader vision for the memorial but also reflects his perception of the United States as the conduit of civilization's progress. This comment also encapsulates the way in which the Corregidor Commission worked with the Philippine government in the construction of the memorial; from the outset it was always to be an American construct, “given” to the people.

Almost simultaneously with the formation of the Corregidor Commission, in 1954 Philippine President Magsaysay formed a parallel commission entitled the Philippine National Shrines Commission (Philippine Commission). Comprised much like the Corregidor Commission (however, in this case its members were all government officials with no ordinary citizens or veterans represented), it used similar rhetoric to outline its purpose. The Philippine Commission sought to “glorify … the memory and scenes of Philippine–American resistance to aggression and to inspir[e] … the nation as well as the rest of the free world into an unremitting defense of democracy and freedom throughout the ages.”Footnote 35 Thus the Philippine government framed the Second World War in a similar manner to the United States, promoting democracy as a means of fighting communism. Yet this was unsurprising, as, with the help of American forces, President Magsaysay had successfully suppressed the Hukbalahap, a communist resistance movement that had originated during the Japanese occupation and continued, following 1946, to oppose the new Philippine republic.Footnote 36 Likewise, the Philippine Commission had its own agenda and was encouraged to develop plans for its own memorials and monuments “wherever they are deemed desirable.”Footnote 37 Indeed only if the Philippine Commission deemed it “proper” should they “endeavour to bring about an integration of the plans of both bodies [the Corregidor Commission and the Philippine Commission] into a common project.”Footnote 38

While the Philippine Commission pursued its own plans, the Corregidor Commission's objectives had broadened in 1955 from the memorialization of those who had fought in Bataan and Corregidor to the commemoration of “all men who fought under the American flag in the Pacific theater during World War II.”Footnote 39 In their statement outlining the objectives of the memorial, the Corregidor Commission stated that it would work on three levels. First, it would remember the surviving veterans and the families of those who fought and died, recognizing “each man's contribution” to “beating back an aggressor bent on conquest and tyranny.” Second, it would serve as a message to all Filipinos of the United States’ “understanding and appreciation” of the suffering they endured to stand alongside them. Lastly, it would “become a living memorial to encourage the Filipinos and other Oriental nations to work unceasingly in the cause of democracy and freedom.”Footnote 40 Thus the very genesis of the memorial embodied the Cold War rhetoric of democracy versus communism and underscored the necessity of the American and Philippine relationship to a stable world order. Furthermore, the location of a “Pacific” war memorial in the Philippines reinforced the importance of the country to the United States’ position in Asia: the Philippines held the largest United States overseas military bases, and from here American and Philippine troops were sent to Vietnam.

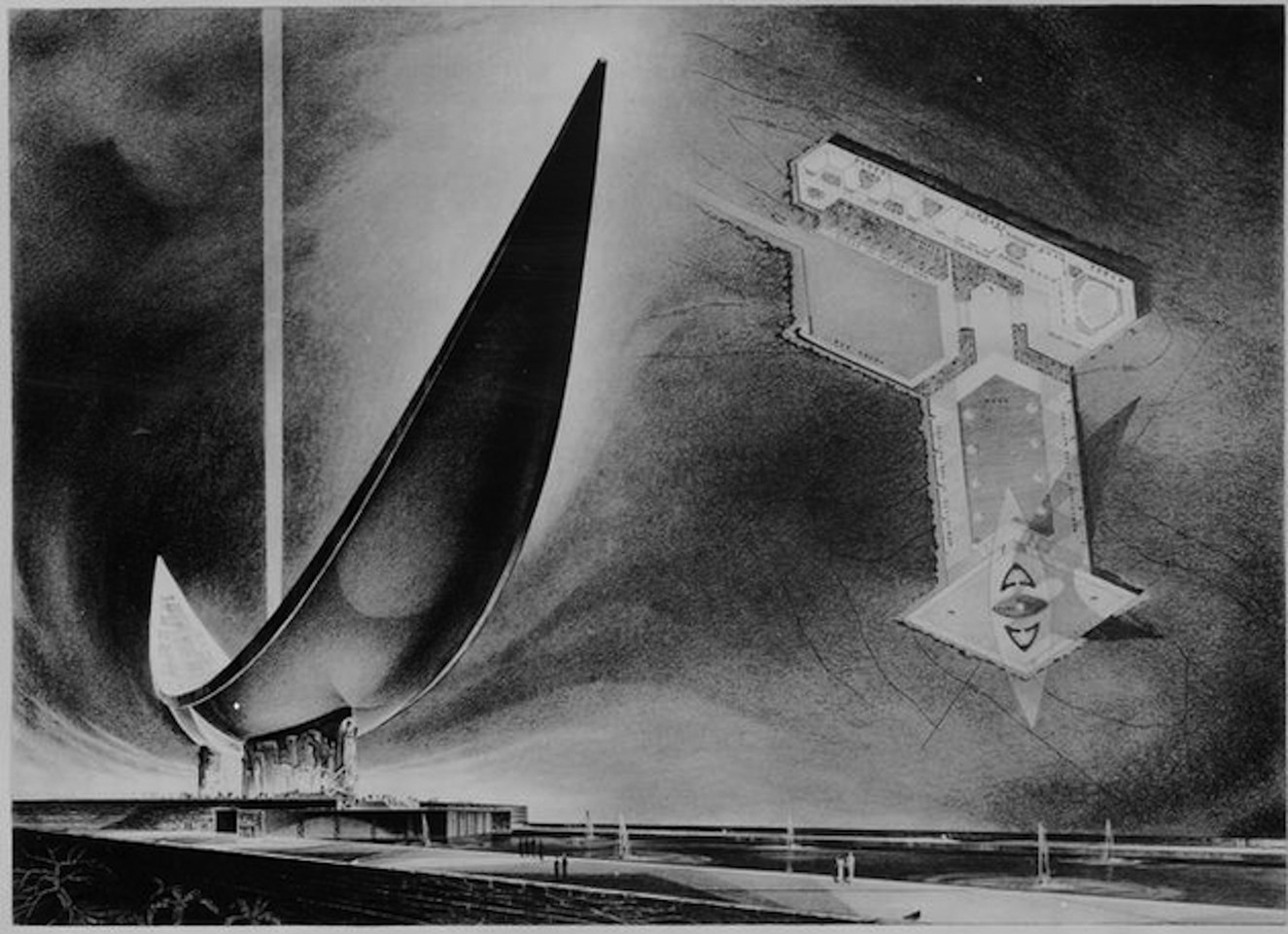

This increased scope had an impact on the form the memorial would take. In 1955 a bill was introduced into Congress amending the original legislation to alter the replica of the Statue of Liberty to a more general “memorial.”Footnote 41 In 1957 the Corregidor Commission ran a nationwide competition (within the United States) in which forty-eight architects competed, with five finalists chosen by a jury of architects. The winning design was then selected by the commission. The winning entry came from Seattle-based architectural firm Naramore, Bain, Brady, and Johanson, and depicted two “uplifted arms”Footnote 42 rising above a “memorial room” (Figure 2).Footnote 43 According to O'Neal the “arms” were intended to “symbolize the East and the West, each a separate and distinct entity, yet each equally striving to the highest point; each held to the other by, [sic] an encircling bond without which the structure of their civilization would collapse without the tie between the two.”Footnote 44 Thus the memorial's composition immediately embodied the agenda of the commission and of O'Neal, and reinforced the American relationship with Asia, of which the Philippines was now perceived as a part.Footnote 45 Yet it also had not lost the imagery of the Statue of Liberty for included in the design was a shaft of light to be emitted between the “arms,” symbolizing “the singleness of purpose, shared by both East and West.”Footnote 46 This alternative torch of liberty distinguishes the Pacific War Memorial from the eternal flame found in traditional war memorials; this was not to be a reminder of the dead but “a form that somehow would express a future, not a past; a hope, and not a sorrow.”Footnote 47 The impact of O'Neal's concept of what a memorial should be is apparent: it should be awe-inspiring and reverential, promoting the civic duty he recognized in the Lincoln Memorial and the Washington Monument. The Pacific War Memorial was not designed to comfort the bereaved, as both Inglis and Edwards have noted in the first memorials erected to the dead of the First and Second World Wars, but to inspire future generations.Footnote 48

Figure 2. Winning entry by Naramore, Bain, Brady, and Johanson, 1957. Courtesy of the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library. Image: White House Central Subject Files, Box 199, Folder 16, 22, JFK Library.

Although the Philippine Commission was not involved in the competition, nor in the final selection, a delegation from the commission was invited to Washington, DC to view the competition finalists in 1957. A letter from its chairman, Eulogio Balao, to O'Neal following the visit confirmed their agreement with the short list but underlined their limited involvement, reiterating that the “selection [was] made by you.”Footnote 49 Nonetheless, Balao attempted to shape the memorial by requesting the incorporation of a design by renowned Philippine artist Guillermo Tolentino.Footnote 50 He noted, too, that this was “the only design submitted from the Philippines,”Footnote 51 implying the little involvement the country had over the project. O'Neal's aim to retain control over the memorial stemmed not only from his desire for it to be an “American” undertaking and thus an American legacy, but also from a colonial mind-set of knowing what would best serve the Philippine people. O'Neal commented that the memorial should appeal to “Oriental forms and tastes as well as Occidental,”Footnote 52 and referenced MacArthur, who believed that any monument built in the Philippines should be on the “showy side” in order to “appeal” to Filipinos.Footnote 53

O'Neal's idea of what Filipinos would “want” translates into his perception of the memorial's audience. In response to criticisms from Philippine newspapers and from the American community in Manila as to the inaccessibility of a memorial on Corregidor, O'Neal argued that the boat trip would be “an asset not a deterrent” as it would constitute part of a day out.Footnote 54 In a similar vein, he asserted that the Philippines was “90.8% Christian which is man's greatest defence against communism.”Footnote 55 Excluding the poor, as well as the Filipino Muslim population and other non-Christian minority communities, O'Neal envisioned an idealized memorial community, comprising relatively affluent Catholic Filipinos, for whom the excursion to the island would be affordable and the memorial's Christian elements appealing. However it was the message rather than the audience that was of ultimate importance. When the Eisenhower administration indicated in 1960 that it would only support a “clean-up” on Corregidor and the erection of a “simple marker and plaque,”Footnote 56 O'Neal's primary concern was the marker's potential perception as a “Filipino accomplishment” as opposed to “an American memorial to the joint sacrifices of brothers-in-arms.”Footnote 57

Despite this, Congressional and White House opposition to O'Neal's “important matter” resulted in long delays to the memorial's authorization and construction.Footnote 58 In 1957 the bill authorising $7.5 million for the project failed to pass the Senate. Congressman Frank Thompson commented on the absence of Philippine involvement, remarking in the House of Representatives, “for some strange reason never made public, the contest was confined entirely to the United States. Filipino artists were not invited to compete in the contest nor invited to act as judges of the contest. In other words, the people of the Philippines were presented with an accomplished fact.”Footnote 59 Thompson went on to criticize the design, commenting that it was perceived in the Philippines as looking like “a pair of carabao horns,” which he implied was derogatory as it symbolized the “working animal of the Philippines.”Footnote 60 There was also financial opposition from the Bureau of the Budget, who in 1958 requested that the administration alter its stance on the funding due to the country operating a budget deficit and the commission's inability to raise money from private sources.Footnote 61 Whilst Edwards has identified “officers of government agencies” as one group of commemorative agents in post-Second World War memorial building in Europe,Footnote 62 these criticisms indicate clear divisions within the United States government when it came to the Pacific War Memorial, despite its embodiment of Cold War rhetoric.

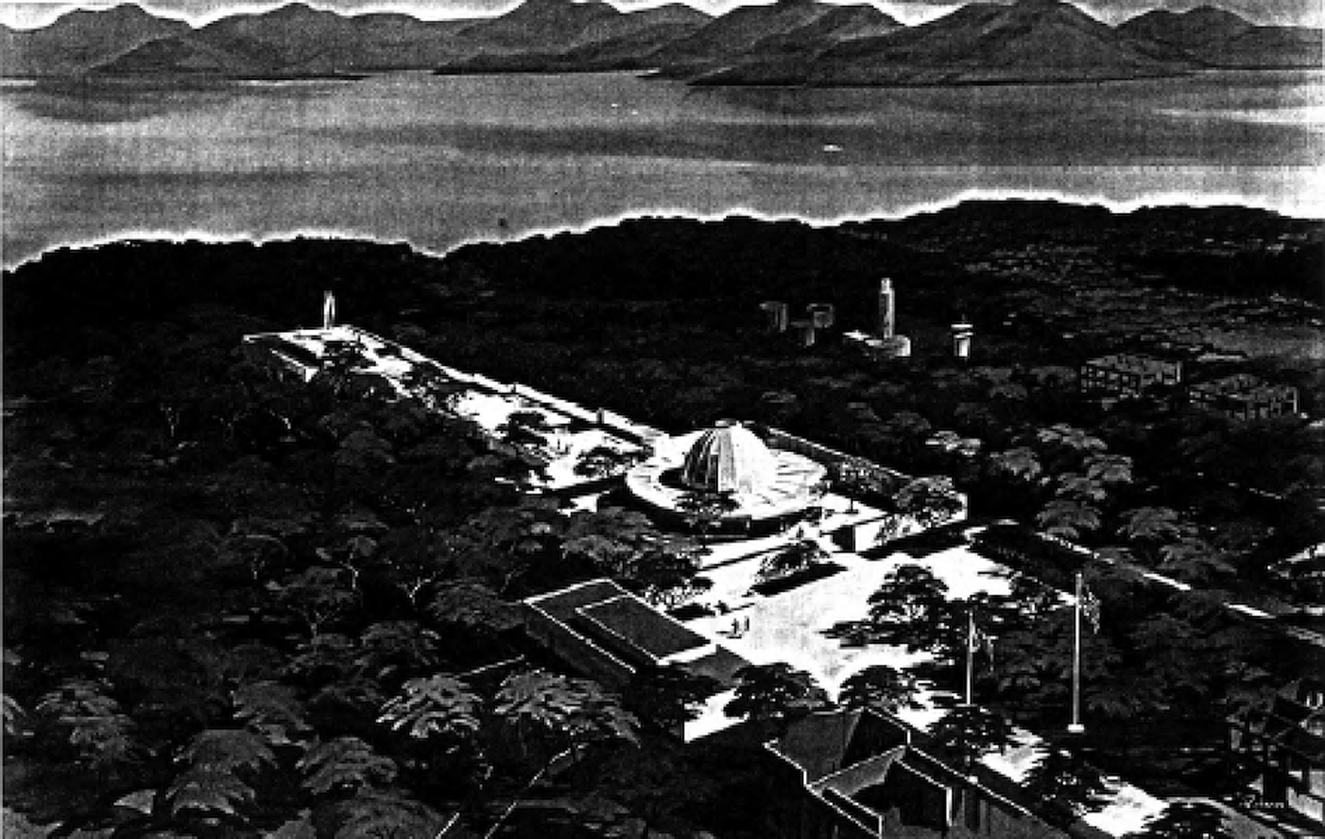

Edwards argues that a broader “transatlantic memory” emerged as a consequence of memorials being shaped by “commemorative agents” on both sides of the Atlantic.Footnote 63 In the Philippines, however, the genesis of the Pacific War Memorial was very much formed by the Corregidor Commission, and in particular the vision of its chairman, O'Neal. Although the Philippine Commission was involved, in reality it had little say over the memorial's final manifestation. Indeed, following a redesign of the memorial in 1965 after a final budget of $1.5 million was agreed (Figure 3), O'Neal wrote that the Philippine Commission could not be consulted due to their “inability” to schedule a trip to the United States by July 1965 when the judgements were being made.Footnote 64 The new proposal by Naramore, Bain, Brady, and Johanson depicted a domed “memorial room opening on a long vista ending in a symbolic monument depicting the flame of freedom.”Footnote 65

Figure 3. Redesign by Naramore, Bain, Brady, and Johanson, 1965. Courtesy of the Lyndon Baines Johnson Presidential Library. Image: White House Central Subject Files, Box 377, File 8, LBJ Library.

A “WAR MEMORIAL, FOR ALL MEN AND FOR ALL SEASONS”

The design of the Pacific War Memorial communicates much of the Corregidor Commission's and O'Neal's vision. Upon approaching the structure the visitor is confronted with a marble tablet that identifies the title of the memorial and contains the following inscription:

Erected To The Filipino And American Fighting Men Who Gave Their Lives To Win The Land Sea And Air Victories Which Restored Freedom And Peace To The Pacific Ocean Area.

This immediately establishes its purpose as a memorial to the Pacific conflict in its entirety, and also reinforces the significant role that the United States and the Philippines played in “restor[ing] freedom and peace.” Additionally it underlines the necessity of American and Philippine cooperation, without which, it is implied, this peace would not have been achieved. The marble inscription also emphasizes the consequence of this particular conflict; it is an event to be remembered, as O'Neal wished. This sense of permanence is continued as one advances through the memorial. The enclosed space created by the marble walls surrounding the “ceremonial court” is the first area encountered by the visitor, from which one proceeds through a small entry out onto the walkway either side of which are marble tablets listing each of the major battles of the Pacific conflict (Figure 4), including those fought by Philippine guerrilla forces after the surrender of American and Philippine troops in 1942.

Figure 4. Pacific War Memorial, Corregidor, Philippines. Photograph by the author.

Despite the elements of Western neoclassicism – the Travertine marble from Italy and the domed memorial room – there are Philippine elements in the design, such as the local foliage contained within concrete planters to “break the expanse of marble and stone.”Footnote 66 The concrete had a practical function, as the architects wanted materials to be unaffected by the elements,Footnote 67 again ensuring the memorial's longevity. The walls either side of the walkway were intended “to screen from view the base of the jungle growth and serve to direct the eye towards the monument at the end of the vista.”Footnote 68 Thus, although Philippine elements are embedded in the memorial, they are very much contained whilst naturally occurring foliage is excluded. The bordering pools along either side of the walkway similarly represent an artificial addition to the memorial. Nothing is included in this memorial that does not serve a specific function. In this case, the pools symbolize the “blood, sweat and tears they [the armed forces] spilled enrich[ing] the soil to make this world a better place to live in.”Footnote 69 O'Neal's message and the American legacy were paramount.

The walkway terminates in steps leading to a raised platform upon which sits a sculpture entitled the Eternal Flame of Freedom, designed by the sculptor Aristides Demetrios (Figure 5). This feeling of enclosure prior to reaching the open space around the Eternal Flame of Freedom ensures “emotionality,” a key component of memorials, according to White,Footnote 70 and it enables the visitor to physically experience the attainment of freedom. As noted earlier, eternal flames are often used in memorials to commemorate loss; however, here the Flame of Freedom is intended to be a “clearly understood living expression of the precepts of democracy and liberty.”Footnote 71 Its inclusion recalls the Corregidor Commission's original plans to erect a replica of the Statue of Liberty. Thus, as he intended, O'Neal literally ensures that the “torch of liberty” is passed from the United States to Asia. If the symbolism was not immediately apparent, the description beneath the sculpture reads, “To Live In Freedom's Light Is The Right Of Mankind.”

Figure 5. Eternal Flame of Freedom, Corregidor, Philippines. Photograph by the author.

The Christian elements of the memorial, primarily manifested in the altar at the centre of the “memorial room” (Figure 6), function to establish the significance of the space. There is also a sign erected by the Corregidor Foundation, which can be viewed just before entering the “ceremonial court,” that describes the Pacific War Memorial as a “sacred place” and lists various behaviours, such as eating and drinking, that are as a consequence prohibited. Together with the altar, the circumscription of behaviour makes it reminiscent of a place of worship. Upon the altar is an inscription:

This poem, written by American author N. E. Graham, not only serves to reinforce the attainment of freedom that came as a consequence of the American and Philippine lives lost, but also functions to imply that those who died fought for a righteous cause, one sanctioned by God. This is strengthened by the folklore that surrounds the memorial room dome and altar. On a personal visit to the site the guide informed us that the sun shines directly through the hole in the centre of the domed roof and onto the altar on 6 May, the anniversary of the surrender of Corregidor to the Imperial Japanese Army. This is also repeated in guidebooks and by visitor comments online,Footnote 72 although other visitors have reported that they have waited for such an event to no avail.Footnote 73 However, regardless of its accuracy, the existence of this folklore serves to reinforce the righteousness of the cause for which these soldiers died.

Figure 6. Pacific War Memorial, Corregidor, Philippines. Photograph by the author.

For O'Neal, the memorial's spiritual element was particularly significant. He felt it important that the Pacific War Memorial “inspire a feeling of reverence to the memory of those who died,”Footnote 74 and that it convey “the high purposes of the United States” to visitors.Footnote 75 The poem is embedded in the language of memorialization, which Inglis has observed on war memorials since the First World War in their function to “comfort and to uplift, not to instruct in the realities of war.”Footnote 76 The Second World War is to be understood as having achieved a particular purpose, one that is not simply sacred but Christian, creating an exclusive space for O'Neal's idealized community, as for him Christianity was “man's greatest defense against communism.”Footnote 77

Architecturally, the Corregidor Commission wanted the Pacific War Memorial to be an example of new design, symbolic of the new direction and relationship the United States should have with its former colony.Footnote 78 Thus, although the memorial recalls an American tradition of memorialization in the listing of battles fought, a feature present on most American memorials in Britain and France, architecturally it is otherwise very different. Memorials in France, for example, either are very classical in design, with Doric, Ionic or Corinthian columns, or they simply feature an obelisk. Additionally, they all incorporate American motifs such as the flag and the eagle. In contrast, other than the references to the American forces, there are no American motifs present in the Pacific War Memorial. Additionally, whilst its form is reminiscent of an earlier design by the consulting Philippine architect on the memorial, Leandro Locsin,Footnote 79 it does not feature any distinctly Filipino architectural elements or motifs.

Instead the architectural language is far more universal and includes elements that have been historically attributed to memorials worldwide. For example, the reflecting pools around the outside of the ceremonial court and alongside the walkway are found in memorials from the Lincoln Memorial to the Taj Mahal, and similarly the domed rotunda is also present in the Australian War Memorial, which was founded in 1941. These memorial elements familiarize the Pacific War Memorial, making it a recognizable memorial space. However, its American architectural design and English inscriptions, as well as the limitations on the Philippine natural elements and its promotion of democracy and freedom, ensure that it physically articulates O'Neal's wish to convey the success of the United States’ mission in the Philippines.

Construction of the Pacific War Memorial finally began on the anniversary of Corregidor's surrender on 6 May 1967 and it was inaugurated by President Marcos on 22 June 1968. Inglis has noted that the unveilings of memorials following the First World War usually have three components, “the national, the sacred and the military.”Footnote 80 The opening of the Pacific War Memorial was no different, with the presence of national figures, including President Marcos; the United States ambassador to the Philippines, G. Mennen Williams; Catholic Church leaders, and both American and Philippine military veterans. Williams used his speech to reiterate the agenda of the memorial as emblematic of American and Philippine “devotion to common ideals of freedom,”Footnote 81 whilst Fr. Pacifico A. Ortiz reinforced the sacredness of the conflict, referring to Corregidor as “hallowed ground” and the military as “those whom God has chosen.”Footnote 82 Similarly, the commemorative activities within the ceremony also fulfilled this memorial triad, with the raising of flags and the playing of national anthems, in addition to prayers and the laying of wreaths.Footnote 83

Inglis has also noted the masculine nature of these ceremonies, with women present but silent.Footnote 84 Indeed, although the wife of President Marcos, Imelda, was present, her sole function was to cut the ribbon to symbolically open the memorial. The Pacific War Memorial also reinforces its masculinity through its language and the absence of women, who served on Corregidor as nurses, from the tablets marking the dead. A booklet produced for the opening ceremony describes the memorial as a “war memorial, for all men and for all seasons,” additionally referring to the Philippine and American forces as that “select mold of men who knew how to die.”Footnote 85 Not only does this highlight the maleness of the memorial space and the conflict as a male achievement, but it also equates masculinity with civic duty. Indeed, President Marcos articulated this belief in his speech, The Struggle for Peace, at the opening. Although initially reiterating the familiar rhetoric, describing Corregidor as a “common shrine to the spirit of freedom and the valor of our two peoples,” he also looks forward, stating, “we have beaten the swords into plowshares, and the spears into pruninghooks; and we are determined that our sons shall not learn war anymore.”Footnote 86 Thus again civic or national duty is framed as a masculine effort. However, whilst this excludes women, it also challenges the agenda of the Pacific War Memorial by questioning the purpose of the war. Marcos's rhetoric suggests that Philippine prosperity has come as a consequence of his leadership, as opposed to American and Philippine cooperation. Thus while Marcos initially framed the memorial using the same American oratory that emphasized the importance of freedom and the Philippine–American alliance, he also used it as part of his own nation-building rhetoric.

THE CORREGIDOR MEMORYSCAPE

This parallel narrative of Philippine nationalism has also emerged on Corregidor itself following the inauguration of the Pacific War Memorial. At present, unless one can access a boat, the Pacific War Memorial can only be visited as part of the Sun Cruises Tour of Corregidor, which takes the form of a ferry ride from Manila Bay to the island, where several trolleybuses meet disembarking passengers to take them on a guided tour. Sites visited include the Pacific War Memorial, former military barracks and other sites associated with the Second World War, as well as newer monuments and memorials that have been built since the Corregidor Foundation took over the management of the island in 1987. These newer memorials include the Filipino War Memorial or Heroes Memorial.

It is at this memorial that commemorations take place on Bataan Day, or as it is now known, Araw ng Kagitingan, which is the national day to remember the Second World War dead. The director of the Corregidor Foundation explained that services took place at the Filipino Heroes Memorial as opposed to the Pacific War Memorial as the latter was “for the allies,”Footnote 87 suggesting that he does not see the Philippines as part of that group. Thus, although the anniversary of the Fall of Corregidor itself is remembered at the Pacific War Memorial, its absence when specifically remembering the Philippine dead suggests not only its lack of significance to many Filipinos, but more particularly its perceived irrelevance to the national narrative that the government wishes to project.

From the first remembrance services on National Heroes Day following the end of the Second World War, the Philippine government has worked to place the Second World War within a nationalized history. Indeed, the island's Malinta Tunnel Experience serves this function. Through a series of films and dioramas, the Malinta Tunnel illustrates the conditions on the island whilst it was under siege from the Imperial Japanese Army. Intertwined with this is the story of Philippine Commonwealth President Manuel Quezon, who took his oath of office on Corregidor when the government was forced to relocate to the island following the Japanese invasion in December 1941. The exhibition depicts Quezon's struggle for Philippine independence, from his own participation in the 1898–1902 Philippine–American War through to his political career, during which he secured the passage of the Tydings McDuffie Act, which provided for the Philippines to become an independent country after a ten-year transition period. The exhibition culminates on Philippine Independence Day on 4 July 1946. Thus the Malinta Tunnel Experience serves to localize the Second World War by framing it within the country's historical struggle for self-rule. Together with the Filipino Heroes Memorial, these memorials function much like the Pacific War Memorial in their message of freedom, except that here the freedom is not universal, but national, and the Second World War is not a global conflict but the final Philippine revolution in a centuries-old fight for independence.

In addition to these memorials the Corregidor Foundation has also allowed for Japanese narratives of remembrance to be present on the island. These take the form of memorials that have been erected by private Japanese citizens and veterans’ groups and are located in the Japanese Garden of Peace. One of the memorials is dedicated to “the memory of the war victims,” in which the dedication includes Philippine, American and Japanese soldiers. Another is dedicated to “the souls of the Filipino, American and Japanese, soldiers whose lives were given in a battle which occurred here on May 5, 1942.” Yet despite the presence of these Japanese remembrances, they are marginalized on the Sun Cruises tour. Japanese tour groups are separated from the other tourists, and throughout the author's tour the guide frequently made reference to the atrocities committed by the Japanese forces and drew the group's attention to the separation of the Japanese tourists, stating that it was because they would not want to hear about the brutalities that occurred. When the tour arrived at the Japanese Garden of Peace, the guide remarked on incidences of Second World War veterans refusing to enter the garden and one occasion of a memorial being defaced by an American veteran.

Outwardly the Garden of Peace expresses a symbol of renewed friendship between Japan and the Philippines, undoubtedly influenced in part by the Philippines’ increased economic reliance on Japan.Footnote 88 Incidentally this alliance is also promoted through the official commemorations during Araw ng Kagitingan with the presence of the Japanese ambassador alongside their American and Philippine counterparts. However, on Corregidor the touring groups are encouraged to remember the war as the guide suggests, and as it is presented throughout the island: as a scene of American and Philippine suffering at the hands of the Japanese and as a fight for freedom (from the Japanese). The separation of the Japanese tour groups suggests that while alternative remembrances are tolerated, they are not allowed to infringe upon the official narrative of war presented. Indeed, a few of this author's interviewees involved in Second World War official remembrance activities commented on the absence of an apology from the Japanese government for the “atrocities” committed, making it clear this is still a prevalent issue and the narrative of reconciliation is not one subscribed to by everyone.Footnote 89 Despite the presence of memorials and displays that function to embed the Second World War within a nation-building narrative, the Sun Cruises tour continues to reinforce O'Neal's wish to commemorate “the joint sacrifices of brothers-in-arms.”Footnote 90

However, this collective “sense of the past” has been contested by other “commemorative agents.”Footnote 91 The past few decades have seen the construction of a number of other memorials funded by private groups, such as the Memorials to the Military Women and the Memorial to Jonathan M. Wainwright, “Hero of Bataan.” These reveal the lives and voices of those who are forgotten or lost within the Pacific War Memorial itself. Furthermore, on speaking to both Philippine and American interviewees involved in Second World War commemoration, the absence of the personal and indeed the Philippine element of the Pacific War Memorial affects the way in which it is used. Additionally, when speaking to the son of an American veteran about the Pacific War Memorial, he noted the “official” ceremonies that took place there, but more significant to him were the death march markers that line the route of the Bataan death march, of which his father was a part.Footnote 92 Thus, whilst official “practices” of commemoration still take place at the Pacific War Memorial,Footnote 93 the absence of other practices of remembering – the Filipino commemorations taking place elsewhere, the personal remembrances of the son of an American veteran at the Bataan death march markers – suggest its irrelevance to both official Philippine commemorations and personal American and Filipino remembrances of war.

CONCLUSION

In the aftermath of the Second World War, a shared narrative of remembrance between the United States and the Philippines emerged around the memorialization of Bataan and Corregidor. The articulation of the conflict as a fight between liberty and oppression was informed by American Cold War rhetoric and in particular the Truman Doctrine, as articulated in a speech delivered by President Truman to Congress on 12 March 1947 in which he dichotomized freedom and communism.Footnote 94 Yet at the same time the Philippine memorial landscape was also being shaped by the Philippine government and Philippine veterans who placed the war firmly within a Philippine narrative through distinctly Philippine days of remembrance, such as National Heroes Day and Bataan Day, and Philippine memoryscapes, such as Capas and Bataan.

Likewise, American Cold War foreign policy shaped the Corregidor Commission's and O'Neal's visions for the Pacific War Memorial. Yet O'Neal also had his own desire to memorialize the United States’ imperial legacy. Whereas Edwards notes a collaborative enterprise in the formation of American memorials in Europe, in the case of the Pacific War Memorial, despite some involvement by the Philippine National Shrines Commission, its development was dominated by O'Neal and the Corregidor Commission.Footnote 95 Although Edwards views the “officers of government agencies” as a singular “commemorative agent,”Footnote 96 it is clear from O'Neal's agenda and his reluctance to involve the American Battle Monuments Commission that he saw their motivations for commemoration as very distinct. Instead the Pacific War Memorial can be understood as having been shaped by what I have termed “commemorative agendas,” indicating the equally emphatic motivations of both individuals and groups. Additionally, the “assertiveness” noted by Edwards as a key feature of the second phase of American transatlantic memorialization after 1970 can be seen much earlier in the Philippines, as the United States tried to secure its connection with a rapidly decolonizing continent.

This “territorialization of memory”Footnote 97 is manifest in the Pacific War Memorial. Although ostensibly a “battlefield monument,” the Pacific War Memorial stands as a marker of the liberty that O'Neal perceived the United States to have bequeathed to the Philippines. It is best articulated in a speech given by American ambassador to the Philippines Paul McNutt, on Philippine Independence Day in 1946: “Though their land is devastated, the people are determined to rebuild upon the ruins, to raise here upon the ashes of destruction, a shining new nation, worthy of the great heritage of freedom we have left here.”Footnote 98 Yet whilst the colonial narrative of shared suffering and an American–Philippine fight for freedom persists on Corregidor, the absence of the Pacific War Memorial from Araw ng Kagitingan remembrance events and the presence of memorials and exhibitions such as the Filipino Heroes Memorial and the Malinta Tunnel Experience disrupt O'Neal's vision. As the government seeks to embed the country's liberty within its own heroic past, freedom is less a consequence of the American presence than it is the inevitable outcome of the Philippines’ own historical struggle for self-rule.