Introduction

Twenty years after the passing of Resolution 1325, the participation of women in international peace and security as military personnel remains limited to specialised areas and mainstreaming has not occurred. On 13 October 2015, UNSC Resolution 2242 called on the Secretary-General ‘to initiate, in collaboration with Member States, a revised strategy, within existing resources, to double the numbers of women in military and police contingents of UN peacekeeping operations over the next five years’.Footnote 1 On 28 August 2020, the Council unanimously adopted resolution 2538 on women in peacekeeping operations.Footnote 2 Initiated by Indonesia, it contains a set of 12 guidelines on ways member states can promote the increased participation of women in peacekeeping. The specific focus of 2538 was on increasing the number of uniformed personnel in peace operations and the need for member states to ‘support greater participation of women in peacekeeping operations, including through sharing best practices for recruitment, retention, training, and deployment of uniformed women’.Footnote 3 We focus here on women's participation as military personnel and not in policing or administrative roles, which is beyond the scope of this article.

We argue that increasing women's participation in peace operations requires an increase in the number of women in national militaries and a change in mindset to improve recruitment and retention. While increasing numbers is important for mainstreaming, an increase in women's meaningful participation in military life requires a shift in how status is awarded to different roles in the military and a change in how women are deployed. Drawing on empirical data, this article highlights the problems inherent in mainstreaming Resolution 1325 across national militaries and peacekeeping operations. We show that women remain under-represented in their national militaries and particularly in high-status combat positions. We contend this affects their promotion chances and this, alongside societal inequalities, influences the retention and recruitment of women in the armed forces. In addition we draw attention to a second feature of women's service as armed personnel, the relegation to specialised spaces in peacekeeping operations. We capture these issues under the term ‘sidestreaming’ and we discuss how this occurs both in national militaries and peacekeeping operations.

Sidestreaming is a concept we define as the practice, deliberate or unintentional, of sidelining women and relegating them to specialised spaces in international peace and security while attempting gender mainstreaming or increased gender integration. The term captures how the process of mainstreaming can be subverted, fail to challenge hegemonic masculinity, and perpetuate a simplistic and traditional dichotomy of women and men's capabilities as protector and protected or as Sabrina Karim and Kyle Beardsley term it ‘warrior-peacemaker’.Footnote 4 In the context of national militaries and peacekeeping, sidestreaming highlights the tension between the overt recognition women obtain for the unique roles they play in military contexts where gender sensitivity is required; and simultaneously, how the low status of non-combat roles obscures women's visibility and the value of their contribution in national militaries. This negatively impacts female recruitment, retention, and promotion leading to low representation in national militaries, and hence contributing to the low numbers of female military personnel in peace operations.

Women currently comprise just under 5 per cent of uniformed military personnel in UN peacekeeping missions.Footnote 5 While the majority of peacekeeping troops currently come from the Global South,Footnote 6 we suggest, that with some notable exceptions such as India and Uruguay,Footnote 7 an explanation for the low numbers of female military personnel in peace operations reflects a lack of gender mainstreaming in national militaries globally which spills over into peacekeeping. Owing to a dearth of accessible data on the numbers of women in national militaries worldwide, in itself a significant research gap, this article shows how sidestreaming occurs in both national militaries and peacekeeping operations. Our research indicates that Global North militaries do not appear to differ greatly from those in the Global South in their commitment to mainstreaming in practice, despite a great deal of rhetorical commitment.Footnote 8

The contribution of this article is that it provides up-to-date empirical data on women in national militaries worldwide, illustrating how women remain under-represented and under-valued in many areas of military life. We argue that this impacts the numbers of women available to serve as military personnel in UN peacekeeping operations and show how the quality of women's service when peacekeeping is negatively affected by sidestreaming. We concur with Karim and Beardsley that increasing women's contribution to peace operations is important because peacekeeping operations are vehicles for the advancement of gender reforms in the postconflict environment.Footnote 9

This article is informed by a review of the available literature and data on women's participation and inclusion in national militaries and peacekeeping. Our search terms included: gender, women, female, recruitment, retention, participation, promotion, roles, hierarchy, women in the military, feminisation of the military, femmes dans l'armée, military servicewomen, women in combat, combat exclusion, and inclusion in relation to the military and peacekeeping spheres. Data sources included: academic peer reviewed journal articles and books; government statistics and white papers; national ministerial and military reports; think tank papers and newspaper articles going back as far as 1980. The languages used in our sources were English, French, and Spanish. For the numeric data on female participation in national militaries, only data from the past five years (2015–20) was used. To ensure our data has relevance to the current spread of troop contributing countries in peacekeeping, we prioritised data searches on the top twenty Troop Contributing Countries (TCC) in UN peacekeeping. However, owing to severe shortages in available data,Footnote 10 both qualitative and quantitative, we draw on NATO figures to obtain a fuller picture of the current status of women in national militaries globally. Of note is that we find the Global North and South do not vary a great deal in terms of women's participation and inclusion. We believe this review provides a useful contribution in that it highlights: (1) the lack of readily available data on women serving in national militaries and their experiences; (2) provides a useful update on the state of the literature on this topic; and (3) draws attention to the problems women encounter when building a military career.

The article proceeds as follows. Section one provides a discussion of the meaning of participation and gender mainstreaming in international peace and security as outlined in key documents: UN Resolution 1325 and the Windhoek Declaration. The next section then provides a brief review of feminist thought on women and combat and a discussion of the hegemonic masculinity inherent in national militaries. The third section provides a review of women's participation in national militaries. It finds that militaries remain a largely masculine environment with female participation hovering at around 11 per cent worldwide.Footnote 11 In addition women are clustered in lower status occupations that do not involve direct combat, which limits their opportunities for promotion and inhibits retention. We also show how, despite some recognition from national militaries of the need to recruit women, militaries continue to avoid making an explicit connection between women and combat, either excluding them from images of war, or placing them in images that show them in specific roles that perpetuate a ‘beautiful souls, noble warrior’ orthodoxy.Footnote 12 This section concludes that full participation is key to women's retention and promotion, and that greater visibility of women's presence in the military is essential for recruitment. The next section shows how in the field, female military personnel in peacekeeping operations are often directed into specialised spaces restricting their full professional development. It is here that the tension between the ‘special’ role of women, and gender equality for female military personnel is very evident. Despite 1325 being a UN initiative, in the military aspect, peace operations are not being used as an opportunity to expand and grow women's experience in combat or mainstream women in line with the resolution. We find that women's visibility is only part of the problem and that a more gender-equitable military structure is required to avoid sidestreaming. In the conclusion we contend that a shift towards human security, cosmopolitan, post-national defence,Footnote 13 and awarding higher status to non-combat roles will foster increased female participation in militaries and challenge the masculine narratives that predominate in the military. The final section proposes an agenda for future research and provides some policy recommendations.

Resolution 1325 and The Windhoek Declaration

The four pillars of Resolution 1325 comprise participation; prevention; protection; and relief and recovery.Footnote 14 In this article we refer to the concept of participation that is mentioned in the resolution in relation to peace processes; the promotion of international peace and security; and at the decision-making level both in conflict and peace processes.Footnote 15 Specifically the resolution calls for the ‘equal participation and full involvement in all efforts for the maintenance and promotion of peace and security’.Footnote 16

In addition to participation, UNSCR 1325 calls for gender mainstreaming across all peacekeeping operations.Footnote 17 The Windhoek Declaration also emphasised the need to include women at all levels of UN peacekeeping. Specifically:

In order to ensure the effectiveness of peace support operations, the principles of gender equity and equality must permeate the entire mission, at all levels, thus ensuring the participation of women and men as equal partners and beneficiaries in all aspects of the peace process ….Footnote 18

The declaration provided a comprehensive outline of the steps required to mainstream gender in UN peacekeeping. Of particular relevance here is the section that refers to the recruitment of more women into peacekeeping operations which calls for: (1) the need to increase the number of women in military and police forces who are qualified to serve in peace operations at all levels including the most senior; (2) the need to encourage other potential troop contributing nations to develop longer term strategies that increase the number and rank of female personnel in their respective forces; and (3) that the eligibility requirements for all heads of mission and personnel should be reviewed and modified to facilitate the increased participation of women.Footnote 19

From the above, two main points relevant to this article can be derived: in defining mainstreaming, the Windhoek Declaration explicitly states that if more women are to be included in international peace and security, we need to increase the numbers of women in national militaries and police forces available to serve in peace operations and that this should occur concurrently with mainstreaming in UN operations. The second key point is that mainstreaming involves infusing gender equality throughout an entire mission,Footnote 20 and this by default means ensuring women must have meaningful access to all areas of military life. In this article we discuss both national militaries and the military aspect of peacekeeping in the same space because we agree with the declaration that these issues are connected. In other words, if you have low numbers of women in your infantry, you won't have many to send to UN peace operations, in particular at senior levels.Footnote 21 Furthermore, we concur with Annica Kronsell and Erika Svedberg's contention that the making of war ‘is increasingly associated with peace’ and therefore view the inclusion of peacekeeping in a discussion of women's experiences of the military relevant as we assess how sidestreaming occurs.Footnote 22

Feminist theorising on gender and the military

Until now, the literature on the WPS agenda has acknowledged that gender mainstreaming has not occurred across all pillars of 1325.Footnote 23 Laura Sjoberg and Carol Gentry (2015), for example, term mainstreaming in militaries ‘malestreaming’ for this reason.Footnote 24 Within the feminist literature there are broadly two positions on women's participation in the military: those that oppose militarism in all its forms and those that choose to engage with it.Footnote 25 However, Cynthia Cockburn (2012) draws our attention to the nuance in these positions and the limitations of categories such as ‘radical’, ‘socialist’, and ‘liberal’ feminism, reminding us that these varied positions are not mutually exclusive. Drawing on the work of Chela Sandoval and her concept of a ‘differential mode of oppositional consciousness’, she posits different feminist theories should be applied intelligently and tactically depending on the problem under examination.Footnote 26 Broadly speaking however, anti-militarist feminists take an emancipatory approach that aims to alter the very nature of national institutions. They take aim at the gendered assumptions of militarism that perpetuate war by making the coercive use of violence seem like a reasonable solution.Footnote 27 The critique is that attempting to gender mainstream in security institutions means working within a system based on masculine gendered norms. For some feminists then, the study of war and women's role in combat only serves to legitimise the hegemonic masculinity in of the existing patriarchal system. Research in this vein raises the point that while women may not be formal actors in war, they suffer disproportionately as a result of war and its spillover effects and this should be prioritised as a research topic.Footnote 28 Cynthia Enloe contends that the word combat is a loaded term that marginalises almost all incidences of violence that women face on a daily basis except that of armed conflict.Footnote 29

Anti-militarist approaches contend that militaries are patriarchal institutions that perpetuate violence and as such greater inclusion of women in militaries should not be considered feminist progress. Sybil Oldfield sums up this view stating, ‘Women are not essentially anti-military, but militarism is essentially anti-feminist’.Footnote 30 Enloe argues that winning the right to fight represents a militarisation of the women's liberation movement.Footnote 31 Sandra Whitworth argues even peace operations should be considered to be advancing an imperialist agenda that reinforces ideas about the Global South being conflict-prone, uncivilised, and diverting our attention from the roots of conflict that she posits are colonialism and globalisation.Footnote 32 V. Spike Peterson and Anne Sisson Runyan note that all five members of the United Nations Security Council are also the largest arms dealers in the world.Footnote 33 The assumption is that adding more women will not alter the patriarchal nature of the military and that a more revolutionary and emancipatory approach is required.Footnote 34

Conversely, some feminists, and in particular liberal feminist approaches argue that greater inclusion of women in national militaries, and treating women as equals in the national military will contribute to greater gender equality overall. Caroline Kennedy-Pipe notes: ‘For liberal feminists, the great institutions such as national legislatures, judiciaries and armed forces had to be open to women. The struggle of women to serve at every level in national militaries, including, for many, the “right to fight”, became a preoccupation for some liberal feminists in the Western world.’Footnote 35 This approach, in line with other types of feminism, rejects notions that women are more peaceable and inherently less violent than men.Footnote 36 Furthermore, they argue that military service has traditionally been a sign of full citizenship and therefore exclusion signals women's lower civic status.Footnote 37

Liberal feminist approaches currently dominate practitioner debates. They may take or engage with essentialist approaches to gender,Footnote 38 and focus on how women are deployed once the barriers to inclusion in all military activities have been removed. Although until now, the Global North does not appear to be more advanced in gender mainstreaming than the Global South,Footnote 39 and women's experiences of the military in the Global South remain under-represented in feminist literature.Footnote 40 We cannot therefore state with certainty the relevance of the ‘the right to fight’ to women in the Global South. Research on disarmament, demobilisation, and reintegration (DDR) programmes has shown that more often than not, women in many states are already fighting on the front lines and therefore it is recognition, reward, and social acceptance they seek, not the right to do so.Footnote 41 Furthermore, as Brenda L. Moore notes, even in the Global North, allowing women to fight on the front lines may be popular among white female officers, but may not suit enlisted women of colour owing to the limited choices they face both within the military and society more broadly as a result of structural inequality.Footnote 42

Across all feminist perspectives, the military is recognised as being an institution dominated by a culture of hegemonic masculinity (or hypermasculinity) that remains highly resistant to change and perpetuates the norm of heterosexual masculinity in connection with the use of violence.Footnote 43 Hegemonic masculinity refers to a set of masculine norms and practices that have become dominant and are supported by institutional power that makes them hegemonic and appear as if they are the natural order of things.Footnote 44 Military institutions reinforce and encourage the normalisation of gender subjectivities that assign particular roles to women and men in war and peace. In practice this manifests as ‘doing gender’, with behaviours, images, and texts all reinforcing an essentialist and simplistic dichotomy of men and women as protectors and protected.Footnote 45 For example, Aaron Belkin notes how feminising the enemy prior to inflicting violence is a regular part of military training and argues it is therefore unrealistic to expect male soldiers to treat women equally in other contexts. He adds that patriarchal entrenchment ‘reflects the gendered ways in which the armed forces socialize warriors’ and states that as long as no changes are made to basic training procedures, hegemonic masculinity will remain the norm in militaries.Footnote 46

In the peace operations literature specifically, Louise Olson and Theordora-Ismene Gizelis highlight the emergence of a schism between empirical and feminist research: ‘Feminist research has raised questions about the understanding and conceptualisation of peace and security, while empirical research systematically explores the gender dimensions of peacekeeping.’Footnote 47 However, recent feminist scholarship in international relations does bridge this gap, adopting a critical approach to the gendered aspects of military organizations while addressing the issue of gender mainstreaming.Footnote 48

We argue that increasing our empirical understanding of women's roles in security institutions is a valuable endeavour not least because it remains under-researched. As such, we concur with feminists who defend the study of war and who point out that pessimism about the immutability of patriarchy in the military may be uncalled for. Just as radical change may be unlikely, so it is unrealistic to assume that no change can take place given the changes regarding LGBT inclusion that has already taken place in the military.Footnote 49 Kronsell and Svedberg note the need for feminists to study the use of violence to ensure women have the opportunity to contribute to national security debates and ask questions about when the use violence might be necessary to avoid perpetrating the protector-protected dichotomy.Footnote 50 As Enloe notes, in the US at least, more and more feminists have concluded that the military ‘was too potent an institution in American life to be permitted to perpetuate its own masculinized fantasies’.Footnote 51 Issues such as: women's agency in combat and experiences of war; women's experiences as peacekeepers; and women's experiences of military institutions remain important foci of research because they can tell us something about how women might shape security institutions in a future situation of greater gender parity and equality.Footnote 52

Given the above, this article offers an assessment of the current situation of female military personnel. The following sections and remainder of the article draw on empirical research to show how sidestreaming occurs in national militaries and peacekeeping operations. We note again here the lack of available data on this topic that is problematic.

Women's participation in national militaries

Historically, the military has been a traditionally masculine domain that continues to be dominated by masculine culture. ‘By joining the military’, Emmanuelle Prévot argues, young boys were separated from the ‘maternal home, and more largely, from the world of women’.Footnote 53 This argument is echoed by Liora Sion, who contends that the military in many societies continues to be, ‘the bastion of male identity’, with military service being a ‘rite of passage into manhood’, and combat being the ultimate challenge to test military virility.Footnote 54 As such, the construction of military identities has been intricately linked to masculinity and its ideals, creating a normative conception of the ideal soldier who was a man with the characteristics of physical strength, courage, authority, and self-control.Footnote 55 The values and norms of military occupations were imbued with this masculine ideal presenting military service as ‘virile jobs destined for physically powerful men’, a notion still present today in representations of the military.Footnote 56 It follows that integrating women into the military contradicts the military's idea of itself; hence, women are not only seen as accessing a traditionally all-male terrain, but also ‘taking men's place’ within it.Footnote 57

Despite this, armed forces in many states worldwide now emphasise the need for the full and equal integration of women into the military,Footnote 58 highlighting the benefits and ‘added value’ of having more women integrate this institution.Footnote 59 When it comes to mainstreaming, the Global North does not appear to be ahead of the Global South: the US didn't allow women in combat roles until 2013,Footnote 60 and the UK only allowed women to fight on the front lines in 2016.Footnote 61 Even in the Israeli Defense Force (IDF), where 92 per cent of the jobs are open to women, combat roles in elite units remain closed to women.Footnote 62 However, while female participation in some national militaries may now be comprehensive on paper, in practice there remain significant issues. As Megan H. Mackenzie notes, it is not enough to simply add more women and expect that measure will ensure the meaningful participation of women:

While it would seem that removing any gender-based barrier is a positive step, the intense focus on combat exclusion also has the potential to limit debates if they ignore differences among women and place unreasonable expectations that a singular policy reversal could produce such profound results for all women within an institution infamous for resisting change.Footnote 63

Lifting combat exclusion doesn't mean that these roles become accessible to women. Women can also be excluded from high-status roles in other ways, ‘on the grounds of physical requirements, combat effectiveness, or [because of] the health problems associated with submarine service’.Footnote 64

There are several recurrent arguments against women's presence in the armed forces, which Sabine T. Koeszegi et al. describe as ‘widely held “cultural” norms and persistent beliefs’.Footnote 65 The most prevalent is that women are physically and psychologically weaker, and thus integrating them in combat roles, special ops, or even combat training would decrease the overall quality and effectiveness of combat units.Footnote 66 The presence of women in units is believed to erode the homosociality of units said to be central to their unity and hence operational success.Footnote 67 Masculinity is also used to encourage solidarity among soldiers and on the battlefield,Footnote 68 and feminine physicality, like menstruation and pregnancy is viewed as a weakness that will inhibit combat efficiency.Footnote 69

In some cases, structural barriers exist that limit the possibilities of potential women recruits. This has been reported to be the case in Indonesia, where the Indonesian Army Academy (Akmil) stopped recruiting female cadets in 2018, with women being able to enrol to the army only through ‘non-commissioned officer candidate schools’, negatively affecting their subsequent posting;Footnote 70 and in China, where the People's Liberation Army (PLA) has been accused of requiring higher and differentiated standards from women applicants.Footnote 71 Other deterrents exist that can impact a woman's decision to join the armed forces. These include, among others: negative and discriminatory societal attitudes on women as soldiers;Footnote 72 perceived issues around career flexibility;Footnote 73 and concerns around sexual harassment.Footnote 74

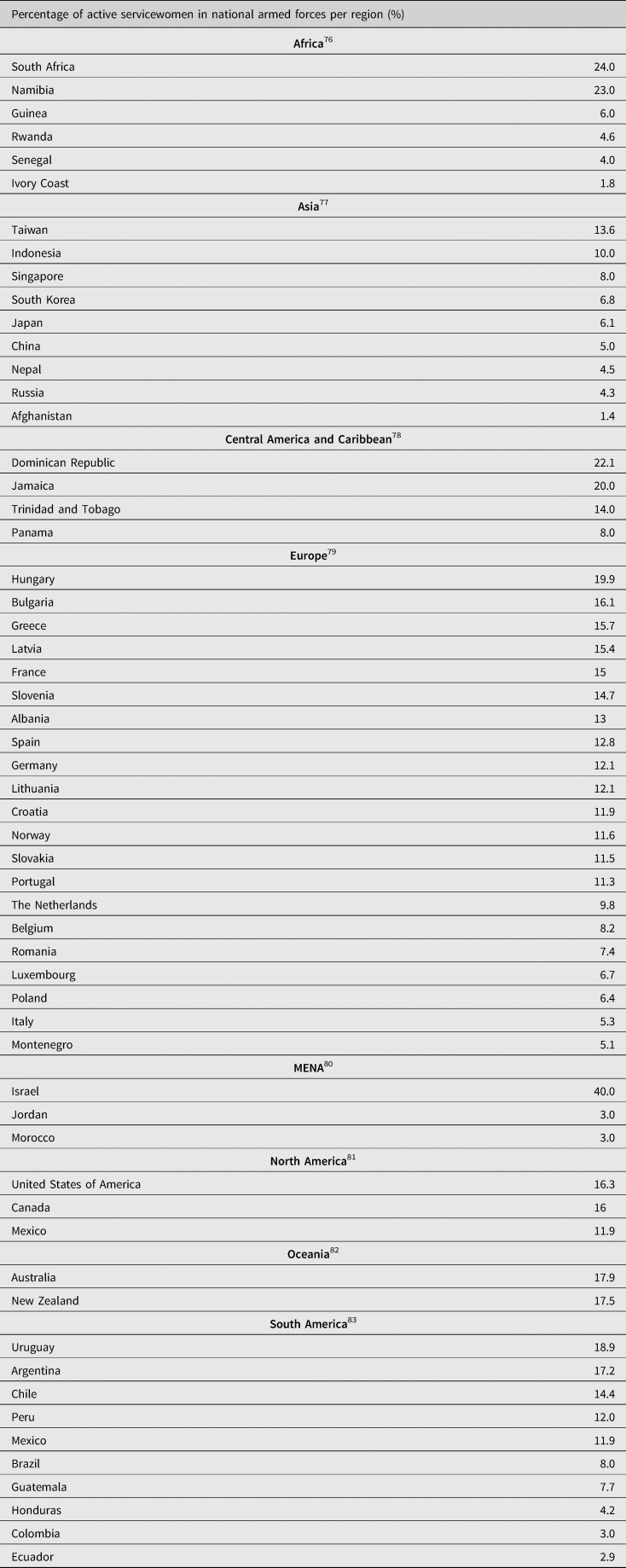

Despite these concerns, a percentage of women across the world do participate in their national armed forces and as noted above, national militaries are encouraging them to do so. Based on the available data, Table 1 shows the percentage of active servicewomen within militaries worldwide.

Table 1. Percentage of active servicewomen in national armed forces.Footnote 75

While these figures indicate women's participation in national militaries is low, to understand how women participate and experience the military, it is important to interrogate the roles they occupy. Again we find there is little difference between the Global North and South.

According to NATO reports, 33.1 per cent of servicewomen in member states’ armies were employed in non-combat services and supply corps, as technicians, military assistants, planning and management professionals, load masters, and different specialists. Hungary's large female workforce is clustered in the country's Ministry of Defence and subordinate offices (58 per cent).Footnote 84 AlgerianFootnote 85 and AustralianFootnote 86 servicewomen are concentrated in health roles. Within the Chinese People's Liberation Army, women have ‘traditionally served primarily in medical, communications, logistics support, academic, and propaganda roles’.Footnote 87

Overall, the norm throughout militaries continues to place servicewomen ‘mostly in subordinate or support positions where they remain aides to their male counterparts’.Footnote 88 While policies and legislation may theoretically put women at an equal footing as men, in practice, the full and comprehensive integration of women remains limited.Footnote 89 In fact, in most countries, women are excluded from combat roles and certain specialities that are deemed to carry a high risk of ‘exposure to fire or capture by an enemy’,Footnote 90 as combat is believed to be a male responsibility, with women needing protection.Footnote 91

The changing nature of warfare through the increased use of robotic and autonomous systems provides an interesting development as this technology is expected to reduce the physical requirements for ground combat, placing the onus on soldiers’ technical capabilities instead.Footnote 92 This undermines current arguments against women's physical capabilities and could lead to their greater integration in combat roles.Footnote 93 As one author notes, warfare in the automation era could create roles ‘where women may possess certain inherent advantages’Footnote 94 and could therefore contribute in a more equal manner. However this view could be said to still reflect ingrained gender roles and essentialist thinking that women are too weak for physical frontline combat. When women do enter these spaces however, the challenge will be to ensure that the space itself is not devalued or sidelined.Footnote 95

Instances of the gendered divisions of labour serve to illustrate the sometimes subtle but persistent sidestreaming of women in the military. Prevailing societal norms and attitudes toward gender roles relegate women to jobs that supposedly suit their gender and their ‘physical and psychological inferiority’.Footnote 96 In Montenegro and Serbia, doctors are said to routinely advise women against joining certain positions due to health concerns, despite no legal restrictions; in addition women perform self-censorship and simply do not apply.Footnote 97 Being barred from certain roles is one of the most significant factors hindering full female integration into armed forces. This corresponds to Emmanuelle Prévot's concept of vertical segregation and Helena Carreiras's idea of structural labour divisions,Footnote 98 which occurs when women struggle to progress to the highest ranks of the militaryFootnote 99 and are concentrated in the ‘lower-grade positions’.Footnote 100 Vertical segregation excludes women from leadership roles and from taking part in ‘the decision-making process’,Footnote 101 limiting their ability to make impactful changes that could benefit other women within the institution, for example, as senior mentors and role models that could help stem retention attrition.Footnote 102 In their study of the US air force, Kirsten M. Keller et al. found the majority of women surveyed wanted to be mentored by successful women in order to feel embedded in the organisation as opposed to on the fringes.Footnote 103

In 2014 the Report on Gender Equality by the European Parliamentary Assembly found that there are few women in the higher ranks of national militaries, and that women who hold senior ranks are mostly in administrative roles.Footnote 104 Career progression in the military is highly inflexible, often requiring officers to obtain career targets following a strict timeline, and any absences, such as maternity leave, carry ‘career penalties’.Footnote 105 Moreover, promotions to higher ranks is often tied to having combat experience. By being barred from such roles, and being sidestreamed into administration and support, women are by and large not accessing the positions that later enable them to reach the most senior ranks.Footnote 106

The New Zealand Defence Force (NZDF) reports that they have had no women above the level of Brigadier. Women have thus not been able to reach the top ranks in the NZDF, and instead ‘cluster in the lower and mid-ranks’.Footnote 107 In each of the French military corps, the percentage of women decreases as the ranks increase, with servicewomen tending to occupy the lowest positions in the hierarchy.Footnote 108 In the Uruguayan and Rwandese armed forces, women have only been able to climb to the roles of Major/Lieutenant Commander.Footnote 109 Likewise, a noticeable gender gap in rank distribution exists in the Nepalese Army, where despite a large increase in the total number of women in the army in the last ten years, the highest rank where women serve has not changed since 2011.Footnote 110

It has been suggested that as combat exclusion is increasingly lifted throughout militaries, more women will be able to experience career progression via this route, and obtain greater upward mobility in upcoming years.Footnote 111 This presupposes women will stay in service for many years, as currently, reaching the highest echelons of the military requires around 33 years of service.Footnote 112 However, persistent differences in retention between men and women remain.Footnote 113 Overall, women tend to stay in service less time than men, thereby impacting the feminisation of the military as a whole, particularly in senior ranks.Footnote 114

Erika L. King et al. find that servicewomen in the US are more likely to view military careers as short term due to their incompatibility with family life.Footnote 115 This perceived difficulty in balancing military life with family emerges as a critical issue impacting women's retention, and recruitment, throughout the literature.Footnote 116 The Rwanda Defence Force Gender Desk found that the work the army does is not always attractive to women, in part because ‘it adds to the triple roles of women [reproductive, productive, and community management]’.Footnote 117 Indeed, in many societies, women are still seen as mothers above all else, and are expected to perform mostly domestic roles, which are seen as being incompatible with a rigid military career and frequent deployments.Footnote 118 Interviewed Algerian servicewomen stated that at a certain point, they would have to ‘make a choice between family life and the military’,Footnote 119 despite legal protections and flexibility in place. The Keller study with female officers in the US air force found that ‘all focus groups discussed children or wanting to have a family as a key retention factor’, and noted that the frequent deployments and demanding schedules of a military career are a significant difficulty in achieving this.Footnote 120 All these findings point to the structural inequalities in society that still disproportionately award childcare responsibilities to women requiring them to navigate multiple roles in addition to their careers.Footnote 121 Interestingly, Mady Wechsler Segal et al. found that the challenges of balancing family roles and military careers can be mitigated by having a ‘female mentor who can relate’ to some of these specific issues, once again emphasising the importance of having women in senior mentoring positions.Footnote 122 Women cadets at West Point were found to be more likely to continue their military training when other women were present in their units, suggesting that the presence of women, not only in senior positions, also encourages retention. Footnote 123

Another contributory factor to the low numbers of women in national militaries is recruitment strategies. Advertisements for the military often reaffirm the link between masculinity and war by associating men with ‘markers of combat’.Footnote 124 However, women are often not portrayed with these same markers, thereby preventing ‘any association between women and warfare’.Footnote 125 Algerian service women, for instance, are ‘continuously represented in noncombat positions and excluded from the field’ in official advertisements.Footnote 126 In her analysis of US Army advertisements, Holly Speck found that women were not depicted in a wide variety of roles, but rather mostly depicted in ‘traditional gender roles such as civilian spouses’ and in the medical field.Footnote 127 On the contrary, men were much more likely to be portrayed in combat roles, and the male voice was featured much more prominently in advertisements.Footnote 128

The PLA's media strategy for example, focuses on the beauty of army women, posting videos that ‘highlight their skills in dancing, taking phone calls and wearing make-up’ and captions that point to how good-looking they are.Footnote 129 Hence we see militaries continuing to perpetuate the ‘beautiful souls, noble warrior’ syndrome identified by Ehlstain and others.Footnote 130 Recruitment processes that do not reflect the different roles open to women, or those that do not represent women in leadership roles, fail to convey the image of the military as an attractive career option, and are therefore less appealing to potential female recruits.Footnote 131 While choosing whether to enlist or not is based on a host of factors, active service members have noted that being able to talk and answer questions about female-specific issues with female recruiters had been particularly welcomed during their recruitment process.Footnote 132 Douglas Yeung et al. suggest that female recruiters may be key to attracting more women, as they instil more ‘confidence in young female applicants’, act as role models, and can better respond to their needs.Footnote 133 Targeted policies seem to be effective, as NATO found that when nations have specific policies in place for the recruitment of women, they ‘experienced a significant increase in the female applications’.Footnote 134

This research found current recruitment efforts to increase women's participation in national militaries are producing uneven results.Footnote 135 Militaries need to actively consider the kind of advertisements they release, as their choice of advertisements disseminates a message about gender roles and women's place in the military.Footnote 136 Yet, military promotional material has been found to maintain gendered divisions by reproducing stereotypical gender roles and placing women in marginal positions.Footnote 137

This section has argued that women are being sidestreamed in national militaries in both the Global North and South. While our research cannot conclusively demonstrate causality, it does shine a light on practices that appear (from the numbers at least) to have a negative effect on the retention, recruitment, and promotion of women in national armed forces. Basic arguments for the non-participation of women in national militaries remain salient conveyed through formal and informal gendered practices that include the non-visibility of women in combat roles (both practically and in media images), limited promotion of women owing to the high status afforded to direct combat roles that leads to a lack of mentoring, and weak retention due to a combination of societal and military pressures.

In this article we argue that women's participation in peacekeeping is connected to the low numbers we see in national militaries and for as long as UN peacekeeping is the sum of its militaries, this will remain the case. The following section unpacks how sidestreaming occurs in the field in peacekeeping operations, even under the auspices of UN missions that are designed to promote 1325. Here we find women are pushed into specialised spaces on the basis of their ‘unique’ qualities.

Women in peace operations

Between 1989 and 1993, just 1.7 per cent of military peacekeepers deployed by the UN were female.Footnote 138 In 2001, the share of women in military posts serving in UN missions had increased only to little more than 4 per cent.Footnote 139 Currently the number of female troops serving in peace operations abroad as uniformed military personnel is 3,950, which constitutes 4.8 per cent of all peacekeeping troops.Footnote 140

Despite these low numbers, women's participation in peace operations is deemed useful by the UN. In the local security environment women's presence enables security precautions to be applied to both the female and male populations.Footnote 141 In intelligence gathering initiatives, female peacekeepers’ access to both women's networks and male populations provides a holistic view.Footnote 142 In peacebuilding tasks, women are essential for accessing the non-elite sectors of the population who may have very different requirements for an equitable peace, which helps to develop a more representative solution.Footnote 143 Women have also been noted for their roles in winning ‘hearts and minds’ in counterinsurgency operations.Footnote 144 Women have been found to be better at diffusing tension at checkpoints,Footnote 145 in part because they are seen as less confrontational and more peaceful and cooperative.Footnote 146 Research has shown women are more approachable for victims of conflict related sexual violence (CRSV) and sexual abuse and exploitation (SEA) among the local population;Footnote 147 and accordingly provide a force with increased legitimacy.Footnote 148 Women can assist with female populations in security sector reform (SSR) and demobilisation disarmament and re-integration programmes (DDR);Footnote 149 and it has been suggested that their presence may motivate their male colleagues to behave better when out on patrol,Footnote 150 although this idea has been rightly disputed and critiqued not least for placing the responsibility for poor troop behaviour onto women. Footnote 151

However, these many successes do not indicate gender mainstreaming and in fact may perpetuate an essentialist construction of femininity.Footnote 152 Maya Eichler makes the important point that there remains a tension between equality and difference. On the one hand, women may be hailed as equal when they perform as soldiers, albeit in comparison with a set of masculine norms, but in other scenarios their differences are instrumentalised and retained for use in specialised spaces.Footnote 153 Susan Willett describes this situation as being both ‘idealised and undervalued’ at the same time.Footnote 154 In her study of Swedish peacekeepers Kronsell argues that this perception of women as a useful resource does not challenge the gendered nature of military institutions themselves. Rather it merely helps retain simplistic essentialist and dichotomous perceptions of men and women's capabilities. Of note is that research on this topic with female peacekeepers found that they viewed their peacekeeping contribution in the same specialised way as the national military they belonged to, suggesting they have been successfully socialised into their national military cultures.Footnote 155

Exclusion and sidestreaming in peace operations

Karim and Beardsley identify three main challenges faced by female military personnel in peacekeeping: ‘the exclusion of and discrimination against female peacekeepers; the relegation of female peacekeepers to safe spaces; and the Sexual Exploitation, Abuse, Harassment, and Violence (SEAHV) of female peacekeepers’.Footnote 156

The exclusion of women in peacekeeping can come from varied sources: not sending women to peace operations in the first place; keeping them in the base at all times when they're there; and restricting their movements when out on patrol. In order to meet demand for a fast deployment, national militaries often send Special Forces combat units to peacekeeping operations as they are equipped to deploy at short notice and these Special Forces rarely contain women.Footnote 157 Furthermore, militaries often recruit peacekeeping troops from their infantry battalions,Footnote 158 which means that troop contributing countries simply do not have enough women in these areas to supply a gender balanced force, the argument that we make here.Footnote 159 Encouragingly, however, armed forces with a higher proportion of women do tend to send more women to peacekeeping missions.Footnote 160

Some national militaries have demonstrated a reluctance to send women to challenging environments,Footnote 161 or Muslim majority states.Footnote 162 Previous research found that female soldiers are less likely to be deployed to missions located in countries with low levels of development and/or that have experienced higher levels of violence, especially sexual- and gender-based violence (SGBV).Footnote 163 Currently however, the largest numbers of female military deployments are in UN missions that experience high levels of violence so this may no longer be the case, although as discussed here, sidestreaming may well be occurring on the ground in these missions.Footnote 164

Once deployed, women experience other forms of exclusion in the form of restrictions on their movement. Kari Karame found in 1992, the new Force Commander at the UNIFIL mission explicitly forbade women to undertake frontline military roles, which meant the Norwegian battalion was forced to withdraw women from these functions. Despite protest from female soldiers across the mission, the policy remained in place for the duration of the Force Commander's tenure. Furthermore, the Norwegian military did not attempt to take the issue up to more senior levels, either in the Norwegian parliament or with DPKO in New York.Footnote 165 More recently, research by Karim and Beardsley found evidence that many women in the UNMIL mission were refused permission to leave the base. These orders came from their national battalions, were applied to military personnel and were much stricter for women than for men.Footnote 166

Sidestreaming occurs also with the practice of keeping female soldiers in ‘safe spaces’. This relegation of women to safe spaces can occur while out on patrol, preventing them from taking on specific roles because of male colleagues’ perceptions that they are in need of protection.Footnote 167 Bergman Rosamond and Kronsell, in their research on female peacekeepers in Afghanistan, found male troops tried to prevent women soldiers from speaking to men in the villages they patrolled.Footnote 168 Heidi Hudson found that women are often directed into civilian-like tasks and that their involvement in military peacekeeping remains almost insignificant.Footnote 169 The need to have women on patrol in Afghanistan has meant women are often assigned to female engagement teams or similar tasks which relates to the fact they're women and not professionally trained soldiers.Footnote 170 This may be hard to avoid in environments where more traditional values about cultural norms persist.

Sexual exploitation and abuse is a further problem for female peacekeepers, and the extent of it within UN missions is presently unclear. Sexual violence within militaries has been attributed to what several authors term a ‘warrior syndrome’ that promotes hyper masculinity; but it is hard to know the actual number of victims.Footnote 171 In the UNMIL mission, 17 per cent of women (at all levels of seniority) listed sexual harassment by their male colleagues as one of their five greatest impediments to completing their duties.Footnote 172 The UN now acknowledges this problem, with point 7 of UNSCR 2538 expressing concern and call for strengthened efforts for the UN and member states to ‘prevent and address and address sexual harassment within peacekeeping operations’.Footnote 173

Women's experiences of peacekeeping life

There remains a desperate shortage of literature on women's experiences of peacekeeping, and participation in military life. The available data tells us that social isolation and high levels of scrutiny are the biggest challenges, which are the inevitable result of being the minority in an organisation.Footnote 174 According to Karame, Norwegian female soldiers described their experience of peacekeeping in South Lebanon as difficult and lonely, particularly during free time when their recreational interests did not coincide with their male counterparts.Footnote 175 Coping mechanisms employed by the female soldiers included monthly women-only meetings comprised of female soldiers and officers to discuss the issues they faced. In the UNMIL mission in Liberia, Karim and Beardsley found that women suffered similar feelings of isolation. Some reported pressure to dress less femininely; others tried to become more masculine to break into the all-boy networks.Footnote 176

Interviews conducted with female military personnel in 2019 found that women felt scrutinised by their colleagues during peace operations making it harder to blend in.Footnote 177 Conversely, in her research on an all-female police contingent, Lesley J. Pruitt found that female peacekeepers did not experience those feelings and felt very comfortable with their femininity.Footnote 178 More research is needed on intersectionality in peacekeeping operations, or what Joan Acker terms ‘inequality regimes’Footnote 179 and the effect this has on female military personnel's ability to perform their tasks. In peacekeeping this pertains as much to patrolling and enforcement as it does integration and mainstreaming.

Conclusion

This article has highlighted the practice of what we term sidestreaming in national militaries. We define sidestreaming as the practice, deliberate or unintentional, of sidelining women and relegating them to specialised spaces in international peace and security while attempting gender mainstreaming or increased gender integration. This practice effects the following results: (1) the sidelining of women in the military, which in turn negatively impacts retention, promotion, and recruitment; (2) the limited use of women in peace operations, or relegation to specialised spaces to the detriment of women's career development within the military; and (3) mainstreaming in its fullest sense as originally defined by the Windhoek Declaration and subsequent resolutions has yet to occur.Footnote 180 While access to all areas in the military has been opened up by many states, meaningful participation across all roles has not increased to the extent mainstreaming can be said to have occurred. In national militaries this means we still see women functioning in low-status positions and lingering in the lower ranks. In other words it could be said that women are continuing to perform hidden labour even within national institutions. Successful mainstreaming in the military context requires greater recognition of women's contributions and an equal opportunity mindset that doesn't automatically glorify combat. In peacekeeping, we find women are instrumentalised by national militaries, retained in specialised spaces in the field and used as an ‘organizational resource’.Footnote 181 We need to ensure that women are not solely being deployed in specialised spaces and furthermore that spaces occupied by women do not become feminised spaces that exacerbate gender divisions in the field and in military service. Despite demonstrating a rhetorical commitment to promoting 1325 UN peacekeeping has not been mainstreamed as envisioned by the Windhoek Declaration.

Currently the Canadian Government's ELSIE initiativeFootnote 182 is conducting large-scale research on women in national police and militaries to assess the impact of recruitment, retention and promotion on women in peacekeeping.Footnote 183 This project and our research indicates that many national militaries recognise that greater integration of women into the armed forces is necessary. As stated in the introduction, we do agree that researching women's experiences of the military is important and necessary. But we also see that the problem-solving approach to female integration taken by militaries, and indeed research on how to do this, is not tackling the larger question of how to alter the military mind-set. We offer two thoughts on this: (1) that gender mainstreaming is not going to be possible without some reform of the military itself using an approach that prioritises human security;Footnote 184 and (2) that future research on this topic will need to include men.

In regard to the first point: As states and militaries increasingly need to conceptualise security differently to deal with multiple non-traditional threats,Footnote 185 this article supports a vision of post-national cosmopolitan militaries that recognise the value of civilian tasks and the need to decouple violence, military practices, and combat skills from masculinity.Footnote 186 In this vision, civilian tasks and functions become more important and ethics of care and cooperation are highly valued.Footnote 187 Furthermore, while Enloe has acknowledged the contribution of non-military staff to the functioning of national militaries,Footnote 188 we argue here that the contribution of female military personnel also requires a status upgrade within militaries. This should help to alleviate the problem of sidestreaming whereby certain issue areas are gendered and undervalued as a result.

The path to reaching this goal is beyond the scope of this paper and requires more systematic research. But on our second point, we contend that to achieve all this, the focus of research cannot only be women. How men fit into this scenario is essential to research and understand in particular how they respond to the hyper-masculine norms perpetuated by the military. As Caroline Criado Perez notes, if we continue to treat women as niche (or minority or subcategory) and men as the default option, gender equality will not result. As such, conducting research on women only in the military context will also serve to perpetuate the gender issues = women's issues mentality that has a real danger of being ignored by those who need to pay the most attention to it.Footnote 189

Aside from the issue of how to integrate women more comprehensively into national militaries and peacekeeping, there remains a lack of systematic research on how women experience war and peace as combatants.Footnote 190 How do women manage security threats? What strategies and tactics do they draw on during combat? What do they prioritise when securing an area? What do they prioritise in their contribution to military service, war and peace? Knowledge of all this has implications for future peace operations, in particular the provision of gender sensitive security sector reform (SSR) and demobilisation, disarmament, and reintegration (DDR) programs in postconflict states. Understanding how women confront and deal with violence and conflict as agents in security institutions, will be a significant contribution to both academic researchers and policymakers interested in gender mainstreaming in security institutions and institutional reform.Footnote 191

Finally we offer some interim policy recommendations. Until now, gender has been dealt with by national militaries from an essentialist perspective. For national militaries to evolve, gender would need to be viewed through a constructivist lens, which as Laura Shepherd notes even ‘at the thin end of the constructivist spectrum’, views gender in part as a learned social behaviour.Footnote 192 Viewing gender from this perspective would enable armed forces to recognise that so-called feminine and masculine behaviours can be trained. In turn this might lead to a more gender-balanced military environment.Footnote 193 For meaningful participation to occur, we also suggest reducing or removing the need for lengthy combat experience to reach senior positions. Militaries need to find ways to reduce masculine hierarchies increasing the value of women's contributions in a way that normalises their presence at all levels and in all roles.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the three anonymous reviewers for their invaluable feedback on this article. In addition we thank the Leiden University Chair of United Nations Studies in Peace and Justice for the opportunity to present the first version of this article at a workshop entitled ‘Where Are the Women?’ hosted at Leiden University in December 2019.

Dr Vanessa F. Newby is an Assistant Professor at Leiden University and President of Women in International Security Netherlands (WIIS-NL) based in The Hague. Her research interests include women peace and security, human security, peacekeeping, humanitarian aid and disaster response, and the international relations of the Middle East. She is the author of Peacekeeping in South Lebanon: Credibility and Local Cooperation with Syracuse University Press (2018).

Clotilde Sebag is a researcher at the Institute of Security and Global Affairs at Leiden University. Her research interests include international security, intelligence and security; women, peace and security; and organised crime.