Abstract

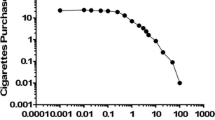

Problematic internet use (PIU) is of increasing concern to society and is correlated with negative behavioral and health issues. Human laboratory procedures to assess economic demand for internet use may be useful in translational efforts to better understand PIU and to assess potential treatments. One such procedure involves hypothetical purchases of access to internet use. Little is known about how such hypothetical purchases relate to actual behavior. In the current study, we assessed the correlation between measures of demand via an internet purchase task (IPT) and breakpoints on a progressive ratio (PR) schedule (n = 52). Participants responded on a computer-based task on an escalating work requirement that resulted in 30-s of access to their internet-enabled smartphone. We found a statistically significant correlation between demand intensity (Qo) and total responses (r(29) = .83, p < .001), and between Omax (maximum response expenditure) and total responses (r(29) = .34, p = .03) on the PR schedule. We did not find a relationship between measures of demand elasticity and measures of PR behavior. Because Omax is reflective of both demand and elasticity and Q0 is primarily influenced by demand alone, the results of this study indicate that demand intensity of internet use may be a better predictor of real-world behavior than other measures of demand. These results suggest that demand intensity for internet access may be a valuable proxy for behavior-based measures in the assessment and treatment of PIU.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Aboujaoude, E. (2010). Problematic internet use: An overview. World Psychiatry, 9(2), 85–90

Acuff, S., MacKillop, J., & Murphy, J. (2018). Applying behavioral economic theory to problematic internet use: an initial investigation. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 32(7), 846–857

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Author.

Amlung, M., Acker, J., Stojek, M., Murphy, J., & MacKillop, J. (2012). Is talk “cheap?” An initial investigation of the equivalence of alcohol purchase task performance for hypothetical and actual rewards. Alcoholism: Clinical & Experimental Research, 36(4), 716–724

Bickel, W. K., Johnson, M. W., Koffarnus, M. N., Mackillop, J., & Murphy, J. G. (2014). The behavioral economics of substance use disorders: Reinforcement pathologies and their repair. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 10, 641–677

Broadbent, J., & Dakki, M. A. (2015). How much is too much to pay for internet access? A behavioral economic analysis of internet use. Cyberpsychology, Behavior & Social Networking, 18(8), 457–461. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2014.0367

Cash, H., Rae, C. D., Steel, A. H., & Winkler, A. (2012). Internet addiction: A brief summary of research and practice. Current Psychiatry Reviews, 8(4), 292–298. https://doi.org/10.2174/157340012803520513.

Chase, H. W., Mackillop, J., & Hogarth, L. (2013). Isolating behavioural economic indices of demand in relation to nicotine dependence. Psychopharmacology, 226(2), 371–380. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-012-2911-x.

Doubeni, C. A., Li, W., Fouayzi, H., & Difranza, J. R. (2008). Perceived accessibility as a predictor of youth smoking. Annals of Family Medicine, 6(4), 323–330. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.841.

Epstein, L. H., Dearing, K. K., & Roba, L. G. (2010). A questionnaire approach to measuring the relative reinforcing efficacy of snack foods. Eating Behaviors, 11(2), 67–73

Friman, P., & Poling, A. (1995). Making life easier with effort: basic findings and applied research on response effort. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 28, 583–590

Gilroy, S., Kaplan, B., & Reed, D. (2020). Interpretation(s) of elasticity in operant demand. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 114(1), 106–115

Gilroy, S. P., Kaplan, B. A., Reed, D. D., Hantula, D. A., & Hursh, S. R. (2019). An exact solution for unit elasticity in the exponential model of operant demand. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 27(6), 588–597.

Grace, R., Kivell, B., & Laugesen, M. (2015). Estimating cross-price elasticity of e-cigarette using a simulated demand procedure. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 17(5), 592–598

Hales, A.H., Wesselmann, E.D., & Hilgard, J. (2019). Improving psychological science through transparency and openness: An overview. Perspectives on Behavior Science, 42, 13–31

Hashash, M., Abou Zeid, M., & Moacdieh, N. M. (2019). Social media browsing while driving: Effects on driver performance and attention allocation. Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology & Behaviour, 63, 67–82

Hayashi, Y., & Blessington, G. P. (2018). A behavioral economic analysis of media multitasking: Delay discounting as an underlying process of texting in the classroom. Computers in Human Behavior, 86, 245–255

Hayashi, Y., Friedel, J. E., Foreman, A. M., & Wirth, O. (2019). A cluster analysis of text message users based on their demand for text messaging: A behavioral economic approach. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 112(3), 273–289

Hayashi, Y., & Nenstiel, J. N. (2019). Media multitasking in the classroom: Problematic mobile phone use and impulse control as predictors of texting in the classroom. Current Psychology: A Journal for Diverse Perspectives on Diverse Psychological Issues. Advance online publication https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-019-00395-7.

Hursh, S. R (1978). The economics of daily consumption controlling food- and water-reinforced responding. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 29(3), 475–491

Hursh, S. R. (1980). Economic concepts for the analysis of behavior. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 34(2), 219–238

Hursh S. R., & Silberberg A. (2008). Economic demand and essential value. Psychological Review, 115(1), 186–198

Hursh, S. R., & Winger, G. (1995). Normalized demand for drugs and other reinforcers. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 64(3), 373–384

Jacobs, E., & Bickel, W. (1999) Modeling drug consumption in the clinic using simulation procedures: Demand for heroin and cigarettes in opioid-dependent outpatients. Experimental & Clinical Psychopharmacology, 7(4), 412–426

Johnson, M., & Bickel, W. (2006). Replace relative reinforcing efficacy with behavioral economic demand curves. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 85(1), 73–93

Kaplan, B. A., & Reed, D. D. (2014). Essential value, Pmax and Omax Automated Calculator [spreadsheet application]. Retrieved from: http://hdl.handle.net/1808/14934

Killeen, P. (2019). Predict, control, and replicate to understand: How statistics can foster the fundamental goals of science. Perspectives on Behavior Science, 42, 109–132

Ko, C., Yen, J., Chen, C., Yeh, Y., & Yen, C. (2009). Predictive values of psychiatric symptoms for internet addiction in adolescents: A 2-year prospective study. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 163(10), 937–943

Koffarnus, M. N., Franck, C. T., Stein, J. S., Bickel, W. K. (2015). A modified exponential behavioral economic demand model to better describe consumption data. Experimental & Clinical Psychopharmacology, 23(6), 504–512

Locey, M. L. (2020). The evolution of behavior analysis: Towards a replication crisis? Perspectives on Behavior Science, 43, 655–675

Locey, M. L., Jones, B. A., & Rachlin, H. (2011). Real and hypothetical rewards. Judgement & Decision Making, 6(6), 552–564

Mackillop, J., & Murphy, J. G. (2007). A behavioral economic measure of demand for alcohol predicts brief intervention outcomes. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 89(2–3), 227–233. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.01.002.

MacKillop, J., Murphy, J. G., Ray, L. A., Eisenberg, D. T., Lisman, S. A., Lum, J. K., & Wilson, D. S. (2008). Further validation of a cigarette purchase task for assessing the relative reinforcing efficacy of nicotine in college smokers. Experimental & Clinical Psychopharmacology, 16(1), 57–65

McLeod, D. R., & Griffiths, R. R. (1983). Human progressive-ratio performance: Maintenance by pentobarbital. Psychopharmacology, 79, 4–9

Moreno, M.A., Jelenchick L., Cox, E., Young, H., Christakis, D.A. (2011). Problematic internet use among US youth: A systematic review. Archive of Pediatric & Adolescent Medicine, 165(9), 797–805

Murphy, J. G. & MacKillop, J. (2006). Relative reinforcing efficacy of alcohol among college student drinkers. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 14(2), 219–227

Reed, D. D., Kaplan, B. A., Becirevic, A., Roma, P. G., & Hursh, S. R. (2016). Toward quantifying the abuse liability of ultraviolet tanning: A behavioral economic approach to tanning addiction. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 106(1), 93–106. https://doi.org/10.1002/jeab.216.

Roane, H. S., Lerman, D. C., & Vorndran, C. (2001). Assessing reinforcers under progressive schedule requirements. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 34, 145–167

Roma, P. G., Hursh, S. R., & Hudja, S. (2016). Hypothetical purchase task questionnaires for behavioral economic assessments of value and motivation. Managerial & Decision Economics, 37, 30

Roma, P.G., Reed, D.D., DiGennaro Reed, F.D. & Hursh, S. R. (2017). Progress of and prospects for hypothetical purchase task questionnaires in consumer behavior analysis and public policy. Behavior Analyst, 40, 329–342. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40614-017-0100-2.

Shahan, T. A, Bickel W. K., Madden, G. J., & Badger, G. J. (1999). Comparing the reinforcing efficacy of nicotine containing and de-nicotinized cigarettes: A behavioral economic analysis. Psychopharmacology, 147, 210–216

Smith, T., Cassidy, R., Tidley, J., Luo, Z., Le, C., Hatsukami, D., & Donny, E. (2017). Impact of smoking reduced nicotine content cigarettes on sensitivity to cigarette price: Further results from a multi-site clinical trial. Addiction, 112, 349–359

Sprong, M. E., Buono, F. D., Bordieri, J., Mui, N., & Upton, T. D. (2014) Establishing the behavioral function of video game use: Development of the video game functional assessment. Journal of Addictive Behaviors, Therapy, & Rehabilitation, 3(4). https://doi.org/10.4172/2324-9005.1000130.

Stafford, D., LeSage, M. G., & Glowa, J. R. (1998). Progressive-ratio schedules of drug delivery in the analysis of drug self-administration: A review. Psychopharmacology, 139, 169–184

Stein, J. S., Koffarnus, M. N., Snider, S. E., Quisenberry, A. J., & Bickel, W. K. (2015). Identification and management of nonsystematic purchase task data: Toward best practice. Experimental & Clinical Psychopharmacology, 23(5), 377–386

Zvorsky, I., Nighbor, T. D., Kurti, A. N., DeSarno, M., Naude, G., Reed, D. R., & Higgins, S. (2019). Sensitivity of hypothetical purchase task indices when studying substance use: A systematic literature review. Preventive Medicine, 128, 1–17

Availability of data and material

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Code availability

The code used in this article is available for download by the public on Github at https://github.com/isalau/PsychologyTool

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1

Participant Directions

The first part of this session will take approximately 30–45 minutes.

During this session, you’ll be presented with a number and a sliding scale. We’ll go over an example so you can see. You can choose to drag the mouse to the number on the sliding scale. Once you complete a certain number of these tasks, you can have access to your cellphone. The computer will tell you when you’ve earned access to your phone with a bell sound and the words “You now can access your phone for 30 s” on the screen. When your phone time is over, they’ll go away and the bell will sound again.

The response requirement (meaning how much work you have to do to earn your phone) is going to increase each time you complete a schedule. For example, the first time you might have to do 2 tasks to earn your phone and the next time it may be 4. You don’t have to complete these tasks if you don’t want to—you can choose to just sit if you would prefer. You will still earn SONA points or reimbursement if you choose to stop completing the tasks.

If you’re willing, during periods when you do not have access to your phone, please set it on the orange chair behind you. This is just to make sure you’re only accessing it during the allotted times. I will not interact with your phone at any time or watch what you choose to do on it- feel free to browse with it as you normally would when the computer tells you it’s okay.

When this part of the study ends, either the computer will tell you with a low tone (a gong sound), or I will end the session by knocking on the door. If you finish early, we ask that you still stay for the remainder of the 30 minutes. You can choose to stop the session at any time if you would not like to participate any longer. Remember, you don’t have to do any work if you don’t want to.

Do you have any questions? Would you like to practice?

Appendix 2

In the following survey, we would like you to imagine that you can buy 30 second access periods to your phone and all of its functions, apps, social media, and internet connectivity. Please answer honestly and thoughtfully. You may buy as many access periods as you’d like, and there are no negative consequences to your using your phone.

Assume that you will not have any other access to your phone or the internet today. Pretend that you cannot access the internet or social media through any other means today, other than what you purchase here. You can’t save up your time and use it another day. Everything you buy is for your own personal consumption within a 24-hour period.

Price per 30 s of phone use | How many 30 second periods of phone/social media access I would choose to buy |

|---|---|

$0.01 | |

$0.05 | |

$0.13 | |

$0.25 | |

$0.50 | |

$1.00 | |

$3.00 | |

$6.00 | |

$11.00 | |

$35.00 | |

$70.00 | |

$140.00 | |

$280.00 | |

$560.00 | |

$1,120.00 |

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Stinson, L.A., Prioleau, D., Laurenceau, I. et al. Correspondence between Responses on an Internet Purchase Task and a Laboratory Progressive Ratio Task. Psychol Rec 71, 247–255 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40732-021-00463-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40732-021-00463-0