Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic had a substantial impact on the historical criminal trend around the world. This study explores the early impact of COVID-19 lockdown on selected crimes in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Based on open data of the total number of arrests reported by Dhaka Metropolitan Police (DMP), an uninterrupted historical time series analysis is applied to evaluate the immediate impact during and after the official stay-at-home order due to COVID-19. Auto-regressive moving average (ARIMA) modeling technique was used to compute 6-month-ahead forecasts of the expected frequency of the total number of arrests for illegal arms dealing, vehicle theft, and narcotics trafficking in the absence of the pandemic. These forecasts were compared with the observed data from April 2020 to September 2020. The results suggest that the observed numbers of total arrests for vehicle thefts and illegal arms dealing are not significantly different from their predicted values. However, the observed frequency of the total number of arrests for illegal drug trafficking shows a steep upward trend, which is 75% more than that of the expected frequencies. Estimated results are used to recognize scopes and suggestions for future research on the relationship between crimes and the pandemic.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

After the first case of COVID-19 was reported in Wuhan, China, on December 31, 2019, the pandemic has spread over the world and quickly became a global crisis. As of October 14, 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard reported 38,002,699 confirmed cases including 1,083,234 deaths worldwide (WHO 2020). To combat the pandemic, global lockdown has been prescribed, restricting travels, and stay-at-home orders introduced a new phenomenon known as work from home.

While the primary focus of the stay-at-home order was to confine the pandemic, it can impose a significant impact on numerous socio-economic factors, which along with stagnating economic growth led to an upsurge in criminal activities (Cohen and Felson 1978). A couple of explanations can be suggested for this shift in criminal behavior, but the change in the opportunity structure is identified as the most feasible (Hodgkinson and Andresen 2020). The stay-at-home order is restricting people’s movements, making them more homebound; as a consequence, offenses like burglaries are supposed to plummet (Campedelli et al. 2020). On the other hand, as work and education have now shifted online, several new forms of crimes are becoming widespread, like cybercrime (Lallie et al. 2020). Restriction in movements may lead to offenses like violent crimes to increase (e.g., domestic violence, intimate partner violence), whereas robbery, thefts, serious assaults incidences might shrink (Bullinger et al. 2020; Pearson 2020).

Following the recommendations of WHO, Bangladesh began its complete lockdown on March 26, 2020, after the first case officially reported on March 8, 2020. However, after more than 2 months of restriction, the government of Bangladesh announced an easing of the COVID-19 official stay-at-home order from May 31, 2020 (Government of Bangladesh 2020). During the 65 days of the nation-wide lockdown phase, a COVID-19 response task force, comprising various social and law enforcement organizations, was active to monitor and handle the country’s situation. After lockdowns were eased, the country began to operate as normal with the enforcement of minimal or no social distancing and health guidelines. This study tries to shed light on the criminal behavior in Dhaka, the capital of Bangladesh, during and after the official lockdown period. Most of the literature focusing on the relationship between pandemic and crime are done from a developed country perspective and established variant outcomes. Only a handful of studies have explored the effect of the pandemic on the overall crime trend emphasizing developing nations, and the majority of these studies are the compilation of various print media reports (Ahmed et al. 2020; Bhuiyan et al. 2020). One probable reason for the insufficient empirical analysis is the fact that developing countries still suffer from the unavailability of authentic and updated crime data sources (UNODC 2019). This creates a natural knowledge gap on the effects of the lockdown due to COVID-19 on crime trends in terms of a developing nation. This paper tries to bridge the knowledge gap by analyzing crime trends during and after the official lockdown due to COVID-19 in Dhaka, Bangladesh.

For this study, monthly incidence reports of Dhaka Metropolitan Police (DMP) are used to explore crime trends in Dhaka. A time series dataset of the total number of arrests for three (03) types of offenses: guns and ammunition, vehicle theft, and illegal drug trafficking are created. Using monthly data for each series range from January 2012 to September 2020, this paper tries to estimate what would be the total arrest counts for each crime series without the pandemic and how that fluctuate during and after the official stay-at-home order. This is the first empirical analysis focusing on Bangladesh exploring how crime has changed during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Existing Evidence

Media outlets all over the world have been screaming out on the potential upsurge of various crimes due to coronavirus. Media activists and academics are also weighing in with their predictions. There has been significant evidence of a potential crime hike around the world associated with COVID-19 and the ensuing stay-at-home orders. Several mechanisms have been identified through which lockdown initiatives are likely to influence criminal offenses. The most pronounced one is the vigorous disruption of people’s daily routine, which may significantly alter financial conditions and provoke crimes. The effective stay-at-home regimes may also have a significant downward effect on certain crime types, e.g., burglary, street violence, and outdoor assaults (Eisner and Nivette 2020). On the other hand, this could enhance the incidence of domestic or intimate partner violence, which thrives behind closed doors (Piquero et al. 2020; Deluca et al. 2020; Pearson 2020; Usher et al. 2020).

To better understand the expected frequency of crime in the absence of official lockdown order, different time series analysis methods (ARIMA, SARIMA) are used in literature. Investigating data of daily counts of calls for service in Los Angeles (LA) and Indianapolis, Mohler et al. (2020) found a marginal decline in burglary and vandalism calls. Vehicle theft calls showed a significant increase in LA and an increase in domestic violence calls were reported in both cities. Analyzing the data on different crime types, Abrams (2020) investigated the before and after effects of stay-at-home order. The article found a significant drop in violent and property crimes after the stay-at-home order in 25 cities in the USA. There was also substantial variation in the overall crime rates across cities. Using historical crime data of 17 large US cities, Ashby (2020) forecasted the expected frequency of serious assaults in public, serious assaults in residences, residential burglaries, non-residential burglaries, motor vehicle theft, and stealing from cars in the early months of 2020. Applying the seasonal auto-regressive moving average (SARIMA) model, his results showed that even though city-weeks crime diverges significantly from historical averages, most crime changes were not statistically significant (Ashby 2020).

The net effect of the official lockdown on crime trends is uncertain as it varies by the nature of the crimes and the locations of origin. Using monthly violent crime (common assault, serious assault, sexual offenses, and breaches of domestic violence orders) data for Queensland, Australia, the monthly offense rate between February 2014 and February 2020 was analyzed (Payne and Morgan 2020). They used historical data to forecast March 2020 data and then compared the forecast to the actual crime that was recorded in March 2020. Results showed that in four violent crime categories, the actual rates did not differ from the forecasts, and in fact, the actual March 2020 crime was lower than the forecasts. Using an interrupted time series crime data from Vancouver in Canada, Hodgkinson and Andresen (2020) found evidence of a decline in total crime trend, especially for burglary (both residential and commercial), and vehicle theft. A similar trend in reduction in aggregate crime was found by employing data from the UK (Halford et al. 2020). The authors documented that intimate abuse, burglary, assault, and vehicle theft are the type of offenses that went down due to lockdown. Calderon-Anyosa and Kaufman (2021) used interrupted time series data from the Peruvian National Death Information System and found evidence of a decrease in homicides in Peru. First information report data from Bihar, India, showed that COVID-19 lockdown decreased aggregate crime by 44% (Poblete-Cazenave 2020). The explanatory analysis showed that the lockdown reduced domestic violence, burglary, robbery, kidnapping, and murder.

Since the pandemic situation is still evolving and there exists the complexity of potential interaction between numerous driving forces, the goal of this study is to make an initial evaluation of how the total number of apprehensions of different crimes (illegal arms dealing, vehicle theft, and narcotics trafficking) has changed during and after the official stay-at-home order in Dhaka. This study did not attempt to test specific practice of law enforcement but is an exploratory analysis to understand how the total number of arrests for different offenses fluctuates throughout the lockdown period.

Methodology

Data

Dhaka, the capital of Bangladesh, is the area of interest for this study. According to the United Nations—World Population Prospects, the current metro area population of Dhaka in 2020 was 21,006,000. This makes it the sixth-most densely populated city in the world. Public safety in Dhaka is maintained by Dhaka Metropolitan Police (DMP) with 50 stations and more than 34,000 personnel (Rabbi 2018). Like any other densely populated megacity, Dhaka city has experienced its fair share of diverse criminal activities. Depending on the period and crime type, the total crime rate of Dhaka city fluctuates. This paper uses administrative monthly crime data published by DMP, and this data is only available for Dhaka city. Each month DMP provides a publicly accessible incident-level extract of police records for different offense types.Footnote 1 This open-access data source allows monitoring of emerging crime trends which would be obscured in annual crime statistics bulletins produced by the government and other independent agencies.

The DMP mandates officers to record daily criminal activities along with crime types, detailed descriptions of the act (e.g., different types and number of guns and ammunition seized), number of total suspects, and number of total arrests. At the end of the month, DMP crime analysts upload monthly crime statistics on their website.Footnote 2 The DMP reports different types of crimes such as dacoit, burglary, homicide, guns and ammunition, drugs, women and child repression, kidnapping, theft, and other types of offenses. But this paper solely focused on three (03) types of incidents, illegal arms dealing, vehicle thefts, and illegal narcotics traffickingFootnote 3 because of the availability of historical data for these three offenses. A brief description of these types of offenses in the context of Bangladesh is given below:

-

1.

Illegal Ammunition

The Arms Act 1878 defines a comprehensive and broad definition of “arms” in Bangladesh. This includes firearms, bayonets, swords, daggers, spears, spearheads and bows and arrows, also cannon and parts of arms, and machinery for manufacturing arms. The Arms Act clearly outlines that if any person armed without legal authorization shall be punished with imprisonment for a prescribed term (Government of Bangladesh 1991).

-

2.

Vehicle Theft

This includes any kind of auto theft involving car, truck, and motorbike. Stealing from vehicles including auto parts are also pronounced as vehicle theft. The vehicle theft cases are mandated by The Penal Code 1860 in Bangladesh.Footnote 4

-

3.

Illegal Narcotics Trafficking

Bangladesh is situated in a vital location that can be treated as a transit by drug traders of countries like India, Pakistan, and Myanmar. Thus, drug prevention laws are very strict in the country. According to the Narcotic Control Act 1990, all types of production, processing, importing, exporting, buying, selling, or use of any kind of drugs are illegal. Also using any kind of alcohol to produce medicine is illegal unless the producer and as well as the consumer must have a license under drug policy. A detailed list of drug type and the punishment for the quantity-wise possession of that drug is given in the Appendix (Table 3). Despite these laws, the country struggles to control the drug issue. After the decade-long disappointing outcome in controlling drugs, Bangladesh government launched a “war” on drugs in 2018 following a proliferation of illegal substances in the South Asian nations (Paul 2018). In May 2018, the cabinet declared a zero-tolerance policy and approved capital punishment against illegal drug offenses. The government anti-narcotics crackdown led to the killing of nearly 300 people and arrests of about 25,000 across the country since May 2018 (Mahmud 2019).

To create monthly time series data, the total number of arrests for each of the three crimes was collected from DMP’s monthly incidence reports. The complete dataset consists of the total number of arrests for guns and ammunition, vehicle thefts, and illegal drug trafficking from January 2012 to September 2020, making the total number of months, N = 102. In Table 1, descriptive statistics for the total number of arrests for the individual categories are displayed. Despite the limitations of open data sources, articles on crime literature were found to rely on them to assess the periodic crime trend (Ashby 2020).

Econometric Approach

At the beginning of the analysis, a simple linear trend will help to understand the inherent trend of the raw data. The visual representation of the inherent trends of the series can be found in Fig. 1. Simple linear trends display a sharp plummet in vehicle theft and a steady increase in the arrest incidents for drugs. Arrest cases for illegal arms dealing seem to have a slight downward slope.

To understand the actual impact of COVID-19 on the overall crime, some estimates of how much crime would occur in the absence of the pandemic are required. If the expected number of offenses in absence of COVID is estimated, it can be compared with that of the actual number. The results can then identify whether the pandemic has intensified the overall crime trend or not. In the quest for a suitable forecasting model, this paper operationalizes an auto-regressive moving average (ARIMA) model for each of the three criminal offense categories. ARIMA models are a particular type of time series forecasting technique where AR indicates the own lagged values of regressed variables and MA is the linear combination of error terms at various times in the past (Enders 1995). The accuracy of future predictions substantially depends on the strength of past and future relationships among variables.

For each crime type, the observed values after March 2020 are excluded from the estimation process as from March 26, 2020, the official lockdown was implemented in Bangladesh. To implement ARIMA, each series need a statistical assessment of the presence of a unit-root or non-stationarity. The Augmented Dickey-Fuller (ADF) test is used to identify the stationarity of each series. The results of the ADF and Phillips-Perron test are given in the Appendix (Table 2). The series is used at the level if the unit-root test indicated stationarity. The next step is to specify the appropriate parameters of auto-regressive (AR) and moving average (MA), each of the series is examined using auto-correlation (AC) and partial auto-correlation (PAC) plot. The goal is to find the parsimonious and best-fitted model. Akaike Information Criteria (AIC) and Bayesian Information Criteria (BIC) are simultaneously considered for each model of each series. The lowest value of AIC and BIC indicates the best fit (Enders 1995). The detailed process of finding the final model is described in the Appendix (Tables 3 and 4).

Results and Discussions

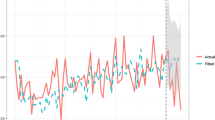

Figures 2, 3, and 4 show the final ARIMA specification to forecast both point estimates and their mean square errors (MSE). The MSE is used to calculate 95% confidence intervals from March 2020, official lockdown starts, up to and including September 2020. The observed frequency of each crime type and their corresponding forecast frequency based on the ARIMA models are presented in panel (a). In panel (b) of each figure, the model forecast with the associated 95% confidence interval is shown as two solid lines (orange-colored). Also shown on each figure is the date of the first day of official lockdown that took place due to COVID-19 in Dhaka, Bangladesh (which marks the end of the data with which the forecasts were made), together with the date on which the Government Bangladesh officially eased the stay-at-home order. The figures include the observed frequency of crime up to September 2020, the most recent available data at the time of writing.

Long-term trend and ARIMA forecast of guns and ammunitions. Note: Frequency of the number of arrests for illegal arms dealing during coronavirus pandemic compared to estimates of the number of assaults that would have occurred under normal conditions. L = official lockdown starts. E = officially lockdown eased

Long-term trend and ARIMA forecast of vehicle theft. Note: Frequency of the number of arrests for vehicle theft dealing during coronavirus pandemic compared to estimates of the number of assaults that would have occurred under normal conditions. L = official lockdown starts. E = officially lockdown eased

Long-term trend and ARIMA forecast for the illicit drug trafficking. Note: Frequency of the number of arrests for illegal drug trafficking during coronavirus pandemic compared to estimates of the number of assaults that would have occurred under normal conditions. L = official lockdown starts. E = officially lockdown eased

Before engaging in a discussion of the individual crime pattern, some important features of these graphs need to be identified. For each series, predicted point estimation and prediction interval are based on the data before March 26, 2020, in the graph identified as “L.” The final ARIMA specifications are used to forecast both point estimates and mean square errors (MSE). The MSE is used to calculate 95% confidence intervals from March 2020 up to and including September 2020 (panel b). For each series, a reference line “E” is added as an indication of May 31, 2020- officially easing of lockdown order.

Guns and Ammunition

Figure 2 shows that the frequency of arrests under illegal arms dealings was below in panel (a), which was estimated by final model ARIMA (0,0,1), but the frequencies were consistently outside the 95% confidence interval of the model (panel b). This suggests the observed variation was within what would be expected based on the frequency of arms dealings in previous years.

A sharp drop in the frequencies of both actual and forecasted is visible after stay-at-home order (L). But arrest cases seem to catch up after the restriction was eased (E). Overall, the frequency of serious assaults appears not to have systematically different between the actual and the forecasted ones. Theoretically, the results are expected given the number of times people staying outside decreased substantially during the pandemic. So, incidents in illegal arms handling seem to coincide with the daily movement of people.

Vehicle Theft

Figure 3 shows that the frequency of thefts of motor vehicles had divergent patterns across Dhaka city. The arrest frequency of thefts from vehicles shows significant reduction and decreases were particularly large: between March 26 and May 31. The major cause of the decrease in vehicle theft is likely to be the unavailability of unattended vehicles to steal from during pandemic lockdown. The distribution of vehicles may have changed because the number of times people outside their homes or in public places decreased substantially. This significantly affected people’s requirement to use private vehicles. After the government announcement of easement of restriction, the number of people outside increased drastically.

A similar trend with the frequency of arrests for vehicle theft is observed. In Fig. 3 (panel a), during the lockdown period, initially, the actual frequency was below the forecasted frequency. But in the later period, the actual frequencies were higher than the predicted one. Further research could therefore consider the driving cause of the changing distribution of vehicle thefts arrests cases.

Drugs Trafficking

Figure 4 shows the frequency of the arrests of illicit drug transactions, though there is a sudden drop at the beginning of the pandemic started in mid-February and the lowest frequency is in April. But the number starts to increase around May and keeps hiking till mid-June. During this period, the forecasted frequency is lower than the actual frequency and it remains lower till the end of the study period.

The main driver can be after the lockdown was initiated, DMP strictly controlled general movements, putting a natural restriction on the illicit drug trade. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) published reports citing the reason as a disruption in the supply chains of physical drug markets and the change of drug trafficking patterns and routes due to mobility restrictions, closed borders, and a decline in overall world trade (UNODC 2020).

However, Fig. 4 shows that, at least during the latter part of the mobility restriction order, there is a surge in arrest cases for illicit drug handling. After the government’s easing of stay-at-home order (point, E), a very sharp increase in the arrest cases for illicit drug trafficking is observed. Surprisingly, total arrest cases in July were reported 2369 whereas the ARIMA model’s prediction is 675, around 75% lower in the forecast. In the first few weeks of the pandemic, there was concern among lawmakers and metropolitan police departments to make restriction orders effective. When the restriction was eased, the latent demand for drug usage spiked and matched with the historical trend (Fig. 1). Several local print media outlets reported that due to transport restrictions during the pandemic, small and big consignments of narcotics are being transported using hearses, relief trucks, courier services, and other emergency vehicles (Islam 2020; Mollah and Saad 2020). Future research in this area might usefully recognize the appropriate strategies to reduce illegal drug trafficking in Dhaka. For instance, rather than the existing search for criminal approach, the government policy should be more emphasized on the intricate demand–supply-misuse dynamics surrounding drugs (Islam 2019).

Limitations

As with any analysis, this paper is not without its limitations. Because the crime series is created from compiling the monthly incidence reports of Dhaka Metropolitan Police (DMP), we are limited to only those types of criminal offenses that are recorded by the DMP. Moreover, the analysis covers Dhaka city only since the incidence reports during the pandemic period are available only for this city. Different offenses like serious assaults, homicide, burglary, vehicle theft, domestic violence, sexual violence, and cybercrimes have found to have a significant impact due to COVID-19 (Bullinger et al. 2020; Mohler et al. 2020; Hodgkinson and Andresen 2020; Ashby 2020; Abrams 2020). Due to the unavailability of the category-wise historical crime data, this paper considers only three crime types: guns and ammunition, vehicle theft, and illegal drugs.

Recent media reports in Bangladesh showing a surge in suicide cases during the pandemic period (Bhuiyan et al. 2020). Moreover, a notable upward trend in domestic and sexual violence is reported in print media (Tithila 2020). Unfortunately, this paper does not consider those offenses as the DMP incidence reports do not produce any periodic case histories for those types of offenses. In the future, extensive quantitative research for suicide and intimate partner violence cases needs to be conducted to validate the media claims. Additionally, the current findings should be validated against qualitative measures and successful approaches of other metropolitan cities in diminishing drug trafficking.

Conclusion

This study presents one of the first analyses on the extent to which crime has changed during the COVID-19 pandemic in Bangladesh. Specifically, it applies an iterative univariate ARIMA framework to three crime types (guns and ammunition, vehicle theft, and illegal narcotics trafficking) in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Using appropriate ARIMA specifications for each crime series, comparison between the actual and expected number of arrests was made. The government of Bangladesh mandated an official lockdown on March 26 and eased it on May 31. It is important to note that the results presented here are based on recorded arrest data for each crime. Forecast patterns of the number of arrests for each crime series are compared within and beyond this period.

Present research finds a significant drop in arrest cases in arms dealing and vehicle theft during the stay-at-home order period. But for the case of illegal drug trafficking, the numbers seem to climb up rapidly when the government eased the lockdown order. The actual total number of arrests in illegal drug trafficking significantly overpowered the predicted ones by around 75%. One probable explanation could be because of movement restrictions, the inherent long-term trend in narcotic trading was suppressed which hikes up right after the restriction was eased. Another important evidence on the surge of drug trading is identified in print media. During the pandemic, the law enforcement agencies were busy tackling the coronavirus restrictions; drug dealers have seemingly taken advantage of the consequent reduction in regular monitoring. Drug traders were found to use unconventional modes of transports in trafficking as all public transport except freight and emergency services were closed.

The present study focused mainly on the fluctuation in crime immediately after the official lockdowns that were imposed to slow the progress of the epidemic. One potential concern of the study is the arrest data during pandemic might be underreported, as police resources were diverted to enforce lockdowns, which was the case in many other developing nations. Thus, the actual number of arrests might be biased downwards. Future studies with access to more data will be able to understand how the patterns identified here will change over time, for instance, employing historical data from other megacities of developing countries.

Regardless of several limitations, and succeeding directions for future research, the present study contributes to the literature on exceptional events and crime from the context of an emerging economy. Cautious measures need to be taken in treating these early data as a definitive test of the crime-response to COVID-19. Extensive future research will be able to understand the relationships between coronavirus and crime trends. However, these early findings can certainly guide and shape greater scopes of future research.

Data Availability

Available upon request.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Notes

Monthly reports are available for different years starting from 2012 to September 2020. Retrieved from: https://dmp.gov.bd/crime_data_year/2020/.

The DMP monthly crime reports are open for general use, but the reports are written in Bengali language.

The paper considers only three (03) crimes as the DMP’s monthly incident reports are always incorporated crime statistics of these three types of offenses. In some months, DMP reported other crimes such as burglary and women and child repression. But those are no consistent over the year.

More details of this law can be found here http://bdlaws.minlaw.gov.bd/act-11/section-3235.html.

References

Abrams, D. (2020). COVID and crime: An early empirical look. U of Penn, Inst for Law & Econ Research Paper, (pp. 20–49).

Ahmed, S., Khaium, M.O., & Tazmeem, F. (2020). COVID-19 lockdown in India triggers a rapid rise in suicides due to the alcohol withdrawal symptoms: evidence from media reports. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 66(8), 827-829.

Ashby, M.P. (2020). Initial evidence on the relationship between the coronavirus pandemic and crime in the United States. Crime Science, 9(1), 16.

Bhuiyan, A. I., Sakib, N., Pakpour, A. H., Griffiths, M. D., & Mamun, M. A. (2020). COVID-19-related suicides in Bangladesh due to lockdown and economic factors: case study evidence from media reports. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 1–6.

Bullinger, L. R., Carr, J. B., & Packham, A. (2020). COVID-19 and crime: effects of stay-at-home orders on domestic violence (No. w27667). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Calderon-Anyosa, R., & Kaufman, J. (2021). Impact of COVID-19 lockdown policy on homicide, suicide, and motor vehicle deaths in Peru. Preventive Medicine, 143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2020.106331.

Campedelli, G.M., Aziani, A., & Favarin, S. (2020). Exploring the effect of 2019-nCoV containment policies on crime: the case of Los Angeles. arXiv preprint arXiv:2003.11021.

Cohen, L.E., & Felson, M. (1978). Social change and crime rate trends: a routine activity approach. American Sociological Review, 44(4), 588-608.

Deluca, S., Mitchell, B., Papageorge, N., & Coleman, J. (2020). The unequal cost of social distancing. Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center, https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/from-our-experts/the-unequal-cost-of-social-distancing.

Eisner, M., & Nivette, A. (2020). Violence and the pandemic. Urgent Questions for Research. HFG Research and Policy in Brief.

Enders, W. (1995). Applied econometric time series. New York: Wiley.

Government of Bangladesh (1991). Power to make rule as to licenses. Dhaka: Ministry of Law, Justice and Parliamentary Affairs, Section 17. Arms Act, 1878 (Act No. XI OF 1878).

Government of Bangladesh. (2020). Fighting with coronavirus: press briefing of Cabinet Secretary. Dhaka: https://cabinet.gov.bd/sites/default/files/files/cabinet.portal.gov.bd/notices/9abbd38f_f012_401c_a172_4654fc2ffada/corona%20press%20briefing.pdf. Retrieved September 12, 2020.

Halford, E., Dixon, A., Farrell, G., Malleson, N., & Tilley, N. (2020). Crime and coronavirus: social distancing, lockdown, and the mobility elasticity of crime. Crime Science, 9(1), 1–12.

Hodgkinson, T., & Andresen, M. (2020). Show me a man or a woman alone and i’ll show you a saint: changes in the frequency of criminal incidents during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Criminal Justice, 69 101706.

Islam, N. (2019). War on drugs: the case of Bangladesh. Harvard Public Health Review, 25, 1-4.

Islam, N. (2020, June 24). During the coronavirus period, drugs were also transported in the Hearse (in Bangla). Daily Prothom Alo, pp. 6.

Lallie, H.S., Shepherd, L.A., Nurse, J.R., Erola, A., Epiphaniou, G., Maple, C., & Bellekens, X. (2020). Cyber security in the age of COVID-19: a timeline and analysis of cyber-crime and cyber-attacks during the pandemic. arXiv preprint arXiv:2006.11929.

Mahmud, F. (2019). Over 100 drug dealers surrender in Bangladesh crackdown. Al Jazeera. Retrieved December 21, 2020, from https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2019/2/16/over-100-drug-dealers-surrender-in-bangladesh-crackdown.

Mohler, G., Bertozzi, A., Carter, J., Short, M., Sledge, D., Tita, G., . . . Brantingham, P. (2020). Impact of social distancing during COVID-19 pandemic on crime in Los Angeles and Indianapolis. Journal of Criminal Justice, 101692.

Mollah, S., & Saad, M. (2020). Lax surveillance amid Covid-19 crisis: narcos active again. The Daily Star. Dhaka, Bangladesh. Retrieved October 20, 2020, from https://www.thedailystar.net/backpage/news/lax-surveillance-amid-covid-19-crisis-narcos-active-again-1903033.

Paul, R. (2018). Bangladesh sets death penalty for drug offences in draft law. (C. Fernandez, Ed.) REUTERS. Retrieved December 16, 2020, from https://www.reuters.com/article/bangladesh-drugs/bangladesh-sets-death-penalty-for-drug-offences-in-draft-law-idUSL4N1WO2TS.

Payne, J., & Morgan, A. (2020). COVID-19 and violent crime: a comparison of recorded offence rates and dynamic dorecasts (ARIMA) for March 2020 in Queensland, Australia. https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/g4kh7.

Pearson, E. (2020, April 3). Family violence calls drop amid fears victims can’t safely seek help while in lockdown. The age. Retrieved September 16, 2020, from https://www.theage.com.au/national/victoria/family-violence-calls-drop-amid-fears-victims-can-t-safely-seek-help-while-in-lockdown-20200401-p54fzq.html.

Piquero, A., Riddell, J., Bishopp, S., Narvey, C., Reid, J., & Piquero, N. (2020). Staying home, staying safe? A short-term analysis of COVID-19 on Dallas Domestic Violence. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 601–635.

Poblete-Cazenave, R. (2020). The impact of lockdowns on crime and violence against women – evidence from India. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3623331 or https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3623331.

Rabbi, A.R. (2018). DMP opens 50th police station at Hatirjheel. Dhaka Tribune. Dhaka, Bangladesh. Retrieved October 20, 2020, from https://www.dhakatribune.com/bangladesh/dhaka/2018/07/08/dmp-opens-50th-police-station-at-hatirjheel.

Tithila, K.K. (2020). MJF: 13,494 women, children faced domestic violence during Covid-19 lockdown. Dhaka Tribune. Dhaka, Bangladesh. Retrieved October 20, 2020, from https://www.dhakatribune.com/health/coronavirus/2020/06/10/mjf-13-494-women-children-faced-domestic-violence-during-covid-19-lockdown.

UNODC. (2019). Global study on homicide. Viena: 2019.

UNODC. (2020). Covid-19 and the drug supply chain: from production and trafficking to use. United Nations Office On Drugs And Crime. https://www.unodchttps://www.unodc.org/documents/data-and-analysis/covid/Covid-19-and-drug-supply-chain-Mai2020.pdf. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

Usher, K., Bhullar, N., Durkin, J., Gyamfi, N., & Jackson, D. (2020). Family violence and COVID-19: increased vulnerability and reduced options for support. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing.

WHO (2020) Who coronavirus disease (covid-19) dashboard. https://covid19.who.int/.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The author declares no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rashid, S. Impact of COVID-19 on Selected Criminal Activities in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Asian J Criminol 16, 5–17 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11417-020-09341-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11417-020-09341-0