Abstract

Spaces occupied by organised crime are usually kept secret, hidden, invisible. Japanese criminal syndicates, the yakuza, made instead visibility a key feature of the spaces they occupy through an overt display of their presence in the territory: in the past, a yakuza headquarter could have been instantly recognised by the crest and group name emblazoned on the front wall. However, recent changes in legislation have restrictively regulated these spaces, and the hygienisation of central neighbourhoods that used to be vital loci of yakuza activity has eroded the visibility of the groups. The intensification of the neoliberal drive took these processes to the extreme: political élites are urging to hide the yakuza from international scrutiny. Meanwhile, gentrification and temporary fortification of big cities have already changed the urban landscape and expelled elements of visual disturbance: marginal and dangerous ‘others’ such as the yakuza and the homeless. This article explores the relationship between organised crime and (in)visibility through the unusual case of a criminal group that ironically strives for visibility, and aims to investigate the socio-spatial consequences of the invisibilisation of the yakuza. Based on interviews and institutional documents, this article focuses on the wards of Kabukichō (Tokyo) and Nakasu (Fukuoka) – traditionally spaces of yakuza presence – examining how the increasing grip of the politics of surveillance over urbanscapes and the consequent spatial displacement of the yakuza induced a change in the yakuza’s relationship with their surroundings. As a result, it is argued, this is further contributing to the emergence of new forms of crime challenging the yakuza’s historical monopoly of the underworld.

Similar content being viewed by others

‘The morning light doesn’t suit the yakuza’

(Hatsukoi – Miike Takashi)

Introduction

The Japanese yakuzaFootnote 1 are included amongst the most archetypical, long-lasting criminal groups in the world. Indeed, they share several features with criminal organisations such as the Italian mafias, the Chinese triads, and the Russian vory v zakone – e.g. being a confederation of hierarchically organised groups, having bodies of coordination for dispute resolution, and appealing to a code of higher values based on honour, loyalty, and obedience (Paoli 2003). However, they stand apart in terms of their use of secrecy and visibility. Mafia-type associationsFootnote 2 generally negotiate between the two: they can either remain secret while maintaining their presence perceptible among their surrounding communities through threats and omertà, or they can be both secret and invisible, leaving the community unaware or suspicious of their existence (Sergi 2017). Yet, the yakuza are neither secret nor invisible; in fact, their levels of visibility are unprecedented if compared to those of any other organisation. As a non-secret criminal organisation, they can afford to have offices and headquarters officially registered by the police-related Public Safety Commission, they organise public events for both adults and children, and they are the subject of gossip in specialised magazines that can be bought in every corner shop throughout Japan.

In this sense, Japanese criminal syndicates not only turned visibility into a key feature of their public image, but they used their presence in the territory as an overt display of power aimed at the population as well as the institutions. Nevertheless, since the 1990s, the government implemented a series of changes in legislation that have increasingly regulated the spaces of the yakuza in the urban landscape. In most recent years, this tendency was accompanied by plans of hygienisation of central neighbourhoods (famously, night-time entertainment centres such as Kabukichō and Goldengai in central Tokyo), a process spurred by the organisation for the Olympics (Kiso 03/10/2017). Therefore, on the one hand politicians are pursuing an agenda aimed at the hiding of the yakuza from international scrutiny in order to maintain the image of Japan as the ‘safest country in the world’ (Shushōkantei 2016). On the other hand, gentrification and temporary fortification of big cities are leaving their marks on urban landscapes. The consequence is the expulsion of elements of visual disturbance: negligible individuals such as the yakuza and the homeless.

This article explores the relationship between crime and (in)visibility through the unusual case of a criminal group that paradoxically strives for visibility, and aims to investigate the socio-spatial consequences of the recent invisibilisation of the yakuza. Competing factors such as an increasing state surveillance, neoliberal drives towards hygienisation and privatisation of public urban spaces, and severe anti-yakuza regulations aimed at the spatial displacement of the yakuza’s activities and offices, resulted in a detrimental impact on the power of the yakuza – especially in light of their historical use of visibility as a tool of social capital and extra-legal governance. However, as it will be argued, this phenomenon did not result in less crime and better social conditions, but rather in a more criminogenic environment that favoured the emergence of novel forms of crime (such as hangure and Chinese-led gangs),Footnote 3 which together contributed to a general state of social crisis. The article starts with an overview of how the yakuza’s presence has historically taken hold in urban spaces, and explains how high levels of visibility were used by the yakuza to meet their ends. It proceeds by analysing the limitations imposed to the yakuza’s spaces through the 1991 Bōryokudan Taisakuhō (hereafter Bōtaihō) and the Bōryokudan Haijojōrei (hereafter Bōhaijōrei), and by discussing the impact of these policies on two case studies, the wards of Kabukichō (Tokyo) and Nakasu (Fukuoka). Finally, the article concludes how these phenomena had an impact on the current situation of criminality within Japanese society at large.

Methodology

Given the paucity of information on the yakuza, the present article relied on archival research, previous fieldwork, and ad-hoc interviews. Data on anti-yakuza laws and regulations (national and prefectural) have been extracted and translated from the official Japanese texts: these are all available online through official channels, and consist of national laws, police documents, and local newspapers. As it is often the case when studying organised criminal groups, the qualitative part of the research represented a more challenging task: creating connections with members of the underground is often difficult and time-consuming; however, in this case, access to participants was possible due to previous connections established in the fieldwork conducted by one of the authors between 2017 and 2018 in Japan. The knowledge acquired during this previous fieldwork is an integral part of the present paper. However, new interviews targeting the main question of the yakuza in relation to urban spaces were deemed necessary. For this purpose, five specific interviews were carried out between February and August 2020, taking advantage of the connections formerly built. Given the Covid-19 emergency, it has not been possible to carry out research in loco, and interviews were thus conducted via digital platforms (e.g. email, Skype, Line). The interviews were semi-structured, and touched upon a series of issues pertaining the current analysis such as presence/visibility of the yakuza in either Kabukichō or Nakasu (according to the expertise of the interviewee), the concomitant rise of new forms of crime in the same areas, and changing dynamics of the yakuza’s economy. Digital encryption systems have also been employed for a higher level of security. Participants were chosen for their knowledge of the yakuza underground and their involvement with the two geographical areas of the case-study: these included Miyazaki Manabu, journalist and son of a yakuza boss, Okita Garyō, current journalist and ex yakuza member, Hirosue Noboru, one of the most active journalists and researcher in the field of the yakuza, Yabu Masataka, ex-investigator at the Hakata police department and current member of an anti-yakuza centre, and the boss of a large yakuza group (see Appendix). The comprehensive approach of the respondents, their first-hand knowledge of the issue, and the variety of expertise across the interviewees mitigated the shortcomings of having a limited number of participants, especially in light of the sensitive nature of the information provided. Informed consent was obtained by all participants, and anonymity has been granted to the person currently involved in the yakuza. All participants were informed of the research objectives and of the ways in which the data collected would have been used. As often done in fieldwork with organised crime, the reliability of the accounts was corroborated by comparing information with governmental data and through the observation of patterned responses. This method in particular is an informal but nevertheless valid way of confirming the reliability of the collected information (Zhang and Chin 2002). As it will be shown below, the very methodology of this research has been affected by the central issue of the present article; indeed, the high visibility of the yakuza was a key feature for the possibility of reaching out to high-ranking officials and people close to the institution itself, to the point that they were willing to share information via digital technologies.

Theoretical framework: territory, visibility, and neoliberalisation

The yakuza are usually considered as one of those particular forms of organised crime which can be defined as mafia-groups in the terms posed by Diego Gambetta (1993:1), who argues that what characterises the mafia is that they produce, promote, and sell private protection. This view is shared by scholars of organised crime such as Letizia Paoli (2002), who adds that these organisations, which can collectively be defined as ‘mafia-type associations’, cannot be reduced to their participation in illegal activities: since they pre-existed the formation of modern illegal markets, they are not shaped by such dynamics. In fact, their ideological framework, structure, and activities are driven by a logic of profit and power (Sergi 2017). The illegal protection and associated forms of extra-legal governance that these groups are able to provide to citizens as well as businesses is still the core of the activities of mafia-type associations (see Campana 2011; Varese 2011). Given that the State is the usual provider of protection to its citizens (Skaperdas 2001), there is a continued struggle to affirm its superiority on the mafia groups present in the national territory, either through collusion with political élites such as in Calabria (Sergi 2015) or via more violent means such as in Mexico (Diaz-Cayeros et al. 2011). This tends to happen in states where there are flaws in the enforcement of property rights, which leave space for the emergence of agencies that capitalise on alternative private ordering. As Milhaupt and West (2000) eloquently argue, areas of rights enforcement – such as bankruptcy, debt collection, landlords and tenants issues, shareholders rights, dispute intermediaries, financial repression, and entrepreneurial finances – present ineffective regulations that provide fertile ground for alternative dispute resolutors such as the yakuza. In this sense, their levels of visibility are instrumental in identifying them as firms that are able to provide protection and to issue credible threats of violence.

Indeed, a certain degree of visibility is an essential feature for mafia-type associations aspiring to provide illegal governance. Although mafia-type organisations must maintain high levels of secrecy in order to protect their activities and their organisation from state disruption, this must be balanced with their need for visibility (Catino 2019). Social capital is institutionalised through the application of a collective name, but this name must be acknowledged by the community for social capital to be effective. By claiming affiliation to the collective name, all organisation members are granted the backing of the collectively owned capital and are thus able to obtain benefits from external actors (Bourdieu 1986). Similarly, members of mafia-type organisations take advantage of their collective name to build a reputation and gain security (Sciarrone and Storti 2014). Therefore, some degree of recognition is necessary for a criminal group to be effective and successfully engage with the community in which they act. However, this recognition must remain at work at a local and informal level, and in particular avoid indiscrete ears – such as those of the law enforcement. Thus, mafia-type organisations face a paradox: while they have to disseminate information about themselves in order to maintain their social reputation, they must preserve a certain degree of secrecy, with the risk of miscommunication (Gambetta 2009). In the case of the yakuza, however, secrecy is negotiated in different terms, as it will be discussed later.

Another crucial aspect to take into account in our current analysis of the visibility of organised crime groups is the impact of neoliberalism, especially in relation to two distinct – yet entangled – neoliberal prerogatives: seduction and policing. As for the former point, criminological scholarship has discussed how criminal organisations are able to take up new opportunities for misconduct as provided by the neoliberal system, which create criminogenic asymmetries that offer illegal opportunities, create reasons to take up such opportunities, and establish loopholes that allow criminals (both white-collar criminals and mafia-type associations) to take advantage of them (Passas 1999; Reiner 2007). The socio-political consequences of neoliberalism (i.e. inequality, competitiveness) produce many adverse social consequences that are directly associated with crime (Wilkinson 2005). In this sense, economic dominance leads to higher rates of crime through both structural and cultural mechanisms. The former involves non-economic institutions becoming subservient to the economy and losing their capacity to exert external control and regulate behaviour, while the latter pertains to the dismissal of considerations of collective order and mutual obligations, as well as the deterioration of political and social values (Messner and Rosenfeld 2000). On a cultural level, the stress placed on financial achievement that lies at the core of neoliberalism is deemed to also impact upon the acceptability of engaging in criminal behaviours as a means to accrue monetary success. The ideology of prosperity for all members of society has proliferated all over the globe through neoliberalism and globalisation, which increasingly create means-ends discrepancies and, simultaneously, weaken normative standards and regulatory controls. Since the chances of attaining these socially constructed material goals through legal methods are relatively scarce, adopting a criminal or unethical approach to achieve these ends appears to be more realistic (Passas 2000). There is, however, a further dimension of neoliberal seduction that must be taken in account for the purpose of the current analysis, namely the appeal generated by the infiltration of corporate power in public spaces. This phenomenon is evident in Japan since the late 1980s, when a series of formerly public spaces (as Daiba, Makuhari New Town, and Yebisu Garden Place) have been turned into revenue-generating hotspots for corporate capital circulation (Cybriwsky 1999).

This leads us to the second neoliberal prerogative: policing, which in the context of urban space translates into the privatisation of surveillance. For example, within the neoliberal framework, the vast majority of security cameras are privately owned and authorities can easily access privately collected data since these are not strictly regulated by privacy laws (Murakami Wood et al. 2007). Under neoliberal governance, the private sector thus rhizomatically extends the formerly centralised domain of state surveillance – what Michel Foucault (1995) envisioned as discipline society – into a decentralised net of power poles which perform the tasks of policing and seducing simultaneously. This new shape of dominance, eloquently discussed by Gilles Deleuze in his definition of ‘societies of control’ (1992), guarantees an even higher degree of subjectification, as individuals comfortably accommodate regulatory mechanisms as they are constantly driven by the seductive lure of commodity fetishism in the now privately owned and surveilled spaces of the city.

In reshaping the urban territory and individuals’ affective relations to it, neoliberalism also forces organised crime groups to readjust their behaviours accordingly. However, this does not necessarily represent an obstacle for most of them. In fact, while allegedly strengthening its grip on street criminality through harsher regulations as a way to preserve a hygienic urban façade, the neoliberal prerogative of deregulation paves the way for new opportunities to organised crime groups, which can exploit the ‘loose grip’ over systemic corruption that is guaranteed in order to favour the liberalist proclivities of the economic élite (Wacquant 2009). The result is an exacerbation of social inequality: on the one hand, neoliberalism produces criminogenic environments in which white-collar crimes can thrive; on the other hand, these very environments reinforce that class differential which renders street crime the only possible outlet for the most disenfranchised strata of the population, which in turn keep performing the criminal labour that is necessary for the survival of organised crime at the margin of the city. In other words, visible street criminality is not eradicated, but it is somehow displaced: the city becomes a fluid arena in which the borders between what is demanded to be visible and what is deemed to remain invisible are continually renegotiated according to the needs of capital accumulation. In order to discuss these phenomena in the distinct case of contemporary Japanese organised crime, let us turn back to the onset of the yakuza in Japan, and in particular to the development of their (in)visible presence in the Japanese urban landscapes.

Historical background: how the yakuza inhabited urban spaces

Throughout history, the yakuza developed mechanisms of adaptation in order to cope with changing social and legal scenarios, as scholars have pointed out (Ino 1999; Hill 2003; Kaplan and Dubro 2003; Mizoguchi 2011; Miyazaki 2010). While considering these wider transformations, this section also examines the ways in which the yakuza came to be a visible feature of urban spaces across Japan through their connection with the semi-legal night-time economy, as well as their legal spaces (offices and yakuza-related companies). This section thus focuses on the main turning points of the history of the yakuza in the cities, as a critical account of the history of the yakuza goes beyond the scope of the present article.

The first step of the intertwined history of the yakuza and Japanese urban spaces dates back to the turn of the century, when the Restoration of the Meiji period (1868–1912) engendered a process of industrial development in the cities, which grew in size to accommodate the workforce from the countryside. The yakuza, until that moment still organised in small groups dealing with gambling (bakuto) and peddling (tekiya), adapted to the new urban environment. As Miyazaki (2008: 42) puts it: “The modern yakuza is born out of the modern city”. The plan of the government of potentiating the army as well as the industrial sector gave great impulse to the coal industry. Coal was transported by boat, leading to the formation of groups (gumi) of boatmen that were responsible for leveraging mine owners (ibid.). The rapid growth of the city, in particular big cities, meant an increased need of casual labourers for construction jobs, which were also organised by yakuza leaders (Kaplan and Dubro 2003). The swiftly increasing city population put immense pressure on law-enforcement, which was still a newly-formed, disorganised institution (Miyazaki 2008), and contributed to a heightened demand for extra-legal forms of protection. The formation of groups of workers in the construction industry and in the docks – two sectors highly infiltrated by the yakuza – and a weak police force provided many opportunities to yakuza groups in the cities. As for the traditional businesses – gambling and peddling – the hidden hideaways and private dens of the newly organised city offered places for the bakuto to continue their activities. As law enforcement became less tolerant of gambling, many bosses opened legitimate shops to act as fronts for their rackets (Kaplan and Dubro 2003). Furthermore, in this period tekiya were given legal authorization to operate their stalls in the commercial streets of the cities, strengthening their social position and allowing them to blend with other shopkeepers (Mizushima 1986). The increase of the population also led to the opening of restaurants and, in general, of the entertainment industry: yet another sector in which the yakuza became heavily involved (Miyazaki 2008). The spatialisation of the yakuza in the urbanscape of industrialised Japan wound through the streets of the new cities, but was still hidden to some extent. At this juncture in time the yakuza had not yet become a semi-institutionalised collective of criminal syndicates.

After the turmoil of the war, yakuza groups are commonly believed to have reorganised to supply goods and services that the State was not able to guarantee. Indeed, almost simultaneously to Japan’s capitulation, yami-ichi (black markets) emerged. This underworld was perpetually violent and could not be controlled by the Occupation forces, which bestowed policing powers to the only ones able to organise such a space: the yakuza. In the absence of a formal economy, black markets represented the only alternative (Dower 1999). The collaborative relation with the authorities is believed to have allowed the yakuza to become involved with the reconstruction, too: most construction companies had strong relations with yakuza groups, and many of them were so similar to yakuza gangs (they were both called gumi and had political influence) that they were almost indistinguishable. According to the Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers (SCAP) report, three of the fourteen-million-people labour force in Japan were related to the yakuza (Kaplan and Dubro 2003). The US forces had ostensibly no intention of targeting organised crime since they were not a priority and they were often fervent rightists and anti-communists, a good enough reason to leave them alone (ibid.). At the same time, the presence of the American military seems to have smoothened the infiltration of the yakuza also in those areas where there was a high demand for entertainment. This was the case, for instance, of the neighbourhood of Roppongi, occupied by the American army until 1952. The ward became one of the most fashionable places for leisure activities and night-life, thus catalysing the enthusiasm of a Japanese youth craving for a renewed sense of entertainment after the trauma of the war (Yoshimi 2003). It is not surprising, thus, that Roppongi became another hotbed of yakuza activity; in a sense, the yakuza managed to gain benefits from both sides of the American military presence in Japan. Indeed, due to the weaknesses of the SCAP-controlled democracy, urban reconstruction could only be achieved through the support of unofficial groups, able to police and impose order, take part in the rebuilding, and, in some instances, even in tax collection (Murakami Wood et al. 2007). Therefore, it can be argued that during the immediate postwar the yakuza managed to heighten their visibility. In fact, many yakuza groups consolidated in a hierarchical structure solid enough to entertain connections with the authorities as well as with economic actors, while also enforcing order in the disordered black markets. As a result, they were able to increasingly manifest themselves in the streets of many Japanese cities.

The unrest of the immediate postwar was followed by a period of political protests and conflicts. The yakuza, traditionally on the extreme right of the political spectrum, accepted to lend their muscle to stifle the dissent movements, and their already intertwined relationship with politicians became closer. In 1963, yakuza membership reached 184,000, including many shop owners and operators of entertainment businesses that joined local yakuza gangs. The national economy was starting to recover, and bar and restaurant owners, craving for minimising risks and maximizing profits, were keen to affiliate (Ino 1999). The golden period of the yakuza continued throughout the 1970s and the 1980s. By the time the 1980s’ economic bubble started to inflate, the yakuza had already accumulated millions of dollars in their coffers taking advantage of lax fiscal regulations and investments in real estate and stock markets. Yakuza groups upgraded to big business, running multi-million-dollar construction and entertainment companies. As a result, the yakuza were able to extend their control over wider spaces of the city. The Yamaguchi-gumi started their expansion towards Tokyo, breaking the unofficial pact that sanctioned the capital as turf of the Inagawa-kai and Sumiyoshi-kai, while Kobe and Osaka as Yamaguchi-gumi territory. To encourage this expansion, members of the Yamaguchi-gumi would receive up to $10,000 to start businesses in Tokyo, plus monthly payments of between $1500 and $2000. By 1990, the Yamaguchi-gumi had opened more than forty offices in the capital, operated by five-hundred members (Kaplan and Dubro 2003). Noticeably, such diffusion was also possible thanks to a narrative promoted by the yakuza themselves centred on Japanese traditional values, epitomised by the ninkyō-dō (the ‘chivalrous code’ linking back to a romanticised samurai imagery). This public image was fostered in conjunction with active participation to the life of the local communities, and participation in aid relief after national and regional catastrophes, including the tragic Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami (Rankin 2011). This did not only help the yakuza gain consensus among local communities, but also smoothened their infiltration within the urban fabric of the cities.

However, in 1985 a long and violent dispute ensued within the Yamaguchi-gumi, which sanctioned the beginning of a series of minor violent struggles in the years to follow, culminating in the so-called Hachiōji war (Miyazaki 2010; Ino 1999). This seems to have been one of the main reasons for the introduction of the first anti-yakuza legislation, the Bōtaihō, promulgated in 1991 and enforced in 1992, which represented a crucial step in the regulation of yakuza activities and spaces (Hill 2003). Indeed, according to Miyazaki Manabu (2010), this legislation restricted the yakuza’s access to the legal market, thus sanctioning their turn towards a more mafia-like behaviour, characterised by a less visible presence on the urban territory. The next sections trace in detail the impact of the spiral of increasingly punitive anti-yakuza regulations on the visibility of the yakuza from the Bōtaihō to the present day.

Turning the screw: visibility (de)regulated

The Bōtaihō (1991) represents the first law aiming at restricting the activities of the yakuza. This law also includes restrictions on yakuza spaces: it prohibits the use of offices during gang struggles if there is a risk to nearby residents (Bōtaihō, art. 3, para. 15), but the limitations may be extended if the risk continues even after the end of the struggle (Bōtaihō, art. 3, para 15.2). When these orders are issued, the manager of the office must ensure that entrance and exit doors are situated in visible places, and a mark specified by the rules of the Public Safety Commission – which states that the manager of the office has received the order of limitation of use – must be affixed (Bōtaihō, art. 3, para. 15.4). This law also manages territorial matters in peaceful times by regulating the spaces that can be occupied by the yakuza. In particular, bōryokudan members cannot display signs or objects that instil a sense of uneasiness to residents or passersby, as regulated by the Public Safety Commission (Bōtaihō, art. 4, para. 29), and access to the premises must be allowed to police officers for on-site inspection when determined by the Public Safety Commission (Bōtaihō, art. 4, para. 33). A further aspect to keep in consideration is that, following the enforcement of the Bōtaihō, the perception of the yakuza amongst common citizens gradually began to shift from a (semi)legitimate organisation to an illegitimate force of society. The yakuza started to be referred to as ‘violent groups’ (in Japanese, bōryokudan), a definition strongly opposed by yakuza groups, which insist that they are different from common criminals. The Yamaguchi-gumi rejected the law altogether and claimed it went against the right of association and the principle of equality before the law, but these claims did not find support amongst common citizens (Miyazaki 2010).

The second turn of the screw in terms of the impact to the visibility of the yakuza arrived in 2010/2011Footnote 4 when the Fukuoka prefecture introduced the Bōhaijōrei, which paved the way for the introduction of similar ordinances across Japan over the following year. Since in this article we consider the spatial displacement of the yakuza in Tokyo and Fukuoka, let us analyse the Bōhaijōrei as introduced by these two local governments. In both cities, the Bōhaijōrei present similar restrictions with regard to spaces and buildings. For example, an estate which leases a building must make sure that it will not be used as a yakuza office (Tōkyō-to Bōhaijōrei 2011, hereafter TB Ch. 3 art. 19). In the case in which an estate owner becomes aware that the rented property will be used as a yakuza office, they must make sure that the contract is not enforced (TB Ch. 4 Art. 20). Furthermore, there are a series of restrictions as to where a yakuza office can be established and operate: yakuza headquarters cannot be located within 200 m from schools (universities excluded) (Fukuoka-ken Bōhaijōrei 2010, hereafter FB Ch. 3 Art. 30.1; TB Ch. 4 Art. 22.1), courts of justice (FB Ch. 3 Art. 30.6; TB Ch. 4 Art. 22.2), children welfare institutions or children counselling centres (FB Ch. 3 Art. 30.2; TB Ch. 4 Art. 22.3), young offenders institutions (22.4), juvenile classification homes (FB Ch. 3 Art. 30.7; TB Ch. 4 Art. 22.5), community centres (FB Ch. 3 Art. 30.5; TB Ch. 4 Art. 22.6), libraries (FB Ch. 3 Art. 30.3; TB Ch. 4 Art. 22.7), museums (FB Ch. 3 Art. 30.4; TB Ch. 4 Art. 22.8), and probations offices (FB Ch. 3 Art. 30.8; TB Ch. 4 Art. 22.9). In addition to those spelled out in the preceding items, the list includes those facilities that need to preserve a good environment to promote the healthy development of the youth in the surrounding area, as specified by the Public Safety Commission (FB Ch. 3 Art. 30.9; TB Ch. 4 Art. 22.10). These provisions do not apply to gangster offices currently in operation when the provisions of the same paragraph are enforced or applied (TB Ch. 4 Art. 22). The ordinances also allow members of the police to enter the premises if they need to conduct a search, inspect documents, books, and other properties, or question members of the group (TB Ch. 5 Art. 26), and minors cannot enter the premises without a valid reason (TB Ch. 4 Art. 23).

The most visible effect of the application of these regulations was therefore limited to a series of spots around the city: before the Bōtaihō, the yakuza explicitly displayed signs with their names and symbols outside their buildings for the population to see; however, they must now keep their presence concealed. While they are not completely invisible (as cars and people are still showcasing their existence) the official marks that anchored their presence to the territory have vanished. The disappearance from the urban surface of the very name of the group thus wielded a performative effect, as the collective name which granted access to the group’s social capital came to wane. These regulations also had an impact on the operations carried out in the spaces occupied by the yakuza, resulting for example in their expulsion from the night-entertainment industry. In this sense, the displacement of the yakuza went hand in hand with a process of urban cleansing of specific areas, affecting the socio-economic activities that used to take place in those areas and thus creating windows of opportunity for the corporatisation of spaces at the margins of legality. As it will be highlighted later, these processes were underpinned by power dynamics which eventually affected citizens at large, thus displaying the effects of the corporatisation of public spaces. In the next two sections we investigate how they unravelled in two specific areas largely known for their historical yakuza presence, Kabukichō and Nakasu.

Tokyo: Kabukichō

The ward of Kabukichō is internationally renowned for its streets crammed horizontally and vertically with night-time entertainment and red-light venues – a type of activities naturally linked to the yakuza. Indeed, since the end of the war, this area has been a hotbed of criminal activities, mostly operated by the yakuza. While this image of Kabukichō is still crystallised in the popular imagination, just a glimpse to its streets today reveals a completely different scape: stepping into the ward, marked by an imposing, red-coloured arch, one finds oneself walking down a newly paved road that leads towards a ‘life-size’ statue of the head of Godzilla looming over a Toho cinema, rather than its traditional shabby line of shops. Similarly, the number of kyakuhiki (commonly known as kyacchi) – figures luring unaware customers into dodgy bars – has drastically reduced (Kiso 2017). As Miyazaki Manabu nostalgically observes, the typical atmosphere of Kabukichō as it was portrayed in the photographs of Yang Seung-Woo is now gone (interview with Miyazaki 23/04/2020).

The main turning point in the history of the ward occurred in 2002, when the Metropolitan Police Department, alarmed by the high crime rates in Kabukichō, installed fifty security cameras in the area, as well as more illumination for the prevention of crime (NPA 2002, The Japan Times 28/02/2002). This marked the beginning of the cleansing strategy of Kabukichō, which coincided with the beginning of the decline of the yakuza’s presence in the areaFootnote 5 (interview with Miyazaki 23/04/2020). Over the years, the efforts to make streets ‘cleaner’ continued with campaigns targeting kyakuhiki and kyabakuraFootnote 6 scouts trying to hire women for sex-industry related work. Citizen patrol initiatives were also introduced, whereby members of the public could take part in specific courses and become ‘training officers for the prevention of kyakuhiki-like activities’, allowed to patrol the streets alongside the police (Shinjuku-ku 2013). This led to an increased police presence, which seems to have displaced semi-legal activities such as prostitution (allegedly now more concentrated in Shin-Okubo) and escorts. The seemingly successfulness of these ordinances granted the Tokyo Metropolitan Government an excuse to expand the use of CCTVs in other public spaces with numerous bars and sex clubs, such as Ikebukuro (Murakami Wood et al. 2007). The introduction of these sanitising projects naturally affected also activities owned by the yakuza, but their situation worsened with the implementation of the Tokyo Bōhaijorei which introduced limitations to their presence within the ward.

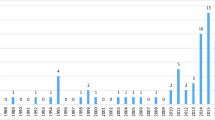

A further sign of the yakuza’s diminished role in these areas has to be found in the decreased collection of mikajimeryō (protection money). Indeed, one of the pillars of the anti-yakuza strategy is the fight against mikajimeryō, which, according to the White Papers of the Police (NPA 2019), remains one of the most significant forms of revenue for the yakuza. As a result of this initiative, both the percentage of yakuza members arrested involved in extortion (from 6.8% in 2009 to 4.6% in 2019) and the total number of yakuza members arrested for extortion (from 1800 in 2009 to 772 in 2019) have decreased (ibid.). The journalist and ex-yakuza member Okita Garyō and Miyazaki both confirm that, although in Kabukichō there are still several shop managers who believe that the mikajimeryō can grant them protection from street thugs, its practice is now diminishing, as it can be reported as extortion and punished accordingly (interview with Miyazaki 23/04/2020, interview with Okita 22/04/2020). Protection money is not paid by shops in major cities anymore, and those shops operated by the yakuza were not able to move to other parts of the city. In addition, a few years later the Bōhaijorei came into effect and the ability of the yakuza of hiring spaces and running businesses was further limited (interview with Okita 22/04/2020).

While the initiatives against Kabukichō’s scouts and toutsFootnote 7 undertaken in the early 2000s by Tokyo Governor Ishihara Shintarō seemed to work at first, in the long run they led to an increasing number of scouts operating in the area, now working in a disorganised fashion to elude law-enforcement (Nippon 03/03/2018). Efforts to maintain the area clean were further strengthened in December 2019 in view of the Tokyo Olympics, when the local government installed speakers that repeated messages against kyakuhiki (Nikkei 07/12/2019). However, rather than having sanctioned a decrease of the levels of criminality, the void left by the yakuza in places like Kabukichō seems to have paved the ground for the emergence of a new type of crime, more loosely and flexibly organised (Nippon 12/12/2017). Commonly referred to as hangure, this crime is now in competition with the yakuza (interview with Okita 24/04/2020). Moreover, while in the past the close ties between yakuza bosses and the police allowed the law enforcement to have a clear awareness of the yakuza’s state of affair and the ability to negotiate, hangure groups, because of their lack of a pyramidal hierarchy and a history of relation with the authorities, represent a hostile force and an obstacle to police investigation given their lack of expertise working with this kind of criminality (ibid.).

Recent events have worsened the situation of the yakuza active in the area: “Now, due to the issue of coronavirus, night-time entertainment and clubs are closed. The yakuza too are practicing jishuku (self-restraint) and staying at home. Before the spread of coronavirus the yakuza were active, even if not as much as in the past. Also the Yamaguchi-gumi infiltrated Tokyo and started their own business, but after their split their activities have decreased again. In Shinjuku, the Kōhei Ikka of the Sumiyoshi-kai is the one with the most influence.” (interview with yakuza boss 21/04/2020).

The ongoing superficial hygienisation of Kabukichō aimed at matching with the image of a safe (and thus commodifiable) area thus hides a struggle for power: the increasing weakness of the yakuza is not only leaving vacant their physical spaces, but also their role as regulators of the underworld in one of their historical strongholds.

Fukuoka: Nakasu

The ward of Nakasu, in the prefecture of Fukuoka, Kyūshū, is another place renowned for its long history of yakuza presence. While the region of Kyūshū is relatively small, it is home to a conspicuous number of yakuza groups, such as the Kudō-kai, the Dōjin-kai and the Taishū-kai, among many others. Unlike the Tokyo metropolitan area, where the flux of transnational capital and tourism have called for a great investment in the containment of the yakuza, the Kyūshū region remains geographically as well as economically far from the centre of the country. Nonetheless, being the main city in Kyūshū, Fukuoka is socially and economically active and thus offers a night-time entertainment district proportionally comparable to that of Kabukichō. The high concentration of yakuza groups in the area prompted the local government to introduce the first Bōhaijorei in Japan, which paved the way for similar ordinances throughout the country.

As of today, thirty police officers are deployed in the area to patrol the main streets of Nakasu. In addition to this, there is a special investigative team, composed of twenty police officers in plainclothes, who specifically police crimes involving adult entertainment and illegal casinos (interview with Yabu 21/08/2020). In 2009, the police of Hakata city (Fukuoka) had already launched the ‘Hakata Marubo Zero Sakusen’ (Strategy zero yakuza in Hakata), which was revised in 2016 to implement a strategic focus on the adult entertainment district of Nakasu. This strategy was based on four pillars: the exclusion of kyaku-hiki and bōryokudan, an increased control of ‘bad’ shops, a cutting-off of yakuza revenues, and a clean-up of the district (Fukuoka Keisatsusho 2019). Specifically, the Fukuoka prefectural police enforced five bans: 1) Yakuza members cannot access shops exposing the ‘bōryokudan’in tachiiri kinshi’Footnote 8 sticker; 2) It is forbidden to expose one’s membership to a certain yakuza group in order to receive favours or intimidate; 3) It is forbidden to request protection money; 4) It is forbidden to request money through physical intimidation; 5) It is forbidden to request donations and hush money (Hakata Keisatsusho 2019). As reported by Yabu (interview with Yabu 21/08/2020), since the implementation of this strategy police officers have been entering different stores simultaneously to question the owners and collect information on the activities of the yakuza. However, this strategy has achieved little, as owners and operators often refuse to provide useful information to the police – in particular since the Dōjin-kai took over this area, which was traditionally controlled by the Fukuhaku-kai.

Although local newspapers reported that gangsters’ cars have disappeared from the streets and the number of yakuza headquarters has also declined, information offices that advertise the flourishing sex industry of Nakata have increased, and many of these have been reported to be related to the yakuza. Totani Kōichi, the chief of police, confirmed that the activities of the yakuza have in fact become more difficult to detect (Nishinippon Shinbun 24/04/2019a). This seems of be one result of the processes of hygienisation of the streets of Nakasu: the sex industry changed from visible brothels advertised through pictures hanging outside the premises and a network of touts, to a net of discreet information centres advertising call girls through magazines and websitesFootnote 9 (interview with Yabu 21/08/2020).

While in Kyūshū the yakuza are not as weakened as in other parts of the country, the decreased collection of mikajimeryō seems to confirm a shrinkage of the yakuza business, which is also related to an increase in the sphere of influence of hangure groups (interview with Miyazaki 24/04/2020). Hirosue Noboru (interview with Hirosue 10/04/2020), a Fukuoka-based yakuza researcher, also confirms this trend, noting how “the presence of the yakuza in Nakasu is becoming more invisible, and the number of shops paying mikajimeryō is decreasing after the Bōhajorei”. According to him, the yakuza are now relying on hangure or members who pretend to have left the group as a strategy of organisational preservation: even in the case of arrest, their ties with the boss cannot be proven. At the same time, police intervention in Fukuoka is less aggressive, and often the police merely advise that shop owners use the ‘bōhai hyōshō’ (an anti-yakuza sticker) on the door to prevent people related to the yakuza from entering the premises.

Thus, in Nakasu too, urban spaces traditionally owned and used by local yakuza gangs have been increasingly removed to pander to the discourse endorsed by the state rhetoric on security. For instance, in December 2019 the Fukuoka prefectural police seized the headquarters of the yakuza group Taishū-kai, which was located in a building in the city of Tagawa (Nishinippon 21/01/2020). More significantly, the headquarters of the powerful Kudō-kai were removed from the city centre in the same period. While this decision was taken within the police initiatives ‘Strategy to destroy the Kudō-kai’, the plan went through only after the group agreed to move their offices in a less central part of the town (Nishinippon 27/09/2019b).

As for the night-time entertainment, Hirosue reports that the majority of people involved in the sector confess a preference for the protection services offered by the yakuza since they are able to resolve disputes swiftly, contrarily to the police which usually require an early closure of the shop to deal with troublemakers (interview with Hirosue 10/04/2020). This fact is corroborated by Yabu, who maintains that the relationships between the operators of the adult entertainment sector and the local yakuza are long-standing and deeply rooted (interview with Yabu 21/08/2020). Nevertheless, the reduced presence of the yakuza is opening a power vacuum in the night-time entertainment sector, still in need of extra-legal protection. This vacuum is being exploited by non-traditional forms of crime such as hangure and Chinese-led gangs, which are less prone to a strict observance of the newly enforced anti-crime ordinances. In fact, as Hirosue observes, after the Bōhaijorei the amount of Chinese-owned shops increased, and as a result the number of young men working in the streets as kyacchi increased accordingly, replacing those who were in the same line of work but in connection to the yakuza (interview with Hirosue 10/04/2020).

The spatial displacement of the yakuza in Nakasu did not reach the same level as that of Kabukichō. Their resilience is connected to two main factors: firstly, they still enjoy social acceptance amongst the population, and in particular night-time entertainment operators, as they are still seen as having enough power to act as dispute resolutors. Secondly, the concentration of corporate capital in the relatively peripheral area of Kyūshū is not as high as in Tokyo, and as such the hygienisation of the urbanscape has not been implemented as drastically as in Kabukichō. Nevertheless, the increasing number of criminal groups alternative to the yakuza shows how Nakasu is not immune to the dynamics at work in the capital, but it is just lagging behind.

Conclusion

As the cases of Kabukichō and Nakasu demonstrate, in conjunction with the increasing neoliberal stance of the state and its impact over urban spaces, the yakuza’s visibility, as well as their influence over society, have been diminishing. This needs to be considered as a result of several factors which have contributed to a general state of crisis of the yakuza, such as thirty years of economic stagnation, an increased state surveillance in concomitance with politics of hygienisation aimed at showcasing the Japanese image for international scrutiny, and an increasingly negative attitude towards the yakuza within Japanese society.

Although the yakuza have initially been able to exploit the chances of capital accumulation offered by the neoliberal policies of deregulation and financialisation of the economy – which temporarily allowed them to make more visible their presence in the city – the anti-yakuza policies eventually impacted the symbols of power of the yakuza in the urbanscape. However, it is not the powerful bosses such as Tsukasa Shinobu, leader of the Yamaguchi-gumi, who have disappeared from the public sphere, but the socially undesirable, low-ranking members, who have been particularly struggling because of the increasing social inequality and the impossibility of being reintegrated into civil society (Baradel 2019). The current invisibility of the yakuza is thus contributing to highlight some of the most socially deleterious dynamics of contemporary politics in Japan. Indeed, the current condition of places such as Kabukichō and Nakasu is a clear marker of the socially disruptive and criminogenic effects of the neoliberal trajectory, whereby a state-sanctioned crackdown on official criminality is not counterbalanced by effective social policies for the containment of its socio-economic effects. Indeed, as data have shown, such crackdown did not result in an actual reduction of criminal activity per se, but quite the contrary: without the development of welfare policies and anti-corruption regulation in the financial sector, the physical displacement of the yakuza merely smoothened a ‘sanitisation’ of the city’s outlook. This rendered spaces such as Kabukichō appealing targets of private investments, while cloaking the presence of increasingly precarious social strata under the veil of luxury brands and chain retailers.

According to the same logic, the need to promote highly-commodified, ‘anshin-anzen’ (safe-secure) urban environments also underpinned a process of expulsion of all elements of visual disturbance, encompassing not only the yakuza but other marginalised social actors such as homeless people. This occurred, for example, through implementation of urban impediments such as strong lights and single-seat benches in parks where the homeless usually sleep. Subjects regarded as economically irrelevant such as low-ranking yakuza and Tokyo clochards are not considered worth reintegrating into civil society: they simply ought to vanish (Baradel 2020). At the same time, such an extension of punishment across social strata runs in parallel with an extension of prohibitions to encompass an increasing series of everyday activities across the city. In this regard, it is indicative to note how it is now forbidden to access most areas of central Tokyo with a bicycle, and how such prohibition has been semiotically naturalised through an overload of prohibition signs scattered around the city stations.

As the current analysis suggests, the combination of a weakened yakuza and a systematic lack of social outlets for the poor seems to be resulting in the rise of more disorganised and less predictable forms of street crime. Hangure and Chinese-led gangs, traditionally concealed by the pervasive presence of the yakuza, are now coming to the fore in the underworld, and in those particular urban spaces where semi-legal and illegal activities are condensed. Further research is therefore necessary: analysis similar to that conducted in the areas of Kabukichō and Nakasu could be carried out in areas with intense concentration of yakuza’s activities, novel forms of crime could be kept monitored in order to understand the possible presence of discernible patterns in their activity, and special attention should be put on the mechanisms of extra-legal governance in light the transforming dynamics spurred by the Covid-19 crisis and the postponement of the Tokyo Olympics. At the time of writing, one can only speculate on which new forms of governance will come to replace the former yakuza monopoly.

Notes

The yakuza (Japanese criminal syndicates) are also referred to as bōryokudan, meaning ‘violent groups’, a term often employed by the media but antagonised by the yakuza themselves. The main yakuza groups are the Yamaguchi-gumi, the Sumiyoshi-kai, and the Inagawa-kai.

As defined by Letizia Paoli (2003: 63).

Hangure is the common name used to describe non-yakuza criminal groups and networks which are not organised in a hierarchical, permanent structure like the yakuza; Chinese-led gangs are criminal networks composed of Chinese residents in Japan. Neither of them is recognised and registered by the Public Safety Commission.

From the Bōtaihō until the Bōhaijōrei, policymakers continued legislating on yakuza groups and activities through amendments to the Bōtaihō and laws concerning the yakuza (Mayaku Tokurei-hō [Anti-Drug Provisions Law], 1991; Soshiki Hanzai Shobatsu-hō [Organised Crime Punishment Law], 1999; Hanzai Shūeki Iten Bōshi-hō [Transfer of Criminal Proceeds Prevention Law], 2007). However, these exceed the scope and interest of the present article given its focus on yakuza’s visibility.

Similar provisions were implemented in 25 other areas of Tokyo (see Keisatsuchō 2016).

Hostess clubs.

The notorious case of the ‘Zama Killer’, in which a scout killed and dismembered six hostesses and three high-school students, shed light on the underworld of Kabukichō scouts (Nippon 2018).

‘Entrance prohibited to bōryokudan members’.

For instance, in 2011 the price for a page of adult entertainment information magazine managed by the Kudō-kai affiliated Tanaka-gumi started from ¥50,000 (£360), the same price applied to online advertisement for escort services. In 2012, ‘W’ company, suspected of having close ties to the yakuza, registered annual sales of ¥6.5 billion (£43 million). The company has since changed the name, and last year registered sales for ¥14 billion (£100 million).

References

Baradel M (2019) The rise of shaming paternalism in Japan: recent tendencies within the Japanese criminal justice system. Trends in Organized Crime, 1-19

Baradel M (2020 forthcoming) The yakuza on trial: sentencing patterns of members of Japanese organised crime. J Japanese Law, 25/49

Bōtaihō – Bōryokudan-in ni yoru futōna kōi no bōshi-nado ni kansuru hōritsu [Law for the prevention of improper conduct by members of the bōryokudan] (1991) Law nr 77. Retrieved from: http://elaws.e-gov.go.jp/search/elawsSearch/elaws_search/lsg0500/detail?lawId=403AC0000000077_20171201_429AC0000000046&openerCode=1 [Last access 15/05/2019]

Bourdieu P (1986) The forms of capital. In: Richardson J (ed) Handbook of theory and research for the sociology of education. Westport, Greenwood, pp 241–258

Campana P (2011) Eavesdropping on the mob: the functional diversification of mafia activities across territories. Eur J Criminol 8(3):213–228

Catino M (2019) Mafia organizations: the visible hand of invisible enterprise. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Cybriwsky R (1999) Changing patterns of urban public space. Cities 16(4):223–231

Deleuze G (1992) Postscript on the societies of control. October 59: 3–7

Diaz-Cayeros A, Magaloni B, Matanok A, Romero V (2011) Living in fear: mapping the social embeddedness of drug gangs and violence in Mexico. Manuscript: University of California at San Diego 90:91–98

Dower JW (1999) Embracing defeat: Japan in the wake of world war II. W.W. Norton & Co., New York

Foucault M (1995) Discipline and punish: the birth of the prison. Random House, New York

Fukuoka Keisatsusho (2019) Hakata marubō zero sakusen [Strategy zero yakuza in Hakata] Availble at: https://www.police.pref.fukuoka.jp/fukuoka/hakata-ps/hakatamarubouzerosakusen/hp-marubouTOPpage-h290222.html [Last access 25/04/2020]

Fukuoka-ken Bōryokudan Haijojōrei (2010) Fukuoka-ken Jōrei Dai-59go, 19 October. Available at: http://www.city.nakama.lg.jp/kurashi/bosai/bouryokutuihou/index/documents/bouhaijourei.pdf [Last access 25/04/2020]

Gambetta D (1993) The Sicilian mafia. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Gambetta D (2009) Codes of the underworld. How criminals communicate. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Hakata Keisatsusho (2019) Bōryokudanhen [Bōryokudan issue] [online] Available at: https://www.police.pref.fukuoka.jp/fukuoka/hakata-ps/hakatamarubouzerosakusen/hp-bouryokudan.html?fbclid=IwAR0GUEf3gsarGiSdPI6plttPizVu7RYu62TZ_jWpGpJXZC-ARuMJfFSjobY [Last access 27/07/2020]

Hill P (2003) The Japanese mafia: yakuza, law, and the state. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Ino K (1999) Yakuza to nihonjin [Yakuza and the Japanese]. Tokyo, Chikuma

Kaplan D, Dubro A (2003) Yakuza: Japan’s criminal underworld. University of California Press, Berkeley

Keisatsuchō (2016) Meiwaku bōshi jōrei [Anti-disturbance ordinances] [Online] Available at: https://www.keishicho.metro.tokyo.jp/smph/about_mpd/keiyaku_horei_kohyo/horei_jorei/kyaku_ku.html?fbclid=IwAR2nAsU_bJHyzbPPTPnOQdLf1OYwl_zxqjPalSHdN494wfecDPy8vWOdRYY [Last access 25/04/2020]

Kiso T (2017) Kyakuhiki kinshi jōrei [Anti-scounting ordinances] Yahoo News, 3 October [online] available at: https://news.yahoo.co.jp/byline/takashikiso/20171003-00076492/ [Last access 15/04/2020]

Messner SF, Rosenfeld R (2000) Market dominance, crime and globalization. In: Karstedt S, Bussman K (eds) Social dynamics of crime and control: new theories for a world n transition. Hart Publishing, Oxford, pp 13–26

Milhaupt CJ, West MD (2000) The dark side of private ordering: an institutional and empirical analysis of organized crime. U Chicago Law Rev 67:41

Miyazaki M (2008) Yakuza to Nihon [Yakuza and Japan]. Tokyo, Chikuma

Miyazaki M (2010) Kindai yakuza kōteiron [Positive theory of modern yakuza]. Tokyo, Chikuma

Mizoguchi A (2011) Bōryokudan. Tokyo, Shinchōsha

Mizushima K (1986) Nihon no shakai byōri genshō [Social pathological phenomena in Japan] Seikatsu rigaku kenkyū, 8: 1-16

Murakami Wood, Lyon, Abe (2007) Surveillance in urban Japan: a critical introduction. Urban Stud 44(3):551–568

Nikkei (Nihon Keizai Shinbun) (2019) Eizō minagara kyakuhiki chūi: Kabukichō, keishichō ga shintaisaku [Careful about kyakuhiki when you walk watchin a video: the new strategy of Kabukichō and the police] [online] 07/12/2019. Available at: https://www.nikkei.com/article/DGXMZO53076620X01C19A2CE0000/ [Last access 26/04/2020]

Nippon (2017) The upstart gangs filling the yakuza power vacuum. Nippon, 12 December [Online] Available at: https://www.nippon.com/en/features/c04205/?fbclid=IwAR1pOTMYIYTLPbReXG6MnWNd1cze1xNfDOULEULMs4sNKiWeKBoEfe7Wdis [Last access 19/03/2020]

Nippon (2018) Scouting for the sex industry: the Kabukichō background of the Zama Killer. Nippon, 8 March [Online] Available at: https://www.nippon.com/en/features/c04207/scouting-for-the-sex-industry-the-kabukicho-background-of-the-zama-killer.html?pnum=1 [Last access 21/03/2020]

Nishinippon Shinbun (2019a) Botsui ni jū nen nakasu ni henka [After 10 years of anti-yakuza regulations a change in Nakasu] 24 April. Available at https://www.nishinippon.co.jp/item/n/505320/?fbclid=IwAR025DATIq2IuaqvMn7-dwMTYgG7pF2VvuFpYRVOvTUPbbK8diaOIMjykWs [Last access 15/03/2020]

Nishinippon Shinbun (2019b) Kudōkai no honmaru rakujō [The surrender of Kudōkai’s inner citadel] 27 September. Available at: https://www.nishinippon.co.jp/item/n/546481/ [Last access 05/04/2020]

Nishinippon Shinbun (2020) Taishūkai jimusho wo manshon kara tekkyo [Removal of Taishū-kai office from building] 21 January. Available at: https://www.nishinippon.co.jp/item/n/577376/ [Last access 23/03/2020]

NPA (National Police Agency) (2002) Chiiki no anzen wo mamoru shokatsudō [Activities to protect the safety of the region] [online] Available at: https://www.npa.go.jp/hakusyo/h14/h140301.html [Last access 26/04/2020]

NPA (National Police Agency) (2019) Meirei Motonen-han Keisatsu Hakusho [White Paper of the Police of Reiwa 1] [online] Available at: https://www.npa.go.jp/hakusyo/r01/index.html [Last access 22/04/2020]

Paoli L (2002) The paradoxes of organized crime. Crime Law Soc Chang 37:51–97

Paoli L (2003) Mafia brotherhoods. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Passas N (1999) Globalization, criminogenic asymmetries, and economic crime. Eur J Law Reform 1(14):399–423

Passas N (2000) Global anomie, dysnomie, and economic crime: hidden consequences of neoliberalism and globalization in Russia and around the world. Soc Justice 27/2(80):16–44

Rankin A (2011) 21st century yakuza: recent trends in organized crime in Japan. Asia Pacific J 11(7):1–27

Reiner R (2007) Neoliberalism, crime and justice. In: Roberts R, McMahon W (eds) Social justice and criminal justice. Centre for Crime and Justice Studies, London, pp 8–21

Sciarrone R, Storti L (2014) The territorial expansion of mafia-type organized crime. The case of the Italian mafia in Germany. Crime Law Soc Chang 61(1):37–60

Sergi A (2015) Mafia and politics as concurrent governance actors. Revisiting political power and crime in southern Italy. In: Van Duyne PC, Maljević A, Antonopoulos GA, Harvey J, Von Lampe K (eds) The relativity of wrongdoing: corruption, organised crime, fraud and money laundering in perspective. Wolf Legal Publishers, Oisterwijk, pp 43–70

Sergi A (2017) From mafia to organised crime: a comparative analysis of policing models. Palgrave MacMillan, Cham

Shinjuku-ku [City of Shinjuku] (2013) Kōhō Shinjuku dai 2077 go [Shinjuku public bullettin number 2077] Available at: http://www.city.shinjuku.lg.jp/content/000130821.PDF?fbclid=IwAR26voDU3V7wR1Ott5JSuItl99cHBXTL7og54dS5ILYKTqBQrlmHYAOJe_0 [Last access 26/04/2020]

Shushōkantei [Prime Minister of Japan and his cabinet] (2016s) Dai hyakuhachijusankai kokkai ni okeru Abe Naikaku Sōridaijin shiseihōshin enzetsu [Prime Minister Abe’s policy speech at the 183rd Diet] Available at: https://www.kantei.go.jp/jp/96_abe/statement2/20130228siseuhousin.html [Last access 25/04/2020]

Skaperdas S (2001) The political economy of organized crime: providing protection when the state does not. Econ Gov 2(3):173–202

The Japan Times (2002) Kabukichō gets 50 anti-crime cameras. The Japan Times, 28 February [Online] Available at: https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2002/02/28/national/kabukicho-gets-50-anticrime-cameras/?fbclid=IwAR3q21Bu0g5tp3rPkyczz1EfGJOXt_0WD6hafUfUT5bR26OvAmIufhXZuJ8#.XqRwOlMzab- [Last access 21/04/2020]

Tōkyō-to Bōryokudan Haijojōrei (2011) Tōkyōto Jōrei Dai 54-go, 18 March. Available at: https://www.keishicho.metro.tokyo.jp/kurashi/anzen/tsuiho/haijo_seitei/haijo_jourei.files/jourei.pdf [Last access 25/04/2020]

Varese F (2011) Mafias on the move: how organized crime conquers new territories. Princeton, Princeton University Press

Wacquant L (2009) Punishing the poor: the neoliberal government of social insecurity. Duke University Press, Durham and London

Yoshimi S (2003) ‘America’ as desire and violence: americanization in postwar Japan and Asia during the cold war. Inter-Asia Cult Stud 4(3):433–450

Zhang S, Chin K-L (2002) Enter the dragon: inside chinese human smuggling organizations*. Criminology 40:737–768

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Informed consent

Informed consent was ensured through adherence to the British Society of Criminology guidelines on Ethical Practice, and it was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix: Interviews

Appendix: Interviews

Hirosue Noboru, 10/04/2020

Miyazaki Manabu, 23/04/2020

Okita Garyō, 24/04/2020

Yabu Masataka, 21/08/2020

Yakuza boss, 21/04/2020

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Baradel, M., Bortolussi, J. Under a setting sun: the spatial displacement of the yakuza and their longing for visibility. Trends Organ Crim 24, 209–226 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12117-020-09398-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12117-020-09398-4