Abstract

EU consumer policy is a policy area that is receiving increased attention and is considered important for the proper functioning of the internal market. Yet, as with many other supranational policy areas, conflicting positions of the Member States have led to many compromises and rejections of EU-initiated proposals. By building on regime theory and previous research identifying consumer policy regimes, the aim with this article is to investigate potential patterns in countries’ preferences in EU consumer policy. With this, the article seeks both to contribute to the theoretical understanding of factors influencing Member States’ positions to EU consumer policy and to the debate on how future EU consumer policies should be designed and put into power. Differences in country and regime preferences are analysed using data collected through an open public consultation as part of the European Commission’s Fitness Check of European consumer and marketing law in 2016 and through interviews with key stakeholders in 2018. The results show that there are substantial differences between the regimes and that the level of harmonization of consumer and marketing law seems to be the most contested issue. Furthermore, the article points to several potential reasons for these differences between countries and regimes and recommends that future studies should be undertaken to generate deeper knowledge about the effects of these explanatory factors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Since consumer policy was established as a separate policy field of the European Communities, when the Council of Ministers endorsed the five basic “rights” of consumers in 1972, the policy field has received increased attention and has grown in importance. Today, it is perceived as a central policy field of the European Union (EU) due to its importance for the creation and functioning of the internal market. The aims of the supranational policy are both to assure a high level of consumer protection in the Union and to reduce differences between the consumer law and regulations of the various Member States in order to achieve a proper functioning of the internal market (European Commission 2012). This has also been a key result of EU consumer policy as national consumer policies and regulations have converged. However, both at EU and national levels, consumer policy is rooted in numerous policy technicalities and market arrangements, and as with other supranational policy fields, interest differences and conflicting positions of the Member States have led to many compromises and rejections of EU-initiated proposals (e.g., Howarth and Sadeh 2010; Pollack 1997).Footnote 1

In order to enable policy measures that promote desirable outcomes, it is essential to better understand the context in which EU decision making in the field of consumer policy takes place. To achieve this, it is important to understand the differences between countries and key stakeholders at the national level with regard to their preferences in EU consumer policy.

The formation of national preferences and negotiating positions, both in negotiations on EU policy and in general, have been comprehensively studied and theorized within the field of international relations, and a multitude of potential influencing factors have been pointed to (e.g., Bailer 2011; Elgström et al. 2001; Keohane and Nye 2012; Moravcsik 1997; Putnam 1988). More specifically, studies investigating decision-making in the EU in general have identified some key dimensions distinguishing country preferences. These are a geographical, mainly north-south, dimension (Elgström et al. 2001; Kaeding and Selck 2005; Mattila and Lane 2001; Thomson et al. 2004; Zimmer et al. 2005), a preference for regulatory versus market-based solution dimension (Thomson et al. 2004), and a redistributive dimension (Zimmer et al. 2005). Nevertheless, few studies have been undertaken on Member States’ preferences and positions in EU consumer policy. The main approach to this topic has been to compare the policies of individual countries with the policies of the EU (e.g., Weatherill 2013). This has also been the approach taken in the European Commission’s own studies of consumer problems and markets and in the European Commission’s country reports. Due to the high amount of countries and policy issues, this approach results in complex analyses and difficulties in identifying patterns in country preferences.

The comparative studies of consumer policy in Europe have been dominated by studies taking a regime approach in seeking to identify similarities and differences in consumer policy between groups of countries. Despite different objectives and scientific perspectives, these studies have identified various European consumer policy regimes that to varying extents incorporate the key variables identified in international relation studies on the formation of states’ preferences and positions in negotiations. The regimes are classified based on differences in how consumer interest have been institutionalized (Trumbull 2006a, 2006b, 2012), on differences in legal tradition or enforcement tradition (Cseres 2005; Cafaggi and Micklitz 2009; Micklitz 2003), or a combination of these (Nessel 2019; Repo and Timonen 2017). Given that the consumer policy regimes incorporate key variables often found to determine countries’ preferences in international negotiations, and the claimed continuity of regimes, it can be hypothesized that it is possible to identify differences between the consumer policy regimes when it comes to preferences in EU consumer policy. However, recent research argues that, perhaps due to the efforts by the European Commission to harmonize EU consumer policy, the regime approach is of little value for understanding differences in European consumer policy today (Nessel 2019; Strünck 2005).

Therefore, by adopting the regime approach, the aim with this article is to investigate whether, and potentially why, there are regime differences when it comes to country preferences in EU consumer policy. Compared with the previous efforts to study preferences in EU consumer policy, the regime approach enables a more systematic analysis of which the results may be used to better understand how various policy aims, initiatives, and measures may be received in the various Member States.

This article first elaborates the idea of consumer policy regimes, and based on previous research, six regimes are theoretically deduced for further analyses. The potential differences between these regimes in their preferences regarding key elements of EU consumer policy are investigated through analysis of results from an open public consultation organized by the European Commission in 2016 and through analysis of interviews with key stakeholders in 2018. The results are discussed focussing on key differences between the regimes, reasons for differences, and the potential usefulness of this regime classification for the future understanding as well as shaping of EU consumer policy. Finally, the article concludes with recommendations for future research.

Consumer Policy Regimes

National strategies for consumer protection as well as the development of consumer markets are often seen as a result of institutional and historical characteristics. According to Reich (in McGregor 2017, p. 685), consumer policies are “embedded in social institutional arrangements that heavily influence their organization, their goals and strategies, as well as their efficiency and effectiveness.” Due to the varying traditions and history of national consumer policies, it is therefore reasonable to expect that national approaches to consumer policy vary significantly across Europe and that this may influence these countries’ positions to EU consumer policy. However, in addition to studying individual country approaches to consumer policy, it can be valuable to study similarities and differences in countries’ approaches to consumer policy since consumer policies seldom have developed isolated from the political processes in other, especially neighbouring, countries. Studying similarities and differences is also seen as a way of identifying key variables and mechanisms influencing certain outcomes and as means for formulating successful policy measures for different types of challenges and settings (Repo and Timonen 2017). In this article, national preferences in EU consumer policy are therefore studied through the regime approach.

The Regime Approach

The regime approach assumes that regimes are established, formally or informally, as a result of legal and institutional features being systematically interwoven in the relation between state and economy (Esping-Andersen 1990, p. 2). The positions on how regimes should be defined and understood are manifold, depending on the researchers’ ontological perspective. However, although several efforts have been made to clarify, modify, or even supplant the so-called consensus definition of the term “international regime,” this is still one of the most commonly used definitions (Hasenclever et al. 1997, p. 8). According to Krasner (1982, p. 186), regimes can be defined as “sets of implicit or explicit principles, norms and decision-making procedures around which actors’ expectations converge in a given area of international relations.” On the same note, May and Jochim (2013, p. 428) conceptualize policy regimes as the “governing arrangements for addressing policy problems,” and these governing arrangements can be “broadly construed to include institutional arrangements, interest alignments, and shared ideas.” Esping-Andersen (in Wilson 2000, pp. 256–257) furthermore argues that policy regimes can be defined in “terms of power blocs, ideology and institutional arrangements.” Regimes can thus be seen as groups of countries with similarities along these lines, and according to Repo and Timonen (2017, p. 126), consumer policy regimes indeed draw attention to similarities and differences between groups of countries and cover the principles, norms, rules, and institutions of consumer policy.

The existing classifications of European consumer policy regimes, as presented in the next section, were developed based on the political situation in selected (mostly Western) European countries in the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s. Since then, much has changed in European consumer policy as national consumer policy to a certain extent has given way to EU policies and since more countries have joined the EU. Trumbull (2006b, p. 82) acknowledges that new political forces, such as directives from Brussels, have placed pressures on established national models, but argue that coherent national institutions that reflect and support distinctive narratives about the role of the consumers can still be identified. This is consistent with the regime approach that assumes that regimes do evolve, but that this happens slowly as they are embedded in the existing institutional structures that channel and structure their behaviour (Pierson 2000). It is therefore reasonable to expect that, except for the addition of countries, the changes to the regime classifications have not changed substantially. According to Krasner (1982), regime changes require substantial changes in policy paradigms and shifts in political powers and organizational arrangements. The regime consistency is explained by path dependence theory, which is based on the premise that organizations and actors are part of institutions that channel and structure their behaviour along more or less established paths. When they reform institutions, actors do not only follow their functional needs, but they are also influenced by the prior and existing institutional settings (Krapohl 2007). According to Pierson (2000), once an institution is established, it might pay of more and more to stick to that institutional arrangement because of the so-called “increasing returns.” Four factors lead to such increasing returns. New institutions are costly to create and often generate learning effects, coordination effects, and adaptive expectations. Institutions and policies may lead actors’ to invest in specialized skills, deepen relationships with other individuals and organizations, and develop particular political and social identities (Pierson 2000, p. 259). Furthermore, institutions and policies may lead to specific forms of governing and may contribute to the establishment of new organizations and other governing tools. These activities increase the attractiveness of the existing institutional arrangements.

Classifications of Consumer Policy Regimes

Studies undertaken on national consumer policies and the sources of national diversity take into account the organization of producers and consumers, the roles of government and their regulation of markets, the countries’ legal and enforcement traditions as well as the activities of interest groups. To varying extents, these factors have been used to identify consumer policy regimes distinguishing countries in terms of power blocs, ideology, and institutional arrangements. In the literature on consumer policy regimes, the works of Trumbull (2006a, 2006b, 2012), Micklitz (2003), and Cseres (2005) stand out as particularly important. Another classification of countries that has been influential is the distinction made by the European Commission as it has been used in several of their market studies (e.g., European Commission 2014). This classification emphasizes the spatial variation in the approaches to consumer policy within the EU.

Trumbull (2006a, 2012) argues that national consumer policy models came as a result of how the governments in their regulatory efforts were dictated by a struggle between the organized interests of producers and consumers. He distinguishes between three ideal type policy models for consumer policy based on how variations in regulatory coalitions influenced the regulatory approach. In countries classified within the negotiation model, of which Scandinavian countries are used as example countries, industry associations and individual companies negotiated directly with consumer associations to set important areas of consumer policy. Countries classified within the negotiation model tend to favour regulatory approaches that encourage mediation and assume that consumers and producers can come to agreement on satisfactory regulatory approaches to consumer protection. Countries classified within the protection model, of which France is used as an example country, relied on a state-activist coalition that resulted in an emphasis of the role of the government in insulating consumers from market externalities and the role of consumers and interest groups in lobbying for new rights and protection. This approach to consumer protection led to strong legal and regulatory protections for consumers and regulations that placed the overwhelming burden of consumer safety on producers. In countries classified within the third model, the information model, of which Austria and Germany are used as example countries, the industry and the state were the primary actors in the shaping of consumer policy. This model stresses the challenges of market failure and the importance of remedying information asymmetries working to the disadvantage of consumers. Compared with countries belonging to the other regimes, countries belonging to the information regime tend to be more in favour of product labelling, accurate advertising, quality standards, contractual clarity, and consumer education coupled with relatively weak legal protections.

Micklitz (2003), on the other hand, distinguishes between four types of consumer policy regimes, mainly based on the differences in legal traditions. He argues that four consumer policy regimes can be identified: the common law area, the Romance area, the Germanic, and the Scandinavian area. Consumer policy in Common law countries, being politically pragmatic, is constrained to precise regulations by strictly limiting the capacity to act as well as self-regulation. Law enforcement is restricted to the state authority and cooperative structures are sparsely developed. Consumer policy in Romance countries, with their tradition of policy centralism, is characterized by an interplay between free markets (laissez-faire) and interventionism. Semi-state consumer associations hold a legitimating supportive function. Consumer policy in Germanic countries, which is based on a tradition of coherence within the legal system, is characterized by enforcement through safeguarding through courts and by co-operative structures in which consumer associations play a significant role. Finally, consumer policy in Scandinavian countries is characterized by co-operation between public and private actors. Regulatory interventions vary between privatization and nationalization, and when it comes to law enforcement, centrally organized state authorities, such a ombudsmen, are predominantly solving problems by cooperation (Micklitz 2003, pp. 1046–1047).

A similar distinction is made by Cseres (2005), who also classifies the consumer policy approach of countries based on legal tradition. She distinguishes between Germanic-, Nordic-, Common law-, and Franco-Roman countries. In addition, and contrary to the other classifications, Cseres (2005, pp. 166–170) also distinguishes Eastern European countries, formerly planned economies, as a separate group of countries. Consumer law in these countries was first enacted in the second half of the 1990s, and the EU accession process, which involved an obligation to bring their laws closer to EU law, greatly stimulated the creation of an independent and autonomous area of consumer protection. Cafaggi and Micklitz (2009) also widened Micklitz’ initial classification by adding an Eastern European regime of consumer law enforcement.

These classifications are based on different criteria, and each of the classifications only factors in a limited number of variables into the country groupings. Furthermore, neither of the classifications are exhaustive to the extent that they classify all EU and European Economic Area (EEA) countries according to regime type. Nevertheless, although they are based on different criteria and are not fully aligned, there are many similarities between the classifications. The above-mentioned classifications, as well as established country categorizations provided by the European Commission (e.g., European Commission 2014), are therefore used as a starting point for making a complete categorization of EU and EEA countries according to consumer policy regimes. Based on these previous classifications, the review of regime approaches to studies of consumer policy by Nessel (2019) and the classifications made by Repo and Timonen (2017) when analysing regime market performance, this article distinguishes six consumer policy regimes. This classification is used as a starting point for investigating similarities and differences, i.e., potentially shared ideas, between countries in their position to key issues in EU consumer policy.

The Nordic regime is evident in all classifications and consists of Finland and Iceland in addition to the Scandinavian countries. A Southern European regime is also fairly clear based on the European Commission classification and partly on Micklitz’ classification of Romance countries. Eastern European countries also form a regime of its own based on their recent enactment of consumer law and policy and the similar influence on the development of consumer law and policy by the EU as part of the accession process (Cafaggi and Micklitz 2009; Cseres 2005). The categorization of countries is not equally clear when it comes to the core countries of the EU.Footnote 2 Both Trumbull and Micklitz distinguish a Germanic regime, which in this article consists of Germany and Austria. They are, however, less clear on how to treat the United Kingdom (UK). When talking about the protection model, Trumbull (2006a, 2012) groups the UK together with France and the United States, but when talking about types of citizenship, Trumbull (2006b) argues that the UK interpreted consumerism as economic citizenship and groups the UK together with Germany, Austria, and Japan. Micklitz (2003) considers the UK as part of a group of common law countries. As Trumbull does not consider other Commonwealth of Nations countries, UK is categorized in this article as part of an Anglo regime together with Malta, Cyprus, and Ireland due to the institutional heritage of the Commonwealth of Nations and British-influenced administration (similar to Repo and Timonen (2017)). Finally, a Franco-Roman regime, consisting of France, the Netherlands, Belgium, and Luxembourg, is distinguished based on their common legal traditions and close proximity (Cseres 2005). Table 1 depicts the suggested regimes and the countries categorized in them for this analysis.

This regime classification seeks to combine what Nessel (2019) terms the “legal” and the “political science” perspective on consumer policy. Furthermore, the classification do, to a certain extent, cover the previously mentioned key dimensions distinguishing country preferences in EU decision-making, such as the geographical and the regulatory versus market-based dimension. Nevertheless, there are many limitations connected with the existing classifications and it has been argued that the legal and political science perspective only contribute to explain some differences between consumer policies in individual countries (Nessel 2019). On this background, this research also takes an exploratory approach to the investigation of potential regime differences and potential reasons for such differences, in preferences in EU consumer policy through the stakeholder interviews.

Data and Methodology

The potential existence of regime differences in countries’ preferences in EU consumer policy is examined through analysis of data collected through an open public consultation that was part of the Fitness Check of EU consumer and marketing law, and through analysis of data collected through semi-structured interviews and a survey based on similar questions with key national stakeholders.

Open Public Consultation

The Fitness Check of EU consumer and marketing law was conducted by Civic Consulting on behalf of the European Commission in 2016. The aims with the Fitness Check of EU consumer and marketing law were threefold: first, it was to evaluate whether the horizontal consumer and marketing rules remain fit for purpose. Second, it was to identify excessive regulatory burdens, overlaps, gaps, inconsistencies, and/or obsolete measures that have appeared over time, and third, it was to determine whether there was a need for further action at EU level to ensure consumer protection (European Commission 2017b). Since the aim was to evaluate the functioning and potential future directions of EU consumer policy, the country-specific data collected as part of the Fitness Check represents a unique opportunity to study country and regime differences in preferences in key issues in EU consumer policy. Such data that enable direct comparison of the preferences of government actors were collected through an open public consultation.

The open public consultation was carried out from 12 May to 12 September 2016 and received 436 responses from stakeholders across the EU. The consultation was structured in three questionnaires. The consumer questionnaire was available only to respondents indicating that they were “a citizen/consumer.” The business questionnaire was available only to respondents indicating that they were “a company (or group of companies).” The “full” questionnaire was targeted at the other types of respondents, such as government actors, consumer associations, academics etc., and was optional for the consumers and businesses. All questionnaires used closed questions and gave respondents the possibility to comment in each section (Civic Consulting 2017). For the purposes of this study, I use the replies to the full questionnaire, as I am interested in the views of government actors representing country positions. Table 2 gives an overview of the actors in the sample by country. In this sample, one actor has been recoded from “other” to “public enforcement authority” (Instituto de Consumo de Extremadura in Spain). One of the government actors who replied to the consultation chose not to make its response available to the public and is therefore excluded from the dataset made available by the European Commission. Our sample consists of 24 government actors from 19 different countries. When several actors in one country have replied, the average scores of these actors are calculated and used in the analysis. The data is analysed and interpreted qualitatively as the number of unique replies does not permit the use of quantitative methods.

The “full” questionnaire of the open public consultation consists of 16 batteries of questions and one single question. The answer options to all questions/statements are either five-point scales or four-point scales with an additional “No opinion/don’t know” category. The original four-point scales have been recoded into five-point scales by making the “No opinion/do not know” category into a neutral category. The “no opinion/don’t know category” were also recoded into a neutral category for the questions/statements already using a five-point scale. Questions and statements are also recoded so that they all go in the same direction, from negative (1) to positive (5). In order to simplify the analysis while preserving as much information as possible, we have constructed several indexes measuring broader phenomenon. These have been constructed based on factor and reliability analyses of data from all actors replying to the “full questionnaire” in the open public consultation (N = 152). The variables have been categorized into four topics: (1) understanding of problems, (2) satisfaction with EU consumer policy, (3) regular tools/policy instruments, and (4) solutions. As all questions relate to EU consumer policy, these four topics are used as operationalizations of positions to EU consumer policy. The detailed operationalizations of variables are presented in Appendix A.

Interviews with National Stakeholders

In order to gather more in-depth data on national preferences in EU consumer policy, on the potential differences between countries and classifications of regimes and on the potential reasons for differences, data were collected through interviews with key national stakeholders. Members of the European Commission expert group “Consumer Policy Network (CPN)” were sought recruited to the study since this group gathers relevant government actors from all EU member states as well as EEA states. The official mission of this group is to “facilitate exchange of information and good practice between consumer policymakers in the Member States”, and one of the aims is to “assist the Commission in the preparation of legislative proposals and policy initiatives” (European Commission 2018b). In order to be able to meet with as many representatives as possible, we were granted access to a network meeting in Lisbon in June 2018. We were not given access to the contact information of the members, but we got the opportunity to distribute a small survey requesting the participants who were willing to participate in an interview to share their contact information with us before the meeting. Nine participants answered the survey. Some participants said that they were not willing to be interviewed, but that they could answer a survey in writing after the network meeting. During the 2-day meeting, we interviewed participants from seven countries. A survey based on the same interview guide were sent to participants from two countries who had agreed to this option, and a general request to participate in the survey was sent to the ministries of another few key countries. Informants from two countries answered the survey. The Norwegian participant was interviewed later in Oslo. Table 3 gives an overview of the interview details, and the questions from the interview guide are presented in Annex B. Only the institutions the informants represent, and not the names of the informants, are disclosed as they were asked to express themselves through their role as CPN members. The interviews were analysed using Nvivo 12.

Data Limitations

It was voluntary to participate in the open public consultation, and although the European Commission urged government representatives in all countries to participate, government representatives in some countries chose to not reply to the consultation. The dataset used in this article therefore lacks replies from several countries, i.e., Bulgaria, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, Poland, Slovenia, Sweden, and Iceland. Three of these countries were covered through the stakeholder interviews, while eight countries are not covered. The positions of these countries and their place in the regime classification therefore cannot be investigated other than through the perceptions of the other stakeholders interviewed.

For the purposes of this analysis, the replies from different types of national actors, “consumer enforcement authority”, “public enforcement authority in a specific area”, and “government authority in charge of consumer policy” have been merged into the main category “government actor.” When several actors in one country have replied, the average scores of these actors are used in the analysis. This can represent a bias in the sample as different types of actors within a country may have different views and opinions. A comparison of the within-country replies shows that there often are differences between the national actors, but that these are small and mostly limited to one score differences on a scale from 1 to 5. In 3% of the replies, the answers differ with three scores, while they differ with two scores in 13% of the replies. The issue of within-country differences in positions to EU consumer policy was also discussed with the stakeholders as part of the interviews, who indicated that this was not considered as a substantial challenge. Nevertheless, since the regime scores are based on relatively few replies, the scores are vulnerable to these potential within-country differences as well as other factors that may influence the replies, such as the extent to which the views expressed in the replies were consolidated within the organization and the country as such. Despite these limitations, the data provides a unique opportunity to study country and regime differences in preferences in key issues in EU consumer policy, as little other data that is suitable for direct comparison is available on the preferences of government actors.Footnote 3 The data have also played an important role in the European Commission’s Fitness Check of EU consumer and marketing law (European Commission 2017b).

Similar to the data from the open public consultation, the data from the stakeholder interviews are also limited as we were unable to interview representatives from all Member States. The country representatives in the Consumer Policy Network, which we interviewed, are usually confronted with policy issues at a fairly early stage in the decision-making process and are not necessarily the same as the ones who are negotiating proposals in the European Council. The preferences and interests promoted in the CPN meetings can be more influenced by the individuals who meet there and the tradition of the organization they represent and will not always represent what turns out to be the official position of the country. The fact that not all countries would be covered and that the informants participated in an early stage of the decision-making process influenced the focus as well as the interpretations of the interviews, but it is still possible that this limitation has resulted in omission of important views, considerations, and reflections regarding grouping of countries.

Analysis and Results

Results from the Open Public Consultation

Differences between countries and groups of countries can be investigated in several ways. Both Repo and Timonen (2017) and Nessel (2019) have used p values from tests for equality of means. This approach is of limited value when investigating the data from the open public consultation, both because of the limited amount of unique replies and more importantly because the p value is an indicator of the probability that the difference between the population means is at least as large as what has been observed in the sample. The results, as presented in Table 4, show the results of the government representatives’ replies to the open public consultation, and these representatives constitute the population we are interested in. The similarities and differences between the regimes are therefore analysed mainly based on the observed scores and the standard deviations within and between regimes. Lower standard deviations within regimes indicate that the country representatives agree more with each other, and higher standard deviations between regimes indicate greater differences between the regimes. For the purposes of this analysis, the variables in the open public consultation were categorized into four topics, and the results in Table 4 are presented by these topics.

Overall Similarities and Differences Within Regimes

The results show that for most of the variables investigated, the variations in the country representatives’ replies are lower within the country groups than the variations within the whole sample. This indicates that, on average, the countries grouped together in a regime are more similar to each other than to the whole sample of countries. This can also be observed by comparing the average standard deviations within the regimes with the average standard deviations for all countries. However, when considering all variables, the Anglo regime stands out as the one with highest average standard deviation, higher than the average standard deviation for all countries, and thus the lowest internal agreement. This indicates that the evidence for an Anglo regime is weak. The other regimes all have lower average standard deviation within the regimes than the average standard deviation for all countries.

Issues Characterized by Weak Regime Differences

For many of the variables, the difference within the regimes was larger than the differences between the regimes, and for four variables, the differences within the regimes were larger than the differences within the whole sample. This indicates that there are no clear regime differences for these issues.

For the first topic, understanding of problems, no regime differences can be observed for the variable “understanding of consumer law”, and all regimes give high scores to this variable. This indicates that most countries agree that consumers’ and traders’ limited understanding of consumer law is an important problem for protecting the rights of consumers.

For the second topic, measuring satisfaction with EU consumer policy, no regime differences can be observed for all but one variable. The results furthermore show that overall all regimes are either moderately or fairly satisfied with EU consumer policy, except for a weak dissatisfaction within the Eastern European regime with the protection of businesses.

For the third topic, regulatory tools/policy instruments, the regime differences are weak for the variables measuring the perceived effectiveness of self- and co-regulation initiatives, where all but the Germanic regime consider the tool as moderately effective. Similarly, the differences between the regimes are weak when it comes to the perceived effectiveness of third-party assisted enforcement, where all regimes consider this to be either moderately or very effective.

Finally, for the fourth topic, solutions, the regime differences are weak when it comes to suggested ways to strengthen consumer protection, where all regimes are positive. The regime differences are also weak when it comes to suggested ways of simplifying the presentation of information to consumers, where all regimes but the Germanic regime either moderately or fairly strongly agree, and the differences are weak when it comes to suggested ways of strengthening the protection of businesses.

Issues Characterized by Stronger Regime Differences

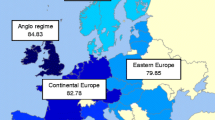

On the other hand, the results also show that the differences between the regimes are either higher or almost the same as the differences within the regimes for six variables, presented in Fig. 1. This can be interpreted as an indication of regime differences.

For the first topic, understanding of problems, the standard deviations between the regimes are almost the same as the average standard deviation within the regimes for two variables.Footnote 4 First, there is a difference between the regimes when it comes to their perception of how important the problem of inefficient enforcement of consumer law is for protecting the rights of consumers. On average, this is considered most problematic by the countries belonging to the Eastern European regime (4.26 on a sale from 1 to 5) and least problematic by the countries belonging to the Nordic regime (3.38). Furthermore, there is a difference between the regimes when it comes to their perception of how important the problem of complex consumer law is for protecting the rights of the consumers. On average, this is considered as most problematic by countries belonging to the Eastern European regime (3.79) and the Franco-Roman regime (3.75) and least problematic by the countries belonging to the Germanic (2.0) and Southern-European regime (2.25).

For the second topic, satisfaction with EU consumer policy, indications of regime differences are found for only one variable—perceptions of the impact of EU consumer and marketing law on the quality and availability of products. On average, countries belonging to the Eastern European regime are most positive (3.79) while Austria, belonging to the Germanic regime, is least positive (2.33). The scores for the Franco-Roman (3.17), the Anglo (3.22) and the Nordic (3.28), and the Southern European regime (3.33) are fairly similar.

For the third topic, regulatory tools/policy instruments, the results indicate regime differences for two issues. The first is the perceived effectiveness of sector-specific injunctions taken by consumer organizations and public bodies to stop infringements of consumers’ rights, where countries belonging to the Anglo regime (2.72) are least positive while Austria, belonging to the Germanic regime (5.0) is most positive.Footnote 5 The second is the perceived effectiveness of injunctions sought against various illegal practices. On average, countries belonging to the Eastern European (3.21) and the Nordic (3.37) regime are least positive while countries belonging to the Southern European regime (5.0) are most positive.Footnote 6

Finally, for the fourth topic, solutions, the results indicate regime differences when it comes to preferences regarding the potential for further standardization of EU consumer and marketing rules. This is the variable where the standard deviations between the regimes are greatest. This is strongly driven by the low score given by Austria, belonging to the Germanic regime (1.0), clearly rejecting that further standardization is a good idea. On average, the countries belonging to the Nordic regime (3.0) are neither negative nor positive, while the countries belonging to the Eastern European (3.60), the Anglo (4.11), the Franco-Roman (4.55), and the Southern-European regime (4.67) are fairly or very positive to further standardization.

Results from the Stakeholder Interviews

Most of the interview informants expressed satisfaction with the EU as the driver of European consumer policy, and many pointed to examples of policies and legislation benefiting the consumer that most likely would not have been introduced in their country had it not been for the EU. Nevertheless, the informants also pointed to problematic issues with EU consumer policy. Several informants argued that the consumer legislation is lagging too far behind a very fast digital development and general market development and that the legislation on some areas is outdated. This was highlighted as a particularly challenging topic for the development of consumer policy at EU level, as the process of developing policy and consumer legislation is particularly meticulous when 28 Member States need to reach consensus. Several informants also emphasized the differences in enforcement of consumer legislation across the Member States as a key challenge for EU consumer policy.

A topic that has been key to EU consumer policy since it was first established, and which still represents one of the key challenges for achieving common agreement between the Member States, is the level of harmonization of European consumer policy. The issue of standardization of consumer law as a potential priority for future EU consumer policy was also the issue where the results from the open public consultation indicated the greatest differences between the regimes. This was therefore one of the key issues discussed in the interviews and the informants’ preferences regarding the level of harmonization varied. Due to the importance of this topic, the further presentation of the results from the interviews is mostly focused on differences between countries and regimes in preferred harmonization level and the reasons for these differences.

Perceptions of the Level of Harmonization

According to interview informants, nordic countries are split when it comes to preferences for the level of harmonization. Sweden and Denmark are fairly positive to full harmonization, while Finland and Norway take a more pragmatic approach. Both Finland’s and Norway’s official approach is to consider the level of harmonization on a case to case basis, while Sweden and Denmark are more fundamentally positive to full harmonization.

The informants from the Eastern European countries we talked to all emphasized that they, as a starting point, were in favour of full harmonization. Nevertheless, the informant from the Czech Republic mentioned that their position is not as solid as it used to be, “because sometimes it goes too far, even for us”. Some informants specifically highlighted that the Baltic states traditionally had been in favour of full harmonization.

The only representative from a Southern European country interviewed, Italy, clearly stated to be in favour of full harmonization and thinks that the EU should go further.

Two informants argued that the UK, which in this case represents the Anglo regime, traditionally had been very much in favour of the single market and therefore also in favour of full harmonization.

Germany, representing the Germanic regime, was by one informant used as an example of a big country with a long consumer protection tradition which is not in favour of full harmonization as they want to keep their own rules.

Based on the interviews, the countries belonging to the Franco-Roman regimes seems to be more split in their position to harmonization of consumer law. Luxembourg was highlighted by some informants as being in favour of full harmonization. The Netherlands was somewhat more pragmatic. They stated that they in principle are in favour of full harmonization as it is important for achieving a true single market, but that it is difficult to achieve a high enough standard. Furthermore, they argued that it could be difficult to convince national stakeholders that it might be worthwhile to reduce the level of consumer protection on some matters in order to achieve full harmonization. Finally, France, similar to Germany, was by some informants used as an example of large countries with a long consumer tradition, which is not in favour of full harmonization. This was confirmed by the French informants as well who emphasized that it is important that Member States can preserve existing protection levels.

The Stakeholders’ Own Grouping of Countries

The interview informants were asked if they thought it was possible to group countries according to their positions and interests in EU consumer policy, and if so—how they would group the countries. A clear finding from the interviews is that there is no strong consensus regarding the first question. Some informants argued that it was not possible to group countries on a general basis as interest coalitions are too issue specific, some informants emphasized that coalitions are issue specific, but were still able to group countries on more specific issues or at a more general level. Finally, some informants were of the perception that clear interest constellations exist and that countries have consistent positions in EU consumer policy.

Most of the informants who thought that it was possible to group countries, distinguished a North-South dimension. The Italian informant thought that countries, at an overall level have fairly consistent positions in EU consumer policy, and distinguished between Latin-, Central-, and Northern European countries. The Latvian informant emphasized that the positions are, to some extent, issue specific and that it depends on the engagement and interest of the country in the specific topic, but that an overall distinction can be made along the North-South dimension. However, this informant also thought that it was possible to distinguish smaller groups that are often thinking similarly. This can be the Nordic countries, the Baltic countries, and the Southern European countries, and both Germany and the UK represent countries that are often quite pragmatic. The reason emphasized by the Latvian informant for why these countries often think similarly is the different traditions of the (groups) of countries. The interview informant from Denmark also distinguished between several groups of countries at a rather general level. According to the Danish informant, the Nordic countries often, but not always, agree on important topics. Other countries that often seem to agree with each other are the Benelux countries and Eastern European countries. Furthermore, Denmark often takes different positions than France and Germany. The Danish informant argued that this might be related to the very different legal system in France and the very different business structure and organization of consumer interests in Germany, compared to Denmark.

The informants from the Netherlands, Norway, Finland, and the Czech Republic argued stronger for coalitions being issue-specific, but still thought that it was possible to somehow group countries on more specific issues. The informants from the Netherlands argued that on the specific issue of tackling dual quality in consumer products, which is part of the 2018 EC proposal on a new deal for consumers (European Commission 2018a), there is a clear East-West dimension in the countries’ positions. The same informants also argued that there is a big difference between countries when it comes to enforcement and that Eastern European countries are struggling more than Northern and Western European countries. This was also supported by the Danish informant, who argued that both Eastern European and Southern European countries are struggling more with enforcement because they have fewer resources available for this purpose.

The Norwegian informant also emphasized that coalitions are rather issue-specific, but indicated that the Nordic countries often have coinciding interests. To illustrate that coalitions often are issue-specific, the Norwegian informant mentioned the European Commission’s proposal on fully harmonizing the legal guarantee period for sales of goods at two years (European Commission 2017a), as opposed to keeping this as a minimum harmonized provision as it was in the former consumer sales and guarantees directive (CSGD) (Directive 1999/44/EC 1999). On this issue, the Norwegian position was that they wanted to keep their existing legal guarantee period of five years for products intended to last for more than five years. When seeking to influence the negotiations, it was, according to the Norwegian informant, natural to talk to other countries that were in the same position of having national rules going further than the EC proposal, but also other countries that could be inclined to support them on this issue. In this matter, it was also natural to talk to countries with a grassroots approach to consumer protection—such as Spain, Portugal, Italy, and France—because although they do not necessarily have the same level of protection in their countries, they might think that it is unacceptable to reduce the consumer protection level in another country. This indicates that Southern European countries potentially can be considered as a group with similar interests as well. Furthermore, the Norwegian informant mentioned that some of the new Member States, mostly Eastern European countries, can be more open to more creative suggestions from the European Commission—perhaps because they have a limited national tradition for consumer policy. Finally, the Norwegian informant mentioned that Germany and Austria have many similarities in the way they are organized and that the UK is a somewhat special case as they are both eager to be “cutting red tape for business” and have a high level of consumer protection.

The Finnish informant also emphasized that coalitions often are issue specific, and exemplified this with the strong alliance they have had with Poland and France—countries that are not usually grouped together—on consumer credit because similar to Finland, these countries have had really advantageous rules on early repayment. Nevertheless, also the Finnish informant argued that although Nordic countries do not always have common or similar positions in EU consumer policy, they often do since the Nordic states have many common provisions in their legislation that makes it easier to negotiate with each other.

Finally, informants from two countries, France and the Czech Republic, stated that interest coalitions are too issue specific to be able to make overall categorizations. However, according to the French informant, the countries’ interests and goals are often a function of the countries’ legal tradition. What counts as most important for countries when establishing interest coalitions, according to the Czech informant, is to find partners with sufficient amount of votes in the council.

Reasons for Differences

As indicated in the previous section, the informants pointed to several reasons for why countries’ preferences in EU consumer policy vary. For some informants, it was difficult to talk about differences between countries in very general terms, and the differences in the countries’ positions towards the level of harmonization of rules were then used as a proxy to discuss differences in country preferences. The results should therefore be interpreted as pointing to reasons for differences in country preferences regarding the level of harmonization of EU consumer policy and legislation as an expression of preferences in EU consumer policy.

In the interviews, five main reasons for differences between countries were emphasized by the informants, some potentially more important than others. These five reasons, and how they influence the countries’ preferences in EU consumer law and policy, are illustrated in Fig. 2.

The reason for differences between countries’ preferences in EU consumer policy in general, and more specifically regarding the level of harmonization, mentioned by most informants was the existing level of consumer protection in the various countries. Having a higher national consumer protection level than what is proposed by the European Commission is often a reason for why countries are negative to full harmonization. However, since the national levels of consumer protection can be seen as a consequence of many other factors, this is presented as a mediating variable in Fig. 2, influenced by the other four reasons for differences in preferences in EU consumer law and policy.

Several informants pointed to reasons relating to the organizational structure of the country. This could be differences in legal traditions, regulatory traditions, the history of consumer policy in the countries, and the country’s political system. Legal traditions were seen as important as it can be more difficult to harmonize aspects that are covered by private law in some countries, as it influences the desired levels of detail in the legislation and because it impacts how legislation is enforced which is another key aspect of EU consumer policy. The regulatory tradition was emphasized by some informants as a potentially important influencing factor as it governs the role of societal actors and their ability to influence a country’s consumer policy. One example used was that businesses are more involved in the decision-making processes in, e.g., the Netherlands than in, e.g., France, since the Netherlands is characterized by a more corporatist structure than France which is characterized by more centralist structure where the state is seen as a guarantor of citizen and consumer rights. Furthermore, the political system was mentioned by one informant who suggested that it perhaps could be more difficult to harmonize consumer policy in countries with a federal system compared to countries with a unitary system. The history of consumer policy was emphasized by several informants who argued that proposals from the EU that would create a stir in the national system would not be very well received, and that (especially controversial or so-called creative) proposals from the EU would perhaps be easier to get through to newer Member States with shorter and less established consumer policy traditions.

The third potential reason for differences in countries’ positions to EU consumer policy emphasized by the informants is the size of the consumer sector and the resources available at the national level. This is especially the case for EU initiatives that requires a lot of activity and resources from the national level—if the country has limited resources for consumer policy activities, such as activities in the consumer protection cooperation (CPC), it is more likely to be negative to the EU proposal. Furthermore, several informants point to the fact that the national resources available—the amount of people working with consumer policy in the country—has an impact on how able the country is to get involved themselves and to involve the relevant national actors in the decision-making process at EU level. It might therefore be easier for stakeholders to be heard, especially businesses with strong lobby groups, in countries with relatively much resources for consumer policy. Finally, countries that have relatively much resources available to consumer policy might be more sceptical towards full harmonization as long as they are of the perception that EU consumer policy develops too slowly compared with the developments of the markets. These countries might be interested in being able to meet new challenges at the national level while awaiting solutions at the EU level.

The fourth potential reason for differences pointed to by the informants is the position of national economic interests, such as businesses and industry, and the country’s export opportunities. When a country hosts strong export-oriented companies that can benefit from full harmonization of consumer legislation, this might affect the general position of the country. Furthermore, some informants also point to the strength of lobby groups as a potential reason for why a country takes a certain position in EU consumer policy.

The fifth and final reason mentioned by some informants is the partisanship of the national government in the country in question. Although consumer policy is not the most politicized policy field in many countries, the party or coalition of parties in power might influence the country’s prioritization of consumer policy compared with other policy areas as well as the prioritizations of issues within consumer policy.

Discussion

Regime Differences

The analyses of the results show that for most issues investigated in the open public consultation, the variations in the country representatives’ replies are lower within the regimes than within the whole group of countries. This indicates that, on average, the countries grouped together in a regime are more equal to each other than to the whole sample of countries. The exception is the Anglo regime, consisting of the UK, Malta, Cyprus, and Ireland, where the average standard deviation within the regime was greater than the average standard deviation in the whole sample. Furthermore, the results show differences between the regimes for some, but not all, issues covered in the open public consultation. This can be interpreted in several ways. It can indicate that the pre-defined classification of regimes is not accurate enough or that categorizing countries into regimes has limited utility. It can also indicate that the differences between the regimes are limited, especially compared with the differences within the regimes, and that it does not make sense to investigate preferences and perceptions from the regime perspective. Finally, this result can also be used as an indicator of where the differences between the countries and regimes are greatest and hence which issues that should be investigated further. Based on the average within-regime differences being smaller than the variations for all countries and the results generated through different methods being, at least partly, consistent, this article leans on the third interpretation. The results are thus interpreted to partly support the predetermined classification of countries into regimes and are used to identify areas and issues where the regimes differ in their preferences in EU consumer policy.

The results show that the area where the regimes differ the most is on the issue of harmonization of consumer and marketing law at EU level. The results from the open public consultation and the stakeholder interviews are to a certain extent overlapping, but they are not identical. The results were consistent for both the Anglo countries and the Southern European countries as the results from both the stakeholder interviews and the open public consultation indicate that the countries belonging to these regimes are in favour of standardization of consumer law and policy. However, countries belonging to these regimes do not consider complex consumer law as a very substantial problem for protecting the rights of consumers. The results were also fairly consistent for the Germanic regime as countries belonging to this regime were considered as more negative to standardization. They also did not consider complex consumer law as major problem for protecting the rights of consumers. On the other hand, the results for the Nordic, the Eastern European, and the Franco-Roman regime were more complex. According to the results from the stakeholder interviews, the preferences of the countries belonging to the Nordic regime vary, as Denmark and Sweden were considered as more positive to full harmonization than Finland and Norway. This is only partly confirmed by the results from the open public consultation as Norway right enough is the least positive (2.0 on a scale from 1 to 5), while Denmark neither agrees nor disagrees (3.33) and Finland is slightly positive to further standardization of consumer law (3.66). On the other hand, the results from the open public consultation also show that complex consumer law is perceived as a greater problem for protecting the rights of consumers by Denmark (4) than by Finland (3.0) and Norway (1.5), which can be interpreted as supporting to the results from the stakeholder interview. Also, the countries belonging to the Franco-Roman regime seem to be somewhat split in their position to standardization of consumer law based on the results from the interviews, as France is considered to be less positive than the other countries to full harmonization. However, the results from the open public consultation indicate rather that the countries in this group that replied to the consultation are all fairly positive to standardization (from 4.0 to 5.0 on a scale from 1 to 5). Furthermore, they all consider complex consumer law to be a significant problem for protecting the consumers (from 3.5 to 4.0). For the Eastern European regime, the results from the open public consultation indicate that, overall, countries belonging to this regime are slightly positive to standardization of consumer law (3.6). Of the countries in this group that answered the survey, Lithuania is most positive (4.67), followed by Croatia (4.33), Romania (4.33), and the Slovak Republic (3.67) and Latvia (3.16). Estonia (2.67) and the Czech Republic (2.33) are negative to the proposals for further harmonization of EU consumer law. All countries, except Croatia and the Slovak Republic (3.0), consider complex consumer law as a significant problem for protecting the rights of consumers (from 3.75 to 5.0). This is partly in line with the results from the stakeholder interviews, as most informants argued that Eastern European countries traditionally had mostly been in favour of full harmonization, but that the position for some countries, such as the Czech Republic, was no longer as solid as it used to be.

Taken together, these results show that the issue of harmonization of EU consumer and marketing law is complex and that the regime positions, even the country positions, are not clear cut. Nevertheless, the results indicate that it is reasonable to make use of the regime approach when analysing these countries’ positions to EU consumer policy as there are clear similarities between the countries within a regime. Analysing the preferences of regimes, rather than those of individual countries, is a tool that enables the handling of many analytical units and variables. Nuances are lost, but the tool enables identification of key differences as well as explanations and causes of these differences. Acknowledging differences between regimes and identifying the underlying reasons for the differences thus provide opportunities to tackle difficulties in reaching agreement at EU level.

Reasons for Differences

The reasons for differences between countries and regimes’ preferences in EU consumer policy, pointed to by the stakeholders, give support to the rationales of the initial categorization of countries into regimes and thus to key aspects of previous classifications of European consumer policy regimes. However, the stakeholders interviewed also point to other reasons that are not substantially covered by the reasoning of Trumbull (2006a, 2006b, 2012), Cseres (2005), or Micklitz (2003).

Trumbull and Cseres place much focus on the discourses about the consumer’s status and abilities, and Trumbull furthermore emphasizes the importance of the power distribution among the key national actors. This is used to explain why consumer interests have been institutionalized in a certain way and thus the shaping of national consumption regimes. Micklitz (2003) points to differences in legal traditions between countries when identifying models of consumer policy in Europe. Some of the reasons for differences in countries’ position to EU consumer policy pointed to in the stakeholder interviews, as presented in this article, coincides with the rationales for these previous regime classifications. This is especially the case for differences in organizational structure, which includes differences in legal traditions, regulatory traditions, the history of consumer policy in the countries, and the countries’ political system.

The other reasons for differences pointed to by the stakeholders, such as the national economic interests and the partisanship of national governments, are not well integrated in the existing regime classifications. However, international relation research on the formation of negotiating positions has shown that structural and domestic interests, such as national economic interests, are important shaping factors (e.g., Bailer 2011; Putnam 1988). The partisan preferences of governments have also been found relevant for explaining policy preferences of governments in international relations (Schmidt 1996), although the opposite has also been argued (Bailer 2011; Zimmer et al. 2005). The third variable pointed to by the stakeholders, resources and size of the consumer sector, has not been emphasized as an important explanatory factor for consumer policy preferences in previous literature, except for indirectly as being part of how consumer interests have been institutionalized.

Finally, it is suggested in this article that all of these variables might influence the country’s consumer protection level, and that this level should in itself be seen as an important factor when seeking to explain country preferences in EU consumer policy in general and specifically preferences regarding harmonization of EU consumer and marketing law. The importance of the existing consumer protection level is supported by Bailer (2011:463) who finds that peoples’ perceptions of one’s own country’s level of consumer protection explains a significant share of Member States’ positions in internal market negotiations.

The result from the stakeholder interviews thus indicate that the variables that have been used to distinguish the existing policy regimes only constitutes some of the variables that influences countries’ preferences in EU consumer policy.

Conclusions, Limitations, and Recommendations for Future Research

Together, the results from the analysis of the data from the open public consultation and the stakeholder interviews indicate that it makes sense to study preferences in EU consumer policy from a regime perspective as there seems to be clear differences between most of the identified regimes. Furthermore, the results show that the classifications from previous literature on consumer policy regimes (Cseres 2005; Micklitz 2003; Repo and Timonen 2017; Trumbull 2006a, 2006b, 2012) are a valid starting point for the identification of these regimes. From this, it can be deduced that the heritage of national economies and institutions likely influence national actors’ preferences in EU consumer policy, despite the recent decades’ convergence in national consumer policies caused by European integration. However, the data used in this article has its limitations, of which the key limitation is that we lack data from all Member States, and the results should therefore be interpreted with caution. Nevertheless, this research represents an important first step in investigating the usefulness of studying country preferences in EU consumer policy through a regime approach and makes it possible to make some recommendations regarding how preferences in EU consumer policy should be studied further.

The limitations pointed to in the analysis indicate that clear conclusions cannot be drawn regarding the accuracy of the regime classification presented in Table 1. This, and potentially other, regime classifications should therefore be further investigated through, e.g., testing on larger and more robust datasets. Furthermore, as the results from the stakeholder interviews also point to other potential factors explaining differences between countries and regimes, the regime classification should be tested further by adding more variables to the basis for the classification. Future studies should also aim to generate deeper knowledge about the potential effects of the various factors that can explain countries’ and regimes’ preferences in EU consumer policy, both the ones pointed to in previous research and the ones proposed in the stakeholder interviews. This can be done by gathering larger datasets that enable operationalization of the variables identified as potential explanatory factors for positions to EU consumer policy and to test these against positions of countries in several concrete cases at several stages in the policy-making and/or legislative process. This would generate better and deeper knowledge about the potential effects of the various explanatory factors—knowledge that could make it easier in the future to come up with solutions at EU-level that have good prospects for success.

Finally, although the analysis of the results from the open public consultation focused on four topics important to EU consumer policy, this article has placed a special focus on the issue of harmonization and standardization of consumer policy and law as this seems to be the most important and most controversial issue. Future studies investigating the relevance of the regime approach and the robustness of the regimes identified in this article should also place a particular focus on the other topics that are key to EU consumer law and policy.

Change history

19 October 2020

The original article unfortunately contains cut-off Appendix A and missing Appendix B.

Notes

One of the latest examples is the negotiations on the European Commission’s amended proposal for a directive on certain aspects concerning contracts for the sales of goods, where a key suggested change was to provide for maximum harmonization and thereby prohibiting Member States from introducing a higher level of consumer protection than envisaged in the directive (European Commission 2017a). However, when the new sales of goods directive was adopted in 2019 it left some room for Member States to maintain the level of consumer protection already applied at national level, e.g., regarding the time limits for the guarantee period and regarding the burden of proof in case of non-conformity of the good (Directive (EU) 2019/771 2019). Furthermore, although the scopes of the Directives generally have been enhanced, the harmonization level for certain issues in two originally fully harmonized directives, the Unfair Commercial Practices Directive (2005/29/EC) and the Consumer Rights Directive (2011/83/EC), were reduced in the recently adopted Modernisation Directive (Directive (EU) 2019/2161 2019).

Including the United Kingdom although they joined the EU later and voted to leave the Union in 2016.

An exemption is clearly data on how countries have voted on consumer policy issues in the European Parliament and the Council. Nevertheless, given that the proposals that are voted over have gone through substantial negotiations between the Member States and that these data only indicates support or not to a complete “package”, voting data is less suited to distinguish country and regime preferences regarding specific issues in EU consumer policy.

The standard deviations between the regimes are higher than the average standard deviation within the regimes when Anglo is excluded.

Due to high internal disagreement (SD 1.60) within the Anglo regime, the distance between the average standard deviation within regimes and the standard deviation between regimes increases when the Anglo regime is excluded.

Due to high internal disagreement (SD 1.41) within the Anglo regime, the distance between the average standard deviation within regimes and the standard deviation between regimes increases when the Anglo regime is excluded.

References

Bailer, S. (2011). Structural, domestic, and strategic interests in the European Union: Negotiation positions in the Council of Ministers. Negotiation Journal, 27(4), 447–475.

Cafaggi, F., & Micklitz, H.-W. (2009). New frontiers of consumer protection: The interplay between private and public enforcement. Antwerp: Intersentia.

Consulting, C. (2017). Study for the Fitness Check of EU consumer and marketing law. Final report part 2 - report on the open public consultation. Brussels: European Commission.

Cseres, K. J. (2005). Competition law and consumer protection (Vol. 49, European monographs). The Hague: Kluwer.

Elgström, O., Bjurulf, B., Johansson, J., & Sannerstedt, A. (2001). Coalitions in European Union negotiations. Scandinavian Political Studies, 24(2), 111–128.

Esping-Andersen, G. (1990). The three worlds of welfare capitalism. Cambridge: Polity Press.

European Commission. (2012). COM (2012) 225 final. European Commission: A European Consumer Agenda - Boosting confidence and growth. Brussels: European Commission.

European Commission. (2014). Consumer market study on the functioning of the market for second-hand cars from a consumer percpective. No EAHC/FWC/2013 85 01. Luxembourg: Publications Office for the European Union.

European Commission. (2017a). COM (2017) 637 final. European Commission: Amended proposal for a directive on certain aspects concerning contracts for the sales of goods. Brussels: European Commission.

European Commission. (2017b). COM SWD (2017) 209 final. Brussels: European Commission.

European Commission. (2018a). COM (2018) 183 final. European Commission: A new deal for consumers. Brussels: European Commission.

European Commission. (2018b). Register of commission expert groups and other similar entities. Consumer Policy Network (E00861). Retrieved from: http://ec.europa.eu/transparency/regexpert/index.cfm?do=groupDetail.groupDetail&groupID=861&NewSearch=1&NewSearch=1. (accessed 3 October 2018).

Hasenclever, A., Mayer, P., & Rittberger, V. (1997). Theories of international regimes (Vol. 55). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Howarth, D., & Sadeh, T. (2010). The ever incomplete single market: Differentiation and the evolving frontier of integration. Journal of European Public Policy, 17(7), 922–935.

Kaeding, M., & Selck, T. J. (2005). Mapping out political Europe: Coalition patterns in EU decision-making. International Political Science Review/ Revue internationale de science politique, 26(3), 271–290.

Keohane, R. O., & Nye, J. S. (2012). Power and interdependence (4th ed., Longman classics in political science). Boston: Longman.

Krapohl, S. (2007). Thalidomide, BSE and the single market: An historical-institutionalist approach to regulatory regimes in the European Union. European Journal of Political Research, 46(1), 25–46.

Krasner, S. D. (1982). Structural causes and regime consequences: Regimes as intervening variables. International Organization, 36(2), 185–205.

Mattila, M., & Lane, J.-E. (2001). Why unanimity in the council? A roll call analysis of council voting. European Union Politics, 2(1), 31–52.

May, P. J., & Jochim, A. E. (2013). Policy regime perspectives: Policies, politics, and governing. Policy Studies Journal, 41(3), 426–452.

McGregor, S. L. T. (2017). Bringing complexity and convergence governance to consumer policy. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 41(6), 685–695.

Micklitz, H.-W. (2003). The necessity of a new concept for the further development of the consumer law in the EU. German Law Journal, 4(10), 1043–1064.

Moravcsik, A. (1997). Taking preferences seriously: A liberal theory of international politics. International Organization, 51(4), 513–553.

Nessel, S. (2019). Consumer policy in 28 EU Member States: An empirical assessment in four dimensions. Journal of Consumer Policy, 1–28.

Pierson, P. (2000). Increasing returns, path dependence, and the study of politics. American Political Science Review, 94(2), 251–267.

Pollack, M. A. (1997). Representing diffuse interests in EC policy-making. Journal of European Public Policy, 4(4), 572–590.

Putnam, R. D. (1988). Diplomacy and domestic politics: The logic of two-level games. International Organization, 42(3), 427–460.

Repo, P., & Timonen, P. (2017). Regime market performance analysis: Informing European consumer policy. Journal of Consumer Policy, 40(1), 125–143.

Schmidt, M. G. (1996). When parties matter: A review of the possibilities and limits of partisan influence on public policy. European Journal of Political Research, 30(2), 155–183.

Strünck, C. (2005). Mix-up: Models of governance and framing opportunities in U.S. and EU Consumer Policy. Journal of Consumer Policy, 28(2), 203–230.

Thomson, R., Boerefijn, J., & Stokman, F. (2004). Actor alignments in European Union decision making. European Journal of Political Research, 43(2), 237–261.

Trumbull, G. (2006a). Consumer capitalism: Politics, product markets, and firm strategy in France and Germany. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Trumbull, G. (2006b). National varieties of consumerism. Jahrbuch für Wirtschaftgeschichte / Economic History Yearbook, 47(1), 77–94.

Trumbull, G. (2012). Three worlds of consumer protection. In G. Trumbull (Ed.), Strength in numbers: The political power of weak interests (pp. 1–33). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Weatherill, S. (2013). EU consumer law and policy. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing, Incorporated.

Wilson, C. A. (2000). Policy regimes and policy change. Journal of Public Policy, 20(3), 247–274.

Zimmer, C., Schneider, G., & Dobbins, M. (2005). The contested council: conflict dimensions of an intergovernmental EU institution. Political Studies, 53(2), 403–422. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9248.2005.00535.x.

Legislation

European Union

Directive (EU) 2019/2161 (2019). Amending council directive 93/13/EEC and directives 98/6/EC, 2005/29/EC and 2011/83/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council as regards the better enforcement and modernisation of union consumer protection rules. OJ L 328, 18.12.2019 (p. 7–28)

Directive (EU) 2019/771 (2019) on certain aspects concerning contracts for the sale of goods, amending Regulation (EU) 2017/2394 and Directive 2009/22/EC, and repealing Directive 1999/44/EC. OJ L 136, 22.5.2019 (p. 28–50)

Directive 1999/44/EC (1999) on certain aspects of the sale of consumer goods and associated guarantees. OJ L 171, 7.7.1999 (p. 12–16)

Acknowledgements

I kindly thank Live Standal Bøyum for contributing to the collection and preparation of the data used in this article. Bøyum contributed to the initial analyses of the data from the open public consultation, categorizing and constructing variables, and to the organization and the implementation of the stakeholder interviews. I also thank Lisbet Berg, the research group “consumption policy and economy” at Oslo Metropolitan University, Sebastian Nessel and two anonymous reviewers for comments to earlier versions of this article. Finally, I wish to thank the national stakeholders interviewed for sharing their valuable time, knowledge and reflections.

Funding

Open Access funding provided by OsloMet - Oslo Metropolitan University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note