Abstract

This study explores a case of coaching deployed in experiential, interdisciplinary, and project-based courses. This study follows coaching in two courses that operated on a high-impact practice framework. In these courses, coaching was experienced by both students and faculty as a critical feature of the success of the courses. Students showed that coaching impacted their sense of the gravity of course content, their ownership of student-designed work, their relationships with faculty, and their experience of place-based learning. Faculty indicated that the coaching promoted transdisciplinary course planning, while their teaching benefited student engagement. We recommend practices for coaching that can support gains for students and faculty in experiential, project-based, interdisciplinary courses.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Transformative undergraduate student learning experiences are important to and expected by students attending campus-based education (Mayhew et al., 2016). It’s a fair expectation given the investments students and taxpayers make. At the same time, there are constraints on the undergraduate classroom as traditionally understood, based on financial models for teaching that drive decisions about faculty time, class size, and by extension, pedagogy. The culture of research institutions puts focus on discovery but reward structures do not always support or lead to better teaching (Kezar & Maxey, 2016; Lattuca & Stark, 2009). There are faculty who see this scenario and desire—and sometimes seek out—an opportunity to tinker and experiment with novel approaches. While teaching has been on the agenda of pedagogical scholars interested in redesign, changing teaching practice from the status quo requires new investments (O’Meara et al., 2015). Teaching for transformation requires deep dedication and additional professional learning time in order to help faculty educate students in ways that create meaningful impacts (Schneider, 2015).

The Spartan Studios project at MSU’s Hub for Innovation in Learning and Technology aims to facilitate transformative student learning in experiential, project-based, interdisciplinary learning while directly supporting faculty teams as they themselves learn by doing while teaching in novel, complex pedagogical models (Lattuca & Stark, 2009). In practice, Spartan Studios offered support to faculty willing to expand their own teaching experience. Studios offered a coached experience with guidance for syllabus design, anticipating learning outcomes, working across interdisciplinary teams, and guiding reflective prompts. Spartan Studios coaches aimed to lower the time to effective student transformation by embedding in courses and supporting faculty and students. This is a case of using coaching grounded in an evidence-based teaching framework. The coaching built on principles of experiential, interdisciplinary, and project-based learning during implementation which lead to nuanced learning outcomes for students and interesting changes for faculty participants.

Conceptual Framework

In this project, coaches supported instructors from two courses in applying a conceptual framework to guide course design, implementation, and assessment. The GORP framework (Gravity, Ownership, Relationship, and Place) (Heinrich et al., 2020), provides a theory of change (e.g. Mayne, 2015) to help instructors arrange and implement several known high-impact educational practices (HIPs) (Kuh, 2009). Using multiple HIPs in a semester-long course requires extra time and a fair amount of complexity in planning and execution. GORP was deployed as a heuristic to guide faculty to engage in complex teaching, receive coaching, and assess student learning. To apply the conceptual framework of GORP, the coaches followed a project implementation pattern loosely modeled on Agile project management (Pope-Ruark, 2012). In previous instances of using the GORP framework (described in the next section) students and instructors described transformational outcomes (Heinrich et al., 2020), so the coaches decided to continue such a pattern and explore the impact of dedicated coaching.

Gravity

Gravity refers to the idea in the course that has the largest pull on a learning experience in a classroom. Gravity focuses the energy of the course on something bigger than the course itself, contextualizing effort in the course in the service of a greater good. If the gravity comes from the intrinsic need of a larger project with impacts on people’s lives, grades become potentially less important than the success of the project. However, if the gravity is a grade, then a traditional outcomes-based approach by students and instructors is likely. In these classes, instructors decenter outcomes-based assessment and instructional techniques in favor of a flexible project-based experience of learning. Emergent outcomes are likely and planned reflection cycles help students and instructors document both intended and emergent learning.

Ownership

Ownership refers to the onus of control for learning. By the end of college, we know students are responsible for their learning. However, along the way, when an instructor determines and teaches a set of outcomes, the onus of control for those outcomes is held by the instructor, given power dynamics in a classroom (Gutierrez, Rymes, & Larson, 1995). When students have more agency in choosing an outcome, or even a pathway to an outcome, the onus of control begins to shift. In Spartan Studios courses, students identify and execute plans so they begin to experience more ownership over their creative solutions. Instead of directing students to outcomes, instructors listen to student plans and respond with expert guidance. The project priority and gravity drives planning and student teams, in turn, design their own solutions to the shared problem. In iterative steps, teams then develop delivery and accountability patterns. Individuals and teams see their contributions as their own, rather than something that an instructor preordained.

Relationships and Roles

Relationships in the course (e.g. teams, work groups, discipline groups, teacher/learner dyads, etc.) guided social and pedagogical structures including project-based experiential learning, teams for collaboration, and the trust between students and teachers necessary for the planned structures to operate. Through the process of identifying dominant communication patterns known as scripts and their alternatives, known as counterscripts (Gutierrez et al., 1995), relationships emerge that are collaborative among students with different skills and instructors with expertise to guide and inform students. The instructors develop approaches to guide, rather than direct (aka new scripts). Students assume the responsibility of production of solutions while instructors take responsibility for guidance and accountability.

Place and Space

The location in which the courses were offered, a flexible design space, emerged for many students as an important component in learning in this course. Place and space here are described as a both physical and conceptual resource. In the flexible classroom space, students design and re-configure the physical studio to meet the needs of their own teams as a means to express cognitive flexibility to execute a complex project. As students influence their immediate classroom space, they also experience place-based learning through community settings and field trips. By exerting influence over one space, students learn to exert influence on the priorities of the place and space of a project.

Research Questions

With an established interest in and framework for transformative student experiences, this descriptive case study explores the influence of professional coaching on instructors’ use of the GORP framework in Spartan Studios. Because the GORP framework was adopted by instructors in both courses in this case, we use the framework to frame and organize our analysis of the following questions:

-

1.

How does coaching support complex learning experiences in higher education?

-

A.

Which activities in the case helped to create powerful experiences, not all necessarily positive, for both students and faculty?

-

B.

In what ways do instructors experience growth (or not) through teaching in this model?

-

A.

Case Description

Faculty members partnered with a course and project coach from the Hub for Innovation in Learning and Technology at MSU to design, plan, and implement experiential, project-based, interdisciplinary courses. The courses were designed around the challenges of food waste (known hereafter as “Food Waste”) and of raising awareness of a campus wildlife sanctuary (“Sanctuary”). Here are a few terms we use for the roles in the case:

Instructors taught the course and were members of their respective departments who took on this teaching as overload. Coaches were scholar practitioners, employed by the MSU Hub, who supported the instructors. Students were enrolled members of the two courses described in this case. These students were not engaged in course support roles (e.g. learning assistant).

Planning (Fall 2018)

The main coach began working with faculty members to plan, develop, and recruit students for the two prototype courses. The main coach and Food Waste faculty members (one from the sciences, the other from the humanities) engaged advisors to recruit across the university. The main coach consulted with the instructors to develop their syllabi, and specifically encouraged faculty to conceptualize and increase interdisciplinarity using the GORP framework and Harden’s ladder of integration (Harden, 2000) as guidance. This coach also facilitated course logistics in the Hub’s flexible teaching space and acted as a participant observer during course sessions. The secondary coach consulted on the GORP framework. This secondary coach periodically met with faculty and the main coach to discuss GORP and advise the main coach. The Food Waste course’s syllabus took advantage of specific opportunities for interdisciplinarity and integration of course content and methods. The course faced, and met, a cross-disciplinary challenge of getting the courses cross-listed so they would meet two of MSU’s general education requirements. It was the first-ever course in MSU history to fulfill both biological science and humanities general education requirements. The coaches understood the dual general education role of this course to be high stakes and discussed the potential for a failure to reflect badly on the teaching faculty or the Studios project.

The main coach and instructor for the Sanctuary course attempted to recruit co-instructors, but the short lead time and constraints on teaching assignments contributed to this being a solo-taught course. The main coach encouraged connections to faculty members in other disciplines (what we called a “guest speaker plus” system) during the course. Sanctuary ran as a special topics upper-level course in a life sciences department. By the registration deadline, the Food Waste course had seven enrolled students and Sanctuary had 14. No administrative practices were in place in any of the instructors’ academic departments to divide or share credit for the teaching load or tuition revenue.

Launch (Spring 2019)

Using the GORP framework, the Studios courses deployed both didactic and active learning in conjunction with project-based learning and reflection. The courses delivered content knowledge followed by applied projects broken up into iterative production weeks, known as sprints, and reflections on each sprint. The two courses ran twice weekly in the Spring 2019 term (15 weeks). The structure of the courses (Table 1) followed the previously developed model (Heinrich et al., 2020).

The Sanctuary course’s burn-in period featured guest speakers from a variety of disciplines (wildlife conservation, campus art and architecture, outreach, science-art) and introduced the students to the sanctuary’s donor family. The Food Waste course included a burn-in period and team formation, followed by dividing the semester into design and planning phases for 3 student-led events in conjunction with the local library. Each course culminated in final presentations with a public audience. In the practice of Agile project management (Pope-Ruark, 2012), the faculty and coach began a pattern of weekly scrum meetings for planning, reflection, and logistics discussions.

Review of Relevant Literature

Studios courses are based on several interlocking frameworks and theories: experiential learning, project-based learning, and interdisciplinary learning. Planning to integrate assets from each approach while balancing out drawbacks and accounting for complexity is challenging for one or more instructors.

Challenges in Experiential Education

Experiential learning is a robust theoretical approach building on John Dewey’s (1938) assertion that the combination of experience plus reflection leads to learning. There are many extensions and variations on this idea, deployed across learning traditions to lead learners to various outcomes (Engeström & Sannino, 2012). Experiential learning is not limited to a single pedagogical tradition, yet the perceived simplicity of experiential learning (activity + reflection = learning) is also a challenge (Heinrich & Green, 2020). Complexity in designing, implementing, and assessing experiential education is a key factor in why many teachers in higher education do not use experiential learning effectively (Heinrich & Green, 2020). In light of the known structural and organizational barriers to effective teaching in research universities (O’Meara et al., 2015), temporally sensitive solutions that engage faculty and student development are essential to finding a strong place for renewed relevance of teaching in research extensive universities (Lowman, 2010). When deployed in repeating sequences, such as sprints, to leverage reflection, experiential learning can often lead to metalearning, and eventual transformation (Moon, 2013).

High Impact Practices (HIPs)

HIPs, applied in Spartan Studios, are incredibly important in helping undergraduate students achieve their college goals (Kuh, 2008) because students gain important skills and experiences that support and encourage lifelong learning. For known HIPs (Kuh, 2008, 2009) Tukibayeva and Gonyea (2014) provided additional explanation about why these six features are consequential for students, summarized here. High impact practices...

-

1.

Include a substantial amount of time and effort directed toward a challenging educational goal

-

2.

Involve shared intellectual experiences with faculty and peers

-

3.

Have interactions with others who have shared interests

-

4.

Have students exposed to a diversity of novel ideas, worldviews, and practices

-

5.

Provide students with frequent and continuous feedback about their performance

-

6.

See students applying what they learn in the classroom in different settings, experiencing firsthand how to approach real-world problems and situations

These characteristics are known as “engagement indicators” that can inform instructional designs and behaviors that drive the positive outcomes (National Survey of Student Engagement (NSSE), 2019). A key limitation of HIPs is that they are only impactful for students who experience them during educational experiences (Nelson Laird, 2017). Further, while HIPs are known to be more effective when students experience more than one, access to HIPs is differential for many reasons, especially among underserved students in higher education (Finley & McNair, 2013). To meet the demands of students for enriching experiences, it is up to instructors to learn how to teach with these tools to advance the knowledge and skills of students and up to organizations to help instructors who want to learn how to teach with HIPs.

Approaches to Coaching

Coaching is a good solution to the challenges of professional learning for teachers. Coaching is already known for benefits in many sectors, particularly sports, leadership, and business (Cummings & Worley, 2009; Fletcher, 2012; Theeboom et al., 2014) and research by experts of the business context of coaching has been produced for educators (Brockbank & McGill, 2006). Coaching in teaching is generally limited (in use and acceptance) by a lack of empirical research about the efficacy of coaching (Desimone & Pak, 2017) although applications of coaching in medical education are increasing (Deiorio et al., 2016; Sargeant et al., 2015). However, predictive elements of successful coaching are known and can be leveraged. Desimone and Pak outline five elements of coaching that are known to work well: content focus, active learning, coherence, sustained duration, and collective participation (Desimone, 2009, p. 4–5). Echoing these five elements is a recognition that coaching models should be based on “a focus on enabling students’ learning and reflective practice by educators” (Fletcher, 2012, p. 38).

Although the benefits of coaching are generally supported by the literature, well-known drawbacks include the time and energy required for effective and ongoing coaching and interpersonal issues within the coaching relationship (Ehrich & Hansford, 1999). Indeed, there have been warnings of a “darker side” of coaching and mentoring involving interpersonal issues and organizational culture (Long, 1997). Coaching research is increasing, but enthusiasm for its transformative potential for education is accompanied by warnings that coaching is no panacea:

[C]oaching is neither a quick fix nor a cheaper, shorter-term version of mentoring [...] there is a need for research to provide us with an evidence base from which better practice, that promotes learning by students and educators, can evolve” (Fletcher, 2012, p. 38).

In other words, evidence-driven approaches are necessary to build and spread effective coaching practices in higher education. The Spartan Studios approach was similar to instructional coaching (Desimone & Pak, 2017) rather than peer coaching (Huston & Weaver, 2008). But neither description fits perfectly. The coaching model we used leveraged experts in experiential learning and science communication to embed, observe, and give feedback, specifically about particular process-oriented approaches to teaching.

Methods

We applied a descriptive case study approach to highlight and examine the ways in which a coaching framework was offered and experienced in courses. Case studies are one type of qualitative research design that enables the researcher to conduct an in-depth analysis by collecting data through observing, documenting, and analyzing a specific activity or event (Creswell, 2013; Merriam, 2009). The key determinant that separates case study from other types of qualitative inquiry is its “time and activity boundaries” (Creswell, 2013, p. 14) in which the researcher “investigates a contemporary phenomenon and context” (Yin, 2009, p. 18). Furthermore, Merriam states that “for it to be a case study, one particular program (a bounded system), selected because it is typical, unique, experimental, or highly successful, etc., would be the unit of analysis” (Merriam, 2002, p. 8). In this case, the students and faculty experiences of coaching were the units of analysis while the two courses were the case boundaries. The course boundaries were of particular importance, because courses allowed us to focus on a specific setting where coaching could be examined (Stake, 2000). This case took place in the context of several MSU academic departments’ ethos and expectations of teaching, relevant literature on high impact practices, and emerging uses of program coaches in course settings. The descriptive approach to case study allowed analysis of behaviors and the resultant learning opportunities.

Researcher Positionality and Reflexivity

Reflexivity is considered a critical component of qualitative research design, particularly as it relates to the trustworthiness of one’s positionality to the body of work (Corlett & Mavin, 2018; Hardy et al., 2001). In this study, the first two authors identify as key design and implementation personnel on the course coaching project, and are (respectively) scholars of education and science communication. The second two authors were undergraduate zoology students with a deep interest in similar interdisciplinary, project-based, experiential learning environments and worked as research assistants during the coding and analysis phases. Neither of those authors was enrolled in either of the two courses in this case study. By acting as participant observers, we are “re-presenting” our own experiences as stewards of and stakeholders in the implementation of these courses (Cousin, 2010). By explicitly naming our mutual interest in the project’s success, we are practicing reflexivity and aim to be cognizant of the impact we bring as scholar practitioners.

Data Collection and Analysis

Myriad artifacts were examined for this case, including coach observations, 61 student reflections, other pieces of assigned student work, artifacts from student presentations, two post-course faculty interviews, and dozens of photographs. This study, including classroom observations, has been determined to be exempt under 45 CFR 46.104(d) 1 by the IRB at MSU.

The main coach made observations during classroom periods of students, faculty, and community guests within the learning space. The embedded approach yielded observations of student team choices or faculty coaching behavior, particularly with regard to patterns of intervention and of support or criticism of student work. During the project’s analysis phase, these observations were evaluated as one component of evidence.

Data analysis proceeded with the research team (all authors) conducting iterative data coding, using Dedoose qualitative analysis software. After software training and initial discussion of the research project, coding began with developing intercoder agreement. Two coders on the research team each coded 20 student reflections (40 total artifacts) using the GORP conceptual frames for the project. The research team discussed initial meanings and interpretations to develop understanding of each idea. Next, each coder reviewed the other coder’s work, and added parent and child codes. The research team then discussed progress and agreed that the coders were looking at the data in similar ways sufficient to code the bulk of the reflection data (N=61 written artifacts). The research team followed a similar agreement process when coding participant observations and interviews. Working together, the team agreed that codes were applied consistently by the two coders yielding intercoder agreement. Names of and identifying information about participants were removed from texts and pseudonyms were used to mask identities.

Results

We present data from three sources—faculty interviews, student writing and artifacts, and participant observations—that speak to the ways coaching mattered to the depth of learning for both students and faculty. Some instances during the courses were so salient that participants from all three groups wrote or reported on those learning moments from different points of view. Such results serve to help locate the importance and impact, positive or negative, of a particular event in a course.

Gravity and Coaching

Coaching influenced the ways students and faculty engaged with the concept of Gravity, the most important concept in the course. The initial coaching and planning meetings helped faculty develop engaging approaches to the content of Food Waste by connecting food waste to the broader issue of climate change.

The number one thing an individual can do for climate change is address food waste[...]expanding their tunnel vision [from] oh this is a problem [to] this is a big problem (Instructor J.R.)

In the Sanctuary class, both students and the instructor noticed how ideas, audiences, and community-wide purpose led to deeper meaning from the class.

Students...got to share their ideas with people outside of the room, I think it was all the more meaningful to see how outsiders [responded], and get feedback on their work and connect it with the overall meaning of the class. (Instructor Y.F.)

Overall, my teammates and I have connected with professors, visitors, and classmates in order to develop a deeper meaning in our project. Due to all these connections and relationships, our work has been shaped to become a greatly developed piece that holds meaning to a large group of people. (Sanctuary student Odessa)

Emotions generated by the interactions in the Sanctuary class also led students to notice the importance of the material and projects: “I feel I have come to understand the emotional weight of the Sanctuary in a way I did not understand before” (Sanctuary student Monique).

Ownership and Coaching

Coaching informed Ownership of learning and project success for students who were encouraged to ask for advice, and required to check in with faculty periodically, but needed to accomplish goals between reports. This student learned to trust teammates by letting go of control and allowing for collaboration.

While it started as my own idea, once we were collaborating on it, I stopped having as much control over it and it shifted to something the group owned, rather than just being mine. From the viewpoint of wanting the best possible product, collaboration is undoubtedly beneficial, and I’m glad the idea has developed into something more polished. (Sanctuary student Alena)

Faculty noticed variation between different groups’ performance and appreciated the ability of groups to self-manage. In turn, faculty had to trust students to work out problems and deliver novel solutions on time.

Two groups worked well and were self motivated, although...one had a difficult member, but they figured a way to work around that, they never came to me with that concern. (Sanctuary instructor Y.F.)

A faculty member in the Food Waste course noticed how students adopted different problem solving approaches after getting to know their group members (who are all in different majors).

[Students] came in thinking the problem is very displaced. By the end of two weeks, they recognize there are places they can intervene, there are direct choices they can make, that people individually can have an impact. (Food Waste instructor G.B.)

Students saw possibilities early in the project where they might be able to contribute within their teams, and describe empowerment with regard to their team-directed work. One student offered: “I do feel empowered and giddy with ideas, it widens my view on food waste and environmental science” (Food Waste student Cora).

The local library was the course’s community partner and the site of the prototype digester. During a visit to the library, an interaction with the liaison librarian produced a moment of recognition of ownership.

Student to Librarian: “I had a question about your digester”

Instructor J.R.: “It’s not HER digester, it’s (gestures to class) YOUR digester”

Several students looked stunned and excited, one exclaimed “OUR DIGESTER??!” (Coach notes).

This moment sparked students’ awareness of their ownership of the operation of the digester, which they demonstrated in the first community event at the library. Faculty wanted students to take ownership, knowing its value to learning, and created conditions and structures to make ownership a possibility.

Relationships, Roles, and Coaching

Coaching supported Relationships and Roles through faculty listening and offering feedback to students. These faculty conscientiously relinquished the role of knower and took on the mantle of following student curiosity with their respective expertise. One faculty member referring to a conversation with students early in the term: “We have plans but we’d like to hear what you want to do” (Food Waste instructor G.B.). By teaching with coaching, faculty sometimes let go of traditional power roles, and students noticed such emergent opportunities.

It gives me [an] opportunity to think in a new perspective. Students are the planners and creators. We are making impact[s on] others and we are having discussions. This class encourages us to be fully dependent on ourselves and be involved in everything. (Food Waste student Marisol)

Students also noticed when faculty shifted approaches. In the Food Waste course, faculty identified an on-campus opportunity for students to share their work and assigned it as an additional presentation, beyond what the students had planned for in their project sprints. From the coach observations: “[Faculty] telling students about [new event]. A little skepticism, students didn’t know about this.” The coach also noted

‘Puts a little urgency on the presentation, but an opportunity for another event with a student audience.’ [quoting instructor]. Very low enthusiasm [...] [faculty] telling them that this is happening and trying to convince them that they should be excited.

This was a moment of heightened tension in the course, in part because it was experienced as a sudden shift in roles away from student-driven decisionmaking. In a post-course interview, faculty members defended their decision to add the event, with one saying “...Students needed to recognize the opportunity in front of them” (Food Waste instructor J.R.).

Almost every student in the Food Waste class reflected on the extra event in some way. In response to a reflection question about any possible improvements to the course, this student referred to the unplanned nature of the extra event:

I would probably just ask for assignments in advance a little more even though I know it’s hard since this is the first cycle of this class. I juggle a lot during the semester and I like to plan my schedule a bit” (Food Waste student Elise).

Food Waste student Adeya said

I think starting the events earlier in the semester to allow for more time to plan and create. The second and third [extra] event felt rushed, but we still managed to create meaningful and structured events.

In retrospect, the extra event was considered by both faculty and students as having been worthwhile, but reflective data about the moment reveal the complex dynamics of faculty authority, trust, and relationships. We expand on these dynamics in the discussion section.

Overall, students took on more responsibility in this course model, with coaching roles helping to reinforce trust between students and faculty as co-contributors, and flatten the hierarchy in comparison to a more traditional course.

This set-up has given me confidence to validate my interpretation of various assignment mediums; with professors engaging with our class in discussion, it is encouraging to feel as though the student has ideas that are valid. (Food Waste student Ophelia)

Relationships between students and faculty can take many forms, but for students to express as much confidence and ownership in their work is indicative of a deeper connection to the topic made whole by the opportunity to genuinely shape the outcomes.

Place, Space, and Coaching

Coaching leveraged Place and Space by leveraging different learning environments and adapting with new kinds of teaching. The Sanctuary course visited the physical bird sanctuary three times in the semester. The faculty member noted some challenges with the visits.

It was a challenge, winter course is not the best time...early February was extremely cold, you get to a point where you shouldn’t be outside because it’s minus 25 [Faherenheit] and you can’t see all that much...the students doing a scavenger hunt...their cameras would stop working [due to the cold]. (Sanctuary instructor Y.F.)

The cold day was the first of three scavenger hunts, which were compelling enough to encourage critical thinking and reflection. The Sanctuary faculty member noted: “...Spring. It was very early spring, so a little bit before things were really happening (e.g. plants, flowers) out there, they had to go find “spring.” [Students] really liked the scavenger hunt.” A similar thread is reflected in the coach’s observations of students’ excitement about the scavenger hunt assignment, as well as using this visit to the space to inform their team-directed prototyping: “Open ended, they’re excited about it. Teams using the forest for affordances it brings to their project” (Coach notes).

Space and place can often help students carry their thinking outside of the classroom. A student wrote about how they noticed the impacts of space on their learning:

I’ve found that the novelty of having a “nontraditional” classroom space has really helped to engage me during class, and I believe that as a result I have been reflecting on the course content outside of class more than conventional, lecture based, classes. The HUB’s unique resources (ex. White boards, movable tables) have also seemed to foster more innovation and collaboration within student groups than I’ve typically experienced. (Sanctuary student Madison)

The coach noticed the difference that learning spaces made to the Food Waste course, which began in a traditional classroom and transitioned to the flexible learning space:

I’m noticing how much more relaxed and engaged the students are in the flex space. They chime in with their own experiences. Body language is more relaxed sitting at group tables compared to a narrow board-style room, one long table, that room felt rigid. (Coach notes)

Finally, both courses invited important guest and community partner views into their discussions both early on and for final presentations, rendering their typically limited, semi-private learning space as a communal place for orientation and reflection on a complex problem. Food Waste student Cora said: “I think all of the spaces have been important, they show us what our impact can look like and how the community interacts with the work of others.” When leveraged these ways, space and place can complement the gravity, ownership, and roles within a course.

Faculty Learning

Finally, coaching mattered to how faculty learned in these courses. For the Sanctuary course faculty, using sprints was new and required some scaffolding for planning design sprints and evaluation of project-based learning. “[I] provided structure and scaffolding to students and I feel like the Hub provided support for me” (Sanctuary instructor Y.F.). Food Waste instructor G.B. noted: “The scrums in particular made me focus on the positive, made me recognize where the great moments were, and to celebrate those.” Coaching is also tactical. The course coach planning in scrum supported faculty teaching. The course coach anticipated key pivots and reflections, helping to make sense of the patterns and experiences around the next corner:

I'm learning, but now having gone through it...we're going to revise the syllabus. I think we would have done it anyway, the recap of the week, but we had that ebb and flow of discussing what went well, having the structure at the Hub forced that interaction to challenge me to say 'what could we have done better?’ in the class. (Food Waste instructor J.R.)

Faculty reported that coaching and the kind of support they felt for trying new teaching approaches helped them be better teachers and that coaching this way could create a rationale for others to do the same. In effect, coaching leading to positive classroom experiences may serve as the gravity for instructors in seeking a passion for teaching.

Discussion

Fletcher (2012) invites us to provide “evidence [for coaching] from which better practice, that promotes learning by students and educators, can evolve” (p. 38). Results from this case show how coaching positively impacted outcomes for students, positively impacted outcomes for instructors, and created new discussions about scaling powerful experiential learning on a large university campus. Even moments of significant tension contribute to our understanding of and appreciation for the challenge represented by interdisciplinary, experiential, student-led learning experiences.

Trust and Faculty/Student Roles

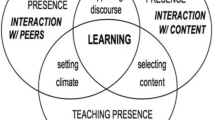

Within effective pedagogy (Gutierrez et al., 1995) and educational coaching, “establishment of trust is paramount” (Lofthouse et al., 2010, p. 10). Students need to trust faculty to empower them, faculty learn to trust the coach, and students trust each other to do the work entrusted to them. Coaches need to foster trusting relationships between coach and faculty while faculty need to foster trust in students learning to do good work. Higher-education coaching models in the literature oscillate between examining the benefits of faculty coaching their peers (Huston & Weaver, 2008) and models for faculty to act as coaches (rather than lecturers or advisors) to professional students (Sargeant et al., 2015). This case study shows results from a third way where scholar practitioners use a model to guide faculty in course planning, teaching, and assessment where that model encourages faculty to coach students through project-based, interdisciplinary learning experiences (Fig. 1).

Trust in the experiential classroom. The arrows represent directional trust developing both within and between groups of students and faculty members, as well as between the faculty and main coach. The dotted line represents the more indirect/logistical trust between this coach and the students. The coach handled equipment and space requests for the students but did not coach them in their project work; the coach also trusted that the students would act responsibly within the space

We found coaching this way to be co-constitutive. Because a coach was present during planning and launch, trust between coach and instructor was established to sufficiently inform teaching practice on a weekly basis. In turn, weekly reflections by instructors and written reflections by students served to inform coaching. We observed evidence of the effects of coaching among students and instructors. For example, the productivity of weekly course-planning scrums led to faculty starting to use scrums within the courses for post-event reflections. Students and faculty effectively established nested reflection practices that made reflection a regular part of course experience for everyone; such reflection has been described as a benefit of coaching practice (Huston & Weaver, 2008). In these ways, courses became sites of reflexive and transdisciplinary knowledge production (Gibbons et al., 2010; Harden, 2000) where nonexperts (students and community members) develop a sense of trust to participate in problem-solving processes.

Instructor and student reflections and coach observations also included examples of coursework that could be considered normal, too. Attendance and performance issues, disengagement, distractions in the learning environment, and students occasionally coming to class underprepared all occasionally materialized in the data. These regular kinds of interactions in the classroom serve to ground the seeming powerful learning experiences. We also noticed moments where diminished gravity eroded student ownership of and engagement in their projects; for example, one team realized that their artifact would not be erected on campus in the short term due to regulations about permanent structures. Despite their initial high levels of excitement, and several deliberate interventions by the instructor, their prototype did not vary very much between the second and third feedback sessions with campus members, and the main coach discovered their prototype in a garbage can at the end of the final presentation day. The above challenges found in traditional classrooms, as well as those related to sustaining engagement in these student-driven courses, did not detract from the importance of the topic of each course and the overall deep student engagement in the topics.

Experiential learning requires reflection that is analytical and rigorous, carefully guided for critical thinking, used to showcase reasoning, and shows how one thinks and relates to course content (Ash, Clayton, & Moses, 2009). The intent of reflection based on experiential learning opportunities is to offer opportunities for learners to consider their experience and convert it into transferrable learning which can be applied in new contexts (Kolb, 2014). Reflective practice by faculty members led to pivots in the courses. Faculty took initiative based on reflections and were constantly self-aware while tinkering, which aligns with effective coaching practice. Through the lens of the GORP model, faculty could reflect on how actions created or inhibited student ownership of their own learning. Further, coaching helped instructors spend time on conceptualizations of experiential learning during the planning process and via weekly coaching sessions. We observed that Studios courses offered both faculty development opportunities and potentially transformative outcomes for students, which can be positive components of higher education’s response to systemic changes (Kezar & Maxey, 2016).

Tensions and Growth

The course coaches noticed and shared with faculty members when we observed moments of classroom tension. Such moments involved the interplay between roles/relationship and ownership. Peter Senge writes about holding tension as a practice of systems thinking and developing mastery to engage learners in productive tensions, without prescribing a given outcome, thereby allowing for deeper buy-in and personal ownership of a topic (Senge, 2006). The interplay of roles in the course system was highlighted when the Food Waste faculty announced that the students had the opportunity to organize an extra event. The students—who had experienced autonomy as they scoped, planned, pitched, and had 3 events approved by faculty—were not excited about the new requirement for an extra event. The lack of initial excitement, in turn, disappointed the faculty members, who expected enthusiasm at this emergent opportunity, and insisted that the event was going to take place. The faculty saw the additional event as an opportunity for the class to practice their upcoming presentation for external stakeholders in front of a friendly campus audience, and to generate excitement on campus about this prototype course. From the students’ point of view, though, work to prepare for this event was rushed. Even though both students and faculty members felt in retrospect that the event went positively, and faculty remarked that it was the correct choice for the course, the announcement itself was a departure from student autonomy and was an assertion of faculty’s authority in the classroom. In this moment of tension, faculty lowered student autonomy needed for students to feel ownership in favor of their own (faculty) perspective.

Throughout this study, trust emerged as a constitutive vehicle for the interaction between the elements of relationship and ownership. However, faculty-student relationships did not always yield trust or student ownership. Food Waste’s extra event was an example of how trust can break down in the presence of an otherwise interesting opportunity. In practice, the faculty decision to add an event shaped the rest of the experience; students told us so. As coaches learning from the experience, we ask: how do we hold the tension—between implicit-explicit faculty authority and student ownership—without trying to solve the tension? The course coaches were able to leverage the previously built trust and relationship to openly discuss the outcomes of the decision with the faculty, and reflect observations of students. We focus on this example above and in our results section to emphasize the fragility of the trust developed during experiential courses. Trust is not guaranteed, but is the result of ongoing practices that empower student ownership and autonomy.

Impacts and Limitations

We witnessed the following campus and local impacts following these courses. The Food Waste course’s campus and community events involved interactions with students, family members, and the local business community. These conversations have laid the groundwork for further initiatives around reducing food waste at MSU and future external partnerships. Students produced a social media feed that will be available to students in future iterations of the course. Several of the Sanctuary course’s projects have been or are planned to be implemented on campus or virtually, by departments or student clubs. Both courses were covered by press releases by MSU development offices. We hope to see expanded benefits to campus participants and our local communities in line with those observed by Wenger-Trayner and Wenger-Trayner (2019) in their study of the d.school’s University Innovation Fellows.

The Spartan Studios project has since expanded its design and scope based on the lessons from this case study, but who will take up the opportunity amid resource constraints and other institutional challenges? We are currently designing a campus-wide administrative framework to deliver more and more kinds of transformational teaching and learning experiences for participating MSU undergraduates and faculty. While we highlight the transformative outcomes, coaching is a lot of work that currently is not allocated. It will be challenging to offer faculty these opportunities without changes to the structures within which teaching is implemented on campus (O’Meara et al., 2015). Faculty teaching loads and funding models need to be developed to support faculty interested in trying new ways of teaching. Buy-in from department chairs, deans, and university administration is required; we recognize that “pedagogy and administration are indelibly intertwined” (McCarthy et al., 2018, p. 1549). We will need to develop a core team of faculty champions (Kezar & Maxey, 2016) who can continually network these ideas and articulate the benefits of experiential learning, transdisciplinarity, and student-owned projects for faculty. To help face these challenges, we have created intellectual partnerships with James Madison University’s X-Labs, written a faculty-facing playbook, and continued investigation on pedagogical models and teaching methods in multi-site research.

We acknowledge that this study has limitations. As a small-scale prototype, it involved only two courses with 21 total enrolled students and 3 faculty members at one institution. One of the courses was not co-taught and thus did not offer a fully interdisciplinary experience. In addition, the short planning cycle meant that students had to be actively recruited for these courses; the students may not be representative of students taking experiential courses in general. Another limitation is that the main coach was unable to observe all interactions between faculty members, within student teams, or between faculty and students. Relatedly, we did not analyze all classroom assignments or communications, as our focus was on using a large pool of data of deliberately distinct types to triangulate student reflection data, course observations, and faculty interviews. Lastly, as we discuss in the introduction, this study employed the GORP framework to inform intensive coaching throughout course design and implementation. As a result, this study did not compare experiential courses with and without the intervention of coaching, or compare experiential courses to more didactic courses.

We have learned that we need to create space for faculty to practice with new teaching methods yet also offer guidance about how we understand those methods to be more or less effective. There is a tension in this kind of coaching. Coaching went deeper than giving advice to better teach for experiential learning; we offered a loosely-structured process because it helped create reliably observable patterns of student classroom behavior that could be documented and assessed for student learning. Coaching, while labor intensive, yields a reflective pedagogy which guides students toward reflective learning. Sometimes instructors also demonstrated reflective learning outcomes.

Conclusion

Rather than try to create a perfect pedagogical event, Studios coaches—individuals trained in pedagogy, communication, and assessment—encouraged instructors to focus on student transformation and gave pedagogical direction to help. These coaching approaches emerged as a cohesive model that led us to new questions like: How are strong pedagogical models for transformative learning experiences for students the correct, high bar for higher education? Overall, the experience became a professional learning model for faculty participants. Course coaches were able to give feedback to faculty when and where they saw faculty growth; an important part of the developmental space. These faculty might, in turn, take these approaches forward with different courses in their future teaching portfolios. Along the way, course coaches saw critical and curious questions from faculty that demonstrated how they were thinking about teaching differently. Simultaneously, coaching facilitated the development of contact zones for social innovation in collaboration with industry, government, and community partners. Students benefited from rich learning experiences and real exposure to people and methods from new disciplines. Faculty benefited from learning new and effective pedagogical and assessment approaches, and better connecting scholarship with teaching. Coaching created the conditions of possibility for teaching and learning in distinct, transformative ways.

References

Ash, S. L., Clayton, P. H., & Moses, M. G. (2009). Learning through critical reflection: A tutorial for students in service-learning. Authors.

Brockbank, A., & McGill, I. (2006). Facilitating reflective learning through mentoring and coaching. KoganPage.

Corlett, S. & Mavin, S. (2018). Reflexivity and researcher positionality. In C. Cassell, A. L. Cunliffe, & G. Grandy (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of qualitative business and management research methods (pp 377–398). SAGE Publications.

Cousin, G. (2010). Positioning positionality: The reflexive turn. In M. Savin-Baden and C. Howell (Eds.), New approaches to qualitative research, wisdom and uncertainty (pp 9–18). Routledge Education.

Creswell, J. W. (2013). Qualitative inquiry & research design: Choosing among the five approaches. Sage Publications.

Cummings, T. G., & Worley, C. G. (2009). Organizational development and change. South-Western Cengage Learning.

Deiorio, N. M., Carney, P. A., Kahl, L. E., Bonura, E. M., & Juve, A. M. (2016). Coaching: A new model for academic and career achievement. Medical Education Online, 21(1), 33480. https://doi.org/10.3402/meo.v21.33480

Desimone, L. M. (2009). Improving impact studies of teachers’ professional development: Toward better conceptualizations and measures. Educational Researcher, 38(3), 181–199. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X08331140

Desimone, L. M., & Pak, K. (2017). Instructional coaching as high-quality professional development. Theory into Practice, 56(1), 3–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405841.2016.1241947

Dewey, J. (1938). Experience and education. Macmillan.

Ehrich, L. C., & Hansford, B. (1999). Mentoring: pros and cons for HRM. Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources, 37(3), 92–107.

Engeström, Y., & Sannino, A. (2012). Whatever happened to process theories of learning? Learning, Culture and Social Interaction, 1(1), 45–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lcsi.2012.03.002

Finley, A., & McNair, T. (2013). Assessing underserved students’ engagement in high-impact practices. AAC&U.

Fletcher, S. J. (2012). Coaching: An overview. In S. J. Fletcher and C.A. Mullen (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of mentoring and coaching in education (pp 24-40). SAGE Publications.

Gibbons, M., Limoges, C., Nowotny, H., Schwartzman, S., Scott, P., & Trow, M. (2010). The new production of knowledge: The dynamics of science and research in contemporary societies. SAGE Publications. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446221853

Gutierrez, K., Rymes, B., & Larson, J. (1995). Script, counterscript, and underlife in the classroom: James Brown versus Brown v. Board of Education. Harvard Educational Review, 65(3), 445–472. https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.65.3.r16146n25h4mh384

Harden, R. M. (2000) The integration ladder: A tool for curriculum planning and evaluation. Medical Education, 34(7), 551–557. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2923.2000.00697.x

Hardy, C., Phillips, N., & Clegg, S. (2001). Reflexivity in organization and management theory: A study of the production of the research ‘subject.’ Human Relations, 54(5), 531–560. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726701545001

Heinrich, W. F. & Green, P. M. (2020). Remixing approaches to experiential learning, design, and assessment. Journal of Experiential Education, 43(2), 205–223.

Heinrich, W. F., Lauren, B., & Logan, S. (2020). Interdisciplinary teaching, learning and power in an experiential classroom. Submitted to College Teaching, July 2020.

Huston, T., & Weaver, C. L. (2008). Peer coaching: Professional development for experienced faculty. Innovative Higher Education, 33, 5–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10755-007-9061-9

Kezar, A., & Maxey, D. (2016). Envisioning the faculty for the twenty-first century: Moving to a mission-oriented and learner-centered model. Rutgers University Press.

Kolb, D. A. (2014). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. Pearson FT Press.

Kuh, G. D. (2008). High-impact educational practices: What they are, who has access to them, and why they matter. AAC&U.

Kuh, G. D. (2009). What student affairs professionals need to know about student engagement. Journal of College Student Development, 50(6), 683–706. https://doi.org/10.1353/csd.0.0099

Lattuca, L. R., & Stark, J. S. (2009). Shaping the college curriculum: Academic plans in context (2nd ed.). Jossey-Bass.

Lofthouse, R., Leat, D., Towler, C., Hall, E. & Cummins, C. (2010). Improving coaching: Evolution not revolution. National College for Leadership in Schools and Children’s Services.

Long, J. (1997), The dark side of mentoring. Australian Educational Research, 24(2), 115–133.

Lowman, R. L. (2010). Leading the 21st-century college and university: Managing multiple missions and conflicts of interest in higher education. The Psychologist-Manager Journal, 13(4), 237–243. https://doi.org/10.1080/10887156.2010.522478

Mayhew, M. J., Rockenbach, A. N., Bowman, N. A., Seifert, T. A., & Wolniak, G. C. (2016). How college affects students: 21st century evidence that higher education works (Vol. 3). John Wiley & Sons.

Mayne, J. (2015). Useful theory of change models. Canadian Journal of Program Evaluation, 30(2), 119–142.

McCarthy, S., Barnes, A., Holland, S. K., Lewis, E., Ludwig, P., & Swayne, N. (2018). Making it: Institutionalizing collaborative innovation in public higher education. 4th International Conference on Higher Education Advances (HEAd’18), 1549–1557.

Merriam, S. B. (2002). Qualitative research in practice: Examples for discussion and analysis (1st ed.). Jossey-Bass.

Merriam, S. B. (2009). Qualitative case study research. In Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation (2nd ed., pp 39-54). Jossey-Bass.

Moon, J. A. (2013). Reflection in learning and professional development: Theory and practice. Routledge.

National Survey of Student Engagement (NSSE). (2019). Engagement indicators. http://nsse.indiana.edu/html/engagement_indicators.cfm. Accessed 11 December 2019.

Nelson Laird, T. F. (2017). Best practices for assessing HIPs: Understanding and using data to enhance student learning. Workshop, AAC&U HIPs Summer Institute.

O’Meara, K., Eatman, T., & Peterson, S. (2015). Advancing engaged scholarship in promotion and tenure: A roadmap and call for reform. Liberal Education, 101(3), 52–57.

Pope-Ruark, R. (2012). We scrum every day: Using scrum project management framework for group projects. College Teaching, 60(4), 164–169. https://doi.org/10.1080/87567555.2012.669425

Sargeant, J., Lockyer, J., Mann, K., Holmboe, E., Silver, I., & Armson, H. (2015). Facilitated reflective performance feedback: Developing an evidence- and theory-based model that builds relationship, explores reactions and content, and coaches for performance change (R2C2). Academic Medicine, 90(12), 1698–1706.

Schneider, C. G. (2015). The LEAP challenge: Transforming for students, essential for liberal education. Liberal Education, 101(1-2), 6–15.

Senge, P. M. (2006). The fifth discipline: The art & practice of the learning organization. Doubleday.

Stake, R. E. (2000). Case studies. In N. K. Denzin, & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (pp 435-453). SAGE Publications.

Theeboom, T., Beersma, B., & van Vianen, A. E. M. (2014). Does coaching work? A meta-analysis on the effects of coaching on individual level outcomes in an organizational context. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 9(1), 1-18, https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2013.837499

Tukibayeva, M., & Gonyea, R. M. (2014). High-impact practices and the first year student. New Directions for Institutional Research, 160(2), 19–35. https://doi.org/10.1002/ir.20059

Wenger-Trayner, B., & Wenger-Trayner, E. (2019). Designing for change: Using social learning to understand organizational transformation. Learning 4 A Small Planet.

Yin, R. (2009). Case study research: Design and methods (4th ed.). SAGE Publications.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to MSU’s Hub for Innovation in Learning and Technology for sponsoring these courses. Thanks to the faculty members and students who participated in this research. Thanks to the College of Arts and Letters and the College of Agriculture and Natural Resources for supporting these courses. This research benefited from ongoing consultation with James Madison University’s X-Labs, especially Nick Swayne, Erica Lewis, Patrice Ludwig, and Seán McCarthy. We sincerely thank two anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments.

Funding

This research was not supported by any external funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The study was conceived and designed by William Heinrich. Data collection was performed by Eleanor Louson and William Heinrich. Coding was performed by Caroline Blommel and Aalayna Green. Data analysis was performed by all authors. The first draft was written by William Heinrich and Eleanor Louson, and all authors edited and commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest. The first author of this manuscript changed employment after the manuscript was first submitted and prior to the revised manuscript being resubmitted. The authors affirm that revisions to the manuscript were based on reviewers’ suggestions and were unrelated to this change in employment.

Consent to Publish

All authors consent to publish this manuscript.

Code Availability

Authors are prepared to share codes used in the analysis phase of this research upon request.

Availability of Data and Material

Authors are prepared to send data or other relevant material upon request.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Heinrich, W.F., Louson, E., Blommel, C. et al. Who Coaches the Coaches? The Development of a Coaching Model for Experiential Learning. Innov High Educ 46, 357–375 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10755-020-09537-3

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10755-020-09537-3