Abstract

This paper studies the relation between the evolution of capital controls and electoral cycles. We exploit a dataset containing detailed information on the level of restrictions on capital flows for 98 countries on an annual basis from 1995 to 2015, constructed by Fernandez et al. (IMF Econ Rev 64:548–574, 2016). First, we find that restrictions are more likely to increase during an election year. The relationship between changes in capital controls and elections is more robust than with any other economic variable. Second, these changes are driven predominantly by restrictions on capital outflows and on relatively liquid asset categories. Third, changes occur mostly after elections, though not exclusively. Finally, capital controls increase more if the new government is more leftist or less liberal than its predecessor, and greater electoral uncertainty is related to higher restrictions on capital flows. Overall, these results suggest that theories examining the cyclical properties of capital controls should also consider electoral cycles.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

“Booms and busts in aggregate activity are associated with virtually no movements in capital controls,” Fernández et al. (2015, p. 1).

As explained by Chinn and Ito (2006), “it is almost impossible to distinguish between de jure and de facto controls on capital transactions.”

Our sample is restricted to countries included in this dataset. A full list of countries can be found in “Appendix 1.” All but three countries, namely Bangladesh (18 observations); Iran and Myanmar (19 observations, respectively), are observed for the entire sample period.

If the system of a country does not fit this classification, we focus on the general election.

Results without this transformation are qualitatively similar and are available in a previous version of this paper.

In addition to these tests, we also estimate Eq. (1) using the Chinn–Ito measure of capital openness. The sign of the election dummy is consistent with the results presented in this section. The relationship is, however, not significant. This might be explained by the construction of the Chinn–Ito index, as discussed in the previous section.

In addition, we also run the model after dropping 11 countries from our sample which did not hold elections between 1995 and 2015: the results are very similar to the baseline results and are displayed in Table 12.

Alternatively, we also run the model on a sample excluding countries that have ever experienced early elections. Results are displayed in Table 12. The magnitude and significance of the electoral dummy slightly decrease, but the conclusion is similar.

This result is robust to all specifications detailed in Sect. 3.1 on the main results.

Not all of the ten subcategories are available for all years, which is why the sample size varies in the ten specifications. For example, bonds are available only since 1997 (Fernández et al. 2016).

However, for some countries/years, the period under consideration goes beyond December 31, admittedly introducing additional noise.

A potential issue could be that after elections it typically takes time until governments are formed. For all elections in the sample, we collected the exact date of either the first parliamentary session in parliamentary systems or the president’s inauguration in presidential systems and repeated the analysis around the week of government formation. We do not find major changes compared to the analysis using the election date.

Cerutti et al. (2017) constructed a cross-country dataset at the quarterly level focusing on changes in intensity of various prudential tools, including reserve requirements on foreign currency-denominated accounts. We repeated the same analysis as with Forbes et al. (2015) and Pasricha et al. (2018) but do not observe evidence of electoral cycle when using this specific measure.

We drop observations from a sixth category that encompasses cases for which a proper classification is meaningless, for instance during a revolution or a civil war. Also, for some cases ideology is missing for the entire observation period (e.g., Bahrain, Myanmar, and Saudi Arabia).

The same pattern appears when we take into account only planned elections.

Available at https://manifesto-project.wzb.eu.

References

Aizenman, J., and G.K. Pasricha. 2013. Why do emerging markets liberalize capital outflow controls? fiscal versus net capital flow concerns. Journal of International Money and Finance 39: 28–64.

Alesina, A., V. Grilli, and G.M. Milesi-Ferrett. 1993. The political economy of capital controls. Technical Report. National Bureau of Economic Research.

Alfaro, L. 2004. Capital controls: A political economy approach. Review of International Economics 12: 571–590.

Arellano, M., and S. Bond. 1991. Some tests of specification for panel data: Monte carlo evidence and an application to employment equations. The Review of Economic Studies 58: 277–297.

Arellano, M., and O. Bover. 1995. Another look at the instrumental variable estimation of error-components models. Journal of Econometrics 68: 29–51.

Benigno, G., H. Chen, C. Otrok, A. Rebucci, and E.R. Young. 2016. Optimal capital controls and real exchange rate policies: A pecuniary externality perspective. Journal of Monetary Economics 84: 147–165.

Bernhard, W., and D. Leblang. 1999. Democratic institutions and exchange-rate commitments. International Organization 53: 71–97.

Bianchi, J., 2011. Overborrowing and systemic externalities in the business cycle. American Economic Review 101: 3400–3426.

Brender, A., and A. Drazen. 2005. Political budget cycles in new versus established democracies. Journal of Monetary Economics 52: 1271–1295.

Caselli, F., G. Esquivel, and F. Lefort. 1996. Reopening the convergence debate: A new look at cross-country growth empirics. Journal of Economic Growth 1: 363–389.

Cerutti, E., S. Claessens, and L. Laeven. 2017. The use and effectiveness of macroprudential policies: New evidence. Journal of Financial Stability 28: 203–224.

Chang, R. 2010. Elections, capital flows, and politico-economic equilibria. The American Economic Review 100: 1759–1777.

Chinn, M.D., and H. Ito. 2006. What matters for financial development? Capital controls, institutions, and interactions. Journal of Development Economics 81: 163–192.

De Luca, G., J.R. Magnus, et al., 2011. Bayesian model averaging and weighted-average least squares: Equivariance, stability, and numerical issues. Stata Journal 11: 518–544.

Durnev, A. 2010. The real effects of political uncertainty: Elections and investment sensitivity to stock prices. Working paper.

Eichengreen, B. 2001. Capital account liberalization: What do cross-country studies tell us? The World Bank Economic Review 15: 341–365.

Eichengreen, B., and A. Rose. 2014. Capital controls in the 21st century. Journal of International Money and Finance 48: 1–16.

Farhi, E., and I. Werning. 2014. Dilemma not trilemma? capital controls and exchange rates with volatile capital flows. IMF Economic Review 62: 569–605.

Fernández, A., A. Rebucci, and M. Uribe. 2015. Are capital controls countercyclical? Journal of Monetary Economics 76: 1–14.

Fernández, A., M.W. Klein, A. Rebucci, M. Schindler, and M. Uribe. 2016. Capital control measures: A new dataset. IMF Economic Review 64: 548–574.

Forbes, K., M. Fratzscher, and R. Straub. 2015. Capital-flow management measures: What are they good for? Journal of International Economics 96: S76–S97.

Fratzscher, M. 2012. Capital flows, push versus pull factors and the global financial crisis. Journal of International Economics 88: 341–356.

Grilli, V., and G.M. Milesi-Ferretti. 1995. Economic effects and structural determinants of capital controls. IMF Staff Papers 42: 517–551.

Halikiopoulou, D., K. Nanou, and S. Vasilopoulou. 2012. The paradox of nationalism: The common denominator of radical right and radical left euroscepticism. European Journal of Political Research 51: 504–539.

Ilzetzki, E., C.M. Reinhart, and K.S. Rogoff. 2017. Exchange Arrangements Entering the 21st Century: Which Anchor Will Hold?. Technical Report. National Bureau of Economic Research.

IMF. 2012. The liberalization and management of capital flows—an institutional view. Technical Report. International Monetary Fund.

Ito, T. 1990. The timing of elections and political business cycles in Japan. Journal of Asian Economics 1: 135–156.

Julio, B., and Y. Yook. 2012. Political uncertainty and corporate investment cycles. The Journal of Finance 67: 45–83.

Julio, B., and Y. Yook. 2016. Policy uncertainty, irreversibility, and cross-border flows of capital. Journal of International Economics 103: 13–26.

Korinek, A., and D. Sandri. 2016. Capital controls or macroprudential regulation? Journal of International Economics 99: S27–S42.

Kriesi, H., E. Grande, R. Lachat, M. Dolezal, S. Bornschier, and T. Frey. 2006. Globalization and the transformation of the national political space: Six european countries compared. European Journal of Political Research 45: 921–956.

Leblang, D.A. 1997. Domestic and systemic determinants of capital controls in the developed and developing world. International Studies Quarterly 41: 435–454.

Magnus, J.R., O. Powell, and P. Prüfer. 2010. A comparison of two model averaging techniques with an application to growth empirics. Journal of Econometrics 154: 139–153.

Merz, N., S. Regel, and J. Lewandowski. 2016. The manifesto corpus: A new resource for research on political parties and quantitative text analysis. Research and Politics 3: 2053168016643346.

Milesi-Ferretti, G.M. 1998. The political economy of capital controls. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Moral-Benito, E. 2015. Model averaging in economics: An overview. Journal of Economic Surveys 29: 46–75.

Oatley, T. 1999. How constraining is capital mobility? the partisan hypothesis in an open economy. American Journal of Political Science 43:1003–1027.

Pasricha, G. 2017. Policy rules for capital controls. Bank of Canada Staff Working Paper 2017-42.

Pasricha, G.K., M. Falagiarda, M. Bijsterbosch, and J. Aizenman. 2018. Domestic and multilateral effects of capital controls in emerging markets. Journal of International Economics 115: 48–58.

Quinn, D.P., and C. Inclan. 1997. The origins of financial openness: A study of current and capital account liberalization. American Journal of Political Science 41: 771–813.

Sachs, J., and C. Wyplosz. 1986. The economic consequences of president mitterrand. Economic Policy 1: 261–306.

Schindler, M. 2009. Measuring financial integration: A new data set. IMF Staff Papers 56: 222–238.

Shi, M., and J. Svensson. 2006. Political budget cycles: Do they differ across countries and why? Journal of Public Economics 90: 1367–1389.

Smith, A. 2004. Election timing. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Stiglitz, J.E., and J.A. Ocampo. 2008. Capital market liberalization and development. Oxford: University Press on Demand.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the coeditor, Emine Boz, as well as two anonymous reviewers for their useful and constructive comments. We would like to thank Konstantins Benkovskis, Monika Bütler, Tommy Krieger, Jan Mellert, Pierre-Guillaume Méon and participants at the European Public Choice Society Meeting, Rome, 2018, at the Baltic Economic Association meeting, Vilnius, 2018, at the Annual Congress of the Swiss Society for Economics and Statistics, St. Gallen, 2018, and at the workshop on Political Cycles, Rennes, 2018, for insightful comments and suggestions. We are also grateful to Kristin Forbes for sharing some data with us.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Names of Countries Included in Sample

Algeria | Guatemala | Paraguay |

Angola | Hungary | Peru |

Argentina | Iceland | Philippines |

Australia | India | Poland |

Austria | Indonesia | Portugal |

Bahrain | Iran. Islamic Rep. | Qatar |

Bangladesh | Ireland | Russian Federation |

Belgium | Israel | Saudi Arabia |

Bolivia | Italy | Singapore |

Brazil | Jamaica | Slovenia |

Brunei Darussalam | Japan | South Africa |

Bulgaria | Kazakhstan | Spain |

Burkina Faso | Kenya | Sri Lanka |

Canada | Korea. Rep. | Swaziland |

Chile | Kuwait | Sweden |

China | Kyrgyz Republic | Switzerland |

Colombia | Latvia | Tanzania |

Costa Rica | Lebanon | Thailand |

Cote d’Ivoire | Malaysia | Togo |

Cyprus | Malta | Tunisia |

Czech Republic | Mauritius | Turkey |

Denmark | Mexico | Uganda |

Dominican Republic | Moldova | Ukraine |

Ecuador | Morocco | United Arab Emirates |

Egypt. Arab Rep. | Myanmar | UK |

El Salvador | Netherlands | United States |

Ethiopia | New Zealand | Uruguay |

Finland | Nicaragua | Uzbekistan |

France | Nigeria | Venezuela. RB |

Georgia | Norway | Vietnam |

Germany | Oman | Yemen. Rep. |

Ghana | Pakistan | Zambia |

Greece | Panama |

Appendix 2: Data Sources

Variable | Source(s) | Detailed description |

|---|---|---|

Capital controls | Fernandez et al. (2016) | Annual measure of capital controls in the aggregates, on outflows, inflows and ten subcategories. Measured annually at the end of the year. For 100 countries between 1995 and 2015 |

Political system | DPI (2015) | Allocation into presidential and parliamentary system |

Dates of parl. elections | DPI (2015) | |

Dates of presidential elections | Various Internet sources | |

Early/planned elections | Various sources | Evidence whether elections took place at a date planned in advance or were held earlier |

Dates of changes in capital controls | Forbes et al. (2015) | Precise dates of events changing capital controls for a subsample of 36 countries between 2009 and 2011 |

Names of leaders and parties | Various Internet sources | |

Government ideology | DPI; various Internet sources | |

REER (% change) | World Bank | Change in real exchange rate |

Credit (% change) | World Bank | Change in domestic credit to private sector (% of GDP) |

FX (% change) | World Bank | Change in total reserves minus gold (current US$) to GDP |

Exchange regime | Ilzetzki et al. (2017) | Six categories: peg, crawling peg, managed float, free falling, free and dual market |

Fisc. Deficit (% GDP) | World Bank | Total government expenditure minus government revenue over GDP |

Curr. Account (% GDP) | World Bank | Trade balance plus net income and direct payments over GDP |

GDP per capita | World Bank | |

GDP growth | World Bank | |

Democracy | Polity4 | Index ranging from \(-10\) to 10. If the value is greater than or equal to zero, the country is classified as a democracy |

Openness | IMF | Trade openness defined as the sum of imports and exports over GDP |

Debt (% GDP) | World Bank | Total government debt to GDP |

Interest differential (% change) | World Bank | Change in domestic/USA interest rate differential |

Appendix 3: Complementary Regressions

See Tables 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14 and 15.

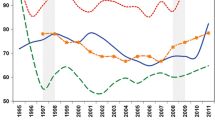

Capital controls on outflows increase more if election outcomes are uncertain—planned elections. Note Expected change in average capital controls on outflows conditional on electoral uncertainty. Electoral uncertainty is measured as the difference between the vote share of the two leading parties/candidates in the first election round. 90% confidence interval bands. Restricted to the subsample of democracies, and considering only planned elections