Abstract

The enfranchisement of foreigners is likely one of the most controversial frontiers of institutional change in developed democracies, which are experiencing an increasing number of non-citizen residents. We study the conditions under which citizens are willing to share power with non-citizens. To this end, we exploit the setting of the Swiss canton of Grisons, where municipalities are free to decide on the introduction of non-citizen voting rights at the local level (a so called opting-in regime). Consistent with the power dilution hypothesis, we find that enfranchisement is less likely when the share of resident foreigners is large. Moreover, municipalities with a large language/cultural minority are less likely to formally involve foreigners. In contrast, municipality mergers seem to act as an institutional catalyst, promoting democratic reforms. A supplementary panel analysis on electoral support for an opting-in regime in the canton of Zurich also backs the power dilution hypothesis, showing that a larger share of foreigners reduces support for an extension of voting rights.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Over the last decades, international migration and mobility have led to an increase in the proportion of non-citizen residents in many democratic countries. This development has reignited a long-standing discussion about the extent of non-citizens’ formal inclusion in the democratic process, the focus being on the right to vote as a fundamental participatory aspect of democracy. Thereby, primary normative questions refer to whether voting rights should be unbundled from the legal status of citizenship and under what conditions these rights should be granted. Proponents of non-citizen voting rights emphasize the procedural value of electoral participation rights and the democratic principle postulating that all the individuals (not just citizens) whose interests are affected by a state’s laws and policies should have a say about its rules.Footnote 1 A related argument puts forward the potential benefits for political integration, as foreigners are expected to be more motivated to engage in the political discourse and to identify more with the polity of their host country if they are granted formal participation rights. In contrast, opponents stress the loyalty and commitment associated with naturalization as preconditions for access to voting rights in order to maintain stable communities.Footnote 2 Overall, we can rely on an elaborate reasoning in favor of or against non-citizen political participation rights.Footnote 3 However, there is a relatively poor understanding of the conditions under which the formal political inclusion of non-citizens is actually possible and accepted by the resident citizens, i.e. under which they are willing to share power with non-citizens.

In this paper, we present a corresponding positive analysis on the conditions under which citizens are willing to grant voting rights to non-citizens and thus to support more inclusive democratic institutions.Footnote 4 We first derive and structure a set of hypotheses about the potential drivers of power sharing. We then exploit an ideal context to learn about their empirical relevance in democratization at the micro level and study the determinants of the introduction of non-citizen voting rights across a set of municipalities within the same country and state (canton). Citizens in these municipalities have the constitutional right but not the obligation (opting-in clause) to extend active and passive voting rights to non-citizens. Specifically, we undertake a quantitative case study for the Swiss canton of Grisons (German: Graubünden). After a complete revision of the cantonal constitution in 2004, 208 municipalities were given the right to independently introduce local voting rights for their non-citizen resident population. This setting is attractive compared to cross-country comparisons, as it involves a rather homogeneous set of jurisdictions facing similar economic and political conditions.

We supplement this cross-sectional analysis on the actual enfranchisement of foreigners at the municipal level with an analysis of the determinants of the electoral support for a constitutional amendment that would have granted the same right to municipalities in the canton of Zurich. Citizens in the canton of Zurich voted on the introduction of an opting-in clause twice, in 1993 and in 2013. While both initiatives were rejected at the ballot box, they still offer the opportunity to study how public support for non-citizen voting rights evolved over time. In particular, the panel structure allows us to statistically account for time-invariant unobserved characteristics of the municipalities and to study how changes in municipality characteristics over time are related to changes in the support for the opting-in regime.

We address two sets of hypotheses. A first set that concentrates on citizens’ instrumental interests and the institutional context and a second set that instead concentrates on preference-based motives. With regard to the former, we study whether non-citizen voting rights are less likely to be introduced in municipalities where they would dilute citizens’ political power more. Power dilution is expected to be more pronounced in smaller municipalities (as there the weight of an individual vote is reduced more with an additional voter than in a large municipality), in municipalities with an assembly (because control of the executive is direct and not via a parliament), and in municipalities with a higher share of foreigners (due to the simple effect on the size of the eligible electorate). Reluctance to share power may thereby be motivated by various reasons, a perceived cultural threat due to a difference in preferences between the insiders (citizens) and the outsider group (foreigners) being a particularly prominent one. Depending on the composition of the foreign population, power sharing is also expected to be less likely where citizens might be more concerned about a potential fiscal burden when foreigners obtain formal electoral rights. Moreover, in the context of municipal mergers, reflecting a broader window of opportunity for institutional change, previous power structures can be seen as up for negotiation; consequently, a suffrage extension is more likely to be expected. With regard to the preference-based hypotheses, we analyze whether the experience of a minority status within the canton due to language (Romansh, Italian) or history (Walser heritageFootnote 5) relates to the willingness to share power. In addition, we test hypotheses that refer to citizens’ partisan, immigration, and historical power-sharing preferences and their experience or contact with mobile seasonal workers (i.e. non-resident foreigners).

In the cross-sectional analysis for the canton of Grisons, we find that by 2017 about 30% of the original municipalities had adopted non-citizen voting rights. The Analysis documents hat the socio-demographic composition of the municipalities in terms of age structure, education, unemployment and income do not seem to be systematically related to the introductions of local voting rights for non-citizens. The same holds for the population size of the municipalities. However, a higher proportion of foreigners has a statistically significant negative correlation with the adoption of immigrant voting rights. A 10 percentage point higher proportion is associated with an approximately 9 percentage point lower probability of the introduction of voting rights for non-citizens. We do not observe that the socio-economic characteristics of the foreign population make a difference in this relationship. Municipalities involved in a municipality merger are 28 percentage points more likely to adopt non-citizen voting rights. There is no systematic difference in this likelihood that depends on whether the municipality has a parliament rather than an assembly. Primarily Protestant municipalities, which knew non-citizen voting rights for centuries in their parishes, are more likely to adopt non-citizen voting rights. In contrast, primarily Romansh-speaking municipalities, which form a minority in the mainly Swiss-German-speaking canton, are less likely to enfranchise foreigners. Consistent with the preference-based hypotheses, municipalities that revealed stronger reservations towards immigration before 2004 are less likely to share power and municipalities where more citizens supported lowering the voting age to 18 from 20 are more likely to do so. Finally, a higher exposure to foreign seasonal workers (who are not directly affected by franchise extensions) is positively correlated with power sharing, with a 10 percentage point higher fraction being related to about an 18 percentage point higher probability of introducing voting rights for non-citizens.

An analysis of the two popular initiatives in the canton of Zurich complements the evidence for Grisons. Based on a longitudinal design, we find that an increase in the share of the young population raises support for the constitutional amendment. According to our results, an increase in the proportion of the foreign population by 10 percentage points reduces the vote share in favor of the opting-in clause by 3.5 percentage points. In this, the socio-economic composition of the foreign population again does not seem systematically related to the willingness to share power. The cross-sectional correlations for reservations towards immigration and the support for a lower voting age are similar to the ones in the analysis for the canton of Grisons, but quantitatively less pronounced.

Summing up, our evidence from two case studies on the drivers of power sharing in Switzerland suggests that instrumental as well as preference-based motives play a role in citizens’ willingness to enfranchise non-citizens. While we find evidence that is consistent with the power dilution hypothesis, the specific fiscal threat hypothesis appears to be less predictive. Preferences toward immigration seem to be strongly related to the willingness to share power. Furthermore, municipality mergers—to some extent allowing the questioning of prior power structures—seem to work as a quantitatively important catalyst for power sharing.

Our institutional context and empirical evidence complement previous qualitative as well as quantitative studies primarily focusing on the introduction of non-citizen voting rights through national parliaments.Footnote 6 An exception, and closest to our work, is the concurrent independent research by Koukal et al. (2020), who investigate electoral support of non-citizen voting rights at the municipal level in 33 cantonal referendums in Switzerland. As in our analysis on the actual adoption of these rights in the municipalities of Grisons, they find that a larger share of foreigners as well as a population of foreigners that is culturally more distant to the resident population reduces voters’ support in the referendums. This effect is largely driven by observations from comparatively smaller municipalities with town meetings and thus a more direct involvement of citizens in local politics. Related work adopting a cross-country design is by Toral (2015), who studies 33 democracies between 1960 and 2010. He derives hypotheses based on incumbent governments’ incentives to adopt non-citizen voting rights to maintain political power. He documents that left-wing governments are more likely to pass relevant legislation. In a series of studies, Earnest (2006, 2015a, b) considers the role of domestic politics and national characteristics on the one hand, and transnational factors on the other. The results suggest that the former is particularly relevant for the comprehensiveness and the latter for the timing of the introduction of non-citizen voting rights. His main analyses are based on data for 25 democracies between 1975 and 2010. In recent work, Kayran and Erdilmen (2020) replicate in a panel of 28 democracies between 1980 and 2010 the finding that a stronger representation of left-wing parties accelerates the adoption of non-citizen voting rights at the local level. The same holds for countries with less permissive immigration regimes. In contrast, a larger share of resident foreigners delays it. A common characteristic of most of this earlier work is that democratic inclusion is studied as a top-down process and analyzed in a cross-country setting.Footnote 7 In our work, we study power sharing as a bottom-up process of democratization that engages individual citizens who decide about non-citizen voting rights in their municipality of residence. This allows us to analyze more directly how citizens’ interests and preferences shape their willingness to adopt more inclusive democratic institutions than when such institutional changes are decided top-down. Furthermore, we are able to compare jurisdictions within one country and thus within a more homogeneous institutional setting. While the bottom-up process is not very common (but also exists in other countries like the United States, see e.g., Hayduk and Coll 2018), we still consider the insights relevant for and transferable to countries with a top-down process. In particular, the integration of immigrants might be similarly hampered if top-down power sharing is not supported by the citizens due to similar conditions as the ones studied here.

Our work also contributes to the positive analysis of franchise extensions in general. So far, the primary focus has been on extensions to the poor and to women (see, e.g., Aidt and Jensen 2014, and Doepke et al. 2012 for a review of the related literature). Particularly interesting for our context is recent work on power sharing related to the introduction of female suffrage at the municipal and cantonal level in Switzerland by Koukal and Eichenberger (2017). They provide evidence that power sharing was deferred because men held substantial political power in the directly democratic municipalities.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. Section 2 discusses the institutional and historical context, both in the canton of Grisons and in the canton of Zurich. The theoretical considerations on the drivers of power sharing are introduced in Sect. 3. Section 4 describes the compiled data sets, the operationalization of the various variables, and the empirical strategies for the two quantitative case studies. Sections 5 and 6 present the results of the two respective analyses. Section 7 offers some concluding remarks.

Data source: ELECLAW (Schmid et al. 2019)

Non-citizen voting rights across Europe in 2015. Notes: The inclusiveness of non-citizen voting rights refer to the local legislative. The indicator ranges from 0 to 1 and captures two types of eligibility restrictions and one access restriction. The former refer to (i) the length and status of residence and (ii) to limiting the rights to citizens of specific countries. The latter refers to electoral registration procedures. Higher values (darker colors) indicate more inclusive regimes.

2 Institutional and historical context

Voting rights are generally bound to individuals’ legal citizenship in some jurisdiction. However, in some countries voting rights are also granted to resident non-citizens, although these rights are often restricted. For example, they may require a minimum duration of residence in the country or some subnational jurisdiction, and frequently only apply to the local or regional level (and only rarely to the national level) of politics.Footnote 8 Figure 1 depicts the current situation of local voting rights for non-citizens in Europe regarding the right to vote in elections to the local legislative based on ELECLAW (Schmid et al. 2019). Low values indicate highly restrictive regimes, while high values indicate more inclusive ones. Switzerland is not coded, as the corresponding law is not nationally homogeneous.

In Switzerland, the country’s federal organization leaves the competence to introduce non-citizen voting rights to the cantons. As a result, the corresponding situation in Switzerland varies at the subnational level.Footnote 9 In 2019, eight out of the 26 cantons offer either some form of non-citizen voting rights at the cantonal level or an opting-in regime allowing their municipalities to adopt relevant legislation. Figure 2 visualizes the situation in detail. Two cantons offer active non-citizen voting rights (elections and ballot voting) at the cantonal, and active and passive voting rights at the municipal level (i.e. Jura and NeuchâtelFootnote 10), two cantons grant active and passive voting rights at the municipal level (i.e. Fribourg and VaudFootnote 11), one canton limits the extended franchise to an active voting right at the local level (i.e., GenevaFootnote 12) and three cantons leave it as an option to their municipalities (i.e., Appenzell a.R., Basel-Stadt, and Grisons). This situation is the result of a large number of attempts in the different cantons to introduce non-citizen voting rights. Adler et al. (2015) document a long list of cantonal votes (31 in total in 16 different cantons) on popular initiatives proposing amendments to the cantonal constitutions or on referendums regarding changes in the cantonal electoral law that in most cases were rejected. Only in Geneva, was a popular initiative of 2005 successful, with 52.3% yes-votes leading to the introduction of non-citizen voting rights at the municipal level. The failed attempts to introduce non-citizen voting rights include the two initiatives in the canton of Zurich that we analyze below. In most of the successful cases, the introduction was part of a general revision of the cantonal constitution and there was no separate vote on the aspect of power sharing with non-citizens. This also holds for the canton of Grisons, where, in 2003, citizens approved the completely revised cantonal constitution.Footnote 13

2.1 Non-citizen voting rights in the canton of Grisons

In the canton of Grisons, an opting-in regime for non-citizen voting rights was included in the draft of a new and totally revised constitution. The protocols of the parliamentary debate list a series of arguments for why municipalities should be allowed to adopt a more inclusive electoral law. They echo the arguments discussed in normative as well as in positive political theory. Regarding the former, offering the opportunity to vote has been seen as a duty to engage in municipal matters as much as a right. The positive reasoning of supporters and opponents either emphasized or questioned the motivational effects on integration and the intention to become naturalized.Footnote 14

The new constitution was approved on May 18, 2003 in a popular vote with a proportion of 59.7% yes-votes. As of January 1, 2004 the revised constitution of the canton of Grisons in article 9, subparagraph 4 allows (but does not require) its municipalities to enfranchise its resident foreigners for local issues.Footnote 15 According to this opting-in regime, they are allowed to grant active as well as passive electoral rights and also decide on any residence requirements. Municipalities in the canton of Grisons traditionally have high autonomy, and political decision-making at the local level is important. Among other things, citizens decide on local income tax, primary and secondary education, fire protection, welfare spending (social assistance), and local infrastructure (streets, water, sewage, etc.). Municipalities spend 42% (2016) of total cantonal expenditures. They have an elected executive and important decisions are made either in municipal assemblies and/or in elected municipal parliaments.

Of the 208 municipalities in 2004, 71 (former) municipalities had adopted non-citizen voting rights by January 1, 2017. This is not easily observable from today’s perspective, as many of the municipalities merged over the thirteen-year period. In fact, as of January 1, 2017, there were only 112 municipalities left, of which 23 offer non-citizen voting rights. We consider this important procedural and institutional aspect in the theoretical and empirical analyses below. In 13 municipalities that maintained their boundary, the franchise was extended in the context of either a partial or total revision of the municipal constitution. In 57 (former) municipalities that merged to become 10 larger municipalities, half (i.e. five) of the latter introduced non-citizen voting rights in their new constitution, although none of the earlier municipalities had had them. In the five other cases, at least one of the former municipalities had already offered non-citizen voting rights. The new municipal constitutions brought about by the many mergers in the canton did not involve non-citizen voting rights in all cases however. Figure 3 shows a map of the municipalities in the canton of Grisons that adopted non-citizen voting rights as of January 1, 2017.Footnote 16

2.2 Popular initiatives on the introduction of an opting-in regime for non-citizen voting rights in the canton of Zurich

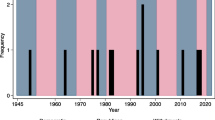

Citizens in the canton of Zurich decided on two very similar popular initiatives on the introduction of an opting-in regime for non-citizen voting rights in 1993 and in 2013.

Electoral support for an opting-in regime for non-citizen voting rights in 310 municipalities in the canton of Zurich in 1993 and 2013. Note: Correlation of the vote shares supporting the introduction of an opting-in regime for non-citizen voting rights across municipalities in the canton of Zurich in 1993 and 2013. Dots on the dashed \(45{^{\circ }}\)–line indicate an equal yes-share in both votes. Dots below (above) indicate a lower (higher) share in 2013 than in 1993.

The first initiative of 1993, titled “for an optional voting right for foreigners at the municipal level”, was launched by a committee formed by Social Democrats and supported by the union syndicate of Zurich (German: Gewerkschaftsbund Zürich). The second one in 2013, titled “for more democracy (optional voting rights for foreigners at the municipal level)”, was submitted by a non-partisan platform engaged in migration issues.Footnote 17 Both initiatives proposed granting municipalities the right to adopt active as well as passive non-citizen voting rights. They included a minimum requirement for residency in Switzerland, and, in the second initiative, also a personal application (rather than automatic registration in the voting register) (Abstimmungszeitung 1993, 2013). The cantonal parliament recommended rejection of the initiatives in both cases, the share of no-votes being 56.3% in 1993 and 57.8% in 2013. The rejection at the ballot was even more pronounced, with 74.5% of the active voters saying no in 1993 and 75.0% in 2013. Figure 4 shows that the vote outcome across municipalities still varied substantially in the two years and also within municipalities over time. The many dots below the diagonal indicate a decline in electoral support for the proposal in many municipalities over the twenty-year period.

3 Theoretical considerations on power sharing with non-citizens

We model the adoption (and support) of non-citizen voting rights in a politico-economic environment in which power sharing is a bottom up process. Based on an individual calculus, citizens trade-off instrumental interests and value-based reasons for why they support or reject an extension of the franchise to foreigners. Accordingly, our theoretical framework involves two sets of hypotheses. In a first set of hypotheses, we study the conditions under which the expected costs or individually perceived risks of power sharing are expected to be higher and thus the support for non-citizen voting rights to be lower.Footnote 18 In a second set of hypotheses, we capture preference-based conditions in terms of experiences and attitudes that are expected to affect the willingness to support power sharing with fellow resident non-citizens. Of course, a distinction between drivers from the outside and motivation from the inside is difficult and primarily serves as an organizational principle.

3.1 Citizens’ instrumental interests

In essence, citizens are expected to support power sharing less if they are concerned about losing out in the political process and in the local economy more broadly (see, e.g., Iturbe-Ormaetxe and Romero 2016; Dolmas and Huffman 2004; Mayr 2007; Ortega 2010 and Razin et al. 2002). We group these possible concerns under two general hypotheses.

Power dilution hypothesis—The more political influence an individual citizen has to give up, the less likely it is that a municipality will adopt non-citizen voting rights. This aspect holds in particular when municipalities are smaller or when the share of foreigners who are to be enfranchised is higher.Footnote 19 The latter aspect gets especially relevant if foreigners are expected to hold systematically different policy preferences and to shift the median voter position, often referred to as cultural or fiscal threat (see below). In contrast, an individual citizen loses relatively less in direct participation possibilities if decision power in many issues is already delegated to an elected municipal parliament (rather than maintained among the voters attending municipal assemblies).Footnote 20 A corresponding argument for the extension of the franchise to women is theoretically derived and empirically tested for the support of female suffrage in Swiss cantons by Koukal and Eichenberger (2017). Moreover, voting rights empower beyond the political sphere.Footnote 21 Accordingly, the more unemployed and less educated people there are among the citizenry, the more reluctant they are to strengthen the relative position of foreigners.Footnote 22 Finally, the additional loss in political influence of granting non-citizen voting rights is lower when citizens decide to merge municipalities in the first place. In addition, municipal mergers generally require or at least invite a total revision of the municipal constitution. In this context, non-citizen voting rights get on the political agenda more easily, so that municipal mergers act as a catalyst for institutional reforms.

Fiscal threat hypothesis—Depending on the economic status of foreigners compared to that of resident citizens, foreigners - if they were to have the right to vote - would support a different bundle of publicly provided goods and services as well as a different level of social welfare spending (see, e.g., Vernby 2013). A specific prediction can be derived based on the median voter model for redistributive taxation by Meltzer and Richard (1981). If the extension of the franchise leads to a situation in which the new median voter is relatively poorer, a higher level of welfare spending is implemented. A similar argument can be derived for additional spending for public services. Due to this fiscal threat, citizens are less likely to grant non-citizen voting rights if many citizens have high incomes or if there is a relatively higher welfare risk among the resident foreigners. A similar concern can arise if foreigners hold systematically different cultural beliefs about the role of government in redistribution and the provision of services (see Gonnot 2020). In related evidence for member countries of the European Union, Fauvelle-Aymar (2014) shows that more educated citizens harbor stronger reservations towards immigrants from poor countries when the latter have the right to vote.

3.2 Four preference-based hypotheses

Apart from instrumental considerations, we would expect that an individual’s experiences, norms, and attitudes are an additional important driver of the willingness to share power and will shape an individual’s perception of the cost of implementing non-citizen voting rights. We formulate a series of hypotheses about why, based on their experiences and attitudes, citizens are more or less likely to support their introduction.

Hypotheses related to minority experience and minority status—There are at least two countervailing forces motivating minority support for non-citizen voting rights. On the one hand, experiencing and personally knowing the situation of belonging to a cultural minority within a larger jurisdiction increases the understanding of and sympathy for members of other minorities (a mechanism captured in the rejection-identification model in social psychology going back to Tajfel 1978). On the other hand, minorities are in an even weaker position when the pool of decision-makers is increased. In this case, minorities in power in some lower level jurisdiction are reluctant to share power with minority out-groups.

In the context of the canton of Grisons, the latter argument is particularly relevant, as cultural policy is at least partly a competence of the municipalities. In municipalities with a strong presence of the two language minorities Romansh and Italian (the majority language in the canton is Swiss German), power sharing is therefore less likely. A similar argument regarding local identity refers to ancestry (i.e. the historical origin of population groups). In Grisons this holds for the Walser (see footnote 5 above).

Contact hypothesis—Beliefs about the consequences of sharing power with foreigners might be partly nurtured by prejudices concerning the preferences of these fellow residents. In this situation, more intensive contact between citizens and non-citizens could reduce relevant prejudices. This is the basic hypothesis of Allport’s (1954) intergroup contact theory. A rich literature has studied this aspect for attitudes towards immigrants (see, e.g., Green et al. 2016, 2020 and Paluck et al. 2019 for a review).

Intergroup contacts might thus be a counterforce to the fear of power dilution discussed above, making the extension of the franchise to non-citizens more likely with a higher proportion of foreigners in the municipality. The two forces can at least partly be separated when non-resident foreign seasonal workers are considered. Their presence makes encounters between foreigners and resident citizens more likely. However, they are not eligible to vote even with non-citizen voting rights as these are generally restricted to resident non-citizens. Thus power sharing is expected to be more likely with a larger share of non-resident foreign seasonal workers, given any level of resident foreigners in the municipality. To pin down the contact argument with non-resident foreigners empirically is, of course, difficult, as their presence is higher in more touristic municipalities, which might differ from other municipalities in many other ways.

Hypotheses related to attitudes and ideology—For ideological and strategic reasons (i.e. electoral support from the newly enfranchised), political parties on the left of the political spectrum tend to be more favorable towards immigrants and non-citizen voting rights (see, e.g., Howard 2010). The opposite holds true for parties on the right. In municipalities with a stronger support of left parties, the introduction of non-citizen voting rights is thus expected to be more likely and vice versa for right of center parties. More generally, with a larger fraction of citizens harboring reservations towards immigration and immigrants - almost tautologically - the adoption of non-citizen voting rights is less likely. Conversely, with a larger proportion of citizens supporting the idea of political inclusion, power sharing with foreigners is also expected to be more likely. Preferences for political inclusion have been previously revealed in a popular vote on the lowering of the voting age to 18 (rather than 20). And inclusion has been practiced in the Protestant church for a long time.Footnote 23 These latter aspects can be related to the concept of individual-level disposition against hierarchy in social dominance theory (see Sidanius et al. 2017 for a review).

4 Data and empirical strategies

Based on a series of different data sources, two data sets for the cantons of Grisons and Zurich are compiled to empirically study the determinants of power sharing. In the following, we briefly explain these data sets as well as the empirical strategies we apply in analyzing them.

4.1 Data for the canton of Grisons

In order to analyze the determinants of power sharing, we define the base sample to be the set of municipalities as they existed on January 1, 2004, i.e., when the new cantonal constitution came into force. Our estimation sample thus consists of 208 observations (municipalities). For each of these jurisdictions, we collect information about their characteristics as of the beginning of 2004, capturing the variables put forward in the theoretical hypotheses. We thus focus on statistical measures that are not themselves potentially affected by the new constitution (or more specifically the introduction of non-citizen voting rights) but are predetermined. Moreover, we record whether the original jurisdictions as in 2004 adopted non-citizen voting rights by January 1, 2017.

Dependent variable: adoption of non-citizen voting rights

Data on the introduction of non-citizen voting rights is primarily from the Bureau of Municipalities of the canton of Grisons (German: Amt für Gemeinden). This data is supplemented with additional information about which municipalities introduced non-citizen voting rights before, with or after a municipal merger based on a list compiled by (Adler et al. 2015) as well as from individual municipalities’ constitutions and webpages. The dependent variable is defined as an indicator set to 100 if the respective municipality introduced non-citizen voting rights prior to January 1, 2017, and to zero otherwise. This simplifies the reading of the coefficients in the empirical analysis in terms of percentage points. In our sample, 71 of the 208 municipalities adopted non-citizen voting rights by 2017.

Explanatory and control variables

Several of the proposed determinants of non-citizen voting rights refer to the socio-demographic characteristics of the Swiss and foreign population in each municipality. As we want to understand the decision-making of the citizens vis-à-vis their fellow non-citizen residents, we capture their characteristics in separate variables, if available. The general variables on education and unemployment therefore refer to Swiss citizens only, and separate variables measure the education, professional skills, language skills (i.e. the fraction that speaks at least one of the municipality’s main languages) and unemployment of foreign residents. Information about the proportion of the population in three age categories (up to 34, 35 to 65, and older) and the share with a high-income is only available for the whole municipality. Other municipality characteristics involve the population size (in logarithmic terms) and the percentage of foreigners (resident and non-resident). Table E.1 in Appendix E provides an overview of the descriptive statistics.Footnote 24 The correlation between the main explanatory variables is documented in Table E.3 in Appendix E.

A municipality’s legislative body either takes the form of an assembly, a parliament or an assembly combined with a parliament. The indicator municipal parliament takes a value of one in the latter two cases. In 2004, 15 out of the 208 municipalities had a municipal parliament. Three of them were involved in a merger. By 2017, the number only slightly increased to 17 municipalities with either a municipal parliament or a combination of parliament and assembly.

The variables we use to approximate minority experience include the fraction of Italian- and Romansh-speaking citizens, as Swiss German is the majority language, as well as an indicator variable for the municipality’s Walser origin, a historical ethnic minority with a distinct cultural heritage.

Attitudes and political preferences are measured based on voting behavior in elections and on particular popular votes. A number of referendums on the naturalization of specific groups of foreigners, citizenship rights, the asylum law, and the regulation of immigration allow us to infer preferences towards immigration and immigrants in general on a local level. Specifically, we conducted a principal component analysis based on the vote outcomes of 13 popular initiatives and referendums on the topics mentioned.Footnote 25 Citizens’ political preferences are more broadly approximated by the fraction of votes for the Social Democratic Party (on the left) and for the Swiss People’s Party (on the center-right) in the election for the Swiss National Council in 2003. Preferences for political power sharing in general are captured by the proportion of people who voted in favor of lowering the voting age to 18 in 1991.Footnote 26 Historical experience with non-citizen voting rights in the Protestant church is captured by the proportion of Protestants in the municipality.

Since 2004, following a number of municipality mergers, the number of municipalities in the canton of Grisons significantly decreased from originally 208 to 112 in 2017. As a consequence, the 71 earlier jurisdictions that introduced non-citizen voting rights over time corresponded to 23 municipalities in 2017. They can be classified into three groups: (i) municipalities that introduced non-citizen voting rights via a legislative decision (this can either be municipalities that were not involved in any merger (13 cases) or merged municipalities, where non-citizen voting rights were introduced after the merger (no case so far); (ii) municipalities that introduced non-citizen voting rights in conjunction with a merger, whereby none of them had any non-citizen voting rights before (5 cases); and (iii) municipalities which adopted the non-citizen voting rights following a merger, whereby at least one of the municipalities already had non-citizen voting rights before (5 cases). Overall, 58 out of the 71 former jurisdictions with non-citizen voting rights by 2017 were involved in a municipality merger after 2004. Not every merger led to the introduction of non-citizen voting rights however. To study the link between municipality mergers and power sharing, we define an indicator variable set to one for jurisdictions which were involved in a municipal merger between 2004 and 2017.

4.2 Data for the canton of Zurich

For the canton of Zurich, we collect, whenever possible, the same variables as listed for the canton of Grisons. Due to the panel setting, we do this for 1993 as well as for 2013, or years just before, for example, in the case of partisan support. The data refer to the 155 municipalities of the canton for which a complete set of control variables is available.Footnote 27 No mergers occurred during our observation period.

Dependent variable: support for non-citizen voting rights

The support for non-citizen voting rights is measured based on the yes share for the two popular initiatives on a range of 0 to 100 percent. As stated above, both initiatives were rejected, leaving us with an unweighted mean for the average yes share across the two popular votes of 20.82. Figure 4 above shows that there is still quite some variation in support within municipalities over time, i.e., for the same level of support in 1993, say 20% yes, the yes share varies between 11% and 20% in 2013.

Explanatory and control variables

The variables are defined as described above for the canton of Grisons. National election results capturing partisan preferences in the population refer to the elections in 1991 and 2011. For reservations towards immigrants and immigration, results for the first principal component for the same set of votes are considered and allow a comparison with the results for the canton of Grisons. An overview with descriptive statistics is provided in Table E.4 in Appendix E.Footnote 28

4.3 Empirical strategies

Two different strategies are applied to study the determinants of power sharing in the two cantons. A cross-sectional approach based on a multiple regression analysis is chosen for the canton of Grisons. We estimate a series of linear probability models using heteroskedasticity-robust standard errors. As we have to exploit variation across municipalities, we cannot control for unobserved time-invariant municipality characteristics, thus increasing the risk of an endogeneity bias. In order to reduce omitted variable bias, we adopt a control strategy that involves a set of basic control variables capturing the socio-demographic characteristics of municipalities in each specification. Specifically, a baseline specification including the proportion of foreigners in the municipality is expanded with different sets of additional explanatory variables related to the different hypotheses, always conditioning on the basic set of controls. However, with this strategy, due to possible sorting of foreigners into municipalities, we might also underestimate the effect of the proportion of foreigners on the adoption of non-citizen voting rights. This issue arises, for example, if reservations towards foreigners affect both the residency choice of foreigners across municipalities as well as the introduction of non-citizen voting rights (see Slotwinski and Stutzer 2019 for direct evidence on immigrant sorting due to resident citizens’ attitudes). Please note, however, that we address this latter aspect by explicitly adding a proxy measure for citizens’ policy preferences regarding immigration as an additional explanatory variable in Table 3. Still, our analysis remains correlational. Alternative, more experimental settings in which power sharing can be studied quantitatively, however, are likely to remain scarce. Our analysis comparing the correlates for municipalities in the same institutional setting should thus be compared with cross-country studies.

A panel approach is applied for the case of the canton of Zurich as we observe two votes for the same municipalities on rather similar propositions. This allows us to control for time-invariant municipality characteristics, reducing the concerns about omitted variable bias. In this case, we thus exploit within-municipality variation over time. Obviously, we are not observing actual introductions of non-citizen voting rights though. We estimate least squares models with the fraction of yes votes as the dependent variables conditioning on municipality fixed effects and clustering standard errors at the municipal level. We deviate from this strategy for explanatory variables which do not vary over time. In this case, we again exploit the variation across municipalities.

5 Results for the case of the canton of Grisons

The estimation results are presented in two steps. First, we concentrate on the factors that capture the instrumental considerations of citizens. Second, we focus on the preference-based motives related to power sharing. We have chosen a coding of the variables so that the point estimates can be compared as good as possible across determinants but in particular between Tables 1, 2, 3 and Tables 4 and 5.Footnote 29

5.1 Instrumental determinants of power sharing

Table 1 shows the partial correlations between the likelihood of having adopted non-citizen voting rights by 2017 and measures approximating citizens’ instrumental interests, in particular related to power dilution, conditioning on a series of baseline control variables.

Across all the specifications in Table 1, the proportion of foreigners is negatively related to the adoption of non-citizen voting rights. The coefficient in specification (4) indicates that in municipalities with a ten-percentage-point higher fraction of foreigners, the probability of introducing non-citizen voting rights is 8.8 percentage points lower. This observation is consistent with the hypothesis that citizens are more reluctant to share power when relatively more people were to be newly enfranchised. This relationship persists independently of whether we include indicators for municipality merger and for parliament as additional explanatory variables.

According to specification (1) there is a negative relationship between the adoption of non-citizen voting rights and municipality size as measured in natural log terms. Specification (2) suggests that this is at least partly driven by the fact that small municipalities are more likely to be involved in a merger and thereby also adopt non-citizen voting rights. If a municipality is part of a merger during the sample period, it is about 29 percentage points more likely to adopt non-citizen voting rights by 2017. This also holds in specification (5) if we exclude municipalities that have adopted non-citizen voting rights in the context of a local governmental reorganization involving at least one municipality that had adopted such rights before. The differential decreases, however, and amounts to about 14 percentage points. The observation for municipal mergers is in line with the hypothesis that they work as catalysts of power sharing. The presence of municipal parliaments is another factor partly explaining why larger municipalities are less likely to introduce non-citizen voting rights. Municipal parliaments are more prevalent in larger municipalities and their presence seems to be negatively correlated with non-citizen voting rights at least in the full sample covered in the specifications (3) and (4). There is thus no support for the hypothesis that power sharing is more likely where citizens have already delegated some political power to representatives.

The estimates presented in Table F.1 in Appendix F, taking into account foreigners’ characteristics, do not indicate that the relationship of power sharing and the fraction of foreigners is systematically moderated by whether foreigners are more or less educated, skilled or unemployed. For this empirical test, we define variables indicating whether a municipality has a proportion of foreigners above the median and whether the proportion of poorly educated, low skilled and unemployed foreigners is above the median. We include these measures of foreigners’ characteristics together with interaction terms with the indicator for an above-median foreigner share in separate specifications. Overall, no clear pattern emerges, thus providing little systematic evidence for the fiscal threat hypothesis related to the welfare risk among foreigners.

The variables included as controls, capturing the socio-economic composition of the citizenry in terms of age, education, unemployment and income across municipalities in Grisons do not seem to be systematically related to the adoption of non-citizen voting rights. Thus, the results do not indicate that less-educated or disadvantaged citizens particularly oppose non-citizen voting rights.

5.2 Preference-based determinants of power sharing

In this section, we explore whether preference-based determinants are predictive for the adoption of non-citizen voting rights. For these analyses, we add separate variables for municipality mergers, the size of the population as well as the share of local foreigner to the set of baseline controls.

Table 2, specification (1) shows that in municipalities with a large exposure to non-permanent resident foreigners, non-citizen voting rights are more likely to be adopted. Compared to the permanent population, a ten-percentage-point increase in this group of primarily seasonal workers in the service industry is related to an 18-percentage-point higher probability of non-citizen voting rights in a municipality. This is consistent with the idea behind the contact hypothesis. However, caution is warranted, as the risk of a misinterpretation looms large. Because there are more seasonal workers in municipalities with a large tourist industry, the variable might also pick up other local characteristics related to a more open stand regarding non-citizen voting rights. When we statistically consider the fraction of non-permanent resident foreigners, we also observe that the negative partial correlation for the fraction of resident foreigners becomes larger. A ten-percentage-point increase then relates to an approx. -14-percentage-point (rather than -8.8-percentage-point) lower probability that a municipality will introduce non-citizen voting rights.

According to specification (2), for municipalities with strong language minorities, we find ceteris paribus lower probabilities to adopt non-citizen voting rights of between 16 percentage points (not statistically significant) for Italian speaking municipalities and 32 percentage points for Romansh speaking municipalities. Language minorities thus seem reluctant to share power with non-citizen co-residents who might not well speak the local language or instead speak the majority language, i.e. Swiss German. This might reflect a particular concern regarding the maintenance of their specific culture that is closely tied to their language. In specification (3), for the 41 municipalities with a Walser heritage, we do not observe that they are more or less likely to adopt non-citizen voting rights.

In Table 3, political attitudes and preferences are considered as additional explanatory variables. Specification (1) suggests that non-citizen voting rights are more likely in municipalities where a large fraction of the voters supported the Social Democratic Party in the last national elections before 2004. However, the point estimate is far from statistically significant and thus offers no clear evidence for the hypothesis that parties on the left expect to benefit more from expanding the franchise to non-citizens. Even contrary to this latter hypothesis, a positive partial correlation for the vote share of the Swiss People’s Party is also observed, a party which at the national level holds strong reservations regarding immigration. While the issue of a potential ecological fallacy looms large, the result might also reflect that the candidates of the Swiss People’s Party of the canton of Grisons pursued rather centrist positions and partly joined a new centrist party (the Conservative Democratic Party) in 2008.

When including a measure capturing reservations towards immigrants and immigration in specification (2), we observe a strong and statistically significant negative correlation with the adoption of non-citizen voting rights. For a one standard deviation increase in the measure based on previous national votes (i.e. 0.2), we calculate a roughly 11-percentage-point lower probability. This finding is consistent with the hypothesis that local norms and attitudes play a role in individuals’ decision making, also when conditioning on the share of local foreigners.

In municipalities where in 1991 a larger fraction of the citizenry supported the reduction of the voting age to 18, we observe a higher probability of adopting non-citizen voting rights (specification 3). For a ten-percentage-point higher support, the probability is about 7 percentage points higher. According to specification (4), municipalities with a primarily Protestant population are more likely to adopt non-citizen voting rights. This might reflect that the Protestant church in the area of Grisons has allowed foreigners to participate in the local church congregation since the Reformation. However, as with the other characteristics, an interpretation has to be undertaken with the usual caution, given the cross-sectional nature of the analysis and the potential misattribution of the relationship, as variables like the fraction of Protestants could also be proxies for other factors (also known as the ecological fallacy).

6 Results for the case of Zurich

Tables 4 and 5 present partial correlations from least squares estimations, with the share of votes in percent supporting an opting-in regime of non-citizen voting rights as the dependent variable. We apply two different basic control strategies. On the one hand, there are results from estimations pooling two observations for each municipality, exploiting the variation across municipalities as well as over time. This strategy is adopted whenever the explanatory variable of interest does not vary over time and would be absorbed by municipality fixed effects. As before, we include baseline controls for the socio-demographic characteristics of the citizens and the size of the municipality. On the other hand, we include results from specifications with municipality fixed effects, thus effectively controlling for all the time-invariant municipality-specific factors related to the yes share. These specifications exploit the within municipality variation over time. In addition, we include a year fixed effect to control for a level shift over time. As this latter approach reduces omitted variable bias, we concentrate the presentation of the results on the fixed effects specifications when appropriate. It is important to keep in mind, though, that with a focus on the variation over time, any bias due to self-selection of citizens and non-citizens into municipalities is given relatively more weight in the estimation of the partial correlations.

6.1 Instrumental determinants of power sharing

Table 4 presents the specifications (1) without and (2) with municipality fixed effects. Consistent with our findings for the canton of Grisons, a larger fraction of foreigners is related to a lower support of an opting-in regime. The yes share is predicted to be 3.5 percentage points lower with an increase in the foreign population of 10 percentage points. If foreigners were more likely to move into municipalities that became relatively more open over time, the estimated partial correlation is a lower bound. This result again suggests that instrumental considerations about power dilution play a role in citizens’ support of non-citizen voting rights. In contrast, there is no clear evidence for the fiscal threat hypothesis as we do not find changes in the composition of the foreign population in terms of education, skills and unemployment to be related to popular support for an opting-in regime (see Table F.2 in Appendix F).

As there is no change over time in the presence of municipal parliaments, the partial correlation for the latter variable can only be measured in the cross-section. According to specification (1), there is a 2.4-percentage-point higher yes share in municipalities with a parliament conditioning on the population size. This finding is consistent with the hypothesis that the enfranchisement of additional groups is less costly for citizens if they have already delegated some power to an elected parliament.

Based on the second specification, we find for the basic variables capturing the socio-demographic composition of the municipalities that popular support of non-citizen voting rights is higher if there are more households with three and more people and if a larger fraction of the population is younger than forty. In contrast, a larger proportion of people 65 and older reduces support (with the fraction of people between 40 and 64 forming the reference group). The positive correlation for the young amounts to a 2.4-percentage-point higher yes share if there are 10 percentage points more young people in the municipality, the corresponding negative relationship for the older population amounts to -3.1 percentage points. A higher fraction of less-educated Swiss is negatively correlated with the yes share. However, the estimated coefficient is not statistically significant once unobserved municipality characteristics are considered. The fraction of high income residents and the rate of unemployment are not systematically related to the share of yes votes. While population size (in natural log terms) is positively correlated in the cross-section, a higher population over time, i.e. population growth, is negatively related to the yes share. The effect of a 10 percent population increase is small, though, and amounts to only about -0.5 percentage points.

6.2 Preference-based determinants of power sharing

Table 5 in specification (1) shows that changes in the fraction of voters with particular partisan preferences are correlated with changes in the yes share in support of an opt-in regime for non-citizen voting rights over time. For a 10-percentage-point higher support for the right-wing Swiss People’s Party (i.e., about a change by one standard deviation), the share of yes votes is reduced by 1.2 percentage points. The Swiss People’s Party in the canton of Zurich follows the national party line, taking a critical stance towards immigration and immigrants. The results for the party vote shares is consistent with the negative correlation between general reservations towards immigrants, as expressed in national popular votes and the share of yes votes on the specific amendment to the cantonal constitution in specification (2). For one standard deviation of more pronounced reservations (i.e. 0.148), the yes share is 3.9 percentage points lower.

In municipalities that previously showed higher support for power sharing vis-à-vis the young, we also observe higher support for the opting-in regime regarding an enfranchisement of foreigners. The corresponding correlations in specification (3) amount to 4.3 percentage points for a ten-percentage-point greater support for the voting right after the age of 18 in the early 1990s. Variation in political attitudes and preferences more generally and in related domains thus correlate in meaningful ways with popular support for an opting-in regime for non-citizen voting rights in the canton of Zurich.

7 Conclusions

The enfranchisement of foreigners is an important frontier in current institutional change in democracies. Normative questions arise not only regarding the why but also the how. While there is a rich exchange on the moral reasons for and against non-citizen voting rights, there is much less discussion on the rules that should be applied to adopt non-citizen voting rights. We want to contribute to the debate on these important normative questions with a positive analysis of the determinants of power sharing in a particular institutional context, i.e. an opting-in regime in which the citizens of individual municipalities decide on the introduction of active and passive voting rights for resident foreigners. Such a rule was introduced in the Swiss canton of Grisons with the totally revised constitution of 2004, allowing us to study democratic reforms within a uniform setting.

Over thirteen years, about 30% of the original municipalities adopted non-citizen voting rights in some form. We are not aware of any media coverage about pressure to introduce such rights, nor of negative experiences with the formal involvement of foreign residents. So far, no municipality has disenfranchised foreigners again. The adoption of non-citizen voting rights seems to be at least partly understood as an invitation and obligation to participate and to take on responsibility in municipal politics characterized by a strong militia system (an organizational principle according to which public functions are usually carried out part-time). Consistent with the power dilution hypothesis, we find that enfranchisement is less likely with a larger share of resident foreigners. Our analysis also reveals that the adoption of non-citizen voting rights is more likely in municipalities that are involved in a local reorganization. Municipal mergers seem to act as a catalyst in an institutional context that offers the flexibility for democratic reforms. Furthermore, we find that municipalities with a large language/cultural minority are less likely to formally involve foreigners. This observation substantiates the normative appeal of an opting-in rule that acknowledges the basic principle of self-rule in a context with many minorities. Finally, we observe that preference-based determinants seem to have additional explanatory power. In municipalities where people hold generally favorable attitudes towards power sharing, non-citizen voting rights are more likely to be adopted, while they are less likely to be adopted where citizens have expressed stronger reservations towards immigration in popular votes.

In a supplementary panel analysis, we study the electoral support for an opting-in regime for non-citizen voting rights directly. In the Swiss canton of Zurich, citizens decided on relevant initiatives twice in 1993 and 2013. In line with the evidence for Grisons—and in this case conditioning on time invariant municipality characteristics—municipalities with a higher share of resident foreigners show lower support for constitutional amendment. Furthermore, exploiting the cross-sectional variation in Zurich, higher support is observed in municipalities where a larger fraction approved the reduction of the voting age to 18 and lower support where reservations concerning immigration were stronger.

While our quantitative case study is embedded in an environment where people hold extensive experience with direct democracy, we think that there are at least two lessons that hold independently of this context. First, the opting-in regime can be seen as a social innovation that could be adopted also in other countries, and in fact has been discussed in the US context (Eisenberg 2015). Second, our empirical analysis tests for possible tensions regarding the support of non-citizen voting rights that would potentially also be at work (though less clearly observed and identified) in other places where non-citizen voting rights were introduced top-down. Our study thus allows assessing the conditions for the likely acceptance or rejection of non-citizen voting rights. While the process legitimacy cannot be achieved when taking these conditions into account in a top-down decision, the outcome legitimacy might still be positively affected.

Overall, politico-economic forces along with political preferences seem to shape the evolution of democratic institutions along the important dimension of non-citizen participation in politics. The constitutional arrangement of an opting-in regime for non-citizen voting rights seems to offer the institutional flexibility that supports peaceful reforms and acknowledges the autonomy of citizens in organizing their municipalities.

Notes

There is a large literature in normative political theory which mostly argues that non-citizens should not be permanently excluded from the right to vote in democracies (see, e.g., Bauböck 2015; Dahl 1989; Miller 2008; Pettit 2012; Rubio-Marin 2000, and for reviews, Blatter et al. 2017 and Song 2009). In constitutional law, there is similarly an understanding of the legitimization of state authority through the involvement of the affected people, holding in particular for self-government on the communal level.

In constitutional law, this refers to the idea of the state as an organization of authority that works towards internal unification and demarcation in order to maintain cohesion among its citizens. There is thus a congruence between the people who are permanently subordinated by the authority of the state and those who hold democratic political rights. Access to this unit of people is determined by the laws to attain and to lose citizenship. A corresponding reasoning is pursued in the decision of the German Constitutional Court when judging that the right of foreigners to vote at the municipal level in Schleswig-Holstein would be in violation of the constitution (BVerfG (Urt. vom 31.10.1990), E 83, 37 ff.) (see, e.g., Bäumler 2020 or Zuleeg 2000). A similar reasoning about the people as a unity that are subject of the authority of the state informs the legal discourse in France, prominent in the decision of the constitutional council requiring an amendment to the constitution in order to ratify the Maastricht treaty that newly offered citizens from other EU countries a voting right at the local level (Cons. const. (Décision du 9 avril 1992), 92–308) (see, e.g., Delemotte 2007).

Reviews of these arguments are provided in Munro (2008) and Ferris et al. (2020). A recent empirical literature has tried to rigorously test the different predictions (see, e.g., Ferwerda et al. (2020) with regard to political participation, Slotwinski et al. (2017) for legal norm compliance, or Slotwinski et al. (2020) on naturalization).

A general positive account on constitutional change is provided in Voigt (1999). The aspect of inclusiveness for democratic institutions is particularly emphasized in the theories of state formation of Acemoğlu and Robinson (2016). Participatory constitutional change is the focus in Contiades and Fotiadou (2016).

The Walser (Rhaeto-Romanic Gualsers) are an Alemannic ethnic group in the Alpine region. Coming from the Upper Valais they moved, from the late High Middle Ages onwards, South but primarily East and settled in various higher valleys in what became the canton of Grisons. Particularly in regions where the local language was Romansh or Italian, they maintained their distinct culture over centuries.

There is a rich literature of qualitative single country studies as well as comparative case studies that provide in-depth analyses on the discourse and conditions when parliaments engage in liberalizing or retracting non-citizen voting rights (see, e.g., Benhabib 2004; Hayduk 2006; Hayduk and Coll 2018; Howard 2010; Pedroza 2019; Soysal 1994 and the contributions in the special issues on “Who Decides? Democracy, Power and the Local Franchise in Cities of Immigration” of the Journal of International Migration and Integration in 2015, and “Voting Rights in the Age of Globalization” of the journal Democratization in the same year edited by Caramani and Grotz 2015). Another related literature documents in great detail the electoral inclusion of non-citizens and related changes in the law. The database ELECLAW, for example, covers the legal situation in 51 democracies in 2015 (http://globalcit.eu/electoral-law-indicators/) (Schmid et al. 2019). Finally, there is recent survey evidence from 26 European countries on people’s support of non-citizen voting rights on the national level. For all the countries, Michel and Blatter (2020) observe that a majority is rejecting it.

This also holds for the many countries that grant non-citizen voting rights at the local level. This is most prominently the case for the voting rights of EU citizens in EU countries outside of their home country introduced as part of the Maastricht treaty in 1992.

In Europe only Portugal, Ireland and the UK offer voting rights to special groups of non-citizens at the national level.

A detailed legal and historical description is provided in Müller and Schlegel (2017).

In the canton of Jura, non-citizens are automatically registered after at least ten years of residence in Switzerland and at least one year in the canton of Jura. In the canton of Neuchâtel, foreigners have to have lived in the canton for at least five years. Registration also occurs automatically.

In the canton of Fribourg, non-citizens have to reside in the canton for at least 5 years and have to hold permanent residence (permit C). In the canton of Vaud, non-citizens are granted the right to vote if they resided in Switzerland for at least ten years and three years in the canton. They have to hold a temporary or permanent residence permit (permit B or C).

The canton of Geneva requires a minimum residence duration of 8 years in Switzerland without additional restrictions considering the permit type.

Besides formal voting rights in the municipalities, various other forms of political participation for foreigners are possible at the communal level, in particular in church communities (see, e.g., Zaslawski 2016). The advisory participation of foreigners in municipal matters, for example, is provided for by statute in the constitution of the canton of Thurgau.

Appendix A states the constitutional clause in German and in English and reproduces some quotes from the official protocols.

Moreover, municipalities are not required to engage in any legal action in response to the constitutional clause. Thus municipalities are free not to become active in this area.

The conditions for the right to vote differ across municipalities, with, for example, the local residency requirement varying between permanent residency only (without any time requirement) and ten years (Bisaz 2017, p. 117). A list of the municipalities with additional information is provided in Appendix B.

Appendix C reproduces the texts of the two initiatives both in German and in English.

These arguments also hold when non-citizen voting rights are primarily introduced (and perceived) as an invitation (or even an obligation) to take on responsibility in the municipality, i.e. we still expect that they affect the trade-off, but just at a higher level of general support.

The reverse reasoning arises if a lack of qualified people who can serve in the municipal executive or in some other political body motivates the adoption of non-citizen voting rights (see Adler et al. 2015 for a relevant argument in favor of institutional reform), as this situation might be more of an issue in small municipalities. A prominent case is documented for the neighboring canton of Appenzell a.R., where one municipality made use of the opting-in regime to then elect a Dutch resident as mayor (p. 28).

Corresponding evidence, for example for the Swiss context, indicates a higher prevalence of left leaning positions among first and second generation immigrants (Strijbis 2014).

A corresponding analysis for female suffrage and the emancipation of women in Switzerland is provided by Slotwinski and Stutzer (2018).

An empirical test of this hypothesis is difficult however, as the same groups of disadvantaged citizens might support non-citizen voting rights to strengthen their electoral clout.

The Evangelical Reformed Regional Church of the Canton of Grisons has a long tradition in incorporating foreigners in their parishes. The constitution of 26 February 1978 declares in Article 4 that “The Protestant parish includes all persons of Protestant denomination resident in its territory who have not expressly declared that they do not belong to the Regional Church or have left it”.

Table E.2 in Appendix E offers separate descriptive statistics for municipalities that did and did not adopt non-citizen voting rights. For the former group, the average municipality has a population of 421 inhabitants, of whom 6 percent are foreigners. For the latter group without non-citizen voting rights, municipalities, on average, have 1,146 inhabitants and a share of foreigners of 9 percent.

Specifics regarding the loadings of the various propositions are described in Appendix D when individual variables are described.

A complete list of the variables, the corresponding coding, and the data sources are provided in Appendix D.

The municipal structure refers to January 1, 2018, when there were 166 municipalities. For eleven of these municipalities there are missing data for the socio-economic composition. This occurs if the number of people sharing some characteristic is below a certain threshold, as the corresponding number is then not published.

As no data for the fraction of non-resident foreigners is available before 2010 at the municipal level, we cannot consider the respective variable.

For indicator variables, the estimated coefficients of the linear probability model can be interpreted as differences in percentage points (as the dependent variable takes a value of 100, if a non-citizen voting right is in place, and zero otherwise). For variables capturing fractions of the population, the estimated coefficients indicate the difference in percentage points when the fraction changes from 0% to 100%. For continuous variables, the coefficients measure the difference in percentage points for a one unit change of the explanatory variable.

References

Abstimmungszeitung. (1993). Kantonale Volksabstimmung vom 26. September 1993.

Abstimmungszeitung. (2013). Kantonale Volksabstimmung vom 22. September 2013.

Acemoğlu, D., & Robinson, J. A. (2016). Paths to inclusive political institutions. In J. Eloranta, E. Golson, A. Markevich, & N. Wolf (Eds.), Economic history of warfare and state formation (pp. 3–50). Singapore: Springer.

Adler, T., Moret, H., Pomezny, N., Schlegel, T., Schwarz, G., & Müller, A. (2015). Passives Wahlrecht für aktive Ausländer: Möglichkeiten für politisches Engagement auf Gemeindeebene. Zürich: Avenir Suisse.

Aidt, T. S., & Jensen, P. S. (2014). Workers of the world, unite! Franchise extensions and the threat of revolution in Europe, 1820–1938. European Economic Review, 72, 52–75.

Allport, G. (1954). The nature of prejudice. Oxford: Addison-Wesley.

Bauböck, R. (2015). Morphing the demos into the right shape. normative principles for enfranchising resident aliens and expatriate citizens. Democratization, 22(5), 820–839.

Bäumler, J. (2020). Who are “the people” in the German constitution? A critique of, and contribution to, the debate about the right of foreigners to vote in multilevel democracies. Law, Democracy and Development, 24, 1–26.

Benhabib, S. (2004). The rights of others: Aliens, residents, and citizens. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bisaz, C. (2017). Das Ausländerstimmrecht in der Schweiz - Formen und Rechtsungleichheit. In A. Glaser (Ed.), Politische Rechte für Ausländerinnen und Ausländer? (pp. 107–140). Zürich: Schulthess.

Blatter, J., Schmid, S. D., & Blättler, A. C. (2017). Democratic deficits in Europe: The overlooked exclusiveness of nationstates and the positive role of the European union. Journal of Common Market Studies, 55(3), 449–467.

Caramani, D., & Grotz, F. (2015). Beyond citizenship and residence? Exploring the extension of voting rights in the age of globalization. Democratization, 22(5), 799–819.

Contiades, X., & Fotiadou, A. (Eds.). (2016). Participatory constitutional change: The people as amenders of the constitution. New York: Routledge.

Dahl, R. A. (1989). Democracy and its critics. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Delemotte, B. (2007). Le droit de vote des étrangers en France. Migrations Société, 6, 205–217.

Doepke, M., Tertilt, M., & Voena, A. (2012). The economics and politics of women’s rights. Annual Review of Economics, 4(1), 339–372.

Dolmas, J., & Huffman, G. W. (2004). On the political economy of immigration and income redistribution. International Economic Review, 45(4), 1129–1168.

Earnest, D. C. (2006). Neither citizen nor stranger: Why states enfranchise resident aliens. World Politics, 58(2), 242–275.

Earnest, D. C. (2015a). Expanding the electorate: Comparing the noncitizen voting practices of 25 democracies. Journal of International Migration and Integration, 16(1), 1–25.

Earnest, D. C. (2015b). The enfranchisement of resident aliens: Variations and explanations. Democratization, 22(5), 861–883.

Eisenberg, A. (2015). Voting rights for non-citizens: Treasure or fool’s gold? Journal of International Migration and Integration, 16(1), 133–151.

Fauvelle-Aymar, C. (2014). The welfare state, migration, and voting rights. Public Choice, 159(1–2), 105–120.

Ferris, D., Hayduk, R., Richards, A., Schubert, E. S., & Acri, M. (2020). Noncitizen voting rights in the global era: A literature review and analysis. Journal of International Migration and Integration, 21, 949–971.

Ferwerda, J., Finseraas, H., & Bergh, J. (2020). Voting rights and immigrant incorporation: Evidence from Norway. British Journal of Political Science, 50(2), 713–730.

Gonnot, J. (2020). Taxation with representation: The political economy of foreigners’ voting rights. Toulouse: Mimeo, Toulouse School of Economics.

Green, E. G. T., Sarrasin, O., Baur, R., & Fasel, N. (2016). From stigmatized immigrants to radical right voting: A multilevel study on the role of threat and contact. Political Psychology, 37(4), 465–480.

Green, E. G. T., Visintin, E. P., Sarrasin, O., & Hewstone, M. (2020). When integration policies shape the impact of intergroup contact on threat perceptions: A multilevel study across 20 European countries. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 46(3), 631–648.

Hayduk, R. (2006). Democracy for all: Restoring immigrant voting rights in the United States. New York: Taylor & Francis.

Hayduk, R., & Coll, K. (2018). Urban citizenship: Campaigns to restore immigrant voting rights in the US. New Political Science, 40(2), 336–352.

Howard, M. M. (2010). The impact of the far right on citizenship policy in Europe: Explaining continuity and change. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 36(5), 735–751.

Iturbe-Ormaetxe, I., & Romero, J. G. (2016). Financing public goods and attitudes toward immigration. European Journal of Political Economy, 44, 159–178.

Kayran, E. N., & Erdilmen, M. (2020). When do states give voting rights to non-citizens? The role of population, policy, and politics on the timing of enfranchisement reforms in liberal democracies. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies. (in press).

Koukal, A. M., & Eichenberger, R. (2017). Explaining a paradox of democracy: The role of institutions in female enfranchisement. CREMA working paper No. 2017-13, Zurich: Center for Research in Economics, Management and the Arts.

Koukal, A. M., Schafer, P., & Eichenberger, R. (2020). Enfranchising foreigners: What drives natives’ willingness to share power? CREMA working paper No. 2019-10, version 2020-05-30, Zurich: Center for Research in Economics, Management and the Arts.

Mayr, K. (2007). Immigration and income redistribution: A political economy analysis. Public Choice, 131(1–2), 101–116.

Meltzer, A. H., & Richard, S. F. (1981). A rational theory of the size of government. Journal of Political Economy, 89(5), 914–927.

Michel, E., & Blatter, J. (2020). Enfranchising immigrants and/or emigrants? Attitudes towards voting rights expansion among sedentary nationals in Europe. Ethnic and Racial Studies. (in press).

Miller, D. (2008). Immigrants, nations, and citizenship. Journal of Political Philosophy, 16(4), 371–390.

Müller, A., & Schlegel, T. (2017). Passives Wahlrecht für aktive Ausländer. In A. Glaser (Ed.), Politische Rechte für Ausländerinnen und Ausländer? (pp. 31–56). Zürich: Schulthess.

Munro, D. (2008). Integration through participation: Non-citizen resident voting rights in an era of globalization. Journal of International Migration and Integration, 9(1), 63–80.

Ortega, F. (2010). Immigration, citizenship, and the size of government. The BE Journal of Economic Analysis and Policy, 10(1).

Paluck, E. L., Green, S. A., & Green, D. P. (2019). The contact hypothesis reevaluated. Behavioural Public Policy, 3(2), 129–158.

Pedroza, L. (2019). Citizenship Beyond nationality: Immigrants’ right to vote across the world. Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania Press.