Abstract

This paper conducts laboratory experiments to investigate how the individuals with heterogeneous income levels endogenously select the institution in public good provision in a Tiebout-like environment. According to the experimental results, I find that heterogeneous individuals have different choices of contribution institutions. High-income individuals tend to participate in the voluntary contribution institution, but low-income individuals tend to choose the compulsory one. I also find that most high-income individuals in the voluntary contribution institution try to free ride on others. Therefore, although the vote-with-feet mechanism helps to sort heterogeneous individuals in different contribution institutions, it may not enhance the cooperation among the individuals in the voluntary contribution community.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

A congestible public good is neither purely private nor purely public good. It is nonrival when few people are using it but become rival when heavily used.

The TAX100% community represents the full and forced cooperation; the TAX0% community represents no cooperation and no free riding. Since the previous experimental results (see Ledyard (1995)) show that individuals are willing to contribute 40–60% of their endowment to the public good at the beginning of periods, I set up the third tax community, TAX50% community, for participants to choose and to examine whether the individuals are willing to be forced to contribute half of their endowments over all periods.

I randomly select five sessions of the VF treatment to simulate the structure of community choices in the NVF treatment. Because of the scarcity of experimental budget, this study only conducts five sessions of the NVF treatment. Since the distribution of community choice in each session of the VF treatment is very similar, I presume that conducting only five sessions of the NVF treatment may not affect the results.

Since subjects should answer all four questions correctly for the experiment to continue, the rate of correct answer in the quiz is \(100\%\). When subjects answer incorrectly, the screen of computer would show that “Your answer is incorrect. Please answer again.”

USD 1 is equal to NTD 30.8.

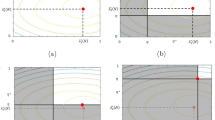

Individual i’s payoff function in the VCM community can be written as: \(\pi ^{VCM}_{i} = w_{i}- g_{i} + \alpha (g_{i} +\sum _{j\ne i} g_{j} )\), where \(\alpha <1\). To maximize individual i’s payoff, I get the F.O.C. \(\frac{\partial \pi ^{VCM}_{i}}{\partial g_{i}}= -1 +\alpha <0\). Thus, the dominant strategy is \(g^{*}_{i}= 0\). An numerical example: suppose 6 high-income individuals are in the VCM community, and one of them contributes 0 and each of the other 5 individuals contribute 20. The payoff of the individual who contributes 0 is equal to 40 (\(= 20 + 0.2\times 100\)), which is higher than the payoff with full cooperation (\(= 0 +0.2\times 120 =24\)).

For example, if all 12 subjects join in the TAX100% community, the total payoff should be 216, the payoff the high-income subject receives is 18, and the payoff the low-income subject receives is also 18; if 6 high-income subjects join in the VCM community and make a full contribution, and 6 low-income subjects join in the TAX100% community. Then, the payoff each high-income subject receives is 24, and the payoff each low-income subject receives is 12. The total payoff is also equal to 216 (\(= 24 \times 6 + 12 \times 6\)).

In the VF treatment, I have 10 sessions. Each session has 6 high-income participants and 6 low-income participants. Thus, in total, there are 60 high-income participants and 60 low-income participants.

Since it is trivial that the individual voluntary contribution is lower (higher) than his compulsory contribution in the TAX100% (TAX0%) community and the Mann–Whitney test is inappropriate for these special cases with the boundary of the distribution, I do not conduct the statistical test to compare the voluntary contribution with the compulsory contribution in the TAX100% or TAX0% community.

The method of calculating the contribution level is that summing up the individual contribution for a given community over 15 periods, and then dividing it by the number of periods the individual has spent in this particular community.

Since the interdependence of the decisions, I use session-level data as independent observations when discussing the over-time average contribution decisions.

The details of a robust rank-order test, please see Siegel and Castellan (1998).

I compare the average voluntary contributions under VF and NVF treatments using the data in the first 5 periods and in the last 10 periods. By the robust rank-order test, it shows that in the first 5 periods, the average individual contribution under VF treatment, 1.60, is significantly lower than that under NVF treatment, 3.15 (\(U= -\,1.32\), p value \(=0.09\)). But it is statistical insignificance in the last 10 periods (average contribution under VF and NVF treatment is 0.63 and 1.05, respectively; \(U= -\,1.09\), p value \(=0.14\)).

References

Ahn T-K, Isaac RM, Salmon TC (2008) Endogenous group formation. J Publ Econ Theory 10(2):171–194

Ahn T-K, Isaac RM, Salmon TC (2009) Coming and going: experiments on endogenous group sizes for excludable public goods. J Publ Econ 93:336–351

Banzhaf HS, Walsh RP (2008) Do people vote with their feet? An empirical test of Tiebout’s mechanism. Am Econ Rev 98(3):843–863

Buckley B, Croson R (2006) Income and wealth heterogeneity in the voluntary provision of linear public goods. J Publ Econ 90:935–955

Cherry TL, Kroll S, Shogren JF (2005) The impact of endowment heterogeneity and origin on public good contributions. J Econ Behav Organ 57:357–365

Ehrhart K-M, Keser C (1999) Mobility and cooperation: on the run, Working paper, CIRANO Scientific Series, 99s-24

Fischbacher U (2007) z-Tree: Zurich toolbox for ready-made economic experiments. Exp Econ 10(2):171–178

Gürerk Ö, Irlenbusch B, Rockenbach B (2006) The competitive advantage of sanctioning institutions. Science 312:108–111

Gürerk Ö, Irlenbusch B, Rockenbach B (2014) On cooperation in open communities. J Publ Econ 120:220–230

Hewett R, Holt CA, Kosmopoulou G, Kymn C, Long CX, Mousavi S, Sarangi S (2005) A classroom exercise: voting by ballots and feet. South Econ J 72(1):253–263

Innocenti A, Rapallini C (2011) Voting by ballots and feet in the laboratory. Giornale degli Economisti 70(1):3–24

Isaac RM, Walker JM (1988) Communication and free-riding behavior: the voluntary contribution mechanism. Econ Inq 26:585–608

Kosfeld M, Okada A, Riedl A (2009) Institution formation in public goods games. Am Econ Rev 99:1335–1355

Ledyard JO (1995) Public goods: a survey of experimental research. In: Kagel J, Roth AE (eds) Handbook of experimental economics. Princeton University Press, New York, pp 111–194

Oates WE (2006) The many faces of the Tiebout model. In: Fischel William A (ed) The Tiebout Model at Fifty: Essays in Public Economics in Honor of Wallace Oates. Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, Cambridge, MA, pp 21–45

Rhode PW, Strumpf KS (2003) Assessing the importance of Tiebout sorting: local heterogeneity from 1850 to 1990. Am Econ Rev 93(5):1648–1677

Robbett A (2014) Local institutions and the dynamics of community Sorting. Am Econ J Microecon 6(3):136–156

Robbett A (2015) Voting with hands and feet: the requirements for optional group formation. Exp Econ 18(3):522–541

Siegel S, Castellan NJ Jr (1998) Nonparametric statistics for the behavioral sciences. McGraw-Hill, New York

Tiebout CM (1956) A pure theory of local expenditures. J Political Econ 64:416–424

Acknowledgements

This project was supported by a grant from the Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST) in Taiwan (MOST 106-2410-H-305-009-MY2). The author thanks the editor and two anonymous referees for very helpful comments and suggestions. The author also thanks Yi-Hsuan Fan for help in running the experiments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

About this article

Cite this article

Peng, HC. An experimental study on voluntary vs. compulsory provision of public goods under the vote-with-feet mechanism. Evolut Inst Econ Rev 18, 1–19 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40844-020-00192-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40844-020-00192-z