Abstract

Background

The sequences of several important mitochondrion-encoded genes involved in respiration in higher plants are interrupted by introns. Many nuclear-encoded factors are involved in splicing these introns, but the mechanisms underlying this splicing remain unknown.

Results

We isolated and characterized a rice mutant named floury shrunken endosperm 5 (fse5). In addition to having floury shrunken endosperm, the fse5 seeds either failed to germinate or produced seedlings which grew slowly and died ultimately. Fse5 encodes a putative plant organelle RNA recognition (PORR) protein targeted to mitochondria. Mutation of Fse5 hindered the splicing of the first intron of nad4, which encodes an essential subunit of mitochondrial NADH dehydrogenase complex I. The assembly and NADH dehydrogenase activity of complex I were subsequently disrupted by this mutation, and the structure of the mitochondria was abnormal in the fse5 mutant. The FSE5 protein was shown to interact with mitochondrial intron splicing factor 68 (MISF68), which is also a splicing factor for nad4 intron 1 identified previously via yeast two-hybrid (Y2H) assays.

Conclusion

Fse5 which encodes a PORR domain-containing protein, is essential for the splicing of nad4 intron 1, and loss of Fse5 function affects seed development and seedling growth.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

According to endosymbiotic theory, mitochondria originated from α-proteobacteria ancestors (Gray 1999). Throughout the long-term evolutionary history, most mitochondrial genes have been transferred to the nuclei of their host cells (Timmis et al. 2004). Only a minor portion of mitochondrial genes are retained in angiosperms, and those genes are involved in the electron transport system or encode ribosomal proteins and tRNAs (Kubo and Newton 2008). After these mitochondrial genes are transcribed, their transcripts are processed mainly by nuclear-encoded proteins. This posttranscriptional processing generally includes intron splicing, RNA editing, cleavage, and maturation (Small et al. 2013; Hammani and Giegé 2014).

According to their structural features and splicing mechanisms, mitochondrial introns in flowering plants can be divided into group I members and group II members, with the latter being more predominant (Bonen 2008). Group II introns are involved in both cis-splicing and trans-splicing. Cis-splicing occurs within one pre-mRNA molecule, whereas trans-splicing occurs between two pre-mRNA molecules (Sharp 1987; Lasda and Blumenthal 2011).

Various nuclear-encoded proteins are involved in splicing mitochondrial introns in higher plants. Among them, pentatricopeptide repeat (PPR) proteins such as AtMISF26 (Wang et al. 2018), ZmDEK35 (Chen et al. 2017), ZmDEK41/43 (Zhu et al. 2019; Ren et al. 2020), ZmEMP8 (Sun et al. 2018), ZmEMP602 (Ren et al. 2019) and OsFLO10 (Wu et al. 2019) are the most studied splicing factors (Small and Peeters 2000). Other proteins also participate in splicing mitochondrial introns, including the following: the DEXH-box-containing RNA helicases AtABO6 and AtPMH2 (Köhler et al. 2010; He et al. 2012); nuclear-encoded maturases nMAT1 (Nakagawa and Sakurai 2006; Keren et al. 2012), nMAT2 (Keren et al. 2009), and nMAT4 (Cohen et al. 2014); RCC1 family protein RUG3 (Kühn et al. 2011); mitochondrial transcription termination factor mTERF15 (Hsu et al. 2014); and RAD52-like protein ODB1 (Gualberto et al. 2015).

Members of another protein family characterized by their possession of the plant organelle RNA recognition (PORR) domain play an important role in intron splicing in plant organelles. The PORR domain was previously referred to as the “domain of unknown function 860” (DUF860) (http://pfam.xfam.org/family/PF11955) but was later renamed the PORR domain (Kroeger et al. 2009).

To date, several PORR domain-containing proteins have been identified in plants. AtRPD1, a member of the PORR/DUF860 family, has a role in prearranging the maintenance of active cell proliferation during root primordium development. Disruption of the ROOT PRIMORDIUM DEFECTIVE 1 (RPD1) gene causes embryogenesis arrest at the globular to transition stages. In silico structural characterization of RPD1 and RPD1-like proteins implied their possible involvement in various regulatory functions through DNA binding, RNA binding, and protein-protein interactions (Konishi and Sugiyama 2006). At4g08940, which encodes a PORR domain-containing protein, is expressed in response to oxidative stress. Compared with wild-type (WT) plants, transgenic At4g08940-overexpressing plants were more tolerant to paraquat and cold and less tolerant to t-butyl hydroperoxide and salinity (Luhua et al. 2008). AtWTF9, a mitochondrion-localized PORR domain-containing protein, is required for splicing introns in ribosomal protein L2 (rpl2) and cytochrome c biogenesis FC (ccmFC). T-DNA insertion alleles wtf9–1 and wtf9–2 caused severely stunted shoots and roots; both homozygous mutants were shown to survive to flowering, but the flowers were small and produced only a few milky aborted seeds (Colas des Francs-Small et al. 2012). A recent study showed that mitochondrial HSP60s interact together with WTF9 to regulate intron splicing of ccmFC and rpl2 (Hsu et al. 2019).

ZmWTF1, a chloroplast-targeted PORR domain-containing protein, is required for splicing chloroplast-encoded introns. wtf1–1, a relatively weak mutant, exhibited a pale green phenotype, whereas mutants wtf1–3 and wtf1–4 with null alleles were albino (Kroeger et al. 2009). ZmEMP6, a PORR domain-containing protein located in the mitochondria, is required for both endosperm and embryo development, but the target intron is unclear (Chettoor et al. 2015). To date, no PORR domain-containing protein has been identified in rice.

Here, we report the isolation of Fse5 in rice though map-based cloning. The Fse5 allele encodes a mitochondrion-targeted PORR domain-containing protein that is expressed constitutively in various tissues. Cis-splicing of nad4 intron 1 is abolished in the fse5 mutant, and mitochondrial function and structure are consequently disrupted. Like in other mutants whose mutations cause defective splicing of mitochondrial intron(s), fse5 seed development and seedling growth were affected. Mature fse5 seeds exhibited a floury, shrunken phenotype and either failed to germinate or produced weak seedlings that died within 1 month. Taken together, these results indicated that Fse5 plays an essential role in seed development and subsequent seedling growth.

Results

fse5 Seeds Have a Floury, Shrunken Phenotype

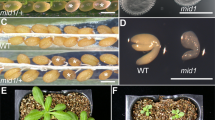

An N-methyl-N-nitrosourea (MNU)-treated population of WT japonica cultivar (cv) W017 was generated to study rice endosperm development. A mutant with floury, shrunken endosperm was selected and named floury shrunken endosperm 5 (fse5) (Fig. 1a-d). In addition to the abnormal phenotype, the seeds of the fse5 mutants failed to germinate or produced seedlings which grew slowly and died within 1 month. Homozygous fse5 seeds are presumably reproduced by heterozygous plants (+/fse5) whose progenies have approximately one-quarter seeds with a mutant phenotype (Additional file 1: Figure S1 and Table S1). Compared with those of the WT W017 seeds, both the 1000-grain weight and grain thickness of mature fse5 seeds were significantly reduced, but there was no difference in grain length or grain width (Additional file 1: Figure S2A-S2D). In the fse5 mutant, seed starch and amylose contents were lower (Additional file 1: Figure S2E-S2F), whereas the protein and lipid contents were higher than in the WT (Additional file 1: Figure S2G-S2H). These data showed that the synthesis of seed storage products, especially starch, was significantly affected in fse5 seeds.

Phenotypes of mature and developing seeds of the WT and fse5 mutant. a and b Mature WT (a) and fse5 (b) seeds. Bars, 1 mm. c and d Transverse sections of mature WT (c) and fse5 (d) seeds. Bars, 0.5 mm. e-h Scanning electron microscopy of transverse sections of mature WT (e, g) and fse5 (f, h) seeds. Bars, 100 μm in (e) and (f); 10 μm in (g) and (h). i-l Iodine-stained semithin endosperm sections of wt (i, k) and fse5 (j, l) seeds at 12 DAF. Bars, 15 μm in (i) and (j); 7.5 μm in (k) and (l)

To evaluate defects at the cellular level, observations were made on mature and immature endosperm cells of the WT and fse5 seeds. Scanning electron microscopy showed that starch grains of mature fse5 seeds were smooth and loosely packed, whereas those of WT seeds had sharp edges and were tightly assembled (Fig. 1e-h). Compared with those in the WT seeds, starch grains in the fse5 seeds were irregular and loosely assembled in the developing endosperm cells (Fig. 1i-l). Taken together, these data indicated that the fse5 mutation affected starch grain development.

The fse5 Mutation Causes Embryo and Seedling Death

Detailed examination of the germination of the mutant and WT seeds showed that fse5 seeds with hulls could not germinate, so dehulled seeds were used in further experiments. Compared with that of the WT seeds, the germination percentage of the fse5 seeds was significantly lower (Additional file 1: Figure S2I), and the plumules and radicles of the latter grew more slowly (Fig. 2a-b). Compared with 94.0% of the WT seeds, only 35.7% of the mutant seeds had produced seedlings by 9 days after sowing (DAS) in the soil (Additional file 1: Figure S2J). The height of fse5 seedlings reached only one-fourth of that of the WT seedlings (Fig. 2c, Additional file 1: Figure S2K). Moreover, all the fse5 seedlings were dead by 30 DAS (Fig. 2d). Taken together, these data showed that the fse5 mutants exhibited seed- or seedling-lethal phenotypes.

Seed germination and seedling phenotypes. A and B, Germinating seedlings of WT (a) and fse5 mutants (b) at 3 DAS. Bars, 5 mm. c and d Seedlings grown from WT (left) and fse5 (right) seeds at 9 DAS (c) and 30 DAS (d). Bars, 5 cm in (c) and 10 cm in (d). e and f Longitudinal sections of mature WT (e) and fse5 (f) seeds after 24 h of imbibition. Bars, 1 mm. g and h TTC staining of WT (g) and fse5 (h) seeds. The black arrows indicate embryos after staining. Bars, 1 cm

To determine the cause of seed or seedling lethality, the embryo structures were observed. Longitudinal sections of seeds after 24 h of imbibition with water revealed clear differentiation in the WT embryos but little change in the fse5 mutant embryos (Fig. 2e-f). Triphenyl tetrazolium chloride (TTC) staining indicated strong red staining of the WT embryo region, indicating active dehydrogenase activity (Brown et al. 1987), but comparatively little staining of the same tissues in fse5 seeds (Fig. 2g-h). These results indicated defective embryo differentiation and low seed vigor in the mutant.

Positional Cloning of Fse5

An F2 population originating from a cross between a heterozygous (+/fse5) plant and Nanjing 11 (indica) was used to map the Fse5 locus. Based on the data from 92 F2 individuals, the locus was mapped to a 7.2 cM region flanked by RM242 and RM257 on the long arm of chromosome 9. Nine hundred and seventy-eight F2 individuals were used to further delimit the Fse5 locus to a 54 kb region between insertion/deletion (In/Del) markers wi-10 and wi-11. Nine open reading frames (ORFs) were predicted in this region (Fig. 3a) (http://rice.plantbiology.msu.edu). Sequence analysis revealed a 408 bp deletion in LOC_Os09g29760 in the fse5 mutant compared with the WT. The deletion caused a truncation of 136 amino acids (aa) in the fse5 mutant transcript (Fig. 3b). Thus, LOC_Os09g29760 was considered to be the candidate gene for Fse5.

Positional cloning of the Fse5 locus. a The Fse5 locus was restricted to a 54 kb region flanked by markers wi-10 and wi-11 on chromosome 9 (Chr. 9) and included nine ORFs. Both markers and numbers of recombinants are shown. b Mutation site in LOC_Os09g29760 in the fse5 mutant. A deleted 408 bp fragment near the end of the exon leads to a 136 aa truncation in the putative encoded protein in the fse5 mutant. The red letters and dotted lines represent the deletion in LOC_Os09g29760 or its encoded protein in the fse5 mutant. The yellow and orange boxes indicate the 5′ untranslated region (UTR) and single exon of LOC_Os09g29760, respectively. c Expression of LOC_Os09g29760 in WT, fse5 mutant and complemented (COM) lines. The primer pair designed within the 408 bp deletion was used in qRT-PCR. Three biological replicates were subjected to qRT-PCR. OsActin1 was used as an internal control for data normalization. The values are the means ± SDs. ND, not detected. d Phenotypes of seeds (upper panel) and transverse sections (lower panel) of WT, fse5 mutant and COM seeds. Bars, 1 mm. e Nine-day-old seedlings of WT, fse5 mutant and COM lines. Bar, 5 cm

To further confirm these results, a vector containing the native promoter and WT coding DNA sequence (CDS) of LOC_Os09g29760 was constructed and introduced into the fse5 mutant. Quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) showed that the expression level of LOC_Os09g29760 was rescued in the positive transgenic lines (Fig. 3c). The dehulled seeds of these lines were transparent and plump, similar to those of the WT (Fig. 3d). Moreover, seedlings grown from these seeds exhibited normal phenotypes (Fig. 3e). Further validation was acquired from LOC_Os09g29760 knockout (KO) lines produced by CRISPR/Cas9 (Additional file 1: Figure S3A-S3B). The dehulled seeds from four independent KO lines segregated for both normal and mutant seeds in a pattern similar to that of the original mutant (Additional file 1: Figure S3C). Therefore, LOC_Os09g29760 was demonstrated to be the Fse5 allele.

Fse5 Encodes a PORR Domain-Containing Protein

Sequence analysis showed that the cloned Fse5 allele contains a single exon (Fig. 4a) and encodes a putative protein of 399 aa (http://rice.plantbiology.msu.edu). The protein was annotated as containing a PORR domain (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov; https://ricexpro.dna.affrc.go.jp), and the truncation of 136 aa encoded by the 408 bp fragment deleted in the fse5 allele was within this domain (Fig. 4b). FSE5 was named OsPORR1 because it was the first PORR domain-containing protein identified among the 17 putative PORR domain-containing proteins in rice (Kroeger et al. 2009; Colas des Francs-Small et al. 2012; Chettoor et al. 2015) (Fig. 4c). Multiple sequence alignment showed that 6 aa (Leu172, Glu305, Leu307, Phe344, Tyr345, and Leu357) are highly conserved among all 17 members of the rice family of PORR domain-containing proteins, and all six aa are within the PORR domain, suggesting that they are essential for the function of PORR domain-containing proteins (Fig. 4d). Five of these aa (Leu172 is excluded) are present within the truncated 136 aa (Fig. 4b) and therefore likely affect the function of OsPORR1.

OsPORR1 domain and its phylogenetic analysis. a Representation of the deleted 408 bp fragment in the 664–1071 bp region of the OsPORR1 CDS. b The PORR domain is the 65–385 amino acid region of the OsPORR1 sequence. The deleted 136 amino acid fragment is in the region from 222 to 357 aa, within the PORR domain. M, methionine. c Phylogenetic analysis of all PORR family members in rice. The black asterisk indicates OsPORR1. d Multiple sequence alignment of 17 rice PORR domain-containing proteins. The numbers over arrows represent the positions of six highly conserved aa (Leu172, Glu305, Leu307, Phe344, Tyr345, and Leu357)

The orthologs of OsPORR1 in maize and Arabidopsis are GRMZM2G048392 (ZmEmp6) and At4g08940, respectively (Kroeger et al. 2009; Chettoor et al. 2015). The mutation of ZmEmp6 causes early arrest in grain development, and compared with WT plants, At4g08940-overexpressing transgenic plants are more tolerant to paraquat and cold and less tolerant to t-butyl hydroperoxide and salinity (Luhua et al. 2008; Chettoor et al. 2015). However, the mechanisms underlying these effects remain unknown.

Spatiotemporal Expression and Subcellular Localization of OsPORR1

qRT-PCR analysis showed that OsPORR1 was expressed in the roots, stems, leaves, leaf sheaths, panicles, developing seeds and seedlings according to the multiple phenotypic characteristics of the fse5 mutant (Fig. 5a). A vector construct containing the β-glucuronidase (GUS) reporter gene driven by the OsPORR1 promoter was transformed into rice cv Nipponbare (japonica) to confirm the expression of OsPORR1; GUS staining was observed in the abovementioned tissues (Additional file 1: Figure S4). Both experiments suggested that OsPORR1 was constitutively expressed in different tissues and at different growth stages.

Spatiotemporal expression and subcellular localization of OsPORR1. a Expression of OsPORR1 in various plant organs, developing seeds and seedlings at different times. DAG, days after germination. Three biological replicates were subjected to qRT-PCR. OsActin1 was used as an internal control for data normalization. The values are the means ± SDs. b Subcellular localization of OsPORR1. GFP served as a control. GFP signals in protoplasts isolated from positive transgenic seedlings were observed via confocal laser scanning microscopy. Mito Tracker Orange was used to identify mitochondria. Bars, 10 μm

OsPORR1 was predicted to localize to the mitochondria based on TargetP analysis (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/TargetP). A vector construct in which a green fluorescent protein (GFP) was fused to the full-length OsPORR1 sequence was transformed into rice cv Nipponbare. The GFP signals in protoplasts isolated from positive transgenic seedlings showed a punctate pattern that overlapped with the orange fluorescence of the mitochondrial indicator Mito Tracker Orange (Fig. 5b). Taken together, these data showed that OsPORR1 was a mitochondrion-targeted protein.

OsPORR1 Functions in Splicing Mitochondrial nad4 Intron 1

Previous studies have shown that PORR domain-containing proteins usually function in intron splicing of chloroplast- or mitochondrion-encoded genes (Kroeger et al. 2009; Colas des Francs-Small et al. 2012). Based on this premise and their subcellular localization, transcripts of 9 mitochondrion-encoded genes with introns were analyzed. The results showed an absence of the mature nad4 transcript in the fse5 mutant, but the mutant had a larger nad4 transcript than the WT did (Fig. 6a). These results suggested that an intron-splicing defect of nad4 had occurred in the fse5 mutant. To further confirm the nonspliced intron, each intron of nad4 was amplified by specific primers in the WT and fse5 mutant. The results indicated that the splicing of nad4 intron 1 was abolished and that no mature nad4 transcript was detected in the fse5 mutant (Fig. 6b). All mitochondrial introns in rice were examined via qRT-PCR in conjunction with two groups of specific primers. One group was used to amplify the spliced introns, whereas the other group was used for nonspliced introns. Only nad4 exon 1-exon 2 (spliced fragment) was not detected (ND) in the fse5 mutant, although its precursor fragment was present (Additional file 1: Figure S5). These data indicated that OsPORR1 specifically affected the splicing of nad4 intron 1.

Splicing of nad4 intron 1 was abolished in the fse5 mutant. Total RNA was extracted from nine-day-old seedlings, and random hexamer primers were used to synthetize first-strand cDNA. a, Transcript analysis of mitochondrial intron-containing genes in the WT (left) and fse5 mutant (right). OsActin1 was used as the internal control. Specific primers were used to amplify 9 transcripts (Wu et al. 2019). b, Schematic of nad4 precursor mRNA and RT-PCR analysis of three introns of nad4. nad4 precursor mRNA consists of 4 exons (E1-E4) and 3 introns. The black boxes indicate exons, and the curved lines represent introns. a, b, c, and m are fragments amplified by exon-exon flanking primers (Chen et al. 2017). Numbers of nucleic acids included by the introns and fragments are noted. M, DNA marker

Mutation in OsPORR1 Affects Mitochondrial Structure and Function

Nad4 is an important subunit of complex I in the electron transfer chain of mitochondria. Complex I assembly and activity in seedlings were analyzed by blue native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (BN-PAGE). The results showed that the accumulation of complex I in the fse5 mutant was much lower than that in the WT, and NADH dehydrogenase activity was almost completely abolished (Fig. 7a). The ATP content and respiration rate were also reduced in the mutant compared with the WT (Fig. 7b-c). Complex I is an important component of the mitochondrial inner membrane. Observations were made of the mitochondrial inner structure in developing endosperm cells of the WT and fse5 mutant. The inner envelope cristae of mitochondria were well organized and surrounded by a dense stroma in the WT, whereas cristae development was poor and the stroma was thin in the fse5 mutant (Fig. 7d). Previous studies have shown that compromises to the main respiratory chain cause changes in the expression levels of alternative oxidase (AOX)- and NADH dehydrogenase-encoding genes (Toda et al. 2012; Li et al. 2013). Therefore, the transcript levels of AOX-encoding genes (OsAOX1a, OsAOX1b and OsAOX1c) and alternative NADH dehydrogenase-encoding genes (OsNDA1, OsNDA2, OsNDB1, OsNDB2, OsNDB3, and OsNDC1) were measured via by qRT-PCR. The expression of OsAOX1a, OsNDB2 and OsNDB3 was higher in the fse5 mutant than in the WT, but there were no differences in expression of the other genes (Fig. 7e). Taken together, these data showed that the defective splicing of nad4 intron 1 was associated with changes in mitochondrial structure and function.

Mitochondrial function and structure were disrupted in fse5 mutant cells. a Mitochondrial complexes separated by BN-PAGE and stained with Coomassie brilliant blue (CBB) (left) and in-gel NADH dehydrogenase activity of complex I (arrow) (right). b and c Measurement of ATP contents (b) and respiration rates (c). The values are the means ± SDs. **, P < 0.01, Student’s t test. d Mitochondria in developing endosperm cells of the WT and fse5 seeds at 9 DAF. Bars, 0.5 μm. e Expression of AOX-encoding genes (AOX1a, AOX1b and AOX1c) and alternative NADH dehydrogenase-encoding genes (NDA1, NDA2, NDB1, NDB2, NDB3, and NDC1) in nine-day-old seedlings. Specific primers were used for qRT-PCR (Toda et al. 2012; Li et al. 2013). The data are based on three biological replicates. OsActin1 was used as an internal control for data normalization. The values are the means ± SDs

Discussion

The fse5 mutant was isolated via artificial mutagenesis. Like that of other floury endosperm mutants such as floury endosperm2 (flo2) (She et al. 2010), flo4 (Kang et al. 2005), flo6 (Peng et al. 2014), flo7 (Zhang et al. 2016), flo10 (Wu et al. 2019), flo11 (Zhu et al. 2018), flo15 (You et al. 2019), and flo16 (Teng et al. 2019), the endosperm of fse5 seeds has loosely packed starch grains. Total starch and amylose contents (Additional file 1: Figure S2E-S2F) and accumulations of major starch synthases granule-bound starch synthase I (GBSSI), starch synthase IIa (SSIIa), starch branching enzyme I (SBEI), and SBEIIb (Additional file 1: Figure S6) were reduced in the fse5 seeds compared with the WT W017 seeds. Unlike most other floury endosperm mutants, the fse5 mutant was embryo- or seedling- lethal. OsPORR1 is involved in the splicing of nad4 intron 1, which is indispensable for normal mitochondrial structure and function. Defects in the splicing of mitochondrion-encoded introns, especially in NADH dehydrogenase subunit (nad) genes, usually cause aborted seeds, slow-growing seedlings or small plants (Falcon de Longevialle et al. 2007; Koprivova et al. 2010; Liu et al. 2010; Colas des Francs-Small et al. 2014; Yang et al. 2014; Hsieh et al. 2015; Haïli et al. 2016; Xiu et al. 2016; Cai et al. 2017; Chen et al. 2017; Qi et al. 2017; Ren et al. 2017; Dai et al. 2018; Sun et al. 2018; Sun et al. 2019; Wang et al. 2018; Ren et al. 2019; Wu et al. 2019; Zhu et al. 2019; Ren et al. 2020; Yang et al. 2020).

Emp6, an ortholog of OsPORR1 in maize, is also located in mitochondria. Mutant emp6 kernels show obvious defects in embryos and throughout the endosperm, similar to those of the fse5 mutant seeds (Chettoor et al. 2015); thus, ZmEMP6 probably functions in grain development in a manner similar to OsFSE5. Multiple sequence alignment showed that the sequences of the PORR domain in ZmWTF1 and AtWTF9 were 49.24% and 38.23% similar, respectively, to that of OsPORR1 (Additional file 1: Figure S7). Both ZmWTF1 and its PORR domain have RNA-binding activity, and ZmWTF1 promotes the splicing of multiple group II introns in chloroplasts (Kroeger et al. 2009). AtWTF9 can also bind RNA and is required for splicing introns of rpl2 and ccmFC in mitochondria (Colas des Francs-Small et al. 2012). OsPORR1 is probably involved in the splicing of nad4 intron 1 by binding to RNA fragments.

Nad4 is an essential subunit of complex I in the mitochondrial respiratory chain. The splicing of nad4 intron 1 is required for mitochondrial function. Like OsPORR1, ZmDEK35, a mitochondrion-targeted PPR protein, is especially essential for the splicing of nad4 intron 1. A mutation in Dek35 affected mitochondrial complex I assembly and NADH dehydrogenase activity, and the dek35 mutant displayed defective seed development similar to that of the fse5 mutant (Chen et al. 2017). Intriguingly, small subcomplexes generally considered to be intermediates of complex I were observed by BN-PAGE of the dek35 mutant but not the fse5 mutant (Li et al. 2014). A possible explanation is that different tissues of maize and rice were used for BN-PAGE. Homozygous immature dek35 kernels were used to extract crude mitochondria for BN-PAGE, whereas homozygous seedlings or calli (−/−) are usually used in the case of rice (Hao et al. 2019; Wu et al. 2019; Zheng et al. 2021). In this study, homozygous fse5 seedlings were used for BN-PAGE. Homozygous immature dek35 kernels (−/−) are born on heterozygous maternal tissues (+/−) and can acquire maternal nutrients and energy. In those kernels, the defective splicing of nad4 intron 1 led to dramatically decreased complex I (Chen et al. 2017). The accumulation of subcomplexes may be a response to decreased complex I under coregulation of maternal tissues and mutational kernels. Without support from heterozygous maternal tissues, the response in homozygous seedlings or calli is perhaps weakened or abolished. Thus, small subcomplexes were not observed in the fse5 mutant or rice ppr mutants such as fgr1, flo10 and osppr939 (Hao et al. 2019; Wu et al. 2019; Zheng et al. 2021).

In addition to ZmDEK35, other PPR proteins such as AtMISF68 (Wang et al. 2018), ZmEMP8 (Sun et al. 2018), ZmEMP602 (Ren et al. 2019) and ZmDEK43 (Ren et al. 2020), and the DEXH-box RNA helicase AtABO6 (He et al. 2012) also affect the splicing of nad4 intron 1. Their rice orthologs were identified by phylogenetic analysis and subjected to Y2H assays to verify interactions between them. The results of our Y2H assays showed that OsMISF68 interacted together with OsABO6, OsDEK35, OsDEK43, OsEMP8, OsPORR1 and itself (Additional file 1: Figure S8), suggesting a possible functional coordination among these proteins. Whether and how these factors synchronously regulate the splicing of nad4 intron 1 have yet to be determined.

Conclusions

Fse5 encodes a PORR domain-containing protein involved in the splicing of nad4 intron 1, which is indispensable for normal mitochondrial structure and function. Abnormal mitochondrial cristae and a reduced respiration rate in the fse5 mutant led to a lower ATP content compared with that in the WT and ultimately affected seed development and viability. These results provide valuable clues for revealing the roles of PORR domain-containing proteins in rice seed development and seedling growth.

Materials and Methods

Plant Materials and Growth Conditions

The fse5 mutant was isolated from an MNU-mutagenized population of W017, a japonica variety whose seeds have excellent taste and texture. An F2 population for gene mapping was generated by a cross between a heterozygous plant (+/fse5) and indica cv Nanjing 11. Seed germination tests and seedling growth were subsequently carried out in a growth chamber (12 h light/12 h darkness at 30 °C). Other materials were grown in a paddy field.

Microscopy

Transverse sections of mature seeds were observed via a Hitachi S-3400 N scanning electron microscope (http://www.hitachi-hitec.com). Scanning electron microscopy was performed as described previously (Kang et al. 2005). Semithin sections of developing seeds at 12 days after flowering (DAF) were observed via light microscope, and sample fixation and sectioning were performed as described previously (Peng et al. 2014).

Map-Based Cloning of OsPORR1

OsPORR1 was initially mapped using more than 160 polymorphic simple sequence repeat (SSR) and In/Del markers to genotype a small number of mutant F2 individuals produced from the abovementioned cross. Fine mapping was then performed with tightly linked molecular markers designed from nucleotide polymorphisms between the Nipponbare and 93–11 reference genomes. The molecular markers used for fine mapping are listed in Additional file 1: Table S2.

Genetic Complementation

A vector containing the full-length cDNA sequence of OsPORR1 driven by its native promoter was constructed (the primers used are listed in Additional file 1: Table S3) and transformed into the fse5 mutant via Agrobacterium tumefaciens. Positive transgenic plants were identified by the hygromycin resistance gene used as the selective marker in the pCUbi1390 vector.

RNA Extraction, Reverse Transcription PCR (RT-PCR) and qRT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from various tissues using an RNA Prep Pure Plant kit (Tiangen Co., Beijing; http://www.tiangen.com/en/). First-strand cDNA was synthesized using random hexamer primers for mitochondrion-encoded genes and oligo (dT) for nuclear-encoded genes, and PrimeScript Reverse Transcriptase (TaKaRa; http://www.takara-bio.com) was used for reverse transcription. OsActin1 (Os03g0718150) was used as an internal control (Peng et al. 2014). qRT-PCR was performed and the results were analyzed by an ABI 7500 real-time system. The primers used in RT-PCR for nine mitochondrion-encoded genes with introns and for three introns of nad4 are listed in Additional file 1: Table S4, and the primers used in qRT-PCR for OsPORR1, AOX- and alternative NADH dehydrogenase-encoding genes, introns and corresponding exons of mitochondrion-encoded genes are listed in Additional file 1: Table S5.

Subcellular Localization

The coding region of OsPORR1 was cloned and inserted in a pCAMBIA1305-GFP vector (the primers used are listed in Additional file 1: Table S3), after which the vector was introduced into rice cv Nipponbare via Agrobacterium tumefaciens. Protoplasts of positive seedlings were isolated as described previously (Chen et al. 2006). GFP fluorescent signals were detected by confocal laser scanning microscopy (Leica SP8), and Mito Tracker Orange CMTMRos (Invitrogen, Shanghai) was used to mark the mitochondria.

BN-PAGE and Complex I Activity Assays

Crude mitochondria were extracted from ten-day-old seedlings grown at 30 °C in darkness (Wang et al. 2017; Wu et al. 2019). BN-PAGE and complex I activity assays were then performed as described previously (Wittig et al. 2006; Hao et al. 2019; Wu et al. 2019).

Measurement of ATP Content and Respiration Rate

The ATP content of twelve-day-old seedlings grown at 30 °C in darkness was measured with an ATP assay kit (Beyotime, Shanghai), and the respiration rate of nine-day-old seedlings grown at 30 °C was measured by a liquid-phase oxygen electrode (Hansatech, UK).

Availability of Data and Materials

All data supporting the conclusions of this article are provided within the article (and its additional files).

Abbreviations

- ABO:

-

ABA OVERLY SENSITIVE

- AGPL2:

-

ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase large subunit 2

- AGPS2b:

-

ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase small subunit 2b

- AOX:

-

Alternative oxidase

- BN-PAGE:

-

Blue native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

- CBB:

-

Coomassie brilliant blue

- ccmF C :

-

Cytochrome c biogenesis F C

- CDS:

-

Coding DNA sequence

- COM:

-

Complemented

- cox2 :

-

Cytochrome c oxidase subunit II

- cv:

-

Cultivar

- DAF:

-

Days after flowering

- DAG:

-

Days after germination

- DAS:

-

Days after sowing

- DEK:

-

Defective kernel

- EF-1α:

-

Translation elongation factor 1α

- EMP:

-

Empty pericarp

- FLO:

-

Floury endosperm

- FSE5:

-

FLOURY SHRUNKEN ENDOSPERM 5

- GBSSI:

-

Granule-bound starch synthase I

- GFP:

-

Green fluorescent protein

- GUS:

-

β-glucuronidase

- HSP60:

-

Heat shock protein 60

- In/Del:

-

Insertion/Deletion

- KO:

-

Knockout

- MISF:

-

Mitochondrial intron splicing factor

- MNU:

-

N-methyl-N-nitrosourea

- nad :

-

NADH dehydrogenase subunit

- ND:

-

Not detected

- NDA:

-

Alternative NADH dehydrogenase A

- NDB:

-

Alternative NADH dehydrogenase B

- NDC:

-

Alternative NADH dehydrogenase C

- ORF:

-

Open reading frame

- PAM:

-

Protospacer-adjacent motif

- PORR:

-

Plant organelle RNA recognition

- PPR:

-

Pentatricopeptide repeat

- qRT-PCR:

-

Quantitative RT-PCR

- RPD1:

-

ROOT PRIMORDIUM DEFECTIVE 1

- rpl2 :

-

Ribosomal protein L2

- rps3 :

-

Ribosomal protein S3

- SBE:

-

Starch branching enzyme

- SSIIa:

-

Starch synthase IIa

- TTC:

-

Triphenyl tetrazolium chloride

- UTR:

-

Untranslated region

- WT:

-

Wild type

- WTF:

-

What’s this factor

- Y2H:

-

Yeast two-hybrid assay

References

Bonen L (2008) Cis- and trans-splicing of group II introns in plant mitochondria. Mitochondrion 8:26–34

Brown P, Welch R, Cary E (1987) Nickel: a micronutrient essential for higher plants. Plant Physiol 85:801–803

Cai M, Li S, Sun F, Sun Q, Zhao H, Ren X, Zhao Y, Tan B, Zhang Z, Qiu F (2017) Emp10 encodes a mitochondrial PPR protein that affects the cis-splicing of nad2 intron 1 and seed development in maize. Plant J 91:132–144

Chen S, Tao L, Zeng L, Vega-Sanchez ME, Umemura K, Wang GL (2006) A highly efficient transient protoplast system for analyzing defence gene expression and protein-protein interactions in rice. Mol Plant Pathol 7:417–427

Chen X, Feng F, Qi W, Xu L, Yao D, Wang Q, Song R (2017) Dek35 encodes a PPR protein that affects cis-splicing of mitochondrial nad4 intron 1 and seed development in maize. Mol Plant 10:427–441

Chettoor AM, Yi G, Gomez E, Hueros G, Meeley RB, Becraft PW (2015) A putative plant organelle RNA recognition protein gene is essential for maize kernel development. J Integr Plant Biol 57:236–246

Cohen S, Zmudjak M, Colas d, Francs Small C, Malik S, Shaya F, Keren I, Belausov E, Many Y, Brown GG, Small I, Ostersetzer-Biran O (2014) nMAT4, a maturase factor required for nad1 pre-mRNA processing and maturation, is essential for holocomplex I biogenesis in Arabidopsis mitochondria. Plant J 78:253–268

Colas des Francs-Small C, Falcon de Longevialle A, Li Y, Lowe E, Tanz SK, Smith C, Bevan MW, Small I (2014) The pentatricopeptide repeat proteins TANG2 and ORGANELLE TRANSCRIPT PROCESSING439 are involved in the splicing of the multipartite nad5 transcript encoding a subunit of mitochondrial complex I. Plant Physiol 165:1409–1416

Colas des Francs-Small C, Kroeger T, Zmudjak M, Ostersetzer-Biran O, Rahimi N, Small I, Barkan A (2012) A PORR domain protein required for rpl2 and ccmFC intron splicing and for the biogenesis of c-type cytochromes in Arabidopsis mitochondria. Plant J 69:996–1005

Dai D, Luan S, Chen X, Wang Q, Feng Y, Zhu C, Qi W, Song R (2018) Maize Dek37 encodes a P-type PPR protein that affects cis-splicing of mitochondrial nad2 intron 1 and seed development. Genetics 208:1069–1082

Falcon de Longevialle A, Meyer EH, Andrés C, Taylor NL, Lurin C, Millar AH, Small ID (2007) The pentatricopeptide repeat gene OTP43 is required for trans-splicing of the mitochondrial nad1 intron 1 in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell 19:3256–3265

Gray MW (1999) Evolution of organellar genomes. Curr Opin Genet Dev 9:678–687

Gualberto JM, Le Ret M, Beator B, Kühn K (2015) The RAD52-like protein ODB1 is required for the efficient excision of two mitochondrial introns spliced via first-step hydrolysis. Nucleic Acids Res 43:6500–6510

Haïli N, Planchard N, Arnal N, Quadrado M, Vrielynck N, Dahan J, Colas d, Francs-Small C, Mireau H (2016) The MTL1 pentatricopeptide repeat protein is required for both translation and splicing of the mitochondrial NADH DEHYDROGENASE SUBUNIT7 mRNA in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 170:354–366

Hammani K, Giegé P (2014) RNA metabolism in plant mitochondria. Trends Plant Sci 19:380–389

Hao Y, Wang Y, Wu M, Zhu X, Teng X, Sun Y, Zhu J, Zhang Y, Jing R, Lei J, Li J, Bao X, Wang C, Wang Y, Wan J (2019) The nuclear-localized PPR protein OsNPPR1 is important for mitochondrial function and endosperm development in rice. J Exp Bot 70:4705–4720

He J, Duan Y, Hua D, Fan G, Wang L, Liu Y, Chen Z, Han L, Qu LJ, Gong Z (2012) DEXH box RNA helicase-mediated mitochondrial reactive oxygen species production in Arabidopsis mediates crosstalk between abscisic acid and auxin signaling. Plant Cell 24:1815–1833

Hsieh WY, Liao JC, Chang CY, Harrison T, Boucher C, Hsieh MH (2015) The SLOW GROWTH3 pentatricopeptide repeat protein is required for the splicing of mitochondrial NADH dehydrogenase subunit7 intron 2 in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 168:490–501

Hsu YW, Juan CT, Wang CM, Jauh GY (2019) Mitochondrial heat shock protein 60s interact with what’s this factor 9 to regulate RNA splicing of ccmFC and rpl2. Plant Cell Physiol 60:116–125

Hsu YW, Wang HJ, Hsieh MH, Hsieh HL, Jauh GY (2014) Arabidopsis mTERF15 is required for mitochondrial nad2 intron 3 splicing and functional complex I activity. PLoS One 9:e112360

Kang HG, Park S, Matsuoka M, An G (2005) White-core endosperm floury endosperm-4 in rice is generated by knockout mutations in the C4-type pyruvate orthophosphate dikinase gene (OsPPDKB). Plant J 42:901–911

Keren I, Bezawork-Geleta A, Kolton M, Maayan I, Belausov E, Levy M, Mett A, Gidoni D, Shaya F, Ostersetzer-Biran O (2009) AtnMat2, a nuclear-encoded maturase required for splicing of group-II introns in Arabidopsis mitochondria. RNA 15:2299–2311

Keren I, Tal L, Colas d, Francs-Small C, Araújo WL, Shevtsov S, Shaya F, Fernie AR, Small I, Ostersetzer-Biran O (2012) nMAT1, a nuclear-encoded maturase involved in the trans-splicing of nad1 intron 1, is essential for mitochondrial complex I assembly and function. Plant J 71:413–426

Köhler D, Schmidt-Gattung S, Binder S (2010) The DEAD-box protein PMH2 is required for efficient group II intron splicing in mitochondria of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Mol Biol 72:459–467

Konishi M, Sugiyama M (2006) A novel plant-specific family gene, ROOT PRIMORDIUM DEFECTIVE 1, is required for the maintenance of active cell proliferation. Plant Physiol 140:591–602

Koprivova A, Colas d, Francs-Small C, Calder G, Mugford ST, Tanz S, Lee BR, Zechmann B, Small I, Kopriva S (2010) Identification of a pentatricopeptide repeat protein implicated in splicing of intron 1 of mitochondrial nad7 transcripts. J Biol Chem 285:32192–32199

Kroeger TS, Watkins KP, Friso G, van Wijk KJ, Barkan A (2009) A plant-specific RNA-binding domain revealed through analysis of chloroplast group II intron splicing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106:4537–4542

Kubo T, Newton KJ (2008) Angiosperm mitochondrial genomes and mutations. Mitochondrion 8:5–14

Kühn K, Carrie C, Giraud E, Wang Y, Meyer EH, Narsai R, Colas d, Francs-Small C, Zhang B, Murcha MW, Whelan J (2011) The RCC1 family protein RUG3 is required for splicing of nad2 and complex I biogenesis in mitochondria of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J 67:1067–1080

Lasda EL, Blumenthal T (2011) Trans-splicing. Wiley Interdiscip Rev-RNA 2:417–434

Lee K, Han JH, Park YI, Colas d, Francs-Small C, Small I, Kang H (2017) The mitochondrial pentatricopeptide repeat protein PPR19 is involved in the stabilization of NADH dehydrogenase 1 transcripts and is crucial for mitochondrial function and Arabidopsis thaliana development. New Phytol 215:202–216

Li C, Liang D, Li J, Duan Y, Li H, Yang Y, Qin R, Li L, Wei P, Yang J (2013) Unravelling mitochondrial retrograde regulation in the abiotic stress induction of rice ALTERNATIVE OXIDASE 1 genes. Plant Cell Environ 36:775–788

Li X, Zhang Y, Hou M, Sun F, Shen Y, Xiu Z, Wang X, Chen Z, Sun SS, Small I, Tan B (2014) Small kernel 1 encodes a pentatricopeptide repeat protein required for mitochondrial nad7 transcript editing and seed development in maize (Zea mays) and rice (Oryza sativa). Plant J 79:797–809

Liu Y, He J, Chen Z, Ren X, Hong X, Gong Z (2010) ABA overly-sensitive 5 (ABO5), encoding a pentatricopeptide repeat protein required for cis-splicing of mitochondrial nad2 intron 3, is involved in the abscisic acid response in Arabidopsis. Plant J 63:749–765

Luhua S, Ciftci-Yilmaz S, Harper J, Cushman J, Mittler R (2008) Enhanced tolerance to oxidative stress in transgenic Arabidopsis plants expressing proteins of unknown function. Plant Physiol 148:280–292

Nakagawa N, Sakurai N (2006) A mutation in At-nMat1a, which encodes a nuclear gene having high similarity to group II intron maturase, causes impaired splicing of mitochondrial nad4 transcript and altered carbon metabolism in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol 47:772–783

Peng C, Wang Y, Liu F, Ren Y, Zhou K, Lv J, Zheng M, Zhao S, Zhang L, Wang C, Jiang L, Zhang X, Guo X, Bao Y, Wan J (2014) FLOURY ENDOSPERM6 encodes a CBM48 domain-containing protein involved in compound granule formation and starch synthesis in rice ENDOSPERM. Plant J 77:917–930

Qi W, Yang Y, Feng X, Zhang M, Song R (2017) Mitochondrial function and maize kernel development requires Dek2, a pentatricopeptide repeat protein involved in nad1 mRNA splicing. Genetics 205:239–249

Ren R, Wang L, Zhang L, Zhao Y, Wu J, Wei Y, Zhang X, Zhao X (2020) DEK43 is a P-type PPR protein responsible for the cis-splicing of nad4 in maize mitochondria. J Integr Plant Biol 62:299–313

Ren X, Pan Z, Zhao H, Zhao J, Cai M, Li J, Zhang Z, Qiu F (2017) EMPTY PERICARP11 serves as a factor for splicing of mitochondrial nad1 intron and is required to ensure proper seed development in maize. J Exp Bot 68:4571–4581

Ren Z, Fan K, Fang T, Zhang J, Yang L, Wang J, Wang G, Liu Y (2019) Maize Empty Pericarp602 encodes a P-type PPR protein that is essential for seed development. Plant Cell Physiol 60:1734–1746

Sharp PA (1987) Trans splicing: variation on a familiar theme ? Cell 50:147–148

She KC, Kusano H, Koizumi K, Yamakawa H, Hakata M, Imamura T, Fukuda M, Naito N, Tsurumaki Y, Yaeshima M, Tsuge T, Matsumoto K, Kudoh M, Itoh E, Kikuchi S, Kishimoto N, Yazaki J, Ando T, Yano M, Aoyama T, Sasaki T, Satoh H, Shimada H (2010) A novel factor FLOURY ENDOSPERM2 is involved in regulation of rice grain size and starch quality. Plant Cell 22:3280–3294

Small ID, Peeters N (2000) The PPR motif: a TPR-related motif prevalent in plant organellar proteins. Trends Biochem Sci 25:46–47

Small ID, Rackham O, Filipovska A (2013) Organelle transcriptomes: products of a deconstructed genome. Curr Opin Microbiol 16:652–658

Sun F, Xiu Z, Jiang R, Liu Y, Zhang X, Yang Y, Li X, Zhang X, Wang Y, Tan B (2019) The mitochondrial pentatricopeptide repeat protein EMP12 is involved in the splicing of three nad2 introns and seed development in maize. J Exp Bot 70:963–972

Sun F, Zhang X, Shen Y, Wang H, Liu R, Wang X, Gao D, Yang Y, Liu Y, Tan B (2018) EMPTY PERICARP8 is required for the splicing of three mitochondrial introns and seed development in maize. Plant J 95:919–932

Takemoto Y, Coughlan SJ, Okita TW, Satoh H, Ogawa M, Kumamaru T (2002) The rice mutant esp2 greatly accumulates the glutelin precursor and deletes the protein disulfide isomerase. Plant Physiol 128:1212–1222

Teng X, Zhong M, Zhu X, Wang C, Ren Y, Wang Y, Zhang H, Jiang L, Wang D, Hao Y, Wu M, Zhu J, Zhang X, Guo X, Wang Y, Wan J (2019) FLOURY ENDOSPERM16 encoding a NAD-dependent cytosolic malate dehydrogenase plays an important role in starch synthesis and seed development in rice. Plant Biotechnol J 17:1914–1927

Timmis JN, Ayliffe MA, Huang CY, Martin W (2004) Endosymbiotic gene transfer: organelle genomes forge eukaryotic chromosomes. Nat Rev Genet 5:123–135

Toda T, Fujii S, Noguchi K, Kazama T, Toriyama K (2012) Rice MPR25 encodes a pentatricopeptide repeat protein and is essential for RNA editing of nad5 transcripts in mitochondria. Plant J 72:450–460

Wang C, Aubé F, Planchard N, Quadrado M, Dargel-Graffin C, Nogué F, Mireau H (2017) The pentatricopeptide repeat protein MTSF2 stabilizes a nad1 precursor transcript and defines the 3 end of its 5-half intron. Nucleic Acids Res 45:6119–6134

Wang C, Aubé F, Quadrado M, Dargel-Graffn C, Mireau H (2018) Three new pentatricopeptide repeat proteins facilitate the splicing of mitochondrial transcripts and complex I biogenesis in Arabidopsis. J Exp Bot 69:5131–5140

Wang Y, Ren Y, Liu X, Jiang L, Chen L, Han X, Jin M, Liu S, Liu F, Lv J, Zhou K, Su N, Bao Y, Wan J (2010) OsRab5a regulates endomembrane organization and storage protein trafficking in rice endosperm cells. Plant J 64:812–824

Wittig I, Braun HP, Schägger H (2006) Blue native PAGE. Nat Protoc 1:418–428

Wu M, Ren Y, Cai M, Wang Y, Zhu S, Zhu J, Hao Y, Teng X, Zhu X, Jing R, Zhang H, Zhong M, Wang Y, Lei C, Zhang X, Guo X, Cheng Z, Lin Q, Wang J, Jiang L, Bao Y, Wang Y, Wan J (2019) Rice FLOURY ENDOSPERM10 encodes a pentatricopeptide repeat protein that is essential for the trans-splicing of mitochondrial nad1 intron 1 and ENDOSPERM development. New Phytol 223:736–750

Xiu Z, Sun F, Shen Y, Zhang X, Jiang R, Bonnard G, Zhang J, Tan B (2016) EMPTY PERICARP16 is required for mitochondrial nad2 intron 4 cis-splicing, complex I assembly and seed development in maize. Plant J 85:507–519

Yang L, Zhang J, He J, Qin Y, Hua D, Duan Y, Chen Z, Gong Z (2014) ABA-mediated ROS in mitochondria regulate root meristem activity by controlling PLETHORA expression in Arabidopsis. PLoS Genet 10:e1004791

Yang Y, Ding S, Wang Y, Wang H, Liu X, Sun F, Xu C, Liu B, Tan B (2020) PPR20 is required for the cis-splicing of mitochondrial nad2 intron 3 and seed development in maize. Plant Cell Physiol 61:370–380

You X, Zhang W, Hu J, Jing R, Cai Y, Feng Z, Kong F, Zhang J, Yan H, Chen W, Chen X, Ma J, Tang X, Wang P, Zhu S, Liu L, Jiang L, Wan J (2019) FLOURY ENDOSPERM15 encodes a glyoxalase I involved in compound granule formation and starch synthesis in rice ENDOSPERM. Plant Cell Rep 38:345–359

Zhang C, Muench DG (2015) A nucleolar PUF RNA-binding protein with specifcity for a unique RNA sequence. J Biol Chem 290:30108–30118

Zhang L, Ren Y, Lu B, Yang C, Feng Z, Liu Z, Chen J, Ma W, Wang Y, Yu X, Wang Y, Zhang W, Wang Y, Liu S, Wu F, Zhang X, Guo X, Bao Y, Jiang L, Wan J (2016) FLOURY ENDOSPERM7 encodes a regulator of starch synthesis and amyloplast development essential for peripheral ENDOSPERM development in rice. J Exp Bot 67:633–647

Zheng P, Liu Y, Liu X, Huang Y, Sun F, Wang W, Chen H, Jan M, Zhang C, Yuan Y, Tan B, Du H, Tu J (2021) OsPPR939, a nad5 splicing factor, is essential for plant growth and pollen development in rice. Theor Appl Genet https://doi.org/10.1007/s00122-020-03742-6

Zhu C, Jin G, Fang P, Zhang Y, Feng X, Tang Y, Qi W, Song R (2019) Maize pentatricopeptide repeat protein DEK41 affects cis-splicing of mitochondrial nad4 intron 3 and seed development. J Exp Bot 70:3795–3808

Zhu X, Teng X, Wang Y, Hao Y, Jing R, Wang Y, Liu Y, Zhu J, Wu M, Zhong M, Chen X, Zhang Y, Zhang W, Wang C, Wang Y, Wan J (2018) FLOURY ENDOSPERM11 encoding a plastid heat shock protein 70 is essential for amyloplast development in rice. Plant Sci 277:89–99

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by Key Laboratory of Biology, Genetics and Breeding of Japonica Rice in Mid-lower Yangtze River, Ministry of Agriculture, P. R. China, Jiangsu Collaborative Innovation Center for Modern Crop Production.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Transformation Science and Technology Program (2016ZX08001006), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2016YFD0100500), Jiangsu Science and Technology Development Program (BE2018388), and Jiangsu Province Agriculture Independent Innovation Fund Project (SCX (19)1079). This work was also supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (KYTZ201601).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LW, WZ, YW and JW conceived and designed the experiments. WZ provided the fse5 mutant material. SL, YT and XL were responsible for field work. LW, HY, YC, XT, HD, RC and XJ performed the experiments and analyzed the data. LW wrote the paper. YW revised the paper. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Figure S1.

Homozygous fse5 seeds were produced by a heterozygous plant (+/fse5). Segregation of grains with normal vitreous and floury (black, red arrows) kernels occurred among all seeds harvested from a single heterozygous plant (+/fse5) and was viewed by an X-ray viewer (PD-HA). Bar, 1 cm. Figure S2. Phenotypes of seeds and seedlings of the WT and fse5 mutant lines. A-D, 1000-grain weight (A), and length (B), width (C) and thickness (D) of mature WT and fse5 seeds. E-H, Total starch (E), amylose (F), protein (G) and lipid (H) contents of mature WT and fse5 seeds. I, Germination percentages for WT and fse5 seeds at 7 DAS in culture dishes. J, Percentages of seedlings grown from WT and fse5 seeds at 9 DAS in soil. K, Heights of 9-day-old seedlings grown from WT and fse5 seeds. The values are the means ± SDs. **, P < 0.01, Student’s t test. Figure S3. OsPORR1 KO lines generated via CRISPR/Cas9. A, KO target site in the genomic sequence of OsPORR1. B, Target sequences of the OsPORR1 allele in four independent positive lines of Nipponbare. Single-nucleotide insertions (red letters, A, T and G) occurred in KO-140, KO-155 and KO-172, and a 32-nucleotide deletion (red dotted line) was present in KO-174. The black box indicates the protospacer-adjacent motif (PAM) sequence. C, Phenotypes (upper panel) and transverse sections (lower panel) of seeds from Nipponbare and KO lines. Bars, 1 mm. Figure S4. GUS staining of various tissues from a ProOsPORR1:GUS transgenic plant. Left-to-right, young seedling, root, stem, leaf, leaf sheath, panicle and developing seed. The promoter of OsPORR1 was inserted into a pCAMBIA1381Z vector, which was then introduced into Nipponbare via Agrobacterium tumefaciens transformation. GUS staining was performed as described previously (Zhang and Muench, 2015). Bars, 2 mm. Figure S5. qRT-PCR analysis of 23 mitochondrial introns. Primers spanning adjacent exons were used to amplify fragments of mature mitochondrial transcripts (upper panel), and primers spanning adjacent exons and introns were used to amplify fragments of mitochondrial precursor mRNAs (lower panel) (Cai et al. 2017; Chen et al. 2017; Lee et al., 2017). The results of nad4 exon 1-exon 2 (spliced fragment) and its precursor fragment are indicated by a black box. ND, not detected. Three biological replicates were assessed via qRT-PCR, and OsActin1 was used as an internal control for data normalization. The values are the means ± SDs. Figure S6. Immunoblot analysis of major starch synthases. Total proteins were extracted from developing WT and fse5 seeds at 15 DAF and separated by SDS-PAGE (Takemoto et al., 2002; Wang et al., 2010). Translation elongation factor 1α (EF-1α), encoded by Os03g0177400, served as the loading control. GBSSI, Granule-bound starch synthase I. SSIIa, Starch synthase IIa. SBE, Starch branching enzyme. AGPS2b, ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase 2b. AGPL2, ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase large subunit 2. Figure S7. Multiple sequence alignment of PORR domains in OsPORR1, ZmWTF1 and AtWTF9. ZmWTF1, GRMZM2G403797; AtWTF9, At2g39120. Figure S8. Y2H assays showing that MISF68 interacts together with splicing factors of nad4 intron 1. Empty-AD and Empty-BK were used as controls. Full-length cDNAs of OsABO6 (LOC_Os01g02884), OsDEK35 (LOC_Os03g50500), OsDEK43 (LOC_Os05g11700), OsMISF68 (LOC_Os02g16650), OsEMP8 (LOC_Os08g41380) and OsPORR1 were cloned into pGADT7 or pGBKT7 vectors. The yeast transformation and screening procedures were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions (TaKaRa Bio, Kusatsu, Japan). DDO, Double dropout media (SD/−Trp-Leu). QDO, Quadruple dropout media (SD/−Trp-Leu-His-Ade). Table S1. Segregation of vitreous and floury grains from seven heterozygous plants (+/fse5). Table S2. Primers used for mapping. Table S3. Primers used for vector construction. Table S4. Primers used for splicing analysis. Table S5. Primers used for qRT-PCR analysis.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, L., Zhang, W., Liu, S. et al. Rice FLOURY SHRUNKEN ENDOSPERM 5 Encodes a Putative Plant Organelle RNA Recognition Protein that Is Required for cis-Splicing of Mitochondrial nad4 Intron 1. Rice 14, 29 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12284-021-00463-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12284-021-00463-2