Abstract

This work analyses the impact of disciplinary training on future Primary and Secondary School teachers’ decision to adopt a critical approach for teaching history. To do this, we will use a two-phase mixed methodological approach (quantitative and qualitative) to analyse the relationship between their previous training and the use of epistemological and psycho-pedagogical objectives and paradigms as outlined in a critical curriculum model. As regards data collection in the first phase, a closed questionnaire was created and validated, using a Likert-style (1–5) evaluation scale. The data was codified using the statistical package SPSS v.26.0 for subsequent analysis. The selected sample included 215 students from a Spanish university on the following courses: Degree in Primary Education (n = 145) and Master’s Degree in Secondary School Teaching specialised in history and geography (n = 70). They were all in the last stage of their initial training. In the second phase, we selected some of the students to participate in discussion groups, where they were able to go into more depth with their answers. In this way, we could better understand the link between their disciplinary training and the adoption of a determined model of history education. To do this, we separated them into three groups with different profiles: students taking the Degree in Primary Education unrelated with History (n = 8), students taking the Degree in Primary Education specialised in arts and humanities (n = 8) and students taking the Master’s Degree in Secondary School Teaching specialised in history and geography (n = 8). The data was gathered using an open coding procedure, based on several categories, which allowed us to compare the different questionnaires. The results reveal significant differences between the different groups. As such, we can conclude as to the importance of mastering epistemological disciplinary knowledge to break with certain traditions which impede innovation and make the adoption of a critical educational model more difficult.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Over the last few decades, many have highlighted the importance of analysing the perception that society and, especially, the educational community has of school, the curriculum and different subjects (Popkewitz, 1987; Goodson, 1993; Kahn and Michel, 2016). This has an impact not only on what teachers and pupils say and do, but also on the objectives attributed to academic knowledge; that is why analysis is fundamental in order to fuel fundamental changes in the educational system (McCrum, 2013; Parra and Fuertes, 2019).

To address all of this, this study will look at how a group of students in the last stage of their initial teacher training perceive history and the teaching thereof. Understanding their point of view is particularly relevant in order to identify to what extent the pedagogical disciplinary training received during their undergraduate and/or postgraduate degree(s) has encouraged them to reflect on their ideas, identify problems with the content and reconsider the objectives attributed to schooling in general and history education in particular (Adler, 2008; Pagès and Pacievitch, 2011).

Consequently, the main objective of this research is to explore the impact of disciplinary training on the representation of history by future primary and secondary school teachers and, especially, on the adoption of a critical curriculum model related to the teaching/learning of this subject. In this sense, this study will try to answer three main questions:

-

1.

How is history represented by teachers in training?

-

2.

Does disciplinary knowledge have an impact on this representation? In other words, are there significant differences between the students taking the Degree in Primary Education and those taking the Master’s Degree in Secondary School Teaching in relation with the Bachelor’s degree previously obtained?

-

3.

Has initial teacher training contributed to breaking down the more traditional perceptions of history education?

The initial hypothesis of this study is that disciplinary training conditions the perspective held by future history teachers and, as such, the adoption of determined paradigms for the teaching of history. Thus, we expect that better epistemological disciplinary training would contribute to developing a more comprehensive overview of history and the teaching thereof. That is why we hope to uncover differences between the separate groups, as well as more coherence selecting a critical curricular model by those who we presume reflect more deeply on the socio-educational use and nature of this field of knowledge.

Teaching history and curriculum models

Traditionally, history has been a key component of compulsory education curricula due to its patriotic and civic potential. It has typically been used as a tool to convey basic moral codes and socio-cultural values which have an impact on progress, unity and the cohesion of naturalised and, often, glorified nations. For this purpose, the teaching of history has been based on historical and teleological stories which were built around a few important characters and facts which tended to demonstrate nations as unified and custodial entities with supposedly immutable values which you must know, value and defend (Carretero et al., 2012; Berger and Conrad, 2015). Furthermore, this content should, especially during secondary school, provide pupils with a set culture which reinforces hierarchies and the organisation of society. This all leads to what Cuesta (2002) has called the “disciplinary code”. In other words, a socio-cultural tradition, a collective memory, based on ideas, values, assumptions and practices which legitimise the educational function attributed to a particular discipline and which regulate the order of its teaching.

Since the 1970s, the central points of this code have been questioned. From a psycho-pedagogical standpoint, the role of teachers and pupils throughout the teaching/learning process has been reassessed, which has led to a breakthrough in new methodologies and resources. From an epistemological perspective, these new standards supported a wider range of study topics, the reworking of established narratives and the demand for new objectives far removed from the old uses which were exclusively patriotic and culturalist. In this way, with regard to historicist and positivist history, we can find numerous outlooks in the news which, like history from below, history of everyday life, microhistory, cultural studies, gender, post-colonial studies, etc., focus on people, their problems and their role in society, trying to explain why they act how they do and going further than the mechanical and structuralist perspectives which diminish, when they do not negate, the individual’s ability to act. Furthermore, this all makes it possible to do and learn history in a new way, allowing pupils to develop much richer and more complex historical thinking skills with greater educational potential (Clark, 2011; Pollock, 2014; Gómez et al., 2018; Lévesque and Zanazanian, 2015; Lee, 2005; VanSledright and Reddy, 2014; Prats et al., 2019).

Despite all these changes, educational research indicates that the influence of old teachings often remains in many primary and secondary school classrooms (Tutiaux-Guillon, 2008; Cuban, 2016; Harris and Burn, 2016; Moreno-Vera and Alvén, 2020) and that the explanation lies in the social representation of these subjects. In this vein, it is vital to understand how much of an impact tradition has on maintaining the aforementioned perceptions and to evaluate the role of epistemological disciplinary training when it comes to breaking with this tradition in order to adopt new perspectives and approaches in the classroom (Martens, 2015; Miguel-Revilla et al., 2020). In this respect, as explained by many authors regarding different school subjects, it is difficult to develop consistent didactic knowledge without solid understanding of the subject matter (Hashweh, 2005; Abell et al., 2009; König, 2013). Moreover, this is closely related with the adoption of a determined curriculum model by teachers, who view the curriculum as a guide to develop practice; a guide which is not only normative, but also substantiated and reflective on the meaning and relevance of the project they are trying to develop.

With respect to the aforementioned points, in this study we will distinguish between three curriculum models (technical, practical and critical) based on relevant features such as the selection/justification of content, the role of the teacher, the selected psycho-pedagogical approaches and, of course, the desired objectives (Rozada, 1997).

The technical model fits best with the traditional vision: an exceedingly transmitter-based approach focused on the effectiveness of the teaching/learning process and the supposed objective of academic knowledge which does not question, and which generally implies the reproduction of classic and little-problematised discourse and narratives. The practical model came about as a result of the breakthrough in psycho-pedagogy, especially based on Piaget theory. This gained weight during the last third of the 20th century. Centred around the discovery teaching model, it places the focus on the pupil rather than the teacher, making the acquisition of skills and competences, as well as cognitive development, a priority. The critical model, however, puts particular emphasis on the teacher as an intellectual transformer (Giroux, 2015), who can read the curriculum critically and problematise the content. It also focuses on the teaching of history though epistemological perspectives which transcend the solely factual description, thus promoting the development of complex historical thinking, contributing to the denaturalisation of certain narratives which are deeply rooted in the educational and social environment despite having been questioned by historiography. As such, the main question for a critical curriculum theory is to know what knowledge should be taught and, above all, the objective of this selection. Curriculum theories are not founded on a purely epistemological or psycho-pedagogical basis, but on a social and cultural context with interests that are not always acknowledged. As such, in pursuance with the assumptions of critical pedagogy, it is fundamental to problematise education and to be able to consciously choose whether to reproduce or question the determined speeches or practices (Young, 1998; Tadeu, 1999). That is why this research will expose whether better education in history has an impact on the perception that future teachers have of the subject and, above all, if they can derive alternative practices clearly outlined in a critical model.

Method

Research design

The study was organised in two phases. For the first phase, a quantitative non-experimental study-type design was used. This allowed us to systematically gather information, which was particularly useful to identify the link between the variables which are the purpose of this study.

In the second phase, we chose a selection of participants from the first phase to form discussion groups they were able to go into more depth in their answers, allowing us to better understand the relationship between their disciplinary training and the adoption of a determined model of history education. To do this, each group had different training backgrounds: students from the Degree in Primary Education unrelated to history, students from the Degree in Primary Education specialised in arts and humanities and students from the Master’s Degree in Secondary School Teaching specialised in history and geography.

Context, participants and sample

The study surveyed a sample of 215 students from the University of Valencia (Spain): 145 in the 4th year of their Degree in Primary Education (43% of the total class) and 70 taking the Master’s Degree in Secondary School Teaching specialised in history and geography (87.5%). They participated during the 2019/20 academic year. At the start of the research they were all in the last stage of their initial training, just before starting their practical traineeships in educational institutions. The selection of the sample responded to a criterion of convenience. The sample was non-probabilistic (available or convenient sample), given that we deliberately chose future teachers of social sciences and history, in both primary and secondary education, with different degrees of knowledge of the subject matter.

For students taking the degree course, none of whom had a compulsory module in disciplinary training of history, 29.7% (n = 43) of participants specialised in arts and humanities (with different subject options linked with history education) while the rest (70.3%; n = 102) studied specialty pathways that had no link to history (physical education, science and mathematics, therapeutic pedagogy, hearing and speech, etc.) and, as a result, with less epistemological disciplinary knowledge training.

Of the 70 Master’s Degree students (hereafter MAES), 51.4% (n = 36) studied a degree in history, while the rest came from other degree backgrounds in which, in every case, compulsory modules on disciplinary history education were included. 40% (n = 28) had studied a degree in art history and 8.6% (n = 6) had degrees in social and human sciences (geography, humanities, archaeology and political science).

For the first phase of the study, participants were classified into four groups with respect to, from least to most, the degree of epistemological disciplinary history education (Table 1).

For the second phase, drawing from the answers to the questionnaires, 24 students were selected to participate in three discussion groups: one taking specialisations in the Degree in Primary Education with no direct link to history (DG1, n = 8), another specialised in arts and humanities (DG2, n = 8) and the third from the Master’s Degree in Secondary School Teaching (DG3, n = 8). The groups were newly formed based on the variable of disciplinary education, which is higher among master’s students (especially those with a history degree) and significantly lower among students taking the Degree in Primary Education with specialisations unrelated to arts and humanities. In all three cases, we sought to ensure a certain balance in qualifications and in the third group we also aimed to have proportional representation from the different degrees which lead to the MAES specialisations (4 in history, 3 in art history and 1 in geography).

Tools and data handling

Two tools were used to gather data. For the first phase, a structured questionnaire was designed in five sections corresponding to the different analytical categories (Table 2). The participants had to respond to the various questions through 59 items and a Likert-type scale of 5 values which range from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The first section included three items and focused on the initial training of Social Science Didactics, in particular on their self-perception of the knowledge acquired during their university studies and their education gaps. The second included 18 items. The objective was to explore the role attributed by the participants to history teachers, which involved both psycho-pedagogical and methodological aspects as well as epistemological and attitudinal factors. The third section also included 18 items. It focused on the strategies and resources of the history class. Finally, the questionnaire ended with two sections dedicated to two key aspects to define the adoption of a curricular model: the content selected and the objectives and uses attributed to the teaching of history (12 items in each section).

The questionnaire was validated by two experts in the field of Social Science Didactics and one in Sociology. In addition, the Alfa de Cronbach coefficient was used to estimate the internal consistency of the tool and the degree of reliability given a blend of items based on Likert-type scale questions. It is believed that this coefficient, used in other studies of a similar nature (Gestsdóttir et al., 2018; Gómez et al., 2018), demonstrates internal consistency when the values are higher than 0.7 or 0.8. With the questionnaire we used, we obtained highly satisfactory results with an Alfa coefficient equalling 0.898.

The information processing and analysis was performed using the statistical package SPSS v.26.0. For this study, not all the questionnaire items were used. Thus, in order to analyse the data and interpret the results, we completed basic descriptive statistics (averages and variations) using certain concrete items based on three categories (teacher’s role, content and objectives) on the one hand and on the other proof of equality in medians and contrast with these same items grouped in line with three previously described curricular approaches: technical, practical and critical. Given that the Levene variation homogeneity test resulted in a value under 0.05, we turned to the Welch and Brown-Forsythe equality in medians tests, a robust alternative to the F statistics of ANOVA when it is not possible to assume that the sample variations are equal. To identify which average differed from which other, we used a multiple post hoc comparison. In order to avoid assuming equal variations, we checked using the Games–Howell method to establish the contrast. Finally, to estimate within which limits there were true differences between the group averages, a group-based classification was carried out based on the degree of similarity between the averages. To do this, given that the classification is not available for all methods, we used Tukey’s HSD test despite the fact it cannot take into the account the equality of variations.

Once the first phase was completed, we used the discussion group technique for the second phase. This strategy is based on group debate around a concrete topic which provides information as to perceptions, ideas and opinions which are often qualified or strengthened as a result of the interaction and which, for the case we are working on, is particularly useful for deeper understanding of the participants’ responses (Onwuegbuzie et al., 2009).

As regards the design and preparation process, 24 participants from the previous phase were selected and separated into three groups, as previously explained. When organising and planning the groups, we ensured that the number of participants would not be below 8, given that it was convenient to ensure diversity without an overly crowded environment which would complicate or impede free expression of opinions. The length of sessions exceeded 90 min in order to achieve, within the limits of research of this type, better data collection.

The moderating team was made up of two authors of this article whose task it was, mainly, to guide the conversation, reorient it at determined times and facilitate that which is now known as stimulating materials: in other words, texts, images or photographs which are designed to spark ideas, feelings or reactions amongst the participants.

The sessions were video recorded, with authorisation from the participants, and later analysed in line with an open coding procedure based on a series of categories which allowed for comparison with the questionnaires. For the analysis, not only were individual ideas considered, but also the degree of consensus or dissent within the group or the possible censorship or marginalisation of certain ideas, which is very relevant to research of these characteristics (Onwuegbuzie et al., 2009; Davidson, 2010).

The discussion groups were organised into six sections (Table 3). The first, of an introductory nature, aimed to explore the perception participants had of school and the changes that were needed in their opinion. The second and third sections, specifically focused on the topic of history, sought to approach the curriculum and the convenience of some content compared to others. This allowed us to evaluate their ability to query the curriculum as well as the degree of responsibility they would have as future teachers, both in relation with their ability to interpret/question the content prescribed by the normative framework as well as to extend this (from a richer epistemological perspective) or connect it with socially relevant problems. The fourth and fifth sections related to their teacher training and their perception of what makes a good history teacher. This helped us see if they put more focus on psycho-pedagogical, epistemological disciplinary or attitudinal aspects and evaluate to what extent their greater or lesser knowledge of history predisposed them to certain factors or others. Finally, the sixth section was created as an applied exercise with the aim of checking whether, beyond the declared level, they detected the continued existence of objectives and approaches typical of a traditional model, within a concrete, apparently innovative, teaching/learning exercise and whether they were able to suggest alternatives. One of the activities involved experiencing a recreation of a medieval tournament with their students, based on the glory of great characters from the past, with a profoundly historical perspective and marked character identity. The objective was to see if they were able to question the narrative of this performance, to detect deficiencies and limitations and contribute to recreating an alternative tale about facts which are deeply entrenched (and, as such, naturalised) in their collective memoryFootnote 1.

Secondly, we suggested another exercise based on the use of a WhatsApp group to summarise the medieval history of the Iberian Peninsula; an experiment implemented in classrooms by a social sciences teacher in the 1st year of secondary school who exclusively focused on chronology, important political events and the names of different peoples and civilizations (Romans, Visigoths, Muslims, etc.) Footnote 2.

Results and discussion

Questionnaire

In order to fulfil the purpose of this research, certain items related to a critical assessment of the curriculum were selected alongside others which will serve as a counterpoint and help to nuance the results obtained. Namely, the selection is based on items related with the role of the teacher, the content and objectives of history class.

With regard to the role of teachers, the results of the questionnaire (Table 4) show that there is agreement on the importance of understanding the ideas already held by pupils, both from a cognitive as well as a socio-cultural perspective. However, this is greater in the case of Degree students (QG1 and QG2), who have more psycho-pedagogical training than Master students (QG3 and QG4). Conversely, for items 13, 14 and 17 (based on purely axiological and even political aspects) those with greater epistemological disciplinary education prefer a more critical approach which does not involve shying away from more controversial topics for the purpose of supposedly neutral knowledge. Here we notice differences between Master and Degree students, as well as, among the latter, between those with specialisations unrelated to history (QG1) and those specialised in arts and humanities (QG2).

Consistent with what we just outlined, within the selected items regarding more “innovative” content (Table 5), we identified no significant differences in the responses given by the different groups of participants. As such, they all very much agree on including topics related to recent epistemological angles and with great educational potential (items 8–10), even if the feeling is stronger among members of QG2, future primary school teachers. This includes skills-related content involving the development of historical thinking (item 11). The differences are more accentuated in the items (1 and 3) which refer to a descriptive and factual history, with a historicist style, and generally linked with the grand master theories, including national narratives. In the case of this more traditional content, although there is less support in all groups, students with extra disciplinary training (QG4) are more clearly opposed to it. On this point, we should highlight that one of the most notable differences within the group of Master students relates particularly to the national(ist) dimension associated with the importance given to the “main historic events in the history of Spain” (item 3). For this item, QG3 students are much less critical than those with a degree in history (QG4), with viewpoints more like those of the students taking the Degree in Primary Education (QG1 and QG2). Among the latter, perhaps the most remarkable point is the contradiction between the supposed neutrality that, according to most of the future primary school teachers, the teacher should embody (to be precise, in order to avoid controversial topics in the classroom) and the preference, in this case, for socially relevant and explicitly controversial topics. This leads us to think that, for many participants, these topics could be addressed in a non-divisive way, ignoring the social and political nature and, as such, its great potential for civic education.

Despite all this, the items selected to discuss objectives (Table 6) allowed us to best identify the impact of more comprehensive education on history and the teaching thereof. Once again, there are no big differences in the items which refer to the acquisition of cognitive skills or competences or those linked with the development of abstract historical thinking (items 5, 7, 8, 10). There was not much difference either on the item about questioning reality and inherited agreements (item 11), although students with greater disciplinary training (QG4) and history didactics (QG2) were more inclined to this objective. However, there were significant differences in the items which relate to traditional objectives (items 1 and 4) such as the “acquisition of general knowledge” (understanding historic culture as an academic and stagnant aspect of the past) or the “understanding of our origins as a people” (a solely identity-related objective). These answers were provided more frequently by the students taking the Degree in Primary Education than those on the Master course.

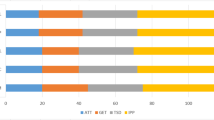

If we focus on analysing the items grouped into the three outlined categories (Role of teacher = RT; Content = Con; Objectives = Obj) to evaluate the degree of conformity with the different curricular models (Traditional = T; Practical = P; Critical = C), we see, first of all, that the Welch and Brown–Forsythe equality of variances tests show that the p-value is <0.05 in all cases. This means that we can reject the hypothesis of equality of medians and conclude that the average values of the compared groups are not equal for any of the categories (Table 7).

To find out which averages differ from each other, we used the Games–Howell test, which allowed us to check all the possible combinations two at a time between the levels of the variable factor (education), the differences between the averages of each two groups, the typical margin for error in these differences and the associated degree of importance of each one (Table 8). The groups whose averages differed significantly (<0.05) are highlighted with an asterisk.

The confidence intervals reflected in Table 8 allow us to estimate between which limits lies the true difference between the group averages. As such, we note that, the more disciplinary education received (QG4), the more there is coherence in the responses (rejecting the traditional approaches and supporting the critical approaches). On the same line we noted Tukey’s HSD test, which classifies groups according to the similarities between their averages (Tables 9 and 10). In this way, we can see that are not great differences between the groups when it comes to selecting individual content or objectives from a practical or critical curricular model (Con P, Con C, Obj P and Obj C), but there are differences regarding support for traditional content or objectives (significantly less depending on the degree of disciplinary training (Con T and Obj T).

All of this does not allow us to confirm, on the one hand, that support for critical tenets is greater in all the groups, as is reflected in the homogenous subsets following the completion of the Tukey test. On the other hand, it demonstrates that, with more epistemological disciplinary training, there is greater rejection of the more traditional content and uses (to the extent that QG3 and, especially, QG4, make up separate subsets due to their scarce support for this approach). Consequently, we can deduce that the responses given by the Master students, especially QG4, are much more coherent and consistent than those of the Degree students, given that support for the critical model goes hand in hand with greater opposition to more traditional tenets. Conversely, students taking the Degree in Primary Education tend to positively evaluate all these items. This demonstrates more incoherence, in particular amongst those who studying the arts and humanities specialisation, despite their declared preference for certain innovative educational premises that are closer to a critical approach.

Discussion groups

The discussion groups were crucial to being able to more comprehensively match up and analyse the perceptions, gathered using a quantitative tool such as a questionnaire, of history teaching by teachers in training. The analytical categories used to present the results refer to the selection of content, methodology and resources, the psycho-pedagogical perspective of the teacher and the objectives of the process of learning and teaching history.

The various discussion groups started with the projection of a photograph of a “traditional” classroom in which pupils are seated in rows, individually working through the activities in a book. Using this as a starting point, the group members reflected on and debated the practices and uses of school in general. Most MAES students (DG3) cited the need for changes in teacher training in order to be able to tackle everyday challenges and classroom management: “I could stand up for myself in a class about the RestorationFootnote 3, but not in case of harassment” (B3). They also suggested changes in methodology “to move away from the rote technical model” (L3) and content because it is not appropriate for critical-type objectives: “Often, the content that is presented in the course books doesn’t try to shape critical citizens” (E3).

Students of the Degree in Primary Education specialised in arts and humanities (DG2) agreed with this assertion, although they underscored methodological, rather than epistemological, changes. This is proven with this thought: “what’s most important is not the content, but rather the way in which we approach it” (E2). The focus on methodological aspects was even stronger in the discussion group of students taking the Degree in Primary Education with different specialisations (DG1). In this case, new technologies were highlighted as a driver of educational change: “The photograph exemplifies shortfalls in education: individualism, a plan, an exercise book, a book and a lack of technology” (N1).

The curriculum was often mentioned as restricting potential educational changes. In fact, many of the Degree students view the curriculum as an obstacle to approaching a subject from a more critical perspective because “it is quite limiting, and we have to follow it” (F1). “The legal framework doesn’t make it easy to address certain socially relevant topics which can be sensitive in nature.” (I2). Even so, there were more detailed opinions regarding the degree of hindrance caused by the curriculum, especially in DG2: “The curriculum doesn’t impede, but it is a considerable obstacle” (X2). Among students with greater disciplinary training in history, the idea that the curriculum could be interpreted was most popular: “The curriculum doesn’t have to be a restriction if we can make critical use of it.” (P3). In this case, the teacher wasn’t viewed as simply an emissary but rather as an agent of change. External examinations are highlighted as a restriction “especially for the Baccalaureate” (E3).

If we focus on the selection of content for history classes, the answers students gave in the questionnaire to the question “Which topics do you believe are the most relevant in history class?” revealed a prevalence for attitudinal-type knowledge, related to human rights, the struggle for equality, the everyday life of common people and controversial political and social subjects (ideologies, religious, national, gender, class identities, etc.). Hardly any differences were noted between the different sample groups. The discussion groups helped us specify and coordinate these answers which could generate a wrong impression regarding the adoption of a critical curricular approach by history teachers in training.

In the discussion groups, students taking the Degree in Primary Education rejected the traditional approach which encompasses traditional factual content, processes and major periods or historical elements. However, this dismissal did not go hand in hand with an epistemological alternative, but rather was often based solely on methodological change: “We need to remove dates, battles and famous figures; perhaps it’s difficult to change the content or to know which changes to implement and these are very abstract questions, […] but I know that we need to change the methodology. What’s clear is that teaching nowadays is failing methodologically given that my brothers don’t remember any of the facts” (K1). This same student alluded to the necessary “connection between the content and personal experience (interviewing grandparents or people who lived through the civil war.)”, but instead of underlining the critical potential of the history of everyday life, the student emphasised—from a constructive point of view—the relationship with the pupil’s surroundings and methodological change: “We need to go beyond lectures”. In the same vein, another student mentioned methodology and resources as key to changing the teaching of history, disregarding the content: “During my traineeship, I observed the topic of industrialisation being taught in 6th grade. They used new technologies and gamification, which the pupils won’t forget. […] As such, the curriculum should include methodological changes which are closer to the pupil’s experience.” (F1).

Conversely, there was more support for epistemological change among the group of MAES students (DG3), where they proposed the introduction of socio-cultural history linked with the study of socially relevant problems. The students in this group backed up this epistemological approach with a wealth of examples which showed their mastery of the content: “workers’ rights” (L3), “idea of nation” (B3), “working classes” (C3), “gender” (E3), “gender roles in the Roman family” (P3), etc.

The MAES students, and more clearly those with a Degree in History, explained why changing the content is necessary to move toward a more socio-cultural and contentious approach. Amongst other things, they mentioned bringing it home to pupils to drive interest and motivation, because it made history a living and useful thing for the present or just something that’s fairer and more democratic: “This content has to go beyond a mere factual transfer of knowledge and should serve to defend democratic values” (P3). To sum up, only the sample with more disciplinary education was able to propose alternative content emphasising the epistemological, rather than the methodological, aspects.

In addition to the selection of content, methodology and resources, the teacher’s role was a key category of analysis for this piece of research. In the questionnaire, we asked about their role in the classroom, and the discussion groups were able to elaborate on what makes a good history teacher. For students taking the Degree in Primary Education, a good teacher would be “a person who promotes meaningful learning” (E2), “who brings history to life and explains it in an entertaining way” (A2), “who is sympathetic and emotionally intelligent” (X2) and of course “who knows the content” (K1). Equally, a teacher who takes “what pupils know” (N1) into account was rated highly. The focus, as we can see, was not on shaping critical citizens, but rather on achieving meaningful learning, demonstrating the relevance of methodological and cognitive perspectives among future primary school teachers.

Although most participants focused on methodological aspects, some, especially in DG2, referred to teaching models encompassing a critical approach: “which encourage debate and social conflict, situations linked with what goes on in the outside world, to go beyond the merely academic and connect with reality” (I2). They also suggested a series of topics with a critical theme: “A good teacher would change your perception of vulnerable communities, women, LGTBI, etc.” (H2), although they often forgot to refer to socio-economic problems.

The idea of a “neutral” teacher was particularly popular amongst students taking the Degree in Primary Education, especially in DG1. In other words, “their opinion shouldn’t be noticeable” (F1). The reasons given for this included “to avoid problems with families and give the children freedom to think what they want” (N1). Students agreed with this premise, although they agreed that socially relevant topics should not be avoided “in order to help shape critical citizens” (E2). Once again, they referred to the methodology used to address these subjects, opting for debates, “role swaps” (F1) or empathy.

If, on the other hand, we look at DG3, students mainly discussed the necessary didactic training and commitment, describing the role of the teacher as clearly rooted in a critical approach. They said that a good teacher “doesn’t avoid controversial topics” (C3). To a lesser extent, they described the need to promote historical thinking: “We need to establish past-present analogies” (P3) or “put ourselves in the shoes of Victoria Kent to understand why she fought in the way she did” (E3).

None of them rejected tackling socially relevant problems and most students clearly expressed that it was appropriate to study them. In contrast to students taking the Degree in Primary Education, students in this case were for the most part critical of the positivist idea of neutrality: “A history teacher cannot be even-handed. We need to break with the idea of objectivity and abiding by the book (which is not objective). […] A good teacher must be able to read the materials critically” (P3); “a good teacher must be engaged and not tolerate certain xenophobic or macho behaviours” (E3). Despite the fact that they shared this criticism of the neutrality of history teachers, some students who had completed a degree in geography or art history nuanced this commitment: “You need to be an engaged teacher, but subtly: more through your selection of sources rather than openly giving your opinion” (I3). In the same way, they differentiated students who experience external conditioning (type of centre or religious orientation) as a hindrance to the teacher’s social engagement.

This discussion ties in with the last category for analysis, the objectives of a history class. In the questionnaires, we saw that most of the participants taking the Degree in Primary Education supported traditional objectives such as “acquiring general knowledge”, “understanding the main events and historic figures which help us understand our origins as a people” or “teaching the mistakes of the past so as not to make them again”, although to a lesser extent than objectives which are more related to practical and critical models. In the discussion groups DG1 and DG2, the debate about objectives was a feature of each section. In fact, at times, the students reclaimed it by highlighting that “rather than content, we need to think about the objectives, there’s not enough debate about why we want to teach history” (H2). The students in DG1 agreed that memorising dates and facts was not relevant for a history class, but they did not clearly highlight the critical objectives. Crucially, the students taking the Degree in Primary Education championed objectives of the procedural type (arguing, debating, analysing sources, etc.), referring to the skills of historical thinking (comparing past and present, historical empathy, etc.). In some cases, erudite perceptions or the idea of history as magistra vitae came up, with teachers whose objective is a better society and “not repeating the mistakes of the past”: “the Civil War would be an interesting subject to tackle on this topic, addressing how it happened, as a lack of respect and understanding” (Na1). In this case, a socially relevant topic was used to learn lessons of a moral nature rather than problematising it as a burning issue.

We only find examples of explicitly critical objectives in DG3, which is coherent with what we observed regarding other questions examined by the discussion groups. Addressing socially relevant themes or problematising the past was seen by most group participants studying the Master’s degree as the main objectives of history class, thus adopting the premises of critical didactics.

As previously noted, the discussion groups finished with an applied exercise aimed at showcasing the importance that these teachers in training—both for Primary and Secondary Education—attributed to the epistemological or methodological aspects when thinking about an alternative history class. The first resource used to corroborate the participants’ critical perspective referred to the use of a WhatsApp group to summarise the history of the Middle Ages on the Iberian Peninsula. In this real experiment, as already explained, a clearly superficial overview of historical knowledge was given, reduced to a series of dates and names. The answers given by DG1 were mainly positive and uncritical of the “clarity of the resource” (F1), its “originality and dynamism” (N1) given that it is a TIC resource. Those with more disciplinary education, on the other hand, expressed a more critical perspective. As such, in DG3, they all highlighted that, despite the entertaining approach which is draws the pupil in, it could only serve as a complement (to grab their attention or to put the topic into context or revise an already studied topic), given that it is “reductionist” (B3), “superficial” (I3, P3), “simplified” (O3). In any case, only one participant specifically mentioned the content to raise an issue: “it reduces a whole people or civilization to a WhatsApp providing a stereotyped perspective” (B3).

The second resource, also about the Middle Ages (in this case specifically about the Valencia region) led to further debate. It involved a trip to a performance—The King’s Tournament—dedicated to the mythologised figure King James I and to the 9 October, the day on which the Christian conquest of Muslim Valencia culminated in 1238 and the current Day of the Region, carrying great weight for school celebrations (Parra and Segarra, 2012). The synopsis of the performance shown to the students clearly revealed the essentialist identity-based conception linked to the national Catholic narrative of the History of Valencia and Spain, as well as the focus on famous figures and military events. The objective of this question was to see whether, beyond the declared level, the students detected the persistence of an approach reflecting traditional or technical models and were able to suggest alternatives. With this question we also aimed to check if the responses given in the different sections of the questionnaire really displayed a critical conception of History or if, on the contrary, they were mere statements without clear reasoning.

The responses given in this exercise corroborate the hypothesis suggested at the beginning of this study. The participants in DG1 believed that attending this theatrical performance would be a “good idea”. In this vein, they emphasised the supposedly innovative nature of the proposed methodology, given that it is a theatrical resource. Some thought it was positive and accentuated the identity-related nature (in an essentialist sense) of the suggestion, because it “lets you identify with your nation”. Others voiced objections, although they demonstrated little ability to critically read the document provided: “I can’t find anything I don’t like in the leaflet, but I would prefer to see it to check if it is patriotic, xenophobic, etc.” (N1). On the other hand, in a clear example of the differences between the two groups of students taking the Degree in Primary Education, the DG2 students were not in favour of attending the performance, defending their opinion by emphasising the problem the content and objectives presented. They agreed, in any case, that if they attended the performance it had to be done with an approach that questions the narrative promoted thereby: “We cannot ignore the 9th October, we need to transfer it to the classroom and fuel debate. Going to the performance could help with that” (I2). In the same way, they condemned the uncritical use of this resource by teachers who went to see it with pupils merely as a “transmitter, with no changes or didactic explanations” (H2).

Similarly to DG2, but with a more complex and reasoned discussion, all the students in DG3, with the most disciplinary history education, detected the essentialist identity-related vision of the theatrical performance and rejected it as a resource: “a history teacher has to break away from these national myths and dismantle the iconic figure of James I” (E3). Those who said they could go to see it suggested, in line with what was proposed by some DG2 students, it as an opportunity to deconstruct narratives and traditional myths: “given how it would entertain pupils, it could be interesting to go and deconstruct it: give more visibility to Muslims, etc. The performance could be a starting point to problematise these events” (B3). This point of view relates with the socio-cultural perspective for history classes that they defended in earlier questions in the discussion group.

As observed in the analysis of the two resources submitted for discussion, the DG1 students underlined methodological innovation rather than the content of the resources presented. Only those with more disciplinary education, specifically in the didactics of history, criticised the content of the resources. This was noted among the students taking the Degree in Primary Education specialised in arts and humanities (DG2) and, more clearly, among the MAES students (DG3). It would have been complicated to evaluate students’ responses if we only had the questionnaire to go by, given that, in their results, the students were in favour of using alternative materials that went beyond the traditional textbook without explaining how they were used or the objective thereof. As such, at the end of the day both examples demonstrate the wealth of information obtained through qualitative methodologies such as the discussion groups.

Conclusions

As we have observed throughout this study, the use of mixed methods (quantitative and qualitative) is an excellent alternative in order to tackle educational research topics. On the one hand, it allows us to more comprehensively understand the phenomenon that is the subject of the study and, on the other, to explore the subject in more depth both with general and specific questions to hear the participant’s perspectives.

As regards the results obtained, we can conclude that, at a declared level, the future primary and secondary school teachers have already adopted part of the suggested practical and critical curricular models. However, we cannot infer a complete break with the disciplinary code of history nor with the technical curricular model by all participants.

As proven by both the questionnaires and the discussion groups we analysed, disciplinary epistemological education has an impact on the perceptions of history and its socio-educational uses, which confirms the initially suggested hypothesis. Significant differences are identified, on the one hand, between the students taking the Degree in Primary Education with specialisations unrelated with history and those with a specialisation in arts and humanities and, on the other hand, between the MAES students who studied a degree in history and other participants. The questionnaires show that, although support for the suggestions reflecting practical and critical models is higher in all groups, the higher the disciplinary education, the greater the rejection of more traditional uses and content. As such, we can infer that the responses given by the MAES students, especially those with a Degree in History, are much more coherent than those given by the students taking the Degree in Primary Education, who reveal inconsistencies and superficial positions by positively evaluating items which indicate the opposite point of view. The discussion groups allowed us to further examine these points, because they also revealed contradictions among the future teachers and demonstrated that greater disciplinary education helped develop much richer and more complex didactic knowledge of the content and pursue socio-educational objectives deeply rooted in critical didactics. In this sense, participants of DG1 and, to a lesser extent, of DG2 viewed educational innovation as mainly focused on methodological aspects or the introduction of new resources. For the DG3 students, it was mainly about deep reflection on the reasons behind the content and desired objectives.

Finally, we can confirm that, in the case of the future primary school teachers, initial teacher training has given them the tools to suggest alternatives from a methodological or even psycho-pedagogical perspective. However, without a solid disciplinary basis, certain consensuses are easily undermined, turning toward the development of materials, their content, their public use or their educational practices. Therefore, despite the apparent mass support of all groups for practical and critical perspectives, a certain continuance of traditional content, narratives and practices remains amongst the future primary school teachers, or simply changing resources and strategies as a link with innovation. It is clear that students taking the Degree in Primary Education with a specialisation in arts and humanities are more inclined than the others to challenge traditional content and uses. However, when compared with MAES students, they demonstrate notable gaps which we attribute to worrying shortfalls in the curriculum of disciplinary history education, both in this specialisation as well as in the whole Degree in Primary Education at the University of Valencia. In contrast, we notice that the MAES students, who have further epistemological training and mastery of the content, have the tools at their fingertips to question hegemonic discourse, problematise the past and suggest more solid alternatives with the aim of civic education.

In conclusion, the differences between the various groups of future teachers are a relevant aspect in teacher training. It clearly points to the convenience of creating specific formative curricula which, beyond methodology and cognitive aspects, to a greater extent lead to the necessary questioning of the curriculum, the content and why it is being taught.

Data availability

The datasets generated during the current study are not publicly available because the identities of some participants are visible, undermining privacy protection. Nevertheless, the datasets generated are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Notes

You can watch the promotional video of the performance here: http://culthisme.com/el-torneo-del-rey/.

You can view the resource and experiment here https://verne.elpais.com/verne/2017/10/14/articulo/1507980132_294582.html.

Period in contemporary Spanish history between 1874 and 1923.

References

Abell SK, Park MA, Hanuscin DL et al. (2009) Preparing the next generation of science teacher educators: a model for developing PCK for teaching science teachers. J Sci Teacher Educ 20(1):77–93. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10972-008-9115-6

Adler SA (2008) The education of social studies teachers. In: Levstik LS, Tyson CA (eds) Handbook of research in social studies education. Routledge, New York, pp. 329–350

Berger S, Conrad C (2015) The past as history. National identity and historical consciousness in modern Europe. Palgrave McMillan, London

Carretero M, Asensio M, Rodríguez M (ed) (2012) History education and the construction of national identities. IAP, Charlotte

Clark P (ed.) (2011) New possibilities for the past. Shaping history education in Canada. UBC Press, Vancouver-Toronto

Cuban L (2016) Teaching history then and now: a story of stability and change in schools. Harvard Education Press, Cambridge

Cuesta R (2002) El código disciplinar de la historia escolar en España: Algunas ideas para la explicación de la sociogénesis de una materia de enseñanza. Encount Educ 3:27–41

Davidson C (2010) Transcription matters: transcribing talk and interaction to facilitate conversation analysis of the taken-for-granted in young children’s interactions. J Early Child Res 8:115–131

Gestsdóttir SM, Van Boxtel C, Van Drie J (2018) Teaching historical thinking and reasoning: construction of an observation instrument. Br Educ Res J 44(6):960–981. https://doi.org/10.1002/berj.3471

Giroux HA (2015) Schooling and the struggle for public life: democracy’s promise and education’s challenge. Taylor and Francis

Gómez CJ, Rodríguez RA, Mirete AB (2018) Percepción de la enseñanza de la historia y concepciones epistemológicas. Una investigación con futuros maestros. Rev Complut Educ 29(1):237–250. https://doi.org/10.5209/RCED.52233

Goodson I (1993) School subjects and curriculum change. Falmer Press, London

Harris R, Burn K (2016) English history teachers’ views on what substantive content young people should be taught. J Curric Stud 48(4):518–546. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220272.2015.1122091

Hashweh MZ (2005) Teacher pedagogical constructions: a reconfiguration of pedagogical content knowledge. Teachers Teach 11(3):273–292. https://doi.org/10.1080/13450600500105502

Kahn P, Michel Y (eds) (2016) Formation, transformations des savoirs scolaires: histoires croisées des disciplines, XIXe-XXe siècles. Presses Université de Caen, Caen

König J (2013) First comes the theory, then the practice? On the acquisition of general pedagogical knowledge during initial teacher education Int J Sci Math Educ 11(4):9991028. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10763-013-9420-1

Lee P (2005) Putting principles intro practice: understanding history. In: Donovan M, Bransford J (eds) How students learn: History in the classroom. National Academies Press, Washington, pp. 31–77

Lévesque S, Zanazanian P (2015) History is a verb: “We learn it best when we are doing it!”: French and English Canadian prospective teachers and history. Rev Estudios Soc 52:32–51

Martens M (2015) Students’ tacit epistemology in dealing with conflicting historical narratives. In: Chapman A, Wilschut A (eds) Joined-up history: new directions in history education research. Information Age Publishing, Charlotte

McCrum E (2013) History teachers’ thinking about the nature of their subject. Teach Teacher Educ 35:73–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2013.05.004

Miguel-Revilla D, Carril-Merino T, Sánchez-Agustí M (2020) An examination of epistemic beliefs about history in initial teacher training: a comparative analysis between primary and secondary education prospective teachers. J Exp Educ. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220973.2020.1718059

Moreno-Vera JR, Alvén F (2020) Concepts for historical and geographical thinking in Sweden’s and Spain’s Primary Education curricula. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 7(107). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-00601-z

Onwuegbuzie AJ, Dickinson WB, Leech NL et al. (2009) A qualitative framework for collecting and analyzing data in Focus Group research. Int J Qual Methods 8(3):1–21

Pagès J, Pacievitch C (2011) Instrumentos para la evaluación de las representaciones sobre la profesión de profesor de ciencias sociales, de geografía e historia del alumnado del máster de secundaria. In: Miralles P, Molina S, Santisteban A (eds) La evaluación en el proceso de enseñanza y aprendizaje de las Ciencias Sociales. AUPDCS, Murcia, Murcia, pp. 379–389

Parra D, Fuertes C (eds) (2019) Reinterpretar la tradición, transformar las prácticas: Ciencias Sociales para una educación crítica. Tirant lo Blanch, Valencia

Parra D, Segarra JR (2012) Celebraciones escolares, ¿Fiestas cívicas? El tratamiento escolar del 9 d’octubre y del día de la Constitución en las aulas valencianas de educación primaria. Didáct Cienc Exp Soc 26:19–34

Pollock SA (2014) The Poverty asn possibility of historical thinking: an overbiew of recent research into history teacher education. In: Sandwell R, Heyking AV (eds) Becoming a history teacher. University of Toronto Press, Toronto, pp. 60–74

Popkewitz T (1987) The formation of school subjects: the struggle for creating an American Institution. Falmer Press, London

Prats J, Fuentes C, Sabariego M (2019) La investigación evaluativa de materiales didácticos para la educación política y ciudadana a través de contenidos históricos. Rev Electrón Interuniv Form Profr 22(2):1–15. https://doi.org/10.6018/reifop.22.2.370051

Rozada JM (1997) Formarse como profesor. Ciencias Sociales. Primaria y Secundaria Obligatoria. Akal, Madrid

Tadeu T (1999) Documentos de identidade: uma introdução às teorias do currículo. Autêntica, Belo Horizonte

Tutiaux-Guillon N (2008) Interpréter la stabilité d’une discipline scolaire: l’histoire-géographie dans le secondaire français. In: Audigier F, Tutiaux-Guillon N (eds.) Compétences et contenus. Les curriculums en question, De Boeck, Brussels, pp. 117–146

VanSledright BA, Reddy K (2014) Changing epistemic beliefs? An exploratory study of cognition among prospective history teacher. Tempo Argum 6(11):28–68

Young MFD (1998) The curriculum of the future. From the «New sociology of education» to a critical theory of learning. Falmer Press, London

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the research project “The social representations of educational content in the development of teaching competencies” [PGC2018-094491-B-C32], funded by the Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities of Spain and co-funded by the ERDF.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Parra-Monserrat, D., Fuertes-Muñoz, C., Asensi-Silvestre, E. et al. The impact of content knowledge on the adoption of a critical curriculum model by history teachers-in-training. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 8, 64 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-021-00738-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-021-00738-5