Abstract

Labour Market Information forms a central place in career practice and how individuals enact their careers. This paper makes use of Alvesson and Sandberg’s (Constructing research questions: doing interesting research. Sage, Thousand Oaks, 2013) methodology of focussing research on theoretical assumptions to construct a critical literature review on the relationship between Labour Market Information and career guidance. This paper presents six theoretical conceptions from the career literature: Contact, Rationalism, Nomad, Adaptability, Constructivist and Social Justice. We will argue for the need to move towards more constructivist understandings of Labour Market Information as well understandings linked to more critical understandings of the labour market.

Resumé

Information sur le marché du travail et justice sociale : Une perspective critique La « Labour Market Information (LMI) » – L'information sur le marché du travail – occupe une place centrale dans la pratique professionnelle et dans la manière dont les individus mènent leur carrière. Cet article utilise la méthodologie d'Alvesson et Sandberg (2013) qui consiste à concentrer la recherche sur les postulats théoriques pour construire une revue de littérature critique sur la relation entre la LMI et l'orientation professionnelle. Ce document présente six conceptions théoriques présents dans la littérature sur les carrières : Contact, Rationalisme, Nomade, Adaptabilité, Constructiviste et Justice sociale. Nous allons plaider pour la nécessité d'évoluer vers des compréhensions plus constructivistes de l'information sur le marché du travail ainsi que vers des interprétations liées à des compréhensions plus critiques du marché du travail.

Zusammenfassung

Arbeitsmarktinformationen und soziale Gerechtigkeit: Eine kritische Betrachtung Arbeitsmarktinformationen nehmen einen zentralen Platz ein in der beruflichen Praxis und bei der Laufbahngestaltung. Dieser Beitrag nutzt die Methodik von Alvesson und Sandberg (2013), um die Forschung über theoretische Annahmen über die Beziehung zwischen den Arbeitsmarktinformationen und der Laufbahnberatung einer kritischen Literaturübersicht zu unterziehen. In diesem Beitrag werden sechs theoretische Konzeptionen aus der Laufbahnliteratur vorgestellt: Kontakt, Rationalismus, Nomade, Adaptabilität, Konstruktivismus und soziale Gerechtigkeit. Wir werden für die Notwendigkeit argumentieren, sich in Richtung eines konstruktivistischen Verständnisses von Arbeitsmarktinformationen zu bewegen, sowie für ein Verständnis, das mit einem kritischeren Verständnis des Arbeitsmarktes verbunden ist.

Resumen

Información sobre el Mercado Laboral y Justicia Social: Una Revisión Crítica La Información sobre el Mercado Laboral (IML) ocupa un lugar esencial en la práctica profesional y en el modo en que las personas desarrollan sus carreras. Este artículo utiliza la metodología de Alvesson y Sandberg (2013) sobre focalización de la investigación en supuestos teóricos para construir una revisión crítica de la literatura que vincula la IML con la orientación para la carrera. Este artículo expone seis concepciones teóricas de la literatura sobre la carrera; Contacto, Racionalismo, Nómada, Adaptabilidad, Constructivismo y Justicia Social. Aportaremos argumentos sobre la necesidad de avanzar hacia una mayor comprensión constructivista de la Información sobre el Mercado Laboral, así como hacia una comprensión vinculada a una visión más crítica del mercado laboral.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

This article presents a critical literature review of the relationship between Labour Market Information (LMI) and career guidance. We will particularly explore the underpinning theories which are used in the field to discuss LMI and how these relate to social justice. For the purposes of this article, we will define LMI in the same way that Esbrogeo and Melo-Silva (2012) do as ‘data from the occupational world’ which helps people with their career decisions. This creates a broad definition for LMI which incorporates everything from economic forecasts, sector trends, job-specific information, educational training, recruitment processes and beyond. As the wider literature shows, Labour Market Information (LMI) has a crucial relationship to career guidance. Parsons (1909) foundational description of career guidance saw a need for individuals to bring together a right knowledge of self with a right knowledge of opportunity. Parsons conception of a ‘right knowledge of opportunity’ can be seen as a precursor to the concept of LMI as described by Esbrogeo and Melo-Silva (2012). Parsons conceptions has been developed through a range of understandings of career guidance most notably in the DOTS (Decision learning, Opportunity awareness, Transition learning, Self-awareness) model (Watts, 1977) which similarly draws attention to the place of ‘opportunity awareness’ in career guidance. This has been developed into a long standing tradition where career guidance recognises the importance of engaging clients with information (Bimrose & Barnes, 2006). In light of its centrality to the field of career guidance this article will conduct a critical examination of LMI. The purpose of this will be to explore the theoretical understandings of LMI currently in circulation in the field. This article will therefore be significant for the field of career guidance by challenging existing understandings of LMI and then proposing a new theory of LMI linked to current understandings of the importance of social justice for the field of career guidance.

Though other literature reviews of LMI have been conducted (Esbrogeo & Melo-Silva, 2012; Gore et al., 2013) these have focussed on the nature of LMI and have not explored LMI from a theoretically explicit perspective. This is not uncommon across literature in this field where the relationship of LMI to theory tends to be under-developed, under-problematised or even entirely ignored. Work by Alexander et al. (2019) has done more to relate thinking about LMI to theory, and especially to understandings of social justice. Alexander et al. focus on how LMI can be used to promote social injustice. We will argue that current theories of LMI obscure injustices in the world of work. In this way we hope to build on the important link that Alexander et al. make but also show the need of different ways of theorising the relationship between LMI and social justice. Particularly we will explore how LMI is constructed ideologically and can be seen as serving rather than exposes oppressive agendas.

The focus of this review will be to explicitly explore the theories and metaphors at play in the literature in this domain. This paper will make use of Alvesson’s (Alvesson & Kärreman, 2011; Alvesson & Sandberg, 2013) writings on the place of theory in literature reviews to underpin our methodology in this review. Alvesson particularly focuses on how literature is underpinned by theories and metaphors and as a consequence how exploring these is of particular use for generating more interesting research.

Methodology

Hart (2018) draws attention to the range of different approaches to literature reviews as paralleling the different approaches to research design. This review falls into a scholastic review as described by Hart (2018), a review focussed on using rigorous conceptual analysis to explore a domain of literature as opposed to focussing on practice and implications of the research. In this study, we hope to make use of Hart’s description of Barnett-Page and Thomas’ literature review work (2009) which is described as providing a review of literature as well as a review for research; this means our aim is both to set out an understanding of what the literature has said and also to look at how this can be moved forward into a new agenda for research in this domain.

Methodologically a key feature of this article is the extensive use of the work of Sandberg and Alvesson’s (2011) as the basis for our literature review. Sandberg and Alvesson note that much academic writing in the Social Sciences relies on reviewing literature in a domain in order to spot the holes in existing research and so aim to contribute to the field by filling in these holes or expanding the field beyond its current state. Sandberg and Alvesson argue that a significant problem with this approach is that it requires you to take on the epistemological and theoretical positions of a body of work in order to contribute to it. This leads to less interesting research which does little to develop new ways of thinking. Sandberg and Alvesson (2011) put forward problematisation as an alternative to this. The important mark of this critical perspective (as opposed to other approaches which they also discuss) is to avoid using pre-packaged critiques from other existing perspectives (mainly by using grand theories such as feminism or Marxism) but instead being prepared to re-formulate received wisdom in an effort to break the logic of received traditions. Alvesson and Sandberg (2013) recommend a five-stage process to look at how to develop novel and interesting theoretical insights in an area through problematisation. This process is as follows;

-

1.

Identify a domain of literature

-

2.

Identify and articulate the assumptions of the literature

-

3.

Evaluate these assumptions

-

4.

Develop alternative assumption(s)

-

5.

Consider the relationship to the audience

We are going to structure the rest of the article by working through the five points which Alvesson and Sandberg discuss and using them as headings for our article.

Firstly though, we need to contextualise this methodology for the specific topic we are exploring in this article. Our aim is to explore how the career guidance literature has discussed the manner in which LMI can be seen to support individuals and communities learning about career. In light of Alvesson and Sandberg’s (2013) work this aim can be split into the following research objectives;

-

1.

Explore how the relationship between the labour market and career guidance has been discussed in careers theory and practice

-

2.

Target the metaphors and assumptions that underpin these understandings

-

3.

Develop alternative theories and assumptions that can be used to open up new understandings.

Identify a domain of literature

Returning to the methodology from Alvesson and Sandberg (2013) we set out above we have already identified the domain of study as LMI and its relationship to career. Alvesson and Sandberg (2013) go on to argue that when it comes to delimiting a domain of literature it is more important to establish key or typical texts in order to conduct in-depth readings of these to challenge their assumptions. It is less important to compare your ideas against the majority of texts in a field as you would typically do in a ‘gap-spotting’ study. This said, being able to select typical texts is only possible once an overall survey has been carried out in order to establish the main contours of the domain.

To this end, an initial literature search was carried out. This was not limited by date. A series of search terms were developed from a combination of the author’s existing knowledge of the field and an initial skim of some common career guidance publications. The following search terms were used in the initial literature search; Labour/Labour Market Information, Labour/Labour Market Intelligence, LMI, Careers Information, Opportunity Awareness, Occupational Information, Career Learning and Career Research.

To access this literature we searched across three main types of source. Firstly we looked at a number of well-known journals which covered career guidance (including International Journal of Vocational Guidance, British Journal of Guidance and Counselling, Journal of Career Assessment, The Career Development Quarterly, Journal of Vocational Behavior, Australian Journal of Career Development). Secondly we conducted searches on a series of academic research databases (Web of Science, Scopus and EBSCO). Finally we also conducted searches on Google Scholar in order to identify grey literature. Inclusion criteria was developed looking at articles which (1) explored the place of information and opportunity awareness (2) in relation to career (3) how this impacted on either career guidance practice or career development and that (4) had this as a significant concern of the article. No explicit exclusion criteria was used beyond this.

The initial literature search yielded 186 articles for our review. Articles were selected through an initial reading of the title and the abstract of the article. Articles were then saved into a collaborative document on a popular cloud-based platform.

Identify and articulate the assumptions of the literature

The next task was to identify the underlying metaphors and theories at play in these articles. Slife et al. (1995) discuss the need to root out the un-criticised assumptions in a domain and to do this through a dialectic between the literature domain, the pre-existing theoretical stances in the literature and alternative theoretical stances. The first stage of this is to draw out the assumptions that currently exist in the literature. Alvesson and Sandberg (2013) describe five types of assumptions that can exist in a domain of literature; (1) in-house assumptions (2) root metaphor assumptions (3) ideological assumptions (4) paradigmatic assumptions (5) field assumptions. This typology can be used as different lenses to explore literature and problematise it. We will return to these later in the article.

In order to make a decision on which form of assumptions to focus on a second, more detailed, reading of the articles was completed. This second reading focussed on drawing out the assumptions and theories at play in the literature. This was done firstly by coding different relationships that were described between LMI and career enactment and then sorting these codes into themes where a theme was seen as a broader description of the position taken by the authors. These themes were then analysed for their underlying assumptions. Both the set of the codes and the assumptions were developed in an emergent manner rather than using pre-set categories. Up to three codes were added to each article and up to two overall themes. This second reading also led to the list of articles reducing to 155 as some articles were found not to be sufficiently focussed on the main aspects of the study.

This particular approach of making use of codes and themes is widely used in qualitative analysis and, particularly for our interest, in content analysis (Krippendorff, 2018). This is different from Alvesson and Sandberg (2013) who prefer a tight reading of key texts to develop themes. As we will show later we will use this as part of our methods but conducting this sort of overview includes more material in this study as well as creating a more structured way to select key texts.

The table below shows the list of codes and their frequencies as well as the themes which the concepts were sorted under (Table 1).

Once the frequency of the themes was analysed as above the following frequency of themes was established.

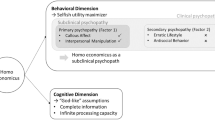

As suggested by Alvesson and Sandberg (2013) a small number of key texts were selected inside each of the themes which were then re-read in depth. For all of the domains five texts were read except for the constructivist domain where only three were identified in the domain. These texts were chosen because of their focus on the theme and their prevalence in the wider career literature. Once the emergent themes were developed wider careers literature was used to clarify and develop them further. The relationship to existing concepts in the careers literature is described below. The six categories which were developed are as follows:

Contact (32 articles)

We found a cluster of articles which focussed on the provision of LMI to individuals. The theme of contact was developed to describe a view that merely coming into contact with LMI would produce beneficial results for individuals without articulating any detail about how this occurred. As a consequence, the focus in this theme was on how governments and other bodies can ensure the provision of LMI and not on how individuals could make use of LMI. This top-down approach appears to be generally technocratic in nature and lacks attachment to developed theories of career enactment and decision making. A key example in this theme comes from Saniter and Siedler (2014) who study the effects of levels of LMI on labour market outcomes but in their study, they proxy levels of occupational knowledge with visiting German ‘Job Information Centres’. An assumption is made that increasing provision increases knowledge and that learning about this sort of information happens automatically. Hirschi (2011) argues that providing careers information is correlated with increased career readiness report scores. This takes a similar ‘black box’ approach where providing information is seen as having a positive effect but without exploring how these two ideas are linked in the individual. This provision focussed account was also seen in Hutchinson (2018) who uses the benchmarks developed by the Gatsby Foundation (Holman, 2014) to analyse career provision in five English independent schools. One of her key findings is that provision of information in these schools was one of the shared markers of quality (something the Gatsby Foundation’s benchmarks particularly look for). Interestingly Hutchinson (2019, p. 62) recognises the limits of just exploring provision in this way stating ‘research on the individual learning impacts would be fruitful to determine the nature of that learning among pupils’. This draws attention to the critical limitation of this conception which just looks at LMI from the point of view of provision and does not explore what happens in the experience of the individual receiving it.

Rationalism (120 articles)

As can be seen by the table above (Table 2), the most common theme described was rationalism. Rationalism has a long tradition in the career literature going back to the work of Parsons (1909) and Holland (1973) who underpinned the theories of career choice with a matching model where individuals and opportunities could be aligned and measured in a scientific (rationalistic) manner. This matching process required a ‘proper’ understanding of the opportunities available to the individual which in turn created a focus on the quality of information supporting rational decisions. Gati (1986), Gati et al. (1996) and Gati and Asher (2005) has written a wide range of literature on career decision making from a predominantly psychological perspective. We particularly focussed on Gati et al.’s (1996) article A taxonomy of difficulties in career decision making. In this Gati et al. develop a taxonomy of 10 career decision-making difficulties. Of interest to us is that Gati et al. describe lack of information and unreliable information as being detrimental to career decision making. This draws a link between decision making and LMI as supporting individuals making a verifiable match. This is similar to Germeijs and Verschueren (2007) who argue that there is a necessity for individuals to explore a breadth and a depth of LMI to underpin effective decision making, an analysis also backed up by Skinner (2019); Eriksson et al. (2018) and Crişan et al. (2015). These articles focus on a need for LMI of sufficient quality to support quality decisions. This focus on quality information needed to support decision-making runs throughout these articles and is often focussed on the accuracy of information but issues of bias (Christie, 2016; Hughes, 2010) and currency (Andrews, 2013; Bennett, 2012; Balaram & Crowley, 2012) provide extra detail to this account. This theme picks up on ideas of quality information originally developed by Mollerup (1995) and dating back to Parsons’ (1909) conception of a ‘right’ understanding of opportunity. The underpinning rationalism in these articles can be seen in the belief that quality LMI supports quality decisions, this fits into a wider paradigm that distinguishes between career decisions on the basis of external, objective criteria. In this paradigm quality LMI is seen as part of the factors that can support an objective, quality decision.

Constructivism (3 articles)

Constructivism has increasingly grown to prominence in the domain of career theory from Super’s (1953) workaround self-concepts onwards. Fundamentally constructivism links to post-modern understandings of knowledge to move away from rationalism’s focus on verifiable and scientifically testable knowledge to understandings of career which are plural, subjective and personally situated or as McMahon and Patton (2016) have postulated reality is constructed ‘from the inside out’. This does not lead to a radical individualism but what McMahon and Patton view as a ‘contextualist’ view of reality where meaning is constructed by the individual who is in contact and dialogue with the world around them. Meaning is not absolute and objective, it is constructed by the individual. But this process of ‘meaning-making’ is not done by an isolated individual but through an individual who is contextual, an ‘open-system’ (McMahon and Patton 2016) in ongoing dialogue with their environment. As the low article count implies writing around constructivism and career has focussed on matters related to self-awareness and decision making and has not engaged in detail with LMI as a concept. When looking at particular articles that use this theme Grubb (2002) draws attention to what he sees as the inadequacies of careers information as a policy driver and instead argues for the need to adopt constructivist practice that focuses on identity construction and individuals directly exploring and understanding opportunities for themselves. This provides a different approach to opportunity awareness than providing information and is interestingly different from Savickas (1997) and McMahon and Patton (1995) who have tried to reconcile constructivism as a theory underpinned by a subjectivist epistemology with more traditional and objective understandings of LMI and occupational awareness. The contextualist foundations of constructivism opens a potential direction to explore LMI from a different epistemic standpoint. This remains a somewhat unexplored tension in the literature around career construction where there has not been much exploration of how its theoretical stance can be reconciled with the standards of accuracy and objectivity that tend to be linked with LMI.

Nomad (17 articles)

The metaphor of the nomad is one developed out of writing about the relationship between digital technology and education. It refers to the ability of technology to provide access and connections for learners who can now gain autonomy over their education so their trajectories are less pre-defined and linear in nature (Cormier, 2008; Emejulu & Mcgregor, 2019). Though not without critique (Selwyn, 2016) this metaphor picks up on how digital technology has transformed the way individuals can access and make use of information. From a career enactment perspective, Hooley (2012) has described how digital technology changes the nature of career partly by creating a greater focus on individuals to use digital tools to develop their own careers in a more personalised manner. Central to this is the need for individuals to develop ‘digital career literacies’ to enable them to access and assess information online for themselves. This focus on personalisation is picked up by Kettunen et al.’s (2013) term ‘co-careering’ which articulates the change in power dynamics in online environments and the increasing agency which individuals have to explore career information for themselves. Though these theories do still align with broadly rationalist ideas (for example they are concerned with the accuracy of information) the difference here is the predominance of digital technology and the role of individuals in using it to create a personal environment where they access information for themselves.

Adaptability (7 articles)

Career adaptability is a growing domain of careers theory concerned with uncertainty and especially how the rapidly changing labour market impacts on career enactment. Building on work from Bright and Pryor (2011), Krumboltz and Levin (2010) and Savickas (1997) these articles look at the need to build the ability to respond and adapt to an uncertain world more than the ability to make one-off rational decisions. The key articles we looked at saw contact with LMI as affecting the sort of attributes that underpin adaptability as a concept. Hiebert et al. (2012) looked to move away from analysing the form of LMI to discussing its impacts. Their study revealed LMI based interventions increasing optimism and confidence. Similarly, Artess and Hanson (2017) and Ghanam et al. (2012) found LMI to encourage motivation and inspiration. These items optimism, confidence, motivation and inspiration all chime with similar ideas developed by Bright and Pryor (2011), Krumboltz and Levin (2010) and Savickas (1997). Rather than seeing LMI as impacting on the ability of individuals to make decisions they instead see LMI as having an impact on individuals ability and willingness to take action in an uncertain world.

Social Justice (7 articles)

As Furbish (2015) among others has argued, Social justice as a lens for career enactment and career guidance has a long tradition whether it be looking at Parsons (1909) original work as a social reformer (Plant & Kjaergård, 2016) through Watts’ (1996) exploration of career guidance’s links to politics and its radical potential to Irving and Malik (2004) and Hooley et al. (2017, 2018) more recent work. Social justice is less a single theory as it is a multi-dimensional perspective on career guidance. These various positions attempt to explore how career guidance can contribute to conceptions of what is seen as morally right or good for society (Hooley et al., 2018), it is a movement away from just seeing career guidance as underpinned by economic necessity or individual benefit to contributing towards wider social and moral imperatives. Various studies did look at how social justice could be brought about through careers practice focussed on LMI. They tended to look at how either social equity or social equality (Sultana, 2014) could underpin career guidance. Flederman (2011), in a case study from South Africa, talked about how disadvantaged populations tended to have less access to LMI and where they did it was of lower quality. By doing so she argues for the need of disadvantaged populations to access LMI in order to improve their career outcomes. This is similar to Doyle’s (2011) findings of lower socio-economic status university students in Australia and Rai’s (2013) case study of recent immigrants in Canada who also highlight the disadvantage some groups face due to not being able to access or make use of LMI. Flederman (2011) also highlights another issue from a social justice perspective of LMI not being representative of disadvantaged groups. This moves away from equality as the main lens for social justice and instead looks at representation and social norms as lenses through which to analyse the relationship between social justice and LMI. As Sultana (2014) and Irving and Malik (2004) have argued, equity and equality are just two perspectives on social justice.

Shared assumptions

In this section we are going to draw attention to two shared assumptions that sit across the six themes we have discussed above. Firstly, almost all of the themes we discussed view LMI as developing occupational knowledge which is fixed and definitive (except Grubb 2002). In this view, knowledge is arranged in a canonical manner and individuals build on previous knowledge and progress towards having adequate understanding. This creates a description of learning which brings together two related ideas; that occupational knowledge is fixed and uncontested and that it is to an individual's benefit to build on what they currently know and acquire more of this fixed knowledge. We can see this in the place of accuracy as a concept across a number of different themes. In terms of rationalism Gati et al.’s (1996) discussion around lack of information and unreliable information affecting decision-making leans on the idea that individuals need enough information of a good enough quality which heavily relates to this idea of fixed knowledge. The theme of the nomad does the same with Hooley (2012) discussing the skills needed to critique online information to understand its authenticity, again giving the impression that information would fall into one of two camps, accurate or inaccurate. Similarly the theme of social justice often sees disadvantaged groups coming into contact with inaccurate information which amplifies their disadvantage, something which both Doyle (2011) and Rai (2013) drew attention to. Importantly even adaptability as a theme mainly still upholds accuracy as a category, the challenge is how long this knowledge lasts for or how useful it is. This ignores the contestability of the world of work. The labour market could be viewed from different perspectives using a range of theoretical resources and it could be understood differently depending on the individual's position in society. This does not mean that there is no such thing as the labour market or that it is entirely removed from facts. Instead, the tension comes around which facts to prioritise, this is the level at which this contestation occurs.

Secondly, the prevailing view from the existing literature was that the labour market itself was unproblematic and neutral for the individual and that the output of careers work should be better integration in the labour market. Alexander et al. (2019) did explore inequalities in the labour market. They argue that LMI can be used to challenge inequalities in the workplace by better informing clients of the world around them and so adapt to it and challenge it. Our review postulates that this view is in minority with most of the literature viewing the main use of LMI as integrating individuals into the workforce rather than helping them critique it. Also, we will go on to explore how Alexander, McCabe and De Backer’s work does not explore how LMI and its construction can contribute to injustice.

The problem the individual faces are generally seen as how they will get a job which they find personally beneficial. For example, Gati et al.’s (1996) frame put the emphasis on individual decision making, this frame moves the locus of responsibility towards the individual as needing to make good decisions and solve their own problems. Similarly, under the adaptability theme Hiebert et al. (2012) and Ghanam et al. (2012) focus on the output of career interventions being individuals being motivated to take action in the world. Hooley (2012) mentions being critical as a digital career literacy that individuals should develop, this is linked to understanding the accuracy of information and not critically exploring issues related to injustice and oppression inside the labour markets. These articles ignore or side-lines the idea that there might be dangers for individuals in the labour market but instead holds the view that any engagement with the labour market is good engagement. As we are seeing the themes we discussed did not significantly engage with the idea that the labour market might itself be a site of oppression and difficulty because of how it relates to conceptions of justice. Even the articles that existed inside the theme of social justice tended to see the end of social justice as the integration of individuals into the labour market rather than being wary of the labour market as an entity as a whole or wanting to investigate it as a site of potential oppression. This unproblematic neutrality runs through the themes.

These two themes of (1) canonical knowledge, and (2) a neutral labour market, are the two main assumptions we are going to look at for the rest of the study. Alvesson and Sandberg (2013) have set a way of classifying assumptions. Though our first assumption is paradigmatic in nature due to its interaction with epistemology taken together these assumptions are best seen as representing ideological assumptions about the nature of career and career development. Alvesson and Sandberg (2013) see ideological assumptions as ones which are understood by reference to political and ideological categories.

Evaluate these assumptions

Alvesson and Sandberg (2013) look at a number of ways to evaluate an assumption. The first of these is to ask if the assumption is true, does it map onto the world? Alvesson and Sandberg (2013) warn against making this the only criteria but it is still a helpful place to start. We will return to consider canonical knowledge later but for now, let us consider our second assumption of the labour market being neutral, i.e. it is not problematic in nature for individuals. This can easily be countered by pointing to research that shows that work itself is the site of violence (Baron & Neuman, 1996), bullying (Samnani & Singh, 2016) and harassment (Feldblum & Lipnic, 2016). These studies highlight not just that these problems exist in society including in workplaces but that they are in various ways developed, shaped and propagated by workplaces. Critical perspectives focussing on ethnicity, gender and class offer obvious roads into critiquing the view that the labour market is neutral. This connects with the developing body of work focussed on ‘decent work’. Initially developed through an agenda set out by the ILO (1999) and then furthered by authors such as Ghai (2003), Blustein et al. (2016) and Duffy et al. (2017). Decent work aims to describe the basic dignities that should be available to all individuals through work. Critical perspectives are also advanced by Frayne (2015) has argued that far from being neutral and unproblematic work itself is often unjust and damaging for individuals as well as being maintained by ideological structures which are far from naturally occurring. It seems that in light of the above evidence that it is not just the case that work can be viewed from a more critical perspective but that it is pretty close to untrue to state or imply that workplaces and the labour market, in general, is neutral and unproblematic. As we noted above, this distinction is generated by reference to political and ideological categories (Alvesson & Sandberg, 2013).

As well as considering the truthfulness of the assumptions we have uncovered Alvesson and Sandberg (2013) also discuss the potential to evaluate assumptions by asking what the fruitfulness or ‘provocative capacity’ or developing alternative assumptions might be. Both of the assumptions we outlined, that knowledge of the labour market is canonical and that the labour itself is neutral, take limiting views around what LMI is. By their nature, they focus on a reading of reality which lacks creative possibilities or much chance of integration into other theoretical traditions. The idea that knowledge is canonical and linear means that the primary question asked about information is to do with its accuracy and perceived rational benefit. This assumption only allows certain types of knowledge into its cannon as useful or beneficial and has the potential to limit what we look to as career information. Similarly, as we described above, the idea that workplaces are neutral cuts out a wide range of theoretical traditions and attempts to focus investigation away from theories that ask difficult questions about labour markets and workplaces. We would argue that these assumptions are by themselves constraining and do not open up understanding or create the groundwork for other theoretical work to build upon it. These assumptions restrict the way that the labour market can be understood. Though this is partially the case with any position we would argue that the assumptions which are made use of here are particularly limiting.

Develop alternative assumption(s)

Central to Alvesson and Sanbderg’s (2013) view of developing alternative assumptions is to avoid being ‘programmatic’ by which they mean using a pre-set critique, such as feminism, Marxism, post-colonial theory etc., which will just develop a predetermined response. In contrast, Alvesson and Sandberg discuss using theories as resources but maintaining a dialectic between these theories and the domain to create new and interesting ways of developing theories and research questions. This can involve using counter-induction, borrowing metaphors from different fields or making reversal of existing assumptions. The important touchpoints for this approach is that they create the possibility for a plurality of views rather than having pre-set outcomes.

For this paper, we are going to look at how the idea of a reversal could be made use of to develop some new insights into our field. The assumptions that we identified before can be summarised as the prevailing assumptions in the literature is that learning about the ‘labour market involves building canonical, objective, knowledge about a subject which is neutral, unproblematic and safe for individuals.’ A way to reverse this would be to re-describe this as ‘learning about the labour market involves constructing personally situated knowledge about a subject which is politically and ideologically contested.’

Constructing personally situated knowledge

This assumption is that individuals experience the phenomenon in the world differently and have different architecture in place which they make use of to understand the world around them. This chimes with McMahon and Patton (2016) statement that reality is constructed ‘from the inside out’ and is contextual rather than universal in nature. This is similar to Collins’ (1981, p. 3) statement about relativism and empirical knowledge where they state that ‘the natural world has a small or non-existent role in the construction of scientific knowledge’. While the assumptions above give the impression that LMI is a representation of ‘the natural world’ Collins (1981) instead argues that the role of the natural world in developing knowledge should be reduced. To give an example in our domain of LMI believing that knowledge can build on itself in a linear manner assumes (i) that what everyone needs to know about the labour market is broadly the same and (ii) there are broadly speaking universal conclusions to what we discussed under the previous point. To flesh this out while a question like ‘what skills does someone need to do this job?’ is normally presented as a list of transferable skills, qualifications and experiences from a constructivist perspective we would want to view the personal, local and social nature of how this question is answered. Firstly, because competence is not, from this point of view, measurable but instead socially constructed through norms and traditions, secondly, because individuals will adopt different strategies depending on their understanding of competence and their capacities and social positions and thirdly, because competence will be understood by different people who interact with the role in different ways (managers, customers, co-workers, professional bodies, unions etc.)

This analysis moves LMI away from something that represents reality and instead understands it as socially constructed and viewed differently by individuals and groups in different contexts and traditions.

About a subject which is politically and ideologically contested

This extends the previous point by arguing that one of the main ways that LMI is constructed is in order to support political and ideological ends. This is to say that LMI is constructed out of a context that enforces a set of norms and ideologies around work. While traditionally the careers sector has held up unbiased information as a mark of quality (Mollerup, 1995) this position argues that all information is biased in that it is created in a political and ideological context for political and ideological purposes. This view argues that truth claims are made in relation to political and ideological causes. Though some items which contribute towards information may still be factually verifiable (e.g. wages) their truthfulness does not stop them from becoming an artefact with a political purpose and carrying out a ‘system-supporting’ function (Herman & Chomsky, 1988). Herman and Chomsky in ‘Manufacturing Consent’ refer to how the media organisations who produce news for public consumption produce a form of propaganda and control through the narratives they produce and exclude from public discourse. Importantly for our purposes, this is not seen by Herman and Chomsky as being necessitated by media organisations being untruthful, but instead producing propaganda where the news is used to create, develop and sustain public narratives as a form of social control. This can be used by us as a way to problematise the production of LMI as politically and ideologically sustained which moves past traditional understandings of quality. The interaction between LMI and politics which we are trying to develop here can be seen from a ‘bottom-up’ perspective as well as the ‘top-down’ manner we have discussed above. This builds on Hooley’s (2015) framework for emancipatory guidance and especially some of the key areas of learning which Hooley highlights such as ‘exploring ourselves and the world where we live, learn and work’, ‘developing strategies that allow us collectively to make the most of our current situations’ and ‘considering how the current situation and structures should be changed.’ From this perspective, LMI can be constructed by individual groups in light of the difficulties and injustices which they face and used by them to create horizons for action to change the world. It, therefore, becomes an important project to explore this understanding of developing LMI as a way to forward a conception of social justice. Particularly a conception which is linked to Sultana’s (2014) description of a social justice tradition linked to difference and hospitality. Hooley (2015) uses Sultana’s work to define the perspective of social justice as pluralism and difference, which moves justice away from fairness and instead looks at the project of enabling individuals to express their humanity and their perspectives on reality and ultimately gain the agency to build a world which recognises this humanity.

Consider the relationship to the audience

Alvesson and Sandberg (2013) encourage researchers to consider the importance of their research to the various audiences who might interact with it. We will do this by considering researchers and practitioners in turn. We will do this through looking at three contributions of interest to researchers and one contribution for practitioners.

This paper has contributed to the field’s understanding of LMI in relationship to careers enactment in a number of ways. Firstly, by mapping the existing themes inside the careers literature we were able to develop an overview of research in this arena. Six themes were developed from this analysis; adaptability, constructivist, contact, nomad, rationalism and social justice. Through this, we uncovered the dominance of rationalistic understanding of LMI. Our analysis shows that this position LMI was linked to rationalism and matching theory. Though we have not primarily taken a ‘gap-spotting’ approach in this paper we still feel that the careers literature could evidently be improved by adopting other theoretical positions (for example constructivist or adaptability based positions) to explore LMI. We hope that by drawing attention to these theoretical positions future authors in this area can be clearer about their own positions and will be encouraged to explore different theoretical relationships to LMI. In many ways, this relationship remains under-theorised in the careers literature and is in need of investigation.

The central contribution of this paper has been to explore the underpinning assumptions which have been made in the career literature to date. The assumptions that we identified in the literature was that ‘learning about the labour market involves building canonical, objective, knowledge about a subject which is neutral, unproblematic and safe for individuals.’ We have developed an alternative assumption which is that ‘learning about the labour market involves constructing personally situated knowledge about a subject which is politically and ideologically contested.’ The advantages of this assumption are that it opens up the field to be built on in a wider range of theoretical directions and that it asks more challenging and provocative questions about the relationship between LMI and career which can be developed in more interesting directions. We hope that thinking about constructivist epistemologies and social justice, especially when linked to pluralism, as a critical lens on LMI can move the discussion in the careers literature to more fertile ground.

Finally, the ideas set out in this paper create challenges and opportunities for practitioners. Specifically, they open up important questions for practitioners who want to explore more socially just practice, namely that the relationship with LMI needs to be explored from a social justice perspective. The paper also creates a series of theoretical observations which practitioners could use to move practice forward, for example how non-rationalistic understandings of LMI could underpin careers practice.

References

Alexander, R., McCabe, G. & De Baker, M. (2019). Careers and labour market information: an international review of the evidence. Education Development Trust.

Alvesson, M., & Kärreman, D. (2011). Qualitative research and theory development mystery as method. Sage.

Alvesson, M., & Sandberg, J. (2013). Constructing research questions: Doing interesting research. Sage.

Andrews, D. (2013). The future of careers work in schools in England: what are the options. The CDI.

Artess, J., & Hanson, J. (2017). Evaluation of Careers Yorkshire and the Humber Inspiration activity and Good practice guide. International Centre for Guidance Studies, University of Derby.

Balaram, B., & Crowley, L. (2012). Raising aspirations and smoothing transitions. The Work Foundation. Available at: https://www.educationandemployers.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Raising-Aspirations-and-Smoothing-Transitions.pdf

Barnett-Page, E., & Thomas, J. (2009). Methods for the synthesis of qualitative research: A critical review. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 9(1), 59. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-9-59

Baron, R. A., & Neuman, J. H. (1996). Workplace violence and workplace aggression: Evidence on their relative frequency and potential causes. Aggressive Behavior, 22(3), 161–173.

Bennett, R. (2012). Careers education, information, advice and guidance for young people in Hastings & St Leonards: CEIAG in an uncertain world. An Oak Project. Available at: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.467.2762&rep=rep1&type=pdf

Bimrose, J., & Barnes, S. A. (2006). Is career guidance effective? Evidence from a longitudinal study in England. Australian Journal of Career Development, 15(2), 19–25. https://doi.org/10.1177/103841620601500205

Blustein, D. L., Olle, C., Connors-Kellgren, A., & Diamonti, A. J. (2016). Decent work: A psychological perspective. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 407. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00407

Bright, J. E., & Pryor, R. G. (2011). The chaos theory of careers. Journal of Employment Counseling, 48(4), 163–166. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-1920.2011.tb01104.x

Christie, F. (2016). Careers guidance and social mobility in UK higher education: practitioner perspectives. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 44(1), 72–85. https://doi.org/10.1080/03069885.2015.1017551

Collins, H. M. (1981). Stages in the empirical program of relativism—Introduction. Social Studies of Science, 11(1), 3–10. https://doi.org/10.1177/030631278101100101

Cormier, D. (2008). Rhizomatic education: Community as curriculum. Innovate: Journal of Online Education, 4(5). Available at: http://nsuworks.nova.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1045&context=innovate

Crişan, C., Pavelea, A., & Ghimbuluţ, O. (2015). A need assessment on students’ career guidance. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 180, 1022–1029. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.02.196

Duffy, R. D., Allan, B. A., England, J. W., Blustein, D. L., Autin, K. L., Douglass, R. P., & Santos, E. J. (2017). The development and initial validation of the Decent Work Scale. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 64(2), 206. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000191

Emejulu, A., & Mcgregor, C. (2019). Towards a radical digital citizenship in digital education. Critical Studies in Education, 60(1), 131–147. https://doi.org/10.1080/17508487.2016.1234494

Eriksson, H., Högdin, S., & Isaksson, A. (2018). Education and career choices: How the school can support young people to develop knowledge and decision-making skills. Universal Journal of Educational Research, 6(9), 1900–1908.

Esbrogeo, M. C., & Melo-Silva, L. L. (2012). Career information and career guidance: A literature revision. Psicologia USP, 23(1), 133–155. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0103-65642012000100007

Feldblum, C. R., & Lipnic, V. A. (2016). Select task force on the study of harassment in the workplace. US Equal Employment Opportunity Commission.

Flederman, P. (2011). A career advice helpline: A case study from South Africa. International Journal for Educational and Vocational Guidance, 11(2), 111–123. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10775-011-9202-7

Frayne, D. (2015). The refusal of work: The theory and practice of resistance to work. Zed Books Ltd.

Furbish, D. (2015) Social justice: A seminal and enduring career counseling ideal. In Maree, K. & Di Fabio, A. (Eds.), Exploring New Horizons in Career Counseling (pp. 281–296). Sense Publishers.

Gati, I. (1986). Making career decisions: A sequential elimination approach. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 33(4), 408. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.33.4.408

Gati, I., & Asher, I. (2005). The PIC model for career decision making: Prescreening, in-depth exploration, and choice. In Contemporary models in vocational psychology (pp. 15–62). Routledge.

Gati, I., Krausz, M., & Osipow, S. H. (1996). A taxonomy of difficulties in career decision making. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 43(4), 510. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.43.4.510

Germeijs, V., & Verschueren, K. (2007). High school students’ career decision-making process: Consequences for choice implementation in higher education. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 70(2), 223–241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2006.10.004

Ghai, D. (2003). Decent work: Concept and indicators. International Labour Review, 142, 113–144.

Ghanam, D., Reavley, M., Phillip, A., Smith, D., & O’Hara, S. (2012). The impact of labour market information delivery modes on worker self-efficacy in employment related outcomes in South-western Ontario. Canadian Journal of Career Development, 12(2), 20–34.

Gore, P. A., Leuwekre, W. C., & Kelly, A. R. (2013). The structure, sources, and uses of occupational information. In Brown, S. & Lent, R. (Eds.), Career development and counselling: Putting theory and research to work (pp. 507–535). John Wiley and Sons.

Hart, C. (2018). Doing a literature review: Releasing the research imagination. Sage.

Herman, E., & Chomsky, N. (1988). Manufacturing Consent. Pantheon Books.

Hiebert, B., Bezanson, L., O'Reilly, E., Hopkins, S., Magnusson, K., & McCaffrey, A. (2012). Assessing the impact of labour market information: Final report on results of phase two (field tests). Canadian Career Development Foundation (CCDF).

Hirschi, A. (2011). Career-choice readiness in adolescence: Developmental trajectories and individual differences. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 79(2), 340–348. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2011.05.005

Holland, J. L. (1973). Making vocational choices: A theory of careers. Prentice-Hall.

Holman, J. (2014). Good career guidance. The Gatsby Charitable Foundation.

Hooley, T. (2012). How the internet changed career: framing the relationship between career development and online technologies. Journal of the National Institute for Career Education and Counselling, 29(1), 3–12.

Hooley, T. (2015). Emancipate yourselves from mental slavery: self-actualisation, social justice and the politics of career guidance. University of Derby.

Hooley, T., Sultana, R., & Thomsen, R. (Eds.). (2017). Career guidance for social justice: Contesting neoliberalism. Routledge.

Hooley, T., Sultana, R.G. & Thomsen, R. (2018). The neoliberal challenge to career guidance: Mobilising research, policy and practice around social justice. In Hooley, T., Sultana, R.G. & Thomsen, R. (eds.), Career guidance for social justice: Contesting neoliberalism. Routledge.

Hughes, D. (2010). Social mobility of young people and adults in England: The contribution and impact of high quality careers services. Careers England.

International Labor Organization [ILO], (1999). Report of the director-general: decent work. In Proceedings of the International Labour Conference, 87 Session. International Labor Organization.

Irving, B. A., & Malik, B. (Eds.). (2004). Critical reflections on career education and guidance: Promoting social justice within a global economy. Routledge.

Kettunen, J., Vuorinen, R., & Sampson, J. P., Jr. (2013). Career practitioners’ conceptions of social media in career services. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 41(3), 302–317. https://doi.org/10.1080/03069885.2013.781572

Krippendorff, K. (2018). Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology. Sage Publications.

Krumboltz, J. D. & Levin, A. (2010). Luck is no accident: Making the most of happenstance in your life and career. Impact Publishers.

McMahon, M., & Patton, W. (1995). Development of a systems theory of career development: A brief overview. Australian Journal of Career Development, 4(2), 15–20. https://doi.org/10.1177/103841629500400207

Mollerup, C. (1995). What is good information? University of Oregon.

Parsons, F. (1909). Choosing a vocation. Houghton Mifflin.

Plant, P., & Kjaergård, R. (2016). From mutualism to individual competitiveness: Implications and challenges for social justice within career guidance in neoliberal times. Journal of the National Institute for Career Education and Counselling, 36(1), 12–19.

Rai, V. (2013). Labour market information for employers and economic immigrants in Canada: A country study. Centre for the Study of Living Standards.

Samnani, A. K., & Singh, P. (2016). Workplace bullying: Considering the interaction between individual and work environment. Journal of Business Ethics, 139(3), 537–549. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2653-x

Sandberg, J., & Alvesson, M. (2011). Ways of constructing research questions: Gap-spotting or problematization? Organization, 18(1), 23–44. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350508410372151

Saniter, N., & Siedler, T. (2014). The effects of occupational knowledge: Job information centers, educational choices, and labor market outcomes. The Institute for the Study of Labor.

Savickas, M. L. (1997). Career adaptability: An integrative construct for life-span, life-space theory. The Career Development Quarterly, 45(3), 247–259. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-0045.1997.tb00469.x

Selwyn, N. (2016). Is technology good for education? Polity Press.

Skinner, B. T. (2019). Choosing college in the 2000s: An updated analysis using the conditional logistic choice model. Research in Higher Education, 60(2), 153–183. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-018-9507-1

Slife, B. D., Williams, R. N., & Williams, R. N. (1995). What's behind the research?: Discovering hidden assumptions in the behavioral sciences. Sage.

Sultana, R. G. (2014). Pessimism of the intellect, optimism of the will? Troubling the relationship between career guidance and social justice. International Journal for Educational and Vocational Guidance, 14(1), 5–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10775-013-9262-y

Super, D. E. (1953). A theory of vocational development. American Psychologist, 8(5), 185. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0056046

Watts, A. G. (1977). Careers education in higher education: Principles and practice. British Journal of Guidance and Counselling, 5(2), 167–184. https://doi.org/10.1080/03069887708258112

Watts, A. G. (1996). Socio-political ideologies in guidance. In Watts, A. G., Law, B., Killeen, J., Kidd, J. M., & Hawthorn, R. (Eds.), Rethinking careers education and guidance: Theory, policy and practice. Routledge.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Staunton, T., Rogosic, K. Labour market information and social justice: a critical examination. Int J Educ Vocat Guidance 21, 697–715 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10775-021-09466-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10775-021-09466-3