Abstract

This study defines the conceptual structure of corporate entrepreneurship (CE) by looking at the terms scholars have used over the last 26 years of research. With the use of a co-word analysis, five distinctive dimensions of CE and the evolution of related key terms are identified: sustained regeneration, competitive advantage, external entrepreneurship, organizational rejuvenation, and domain redefinition. Over time scholars’ attention has shifted from strategy to entrepreneurship by highlighting the relevance of the terms ‘intrapreneurship’ and ‘entrepreneurial orientation’. Surprisingly, concepts related to strategic entrepreneurship and strategic renewal are less relevant than expected. Besides laying the ground for a shared conceptualization of CE, this study highlights how bibliomeitrics can contribute to decreasing conceptual ambiguity in emergent research fields, such as entrepreneurship. Implications for managers on how to strategically create and develop CE within different organizational settings are also discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Corporate entrepreneurship (CE) can be defined as “[…] the process by which teams within an established company conceive, foster, launch and manage a new business that is distinct from the parent company but leverages the parent’s assets, market position, capabilities or other resources” (Wolcott and Lippitz 2007; p. 75). In the struggling task to cope with the rapid pace of the world’s transformations, how firms handle CE is vital for their success. As such, the scientific relevance of CE has increased over time, especially in those fields of study related to entrepreneurship and strategy (Ginsberg and Hay 1994; Kuratko et al. 2015; Thornberry 2001).

As a research topic, CE has evolved dramatically over the last 40 years, during which definitions and research goals have proliferated (Corbett et al. 2013; Kuratko and Audretsch 2013; Lampe et al. 2020; Nason et al. 2015; Phan et al. 2009; Thornberry 2001). Kuratko and Morris (2018) used the concept of CE to describe entrepreneurial behaviours in established mid-sized and large organizations. They referred to CE as a primary strategy in all types of organizations, distinguishing three major components, namely, strategic entrepreneurship, corporate venturing, and entrepreneurial orientations. These components convey an idea of organizational transformation that can assume many different forms and shapes that, in turn, have given rise to multiple facets of CE.

Despite the efforts to refine its conceptualization, an overview of existing literature reviews (see “Appendix 1”) demonstrates that a universally accepted definition of CE is still lacking (Ireland et al. 2009; Narayanan et al. 2009; Nason et al. 2015). As a result of studies’ fragmentation, this topic emerges as highly controversial (Bouchard and Fayolle 2018; Nason et al. 2015). Covin and Miles (1999; p. 48) clearly emphasized this issue: “[…] when management theorists talk about corporate entrepreneurship, they are often talking about different phenomena.” Indeed, some authors have associated the term CE with intrapreneurship (Kuratko et al. 1990), internal CE (Burgelman 1983; Ginsberg and Hay 1994), corporate ventures (Ellis and Taylor 1987; Thornberry 2001), and new ventures (Roberts 1980). Others have conceptualized CE as a set of firm’s activities, including a new business/venturing activity, innovativeness, and self-strategic renewal (Covin and Miller 2014; Sharma and Chrisman 1999). Others have tried to determine theoretical relationships between innovation, entrepreneurship, strategy, and strategic entrepreneurship without however reaching a definitive conclusion on the conceptual boundaries of CE (Barringer and Bluedorn 1999; Di Stefano et al. 2010; Ireland et al. 2009; Kuratko and Morris 2018; Mazzei et al. 2017).

This inconclusiveness seems to be related to the evolution this concept has come through. Over the years, CE has been understood both as a unidimensional or multidimensional concept (i.e., Baier-Fuentes et al. 2018; Hayton and Cacciotti 2013; Liu and Tang 2020; Piñeiro-Chousa et al. 2020; Sassetti et al. 2018; Sharma and Chrisman 1999). A multidimensional construct is here intended as having a set of diverse but interwind dimensions emphasizing each a different conceptual shading but encompassing a meaningful theoretical abstraction (Law et al. 1998; MacKenzie et al. 2011). Tensions and criticisms about the conceptualization of CE have, then, intensified increasing fragmentation and causing a delay in research advancement. Without a clear and shared conceptualization of CE, indeed, our understanding of its antecedents, consequences and processual mechanisms can be hindered. Furthermore, the risk of producing non-cumulative knowledge as a result of the coexistence of separated conceptualizations of CE is likely to persist as one of the main critical issues of this topic (Ireland et al. 2009). These drawbacks prevent scholars from elaborating guidelines for managers, continuing to making CE one of the most problematic strategy to be implemented within organizations (Kreiser et al. 2019).

Against this scenario, we take the challenge and draw the conceptual structure of CE by relying on key terms that scholars have used to study CE over the last 26 years of research. The conceptual structure is envisioned as a spatial representation of how terms are related to one another to form subgroups, in which distances and primary links among terms are also estimated (Cobo et al. 2013; Small 1973). Key terms are thought to represent the shared knowledge within a community, and the progress of the field depends on a collective acceptance of their meanings (Koontz 1980). Therefore, we chose to focus our analysis on key terms because their systematic representation helps the field clarify what CE is and which dimensions shape its conceptual structure.

To perform this study, we relied on bibliometrics. In particular, we used a co-word analysis, defined as a computation of words’ co-occurrences in a corpus of data (Benavides-Velasco et al. 2013; Callon et al. 1983; Castriotta et al. 2019; Danvila-del-Valle et al. 2019; Ravikumar et al. 2015). Co-word analysis, when applied to keywords, is a powerful method that allowed us to investigate the relationships among key terms and their evolution over time. Furthermore, by following the methodological prescriptions of Zupic and Čater (2015) and by exploiting the VOSviewer (Van Eck and Waltman 2007) and an ad-hoc software developed with the Python language (using Numpy and MatPlotLib) features, we adopted co-word analysis as a platform on which to apply three complementary analytical techniques, namely: cluster analysis, science mapping, and pathfinder algorithm (Nerur et al. 2016; Van Eck et al. 2010; Van Eck and Waltman 2017). In so doing, we could achieve the following specific research goals: (a) define the fundamental dimensions of CE, (b) highlight the mutual relationships among these dimensions and their constituting key terms, (c) and, ultimately, identify the temporal salience of CE dimensions. As a resulting phase of this study, we elaborated on the current conceptualization of CE and highlighted future research avenues that connect the concept to contemporary socio-economic transformations. Therefore, this study contributes to addressing the need, as claimed in the literature, of delimiting those key variables that are able to adequately explain CE dynamics (Hornsby et al. 1993, 2002).

Overall, this study brings three contributions to the current literature. First, to our knowledge, this is the first study in CE to be performed by adopting a quantitative method that considers words as a source of information and that investigates the collective understanding of CE. Hence, the primary contribution of this work is building a unique framework that integrates the multiple CE perspectives from a semantic point of view. This achievement is relevant because it contrasts fragmentation without hyper simplifying the CE complexity. Hence, managers have a conceptual tool that identifies those dimensions that they should take into account when implementing CE within their organizations. Second, this study reviews co-occurring keywords and how they cluster to determine the conceptual distinctiveness and mutual relatedness of the emerged dimensions. This allowed us to propose five dimensions of CE: Sustained regeneration, Organizational rejuvenation, Competitive advantage, Domain redefinition, and External entrepreneurship. This result reduces CE’s conceptual ambiguity and suggests a bibliometrics key role in fine-grained conceptual analyses such as splitting and identifying sub-dimensions of multidimensional constructs. This analysis helped us to reveal lesser-explored dimensions of CE, namely Domain redefinition and External entrepreneurship, informing managers of the relevance of these dimensions in the CE implementation process. Lastly, in exploiting the co-word analysis distinctive features, this research expands the role of bibliometrics in entrepreneurship (see “Appendix 2”). This study shows that bibliometrics is extremely useful for identifying the dimensions that compose a construct, laying the ground for future research to use the conceptual structure or co-word analysis to develop and test the constitutive parts of theoretical constructs and decrease conceptual ambiguity in emergent research fields, such as entrepreneurship. Overall, in defining a more nuanced conceptualization of CE, this study helps managers to set a comprehensive strategy on how to implement a CE process within their organizations.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. We first expose the theoretical background of the CE domain and explain the methodology and the procedures adopted during data collection, analysis, and processing. We then move on to the results section, where we summarize our findings. A discussion follows to highlight future research avenues, the limitations, and the contributions of the study.

Theoretical background

Despite scholars’ efforts, research is far from providing a shared definition and a common consensus on CE, especially regarding the mechanisms through which organizations enact this process. With the fast pace of evolution of this research field, the concept of CE has been linked to a long series of neighbouring constructs. This diversity has resulted in a broad and multidimensional conceptualization of CE, which assumes different definitions and forms across studies (Corbett et al. 2013; Kuratko and Audretsch 2013; Lampe et al. 2020; Nason et al. 2015; Phan et al. 2009; Thornberry 2001). Yet, while this conceptual evolution has enriched the topic, it has also intensified the complexity of such a concept and yielded a lack of consensus of its conceptual boundaries (Kuratko and Audretsch 2013).

Regarding the several terms used to identify the concept of CE, we noticed that many of them are used interchangeably, and sometimes, without a clear identification of conceptual boundaries (Burgelman 1983; Chung and Gibbons 1997; Covin and Slevin 1991; Guth and Ginsberg 1990; Schendel 1990; Spann et al. 1988; Vesper 1984; Zahra 1995). This is the case of “corporate venturing” (i.e., Block and MacMillan 1993), “intrapreneurship” (i.e., Nielson et al. 1985), “internal entrepreneurship” (i.e., Jones and Butler 1992), “internal venturing” (i.e., Stopford and Baden-Fuller 1994), “strategic renewal” (i.e., Zahra 1993), “organizational renewal” (i.e., Kuratko 2007), “strategic entrepreneurship” (i.e., Morris et al. 2011), “organizational entrepreneurship” (i.e., Kuratko 2009), “sustained corporate regeneration” (i.e., Monsen and Boss 2009), “corporate domain redefinition” (i.e., Kuratko 2011), and “organizational rejuvenation” (i.e., Morris et al. 2011).

Regarding CE’s multidimensional nature, this is a problematic issue because there is inconclusiveness regarding its unidimensional or multidimensional structure, causing fragmentation in the field with overlapping or unrelated subfields of research. Furthermore, even when scholars agree in defining CE as a multidimensional construct, these dimensions do not overlap among studies (e.g., Di Stefano et al. 2010; Ferreira et al. 2016; Grégoire et al. 2006; Teixeira 2011) or are hierarchically misaligned (Lampe et al. 2020) (see “Appendix 2”). For instance, existing literature has shaped CE as a polycentric construct that encompasses two major phenomena: corporate venturing and strategic renewal (Guth and Ginsberg 1990). Corporate venturing concerns the various processes associated with new venture creation within existing organisations (Covin and Miles 1999; Morris et al. 2011; Narayanan et al. 2009). Notably, internal corporate venturing involves creating new businesses that generally reside within the corporate structure, while external corporate venturing includes young or early growth-stage businesses acquired by external parties (e.g., through licensing, acquisitions, joint ventures) (Sharma and Chrisman 1999). In contrast, strategic renewal entails the transformation of ongoing organisations by renewing the key ideas on which they are built (Guth and Ginsberg 1990) to simultaneously create and sustain a competitive advantage (Dess et al. 2003; Ireland et al. 2003). Additionally, there are also forms of cooperative venturing that include the creation of a new business entity through the cooperative efforts of two or more parent firms (Covin and Miles 2007; Morris et al. 2011).

Some authors associate strategic entrepreneurship with the strategic renewal concept (Klammer et al. 2017). Indeed, strategic entrepreneurship may or may not add a new business to the corporation (Covin and Kuratko 2010), and involve innovation initiatives resulting in areas as firm’s strategy, product offerings, served markets, internal organisation (i.e., structure, processes, and capabilities), or business model (Kuratko and Audretsch 2009; Morris et al. 2011). When arguing about strategic entrepreneurship, scholars also outline other related concepts such as sustained regeneration, domain redefinition, organizational rejuvenation, and business model reconstruction (Covin and Miles 1999; Miles et al. 2003; Phan et al. 2009). Sustained regeneration implies continuous innovations, and it represents the most frequently recognised CE form by scholars (Dess et al. 2003). Domain redefinition focuses on the firms proactivity in creating a new product market position that competitors have not recognised or have underserved (Covin and Miles 1999). Organizational rejuvenation focuses on the firm’s internal processes, structures, and capabilities to execute strategies, and shows that firms can become more entrepreneurial through processes and structures, as well as by introducing new product and/or entering new markets with existing products.

The CE concept has been associated to the intrapreneurship phenomenon (Bouchard and Fayolle 2018; Gawke et al. 2019), that refers to the Schumpeterian innovation approach of developing a new venture within an existing organisation, to exploit a new opportunity and create economic value (Parker 2011; Pinchot 1985). Intrapreneurship deals with four main distinct dimensions (Antoncic and Hisrich 2001; Neessen et al. 2019): new business venturing, that refers to the company introducing new potential solutions in its current market; innovativeness, that refers to the creation process of new services and technologies; self-renewal, that emphasises the strategic reorganisation and organizational change dynamics; proactiveness, that reflects entrepreneurial orientation to risk-taking initiatives. There is evidence that intrapreneurship helps managers to innovate, and to enhance their overall business performance (Antoncic and Hisrich 2001; Kuratko et al. 2015).

Further reflections emerge from CE relations with entrepreneurship and neighbouring research fields, such as innovation and strategy (Klein et al. 2010; Whittington 2004). For some authors, CE is an important potential growth strategy (Goodale et al. 2011; Lin and Lee 2011), or “a vision-directed, organization-wide reliance on entrepreneurial behaviour that purposefully and continuously rejuvenates the organization and shapes the scope of its operations through the recognition and exploitation of entrepreneurial opportunity” (Ireland et al. 2009: p. 21). In other words, a firm’s strategic intent to continuously and deliberately leverage entrepreneurial opportunities (Shane and Venkataraman 2000). CE seeks to renew established organisations through the utilisation of various innovation-based initiatives (Corbett et al. 2013), or of an original invention or idea into a commercially usable form that is new to the marketplace, and has the potential to transform the competitive environment as well as the organization. Over the years, several models have been proposed linking CE with entrepreneurial orientation (risk-taking, proactiveness and innovativeness), firm’s age and size (Phan et al. 2009; Pitelis and Teece 2009; Nason et al. 2015). Accordingly, the term has been typically associated with large public firms, but over time CE has become increasingly associated with many other organizational configurations (Minola et al. 2020; Narayanan et al. 2009; Nason et al. 2015; Phan et al. 2009).

This overlap among CE concepts has raised questions about the CE nature, by even disputing its usefulness in understanding organizational change processes. The lack of clear boundaries among its components has contributed to confusion in what this concept represents theoretically. By carrying out a systematic conceptual evolution study, we propose a semantic approach which helps identify clearly the conceptual boundaries of the topic, showing its dimensions, and serves the scope of highlighting possible solutions to converge on a more shared conceptualization of the topic.

Method

Co-word analysis

Co-word analysis is an established bibliometric approach widely used in scientometrics to map and interpret the conceptual structure of a discipline’s scientific knowledge (Andersen 2019; Baker et al. 2020; Benavides-Velasco et al. 2013; Callon et al. 1991; Dehdarirad et al. 2014; Gupta et al. 2019; Hallinger et al. 2020; Kumar et al. 2019; Li 2019; Li et al. 2017; Murgado-Armenteros et al. 2015; Ravikumar et al. 2015; Romo-Fernández et al. 2013). The conceptual structure is a representation of how elements as concepts/words are related to one another (Small 1999). This method aims to analyze the relationship among concepts/words, their role in substantive questions the research field asks, along with its boundaries (Cobo et al. 2011).

The co-word analysis draws upon the assumption that a paper’s keyword constitutes an adequate description of its content (Callon et al. 1983). Operationally, two words that co-occur within the same paper are an indication of their thematic connection (Cambrosio et al. 1993). Then, the presence of many co-occurrences around pairs of words contributes to forming a research theme (Ding et al. 2001).

Historically, co-word analysis, through the visualization of the conceptual structures, has had a transversal adoption with respect to the areas of business and management, finding application in the areas of strategy, management and innovation (Zupic and Čater 2015). It has also been adopted as a methodological tool to achieve multiple research goals. For example, in addition to detecting the main research topics of a body of literature or a research area, some researchers have exploited the method’s potential by extending the reflection of a key concept (Ronda-Pupo and Guerras-Martin 2012). Others have revealed the conceptual evolution of a research field by analyzing the definitions of a research area (Hernández-Linares et al. 2018) while others have contributed to the research by offering a better description and understanding of the conceptual differences between semantically similar constructs (Gupta et al. 2019).

Co-word analysis is one of the bibliometric analyses legitimized in the literature and characterized by a strong semantic focus. Nevertheless, the deepening of the other typologies of bibliometric analyses and the comparison with the co-word analysis is outside the scope of the present work (see Zupic and Čater 2015, for more insights).

Finally, it is worth underlining that in this work—by following the methodological prescriptions of Zupic and Čater (2015) and by exploiting the VOSviewer (Van Eck and Waltman 2007) and an ad-hoc software developed with the Python language (using Numpy and MatPlotLib) features—we adopted co-word analysis as a platform on which to apply three complementary analytical techniques: cluster analysis, science mapping, and pathfinder algorithm (Nerur et al. 2016; Van Eck and Waltman 2017). In the next paragraph, these techniques will be explained more in detail.

Science mapping techniques and software

By relying on previous bibliometric studies (Di Stefano et al. 2012; Zupic and Čater 2015) and consistent with our research goals of delimiting the field of CE conceptually, we applied three complementary analytical techniques: cluster analysis, science mapping, and pathfinder algorithm (Nerur et al. 2016; Van Eck and Waltman 2017).

VOSviewer is the software used to perform the co-word analysis. The advantage of using this software is that it provides a unified approach to clustering and mapping bibliometric networks. For this reason, it has been proposed by scientometrists as a valuable alternative to other statistical software in combining clustering and mapping techniques (Van Eck et al. 2010; Waltman et al. 2010). VOSviewer computes the distance between nodes according to their degree of similarity, yielding a more accurate result and visualization of findings (Van Eck and Waltman 2007). Also, VOSviewer performs a weighted and parametrized variant of the Louvain method for partitioning data into clusters (Waltman et al. 2010) and a variant of the well-known multidimensional scaling (MDS) technique called visualization of similarities (Van Eck and Waltman 2007). VOSviewer cluster analysis is well suited to finding similarities among subgroups in a field and attempts to find a structure in a set of proximity measures by producing a map in a two-dimensional space. Accordingly, similar items will appear closer in the map, and dissimilar ones are located far from each other (Leydesdorff and Vaughan 2006). Furthermore, VOSviewer has been adopted as a network visualization tool (Van Eck and Waltman 2017) to better identify the connections among terms and clusters (if any). In our study, it is worth pointing out that we ran the VOSviewer software by selecting the default parameters, specifically: (a) the association strength both as normalization method and similarity measure; (b) layout: attraction index = 2.00 and repulsion index = 1.00: (c) resolution of clustering = 1.00; (d) minimum cluster size 1.00; view: network. Please see Van Eck et al. (2010) and Van Eck and Waltman (2017) for more details.

To corroborate the network results and to strengthen the robustness of the cluster analysis results (Di Stefano et al. 2012; Zupic and Čater 2015), by means of an ad-hoc software developed with the Python language (using Numpy and MatPlotLib), we also applied a Pathfinder algorithm that reduces the matrix of co-occurrences to provide the most important links in a network to be found. To obtain the simplified network, the first choice is that only the weakest link (longest distance) is important when computing distances between concepts, and the second one implies that a specific path between two nodes can be removed if any other indirect path (between the same nodes) is found to be shorter (Schvaneveldt 1990). The resulting map (PFNet) shows a network in which keywords represent the nodes, while the edge between nodes represents the frequency with which they co-occurred and provides scholars with the opportunity to highlight dominant concepts and the strongest links among them.

Sample selection

Data retrieval

Data were retrieved from the Web of Science (WoS), which is among the world’s largest multidisciplinary databases of scientific literature (Bar-Ilan 2008). It is broadly adopted in bibliometric studies (Di Guardo et al. 2012; Hernández-Linares et al. 2018) because it balances the need for a more extensive literature coverage and provides advanced ad hoc tools for descriptive analyses of publication data (Romo-Fernández et al. 2013).

Our study covers 26 years of the field’s history, ranging from 1991 to 2017. Two reasons support this choice. Methodologically, it represents an adequate timeframe to describe the conceptual structure of a mature field (Andersen 2019; Nerur et al. 2008). Second, entrepreneurship literature grew steadily during the 1990s (Landström et al. 2012; Landström and Harirchi 2018) and was legitimized as an academic discipline only after 2000 (Meyer et al. 2014). Accordingly, we juxtaposed the observed publication history of CE with that of the entrepreneurship domain, and this might facilitate the comparability between the two kinds of literature.

To investigate the field’s evolution, the entire time frame was segmented according to three-time windows: 1991–2006, 2007–2011, and 2012–2017. Depending on the number of publications per year, we set the first period (1991–2006) as the longest, with 15 years, and the second (2007–2011) and third periods (2011–2017) each cover a time span of five years each (Dehdarirad et al. 2014).

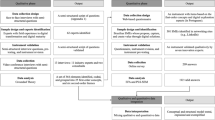

The selection of a representative sample of keywords involves following an iterative process to include all relevant contributions (see “Appendix 3”). This process, which is based on CE literature, allowed us to compose a search query with multiple terms (see “Appendix 4 and 5”). First, we extracted all the contributions containing the word CE in the titles, abstract, and authors’ keywords. Second, we screened this literature and selected all terms theoretically related to CE (Burgelman 1983; Chung and Gibbons 1997; Zahra 1991, 1995). Third, we limited the document type selection to scholarly journal articles and reviews written in English. This query yielded a preliminary set of 1251 filtered documents.

To ensure that only pertinent documents were selected, three independent coders manually verified the contents of titles, abstracts, authors’ keywords, and WoS-generated keywordsFootnote 1 (KeyWord Plus). The inter-rater agreement Fleiss K was 88.2% that represents an acceptable agreement among co-authors. As a result of this validation process, a small number of papers were excluded, thereby reducing the initial list to 1135 documents (see Fig. 1). To extract key terms from the selected documents, we used the authors’ keywords; when these keywords were not available, we used the KeyWord Plus provided by the WoS database (Zhang et al. 2015).

As shown in Table 1, 804 documents contained authors’ keywords, 279 documents contained KeyWord Plus, and 52 documents contained no keywords. As a result of the merger between author’s keywords and KeyWord Plus (hereafter ‘keyword’), we obtained a set of 2487 keywords.

Preprocessing

Keywords were first standardized by a vocabulary tool called Apache NLP 1.5.3 that uses natural language processing (Ding et al. 2001; Waltman et al. 2010). The Apache Openly library is a machine learning-based toolkit for the processing of natural language text. It supports the most common NLP tasks, such as tokenization, sentence segmentation, part-of-speech tagging, named entity extraction, chunking, parsing, and co-reference resolution. To identify macro-terms, the linguistic filters in this program identify the so-called noun phrases, convert plural forms of nouns into singular ones, calculate the noun phrases’ relevance, and cluster and map the phrases/terms. Furthermore, to promote a corroborative step of our analysis, we were supported by three independent coders in performing subsequent manual term processing; they received specific instructions to perform the standardization analysis (Ding et al. 2001; Zupic and Čater 2015) (see “Appendix 6”).

As a result of this preprocessing phase (the inter-rater agreement Fleiss K was 71.7%), the number of keywords decreased to 2043, among which 52 occurred at least 15 times (Aykroyd et al. 2019; Chandra 2018). These 52 keywords compose our unit of analysis and are paired into raw co-occurrences’ matrix (Small 1973). This 52 × 52 asymmetric matrix is the source from which we ran multivariate science mapping analysis (Waltman et al. 2010).

Results

The next paragraphs illustrate the findings related to our research goals. On the one hand, we define the fundamental dimensions of CE through the cluster analysis. On the other hand, we highlight the mutual relationships among key terms and dimensions via science mapping and pathfinder techiques. Lastly, by looking at the three time spans, we identify the temporal salience of these dimensions and related key terms.

Dimensions of CE

Cluster analysis

The cluster analysis allows the identification of five distinct clusters labelled by reflecting on the embodied key terms. As shown in Table 2, clusters are different not only in terms of the number of keywords they include but especially according to the topics they address. For instance, Cluster 1 (Sustained regeneration) is the largest one (15 keywords), while Cluster 5 (Domain redefinition) is the smallest one (6 keywords). Below, we briefly describe each cluster and discuss their positions on the map (Fig. 2).

Cluster 1—Sustained regeneration (red): This cluster is mostly concerned with the themes at the intersection between innovation, entrepreneurship, organizational studies, and strategy. Terms are primarily related to actions or dimensions that are useful to sustain a firm’s regeneration. The list of words shows that the terms innovation, entrepreneurship, and entrepreneurial orientation have the highest frequency. Focusing on the CE literature, the so-called intrapreneurship and corporate venturing dimensions characterize the group. Other related terms are technology, entrepreneurialism, family business, organizational culture, human capital, human resources, and venture capital. The cluster themes are strongly focused on small and medium-sized enterprises (SME), and startups.

Cluster 2—Competitive advantage (green): This cluster focuses on strategy and management areas, where performance and competitive advantage are strictly interconnected concepts. Strategic entrepreneurship construct, located in the proximity of the centre of the map, is the crucial CE dimension of the group. At the same time, the resource-based view is the most popular and adopted theoretical lens. Themes such as knowledge, decision making, corporate governance, mergers and acquisitions, and product development focus on multinational, established firms, and organizations in general.

Cluster 3—External entrepreneurship (blue): Themes in this cluster are theoretically positioned at the intersection between entrepreneurship and strategic areas, focusing on the external and exploratory conceptualization of entrepreneurship. The list of words shows that the multidimensional construct of CE appears with the highest frequency. This central theme is closely related to the following sub-themes: teams, opportunity identification, R&D, networks, strategic alliances, absorptive capacity, and international entrepreneurship.

Cluster 4—Organizational rejuvenation (yellow): This cluster is at the intersection between organizational and strategic studies. It mostly concerns themes dealing with dynamic capabilities, ambidexterity, and organizational change, which have the highest frequency. Strategic renewal belongs to this group with three other themes with lower frequency, namely, managers, behaviour, and organizational learning.

Cluster 5—Domain redefinition (purple): The central themes are theoretically positioned at the intersection between management and strategy areas. Strategic management is the most popular terms supported by sub-themes such as environment, economic growth, and market orientation.

Figure 2 provides a visual representation of both the cluster and science mapping solution along with network results, showing terms’ positions and their cluster affiliation. We interpreted the map by relying on the following rules. A keyword’s centrality is inferred depending on how closely it is positioned to the axes’ origin. This centrality means that the term is perceived to be of interest to many surrounding clusters. The distance between terms or groups or terms in the map represents differentiation or dissociation. A possible interpretation of the distance is that certain links have been neglected or overlooked by researchers. The circles’ size is due to the occurrences of a term in the sample. Apart from complementing Table 2, this figure helped us understand the connections between words and clusters, and terms’ relevance and centrality.

Science mapping and network analysis

To support the visualization of Fig. 2 with quantitative data, Table 3 reports the frequency of each term. This information facilitates the interpretation of the map. Specifically, it displays the most frequently used keywords of the sample. Science mapping and network analysis confirm that the most popular concepts are distributed in areas at the intersection with innovation, entrepreneurship, organizational studies, and strategy. The top 10 keywords with the highest frequency are performance (303), CE (257), innovation (164), entrepreneurship (144), entrepreneurial orientation (130), firms (106), management (83), SME (71), intrapreneurship (66), and competitive advantage (61).

In the centre of the map, we found the terms CE and performance. This latter is the most frequent term, indicating that a specific focus of CE is, indeed, firms’ performance. Other terms, such as strategic renewal, ambidexterity, and organizational learning appear as particularly central in the field, and they belong mostly to the Organizational rejuvenation cluster, confirming the relevance of organizational transformation in the CE conceptualizations. Strategic entrepreneurship is another central term in the map, even though it has a lower frequency compared to other terms occupying a semi-peripheral position, such as strategy and resources. Three terms appear particularly important, as suggested by their position on the map and their frequency. These terms are innovation, entrepreneurship, and entrepreneurial orientation, all of which belong to the Sustained regeneration cluster. This finding confirms the importance of innovation and entrepreneurial dimensions in the CE discourse.

By looking at the map’s boundaries, we can draw two lines and virtually connect them to reflect on the latent dimensions of CE (Fig. 3). On the left side of the map, we find terms related to innovation, such as innovativeness and risk-taking. On the right side of the map, we can find terms, such as absorptive capacity or mergers and acquisitions. These two extremes represent two important sides of innovation. On the one hand, we have the ingredients to innovate, and on the other hand, we have the strategic and organizational elements that allow a firm to innovate. On the upper side of the map, we can find those dimensions related to corporate venturing. They are represented by the terms entrepreneurialism, technology, venture capital, and startups. On the lower side of the map, we can find terms related to the business and management parts of CE, where the concept of competitive advantage is the most relevant.

The observation of these extremes allows the capture of the distinction among researchers who have focused their attention on the endogenous aspects of CE versus those who were mostly concerned with exogenous elements. Concerning the vertical dimension, it seems to oppose the entrepreneurial perspective to a managerial perspective.

Figure 4 shows the results based on the Pathfinder algorithm. The most significant link is between the CE and performance concepts. Performance, which is the most central concept in the map, is linked to entrepreneurial orientation and SME. These connections confirm the strong performance leveraging nature of CE, as it emphasizes its instrumental role that allows a firm to achieve its innovation outcome. Another important path is between performance and management. In this case, emphasis is placed on the strategical side of CE, where organizational dynamics, such as organizational change, are oriented to support the creation of a sustainable competitive advantage. Another important link is between performance and innovation. This link highlights CE’s role as a tool for innovating and the crucial relationship between corporate venturing, intrapreneurship, strategic alliances, and venture capital hub. Overall, these links show that studies on CE have been conducted mostly at the intersection of competitive advantage and sustained regeneration dimensions, where the organizational performance and the forms by which firms can innovate are the prevailing research foci. However, they also indicate that emergent topics have been enriching the CE conceptualization. In this specific case, the emphasis is on key terms related to risk-taking and network, which belong to external entrepreneurship and domain redefinition dimensions, respectively. Furthermore, it emerges that organizational issues are also critical nodes in the map, with organizational culture, intrapreneurship and human resources, all related via multiple links to other key terms in the map.

Evolution of CE

The investigation of CE’s evolution allows the authors to observe interesting details regarding how terms have changed their relevance over time, contributing to a profound change in CE’s conceptual structure. Table 4 shows the evolutions of the terms’ usage and the trends they have followed in each of the three examined temporal stages (1st: 1991–2006; 2nd: 2007–2011; 3rd: 2012–2017).

Some terms have been abandoned by researchers, and they appear only in the first period (1991–2006). They refer to organization and management issues, such as strategic management, organizational culture, and organizational learning. Among them is strategic renewal. If we look at the second period (2007–2011), we observe that 37% of keywords are new with respect to the first timespan. It is worth noticing the introduction of terms related to the entrepreneurial domain, such as entrepreneurship, entrepreneurial orientation, and opportunity identification, which are among the most frequent terms in recent research. Another important change is the introduction of the term small-medium enterprise, denoting an interest by CE researchers in contexts other than large firms. In the third period (2012–2017), this tendency is confirmed with the introduction of the keyword family business. In the same period, entrepreneurial terms increase their relevance, and the market orientation perspective and human resources are the new terms that denote research interest in looking both at the external and internal sides of an organization.

On the contrary, in CE conceptualization, some concepts have maintained their relevance over time. For example, performance-related concepts have a predominant position in all the three timespans, as well as the keyword innovation. Notably, the term intrapreneurship is becoming even more important in the last timespan with respect to the past, while CE’s relevance seems to remain stable. If we look at the strategic concepts, we can find that the term dynamic capabilities has gained position, whereas the relevance of competitive advantage has decreased substantially. The concept of strategic entrepreneurship steadily rose over the three periods.

Discussion

Based on a co-words analysis, this study delimited (1) the fundamental CE dimensions resulting from 26 years of research, (2) the relationships among these dimensions and the most frequently addressed terms used in association with the concept of CE, (3) and their evolution over time. By relying on these findings, we were able to identify the conceptual structure of CE that mirrors the collective scientific understanding of the topic (see Fig. 5) and an ensemble of future research avenue.

Regarding the conceptual structure, our results show that CE can be understood as an organizational phenomenon that describes possible actions and approaches towards innovation, which connect the individual, the organisation, and the environment levels of analysis. In addition, by confirming that CE is a multidimensional concept, this study allowed a clear dimensionality of CE to be found, which is composed of five dimensions, namely Sustained regeneration, Organizational rejuvenation, Competitive advantage, Domain redefinition, and External entrepreneurship. Each dimension includes specific terms encompassing the individual, organizational, and environmental levels of analysis, conveying the distinctiveness of these dimensions in CE’s conceptualization.

Overall, three fundamental results stem from this study. The first is that, according to the collective understanding of the concept, CE is a broader concept than that other studies have formulated. Second, organizational elements, rather than strategic ones, are emerging as central dimensions of CE. Third, the role of entrepreneurial dynamics and external entrepreneurship are gaining momentum in the mechanisms whereby CE can manifest. Below we discuss them.

Broadening the concept of CE

Findings revealed by cluster analysis confirm that CE’s main dimensions stemming from the scholars’ collective knowledge have many commonalities with those devised by Covin and Miles (1999). This insight allows considering these dimensions as legitimated constructs of the field. The Sustained regeneration dimension clearly emerges as a concept that describes the forms by which firms can innovate. The Domain redefinition is also discriminable, with its focus on creating new areas that the firm has the potential to exploit. Organizational rejuvenation is an identifiable component as well, and its meaning seems to conceptually overlap with the original idea of Covin and Miles (1999) to encompass the ways in which an organization might change to ensure its competitive advantage.

In addition to the dimensions exposed above, two crucial concepts emerge from our cluster analysis that extend CE’s current conceptualization: Competitive advantage and External entrepreneurship. First, the cluster of Competitive advantage is a transversal dimension of CE (Bierwerth et al. 2015; Covin and Miles 1999) because it represents the distinctiveness of the goal for which a firm realizes CE to adapt to changing environments. Its marginality in the map is interesting to note, together with the lower relevance than that expected of the strategic entrepreneurship construct. In line with the literature, a connection was expected to be found between these two constructs, which appear coherently in the same cluster in our study. Strategic entrepreneurship, in fact, is envisioned to represent the identification and exploitation of opportunities to simultaneously create and sustain a competitive advantage (Phan et al. 2009). Conceptually, it is understood as including all the components presented in Covin and Miles (1999)’s model (Kuratko and Audretsch 2013; Morris et al. 2011). However, a surprising detail is that the competitive advantage is not in the centre of the map and that strategic entrepreneurship, which is considered a basic component of CE (Kuratko et al. 2015), is used less frequently than expected. Furthermore, another notable detail is that strategic entrepreneurship is not in the same cluster as innovation or strategic renewal, but it seems to be more related to concepts dealing with firms’ strategy. This finding supports the idea that strategy-related concepts are less prominent in the current scholars’ representation than expected. Second, the cluster of External entrepreneurship emphasises the new entrepreneurial opportunities allowing an organization to transform. Terms such as opportunity recognition, networks, R&D, absorptive capacity are some examples of the elements denoting a scholars’ interest in working on antecedents of CE (Birkinshaw 1998; Sciascia et al. 2014). Importantly, the construct of CE is particularly associated with this cluster, which means that scholars working on this topic focus primarily on the sources of innovation that might determine the distinctiveness of CE, according to firms’ entrepreneurial spirit (García-Morales et al. 2014; Ireland et al. 2009) (Fig. 6).

By contrast with the previous literature analysis, our study shows that some dimensions regarded as central for CE emerge as less discriminable components of CE. In Covin and Miles (1999)’s idea, strategic renewal, for example, was thought to identify all the entrepreneurial acts by which a firm could alter how it competes by specifically redefining its relationship with the markets or industry competitors. According to the way in which scholars have addressed the topic, however, this component is merged with Organizational rejuvenation elements, thereby making strategic renewal less identifiable. This approach is more in accordance with the redefinition of CE advanced by Sharma and Chrisman (1999), which views strategic and organizational renewal as linked. Indeed, they define strategic renewal as follows: “[…] as corporate entrepreneurial efforts that result in significant changes to an organization’s business or corporate level strategy or structure. These changes alter pre-existing relationships within the organization or between the organization and its external environment and in most cases will involve some sort of innovation” (p. 19).

CE as an organizational phenomenon

If we look specifically at the terms scholars are using to address the topic, two important issues are worth considering. The first one is that the Sustained regeneration component embodies terms that indicate all the organizational situations in which CE can manifest. They include intrapreneurship, corporate venturing, startups, and, more generally, innovation, entrepreneurship, and entrepreneurial orientation. According to the scholars’ collective conceptualization, Sustained regeneration is not limited to introducing new services or products, but it also covers entrepreneurial behaviours and related elements, such as venture capital and entrepreneurialism.

The second issue concerns the component of Organizational rejuvenation. The relevance that scholars have attributed, especially in recent times, to the terms ambidexterity, dynamic capabilities, and more generally to organizational change is interesting to see. Surprisingly, a few key terms are grouped in this cluster. Nevertheless, organizational elements are essential and central for CE. A specific characteristic of these terms is that they are widespread in the map, and human resources, top management, and team, for instance, each belongs to a different cluster. Overall, these results suggest that organizational elements, especially those that are thought to create changes within an organization, deserve further exploration of the CE phenomenon (Ruiz and Coduras 2015).

The entrepreneurial nature of CE

A deeper look at the evolution of the terms shows that three important changes are worth discussing in CE’s conceptualization. First, CE is a topic that encompasses several academic disciplines, notably, innovation, entrepreneurship, organizational studies, and strategy. However, if we look at the most frequent concepts and their evolution over the three timespans, the centrality of the entrepreneurial component of CE clearly emerges. Thus, the relevance of strategy, which was high in the first period, has decreased in recent times, with authors’ attention being more focused on entrepreneurship.

A second interesting issue concerns the corporate size. Our findings confirm that authors are becoming increasingly interested in relating CE to SMEs (Bierwerth et al. 2015; Hagen et al. 2017; Heavey and Simsek 2013; Simsek et al. 2009). The keyword firm is becoming less used, whereas the frequency of SME is increasing. This result is consistent with Nason et al. (2015) and oversteps the idea of always seeing CE in relation to large corporations. In that respect, the relevance that CE is assuming for family business, a key term that becomes highly used only in the third timespan, is interesting (Pittino et al. 2017). This finding indicates that CE, as an entrepreneurial phenomenon, is a widespread concept that seems to apply to every corporate context, regardless of its size.

Third, our findings suggest that CE’s collective conceptualization does not overlap with the representation that views corporate venturing and strategic entrepreneurship as the two main components of CE. In this respect, some interesting details are that the phenomenon of intrapreneurship is unexpectedly more relevant than the concept of corporate venturing and that the former is becoming even more important than the latter if we look at the most recent timespan. Entrepreneurial orientation is another concept that deserves attention. Our study confirms that this concept has become more explicit in the study of CE (Ireland et al. 2009) and more central in current conceptualizations. Kuratko and Morris (2018), for example, state that corporate venturing, strategic entrepreneurship, and entrepreneurial orientation “[…] form the overall domain of CE. Building on these elements, it becomes possible to develop a CE strategy” (p. 46). According to the collective conceptualization, however, the entrepreneurial orientation component seems to be gaining momentum compared to other elements, signalling that a different scenario, in which the entrepreneurial part becomes even more relevant, might also be expected. It is worth noticing that also the external entrepreneurship dimension and domain redefinition are growing their relevance, denoting that the CE concept is including environmental components, usually disregarded in previous conceptualizations.

Avenues for future research

The concept of CE is instrumental for a firm to exploit its entrepreneurial potential. Kuratko and Morris (2018) showed how this concept’s study has been articulated in many forms and how researchers are continuously enriching the topic with different lenses. Compared to the new research lines that were recently outlined (Corbett et al. 2013; Sakhdari 2016), we have identified four issues that deserve further exploration.

In line with the relevance that the term intrapreneurship is acquiring in the current scenario, an interesting stream of research regards the exploitation of all the dimensions that might work as antecedents of entrepreneurial behaviours at the individual and organizational levels (Zampetakis et al. 2009). In this respect, the presence of keywords such as self-efficacy, social-cognitive theory, creativity, and leadership in association with CE in recent years is noteworthy. These issues reveal that the scholars’ community is also interested in investigating an organization’s internal resources to develop and sustain employees’ entrepreneurial mindset. According to this stream, studies focusing on Organizational rejuvenation might take advantage of works that have analysed the nascent behaviour outside established organizations (Davidsson and Honig 2003).

As emerged from the network analysis, our study confirms the centrality of a firm’s performance in CE’s theoretical discourse. However, in line with our findings, which showed that competitive advantage is a less central concept than expected, a possible future exploration is to understand whether and the extent to which this concept will constitute the distinctiveness of CE. A corporate entrepreneurial strategy is thought to guide organizations in their attempt to sustain advantage in the marketplace (Ireland et al. 2009). However, an organization might be entrepreneurial for many reasons (Kuratko and Morris 2018) and apply all CE forms to maintain its innovative reputation as an inherent characteristic of its organizational culture (Arz 2017). Von Hippel and Krogh (2003), for example, have shown how the open source sector embraces a private collective model of innovation in opposition to a private investment model, showing that being entrepreneurial and innovative is one of the best ways to solve technical problems and to advance the collective knowledge in a specific domain. The competitive advantage is not the heart of these approaches. However, what we know about CE remains valid and useful for an organization to be entrepreneurial. Furthermore, organizational entrepreneurship, in the form of the corporate venture or intrapreneurship, has been recently seen as a form of internal rebellion (Courpasson et al. 2016) by which employees confront the established structures, practices, and strategies in clear opposition to the management strategy. Future studies should then reflect theoretically on the connection between CE and competitive advantage and better understand its role in CE’s current and future conceptualization.

Another challenging research stream is to consider CE as a theoretical lens to better understand and develop new paradigms. For instance, according to Etzkowitz et al. (2000), an entrepreneurial university is any university that undertakes entrepreneurial activities to improve regional or national economic performance, as well as the university’s financial advantage and that of its faculty. We suggest that future studies on CE should stress the current tendencies and consider other diverse organizational contexts apart from large and established corporations. The investigation of CE’s applicability, as a theoretical lens in other contexts, might enhance our understanding of the mechanisms that surround an organization in its transformational entrepreneurial process. Our study on keywords suggests that scholars are recently investigating the relationship between CE and knowledge transfer, among others. Future studies should continue to maintain and strengthen this research avenue.

The results of our study confirm that CE might take many shapes in the pursuit of innovation and entrepreneurial behaviours (Yunis et al. 2017). In line with the importance attributed to the term innovation as a distinctive character of CE (Covin and Miles 1999), as confirmed in our work, we suggest that future research should explore this link further. A recent review by Sakhdari (2016) emphasized the importance of networks in enhancing CE. We believe that another important aspect to consider is the way in which organizations use networks. Specifically, we claim that scholars have disregarded the knowledge flows by which an organization strives to innovate. Studies working on open innovation, for example, which is mentioned here as a distributed innovation process based on purposively managed knowledge flows across organizational boundaries (Bogers et al. 2017; Chesbrough and Bogers 2014), have the potential to enrich the current conceptualization of CE and to develop the dimension that this study has labelled External entrepreneurship.

Limitations

The present work presents some limitations mostly related to the methodology adopted. The first methodological limitation is related to the source of information. Although the data were obtained from the WoS database, a legitimate tool by the scientific community to conduct bibliometric research (Zhang et al. 2015), WoS does not have complete quantitative coverage of publications. Future research may overcome this limitation by including additional databases (i.e., Scopus, Google Scholar, etc.). In relation to the composition of the unit of analysis, the dataset of this research consists only of articles and reviews extracted in the SCI, SSCI, A&H, and ESCI WoS database. Future studies should utilize more publication types, such as books, conference papers, patents, and reports (Bar-Ilan 2008), to obtain a complementary picture of the knowledge development.

Finally, we built our co-occurrence matrix by using only the authors’ keywords and WoS keywords. We are aware that papers published in the 1990s do not have author keywords. However, this restriction ensures that our analysis reflects the authors’ intended emphasis (Volery and Mazzarol 2015). In the future, research may be implemented by considering keywords from titles, abstracts, and/or full paper texts.

Theoretical and practical implications

This work has contributed to disentangle the CE’s internal structure by exploiting the distinctive features of the co-word analysis. While previous remarkable works used bibliometrics especially to investigate the intellectual structure of entrepreneurship as a research field (e.g., Grégoire et al. 2006; Meyer et al. 2014), to gain insights of its social structure (e.g., Teixeira 2011), or to look at specific branches of entrepreneurship, such as strategic entrepreneurship (Di Stefano et al. 2010), entrepreneurial cognition (Sassetti et al. 2018), international entrepreneurship (Baier-Fuentes et al. 2018), in this study, we used a co-word analysis to attain a fine-grained perspective on a theoretical construct. This result is relevant because it throws light on the role that bibliometrics plays in entrepreneurship, and in general, to define the conceptual structure of multidimensional constructs. Bibliometrics, indeed, besides offering macro overviews of research fields (Zupic and Čater 2015) provides useful techniques to explore fine details of theoretical concepts. We believe that using bibliometrics to elucidate a construct dimensionality is relevant for three important reasons. First, a fragmented conceptualization delays advancement in research because the same questions may be repeatedly tested with different labels, duplicating studies (Howard and Crayne 2019). Second, fragmentation amplifies dimensionality ambiguity, hindering the identification of conceptual distinctiveness among similar constructs. This makes it difficult for scholars to identify relevant and less relevant issues to enhance a better understanding of theoretical constructs. Third, misconceptions about a theoretical construct prevent scholars from identifying clear managerial implications, reducing the impact of a research field in society. In entrepreneurship studies, this feature might be vital to address conceptual ambiguities that still characterise the field and the term itself of entrepreneurship (McMullen et al. 2020).

Furthermore, our analysis has emphasised that bibliometrics brings agile tools and corroborates methodological procedures that support current protocols to define multidimensional constructs. In reviewing the authors keywords through a co-word analysis, we gathered the most frequently occurred terms associated with the study of CE underscoring the relations between them. In so doing, we have disentangled the inconclusive conceptualisation of CE by rooting our analysis on a quantitative technique that can take into account a large amount of data to determine multidimensionality. Since keywords can be considered a proxy of experts’ opinion regarding the dimensions that compose a theoretical construct, our choice to use only authors’ keywords has resulted in being particularly pertinent to our aim of disentangling CE’s conceptual structure. Then, current protocols of multidimensionality investigation, which are based mostly on collecting information from experts and literature reviews (e.g., Dekker et al. 2015; Verčič et al. 2016), might be complemented through bibliometric methods.

Besides its methodological contribution, this study has three principal theoretical implications that also have significant impacts at the practical level. First, we have integrated different multidimensional components of CE in a unique framework that clarifies what a manager should take into account to enact a corporate entrepreneuring process. The relevance of implementing CE processes in all types of organizations is well acknowledged by academics and managers (Minola et al. 2020). CE, however, “[…] remains on the knowledge frontier because the actual implementation of this strategy remains a challenge for many organizations” (Kreiser et al. 2019; p. 1). The conceptual fragmentation of CE makes its implementation even more complicated, adding confusion to complexity. In contrast with previous studies that have reduced CE to two overall dimensions, such as corporate venture and strategic entrepreneurship (e.g., Kuratko and Covin 2015; Morris et al. 2011) in order to rationalize its conceptual fragmentation, we have tried to sharpen the concept without reducing its complexity. Summarizing, this study provides managers with a conceptual tool composed of five dimensions (see Fig. 5) indicating that: CE can be implemented with different forms (sustained regeneration) to develop an organizational distinctiveness (competitive advantage), for which organizational requirements, such as dynamic capabilities, should be developed (organizational rejuvenation); managers should create new areas that the firm has the potential to exploit (domain redefinition), knowing that different external sources are available to identify new entrepreneurial opportunities (external entrepreneurship). This approach guides managers on how to strategically create and develop CE within different organizational settings.

Second, this study has revealed that the external dimension, which is an unexplored area in CE, is also fundamental to implement a CE process successfully. In their model of Corporate Entrepreneuring process, Hornsby et al. (1993, p. 33) affirm that “The decision to act intrapreneurially occurs as a result of an interaction between organizational characteristics, individual characteristics, and some kind of precipitating event. The precipitating event provides the impetus to behave intrapreneurially when other conditions are conducive to such behavior.” According to this model, precipitating events might have both an environmental or organizational origin. In extending this perspective, our study suggests that the external dimension of CE is increasing in relevance as a result of market and society mutations. Therefore, managers require a specific approach to handle with this external dimension, which differs from that used to handle internal organizational issues, usually focused on evaluating, for instance, work discretion, rewards/reinforcement, and sufficient time (van Wyk and Adonisi 2012). Therefore, to assess an organizational readiness to enact CE implementation, current tools should contemplate external organizational issues to help managers to build a comprehensive strategy of CE.

Third, CE is not only a strategy to enhance an organization’s competitive advantage, a term that, according to our study, is becoming marginal in the CE discourse. Instead, it is also a tool to exploit internal talents and motivate employees to innovate and be committed to their organization. This assures a continuous organization’s capacity to innovate (Damanpour 1991, 2017). Managers of organizations at broader levels (e.g., multinational, incumbent firms) are generally oriented to competitive advantage, thus, interested in looking for their distinctive performance in ever-changing business environments (Audretsch and Lehmann 2006). Nevertheless, although highly interconnected to strategy and management fields, other elements of CE should be taken into more significant consideration. These elements encompass the cultural and learning elements of CE, clearly represented in the organizational rejuvenation dimension, which occupies a central position in our conceptual representation of CE.

Notes

Keywords assigned by the WoS database, the so-called “KeyWord Plus”.

References

Andersen, N. (2019). Mapping the expatriate literature: A bibliometric review of the field from 1998 to 2017 and identification of current research fronts. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 1–38.

Antoncic, B., & Hisrich, R. D. (2001). Intrapreneurship: Constructive refinement and cross-cultural validation. Journal of Business Venturing, 16(5), 495–527.

Arz, C. (2017). Mechanisms of organizational culture for fostering corporate entrepreneurship: A systematic review and research agenda. Journal of Enterprising Culture, 25(4), 361–409.

Audretsch, D. B., & Lehmann, E. (2006). Entrepreneurial access and absorption of knowledge spillovers: Strategic board and managerial composition for competitive advantage. Journal of Small Business Management, 44(2), 155–166.

Aykroyd, R. G., Leiva, V., & Ruggeri, F. (2019). Recent developments of control charts, identification of big data sources and future trends of current research. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 144, 221–232.

Baden-Fuller, C. (1995). Strategic innovation, corporate entrepreneurship and matching outside-in to inside-out approaches to strategy research 1. British Journal of Management, 6, S3–S16.

Baier-Fuentes, H., Cascón-Katchadourian, J., Sánchez, Á. M., Herrera-Viedma, E., & Merigó, J. (2018). A bibliometric overview of the international journal of interactive multimedia and artificial intelligence. International Journal of Interactive Multimedia and Artificial Intelligence, 5(3), 9–16.

Baker, H. K., Pandey, N., Kumar, S., & Haldar, A. (2020). A bibliometric analysis of board diversity: Current status, development, and future research directions. Journal of Business Research, 108, 232–246.

Bar-Ilan, J. (2008). Which h-index? A comparison of WoS, Scopus and Google Scholar. Scientometrics, 74(2), 257–271.

Barringer, B. R., & Bluedorn, A. C. (1999). The relationship between corporate entrepreneurship and strategic management. Strategic Management Journal, 20(5), 421–444.

Benavides-Velasco, C. A., Quintana-García, C., & Guzmán-Parra, V. F. (2013). Trends in family business research. Small Business Economics, 40, 41–57.

Bierwerth, M., Schwens, C., Isidor, R., & Kabst, R. (2015). Corporate entrepreneurship and performance: A meta-analysis. Small Business Economics, 45, 255–278.

Birkinshaw, J. (1998). Corporate entrepreneurship in network organizations: How subsidiary initiative drives internal market efficiency. European Management Journal, 16(3), 355–364.

Block, Z., & MacMillan, I. (1993). Corporate venturing: Creating new businesses within the firm. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

Bogers, M., Zobel, A. K., Afuah, A., Almirall, E., Brunswicker, S., Dahlander, L., et al. (2017). The open innovation research landscape: Established perspectives and emerging themes across different levels of analysis. Industry and Innovation, 24(1), 8–40.

Bouchard, V., & Fayolle, A. (2018). Corporate entrepreneurship. London: Routledge.

Burgelman, R. A. (1983). Corporate entrepreneurship and strategic management: Insights from a process study. Management Science, 29(12), 1349–1364.

Callon, M., Courtial, J. P., & Laville, F. (1991). Co-word analysis as a tool for describing the network of interactions between basic and technological research: The case of polymer chemsitry. Scientometrics, 22(1), 155–205.

Callon, M., Courtial, J. P., Turner, W. A., & Bauin, S. (1983). From translations to problematic networks: An introduction to co-word analysis. Social Science Information, 22(2), 191–225.

Cambrosio, A., Limoges, C., Courtial, J. P., & Laville, F. (1993). Historical scientometrics? Mapping over 70 years of biological safety research with coword analysis. Scientometrics, 27(2), 119–143.

Castriotta, M., Loi, M., Marku, E., & Naitana, L. (2019). What’s in a name? Exploring the conceptual structure of emerging organizations. Scientometrics, 118(2), 407–437.

Chandra, Y. (2018). Mapping the evolution of entrepreneurship as a field of research (1990–2013): A scientometric analysis. PLoS ONE, 13(1), e0190228.

Chesbrough, H. W., & Bogers, M. (2014). Explicating open innovation: Clarifying an emerging paradigm for understanding innovation. In H. W. Chesbrough, W. Vanhaverbeke, & J. West (Eds.), New frontiers in open innovation (pp. 3–28). UK: Oxford University Press.

Chung, L. H., & Gibbons, P. T. (1997). Corporate entrepreneurship the roles of ideology and social capital. Group and Organization Management, 22(1), 10–30.

Cobo, M. J., Chiclana, F., Collop, A., de Ona, J., & Herrera-Viedma, E. (2013). A bibliometric analysis of the intelligent transportation systems research based on science mapping. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems, 15(2), 901–908.

Cobo, M. J., López-Herrera, A. G., Herrera-Viedma, E., & Herrera, F. (2011). An approach for detecting, quantifying, and visualizing the evolution of a research field: A practical application to the fuzzy sets theory field. Journal of Infometrics, 5(1), 146–166.

Corbett, A., Covin, J. G., O’Connor, G. C., & Tucci, C. L. (2013). Corporate entrepreneurship: State-of-the-art research and a future research agenda. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 30(5), 812–820.

Courpasson, D., Dany, F., & Martí, I. (2016). Organizational entrepreneurship as active resistance: A struggle against outsourcing. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 40(1), 131–160.

Covin, J. G., Ireland, R. D., & Kuratko, D. F. (2003). Exploring and exploitation functions of corporate venturing. In Best paper proceedings: Academy of management, Annual Meeting, Seattle, WA.

Covin, J. G., & Kuratko, D. F. (2010). The concept of corporate entrepreneurship. In Encyclopedia of technology and innovation management.

Covin, J. G., & Miles, M. L. (1999). Corporate entrepreneurship and the pursuit of competitive advantage. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 23(3), 47–63.

Covin, J., & Miles, M. P. (2007). The strategic use of corporate venturing. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 31(2), 183–207.

Covin, J. G., & Miller, D. (2014). International entrepreneurial orientation: Conceptual considerations, research themes, measurement issues, and future research directions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 38(1), 11–44.

Covin, J. G., & Slevin, D. P. (1991). A conceptual model of entrepreneurship as firm behavior. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 16(1), 7–25.

Damanpour, F. (1991). Organizational innovation: A meta-analysis of effects of determinants and moderators. Academy of Management Journal, 34(3), 555–590.

Damanpour, F. (2017). Organizational innovation. Business and Management. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190224851.013.19.

Danvila-del-Valle, I., Estévez-Mendoza, C., & Lara, F. J. (2019). Human resources training: A bibliometric analysis. Journal of Business Research, 101, 627–636.

Davidsson, P., & Honig, B. (2003). The role of social and human capital among nascent entrepreneurs. Journal of Business Venturing, 18(3), 301–331.

De Vita, L., Mari, M., & Poggesi, S. (2014). Women entrepreneurs in and from developing countries: Evidences from the literature. European Management Journal, 32(3), 451–460.

Dehdarirad, T., Villarroya, A., & Barrios, M. (2014). Research trends in gender differences in higher education and science: A co-word analysis. Scientometrics, 101, 273–290.

Dekker, J., Lybaert, N., Steijvers, T., & Depaire, B. (2015). The effect of family business professionalization as a multidimensional construct on firm performance. Journal of Small Business Management, 53(2), 516–538.

Dess, G. G., Ireland, R. D., Zahra, S. A., Floyd, S. W., Janney, J. J., & Lane, P. J. (2003). Emerging issues in corporate entrepreneurship. Journal of Management, 29(3), 351–378.

Di Guardo, M. C., Galvagno, M., & Cabiddu, F. (2012). Analysing the intellectual structure of e-service research. International Journal of E-Services and Mobile Applications (IJESMA), 4(2), 19–36.

Di Stefano, G., Gambardella, A., & Verona, G. (2012). Technology push and demand pull perspectives in innovation studies: Current findings and future research directions. Research Policy, 41(8), 1283–1295.

Di Stefano, G., Peteraf, M., & Verona, G. (2010). Dynamic capabilities deconstructed: A bibliographic investigation into the origins, development, and future directions of the research domain. Industrial and Corporate Change, 19(4), 1187–1204.

Ding, Y., Chowdhury, G. G., & Foo, S. (2001). Bibliometric cartography of information retrieval research by using co-word analysis. Information Processing and Management, 37(6), 817–842.

Ellis, R. J., & Taylor, N. (1987). Specifying entrepreneurship. Frontiers of Entrepreneurship Research, 7, 527–542.

Etzkowitz, H., Webster, A., Gebhardt, C., & Terra, B. R. C. (2000). The future of the university and the university of the future: Evolution of ivory tower to entrepreneurial paradigm. Research Policy, 29(2), 313–330.

Ferreira, J., Fernandes, C., & Ratten, V. (2016). A co-citation bibliometric analysis of strategic management research. Scientometrics, 109(1), 1–32.

García-Morales, V. J., Bolívar-Ramos, M. T., & Martín-Rojas, R. (2014). Technological variables and absorptive capacity’s influence on performance through corporate entrepreneurship. Journal of Business Research, 67(7), 1468–1477.

Gawke, J. C., Gorgievski, M. J., & Bakker, A. B. (2019). Measuring intrapreneurship at the individual level: Development and validation of the Employee Intrapreneurship Scale (EIS). European Management Journal, 37(6), 806–817.

Ginsberg, A., & Hay, M. (1994). Confronting the challenges of corporate entrepreneurship: Guidelines for venture managers. European Management Journal, 12(4), 382–389.

Goodale, J. C., Kuratko, D. F., Hornsby, J. S., & Covin, J. G. (2011). Operations management and corporate entrepreneurship: The moderating effect of operations control on the antecedents of corporate entrepreneurial activity in relation to innovation performance. Journal of Operations Management, 29(1), 116–127.

Grégoire, D. A., Noel, M. X., Déry, R., & Béchard, J. P. (2006). Is there conceptual convergence in entrepreneurship research? A co–citation analysis of frontiers of entrepreneurship research, 1981–2004. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 30(3), 333–373.

Gupta, R., Mejia, C., & Kajikawa, Y. (2019). Business, innovation and digital ecosystems landscape survey and knowledge cross sharing. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 147, 100–109.

Guth, W. D., & Ginsberg, A. (1990). Guest editor’s introduction. Strategic Management Journal, 11, 5–15.

Hagen, B., Zucchella, A., Larimo, J., & Dimitratos, P. (2017). A taxonomy of strategic postures of international SMEs. European Management Review, 14(3), 265–285.

Hallinger, P., Gümüş, S., & Bellibaş, M. Ş. (2020). ‘Are principals instructional leaders yet?’A science map of the knowledge base on instructional leadership, 1940–2018. Scientometrics, 122(3), 1629–1650.

Hayton, J. C., & Cacciotti, G. (2013). Is there an entrepreneurial culture? A review of empirical research. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 25(9–10), 708–731.

Heavey, C., & Simsek, Z. (2013). Top management compositional effects on corporate entrepreneurship: The moderating role of perceived technological uncertainty. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 30(5), 837–855.

Hernández-Linares, R., Sarkar, S., & Cobo, M. J. (2018). Inspecting the Achilles heel: A quantitative analysis of 50 years of family business definitions. Scientometrics, 115, 929–951.

Hitt, M. A., Ireland, R. D., Camp, S. M., & Sexton, D. L. (2001). Strategic entrepreneurship: Entrepreneurial strategies for wealth creation. Strategic Management Journal, 22(6–7), 479–491.

Hjorth, D. (2005). Organizational entrepreneurship: With De Certeau on creating heterotopias (or spaces for play). Journal of Management Inquiry, 14(4), 386–398.

Hornsby, J. S., Kuratko, D. F., & Zahra, S. A. (2002). Middle managers’ perception of the internal environment for corporate entrepreneurship: Assessing a measurement scale. Journal of Business Venturing, 17(3), 253–273.

Hornsby, J. S., Naffziger, D. W., Kuratko, D. F., & Montagno, R. V. (1993). An interactive model of the corporate entrepreneurship process. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 17(2), 29–37.

Howard, M. C., & Crayne, M. P. (2019). Persistence: Defining the multidimensional construct and creating a measure. Personality and Individual Differences, 139, 77–89.

Ireland, R. D., Covin, J. G., & Kuratko, D. F. (2009). Conceptualizing corporate entrepreneurship strategy. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 33(1), 19–46.

Ireland, R. D., Hitt, M. A., & Sirmon, D. G. (2003). A model of strategic entrepreneurship: The construct and its dimensions. Journal of Management, 29(6), 963–989.

Jennings, D. F., & Lumpkin, J. R. (1989). Functioning modeling corporate entrepreneurship: An empirical integrative analysis. Journal of Management, 15(3), 485–502.

Jones, G., & Butler, J. (1992). Managing internal corporate entrepreneurship: An agency theory perspective. Journal of Management, 18(4), 733–749.

Khasseh, A. A., Soheili, F., Moghaddam, H. S., & Chelak, A. M. (2017). Intellectual structure of knowledge in iMetrics: A co-word analysis. Information Processing and Management, 53(3), 705–720.

Klammer, A., Gueldenberg, S., Kraus, S., & O’Dwyer, M. (2017). To change or not to change—Antecedents and outcomes of strategic renewal in SMEs. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 13(3), 739–756.

Klein, P. G., Mahoney, J. T., McGahan, A. M., & Pitelis, C. N. (2010). Toward a theory of public entrepreneurship. European Management Review, 7(1), 1–15.

Koontz, H. (1980). The management theory jungle revisited. Academy of Management Review, 5(2), 175–188.

Kreiser, P. M., Kuratko, D. F., Covin, J. G., Ireland, D., & Hornsby, J. S. (2019). Corporate entrepreneurship strategy: Extending our knowledge boundaries through configuration theory. Small Business Economics. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-019-00198-x.

Kumar, S., Sureka, R., & Colombage, S. (2019). Capital structure of SMEs: A systematic literature review and bibliometric analysis. Management Review Quarterly, 1–31.

Kuratko, D. F. (2007). Entrepreneurial leadership in the 21st century. Journal of Leadership and Organizational Studies., I13(4), 1–11.

Kuratko, D. F. (2009). The entrepreneurial imperative of the 21st century. Business Horizons, 52(5), 421–428.

Kuratko, D. F. (2011). Entrepreneurship theory, process, and practice in the 21st century. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business, 13(1), 8–17.

Kuratko, D. F., & Audretsch, D. B. (2009). Strategic entrepreneurship: Exploring different perspectives of an emerging concept. Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice, 33(1), 1–17.