Abstract

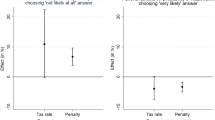

According to the world values survey, citizens justification of tax evasion varies widely across individuals and countries. We explore in this paper how justification of tax evasion covaries across individuals and countries with measures of government quality and the survey respondents own perceptions of the institutional quality. We study three proxies for individuals assessment of institutional quality, namely confidence in government, in civil service and in justice. We find only weak evidence that better assessments of the quality of government institutions are associated with less justification of tax evasion.

Source: Own computations based on WVS

Source: Own computations based on WVS

Source: Own computations based on WVS

Source: Own computations based on WVS

Source: Own computations based on WVS

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The 56 countries considered were: Algeria, Azerbaijan, Argentina, Australia, Armenia, Brazil, Belarus, Chile, China, Taiwan, Colombia, Cyprus, Ecuador, Estonia, Georgia, Ghana, Hong Kong, India, Iraq, Japan, Jordan, Kazakhstan, South Korea, Kuwait, Kyrgyzstan, Lebanon, Libya, Malaysia, Mexico, Morocco, Netherlands, Nigeria, Pakistan, Palestine, Peru, Philippines, Poland, Romania, Russia, Rwanda, Slovenia, South Africa, Zimbabwe, Singapore, Spain, Sweden, Thailand, Trinidad and Tobago, Tunisia, Turkey, Ukraine, Egypt, United States, Uruguay, Uzbekistan and Yemen.

We follow the literature on tax morale in recoding this variable. Frey and Torgler (2007), Strei (2013), Torgler (2005), Torgler and Schneider (2007) use a four-point scale. For convenience and ease of interpretation of the results, we use a two point scale as, among others, Alm and Torgler (2006), Daude (2012), Doerrenberg and Peichl (2013), Gerstenblüth (2012), Halla (2012), Heinemann (2010). The cutoff point at the first category is also the most commonly used in the tax morale literature. We provide some justification of this choice below, in Sect. 2.2.

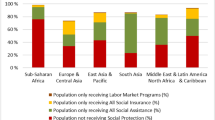

Notice however that the countries included in the WVS are not necessarily fully representative of each region. Countries by region (World Bank classification): East Asia and Pacific: Australia, China, Hong Kong, Japan, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore, South Korea, Taiwan and Thailand. Europe & Central Asia: Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Cyprus, Estonia, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Netherlands, Poland, Romania, Russia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Turkey, Ukraine and Uzbekistan. Latin America and Caribbean: Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Mexico, Peru, Trinidad and Tobago, and Uruguay. Middle East and North Africa: Algeria, Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Libya, Morocco, Palestine, Tunisia and Yemen. North America: United States. South Asia: India and Pakistan. Sub-Saharan Africa: Ghana, Nigeria, Rwanda, South Africa and Zimbabwe. (3) Countries by income group (World Bank classification): High income: Australia, Chile, Cyprus, Estonia, Hong Kong, Japan, Kuwait, Netherlands, Poland, Russia, Singapore, Slovenia, South Korea, Spain, Sweden, Taiwan, Trinidad and Tobago, United States and Uruguay. Upper middle income: Algeria, Argentina, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Brazil, China, Colombia, Ecuador, Iraq, Jordan, Kazakhstan, Lebanon, Libya, Malaysia, Mexico, Peru, Romania, South Africa, Thailand, Tunisia and Turkey. Lower middle income: Armenia, Egypt, Georgia, Ghana, India, Kyrgyzstan, Morocco, Nigeria, Pakistan, Palestine, Philippines, Ukraine, Uzbekistan and Yemen. Low income: Rwanda and Zimbabwe. Data is not weighted by the population of each country (all countries have the same weight).

Cruces et al. (2013) show evidence of systematic biases in this regard, and explain them in terms of groups of reference.

The regressors “Income” and “Pride” are not standard in this literature, though.

Columns (1)–(4) in the first panel are just the odds ratio version of the regressions in Table 2. Because the WVS is an unbalanced panel, the observations included in a regression may vary when a regressor is added. To avoid this sort of missing data effects in our estimations, we estimated all models in each panel using the same sample, i.e. the largest sample that contains all the regressors used in any estimation in each panel.

References

Alm, J., & Torgler, B. (2006). Culture di erences and tax morale in the United States and in Europe. Journal of Economic Psychology, 27, 224–246.

Cruces, G., Pérez-Truglia, R., & Tetaz, M. (2013). Biased perceptions of income distribution and preferences for redistribution: Evidence from a survey experiment. Journal of Public Economics, 98, 100–112.

Daude, C. (2012). What drives tax morale? Tech. rep. OECD.

Doerrenberg, P., & Peichl, A. (2013). Progressive taxation and tax morale. Public Choice, 155, 293–316.

Feld, L. P., & Frey, B. S. (2002). Trust breeds trust: How taxpayers are treated. Economics of Governance, 3(2), 87–99.

Frey, B. S., & Torgler, B. (2007). Tax morale and conditional cooperation. Journal of Comparative Economics, 35, 136–159.

Gerstenblüth, M., et al. (2012). How do inequality a ect tax morale in Latin America and Caribbean? Revista de Economía del Rosario, 15.2, 123–135.

Halla, M. (2012). Tax morale and compliance behavior: First evidence on a causal link. The B.E. Journal of Economic Analysis and Policy 12(1), Article 13.

Heinemann, F. (2010). Economic crisis and morale. European Journal of Law and Economics, 32, 35–49.

Inglehart, R., et al. (2018). World Value Survey wave 6 (2010–2014). Version v2018-09-12.

Kaufmann, D., Kraay, A., & Mastruzzi, M. (2009). Governance matters VIII: Aggregate and individual governance indicators, 1996–2008. Washington: The World Bank.

Luttmer, E. F. P., & Singhal, M. (2014). Tax morale. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 28(4), 149–168.

Perry, G., et al. (2007). Informality, exit and exclusion. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

Rabe-Hesketh, S., & Skrondal, A. (2012). Multilevel and longitudinal modeling using stata (3rd ed.). College Station: STATA Press.

Sandmo, A. (2005). The theory of tax evasion: A retrospective view. National Tax Journal, 48(4), 643–663.

Slemrod, J. (2003). Trust in Public Finance. In S. Cnossen & H.-W. Sinn (Eds.), Public finance and public policy in the new century (pp. 49–88). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Slemrod, J. (2007). Cheating ourselves: The economics of tax evasion. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 21(1), 25–48.

Strei. (2013). The effect of German reunification on tax morale and the influence of preferences for income equality and government responsibility. In The public purpose XI, (pp. 115–141).

The World Bank. (2014). The worldwide governance indicators. Version 2014-09-26. http://info.worldbank.org/governance/wgi/index.aspx#home.

Torgler, B. (2005). Tax morale and direct democracy. European Journal of Political Economy, 21, 525–531.

Torgler, B., & Schneider, B. R. (2007). What shapes attitudes toward paying taxes? Evidence from multicultural European countries. Social Science Quarterly, 88(2), 443–470.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

We received useful comments to a previous paper, of which this is an offspring, from participants at the Jornadas del Banco Central del Uruguay; Jornadas internacionales de finanzas públicas (Universidad Nacional de Córdoba, Argentina), the 16th SAET Conference on Current Trends in Economics 2016, PET 16 Rio (Association for Public Economic Theory), the 2016 RIDGE-LACEA workshop on political economy, the 2016 LACEA-LAMES meeting and the 2017 World Congress of the International Economic Association. Comments received at seminars at UdelaR, Universidad de San Andrés, UCEMA and UCUDAL were also very useful in revising this paper. This paper also benefited from comments received from CPEC anonymous referees and from the editor, professor Roger Congleton. The usual disclaimer applies.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Forteza, A., Noboa, C. Perceptions of institutional quality and justification of tax evasion. Const Polit Econ 30, 367–382 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10602-019-09287-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10602-019-09287-1