Introduction

The expert authority of international bureaucraciesFootnote 1 – an authority ascribed to them as providers of expertise-based recommendations – has been widely discussed in the literature on international organisations (IOs).Footnote 2 Scholars argue that this authority constitutes the ‘heart of bureaucratic power’ of IOs and enables them to influence both international and national policy.Footnote 3 However, expert authority also rests on a social relationship between an authority holder and a subordinate. In the case of international bureaucracies, such relationships are characterised by substantial yet insufficiently understood variation in the authority ascribed to a bureaucracy by its audience, that is, by the addressees of its advice. We therefore ask: What explains the variation in the expert authority of international bureaucracies among national addressees?

This question is relevant in light of strong indications that variations exist that cannot be explained based on formal competences alone.Footnote 4 While recent research has made impressive inroads into the study of international authority, including its variation over time and among IOs,Footnote 5 much of this research has focused on the formal delegation of tasks and responsibilities, which we refer to as ‘de jure expert authority’. Almost all IO bureaucracies have gained substantial mandates to provide expertise in recent years, including the collection of data, the generation of knowledge, and the provision of policy advice. Yet while the act of delegation includes a promise to defer to an organisation in the future, for instance by acting upon its recommendations and requests, addressees may eventually not do so.Footnote 6 Whereas the competencies associated with de jure expert authority are not necessarily always recognised and deferred to in practice, in the case of ‘de facto authority’, they are.

This discrepancy has largely not been addressed in the research because many scholars have focused on inter-IO comparisons and on the global influence of international bureaucracies.Footnote 7 However, case study research – for instance, studies on the expert authority of specific international bureaucracies,Footnote 8 treaty secretariats,Footnote 9 and peer review mechanisms in IOsFootnote 10 – has produced a more nuanced picture of the ways in which expert authority can increase or decrease due to the elements inherent in the relationship between international bureaucracies and their addressees. This research has found that authority depends on the ‘specific social settings’,Footnote 11 that it ‘is not a fixed quality any actor may possess’,Footnote 12 ‘does not spring magically from some ideal-typical “source” of authority’,Footnote 13 and that it may vary, not only among international bureaucracies and over time, but also between the international bureaucracy and its various subordinates. Furthermore, these previous assessments and explanations of authority have shown that authority, while likely delegated, draws on other sources as well, including perceptions of international bureaucracies as impactful and objective.Footnote 14 By providing a systematic analysis of large-N variations in the expert authority ascribed to international bureaucracies by a key audience, we add to these debates.

In addition, our analysis contributes to the burgeoning literature on the power of international bureaucracies.Footnote 15 This literature has increasingly focused on the structural conditions under which international bureaucracies become influential. For instance, regime complexity creates a demand for overlap management and offers a vacant slot in global governance that international bureaucracies fill.Footnote 16 Technical and scientific uncertainty increase state demand for international bureaucracies’ expertise, while low issue salience increases the autonomy of international bureaucrats,Footnote 17 another important source of international bureaucracies’ influence.Footnote 18 Much of this research has focused on international bureaucracies’ influence at the global level, for instance, their influence on the institutional design of newly created IOsFootnote 19 or on the incorporation of new issues into regimes.Footnote 20 We add to this research by, inter alia, shifting the focus from their role as ‘managers of global change’Footnote 21 to their role on the national level.

We used novel data from a global survey of policy units in national ministries in 121 countries to assess the scope and variation of de facto expert authority. This survey captures the extent to which international bureaucracies possess de facto expert authority among this important group of addressees. We selected nine international bureaucracies as potential authority holders and asked the policy officials to what extent they recognised these bureaucracies’ expert authority in eight thematic areas: four in the policy field of agriculture and four in the policy field of finance. The sample is representative of all UN regions and all World Bank income groups. We achieved a response rate of 38 per cent. Our data reveal that de facto expert authority varies not only across international bureaucracies but also across thematic areas and addressees.

To explain the variation in de facto expert authority, we tested the most prominent assumptions in the literature about the sources of de facto expert authority. Specifically, we focused on perceptions of international bureaucracies to better understand how the relationship between an international bureaucracy and its addressees systematically shapes the expert authority the international bureaucracy holds over them. We examined the role of international bureaucracies’ impartiality, objectivity, and impact, as perceived by their national addressees. We also studied the role of knowledge asymmetries between national addressees and international bureaucracies, as these make it more likely that addressees will recognise them as experts and defer to their authority. In doing so, we compare these factors with alternative sources of influence, such as coercion, third-party pressure, and national interest.

Four findings stand out. First, the perception of international bureaucracies’ global impact, that is, their perceived contribution to effectively addressing global challenges, has the greatest effect on their de facto expert authority. Second, we find that perceptions of objectivity play the smallest role of all the determinants considered. Third, we find that varying impartiality perceptions are not associated with varying degrees of expert authority. This partially challenges well-established arguments in some strands of the literature on expert authority, where objectivity and impartiality are seen as central. Finally, we find some indications that knowledge asymmetries might play a role in expert authority.

The article begins by conceptualising de facto expert authority and briefly mapping its variation. A description of our data shows the variation that we seek to explain. Second, we specify established assumptions under which de facto expert authority becomes likely. Third, we describe the methods and models we use, before turning, fourth, to a series of tests and analyses. Finally, we outline implications for the further study of international authority and the influence of international bureaucracies.

International bureaucracies’ expert authority

Our article focuses on the concept of de facto expert authority. In the following, we briefly discuss key characteristics of expert authority before elaborating on the specific form of de facto authority. Then we turn to the variation in the expert authority international bureaucracies hold over national addressees.

What is expert authority?

Expert authority (or epistemic authority) is a specific type of authority. It denotes the recognition of experts’ competency to make (and communicate) assessments, judgements, and recommendations based on their knowledge,Footnote 22 which enables them to ‘structure the behavior of others’.Footnote 23 While expert authority can be distinguished from other types of authority, such as political authority,Footnote 24 it shares the essential characteristics of a broader and more general concept of authority. In recent years, the concept has proven to be useful for theorising hierarchical relationships among various actors that participate in global governance.Footnote 25 It is generally defined as a social relationship and a distinct form of power. First, authority rests on a social and hierarchical relationship between at least two actors. In this relationship, the superior actor claims or exercises authority by ordering or requesting certain actions, while the subordinate actor recognises this privilege and voluntarily defers to the respective commands or requests, that is, does what an authority holder asks.Footnote 26 The relationship is, thus, recognised and entails deference. Second, authority is regarded as a distinct form of power.Footnote 27 Following Hannah Arendt,Footnote 28 many scholars distinguish authority from other modes of social control, notably from ‘both coercion by force and persuasion by arguments’, which relate to other motives for deference.Footnote 29 In the case of authority, deference should be based on trust in certain qualities of the actor that claims authority, for example, credibility.Footnote 30

Recognition is key to the concept of authority in general as well as to its specific variants. Authority is recognised in two key ways. On the one hand, subordinate actors may place an actor ‘in authority’Footnote 31 by approving rules that formally establish their subordination and by delegating tasks and powers to the authority holder. This variant is often called ‘delegated authority’Footnote 32 or ‘de jure authority’.Footnote 33 It is typically preceded by an act of delegation and entails a promise to defer in the future. On the other hand, subordinate actors may make an actor ‘an authority’Footnote 34 by recognising it through their behaviour, also referred to as ‘de facto authority’.Footnote 35 In this variant, authority can be ascribed irrespective of a formal act of authorisation. Subordinate actors then recognise a superior actor's privilege to request certain actions and do or at least consider doing what they are asked to do. Existing research on international authority has been strongly shaped by this distinction and the related means of measuring authority. Thus, the different forms of recognition also matter empirically. De jure authority of IOs has increased over time and varies widely among IOs. For example, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) has relatively low de jure authority, while the International Monetary Fund (IMF) scores relatively high.Footnote 36 Yet, given that delegation means that a collective principal (a group of member states) conditionally grants authority to an agent (an IO or international bureaucracy), the mere act of delegation cannot tell us much about the varying degrees to which subordinates adhere to this decision and defer to the agent in practice.

Hence, we apply a concept of de facto expert authority. In doing so, we adhere to the view, outlined above, that authority is a social, not merely a contractual, relationship. This relationship is built on behavioural recognition and includes deference. We, therefore, examine whether a key audience considers international bureaucracies’ policy recommendations because they regard them as experts.

Variation in de facto expert authority

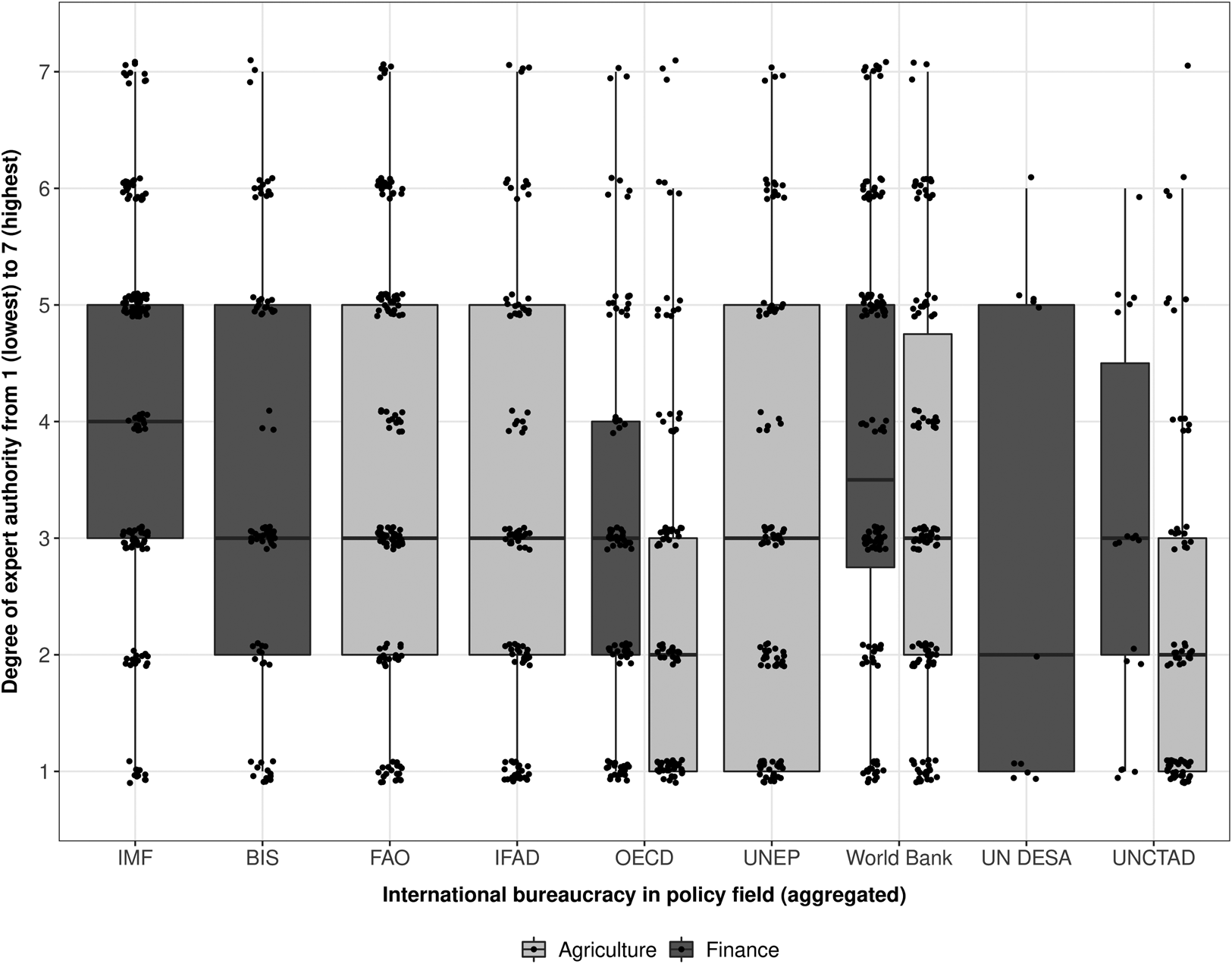

Our data, which we describe below, show that the extent to which international bureaucracies hold de facto expert authority varies considerably across ministry officials, international bureaucracies, policy fields, and thematic areas. Figure 1 displays how responses of ministry officials are distributed across the response categories in a survey question on de facto expert authority of a sample of nine international bureaucracies (on an ascending scale from 1 to 7).

Figure 1. Absolute frequency of responses regarding the degree of expert authority.

Source: Our survey (see research design below).

Figure 2 further highlights that expert authority varies across the actors recognising and deferring to the authority (see values) and across policy fields (see variations in shading of the boxes). We also find variation across thematic areas in the same policy field. For example, the IMF, OECD, and World Bank all have less expert authority in monetary policy than in other thematic areas (see Figures A1, Appendix A; A2, Appendix C in the supplementary material). Three observations stand out. First, and not surprisingly, international bureaucracies vary in the level of expert authority ascribed to them: The IMF has, on average, the highest expert authority. Second, de facto authority varies across policy fields as domains of authority. In the policy field of agriculture, the variation among international bureaucracies is less pronounced than in finance. Looking at the OECD and World Bank individually, we observe that each international bureaucracy shows wide variation in expert authority across policy fields. Third, there is wide variation in the expert authority of the same international bureaucracy across ministry officials (as shown by the dots in Figure 2). Except for UNCTAD (in financial policy) and UN DESA, ministry officials’ responses are spread among all possible response categories.

Figure 2. Expert authority: Boxplot by international bureaucracy.

Source: Our survey (see research design below). Data are grouped by international bureaucracy in the policy fields of agriculture and finance, respectively, and ordered according to an international bureaucracy's overall median level of expert authority.

Our data on international bureaucracies’ de facto expert authority confirms that authority appears ‘in gradations’Footnote 37 and that the same bureaucracy may have authority in one setting but not in another. This variation corroborates the importance of studying authority as a social relationship between international bureaucracies as authority holders and their addressees as potential authority followers (here: policy units in national ministries). It is this relationship that we seek to explain.

Explaining the variation in de facto expert authority: Theories and hypotheses

While de jure authority is usually explained with reference to functionalist or rationalist-institutionalist theories, de facto expert authority is often explained with reference to sources of authority within the international bureaucracy. The latter may be a result of the delegation of authority that occurs in the case of de jure authority, but the literature typically assumes that de facto authority rests on alternative attributes, such as expertise.Footnote 38 Still, not every international bureaucracy has these attributes or is recognised as having these attributes. Ole Jacob Sending, for example, argues that ‘authority – as a relational phenomenon – cannot be determined by looking at the attributes of one actor’.Footnote 39 And Michael Barnett and Martha Finnemore also emphasise that international bureaucracies ‘must be seen to serve some valued and legitimate social purpose, and, further they must be seen to serve that purpose in an impartial and technocratic way’ in order to become or stay ‘authoritative, ergo powerful’.Footnote 40 While many scholars acknowledge the relational character of authority, only few have examined how a key audience perceives what could count as a source of authority.Footnote 41

Therefore, our explanations pay heed to the addressees of international bureaucracies’ expert advice and are sensitive to their perceptions, assessments, and demands. In the following, we introduce the most established assumptions on the different sources of de facto expert authority and indicate how we operationalise them to bring in the views of those who are asked to recognise and defer to the expert authority of international bureaucracies.

Perceived neutrality

First, it is often assumed that expert authority relies on the appearance of an expert as neutral.Footnote 42 A recent review of research findings on international bureaucracies states that ‘[i]n general, scholars have found the influence of international bureaucracies to be strongest when their expertise was perceived as being objective, impartial, fair or valid.’Footnote 43 This hypothesis goes back to Max Weber, who wrote that bureaucrats act in a professional (impersonal) capacity, indicating that they are acting on others’ behalf instead of their own.Footnote 44 The underlying causal mechanism rests on credibility. Information and advice are deemed less credible when they appear to be biased, and bureaucrats are only deemed trustworthy when they appear to be neutrally fulfilling their tasks.Footnote 45 Perceived neutrality is thus regarded as a major source of expert authority.

Neutrality can refer to two different concepts: impartiality and objectivity.Footnote 46 Each of them has been linked to expert authorityFootnote 47 and our article, therefore, addresses both. Impartiality is typically understood as setting one's own interests aside and treating all actors equally.Footnote 48 An impartial bureaucracy is one that generates information and disseminates policy recommendations that appear to be unpartisan and thus unaligned with specific governments’ preferences.Footnote 49 Since the League of Nations, international bureaucracies have been designed to represent the opinions of all nations without favouring ‘more narrowly defined national interests’.Footnote 50 It is assumed that impartiality signals an international bureaucracy's (or another IO body's) independence and generates credibility, thereby increasing the agency and influence of the latter.Footnote 51 Objectivity is understood as scientific rationality. An objective bureaucracy is one that generates and disseminates information and policy recommendations that appear efficient, impersonal, and embodied in abstract rules and, hence, not as serving specific ideologies.Footnote 52 It is assumed that perceived objectivity and authority are connected because politicisation and ideological bias undermine the credibility of an expert.Footnote 53 Scholars argue that international bureaucracies are aware of this, and therefore spend considerable time on presenting their policy advice in objective and evidence-based ways, for instance, by quantifying information.

However, more recent literature has demonstrated that neutrality is more of a claim, a contested and changing norm, or even a myth than it is an inherent feature of international bureaucracies.Footnote 54 Instead, it might vary and therefore might also account for variations in expert authority. To begin with, it would be naïve to assume that all international bureaucracies manage to present themselves as promoters of impartial and objective knowledge and advice. Several studies have found that organisational outputs are not free from interference by member states.Footnote 55 They are also informed by ideologies, normative orientations, and organisational cultures.Footnote 56 What follows from this is that international bureaucracies may sometimes fail to produce entirely impartial and objective advice. Furthermore, we assume that some bureaucracies are more successful than others in creating and upholding an appearance of neutrality, which is ultimately what counts.

Moreover, we assume that different states hold different views of bureaucracies’ impartiality and objectivity. Varying perceptions of impartiality may reflect biases that occur due to interest heterogeneity and power asymmetries. States have different interests, and their ability to steer the policies of international bureaucracies into line with their preferences varies tremendously. They hold different positions of power in intergovernmental decision-making and are represented to different degrees within international bureaucracies.Footnote 57 As a consequence, the less represented states will be unlikely to perceive the bureaucracy as impartial.Footnote 58 Varying perceptions of objectivity may reflect the tendency to privilege certain values and ideologies. Stephen C. Nelson, for instance, has argued that ideational like-mindedness between IMF staff and domestic policymakers influences IMF staff decisions.Footnote 59 We presume that such biases call a bureaucracy's objectivity into question, at least from the viewpoint of those states that hold a different ideational position.

Our survey indeed confirms that policy units of national ministries have very different perceptions of the impartiality and objectivity of international bureaucracies’ work. A given international bureaucracy is often perceived quite differently by ministry officials from different countries, and there is similar variation across thematic areas. Figure A.4 in Appendix E (supplementary material) also shows that, in the case of impartiality, this variation cannot be sufficiently explained by formal rules that grant international bureaucracies formal independence. Hence, we argue that we have to consider stakeholders’ perceptions of international bureaucracies’ impartiality and objectivity when seeking to explain international bureaucracies’ de facto expert authority.

Based on these explanations, we derive the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1a. The more impartial the work of an international bureaucracy is perceived to be, the higher the international bureaucracy's de facto expert authority.

Hypothesis 1b. The more objective the work of an international bureaucracy is perceived to be, the higher the international bureaucracy's de facto expert authority.

Perceived impact

A second explanation for international bureaucracies’ de facto expert authority is their perceived contribution to effectively addressing global challenges, which we call perceived impact. The underlying causal mechanism rests on the expectation that international bureaucracies help to solve policy problems. Thus, expected benefits are the main reason for the addressees of an international bureaucracy's advice to grant authority to the actor in the first place.Footnote 60 Once an authority relationship is established, it continues to rest on the ability of the actor to serve ‘some valued and legitimate social purpose’.Footnote 61 Accordingly, international bureaucracies’ expert authority is called into question when they are perceived to perform badly.Footnote 62 We find the same expectation for national bureaucracies in the public administration and management literature.Footnote 63 Hence, we assume that ministry officials who have to propose solutions to specific policy problems turn to those international bureaucracies whose performance they value.

When evaluating IO performance or regime effectiveness, the literature generally focuses on outputs, outcomes, or impacts.Footnote 64 We focus on perceptions of impact. While outputs comprise various activities of international bureaucracies such as publications or policy programs, outcomes refer to the desired behavioural changes induced by these outputs, for instance, the implementation of international bureaucracies’ policy recommendations by states. Impacts refer to the extent to which organisational outputs eventually bring about a solution to the underlying problem in the broader socioeconomic or ecological environment. Impact is often also referred to as problem-solving effectiveness.Footnote 65

We opt to focus on the impact dimension since the ultimate goal of global governance and IOs’ mandate is to address global challenges. IOs are created to ‘help guide states through the challenging maze posed by the current international agenda by developing effective road maps’.Footnote 66 Furthermore, we consider measures that focus on the output and outcome dimensions to be unsuitable indicators for our purposes because they conceptually overlap with our dependent variable. Policy advice is an organisational output, while its consideration by national bureaucrats is a potential outcome. Thus, any evaluation of these two would likely intersect with the concept of expert authority and could lead to problems of endogeneity.

International bureaucracies’ perceived impact is less prone to these problems. This holds particularly for impact at the global level, which is our focus here. It appears conceivable that more authority contributes to a higher impact at the national level. Yet far more conditions would have to be met for de facto expert authority to have a greater impact at the global level. First, policy units, as the addressees of expert authority, would have to comply and implement the international bureaucracies’ policy advice. The mere consideration of international bureaucracies’ advice – our measure for deference to authority – does not necessarily result in compliance. Obviously, while ministry officials are important gatekeepers, they can neither order nor decide alone on the implementation of policies. Second, even when advice is acted upon, this may have no effect on international bureaucracies’ global impacts, in the sense of their ability to effectively address a given global problem. A frequently cited explanation for this lack is unambitious policy goals.

By contrast, there is a much more direct relationship between international bureaucracies’ perceived global impact and their de facto expert authority over policy units in national ministries, and the demands that must be met for this relationship to unfold are much lower. Policy units only need to be familiar with the international bureaucracy and to have formed an assessment of its global impact. Therefore, we study the relationship between the perceptions of international bureaucracies’ global impact and their de facto expert authority among national policy units.

We thus hypothesise:

Hypothesis 2. The higher an international bureaucracy's global impact is perceived to be, the higher its de facto expert authority.

Potential knowledge asymmetries

A third explanation for expert authority refers to knowledge asymmetries that are caused by factors such as a lack of and demand for cognitive resources. The idea of specific (and, thus, rare) expertise as an important source of power features prominently in the public administration literature and in theories of delegation.Footnote 67 This idea can be traced back to the Weberian paradigm of bureaucratic influence, in which information asymmetries are seen as central for bureaucracies’ influence because bureaucrats possess specialised knowledge and skills that elected officials lack.Footnote 68 The literature on the potential power of IOs and international bureaucracies seems to presume that international bureaucracies possess a ‘comparative informational advantage’Footnote 69 in terms of specialised knowledge, training, and experience vis-à-vis stakeholders.Footnote 70 Yet, such knowledge asymmetries should not be taken for granted since governments vary in terms of their own cognitive resources.Footnote 71 Since all international bureaucracies in our sample provide policy advice, we opt to study the asymmetry from the perspective of the state ‘demanding’ the expertise, and not the perspective of the bureaucracy ‘supplying’ the expertise.

Following from the above considerations, one may expect international bureaucracies to enjoy more expert authority in states that lack cognitive resources or expertise within their government ministries and therefore have a higher demand for external information and advice. These are usually states with comparatively low state budgets, whose ministries are less well equipped in terms of human and financial resources. Low state budgets also impair the production of knowledge within the country. They influence the number of staff and experts in the ministries, and the ‘possibilities for states to buy in external expertise’.Footnote 72 For example, IMF staff members report that most developing economies lack a tax policy unit ‘tasked to guide and inform the tax policy debate, based on facts, independent data analysis, and multidisciplinary efforts’.Footnote 73 Governments that lack resources, including expertise, often turn to international bureaucracies for assistance.Footnote 74 Not only do many international bureaucracies offer advice; in contrast to private actors, they usually provide it free of charge.

Finally, it is plausible that knowledge asymmetries render it more difficult for ministries to validate other actors’ advice. They are therefore more likely to accept policy advice independent of an examination of its content and mainly because it comes from a specific source. Consequently, we expect that countries with more limited resources are more likely to ascribe expert authority to an international bureaucracy.

Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3. The higher the potential knowledge asymmetry to the advantage of the international bureaucracy, the higher the international bureaucracy's de facto expert authority.

Research design

We used a cross-sectional survey among ministries in a representative sample of 121 countries to collect the data. The choice of this data collection method was mainly motivated by the conceptualisation of de facto expert authority in the literature and the related implications for its operationalisation and measurement. First, given that the ‘problem of observational equivalence between authority and other forms of social control runs deep’,Footnote 75 any measurement of de facto expert authority must be distinguishable from other forms of power, such as coercion, incentives, and content-dependent persuasion. Second, any measurement of de facto expert authority must be suitable to grasp its relational character. Third, de facto expert authority must not be equated with the communication of knowledge-based policy advice or the mere possession of knowledge by the international bureaucracy. Experts must be recognised as such by their audiences. Such recognition may rest either on observable attributions or on the mere assumption that a superior actor has specialised and reliable knowledge.Footnote 76 Fourth, authority should not only be derived from its effects. It would be insufficient to conclude that every observed instance of compliance with international bureaucracies’ recommendations stems from authority without studying whether compliance is related to the prior recognition of these bureaucracies as experts.Footnote 77 Fifth, deference to authority does not mean that actors have to comply with the requests of a superior actor; it suffices when they are ‘carefully listening to what they say’.Footnote 78 Hence, it is not necessary that they eventually adopt and implement the policies, but only that they consider what international bureaucracies recommend.Footnote 79

Survey questions can be asked in a way that allows us to distinguish expert authority from other forms of power, for instance, coercion and related concepts, such as expertise. This helps to avoid the problem of observational equivalence. Moreover, three of our main hypotheses (impartiality, objectivity, and impact) are based on perceptions, which can also be captured by a survey.

Selection of international bureaucracies and respondents

The survey comprises nine global bureaucracies in four thematic areas of agricultural policy and four thematic areas of financial policy.Footnote 80 The international bureaucracies were selected in a process consisting of multiple and interrelated steps. To enable comparison, we preselected a list of international bureaucracies and thematic areas. If we had not done so, survey respondents might have only assessed the work of the international bureaucracy they knew best or disliked most, and the bureaucracies would have differed from respondent to respondent. To ensure comparability, we selected broad policy fields and specific thematic areas in which several international bureaucracies with global reach were active. For our analysis, it was important that these international bureaucracies themselves claimed to have authority in a particular policy field and thus qualified as candidates for expert authority: it would have made little sense to examine the conditions under which, for instance, the World Tourism Organization is recognised as an expert authority in debt management policy. Therefore, in the preselection process, we verified that each international bureaucracy in our sample had communicated policy advice by studying websites, documents, and flagship publications. We chose only those bureaucracies that generally address their advice to all states worldwide, and we only selected thematic areas that were specific enough that we could match them with policy units in national ministries as potential addressees of policy advice.Footnote 81 Our final selection met these criteria best.

In order to assess international bureaucracies’ de facto expert authority, the survey targeted the policy units in national ministries that work in the aforementioned thematic areas. We sent an invitation to participate in the survey to those officials chiefly responsible for the thematic areas in their country. Most of these officials held a position as head of the respective policy unit in their ministry. We chose this group of respondents for several reasons. First, ministry officials are among the most important addressees and recipients of international bureaucracies’ policy advice. Additionally, they play a key role as ‘gate-keepers of policy research and analysis’ at the national level, where they brief government officials.Footnote 82 They can thus be regarded as important interlocutors and policymakers. Second, we were interested in the prevalent practices of policy units in national ministries rather than individual, personal assessments. The heads of policy units can best provide information on the practices of their units. Therefore, the questionnaire explicitly requested that respondents indicate the prevalent practices in their respective units.Footnote 83 We consider our respondents to be highly qualified to make these assessments given their long-standing work experience. Almost half of the respondents had more than ten years of work experience in the respective thematic area and had been working in the ministry for at least five years. Only 3 per cent of the respondents had less than one year of thematic work experience. Furthermore, we found no pattern between the respondents’ level of seniority and international bureaucracies’ expert authority.

The invitations to participate in the survey were personally addressed to the heads of the respective ministry unit, and most were sent out by mail.Footnote 84 The invitations also included a paper questionnaire that could be sent back by mail, fax, or email, but most respondents used the online questionnaire. The questionnaire was available in English, French, German, and Spanish. By using this approach, we achieved an extraordinarily high response rate of 38 per cent, which corresponds to 362 received questionnaires and 1,785 individual observations for the nine international bureaucracies (see also Appendix C in the supplementary material for further details on the response rate).

Overall, our survey sample included policy units in ministries in 121 countries. The countries were selected using a stratified sampling process, whereby the survey population (all UN member states) was stratified according to the UN region and World Bank income classification (see Appendix A in the supplementary material for further details).

Survey design

Our survey uses a single-source, self-report, cross-sectional research design. It provides information on the dependent variable and three of the independent variables, which may result in a spurious covariance between independent and dependent variables.Footnote 85 The risk of so-called common method variance (CMV) or common method bias can best be avoided when measures are collected from different sources or when the predictor and the criterion, that is, the independent and the dependent variables, are measured separately. Yet, given that this was a global survey of high-ranking ministry officials who have limited time available, it was not feasible to split groups (that is, ask two officials within the same unit) or to split the questionnaire and ask respondents to answer the separate parts at different points in time.

To assess the risk of CMV, we conducted a Harman's single-factor test based on the survey data collected. The test gives no indication that CMV is an issue. However, since this test has some limitations, we took several precautions in the design stage to avoid the four main causes of CMV,Footnote 86 as recommended in the literature.Footnote 87

First, regarding common rater effects, we implemented procedural remedies for social desirability bias, leniency, and acquiescence by assuring respondent anonymity and detailing our high standards of privacy and data protection.Footnote 88 We also selected respondents with high expertise to answer our survey questions. Survey research has found that accurate answers depend on matching ‘the difficulty of the task of answering the question with the capability of the respondent’ and on motivating respondents to participate by providing clear instructions and stressing how important their unique perspectives are.Footnote 89 Second, we sought to reduce item ambiguity and related comprehension problems by formulating the questions as concisely as possible (see below). Respondents were also offered various opportunities to clarify any comprehension questions throughout the process of participation.Footnote 90 We further used different response scale anchors for different constructs to avoid automatic response consistency.Footnote 91 Third, we controlled for measurement context effects by carrying out a self-administered survey. We chose computer-administered questionnaires or paper-and-pencil questionnaires instead of verbal or face-to-face interviews to avoid the problem of respondents giving biased answers due to the presence of an interviewer.Footnote 92

While we employed a range of remedies for item context effects, some additional remedies were not used due to lower feasibility in expert surveys. For instance, we opted against counterbalancing or randomising question order because this would have made it impossible to progress from general to specific (and more sensitive) questions, an approach that is recommended in the survey literature. It would also have required the use of survey software, which was again not feasible given that the majority of ministry officials targeted in our survey had to be contacted by mail, and many respondents from the Global South preferred paper-and-pencil questionnaires.Footnote 93

Finally, we followed the advice in the survey literature to employ single-item measures for our constructs. While multi-item constructs are preferable under certain circumstances,Footnote 94 they typically require established valid measures, and bear the risks of sampling bias and consistency motifs: a lengthy survey may overload or bore respondents, thus reducing response rates and accuracy.Footnote 95 Single measures have the advantage of being more parsimonious and less time-consuming, but also require that each measure captures the construct as precisely as possible. We followed the suggestion in the literature to ask experts to select the item that most closely captures the construct of interest.Footnote 96 We developed the survey questions with feedback from a range of political scientists and public officials at the subnational level before pretesting the survey questions with officials from several world regions working at ministries other than those included in our survey.

Dependent variable

To capture our dependent variable – expert authority as a social relationship between authority holder and subordinate actor – we constructed the survey question to include both the recognition of international bureaucracies as experts and the deference to their advice. We directly asked national ministry officials – as the addressees of international bureaucracies’ policy advice – whether, and to what extent, they had considered an international bureaucracy's advice in the work of their unit (action) because they regard the international bureaucracy to be an expert in the given thematic field (attribution).Footnote 97 The seven response categories for this question refer to seven different degrees of EXPERT AUTHORITY (from high to no expert authority).

Our question leads to a rather strict measure. The concept of authority is source-specific. This means that a given entity holds authority without any need for persuasion, and that the addressees of its policy advice generally consider that advice without a thorough examination of its content. We therefore asked if ministry officials follow the policy advice because they regard the international bureaucracy as an expert whose advice does not require further examination. We chose a wording that helped us to exclude other forms of power, such as conditionality, enforcement, and pressure, which could also play a role in the consideration of policy advice. These other forms of power were, however, the subject of separate questions and form part of our robustness checks.

Independent variables

Data on the perceived impartiality, objectivity, and impact of an international bureaucracy were also collected by means of separate survey questions. IMPARTIALITY (hypothesis 1a) is operationalised as the extent to which the bureaucracy is perceived as not representing some countries’ interests more than others. OBJECTIVITY (hypothesis 1b) is operationalised as the degree to which the bureaucracy is perceived as not being biased in favour of certain values or ideologies. The IMPACT of an international bureaucracy (hypothesis 2) is operationalised as its perceived contribution to effectively addressing current challenges at the global level. Figure 3 shows the absolute frequencies of the three survey-based independent variables.

Figure 3. Absolute frequencies of the survey-based independent variables.Footnote 98

Data on the knowledge asymmetry hypothesis (hypothesis 3) were not collected through the survey, since self-reports on the cognitive resources of survey respondents (or the ministry they work for) and their self-perception as experts would have been highly prone to the influence of both social desirability and leniency bias. Instead, we measured ASYMMETRY by the inverse of the country's gross domestic product (GDP) and taking the natural log of this ratio.Footnote 99 In related studies, this indicator is a well-established proxy for measuring the degree to which a country lacks cognitive resources and therefore lacks alternatives to external expertise and advice. The indicator is assumed to reflect the human resources within a ministry as well as the financial resources available to ministry staff to develop their expertise.Footnote 100 Due to limited data availability and quality, we opted for this indicator instead of other conceivable indicators, such as gross domestic expenditure on research and experimental development (GERD) from the UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS) databaseFootnote 101 or bibliometric indicators, for example, from the SCImago Journal & Country Rank database.Footnote 102 Nevertheless, we checked the validity of our indicator and found that the GERD indicators and the bibliometric indicators highly correlate with GDP (average Pearson's r at 0.85, see Appendix F in the supplementary material).

Control variables, fixed effects, and clustered standard errors

We include a range of control variables in our regression models to test the robustness of our results and to correct for a possible omitted variable bias.

First, we test whether the correlations of IMPARTIALITY, OBJECTIVITY, IMPACT, and ASYMMETRY with EXPERT AUTHORITY hold when other motives to consider an international bureaucracy's policy advice are also present and coincide. To this end, we control for: (i) the congruence of the bureaucracy's policy advice with the policy preferences of the official's country (CONGRUENCE); (ii) the IO's overall potential to induce deference by means of conditionality and/or enforcement (COERCION);Footnote 103 and (iii) potential third-party pressure to act on the advice from a specific international bureaucracy (PRESSURE).Footnote 104 We acknowledge that deference to an international bureaucracy's advice might be driven by other instruments of an IO (coercion), the orchestration of third parties (pressure), or the tailoring of advice to domestic policy preferences (congruence). For example, the IMF and the World Bank, which are included in our sample, are known for their conditionality, while the OECD is known for orchestrating peer pressure.

Second, to account for heterogeneity across countries, we include variables at the country level. These comprise countries’ level of development, measured by their GDP per capita (log),Footnote 105 countries’ political rights and civil liberties based on Freedom House data,Footnote 106 countries’ level of corruption (CORRUPTION (WGI)Footnote 107 and CORRUPTION (TI),Footnote 108 and the importance of the respective thematic area on the government's policy agenda as indicated by respondents in the survey (IMPORTANCE).Footnote 109

Third, we include fixed effects for each international bureaucracy in each thematic area in all models. Given that institutional design variables and particularities of the policy field play a minor role in the theoretical debate on de facto expert authority, we lack testable assumptions as to how they affect the outcome of interest, that is, the expert authority relationship between a national ministerial unit and an international bureaucracy. Fixed effects take into account that international bureaucracies are likely to differ in institutional design, financial and human resources, and activities in the different thematic areas.Footnote 110 As described above, our data reveal variation in expert authority across international bureaucracies in thematic areas (see Figures A1 in Appendix B and A2 in Appendix D in the supplementary material).

Fourth, we use clustered standard errors on the respondent level in all models to correct for heteroscedasticity due to respondent-specific influences. We do so for two reasons. First, in our questionnaire, each respondent evaluated several international bureaucracies, and thus, the evaluations may not be independent. For example, the respondent might hold a certain view about multilateral institutions in general. Second, research on public attitudes towards IOs has shown that survey respondents use heuristics based on their experiences with more familiar national institutions when assessing IOs with which they might be less familiar.Footnote 111 We assume that our survey participants (ministry officials working in the same thematic areas as the international bureaucracies that we asked about) are much more familiar with IOs than survey participants in the research on public attitudes to IOs (citizens or societal actors). Nevertheless, we aimed at minimising the possibility that respondents used national heuristics and designed our survey questions accordingly. Not only did we offer the answer category ‘advice or work not known’; we also avoided questions involving abstract concepts, such as authority or neutrality. Instead, our questions were worded specifically to encourage respondents to think of particular qualities of international bureaucracies or their own personal interactions with them.

Results

To explain international bureaucracies’ de facto expert authority, we ran several ordinary least square (OLS) regressions. First, we present the estimates of a model focusing only on the four main explanatory variables discussed above: IMPARTIALITY, OBJECTIVITY, IMPACT, and ASYMMETRY (Model 1). In a second step, we include the three control variables: CONGRUENCE, COERCION, and PRESSURE. Table 1 displays the regression results for Model 1 and 2, and Figure 4 illustrates the standardised coefficients and 95 per cent confidence bands based on the estimations of both models.

Figure 4. Regression coefficient plots of Models 1 and 2.

Notes: Dots represent standardised effect sizes of each explanatory variable with 95 per cent confidence intervals as estimated from Models 1 and 2 and indicate the direction and magnitude of the effect of each variable on expert authority. The coefficients are indistinguishable from zero (p < 0.05) when the bars cross the zero line.

Table 1. Explanatory models for expert authority.

Notes: OLS regressions with two-tailed significance for estimates. ’p < 0.1; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001. Standardised coefficients with robust standard errors clustered by respondent (in parentheses). Fixed effects for the international bureaucracies in their thematic areas are omitted from the table.

Overall, there is considerable support for the importance of explanations based on the perceived impact and objectivity of international bureaucracies and the knowledge asymmetry in favour of the international bureaucracy, but the correlations are not equally strong. International bureaucracies’ IMPACT is by far the strongest determinant of EXPERT AUTHORITY, with highly significant and positive coefficients in both models, although the coefficient decreases from 0.534 (Model 1) to 0.360 when including the control variables (Model 2). Thus, the higher the perceived global impact, the greater the international bureaucracies’ expert authority among policy units in national ministries, all else equal. The coefficients for OBJECTIVITY are also positive and statistically significant in both models. Here, the coefficient increases slightly from 0.115 (Model 1) to 0.144 (Model 2). Hence, the less an international bureaucracy's work is perceived to be biased towards particular values and ideologies, the greater its expert authority. Knowledge asymmetries also influence international bureaucracies’ expert authority: the more limited a state's cognitive resources, the more expert authority international bureaucracies enjoy among ministry officials from these countries. These results are robust to a variety of specification choices (see below).

However, we can reject the hypothesis that the perceived impartiality of international bureaucracies’ work enhances their expert authority. The coefficients for IMPARTIALITY are negative in both models, which already contradicts our expectation of a positive relationship with EXPERT AUTHORITY. Moreover, the correlation is small and statistically insignificant. Hence, impartiality is not associated with expert authority. This does not only contradict our expectations but also challenges a prominent assumption in the literature on the relationship between expert authority and impartiality.Footnote 112 What could explain our finding of almost no correlation between impartiality and expert authority? A methodological explanation might be that IMPACT absorbs the effects of IMPARTIALITY, since the latter might contribute to an international bureaucracy's perceived impact. To account for this possibility, we estimated the model excluding each of the two variables. In both variants, the results remain robust and IMPARTIALITY continues to have no statistically significant effect. A theoretical explanation might be that impartiality only matters for de facto expert authority under certain circumstances. In this case, impartiality would have no significant effect on expert authority in the overall sample. For example, it is conceivable that ministry officials care less about impartiality when the international bureaucracy's advice is congruent with national policy preferences, and that they happily recognise the expert authority and defer to it.Footnote 113 In the reverse case, that is, when the advice is not congruent, or is less congruent with national policy preferences, impartiality may be more important for expert authority. Here, ministry officials might have to justify why they intend to follow advice that runs counter to or does not fit their national policy preferences and to do so, they might look at the impartiality of a bureaucracy's work. However, as we elaborate below, our additional analyses reveal that impartiality is never correlated with expert authority, irrespective of the degree of policy congruence.

The regression results in Model 2 also show that the coefficients of the two control variables PRESSURE and CONGRUENCE are positive and statistically significant at the 5 per cent level. The coefficient of the variable CONGRUENCE is even the second largest in Model 2. Furthermore, the coefficient of the variable COERCION is also statistically significant but only at the 10 per cent level and the size of the coefficient is comparatively small.

At first sight, and given the lack of theoretical arguments in the literature that coercion and congruence cause expert authority, these observations only confirm our expectation that the expert authority of international bureaucracies might empirically coincide with other means that they rely on to have their voice heard. In other words, it occurs quite often that ministry officials perceive an international bureaucracy to be an expert authority, and therefore, consider its policy advice, while they also find its advice to be highly congruent with the policy preferences in their country, perceive the respective IO to have coercive potential, or feel pressured by other actors to follow its advice. To be sure that de facto authority occurs in the absence of other forms of power and other motives for the consideration of policy advice, we performed several additional tests. First, descriptive statistics show that higher levels of expert authority are even attributed to international bureaucracies when they belong to IOs that are perceived to have low coercive potential (see Figure 5 below. For the respective figures for the degrees of expert authority conditional on PRESSURE and CONGRUENCE, see Appendix G in the supplementary material).

Figure 5. Comparison of the frequency of responses for different degrees of expert authority conditional on the perceived coercive potential (IOs with low versus IOs with high perceived coercive potential).

To assess in greater detail whether our explanations for EXPERT AUTHORITY change when other motives to consider international bureaucracies’ policy advice are present or not (and given that the regression results in Models 1 and 2 slightly differ), we decided to create respective subsamples and contrast the two extremes of each of these control variables (lower versus higher values).Footnote 114

Models 3 and 4 distinguish IOs with lower coercive potential from IOs with higher coercive potential (as perceived by the policy units in national ministries). Models 5 and 6 differentiate between international bureaucracies whose advice is perceived to be rather incongruent with national preferences and those whose advice is perceived to be rather congruent. Models 7 and 8 separate the sample according to whether policy units in national ministries felt pressured to a high or to a low extent by other actors to act on an international bureaucracy's advice. Table 2 presents the results of these estimations.

Table 2. Results of Models 3 to 8 (subsamples).

Notes: OLS regressions with two-tailed significance for estimates. ’p < 0.1; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001. Standardised coefficients with robust standard errors clustered by respondent (in parentheses). Fixed effects for the international bureaucracies in their thematic areas are omitted from the table.

Most importantly and remarkably, the results on our variables IMPARTIALITY and IMPACT remain robust.Footnote 115 In all models, we find again that IMPARTIALITY is consistently negatively correlated with EXPERT AUTHORITY and that the coefficients are relatively small and statistically insignificant. Regarding IMPACT, we observe that it is consistently positively correlated with EXPERT AUTHORITY, that its coefficients are the largest in size and are all statistically significant. In Models 4, 6, and 8, IMPACT is the only variable that is statistically significant. This increases confidence in the findings from Models 1 and 2, namely that IMPACT is associated with de facto EXPERT AUTHORITY, while IMPARTIALITY is not.

In contrast, the results for OBJECTIVITY and ASYMMETRY differ among the subsamples. In this regard, Models 3–8 allow us to specify the relationship between OBJECTIVITY and EXPERT AUTHORITY, on the one hand, and ASYMMETRY and EXPERT AUTHORITY, on the other. Both only correlate with de facto expert authority when the IOs to which international bureaucracies belong are perceived to have a rather low coercive potential (Model 3), when the international bureaucracies’ advice is perceived to be congruent with national preferences (Model 6), or when the policy units of ministries do not feel (strongly) pressured by other actors to act on the advice of an international bureaucracy (Model 7). In the three other subsamples, the correlations are statistically insignificant.

Robustness of the results

This article conducted theory-guided tests by means of regression analyses. We used a range of control variables to filter out the effect of potential confounders, and we performed a series of robustness checks in order to increase the validity of our results (see Appendix H in the supplementary material). Robustness tests included an ordered logistic regression for Models 1 and 2 that confirms the results from the OLS regression. Given the (slightly) diverging response rates in the different regions and thematic areas, we used non-response-adjusted survey weights. This did not change key estimates; only some of the coefficient values changed and by not more than 0.1. We also estimated our models with standard errors clustered at the country level instead of the respondent level, and we included further control variables at the country level in our models. The results remained similar. Finally, we calculated the variance inflation factor (VIF) to rule out multicollinearity. For each of our explanatory variables, the VIF is less than 2. Consequently, multicollinearity is unlikely to influence our results in a substantive way.

Conclusion

Using novel survey data, this article showed that international bureaucracies enjoy varying degrees of de facto expert authority among policy units in ministries. The analysis sought to explain this variation and evaluate the explanatory power of established assumptions. While IO scholars have for long claimed to know why international bureaucracies enjoy expert authority, we found substantial empirical support for some but not other arguments. First, our core finding is that international bureaucracies enjoy expert authority among policy units in national ministries mainly when they are perceived to effectively address global challenges, to which we referred as perceived impact. This finding was robust to various alternative specifications. It holds independent of existing peer-pressure on states, in the absence and presence of coercive potential, and irrespective of whether international bureaucracies provide advice that is in line with national preferences. Second, we found no empirical evidence that perceptions of international bureaucracies’ impartiality affect their de facto expert authority. This is not to say that impartiality is irrelevant for international bureaucracies, per se. It appears plausible that impartiality matters much more when it comes to authority relations with other audiences, such as societal actors. For the literature on (international bureaucracies’) expert authority, this is a surprising finding. Typically, scholars assume that subordinates do not defer to sources they regard as partisan. Third, the findings for both objectivity and knowledge asymmetry depend on the composition of the sample, for instance, the presence or absence of peer pressure. Both correlate with de facto expert authority only when the IO to which the international bureaucracy belongs has low coercive potential, when peer pressure is perceived to be low, or when the international bureaucracy's advice is perceived to be in line with national domestic preferences. The opposite constellation is a likely candidate for politicisation. Thus, whereas the previous literature has regarded objectivity as a shield against politicisation and hence an important source of international bureaucracies’ authority, our research leads us to the proposition that objectivity might not be enough of a shield for coercive IOs. These still may enjoy expert authority but need to have a reputation of being impactful.

Our analysis refers to a specific group of subordinate actors: national ministries. We do not know whether expert authority follows similar patterns with other relevant stakeholders such as citizens or politicians. However, considering the importance of national administrations as gatekeepers and domestic intermediaries for international bureaucracies’ policy advice, our findings are particularly relevant for debates on the national influence of IOs.

Despite the focus on one stakeholder group, the implications our research implies for IOs that seek to preserve their expert authority, in times of contested multilateralism,Footnote 116 are clear. If international bureaucracies want ministerial units to follow their advice, they should emphasise their record as effectively addressing global challenges, as this is the only aspect that holds for all international bureaucracies, irrespective of other circumstances. It is also the only aspect that is important when international bureaucracies are at risk of being politicised, that is, when they belong to IOs with high coercive potential, when they provide advice that tends to be less congruent with national policy preferences, and when third-party actors exert pressure to act on their advice. Second, those international bureaucracies that cannot rely on other means of inducing deference should ensure that they are able to present their work as objective. By doing so, they can preserve the heart of their bureaucratic power.

Acknowledgements

We thank the RIS editors, three anonymous reviewers, Martin Binder, Thomas Diez, Thomas Dörfler, Matthias Ecker-Ehrhardt, Steffen Eckhard, Mirko Heinzel, Anja Jetschke, Pekka Kettunen, Martin Koch, Julia Leib, Nina Reiners, Henning Schmidtke, Duncan Snidal, Matthew Stephens, and Alexandros Tokhi for their helpful comments. Earlier versions of this article were presented at the ECPR General Conference in 2016 and 2017, the ISA Annual Convention in 2017, and the EISA Pan-European Conference on International Relations in 2017, and we are grateful to participants for their comments. We also thank our survey respondents. Finally, we thank Benedict Bueb, Mamy Dioubaté, Serene Hanania, Luise Köcher, Sascha Riaz, Dunja Said, and Antje Specht for research assistance and support in conducting the survey.

The opinions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Deutsche Bundesbank, the Eurosystem, or any other institution with which any of the authors are currently affiliated. All remaining errors are our own.

Funding by the German Research Foundation (DFG) as part of the Research Unit FOR#1745 ‘International Public Administration (IPA)’ with Grant No. LI 1947/1-1 is gratefully acknowledged.

Supplementary material

To view the online supplementary material, please visit: https://doi.org/10.1017/S026021052100005X