Abstract

Purpose

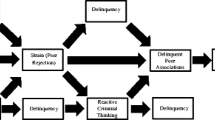

Among identity theories of desistance, there is a discrepancy over the causal ordering of subjective and social factors that lead to desistance. Adding to a limited body of empirical research on the developmental process of desistance early in the life course, the present study examines the interrelationships between the subjective mechanisms of identity and resistance to peer influence and the social mechanism of peer antisocial influence and their direct and indirect effects on desistance.

Methods

Employing 11 waves of data from the Pathways to Desistance Study, the current study uses a random intercepts cross-lagged panel model (RI-CLPM) to account for between-person differences and isolate within-person interrelationships between identity, resistance to peer influence, peer antisocial influence, and delinquency.

Results

Accounting for between-individual differences, results indicate significant stability in all variables, and significant same-wave associations between all variables. Reciprocal cross-lagged effects were found between resistance to peer influence and identity, and between identity and delinquency. Additionally, peer antisocial influence exhibited a significant cross-lagged effect on delinquency, and delinquency exhibited a significant cross-lagged effect on resistance to peer influence. A significant indirect pathway was detected from resistance to peer influence to delinquency through identity.

Conclusions

Findings support prior research and programmatic efforts to promote positive self-identity formation and reduce peer antisocial influence to directly encourage desistance and to promote problem-solving skills in peer contexts to indirectly foster desistance. As social and subjective factors are associated within wave, but not over time, future tests may need to examine desistance processes and the links between subjective and social factors over shorter time frames.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

For violent offenders, the average peak age is slightly older, at 18 years for males and 20 years for females. Non-violent offenders tend to peak at a younger age—17 years for males and 16 years for females [16].

It is important to note that because the quantitative literature on identity’s role in desistance is rather new, each study outlined in this section created its own measures of identity. As research in this area persists, it is possible that scales may become validated.

The dichotomized “family man” variable represents individuals who stated they were good providers, good fathers, and/or good partners [35].

Crank [12] used data derived from the RAND survey (see [26]). Participants were asked, “During the street months on the calendar, which of the following best describe the way you thought of yourself? Answer yes or no for each one” (p. 7). Addict identity was derived from a single item: drug user/addict. Violent identity consisted of two items: fighter/street fighter and violent person. Thief identity was described by two items: thief and burglar. Lastly, straight identity was created from one item: straight/non-criminal.

Paternoster et al. [51] surveyed incarcerated individuals before and after they were released from prison. During both interviews, participants were asked whether they considered themselves an addict. A series of dummy variables were created: never an addict, new addict, and reformed addict; with persistent addict as the reference category.

Importantly, this would also immensely simplify tests and presentation of indirect effects of identity, resistance to peer influence, peer antisocial influence, and delinquency on one another.

Correlations among the variety count measure of delinquency ranged between 0.38 (T9 to T10) and 0.53 (T3 to T4).

To be clear, a p value greater than the alpha level suggests no significant difference in fit between the models and thus a preference of the simpler model on the basis of parsimony.

Stability paths, correlated changes, and cross-lagged effects were similar in a model that did not constrain the grand means to equality over time.

References

Bentler, P. M. (1990). Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin, 107, 238–246.

Berrington, A., Smith, P., & Sturgis, P. (2006). An overview of methods for the analysis of panel data. ESRC National Center for Research Methods Briefing Paper.

Berry, D., & Willoughby, M. T. (2017). On the practical interpretability of cross-lagged panel models: rethinking a developmental workhorse. Child Development, 88, 1186–1206.

Bollen, K. A., & Pearl, J. (2013). Eight myths about causality and structural equation models. In S. L. Morgan (Ed.), Handbook of causal analysis for social research (pp. 301–328). New York: Springer.

Brame, R., Fagan, J., Piquero, A., Schubert, C., & Steinberg, L. (2004). Criminal careers of serious delinquents in two cities. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice, 2, 256–272.

Bushway, S. D., & Paternoster, R. (2014). Identity and desistance from crime. In J. A. Humphrey & P. Cordella (Eds.), Effective interventions in the lives of criminal offenders (pp. 63–77). New York: Springer.

Bushway, S. D., Thornberry, T. P., & Krohn, M. D. (2003). Desistance as a developmental process: a comparison of static and dynamic approaches. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 19, 129–153.

Campbell, D. T., & Fiske, D. W. (1959). Convergent and discriminant validation by the multitrait-multimethod matrix. Psychological Bulletin, 56, 81–105.

Caspi, A., & Moffit, T. E. (1993). When do individual differences matter? A paradoxical theory of personality coherence. Psychological Inquiry, 4, 247–271.

Cirino, P. T., Chin, C. E., Sevcik, R. A., Wolf, M., Lovett, M., & Morris, R. D. (2002). Measuring socioeconomic status: reliability and preliminary validity for different approaches. Assessment, 9(2), 145–155.

Collins, W. A., & Steinberg, L. (2008). Adolescent development in interpersonal context. In W. Damon & R. M. Lerner (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology (pp. 551–590). Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons.

Crank, B. R. (2016). Accepting deviant identities: the impact of self-labeling on intentions to desist from crime. Journal of Crime and Justice, 1–18.

Dumas, T. M., Ellis, W. E., & Wolfe, D. A. (2012). Identity development as a buffer of adolescent risk behaviors in the context of peer group pressure and control. Journal of Adolescence, 35, 917–927.

Erikson, E. (1968). Identity: Youth ad crisis. New York: Norton.

Fader, J. (2013). Falling back: incarceration and transitions to adulthood among urban youth. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.

Farrington, D. P. (1986). Age and crime. Crime and Justice, 7, 189–250.

Giordano, P. C., Cernkovich, S. A., & Rudolph, J. L. (2002). Gender, crime, and desistance: toward a theory of cognitive transformation. American Journal of Sociology, 107(4), 990–1064.

Giordano, P. C., Schroeder, R. D., & Cernkovich, S. A. (2007). Emotions and crime over the life course: a neo-median perspective on criminal continuity and change. American Journal of Sociology, 112(6), 1603–1611.

Granic, I., & Patterson, G. R. (2006). Toward a comprehensive model of antisocial development: a dynamic systems approach. Psychological Review, 113, 101–131.

Greenberger, E., & Bond, L. (1976). Technical manual for the Psychosocial Maturity Inventory. Unpublished manuscript, Program in Social Ecology. Irvine: University of California.

Greenberger, E., Josselson, R., Knerr, C., & Knerr, B. (1974). The measurement and structure of psychosocial maturity. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 4, 127–143.

Hamaker, E., Kuiper, R., & Grasman, R. (2015). A critique of the cross-lagged panel model. Psychological Methods, 20, 102–116.

Hirschi, T., & Gottfredson, M. (1983). Age and the explanation of crime. American Journal of Sociology, 89(3), 552–584.

Hoeben, E. M., Meldrum, R. C., Walker, D., & Young, J. T. N. (2016). The role of peer delinquency and unstructured socializing in explaining delinquency and substance use: a state-of-the-art review. Journal of Criminal Justice, 47, 108–122.

Hollingshead, A. B. (1957). Two factor index of social position. New Haven: Yale University.

Horney, J., & Marshall, I. H. (1993). Crime commission rates among incarcerated felons in Nebraska, 1986-1990. [Computer file]. Ann Arbor: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research.

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6, 1–55.

Huizinga, D., Esbensen, F., & Weiher, A. (1991). Are there multiple paths to delinquency? Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology, 82, 83–118.

Keijsers, L. (2016). Parental monitoring and adolescent problem behaviors: How much do we really know? International Journal of Behavioral Development, 40, 271–281.

King, S. (2013). Early desistance narratives: a qualitative analysis of probationers’ transitions towards desistance. Punishment & Society, 15(2), 147–165.

Kline, R. B. (2005). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Guilford.

Krohn, M. D., Gibson, C. L., & Thornberry, T. P. (2013). Under the protective bud the bloom awaits: a review of theory and research on adult-onset and late-blooming offenders. In C. L. Gibson & M. D. Krohn (Eds.), Handbook of life-course criminology: emerging trends and direction for future research (pp. 183–200). New York: Springer.

Laub, J. H., & Sampson, R. J. (2001). Understanding desistance from crime. Crime and Justice: A Review of Research, 28, 1–70.

Laub, J. H., & Sampson, R. J. (2003). Shared beginnings, divergent lives: delinquent boys to age 70. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Lebel, T. P., Burnett, R., Maruna, S., & Bushway, S. (2008). The ‘chicken and egg’ of subjective and social factors in desistance from crime. European Journal of Criminology, 5(2), 131–159.

Marshall, A. (2012). Adolescent and adult offender recidivism rates after cognitive behavioural therapy: a comparison using meta-analysis (Masters dissertation). Retrieved from University of Leicester Research Archive.

Maruna, S. (2001). Making good: how ex-offenders reform and reclaim their lives. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association Books.

Maruna, S., & Roy, K. (2007). Amputation or reconstruction?: notes on the concept of “knifing off” and desistance from crime. Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice, 23(1), 104–124.

Meldrum, R. C., Miller, H. V., & Flexon, J. L. (2013). Susceptibility to peer influence, self-control, and delinquency. Sociological Inquiry, 83(1), 106–129.

Meredith, W. (1993). Measurement invariance, factor analysis and factorial invariance. Psychometrika, 58, 525–543.

Monahan, K. C., & Piquero, A. R. (2009). Investigating the longitudinal relation between offending frequency and offending variety. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 36(7), 653–673.

Monahan, K. C., Steinberg, L., & Cauffman, E. (2009a). Affiliation with antisocial peers, susceptibility to peer influence, and antisocial behavior during the transition to adulthood. Developmental Psychology, 45(6), 1520–1530.

Monahan, K. C., Steinberg, L., Cauffman, E., & Mulvey, E. P. (2009b). Trajectories of antisocial behavior and psychosocial maturity from adolescence to young adulthood. Developmental Psychology, 45(6), 1654–1668.

Monahan, K. C., Steinberg, L., Cauffman, E., & Mulvey, E. P. (2013). Psychosocial (im)maturity from adolescence to early adulthood: distinguishing between adolescence-limited and persisting antisocial behavior. Development and Psychopathology, 25, 1093–1105.

Mulvey, E. P. (n.d.). Research on pathways to desistance [Maricopa County, AZ and Philadelphia County, PA]: subject measures, 2000-2010. Ann Arbor: ICPSR.

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. 1998-2016. Mplus user’s guide, 7th edn. Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén.

Na, C., Paternoster, R., & Bachman, R. (2015). Within-individual change in arrests in a sample of serious offenders: the role of identity. Juvenile Developmental Life Course Criminology, 1, 385–410.

Osgood, D. W., Wilson, J. K., O’Malley, P. M., Bachman, J. G., & Johnston, L. D. (1996). Routine activities and individual deviant behavior. American Sociological Review, 61, 635–655.

Paternoster, R., & Bushway, S. (2009). Desistance and the “feared self”: toward an identity theory of criminal desistance. The Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology, 99(4), 1103–1156.

Paternoster, R., Bachman, R., Bushway, S., Kerrison, E., & O’Connell, D. (2015). Human agency and explanations of criminal desistance: arguments for a rational choice theory. Journal of Developmental Live Course Criminology, 1, 209–235.

Paternoster, R., Bachman, R., Kerrison, E., O’Connell, D., & Smith, L. (2016). Desistance from crime and identity: an empirical test with survival time. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 43(9), 1204–1224.

Piquero, A. R. (2008). Taking stock of developmental trajectories of criminal activity over the life course. In A. M. Liberman (Ed.), The long view of crime: a synthesis of longitudinal research (pp. 23–78). New York, NY: Springer.

Porporino, F. J. (2012). Bringing sense and sensitivity to corrections: from programmes to “fix” offenders to services to support desistance. In J. Brayford, F. Cowe, & J. Deering (Eds.), What else works? Creative work with offenders (pp. 61–85). New York: Routledge.

Porporino, F. J., & Fabiano, E. (2005). Is there an evidence base supportive of women-centered programming in corrections? Corrections Today, 67(6), 26–28.

Pratt, T. C., Cullen, F. T., Sellers, C. S., Winfree, T. L., Jr., Madensen, T. D., Daigle, L. E., Fearn, N. E., & Gau, J. M. (2010). The empirical status of social learning theory: a meta-analysis. Justice Quarterly, 27(6), 765–802.

Rocque, M., Posick, C., & White, H. R. (2015). Growing up is hard to do: an empirical evaluation of maturation and desistance. Journal of Developmental Life Course Criminology, 1, 350–384.

Rocque, M., Posick, C., & Paternoster, R. (2016). Identities through time: an exploration of identity change as a cause of desistance. Justice Quarterly, 33(1), 45–72.

Sampson, R. J., & Laub, J. H. (1993). Crime in the making: pathways and turning points through life. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Sampson, R. J., & Laub, J. H. (2005). A life-course view of the development of crime. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 602(12), 12–45.

Schubert, C. A., Mulvey, E. P., Steinberg, L., Cauffman, E., Losoya, S. H., Hecker, T., Chassin, L., & Knight, G. P. (2004). Operational lessons from the pathways to desistance project. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice, 2(3), 237–255.

Selig, J. P., & Little, T. D. (2012). Autoregressive and cross-lagged panel analysis for longitudinal data. In B. Laursen, T. D. Little, & N. A. Card (Eds.), Handbook of developmental research methods. Guilford Press.

Slagt, M., Dubas, J. S., Dekovic, M., Haselager, G. J. T., & Van Aken, M. A. G. (2015). Longitudinal associations between delinquent behaviour of friends and delinquent behaviour of adolescents: moderation by adolescent personality traits. European Journal of Personality, 29, 468–477.

Steiger, J. H., & Lind, J. (1980). Statistically-based tests for the number of common factors. In Paper presented at the Annual Spring Meeting of the Psychometric Society, Iowa City.

Steinberg, L. (2014). Age of opportunity: lessons from the new science of adolescence. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Steinberg, L., & Cauffman, E. (1996). Maturity of judgment in adolescence: psychosocial factors in adolescent decision making. Law and Human Behavior, 20(3), 249–272.

Steinberg, L., & Monahan, K. C. (2007). Age differences in resistance to peer influence. Developmental Psychology, 43(6), 1531–1543.

Steinberg, L., & Silverberg, S. B. (1986). The vicissitudes of autonomy in early adolescence. Child Development, 57(4), 841–851.

Sumter, S. R., Bokhorst, C. L., Steinberg, L., & Westenberg, P. M. (2009). The developmental pattern of resistance to peer influence in adolescence: will the teenager ever be able to resist? Journal of Adolescence, 32, 1009–1021.

Thornberry, T. P., Lizotte, A. J., Krohn, M. D., & Farnworth, M. (1994). Delinquent peers, beliefs, and delinquent behavior: a longitudinal test of interactional theory. Criminology, 32, 47–84.

Weinberger, D.A., and Schwartz, G.E. (1990). Distress and restraint as superordinate dimensions of self-reported adjustment: A typological perspective. Journal of Personality, 58(2), 381–417.

Walden, T., Harris, V., Weiss, B., & Catron, T. (1995). Telling what we feel: Self-reports of emotion regulation and control among grade school children. Paper presented at the Biennial Meeting of the Society for Research in Child Development, Indianapolis, IN.

Wechsler, D. (1999). Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence. The Psychological Corporation: Harcourt Brace & Company. New York, NY.

Hamaker, E. (2018). How to run the RI-CLPM with Mplus. Retrieved from https://www.statmodel.com/download/RI-CLPM%20Hamaker%20input.pdf. Accessed 1 May 2018.

Ciocanel, O., Power, K., Eriksen, A., & Gillings, K. (2017). Effectiveness of positive youth development interventions: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Journal of Youth Adolescence, 46(3), 483–504. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-016-0555-6.

Tucker, L. R., & Lewis, C. (1973). A reliability coefficient for maximum likelihood factor analysis. Psychometrika, 38, 1–10.

Warr, M. (1998). Life-course transitions and desistance from crime. Criminology, 36, 183–216.

Wolfe, D. A., Crooks, C. V., Chiodo, D., Hughes, R., & Ellis, W. (2012). Observations of adolescent peer resistance skills following a classroom-based healthy relationship program: a post-intervention comparison. Prevention Science, 13(2), 196–205.

Shulman, E. P., Smith, A. R., Silva, K., Icenogle, G., Duell, N., Chein, J., & Steinberg, L. (2016). The dual systems model: Review, reappraisal, and reaffirmation. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience, 17, 103–117.

Weinberger, D.A., and Schwartz, G.E. (1990). Distress and restraint as superordinate dimensions of self-reported adjustment: A typological perspective. Journal of Personality, 58(2), 381-417.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Forney, M., Ward, J.T. Identity, Peer Resistance, and Antisocial Influence: Modeling Direct and Indirect Causes of Desistance. J Dev Life Course Criminology 5, 107–135 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40865-018-0102-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40865-018-0102-0