Abstract

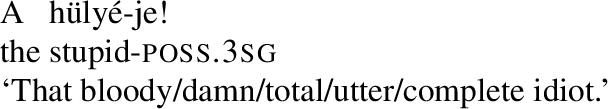

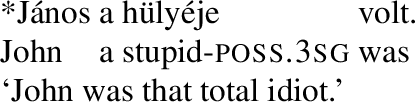

The non-possessive uses of possessive morphology in Uralic languages have been a topic of intense debate (Fraurud 2001; Nikolaeva 2003; Gerland 2014; Janda 2015; É. Kiss and Tánczos to appear). In this paper, I focus on a special use of the poss.3sg suffix in Hungarian constructions such as a hülyéje (the stupid-poss.3sg): lit. ‘its stupid’, meaning ‘that total idiot’. My main claim is that this suffix is an affective demonstrative suffix (Lakoff 1974; Liberman 2008; Potts and Schwarz 2010), and that it has developed as a result of grammaticalization from a full-fledged possessive construction of the form a világ hülyéje (the world stupid-poss.3sg): lit. ‘the world’s stupid’, meaning: ‘the biggest idiot in the world’. I will show that this gradual process can be reconstructed fairly accurately using historical and contemporary corpora. I also claim that this grammaticalization pathway is very natural as it is based on a set-element relationship which is often expressed by possessive constructions cross-linguistically. I also identify two parameters which facilitate this grammaticalization process: the availability of (silent) pro possessors and the lack of gender agreement on the possessive suffix. Since Uralic languages in general have these parameters, I will argue that this grammaticalization pathway should at least be considered as one of the possible sources of the demonstrative (and definiteness marking) uses of poss.3sg suffixes in Uralic languages. Finally, my results are also an important contribution to the debate on whether demonstratives can be derived from other functional elements through grammaticalization (Plank 1979; Traugott 1982; Himmelmann 1997).

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Glosses are provided in adherence to the Leipzig Glossing Rules (Bickel et al. 2008). The most important glosses are as follows: 1sg = first person singular, 3sg = third person singular, 3pl = 3rd person plural, acc = accusative, dat = dative, ill = illative, inf = infinitive, nad = negative affective demonstrative suffix, pad = positive affective demonstrative suffix, part = partitive suffix, pl = plural, poss = possessedness suffix, prt = verbal particle, sup = superessive.

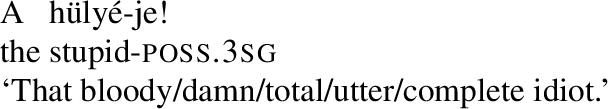

This emphasis is reflected in the fact that the most natural way to translate these phrases into English involves the use of an intensifying adjective such as bloody, damn, total, utter or complete:

-

(i)

For the sake of uniformity, I will use total, which is probably the most neutral of these intensifiers, in the translations.

-

(i)

Bartos (2000, 672) claimed that this use of the poss.3sg suffix is limited to certain idiomatic expressions. This, however, is clearly not the case: this construction can be used with any adjective/noun which can express an emphatically negative evaluation (see datafile).

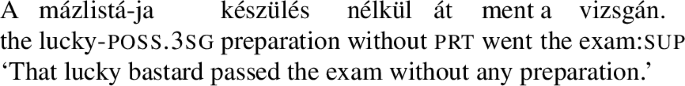

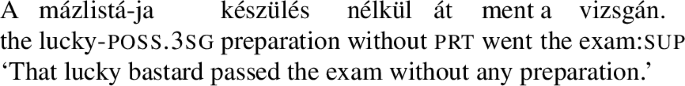

Adjectives connected to luck or good fortune represent an apparent exception to this generalization: they are acceptable even though they are not, at first sight, negative (see also database):

-

(i)

Note, however, that in such sentences too, the speaker expressses an emphatic negative attitude, conveying strong envy and/or the opinion that the good fortunes of the person concerned are undeserved.

-

(i)

In Hungarian, prenominal demonstrative modifiers obligatorily co-occur with the definite article (see Sect. 5.2).

Lakoff (1974) argues that demonstratives have the core function of expressing proximity to/distance from the speaker, whether this proximity is spatio-temporal or emotional.

For a recent overview on the complex topic of vowel harmony in Hungarian, see Rebrus and Törkenczy (2015).

A reviewer notes that since phonologically conditioned vowel alternation is not an absolute rule in Hungarian (i.e., there exist suffixes which are non-alternating), it would be possible for Hungarian to innovate to the hypothetical situation exemplified in (20). That is indeed a technical possibility, however, it would require the suspension of the phonologically conditioned vowel alternation rule with regard to the affective demonstrative suffix and the near-simultaneous innovation of a semantically conditioned vowel alternation rule. My point here is that while the pervasiveness of phonologically conditioned vowel harmony in Hungarian does not strictly speaking rule out the innovation of (20), it certainly makes it very difficult.

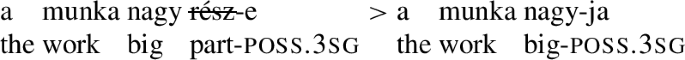

This statement will be qualified in Sect. 5.5 where we discuss grammaticalization-related morphological reduction.

Note that while many languages such as English do not have purely affective demonstratives (that is to say, it is spatial demonstratives which can also be used in an affective function), there are languages noted in the literature which have demonstratives restricted to affective usage. Several Australian languages have such dedicated affective (or recognitional) demonstratives according to Himmelmann (1997, 62–71). Coptic has a series of definite determiners which have been traditionally analyzed as affective demonstratives (Polotsky 1968; Egedi 2017).

Most of my informants have either no or only a passive knowledge of this construction. However, the fact that it does survive synchronically is attested by numerous instances on internet discussion forums.

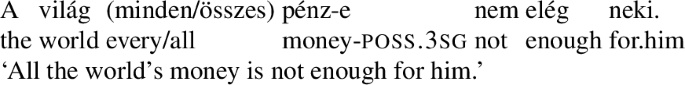

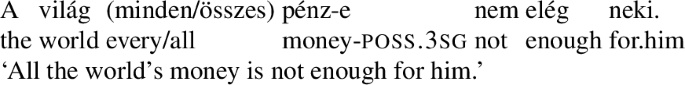

Before we proceed, consider below a construction that may be superficially similar to what we have discussed so far as it also has világ ‘world’ as the possessor:

-

(i)

This construction, while superficially similar, has in fact nothing to do with the constructions under examination in this paper. The possessor is not the world in the abstract sense (totality of individuals) but the physical universe. The ‘possessum’ is not an adjective but a noun, and what the whole construction denotes is not a salient element of a set, but rather, the totality of what is denoted by the possessum (which can be expressed explicitly by optionally inserting a universal quantifier).

-

(i)

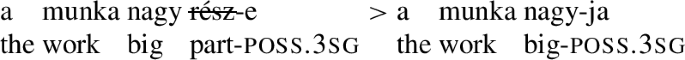

This analysis can be extended to the partitive construction as well (see Sect. 2.5 below):

-

(i)

-

(i)

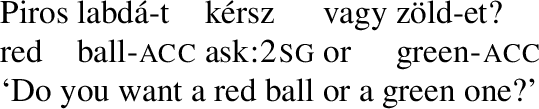

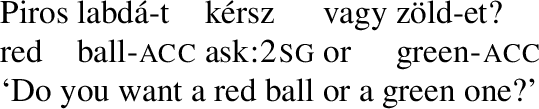

This is not limited to possessive constructions. Consider:

-

(i)

-

(i)

To a very limited degree, this construction is synchronically available with community (or [+human/animate]) possessors as well (see database).

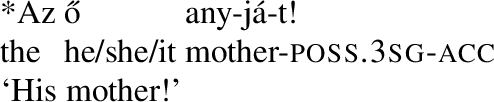

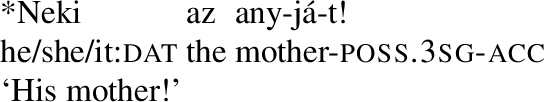

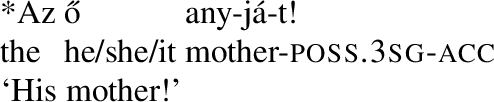

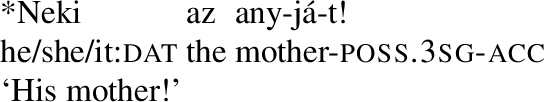

The fact that these swearword exclamations are not possessive constructions is shown by the impossibility of adding to them either a dative-marked or a nominative possessor, i.e. (i) and (ii) cannot be interpreted as swearword exclamations, only as elliptical answers to the question ‘Whose mother?’:

-

(i)

-

(ii)

For a detailed discussion of the possessive in Hungarian see (inter alia): Szabolcsi (1983, 1994), den Dikken (1999), Bartos (1999, 2000), É. Kiss (2002) and Dékány (2011).

-

(i)

For an overview, see Dékány (2011).

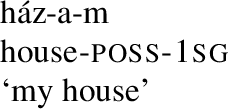

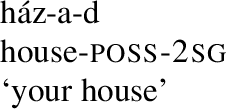

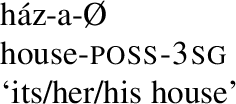

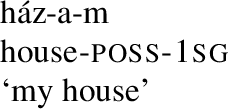

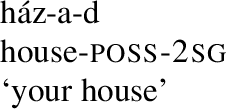

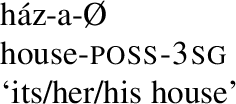

Note that what we gloss in this paper as a ‘3rd person singular possessive suffx’ (poss.3sg) is in fact (simplifying somewhat) a compound of the possessive morpheme (poss) and the phonologically silent 3rd person singular agreement morpheme (3sg). This simplification does not affect the analysis presented in this paper. Consider:

-

(i)

-

(ii)

-

(iii)

-jA is shorthand for the poss.3sg suffix (the capital -A signifying the vowel which can surface either as -a or -e dependeing on the vowel quality of the stem). Note also that Szabolcsi (1994) assumes a phonological rule which deletes the definite article whenever it is followed by a determiner on the surface:

a csapat e három balszerencsés játékosa.

a csapat e három balszerencsés játékosa.-

(i)

Marcel den Dikken (pc) proposed to me an alternative analysis, where phrases such as a hülyé-je (the stupid-poss.3sg) ‘that total idiot’ could be analyzed as predicative copular constructions with the suffix functioning as the copula. Note that Hungarian has an affective construction which has been analyzed in a similar vein (den Dikken 2006):

-

(i)

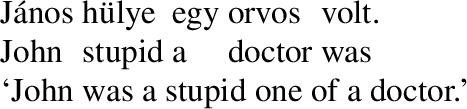

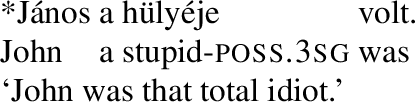

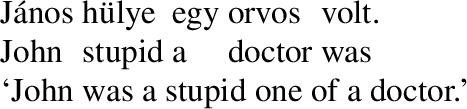

In den Dikken’s analysis, hülye egy orvos ‘a stupid one of a doctor’ is a copular predicative construction with a missing/silent copula. This analysis could be extended to a hülyé-je (the stupid-poss.3sg) ‘that total idiot’ by assuming that (i) it is a predicative copular construction with a silent subject, (ii) the possessive suffix is the overt version of the copula and (iii) its overt presence is required so that it can license an empty subject. While such a unified account would be appealing (see den Dikken (2015) for a copular approach to Hungarian possessedness morphology), I believe it cannot adequately account for a number of empirical observations.

First of all, as we have seen in (5) and (6) above, poss3sg can freely appear in cases where the ‘subject of predication’ is overt, i.e., where there is no need to license a silent subject. Also, in contrast to the negative affective demonstrative construction, the affective construction in den Dikken (2006) is not limited in terms negativity/positivity: hülye egy orvos ‘a stupid one of a doctor’, csodálatos egy tanár ‘a wonderful teacher’, átlagos egy nap ‘an average day’ are all fine: one would expect no such difference if these constructions were underlyingly the same. Furthermore, hülye egy orvos ‘a stupid one of a doctor’ is an indefinite which can be freely used in predicative statement such as (i), the NAD construction, as we have seen in (12), is strictly a definite and cannot be used in a sentence like (i) above:

-

(ii)

Furthermore, the meaning is also different: hülye egy orvos simply means a doctor who is stupid (or someone who is stupid qua doctor), but not necessarily saliently so, the NAD construction refers to someone who is salient in terms of stupidity. Finally, as we will see in Sect. 5.5, the NAD suffix is not identical to the poss.3sg suffix, which can be easily accounted for in a grammaticalization framework, but would be difficult to explain under the assumption that what we see here is the possessive suffix functioning as a copula.

-

(i)

In Hungarian, there are many noun-adjective pairs which sound identical. E.g. marha (noun, ‘literally: cow, figuratively: stupid person’) and marha (adjective, ‘stupid’). This means that a világ marhája may be analyzed in two ways: either as having a noun possessum or having and adjective possessum. Based on (68), however, it seems that only the adjective possessum analysis is appropriate.

Instances with the irregular morphology are sporadically attested, but are vastly outnumbered by instances with the regularized morphology.

References

Baker, M. (1985). The mirror principle and morphosyntactic explanation. Linguistic Inquiry, 16, 373–415.

Bartos, H. (1999). Morfoszintaxis és interpretáció. A magyar inflexiós jelenségek szintaktikai háttere [Morphosyntax and interpretation. The syntactic background of Hungarian inflexional phenomena]. Ph.D. thesis, Budapest: Eötvös University.

Bartos, H. (2000). Az inflexiós jelenségek szintaktikai háttere [The syntactic background of inflexional phenomena]. In F. Kiefer (Ed.), Strukturális magyar nyelvtan 3. Morfológia [Hungarian structural grammar 3. Morphology] (pp. 653–761). Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó.

Bernstein, J. B. (1997). Demonstratives and reinforcers in Romance and Germanic languages. Lingua, 102(2–3), 87–113.

Bickel, B., Comrie, B., & Haspelmath, M. (2008). The Leipzig Glossing Rules. Conventions for interlinear morpheme by morpheme glosses.

Bowdle, B. F., & Ward, G. (1995). Generic demonstratives. In J. Ahlers, L. Bilmes, J. S. Guenter, B. A. Kaiser, & J. Namkung (Eds.), Proceedings of the twenty-first annual meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society (pp. 32–43). Berkeley: Berkeley Linguistics Society.

Collinder, B. (1957). Survey of the Uralic languages. Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell.

Dékány, É. (2011). A profile of the Hungarian DP: The interaction of lexicalization, agreement and linearization with the functional sequence. PhD dissertation, University of Tromsø.

Diessel, H. (1999). Demonstratives: Form, function and grammaticalization. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

den Dikken, M. (1999). On the structural representation of possession and agreement: the case of (anti-)agreement in Hungarian possessed nominal phrases. In I. Kenesei (Ed.), Crossing boundaries (pp. 137–178). Amsterdam: Benjamins.

den Dikken, M. (2006). Relators and linkers: The syntax of predication, Predicate Inversion, and copulas. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Dikken, M. (2015). On the morphosyntax of (in)alienably possessed noun phrases. In K. É. Kiss et al. (Eds.), Approaches to Hungarian: Volume 14: Papers from the 2013 Piliscsaba conference. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Dömötör, A. (2013). Az ó- és középmagyar kori magánéleti nyelvhasználat morfológiailag elemzett adatbázisa. [A morphologically annotated database of Vernacular language use in Old and Middle Hungarian.]. In E. Fazakas et al. (Eds.), Tér, idő és kultúra metszéspontjai a magyar nyelvben. Budapest–Kolozsvár: Nemzetközi Magyarságtudományi Társaság–ELTE Magyar Nyelvtörténeti, Szociolingvisztikai, Dialektológiai Tanszék.

Ďurovič, Ľ. (1992). Typology of Swearing in Slavonic and some Adjacent Languages. In A. Clas et al. (Eds.), Le mot, les mots, les bons mots: hommage à Igor A. Mel’čuk à l’occasion de son soixantieme anniversaire (pp. 39–49). Montréal: Presses de l’Université Montréal.

Eckardt, R. (2006). Meaning change in grammaticalization: an enquiry into semantic reanalysis. London: Oxford University Press.

Egedi, B. (2013). Grammatical encoding of referentiality in the history of Hungarian. In A. Giacolone Ramat et al. (Eds.), Studies in language companion series: Vol. 138. Synchrony and diachrony: a dynamic interface (pp. 367–390). Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Egedi, B. (2014). The DP-cycle in Hungarian and the functional extension of the noun phrase. In K. É. Kiss (Ed.), Oxford studies in diachronic and historical linguistics: Vol. 11. The evolution of functional left peripheries in Hungarian syntax (pp. 56–82). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Egedi, B. (2017). Two kinds of definiteness in Coptic. In D. A. Werning (Ed.), Lingua Aegyptia 25 (pp. 83–99). Hamburg: Widmaier Verlag.

Elekfi, L. (2000). Semantic differences of suffix alternates in Hungarian. Acta Linguistica Hungarica, 47, 145–177.

É. Kiss, K. (2000). The Hungarian NP is like the English NP. In G. Alberti & I. Kenesei (Eds.), Approaches to Hungarian 7: Papers from the Pécs conference (pp. 119–150). Szeged: JATE.

É. Kiss, K. (2002). The syntax of Hungarian. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

É. Kiss, K. (2018). Possessive agreement turned into a derivational suffix. In H. Bartos et al. (Eds.), Boundaries crossed, at the crossroads of morphosyntax, phonology, pragmatics and semantics (pp. 87–105). Dordrecht: Springer.

É. Kiss, K., & Tánczos, O. (to appear). From possessor agreement to object marking: the grammaticalization path of the Udmurt -(j)ez suffix. Ms.

Farkas, J., & Alberti, G. (2016). The relationship between (in) alienable possession and the (three potential) forms of possessed nouns in Hungarian. Linguistica, 56(1), 111–125.

Frajzyngier, Z. (1996). On sources of demonstratives and anaphors. Typological Studies in Language, 33, 169–204.

Fraurud, K. (2001). Possessives with extensive use: a source of definite articles? In I. Baron et al. (Eds.), Dimensions of possession (pp. 243–267). Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Gerland, D. (2014). Definitely not possessed? Possessive suffixes with definiteness marking function. In T. Gamerschlag et al. (Eds.), Frames and concept types: applications in language and philosophy (pp. 269–292). Berlin: Springer.

Giusti, G. (1994). Enclitic articles and double definiteness: A comparative analysis of nominal structure in Romance and Germanic. The Linguistic Review, 11(3–4), 241–256.

Hajdú, P. (1966). Bevezetés az uráli nyelvtudományba [An Introduction to Uralic Linguistics]. Budapest: Tankönyvkiadó.

Hawkins, J. A. (1978). Definiteness and indefiniteness. London: Croom Helm.

Hopper, P. J., & Traugott, E. C. (1993). Grammaticalization. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Himmelmann, N. (1997). Deiktikon, Artikel, Nominalphrase: Zur Emergenz syntaktischer Struktur. Tübingen: Niemeyer.

Janda, G. E. (2015). Northern Mansi possessive suffixes in non-possessive function. ESUKA–JEFUL, 2015(6-2), 243–258.

Kiefer, F. (1985). The possessive in Hungarian: a problem for Natural Morphology. Acta Linguistica Scientiarum Academiae Hungaricae, 35, 139–149.

Lakoff, R. (1974). Remarks on this and that. Chicago Linguistic Society, 10, 345–356.

Leinonen, M. (1998). The postpositive particle -to of Northern Russian dialects, compared with Permic languages (Komi Zyryan). Studia Slavica Finlandensia, 15, 74–90.

Levinson, S. C. (2000). Presumptive meanings: The theory of generalized conversational implicature. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Liberman, M. (2008). Affective demonstratives. Language Log. http://languagelog.ldc.upenn.edu/nll/?p=674.

Nikolaeva, I. (2003). Possessive affixes in the pragmatic structuring of the utterance: evidence from Uralic. In P. Suihkonen et al. (Eds.), Proceedings of the international symposium on deictic systems and quantification (pp. 130–145). Udmurt State University and Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology.

Novák, A., Orosz, G., & Wenszky, N. (2013). Morphological annotation of Old and Middle Hungarian corpora. In P. Lendvai & K. Zervanou (Eds.), Proceedings of the 7th workshop on language technology for cultural heritage, social sciences, and humanities (pp. 43–48). Sofija, Bulgaria: Association for Computational Linguistics.

Ortmann, A., & Gerland, D. (2014). She loves you, -ja -ja -ja: objective conjugation and pragmatic possession in Hungarian. In D. Gerland, C. Horn, A. Latrouite, & A. Ortmann (Eds.), Meaning and grammar of nouns and verbs (pp. 269–313). Düsseldorf: Düsseldorf University Press.

Pais, D. (1922). Régi személyneveink jelentéstana [The Semantics of Personal Names in Old Hungarian]. Magyar Nyelv, 18, 93–99.

Plank, F. (1979). Ikonisierung und De-Ikonisierung als Prinzipien des Sprachwandels. Sprachwissenschaft, 4, 121–158.

Polotsky, H. J. (1968). The ‘weak’ plural article in Bohairic. Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, 54, 243–245.

Potts, C., & Schwarz, F. (2010). Affective ‘this’. Linguistic Issues in Language Technology, 3(5), 1–30.

Prince, E. F. (1981). On the Inferencing of Indefinite-this NPs. In A. K. Joshi, B. L. Webber, & I. A. Sag (Eds.), Elements of discourse understanding (pp. 231–250). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Rebrus, P., & Törkenczy, M. (2015). Monotonicity and the typology of front/back harmony. Theoretical Linguistics, 41(1–2), 1–61.

Rebrus, P., Szigetvári, P., & Törkenczy, M. (2017). Asymmetric variation: Justifying the absence of a possessive allomorph. In A. Nevins & G. Lindsey (Eds.), Sonic signatures.

Rédei, K. (1988). Die syrjänische Sprache. In D. Sinor (Ed.), The Uralic languages (pp. 111–130). Leiden: E. J. Brill.

Roberts, I., & Roussou, A. (2003). Syntactic change: a minimalist approach to grammaticalization. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Sapir, E. (1949). A study in phonetic symbolism. In D. G. Mandelbaum (Ed.), Selected writings of Edward Sapir (pp. 61–72). Berkeley: University of California Press.

Sinor, D. (1978). The nature of possessive suffixes in Uralic and Altaic. Linguistic and literary studies in honor of Archibald A. Hill (pp. 257–266). The Hague: de Gruyter.

Traugott, E. C. (1982). From propositional to textual meanings: Some semantic-pragmatic aspects of grammaticalization. In W. P. Lehmann & Y. Malkiel (Eds.), Perspectives on historical linguistics (pp. 245–271). Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Schlachter, W. (1960). Studien zum Possessivsuffix des Syrjänischen. Berlin: Akademie-Verlag.

Simon, E. (2014). Appendix: Corpus building from Old Hungarian codices. In K. É. Kiss (Ed.), Oxford studies in diachronic and historical linguistics: Vol. 11. The evolution of functional left peripheries in Hungarian syntax (pp. 224–236). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Simon, E., & Sass, B. (2012). Nyelvtechnológia és kulturális örökség, avagy korpuszépítés ómagyar kódexekből [Language technology and cultural heritage: Building a corpus from Old Hungarian codices]. Általános Nyelvészeti Tanulmányok, 24, 243–264.

Szabolcsi, A. (1983). The possessor that ran away from home. The Linguistic Review, 3, 89–102.

Szabolcsi, A. (1994). The noun phrase. In F. Kiefer & K. É. Kiss (Eds.), The syntactic structure of Hungarian (pp. 179–274). San Diego/New York: Academic Press.

Ultan, R. (1978). Size-sound Symbolism. In J. H. Greenberg, C. A. Ferguson, & E. A. Moravcsik (Eds.), Universals of human language 2 (pp. 525–568). Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Westerståhl, D. (1985). Logical constants in quantifier languages. Linguistics and Philosophy, 8(4), 387–413.

Winkler, E. (2001). Udmurt. Languages of the world. München: Lincom Europa.

Winkler, E. (2011). Udmurtische Grammatik. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

Wolter, L. K. (2006). That’s that: The semantics and pragmatics of demonstrative noun phrases. Ph.D. dissertation. UCSC.

Woodworth, Nancy. L. (1991). Sound symbolism in proximal and distal forms. Linguistics, 29, 273–299.

Acknowledgements

I wish to thank Erika Asztalos, Ágnes Bende-Farkas, Éva Dékány, Barbara Egedi, Veronika Hegedűs, Katalin É. Kiss and Marcel den Dikken; the participants of the 2nd Formal Diachronic Semantics Workshop (FoDS2), the 40th Annual Conference of the German Linguistic Society (DGfS 40) and the 18th International Morphology Meeting (IMM18); and two anonymous reviewers and the editor for their helpful comments and advice. This paper was written in the framework of project 112057 of OTKA, the Hungarian National Scientific Research Foundation, and with the support of the postdoctoral grant PPD031/2017 of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Halm, T. From possessive suffix to affective demonstrative suffix in Hungarian: a grammaticalization analysis. Morphology 28, 359–396 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11525-018-9332-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11525-018-9332-4

a csapat e három balszerencsés játékosa.

a csapat e három balszerencsés játékosa.