Abstract

Approaching possession as a phenomenon of the morphology–semantics interface, this paper combines two major perspectives, namely the typological and the semantic perspective. It offers a comprehensive approach that bears on the contrast of semantic and pragmatic possession. After portraying the most essential morphosyntactic strategies of split possession, the lexical distinction of nominal concept types and the resulting representation of non-relational and relational nouns is presented, following the theory of Löbner (2011). This allows to explain the use of a certain construction for a given noun by the mapping of lexical semantics to morphosyntactic realisation.

Semantic possession is understood as involving a relation that is inherent to the meaning of the possessed noun, in the sense that the referent of the noun can only be established if the possessor is specified. In contrast, pragmatic possession implies that the relation POSS is established by the context rather than by the lexical semantics. This opposition enables a fresh look at the morphology of nominal possession under which the notion of (in)alienability is reinterpreted. The morphology of alienable constructions is analysed as establishing pragmatic possession by denoting an operation that shifts the head noun from a sortal to a relational concept. Thus, the innovation of the approach lies in its typologically justified radically compositional nature. It is shown in detail how this general methodical strategy accounts for all essential morphosyntactic oppositions known from the typology of nominal possession.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

This structural definition also includes events that are encoded by deverbal nominalisation, since one or several participants are realised in the same way as an argument of a non-derived noun—at least for most nominalisation patterns (see Koptjevskaja-Tamm 1993 for a comprehensive typology, Smirnova 2015 on English).

The referential argument is also called the external argument of the noun since it can only be realised outside of the NP, for example, by the subject of a predicative construction such as John is her brother.

Many authors refer to the p’or phrase as ‘genitive’. In the present paper, the term genitive is used in its purely morphological sense, that is, for the designated adnominal morphological case found in many languages.

The following abbreviations are used for grammatical categories in glosses: abl ‘ablative’, acc ‘accusative’, cl ‘noun class’, conn ‘connective’, cop ‘copula’, dat ‘dative’, decl ‘declarative mood’, def ‘definite article’, det ‘determiner’, dem ‘demonstrative pronoun’, derel ‘de-relationalisation’, dl ‘dual’, erg ‘ergative’, ep ‘epenthetic consonant’, f ‘feminine’, gen ‘genitive’, imp ‘imperative’, interrog ‘interrogative’, io ‘indirect object’, loc ‘locative’, m ‘masculine’, n ‘neuter’, nom ‘nominative’, nomin ‘nominaliser’, non3rd ‘first or second person’, past ‘past tense’, perf ‘perfective’, pl ‘plural’, p’or ‘possessor’, poss ‘relation of possession’, posscl ‘possessive classifier’, pron ‘personal pronoun’, refl ‘reflexive’, rel ‘relator’, sg ‘singular’, subj ‘subject’, ta ‘tense/aspect’; ‘1’, ‘2’ and ‘3’ represent first, second and third person, respectively. A few construction-specific glosses are explained in the plain text preceding the example.

For this reason the term ‘possession’ is actually a misnomer in that it improperly singles out one instance from a variety of instances of a relation.

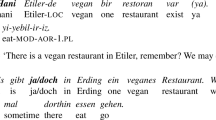

The p’or markers of Yucatec are, according to Lehmann (1998: 33), prenominal clitics (phonologically bound to the preceding word) rather than affixes. That the 3rd person clitic functions as agreement marker is evidenced by its obligatoriness even in the presence of a lexical p’or phrase as in (5a, b).

See Bricker and Po’ot (1998: 358f) for other suffixes with essentially the same function, as well as for further details concerning possession in Yucatec.

Seiler (1983) mentions the Omotic language Dizi as a counterexample to this generalization. However, Claudi and Serzisko (1985) argue in detail for the contrary.

In a way, the East Malayo-Polynesian language Irarutu as described by van den Berg and Matsumura (2008) may constitute an exception, since inalienably possessed nouns bear a person suffix in addition to the person/number prefix they share with alienables. Note, however, that this additional marker merely increases the explicitness in specifying the P’OR, rather than ‘mediating’ between p’um and p’or as relators or classifiers do, which would indeed be unexpected to be only found with inalienables.

As a result, inalienably possessed nouns form a closed class, whereas the class of alienably possessed nouns is open for new items arising from morphological productivity and borrowing (cf. Nichols 1988: 562).

One further pattern involves simultaneous head-marking and dependent-marking and is therefore called ‘double marking’ by Nichols (1986: 65), who mentions Turkish ev-in kapı-sı house-gen door-p’or3sg ‘the door of the house’. More instances are discussed in Koptjevskaja-Tamm (2003: 639–644). For the present scope it is crucial that the double marking strategy is completely independent of the (in)alienability distinction. Notice that Turkish uniformly uses the same construction with all types of nouns. Therefore, neither of the two markers can be associated with the function of a possessive relator.

As for pronominal p’ors, Evans (1995: 204f) notes: “The three-way distinction maintained with noun/adjectives between ablative (possession through inheritance or manufacture), the apposed noun construction (inalienable possession) and the genitive (the unmarked case) is neutralized, with the possessive pronoun being used for all types”; thus: niwanda kirrk ‘his face’, niwanda wunkurr ‘her shelter’, niwanda dulk ‘his country’.

Authier (2013) speaks of these two cases as ‘inlocative’ –a versus ‘adlocative’ –u/-o. He analyses the possession split of Budukh as following the contrast of permanent and non-permanent recipient marking. While the latter contrast is a common East Caucasian feature, reanalysis into an NP-internal contrast of permanent on the one hand and transitory on the other appears to be an exclusive development of Budukh.

As Haude points out, an inalienably possessed noun without a p’or clitic is always understood as being possessed by first person singular, as in (15c). That P’ORs are not expressed when they are first person is a pattern also known from other languages; see Sect. 5.2.1 on ‘possessor deletion’.

Ortmann and Gerland (2014) find that the contrast pertains especially to the class of nouns denoting meronymic artefacts. They propose a compositional semantic analysis of this split which draws a connection to a categorical contrast in the verb agreement, namely that of subjective and objective conjugation.

Alternatively, one could formalise INs and FNs by starting out from their [–U] counterparts, SNs and RNs, and adding the uniqueness condition, thus: λx. SN(x)∧∀y(SN(y)→y = x) and λy.λx. RN(x,y)∧∀z(RN(z,y)→z = x), respectively. See also Sect. 4.3 on the decomposition of RNs and FNs into meaning components.

Note that a purely syntactic version of these states of affairs is offered by Alexiadou (2003), used in order to account for the differences between alienable and inalienable constructions. The template in (28) is parallel to Alexiadou’s phonologically empty functional head ‘Poss’. Accordingly, the structures that Alexiadou puts forward are [DP [D [XP possessed possessor]]] for inalienable and [DP [D PossP [possessor [Poss’ Poss NP]]]] for alienable, respectively.

In a similar vein, in order to relate argument structure to the constituent structure and functional structure of LFG, Bresnan (2001) proposes a lexical predication template that extends the lexical form of a non-relational noun so as to enrich it by a lexical argument structure. Bresnan assumes that non-relational nouns originally do not have a lexical argument structure and on application of the template they have one argument, the P’OR. Under semantic approaches such as the present one, the referential argument of the noun is always counted in, which ensures that [–R] nouns are one-place and possessed nouns are two-place predicates.

See also the account by Le Bruyn et al. (2016). These authors propose an analysis of relational nouns as one-place predicates with an implicit argument, on a par with non-relational nouns that come with an implicit argument due to their qualia structure (l.c.: 51–55; cf. also Le Bruyn and Schoorlemmer 2016: 2–5).

In many languages, definite prenominal p’ors, especially possessive pronouns, trigger a definite (or unique) interpretation of the entire possessed NP. This is also the case in English, provided the NP is in argument position rather than in predicative position (Barker 2011: 1117f). I propose to capture this effect by a type-lifted ‘definite’ variant of (31) as shown in (i).

-

(i)

Possessive pronoun with uniqueness effect

my: [+D] λRC . ιxRC(x, speakerU)

Syntactically, the variant in (i) states that the possessive pronoun is grammaticalised so as to instantiate the category D, that is, to project to DP. Semantically, it is lifted to be a functor over relational concepts (much in the same way as p’ors are under what Partee and Borschev (2003: 75f) call the “uniform argument-only approach”). Applied to (22b) or to (29), it will saturate the P’OR argument and furthermore render the possessive phrase definite, as indicated by the iota operator and the syntactic feature [+D].

-

(i)

Notice that the formulation of the latter constraint relies on the definition of nominal possessive construction given in Sect. 2. This definition comprises any NP construction that expresses a relation between the referential argument of the head noun and another individual introduced by some designated linking means; thus, the constraint applies to [–R] and to [+R] p’um nouns equally.

To account for the unavailability of such sentences in English, Vergnaud and Zubizarreta (1992) assume the following parameter: “The definite determiner may function as an expletive from the point of view of denotation in French but not in English” (1992: 635), the effect being that the English article blocks binding by the phrase-externally realised p’or. See Le Bruyn (2014) for an alternative analysis that bears on the often lexicalised combination of verb and relational noun.

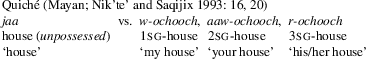

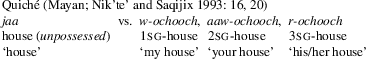

This is not to say that suppletion of noun stems in possessive contexts is only found with kinship terms; neither is it only found with first person. Some Mayan languages such as Tzutujil, Jacaltec and Quiché show a few nouns with a suppletive stem that appears in all possessive contexts, thus, second and third person P’OR just as well as first person. See the contrast in (i):

-

(i)

The point is that in all those cases in which, unlike in Mayan, the distribution of a suppletive noun stem is governed by the person feature of the p’or, it is first person that triggers the suppletion.

-

(i)

Evans (1995) notes that in Kayardild the linear order of p’or and p’um is not fixed in the juxtaposition construction. However, in all the examples he provides the p’or precedes the p’um. In all other possessive constructions referred to as juxtaposition that I am aware of, including the ones of Semitic and Celtic as well as those provided in Sect. 3.1 the word order is set.

Koptjevskaja-Tamm (2003: 634, 645) refers to this type of marker as ‘relator’, whereas I use the term ‘relator’ only for exponents of the operation that establishes the relation POSS in alienable constructions (see the previous subsection).

For an extensive analysis of connectives that are used with modifiers and possessors see den Dikken (2007) and den Dikken and Singhapreecha (2004). These works refer to such markers as ‘linkers’ and analyse them as meaningless elements that show up in syntactic contexts of Predicate Inversion, namely of the P’OR or modifier and the head noun they are predicated of.

The operation corresponds to what is called the ‘detransitivization type-shifter Ex’ by Barker (2011: 1114f), who conceives of it as a silent shifting operator. See also Stiebels (2006: 180f), who labels this operation ‘antipossessive’, and thereby highlights the analogy to the antipassive operation that binds the internal argument of transitive verbs (unlike passive, which binds the external argument).

See also Nichols (1988: 565f) for pertinent examples from Navajo (Athapaskan) and Nanai (Tungusic).

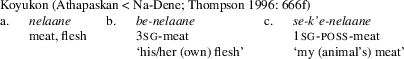

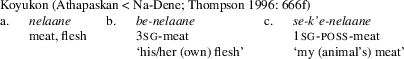

There is intriguing micro-variation in this respect between Slave and its Northern Athapaskan relative Koyukon. In Koyukon, the prefix k’e- fulfils the same de-relational function as Slave ?e-; thus, k’e-tlee’ ‘a head’ (Thompson 1996: 656). However, k’e- is polysemous in that it furthermore denotes the reverse function SN → RC (cf. also Löbner 2011: 325f); thus, an allomorph to the suffix -e’ illustrated in 3.1 and represented in (39). This is obvious from its obligatory occurrence with loan words and game animal nouns if these are combined with a pronominal p’or prefix: se-k’e-deneege ‘my moose’ (Thompson 1996: 667). Now observe the contrast between inalienably and alienably possessed meat in (ib) and (ic).

-

(i)

Evidently, (ic) involves the same sequence of operations as (54c) from Slave. However, unlike bound stems such as -tlee’ ‘head’, nelaane has word status, and it may also occur unpossessed. It follows that contrary to (54c), in (ic) it is the de-relational shift that is covert (as in English), whereas the POSS extension is expressed by k’e.

-

(i)

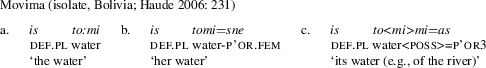

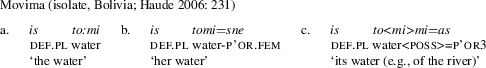

The special situation of Movima is worth mentioning. Most [–R] nouns are simply suffixed by a pronominal clitic in case of pragmatic possession. If, however, an inherent relation between P’OR and P’UM is fancied, this is expressed by infixing reduplication as in (ic).

-

(i)

In this pattern the morphological markedness is the opposite of what we have seen so far. Usually, inherent relations are unmarked and contextual relations are marked; here it is inherent relations that call for markedness.

-

(i)

Notice that a type-shifter analysis of genitive phrases differs from the analysis by Vikner and Jensen (2002: 191, 223), who state: “In cases of inherently non-relational nouns […] we hypothesize that the genitive coerces a shift of the meaning of the head noun so that it becomes relational”. Under this view, the genitive or possessive pronoun themselves do not have the status of an overt operator. Instead, Vikner and Jensen advocate what Partee and Borschev (2003: 79) call the “uniform argument-only approach”, assuming that the p’or phrase as a type-lifted argument coerces the shift, thus, it operates on a [+R] noun rather than producing one.

This formal alternative is also advocated by an anonymous reviewer (Reviewer 2), who notes: “By requiring my to take relations, we can distinguish it from me while at the same time avoiding the problem of needing two lexical entries”. I have in fact made use of this possibility, for one particular configuration: In footnote 18 I propose a type-lifted version of a pronominal p’or, namely λRC. ιxRC(x, speakerU), that is, a functor that takes a relative noun as its argument. Under the radically compositional approach developed here, which builds on the pairing of semantic operations with morphological exponents, this strategy is feasible for languages with a designated possessive pronoun, especially for those in which the possessive pronoun triggers a definite interpretation. In contrast, the strategy is not sufficiently motivated for head-marking languages, in which the possessor markers are identical either to the subject or object markers. For example, in the Mayan languages, the pronominal markers used for possession belong to the same paradigm that specifies the ergative argument, thus, the transitive subject. Here we have little evidence for assuming an additional ‘type-lifted’ entry; instead, there is evidence for the POSS extension on [–R] nouns, namely in the shape of the relator suffix –il (cf. Sects. 3.1 and 5.4.1).

References

Aikhenvald, A. Y. (2013). Possession and ownership: a cross linguistic perspective. In A. Y. Aikhenvald & R. M. W. Dixon (Eds.), Possession and ownership (pp. 1–64). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Aikhenvald, A. Y. & Dixon, R. M. W. (Eds.) (2013). Possession and ownership: a cross-linguistic typology. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Alekseev, M. E. (1994). Part 2, The three Nakh languages and six minor Lezgian languages. R. Smeets (Ed.), North East Caucasian languages, Part 2, The three Nakh languages and six minor Lezgian languages (Vol. 4, pp. 259–296). Delmar: Caravan.

Alexiadou, A. (2003). Some notes on the structure of alienable and inalienable possessors. In M. Coene & Y. D’hulst (Eds.), From NP to DP. Vol 2: The expression of possession in noun phrases (pp. 167–188). Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Alexiadou, A. (2005). Possessors and (in)definiteness. Lingua, 115, 787–819.

Ameka, F. (1996). Body parts in Ewe grammar. In H. Chappell & W. McGregor (Eds.), The grammar of inalienability: a typological perspective on body part terms and the part whole relation (pp. 783–840). Berlin: de Gruyter.

Authier, G. (2013). The origin of two genitive cases and inalienability split in Budukh (East-Caucasian). Faits des Langues, 41, 177–192.

Barker, C. (1995). Possessive descriptions. Stanford: CSLI.

Barker, C. (2011). Possessives and relational nouns. In C. Maienborn, K. von Heusinger, & P. Portner (Eds.), Semantics: an international handbook of natural language meaning (pp. 1109–1130). Berlin: de Gruyter.

Bavin, E. L. (1996). Body parts in Acholi: alienable and inalienable distinctions and extended uses. In H. Chappell & W. McGregor (Eds.), The grammar of inalienability: a typological perspective on body part terms and the part whole relation (pp. 841–864). Berlin: de Gruyter.

Boas, F., & Deloria, E. (1941). Dakota grammar. Washington: National Academy of Sciences.

Bresnan, J. (2001). Lexical functional syntax. Malden: Oxford & Blackwell.

Bricker, V. R., Po’ot, E. Y., & Po’ot, O. D. (1998). A dictionary of the Maya language as spoken in Hocabá, Yucatán, Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press.

Buechel, E. (1939). A grammar of Lakota – The Language of the Teton Sioux Indians. Rosebud, South Dakota: Rosebud Educational Society.

Chappell, H., & McGregor, W. (1996). Prolegomena to a theory of inalienability. In H. Chappell & W. McGregor (Eds.), The grammar of inalienability: a typological perspective on body part terms and the part whole relation (pp. 3–30). Berlin: de Gruyter.

Claudi, U., & Serzisko, F. (1985). Possession in Dizi: inalienable or not? Journal of African Languages and Linguistics, 7, 131–154.

Crowley, T. (1996). Inalienable possession in Paamese grammar. In H. Chappell & W. McGregor (Eds.), The grammar of inalienability: a typological perspective on body part terms and the part whole relation (pp. 383–432). Berlin: de Gruyter.

den Dikken, M. (1997). Introduction. Lingua, 101(3–4), 129–150. Special Issue “The syntax of possession and the verb ‘have’’’, ed. by Marcel den Dikken.

den Dikken, M. (2007). Amharic relatives and possessives: definiteness, agreement, and the linker. Linguistic Inquiry, 38(2), 302–320.

den Dikken, M., & Singhapreecha, P. (2004). Complex noun phrases and linkers. Syntax, 7, 1–54.

Dixon, R. M. W. (2009). Basic linguistic theory. Vol. 2: Grammatical topics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Drossard, W. (2004). Einige ergänzende Bemerkungen zur Dimension der POSSESSION. In W. Premper (Ed.), Dimensionen und Kontinua. Beiträge zu Hansjakob Seilers Universalienforschung (pp. 97–109). Bochum: Brockmeyer.

Ehrich, V., & Rapp, I. (2000). Sortale Bedeutung und Argumentstruktur: ung-Nominalisierungen im Deutschen. Zeitschrift für Sprachwissenschaft, 19, 245–303.

England, N. C. (1983). A grammar of Mam, a Mayan language. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Evans, N. (1995). A grammar of Kayardild. Berlin: de Gruyter.

Fabri, R. (1993). Kongruenz und die Grammatik des Maltesischen, Tübingen: Niemeyer.

Fabri, R. (1996). The construct state and the pseudo-construct state in Maltese. In A. Borg & F. Plank (Eds.), Rivista di Linguistica 8 (pp. 229–244). Special issue “The Maltese noun phrase meets typology”.

Franco, L., Manzini, M. R., & Savoia, L. M. (2015). Linkers and agreement. The Linguistic Review, 32, 277–332.

Grinevald, C. (2000). A morpho-syntactic typology of classifiers. In G. Senft (Ed.), Systems of nominal classification (pp. 50–92). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Haiman, J. (1985). Natural syntax. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Haspelmath, M. (1999). Explaining article-possessor complementarity: economic motivation in noun phrase syntax. Language, 75, 227–243.

Haude, K. (2006). A grammar of Movima. PhD dissertation, University of Nijmegen. Available at http://webdoc.ubn.ru.nl/mono/h/haude_k/gramofmo.pdf.

Heine, B. (1997). Possession. Cognitive sources, forces, and grammaticalization. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Herslund, M., & Baron, I. (2001). Introduction: dimensions of possession. In I. Baron, M. Herslund, & F. Sørensen (Eds.), Dimensions of possession (pp. 1–25). Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Jensen, P. A., & Vikner, C. (2004). The English prenominal genitive and lexical semantics. In J.-Y. Kim, Y. A. Lander, & B. H. Partee (Eds.), Possessives and beyond: semantics and syntax (pp. 3–27). Amherst: GLSA.

Karol, J. S., & Rozman, S. L. (1974). Everyday Lakota. An English-Sioux dictionary for beginners. St. Francis: Rosebud Educational Society.

Khizanishvili, T. (2006). Possession im Georgischen. In T. Stolz & C. Stroh (Eds.), Possession, Quantitative Typologie und Semiotik (pp. 1–76). Bochum: Brockmeyer (= Diversitas Linguarum 11).

Kibrik, A. E. (1994). Khinalug. In R. Smeets (Ed.), The indigenous languages of the Caucasus, Vol. 4: North East Caucasian languages, Part 2, The three Nakh languages and six minor Lezgian languages (pp. 367–406). Delmar: Caravan.

Kiefer, F. (1985). The possessive in Hungarian: a problem for natural morphology. Acta Linguistica Scientiarum Academiae Hungaricae, 35, 139–149.

Koehn, E., & Koehn, S. (1986). Apalai. In D. C. Derbyshire & G. K. Pullum (Eds.), Handbook of Amazonian languages (Vol. 1, pp. 33–127). Berlin: de Gruyter.

König, E. (2001). Internal and external possession. In M. Haspelmath, E. König, W. Österreicher, & W. Raible (Eds.), Language typology and language universals. An international handbook (pp. 970–978). Berlin: de Gruyter.

Koptjevskaja-Tamm, M. (1993). Nominalizations. London: Routledge.

Koptjevskaja-Tamm, M. (1996). Possessive NPs in Maltese: alienability, iconicity, and grammaticalization. In A. Borg & F. Plank (Eds.), Rivista di Linguistica 8 (pp. 245–274). Special issue “The Maltese noun phrase meets typology”.

Koptjevskaja-Tamm, M. (2001). Adnominal possession. In M. Haspelmath, E. König, W. Österreicher, & W. Raible (Eds.), Language typology and language universals. An international handbook. (pp. 960–970). Berlin: de Gruyter.

Koptjevskaja-Tamm, M. (2003). Possessive NPs in the languages of Europe. In F. Plank (Ed.), Noun phrase structure in the languages of Europe (pp. 621–722). Berlin: de Gruyter.

Le Bruyn, B. (2014). Inalienable possession: the status of the definite article. In A. Aguilar-Guevara, B. Le Bruyn, & J. Zwarts (Eds.), Weak referentiality (pp. 311–333). Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Le Bruyn, B., & Schoorlemmer, E. (2016). Possession: puzzles in meaning and form. Lingua, 182, 1–11.

Le Bruyn, B., de Swart, H., & Zwarts, J. (2016). From HAVE to HAVE-verbs: relations and incorporation. Lingua, 182, 49–68.

Lehmann, C. (1998). Possession in Yucatec Maya. München: Lincom Europa.

Lichtenberk, F. (2009). Attributive possessive constructions in Oceanic. In W. McGregor (Ed.), The expression of possession (pp. 249–292). Berlin: de Gruyter.

Löbner, S. (1985). Definites. Journal of Semantics, 4, 279–326.

Löbner, S. (2011). Concept types and determination. Journal of Semantics, 28, 279–333.

Löbner, S. (2013). Understanding semantics (2nd ed.). London: Routledge.

Lyons, C. (1999). Definiteness. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Mahootian, S. (1997). Persian. London: Routledge.

Manzelli, G. (1990). Possessive adnominal modifiers. In J. Bechert, G. Bernini, & C. Buridant (Eds.), Towards a typology of European languages (pp. 63–111). Berlin: de Gruyter.

McGregor, W. (2009a). Introduction. In W. McGregor (Ed.), The expression of possession (pp. 1–12). Berlin: de Gruyter.

McGregor, W. (Ed.) (2009b). The expression of possession. Berlin: de Gruyter.

Miller, A. (2001). A grammar of Jamul Tiipay. Berlin: de Gruyter.

Mithun, M. (1996). Multiple reflections of inalienability in Mohawk. In H. Chappell & W. McGregor (Eds.), The grammar of inalienability: a typological perspective on body part terms and the part whole relation (pp. 633–649). Berlin: de Gruyter.

Mithun, M. (1999). The languages of native North America. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Mosel, U. (1983). Adnominal and predicative possessive constructions in Melanesian languages. Arbeiten des Kölner Universalienprojektes (akup): Vol. 50. Cologne: Institut für Sprachwissenschaft.

Nichols, J. (1986). Head-marking and dependent-marking grammar. Language, 62, 56–119.

Nichols, J. (1988). On alienable and inalienable possession. In W. Shipley (Ed.), In honor of Mary Haas. Haas festival conference on native American linguistics (pp. 557–609). Berlin: de Gruyter.

Nichols, J. (1992). Linguistic diversity in space and time. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Nik’te’, M. J. S. I., & Saqijix, C. D. L. I. (1993). Gramática pedagógica K’ichee’. Guatemala: Universidad Rafael Landívar.

Nikolaeva, I., & Spencer, A. (2013). Possession and modification—a perspective from canonical typology. In D. Brown, M. Chumakina, & G. Corbett (Eds.), Canonical morphology and syntax, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ortmann, A. (2002). The morphological licensing of modifiers. In V. Samiian (Ed.), Proceedings of the western conference on linguistics (Vol. 12, WECOL 2000, pp. 403–414). Fresno: California State University.

Ortmann, A. (2014). Definite article asymmetries and concept types: semantic and pragmatic uniqueness. In T. Gamerschlag, D. Gerland, R. Osswald, & W. Petersen (Eds.), Frames and concept types: applications in language and philosophy (pp. 293–321). Dordrecht: Springer.

Ortmann, A. (2015). Uniqueness and possession: typological evidence for type shifts in nominal determination. In M. Aher, D. Hole, E. Jerabek, & C. Kupke (Eds.), Logic, language, and computation. 10th international Tbilisi symposium on logic, language, and computation, TbiLLC 2013. Gudauri, Georgia, September 23–27, 2013 (pp. 234–256). Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer. Revised Selected Papers.

Ortmann, A., & Gerland, D. (2014). She loves you, -ja -ja -ja: objective conjugation and pragmatic possession in Hungarian. In D. Gerland, C. Horn, A. Latrouite, & A. Ortmann (Eds.), Meaning and grammar of nouns and verbs (pp. 269–313). Düsseldorf: Düsseldorf University Press.

Partee, B. H. (1986). Noun phrase interpretation and type-shifting principles. In J. Groenendijk, D. de Jongh, & M. Stokhof (Eds.), Foundations of pragmatics and lexical semantics (pp. 115–143). Dordrecht: Foris.

Partee, B. H., & Borschev, V. (2003). Genitives, relational nouns, and argument-modifier ambiguity. In E. Lang, C. Maienborn, & C. Fabricius-Hansen (Eds.), Modifying adjuncts (pp. 67–112). Berlin: de Gruyter.

Peters, S., & Westerståhl, D. (2013). Semantics of possessives. Language, 89, 713–759.

Pustejovsky, J. (1993). Type coercion and lexical selection. In J. Pustejovsky (Ed.), Semantics and the lexicon (pp. 73–94). Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Rice, K. (1989). A grammar of Slave. Berlin/New York: de Gruyter.

Seiler, H. (1982). Possessivity, subject and object. Arbeiten des Kölner Universalienprojektes (akup): Vol. 43. Cologne: Institut für Sprachwissenschaft.

Seiler, H. (1983). Possession as an operational dimension of language, Tübingen: Narr.

Seiler, H. (2001). The operational basis of possession. In I. Baron, M. Herslund, & F. Sørensen (Eds.), Dimensions of possession (pp. 27–40). Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Siewierska, A. (2004). Person. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Siloni, T. (1997). Noun phrases and nominalizations. The syntax of DPs. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Smirnova, A. (2015). Nominalization in English: semantic restrictions on argument realization. Linguistic Inquiry, 46, 568–579.

Stassen, L. (2009). Predicative possession. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Stiebels, B. (2006). From rags to riches: nominal linking in contrast to verbal linking. In D. Wunderlich (Ed.), Advances in the theory of the lexicon (pp. 167–234). Berlin: de Gruyter.

Stolz, T. (2004). Possessions in the far North. A glimpse of the alienability correlation in modern Icelandic. In W. Premper (Ed.), UNITYP revisited (pp. 73–96). Bochum: Brockmeyer.

Stolz, T., & Gorsemann, S. (2001). Prenominal possession in Faroese and the parameters of alienability/inalienability. Studies in Language, 25, 557–599.

Stolz, T., Kettler, S., Stroh, C., & Urdze, A. (2008). Split possession. An areal-linguistic study of the alienability correlation and related phenomena in the languages of Europe. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Storto, G. (2004). Possessives in contexts. In J.-Y. Kim, Y. A. Lander, & B. H. Partee (Eds.), Possessives and beyond: semantics and syntax (pp. 59–86). Amherst: GLSA.

Thompson, C. (1996). On the grammar of body parts in Koyukon Athabaskan. In H. Chappell & W. McGregor (Eds.), The grammar of inalienability: a typological perspective on body part terms and the part whole relation (pp. 551–676). Berlin: de Gruyter.

Tozzer, A. M. (1921/1977). A Maya grammar. With bibliography and appraisement of the works noted. New York: Dover.

van den Berg, R., & Matsumura, T. (2008). Possession in Irarutu. Oceanic Linguistics, 47, 213–222.

van Rijn, M. (2016). Locus of marking typology in the possessive NP: a new approach. Folia Linguistica, 50(1), 269–327.

Velazquez-Castillo, M. (1996). The grammar of possession: inalienability, incorporation and possessor ascension in Guarani. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Vergnaud, J.-R., & Zubizarreta, L. M. (1992). The definite determiner and the inalienable constructions in French and English. Linguistic Inquiry, 23, 595–652.

Vermeulen, R. (2005). The syntax of external possession: its basis in theta-theory. PhD Thesis, University College London. Available at http://www.phon.ucl.ac.uk/home/reiko/#PhD_Thesis.

Vikner, C., & Jensen, P. A. (2002). A semantic analysis of the English genitive. Interaction of lexical and formal semantics. Studia Linguistica, 56, 191–226.

Acknowledgements

The work reported here was carried out in the Research Unit FOR 600 “Functional concepts and frames”, member project “Types of nouns and determination across languages”, and subsequently in the Collaborative Research Centre (CRC 991) “The Structure of Representation in Language, Cognition and Science”, both sponsored by the German Research Foundation (DFG). For comments and discussion at various stages of this work I would like to thank Adrian Czardybon, Philipp Elsbrock, Jens Fleischhauer, Doris Gerland, Corinna Handschuh, Jennifer Kohls, Evelyn Kühn, Irini Penki, Leon Stassen, Thomas Stolz, R. D. Van Valin, Jr., and T. Ede Zimmermann. Special thanks go to Sebastian Löbner for his innumerable suggestions. Finally, I am indebted to two anonymous reviewers for their valuable and constructive feedback.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ortmann, A. Connecting the typology and semantics of nominal possession: alienability splits and the morphology–semantics interface. Morphology 28, 99–144 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11525-017-9319-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11525-017-9319-6