INTRODUCTIONFootnote 1

On Saturday, 3 October 1750, a joyful sight greeted the Governor General of Suriname, Johan Jacob Mauricius. Along Paramaribo's Waterkant, the quay adorned with tamarind and orange trees stretching out from the square where the governor's mansion was located, most of the ships ran flags and fired their guns “as if it were the birthday of the Prince”.Footnote 2 However, the occasion of these festivities greatly annoyed the Dutch governor. For several years, Paramaribo had been the scene of a long feud between Mauricius and sections of the planter class well-entrenched in Suriname's governing council. The conflict can be situated in a wider Atlantic moment of Creole triumphalism in which colonial elites started to challenge the political and economic restrictions imposed by their respective motherlands, and would result in the ousting of Mauricius in April 1751.Footnote 3 In this context of increasing political tensions, Johanna Catharina Brouwer (born Bedloo), one of the most vocal members of the opposition and widow of Everhard Brouwer, the recently deceased former captain of the citizens’ guard and member of the governing council, had organized a provocative ball to celebrate the birthday of her five-year-old daughter.Footnote 4 During the rowdy birthday party, which went on well into the night, fireworks and oranges were thrown at the governor's house, soldiers and slaves broke curfews regulating movement in the city at night, and the authorities were taunted and mocked by adults and children. Only at midnight did the bailiff succeed in finally disbanding the riotous birthday party of Brouwer's happy five-year-old. Three days later, the exasperated Mauricius wrote a long report of the incident to the authorities of the Reformed Church and the directors of the Society of Suriname in Amsterdam, in which he warned that “all respect for God and Government has broken down here, how these are being mocked openly, and spat in the face. Yes, how little children and slaves are being taught to cuss at them”.Footnote 5

A long line of social history on medieval and early modern Europe has concentrated on the way in which internal conflict among sections of the ruling classes could open up spaces for wider social explosions, laying bare existing tensions between political and economic elites and subalterns. In this literature, special importance is attached to rites, festivities, and acts of public shaming, such as rough music, as moments in which social norms and barriers were simultaneously revealed and transgressed.Footnote 6 As the reference to the slaves in Mauricius's outcry reminds us, such transgressions were even more dangerous in a plantation colony in which the bedrock of all social relations was slavery. This article takes a thick description of the many social norms invoked and transgressed in the evening of 3 October 1750 as a starting point to examine everyday practices of social control in Paramaribo, the town of five to six thousand inhabitants that stood at the centre of the colonial Suriname's commerce. In particular, it will look at the way in which, in an Atlantic slave port, more familiar and generally applied aspects of enforcing social order – restricting movement, maintaining social distinctions, effecting taboos on interaction – intersected with a process of racialization, by which skin colour itself became a key determinant of one's position in society. Racialization has not been a prominent theme in the study of the Dutch Atlantic.Footnote 7 This dovetails with more general trends in Dutch historiography, which has often treated the social construction of race as a non-issue.Footnote 8 When historians have discussed race at all, they have done so frequently in a way that treats the emergence of phenotypical differences as key markers of distinction as an almost self-explanatory fact. Starting from places where we can see interaction between different social groups at work – from the squares and the loading docks, the bars and the neighbourhood brawls – can help us to look beyond the apparent naturalness of the success of racially segregationist policies pursued by colonial authorities.Footnote 9

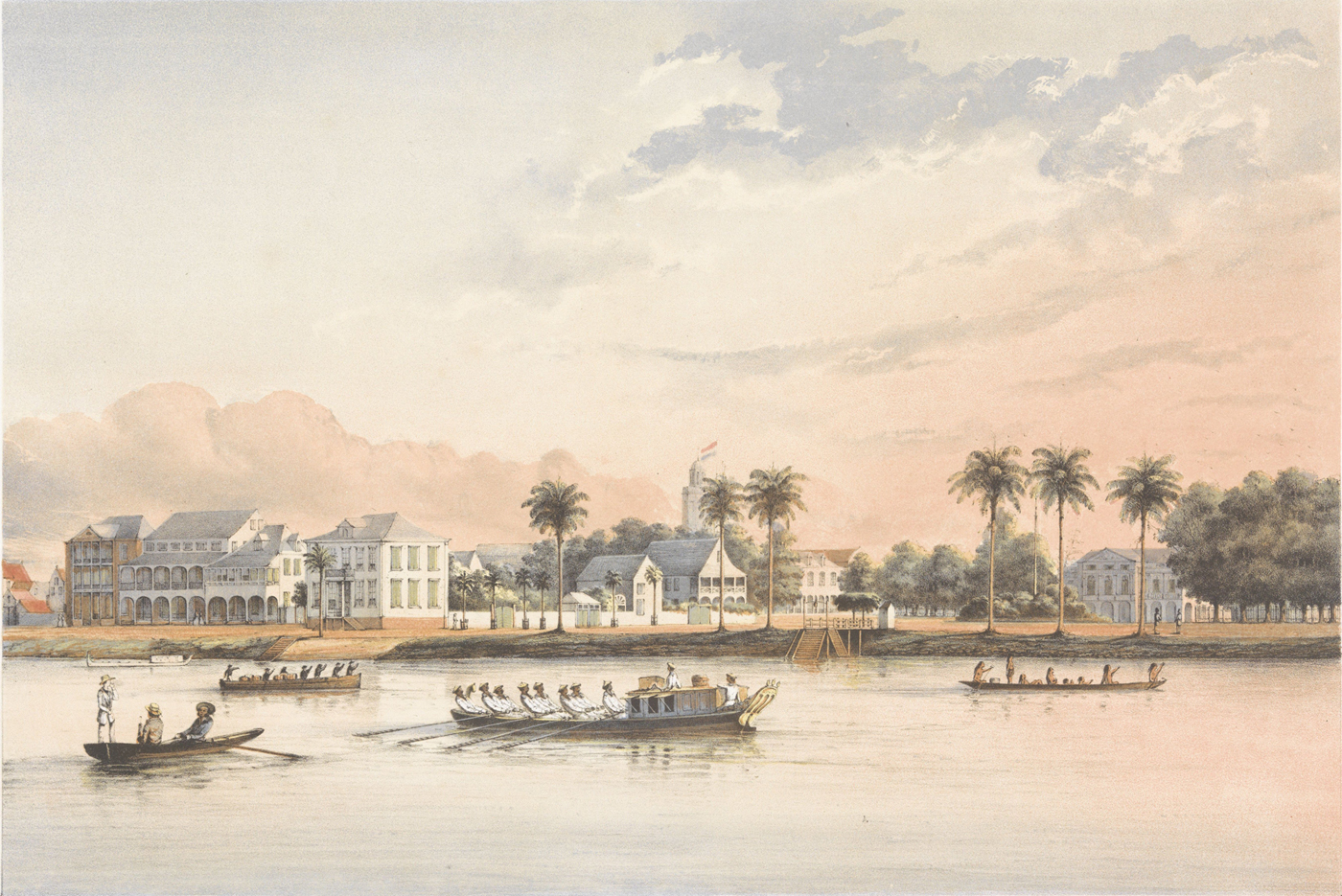

Figure 1. Diorama of the Paramaribo Waterfront (Waterkant), Gerrit Schouten, 1820.

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.

However, choosing the port city as a focal point in this research is not simply a matter of convenience. For understandable reasons, studies of social control in eighteenth-century Suriname have put most emphasis on plantation life.Footnote 10 In the context of the plantation, with its rigid social division between white masters and overseers and the black slaves, outnumbering whites by a ratio of more than ten to one, the almost complete overlap of social and racial distinction hardly appears as strange. The only real question for debate seems to be whether the growing racial exclusivity of plantation slavery was the result of latent prejudices that had always been present in European society, or whether race as a category was created from the outset as an ideological justification for an essentially economic system.Footnote 11 The everyday functioning of social and racial distinctions was much less straightforward in port cities, where intermingling between social groups was extensive and hard to control, movement of people and goods was a given due to their commercial function and geographical location straddling sea and hinterlands, and society was much more socially diverse.Footnote 12 However, the notion of two separated worlds, the static and simple world of the plantation and the complex and dynamic world of the town, is based on an illusion. Constant movement between these worlds was the norm. This included the movement of many slaves, who, individually or in small groups, went to the port for chores, as rowers for the master or his goods, to perform hard labour on the fortress for the government as hired slaves, or to receive punishment. It also included the movement of slaves who had received temporary leave from the plantation to visit their families or sell goods in the market, and of those who had managed to escape and sought refuge in the town. It is exactly this perpetual movement between plantation and port – a crossing of boundaries in its own right – that made towns like Paramaribo focal points for the racialization of social control. Starting from a seemingly innocuous moment of contention, this article tries to capture this process of creating and enforcing boundaries in a sea of movement and intermingling.

DISREPUTABLE DANCES, SWINGING BODIES

What was the Paramaribo in which the widow Johanna Catharina Brouwer organized the “disreputable dance” (in Dutch: eclatant bal) for her daughter, and where did it fit into patterns of colonial sociability? In the decades after the capture of Suriname by a Zeeland fleet in 1667, the Guyana settlement remained a fragile plantation colony built around the three villages Torarica, Jodensavanne, and Paramaribo nearest to the coast. The eighteenth century saw a rapid expansion of the colony's population and a steady growth in its economic importance to the Dutch Republic. Both reached their zenith in the first half of the 1770s. The importance of Paramaribo grew accordingly, while the other two settlements remained villages. By 1752, Suriname had a slave population of 37,835, of whom 2,264 lived in Paramaribo. In the same year, the white, mestizo, and free black population (excluding maroons and the indigenous) numbered 2,062, half of whom lived in Paramaribo. In addition, around 700 soldiers were stationed in Suriname, many of them garrisoned in Fort Zeelandia, which overlooked the Suriname River at the northern edge of Paramaribo.Footnote 13 Beyond Paramaribo, the plantation colony stretched out in two divergent strips along the Suriname and Commewijne Rivers. The middle of the eighteenth century formed a moment of rapid expansion and change, in which the value of coffee exports overtook that of sugar. The steep rise in the number of coffee plantations, from none in 1713 to around 140 by 1745 and 295 around 1770, lay behind the financial boom that made West Indian mortgages all the rage on Amsterdam's capital market.Footnote 14 Dutch Atlantic trade steadily grew to dimensions that rivalled the East India trade, while many other sectors of Dutch capitalism suffered a severe slump.Footnote 15

Figure 2. Top: map indicating the spread of plantations in mid-eighteenth-century Suriname. Bottom: map of Paramaribo including some of the main locations mentioned in this article.

With the growth of the colony, the importance of Paramaribo as a node of urban production and a meeting place for transactions, for gathering news, and for participating in a more diverse social life increased. In this way, in the words of the Surinamese-Dutch scholar Rudolf van Lier, the town “became the centre around which all life in the colony revolved”.Footnote 16 Social and cultural life for the white planter class in Paramaribo included occasional balls of the type organized by the widow of Captain Brouwer, as well as visits to the theatre and the expensive coffee houses and taverns near the waterfront.Footnote 17 When whites went out in the evening, it was not uncommon for them to bring several of their slaves to serve on them.Footnote 18 For masters as well as for large numbers of slaves, though to a lesser extent for the latter owing to their more limited freedom of movement, Paramaribo became an important place of work, where they could obtain news and sometimes drink and socialize around the improvised bars and small shops (vettewariers) that were considered a continuous threat to social order by the colonial authorities.Footnote 19 Fatah-Black details the street peddling done in the town by both slaves and poor whites, and the growth of markets where slaves sold the goods that they produced independently on the kostgronden (provisioning grounds) of the plantations. Markets “were mainly found in the less affluent parts of town, on the square near the church and on the waterfront”.Footnote 20 Of course, Paramaribo was itself an important location for slave labour. Many slaves in Paramaribo were employed as domestic slaves, but occupations also included traditional dock work and labour on the plantations on the outskirt of the town. Slaves carried out tasks for the plantation owners that required a temporary presence in the town, or worked there permanently as carpenters, butchers, or in other types of skilled labour.Footnote 21 Their paths must frequently have crossed those of free blacks and mulattos who carved out their livelihood in Paramaribo, indigenous hunters, white artisans, or sailors and soldiers who worked in town. Waged artisans, crewmen, and slaves often found themselves working side by side on a single project.Footnote 22 Adriaan François Lammens, whose early nineteenth-century description of Suriname gives the most detailed picture of urban life in the colony, describes the scene of work and social and ethnic intermingling along the quay in a passage mixing admiration and class prejudice:

The view of the riverside, where forty to seventy, and sometimes more, seagoing vessels are anchored, is most agreeable: the loading and offloading of the ships, with the continuous coming and going of tent boats, ferries, carrying vessels, and corjaren; the strange sight of Indians, who come to visit Paramaribo; the general activity on the water. A daily, well-stocked fish market opposite the Jewish Broad Street produces an unpleasant sensation for the nostrils, which is not improved by the smells eluded by the working lower class; but one finds for this ample compensation in seeing the abundance of fish, crabs, fruit, and birds available at the market.Footnote 23

Despite this lively portrait, the visible marks of repression and violence were never far off. Fort Zeelandia, which overlooked the governor's mansion, served as the place to which plantation owners had to bring slaves for punishment exceeding the maximum number of lashes they could administer privately. The square between the fortress and the mansion was the place of punishment for soldiers condemned to run the gauntlet.Footnote 24 And a short walk along the Western outskirts of the town brought one to the funeral site reserved for non-whites, as well as the place of execution containing “the remnants of the unlucky ones, who as a warning to others and as punishment for their evil deeds had to end their lives there”.Footnote 25 The close proximity between violence, work, and festivities, both in spatial and in symbolic terms, is well illustrated by a casual remark in the diary of the famed chronicler of the Surinamese Maroon Wars John Gabriel Stedman. On 9 March 1773, he noted:

I return to Paramaribo. N.B. During my absence 3 negroes were hang'd on the boat, and 2 whipt below the gallows. On the 8th [March], being the Prince of Orange his birthday, Colonel Fourgeoud gave a genteel supper and ball to the ladies and gentlemen, la sale de danse [in the] officers’ guardroom.Footnote 26

This, then, was the social and physical environment in which Johanna Catharina Brouwer organized her disreputable dance.Footnote 27 According to Mauricius, when first announced, the plans for the party had already raised a murmur within polite society. The minister of the Reformed Church had ordered the sacristan to inquire with the widow whether she was aware that her ball would be taking place on the night before the Lord's Supper. In answer to these criticisms, Johanna Catharina replied that the ball would only be a children's party.Footnote 28 Persisting against the wishes of the Reformed Church and high society's perceptions of good taste, she asked another widow, her aunt Wossink, for the use of her house. The request was far from innocent, for the house was strategically located between the commander's lodgings and the governor's mansion. It was an excellent place for a spectacle, for the same square also functioned as the parade ground of the garrison of Fort Zeelandia during festivities or official inspections.Footnote 29 Around five in the afternoon of that fateful day, bystanders witnessed the arrival of the guests. These included, in Mauricius's words, “all the children of the Cabal” (meaning the youth from oppositional planter families).Footnote 30 An hour later, to the sound of trumpets, the dance started. To add insult to injury, not long afterwards, one of the prominent guests started throwing fireworks and oranges towards the house of the commander and the governor's mansion, supported by “loud cries of slaves”.Footnote 31

The exact timing of events is important to our understanding of the combination of digressions of the prevailing social order that followed. Mauricius is meticulous in establishing this timeline. According to him, at eight o'clock in the evening the clamour quietened down. Mauricius ascribed this to the fact that regulations prohibited slaves from being on the street without a lantern after this time of night. But shortly after nine, the trumpets started blowing again. This contained a second infringement on lawful restrictions of nightly activities, for among the musicians appeared to be a soldier, the army drummer Lorsius, who was required to be back in his barracks before nine on pain of running the gauntlet.Footnote 32 The latter infringement of discipline provided the pretext for trying to shut the party down. But when Mauricius sent a non-commissioned officer, Hendrik Hop, to arrest Lorsius, the partygoers allowed the soldier to escape through the backdoor. When Hop inquired politely about the drummer, the lady of the house told him that Lorsius had already left by eight, and that “they had no need for soldiers in the house”. After this, she shut the door in Hop's face.Footnote 33

Figure 3. Nineteenth-century view of the government house and adjacent square of Paramaribo, Eduard van Heemskerck van Beest, after Gerard Voorduin, 1860–1862.

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.

The enraged Mauricius sent the bailiff, but he, in turn, was intercepted by Johanna Catharina, who defiantly told him that “the Governor might be master in his house, but she was the master in hers”.Footnote 34 Meanwhile, new musicians had taken the place of the escaped soldier, the most notable of them a violinist referred to as “the young Crepy”, a clerk at the Paramaribo secretariat and son of a prominent planter. One of the most ominous moments of the evening came when this young clerk interrupted the music to shout a mocking challenge to the authorities: “Tomorrow, all the citizens will eat Blakke Breddie”. Employing a phrase in Sranan Tongo or “Negro English”, as the English-based Creole language of Surinamese slaves was then commonly known, this supposedly meant as much as “tomorrow, all the citizens will be in jail”.Footnote 35 It was followed by “Hurrays” taken over by the children. To top it off, a trumpeter “had the temerity to blow on his trumpet, not orderly, but with the most infamous sound in the world, while wenches, children, and slaves loudly laughed and shouted”. The shouts and “mocking trumpet blows” lasted until close to midnight, when Talbot, a member of the government council, came down from Fort Zeelandia and finally managed to disperse the crowd.Footnote 36 In a separate series of comments on the events, added to the official report, Mauricius underlined the reason for his outrage:

To loudly shout under the Governor's windows at night that the citizens will be brought into the fortress in the morning and call out “Hurray!” for this, is such great and coarse rebellion as one can imagine. Just one step further, and the Citizens come and tear the house down.Footnote 37

THE CITIZENS WILL EAT BLAKKE BREDDIE

The “children of the Cabal”, who behaved in such a rowdy way right in front of the governor's house, in fact hailed from the higher echelons of Dutch Surinamese society. All the more powerful therefore was the symbolic inversion of social roles that was implied in the notion that the citizens were jail-bound. Alleging that they had included “Negro English” in their mocking shouts, and to do so in reference to a fortress that also functioned as the central slave prison, further added to the scandalous nature of their utterance. Whether or not Mauricius really believed that the relatively minor infringements that caused him such irritation on the night of 3 October 1750 opened the road to all-out rebellion, his repeated insistence on this in his reports and letters suggests that his superiors in the Dutch Republic would at least recognize the subversive potential of the inversion. Conflicts over class belonging and social status played an important role in the political clashes between increasingly self-confident planters and the governor that divided the colonial state. Behind the anger expressed by each party over the lack of respect shown by the other loomed a greater fear: the existential angst that, while the colonists shouted, the slaves laughed.

Behind the conflicts that erupted in Suriname in the late 1740s ultimately lay economic trends. In order to exploit the opportunities provided by the growing market for Atlantic products in Europe and burgeoning intercolonial trade and smuggling, planters worked to escape the restrictions imposed from above. In 1738, private West Indian traders forced the Dutch West India Company to relinquish its monopoly on the slave trade to Suriname. From the 1740s onwards, a lively legal and illegal trade with the British North American colonies developed that would grow to enormous proportions by the end of the century. As a result, the planters could muster increasing economic power against the governor, who acted as a representative of mercantilist policies enforced by the Society of Suriname, and demanded to be treated with the respect that their wealth in their eyes bestowed upon them.Footnote 38 Economic success also fostered a more assertive attitude towards the motherland. In one of his first petitions to the States General, Samuel du Plessis, one of the most vocal members of the opposition within Suriname's government council, pointed out that “all inhabitants of these lands [i.e. the Dutch Republic], as well as the State itself, would be drawing considerable advantages and prosperity” as a result of the success of the colony.Footnote 39 Suriname planters thus demanded acknowledgement of their role as important contributors to the wealth of the nation. However, colonial governors and their overseas directors tended to see the local elites as rabble and adventurers who had been able to outgrow their proper social sphere to live a life of debauchery in the colony.Footnote 40 A particularly striking example of someone who, in the eyes of Governor Mauricius, had refused to observe the limits imposed by low provenance was Carl Gustav Dahlberg. For the course of events in October 1750, it is significant that, at the time of the scandalous ball, Dahlberg was eating the proverbial black bread. Even more significantly, he was Johanna Catharina Brouwer's lover.

Like many white soldiers and labourers who came to Suriname, Carl Gustav Dahlberg was of non-Dutch origin. In an angry rant in his journal, Mauricius alleged that the Swedish corporal had come to Suriname as part of a transport organized by zielverkopers.Footnote 41 This Dutch term refers to recruiters who used debt traps to force people into the army, the navy, or the service of the colonial companies. Being the victim of a zielverkoper thus automatically designated someone as poor. With some help, once in Suriname Dahlberg had apparently managed to climb to the rank of sub-lieutenant. It was enough of an advance in status for Dahlberg to become an attractive partner for the widow of a member of the government council and plantation owner Johanna Catharina Brouwer, a fact that in itself enraged Mauricius. In the latter's eyes, Dahlberg's engagement with the widow Brouwer, “one of the most impertinent and hellish shrews of the Cabal”, only served him to build his fortune.Footnote 42 Dahlberg would indeed marry Johanna Catharina Brouwer in March 1751, making him the owner of the plantations Brouwershaven and Carlsburg. In 1752, he quit military service and the couple settled in a house in the Heerenstraat in Paramaribo, for which they paid the very high annual rent of 1,000 guilders.Footnote 43 However, as long as he was in the military his love life put him directly at odds with his superiors. On 14 September 1750, his commander had put him under house arrest for unspecified “insolent words”, for which he refused to apologise.Footnote 44 Mauricius was quick to blame the wily ways of women for Dahlberg's behaviour, for “[a]ll his bravado is only to please his Infante”.Footnote 45

Among the oppositionist planters, the arrest became instant proof of the tyrannical mode of operation of the governor and his cronies. In a session of the Military Court on 23 September, four against three council members voted for Dahlberg's release against Mauricius's advice, leading him to overrule the decision and refer the case to a later full session.Footnote 46 In the week that followed, Dahlberg's house was the scene of daily solidarity visits by “the Ladies of the Cabal”, who were received “with music”.Footnote 47 On 3 October, the arrestee even went as far as asking for a temporary release “because he would like to visit the dance” later that night.Footnote 48 Not without reason, Mauricius was convinced that the prime reason behind the provocative gestures that took place at Johanna Catharina Brouwer's party was “that this Amante is piqued by the arrest of her beloved Dahlberg”.Footnote 49

The class anger apparent from Mauricius's comments on the relationship between Dahlberg and Brouwer was wholly in keeping with his general attitude to the oppositionist planters. When first confronted with a petition to the Dutch authorities signed by forty prominent whites, he had used similar slurs to describe his adversaries on the council. He referred to the planter du Plessis as “a raving upstart of a wig-makers apprentice”, Taunay as an “old hunger-comrade”, and the citizens’ captain Amand Thomas as “a real Judas, who in his youth as a regimental barber-surgeon has escaped the gallows twice, now to make his fortune here”.Footnote 50 Whereas Mauricius claimed that the planters blurred social distinctions by rising from rags to riches, the planter oppositionists, in response, charged him with blurring social lines by degrading them in the eyes of ordinary soldiers and slaves. In 1747, sixteen oppositionists, including Taunay, Thomas, and Brouwer (then still alive), complained about Mauricius's pardoning of two deserters who had been sentenced to death. After recalling that the freed soldiers had immediately deserted to a French privateer, they rhetorically asked: “Would it not be better to be a bit more rigorous towards the Soldiers, and a bit less towards Citizens?”.Footnote 51 In a further protest against the “tyrannical regime” of Mauricius, planters retold with even greater indignation the story of a government slave who in the eyes of the opposition had been unjustly released after attacking a free person.Footnote 52 Again charging the governor with irresponsible laxity towards the upholding of social distinctions, they insisted that

an act of Connivance of that nature can only be of dangerous consequence, and must give the Negroes reason to set free their natural penchant towards evildoing even further. And so it is in this case […] since aforementioned slave has later told [Sluyter] in public on the street: “Scoundrel, what good did your complaints do you? I will beat you with a stick, etc.”Footnote 53

The idea that the greatest danger of blurring class distinctions among the white population was to set free the forces of slave rebellion was widely shared on all sides of the conflict. During a meeting in Amsterdam, a supporter of Mauricius in the Society of Suriname emphasized that if the conflicts in the colony had been between Europeans alone, it would have been easy for the authorities to come to a settlement. The real threat from the planter opposition arose from the fact that the forty social upstarts who put their signature under the protest could mobilize a force of ten to twelve thousand slaves. To make sure this never happened, it was imperative to prevent “turbulent spirits” from entering the Suriname planter class. The oppositionists again presented their own variant of this argument. Not their demands, but the tyrannical actions and lack of respect shown by Mauricius for his council would lead the slaves to lose the necessary reverence for their masters, threatening “a general massacre of all the Europeans”.Footnote 54 Thus, the invocation of largely imaginary class differences among the white planters became firmly attached to the question of the stability of the fundamental dividing line underlying colonial social order: that between African slaves and white masters.

FORCES OF REPRESSION, SOURCES OF REBELLION

The rulers’ fears became all the more urgent since one of the key questions over which politics split in these years was how to deal with the rapid growth of actual slave resistance in the form of mass marronage and “slave conspiracies”. For both parties, maintaining the slave-based social order was their primary concern. But whether this would be done best by increasing the planters’ power on the plantation, or by strengthening the central institutions of state power based in Paramaribo became an issue that divided the colonial state up to the highest echelons. Fort Zeelandia, in the shadow of which the citizens danced and the slaves laughed on 3 October 1750, was a focal point for these conflicts.

Practically from the start, colonial authorities had deemed the presence of a sufficient number of white labourers and supervisors on the plantation as the first line of defence against slave resistance. It is important to remind oneself that making white or European labour synonymous with supervision constituted an element of racialization, in the same way that equating the word “negro” with “slave” did.Footnote 55 A string of new rules to solidify this division accompanied the transfer of control over the colony from Zeeland to the Society of Suriname in 1683. On 24 January 1684, the governor ordered owners to hand over lists that specified the number of white servants and the number of slaves on their plantations, prescribing that all plantations should have one white person as overseer for ten slaves.Footnote 56 While frequently repeated during the eighteenth century, the intended ratio of white servants to slaves proved to be wildly unrealistic. Lists handed over by the citizens’ captains for 1740 mention the presence of 87 whites and 3,910 slaves on the plantations in the Thorarica region, and 79 whites and 1,872 slaves in Jodensavanne. These examples were representative for the entire period and for plantations throughout Suriname.Footnote 57 Furthermore, while notoriously cruel towards the slaves, the white overseers especially were far from being a disciplined force. They mostly came from poor sections of the European population, under some of the worst conditions of employment available for colonial white labour. Table 1, based on a sample of almost 600 contracts of recruitment for eighteenth-century Suriname in the Amsterdam notarial archives, shows white overseers at the bottom of the hierarchy of white labour in terms of wages and length of obligatory contracts. Of the main groups of white labourers in the colony, with their wage of ninety guilders a year only soldiers earned less.Footnote 58 Soldiers and sailors were sometimes recruited to serve as overseers, but their record of alcoholism and physical and sexual abuse was so infamous that an important manual for plantation managers from the late eighteenth century suggested that the chances of slave unrest would decrease by employing fewer of these guards.Footnote 59 To strengthen the numbers and quality of their white personnel, plantation owners also tried to recruit skilled labourers such as carpenters, coopers, or barber-surgeons. However, as their average salaries and the frequent clauses for additional earnings indicate, the presence of these skilled labourers on the plantation was often only transitory, with many intending to set up shop for themselves as soon as the opportunity arose.Footnote 60

Table 1. Employment contracts for West Indies in the Amsterdam notarial archives, eighteenth century.

Source: The sample of contracts is compiled from Simon Hart's inventory of Amsterdam notarial records, Stadsarchief Amsterdam (SA), Notariële Archieven, collectie S. Hart, nos 433–434.

* Between brackets: number of contracts that provided for a wage increase between the start and the end of the term.

** In practice, writers (schrijvers) often also acted as overseers. However, on average, contracting terms for those signified as writers were substantially better than for those hired as overseers, and closer to those hired as clerks.

Given the clear deficiencies of this small and divided white workforce as a barrier to slave rebellion, successive governors sought to create an apparatus of repression separate from the plantations. This included strengthening the army, fortresses, and guard posts, requisitioning citizens and slaves for patrol duties and hunts for maroons, and shifting some of the prerogatives in relation to punishing slaves from the individual planters to their collective representatives in Paramaribo.Footnote 61 However, planters frequently opposed this buttressing of the colonial state. They insisted that instead of creating security it destabilized the self-contained order of the plantation. In April 1744, the citizens’ captain Pieter van Baerle from Cottica wrote a request defending masters in his precinct, who preferred to organize their own hunts for runaways, rather than employ government patrols. Van Baerle would later become fiscal council, the Paramaribo official responsible for punishing slaves brought to Fort Zeelandia. But as citizens’ captain, he argued that the masters were right to hand out pardons on their own authority to recaptured runaways, and to refuse to bring slaves to the fortress.Footnote 62 A year later, another planter defended evading the obligation to bring captured runaways to Paramaribo by lugubriously claiming that “nothing else but their heads” had returned from the hunt.Footnote 63 The planters’ allegation that the need to send slaves to Paramaribo for punishment could actually stimulate resistance finds some confirmation in a defiant saying used by slaves: “Tangi vo spansi boko mi bin si foto” – Thanks to the Spanish Bock I have seen the town.Footnote 64 In addition, for many slaves, to be sent on a forest patrol provided the ultimate opportunity to join the maroons.Footnote 65 Planters therefore often did not comply with a summons for patrol duty.

Plantation owners and directors raised similar complaints against the requirement to hire out slaves for building and maintaining the fortresses near the city. Like the obligation to supply slaves for patrols, in the eyes of the planters this weakened the workforce on the plantations. Furthermore, planters complained that they did not have enough white servants to guard their slaves on the way to and from Paramaribo, increasing rather than preventing possibilities of marronage. At the fortress itself, black supervisors frequently allowed slaves some time to go hunting and fishing to earn some money on the urban markets.Footnote 66 Finally, Mauricius himself affirmed the complaint by the masters that working at the fortress brought slaves into contact with slaves from other regions, which tended to make them more rebellious and allowed them to learn new means of resistance, such as the use of poison.Footnote 67 In part, the protests by the masters might have been a strategy in negotiating rent prices for their slaves. Before the arrival of Mauricius, they had managed to set a rate of twenty-four stuivers a day, twice the ordinary price for hiring a slave in Suriname.Footnote 68 In comparison, in 1745 free day labourers at the fortress succeeded in obtaining a wage raise from six to twelve stuivers a day, and soldiers protested their employment at this twelve-stuiver rate.Footnote 69 The first conflict between the planters and Mauricius resulted from the latter's attempts to renegotiate the rate at which planters rented out slaves for work at the fortress.

The disputes over responsibilities in supplying the forces and building the infrastructure of colonial power were certainly not theoretical. The numerical weakness and divided nature of white society, combined with the geographical conditions of Suriname, provided the opportunity to build one of the more successful examples of resistance through mass marronage in Caribbean history. In total, Mauricius estimated the number of maroons living in independent communities surrounding the plantations or deeper inland at 3,000. By 1749, their combined strength had become so great that Mauricius was compelled to conclude a temporary peace with the maroons in Upper Saramacca. This peace was heavily contested by planters, who felt that any sign of compromise would encourage other slaves to follow the example of the “bush-negroes”.Footnote 70 In turn, Mauricius insisted that it was the arbitrariness of repression on the plantations combined with the lack of central forces to fight the maroons that put the colony in acute danger. Both sides found proof for their position in the uprising on the plantation of Armand Thomas that broke out on the evening of 21 February 1750. Only two days before, to suppress rumours caused by the peace treaty, the government council had ordered a stern warning to be read out on all the plantations that every slave who tried to join the maroons in Upper Saramacca would suffer beheading. Furthermore, the order emphasized that the peace treaty did not include any of the other maroon communities. Those “would be persecuted by fire and the sword with the utmost rigour”.Footnote 71 However, it is an open question whether this announcement helped to suppress attempts at mass marooning or provided a final push.

The course of the rebellion on the plantation of Armand Thomas, which was the largest uprising on a plantation in the entire period in Suriname, and the brutal repression that followed, has been well described in the literature.Footnote 72 On the evening of 21 February, Thomas, whom we have already encountered as a citizens’ captain and one of the leaders of the opposition to Mauricius, was beaten to death with a hammer by a group of slaves. His scribe, the only other white person on the plantation, soon followed his fate. The lifeless body of Thomas was severely beaten, and his whip was put in his mouth under shouts of “now eat it”, signifying that Thomas's reign of terror on the plantation was one of the prime reasons for the revolt. The rebels then took about thirty guns and tried to mobilize slaves on surrounding plantations. They were captured, and a long series of severe interrogations and torture started. The trial itself again revealed the divisions within the planter state. Mauricius blamed Thomas's arbitrary and violent rule on the plantation and his licentious sexual behaviour, including that towards an Indian slave called Eva, who, after the revolt, gave birth to Thomas's son, for causing the rebellion. As a result, he favoured a combination of exemplary death penalties for the leaders of the revolt and pardons for others. Members of his council insisted that the peace with the maroons in Upper Saramacca had inspired Thomas's slaves to rebel. They blamed Mauricius for undermining the authority of the planters on their own plantation. To restore their authority, they demanded the most brutal punishment for every slave involved. Showing the weakness of Mauricius's position in the council, they got their wish. At least thirty-four participants in the rebellion were sentenced to gruesome deaths.Footnote 73

MAINTAINING A CURFEW SOCIETY

The uprising on the plantation of Armand Thomas preceded the central event in this article by eight months. While these were moments of contention of completely different magnitude and consequence, they are not entirely unconnected. In the wake of the partial peace with the Saramacca maroons and the uprising on Thomas's plantation, fears of conspiracies were running wild. These were not confined to slaves on the plantations nearer to the maroon villages; they were raised, too, against slaves who lived and worked in and around Paramaribo, as well as against members of the free population suspected of collaborating with them.

A particularly interesting case that highlights the importance of slave mobility and the diversity of contacts between free and unfree persons was the charge brought against Askaan and April. Both were owned by the “separated wife of Johan van Hertsberg”, Willemina Schroder. Their captors found six guns with April belonging partly to him and partly to Askaan, and the prosecutor stated that these were intended for “fighting against the whites, or making attempts at rebellion”.Footnote 74 Even under torture, the two captives maintained that they planned to use the guns only for hunting.Footnote 75 However, they did reveal an interesting network of contacts through which they had acquired these arms. Askaan said that April had bought one gun from Sockelaet (or Chocolate), who was a slave at the almshouse, received two from the free black man Adoe, bought or hired one other for eight shillings, and had bought two older guns from the “Jew negro” Agouba or Prins, who lived on the Waterkant. The “negress Europa, who used to belong to the ensign Meijer”, had supplied a calabash of gunpowder. In addition, an earlier interrogation had led to the conclusion that gunpowder and bullets had been bought from an “Indian”. During his trial, his interrogators asked Askaan whether he was not aware “that one white person has enough courage to take aim at a hundred slaves”.Footnote 76 However, when push came to shove his persecutors preferred not to take the risk. Despite his insistence under torture that he had not planned to use the guns against his masters, on 5 June 1750 Askaan was sentenced “to the cord”, his head to be put on a stake, and his “cadaver to be burnt to ashes”.Footnote 77 Similar attitudes were shown in a simple case of marronage that occurred around that time. Quater Cheureua from the plantation of Jacques de Crepij near Paramaribo was brought to Fort Zeelandia accused of wanting to join a village of runaways. To the “very pernicious design to desert”, the authorities added the charge of conspiracy. Quater was sentenced to be brought to the execution terrain, where he was bound on a cross, his bones broken “from the bottom upwards”, and beheaded. His lifeless body was then subjected to the same ritual disfiguring as Askaan's.Footnote 78

Next to the mounting slave resistance, the internal division of the white community and the apparent weakness of the apparatus of repression, authorities considered the mobility of slaves and the poor, whether black, mestizo, or white, to be one of the greatest potential dangers to social order. A crucial tool for the regulation of colonial society was an intricate web of curfews and passports restricting the movement of different groups among the lower classes. The breaking of such curfews by slaves who remained on the square before the governor's house after sunset, and by a soldier who did not return to his barracks after nine in the evening, played an important role in Mauricius's description of the “disreputable dance” of early October 1750. This was a direct reflection of the importance attached to upholding curfews in Suriname everyday life. Of course, the idea that controlling the movement of working people and the poor was imperative to maintaining order was nothing new. Especially in the dire persecution of beggars and the restrictions imposed on itinerant day labourers not attached to a master or guild, European states and town governments had long experience in regulating who could be where to do what, and under what conditions.Footnote 79 Frequently, such practices arose simultaneously from fear of rebellion and more immediate concerns about property and theft. Similar motivations existed in the imposition of a regime of curfews in colonial contexts.Footnote 80 However, the more limited reach of authority, the semi-militarized conditions and legal structures under which the lower classes were forced to operate, and the presence of large indigenous and enslaved populations greatly amplified their use.

Already in 1669 and 1670, just a few years after the Dutch takeover of Suriname, ordinances were published admonishing plantation owners to control the movement of their slaves more strictly by allowing them to move off the plantations only with passports, within set times, and for clearly delineated purposes.Footnote 81 Attempts to limit the unsupervised movement of slaves conspicuously mixed with concerns about tying wage labourers to a single place of employment. Significantly, these first regulations already entailed divisions between black and white labourers that went beyond the simple substitution of the word negro for slave. A separate clause in the March 1670 labour regulation addressed the status of manumitted Africans, saying:

That all negros that have received their liberty from their masters, will be obligated to hire themselves out to one master or another, on penalty of being severely whipped every time of being found without employment or being in someone's service.Footnote 82

Fears that uncontrolled movement or a life outside employment for free and unfree blacks would create openings for smuggling and the sale of stolen goods provided the initial thrust for such racialized legislation. A 1679 ordinance prohibited “any boats without white people on board” from travelling on rivers or creeks without express permission of plantation owners, alleging that “several boats with negroes […] go up and down the river to ravage here and there”. If the black passengers of such a boat without whites failed to show their passes at first call, their vessel should be shot at “as if at public enemies, because for the service of the land and the preservation of the colony, they should be viewed as such”.Footnote 83 Another prohibition to trade goods with slaves in June 1684 and a similar one against trading with slaves or soldiers in May the next year followed this.Footnote 84 Perhaps the most striking rule, effectively introducing an early form of racial profiling, allowed sentries to shoot on sight any black person on the streets later than half an hour after sundown “as if they were runaways”. As a justification, the regulation explained that this was necessary “because at night one cannot tell the good from the bad negroes, since one cannot tell the difference from their cloths”.Footnote 85

In the heated atmosphere of the late 1740s, maintaining slave curfews became a particularly important element in enforcing public order. To assist in this task, the government council decided on 5 September 1747 to install a clock in the tower of Fort Zeelandia.Footnote 86 Even a full century later, a traveller in Suriname noticed that every day at eight o'clock in the evening a cannon would be fired from the fortress, which contained the only public clock in Paramaribo, to mark the moment when slaves should be indoors.Footnote 87 In the summer of 1749, new rules followed prescribing that slaves could be on the streets of Paramaribo at night only if carrying a lantern, and that the citizens’ guard should start making its rounds at seven in the evening.Footnote 88 However, given the prevailing tensions among white citizens the mode of operation of these citizens’ guards created its own problems. On 4 December 1749, the government council discussed at length the disorders created by citizens, who randomly opened fire on slaves who merely sat on the pavement outside their masters’ houses, or were walking the streets in the presence of their masters “so that shots of hail flew around and through the company”. Apparently, several of the inhabitants of Paramaribo had already been shot in such altercations. When the NCO Bulke, who was responsible for opening fire, was questioned by his lieutenant, he had answered: “We want to shoot at slaves, and if not, you should dissolve the citizens’ guard”.Footnote 89 Based on this testimony, the council considered only the possibility that shootings at night were a form of protest against guard duty. However, Bulke's answer also suggests how easily policing the street could slip into vigilante actions against the slaves.

A safer, less contentious way of maintaining order on the street was to try to close down venues for unguarded activity after hours, especially where such venues provided a space for interaction between slaves and free whites and blacks. Many rules and regulations were aimed at enforcing separation, especially in the context of travelling back and forth to Paramaribo. Among the most notorious were the draconian mutilations introduced as punishment for black and Indian slaves found drinking and playing games with white people in taverns (1698), and punishment by death for any “negro” having sexual relations with a white woman (1711).Footnote 90 Curfews on soldiers and sailors also helped to limit interaction. This included the rule that, after the evening call, soldiers should remain confined in their barracks on pain of running the gauntlet.Footnote 91 However, in such attempts the authorities were up against what was perhaps the most powerful enemy of the curfew and of social segregation in general in the port city: the underground bar. In early February 1750, the court in Paramaribo sentenced the German immigrant Christiaan Crewitz for inviting “several Negroes into his house, where sitting at his Table, he served them beer and soup”, as well as selling alcohol to several others.Footnote 92 One of the most interesting elements of the case is that Crewitz, who declared that before opening a small bar he had made a living by “catching tortoises with the Indians in the river Marrewyne”, repeatedly professed that he did not believe he had done anything wrong by serving drinks to black men.Footnote 93 Crewitz was condemned to pay a fine of 500 guilders, the equivalent of between two and four years’ salary for an unskilled worker in Suriname, and was banished from the colony for life.Footnote 94

The trigger-happy NCO Bulke and Crewitz can be seen as presenting opposite ends of white society in Paramaribo. However, these opposites might not always have been as far apart as they seem. Their everyday context brought lower-class whites into continuous contact with the enslaved, sometimes as overseers, sometimes as colleagues, buyers and sellers, gamblers or drunks. This could be the basis for reflections on shared miseries, as well as for the exploitation of their whiteness as a protective shield against the masters. The two attitudes could even exist side by side. John Gabriel Stedman described the working conditions of many common sailors:

In every part of the colony they are no better treated, but, like horses, they must (having unloaded the vessels) drag the commodities to the distant storehouses, being bathed in sweat, and bullied, with bad language, sometimes with blows; […] The planters even employ those men to paint their houses, clean their sash windows, and do numberless other menial services, for which a seaman was never intended. All this is done to save the work of their negroes, while by this usage thousands are swept to the grave, who in the line of their profession alone might have lived for many years; […] I have heard a sailor fervently wish he had been born a negro, and beg to be employed amongst them in cultivating a coffee plantation.Footnote 95

As an answer to real or perceived social degradation, many embraced cruel displays of racial superiority, as did the sailor who, in passing, “broke the head of a negro with a bludgeon, for not having saluted him with his hat”.Footnote 96 In this case, as in Bulke's, racist attitudes among the white population became a powerful instrument for maintaining the curfew society.

COLONIAL ROUGH MUSIC

The previous sections have examined how the physical surroundings, the context of political tension within the planter class and slave resistance, and the importance of curfews for the maintenance of racialized social order all provide elements for understanding the contentious nature of Johanna Catharina Brouwer's dance. This final brief section will look at the significance of the most carnivalesque aspect of the confrontation that took place on the night of 3 October 1750: rough music, both in its literal and its symbolic sense represented by the trumpeter playing “the most infamous sound in the world, while wenches, children, and slaves loudly laughed and shouted”. Music and dance played a crucial role in Suriname slave life. It provided not only one of the rare instances for truly independent social interaction, but also a vehicle for passing on secret messages undetectable to the ear of the masters, concealed in song, rhythm, or dance movements.Footnote 97 From the other side, a vehement dislike of African song and dance was one of the important cultural markers of the distance between civilized (white) society and the world of the slaves. In his nineteenth-century travelogue, Gaspard van Breugel attested to his understanding of the importance of this marker by inserting the following description of a banja, a slave dance:

To unite their voices with their instruments, one sees the so-called musicians seated on the ground in a row; hitting their also so-called instruments, twisting their bodies and nodding their heads, while drawing faces with which one could immediately scare the naughtiest children to bed […] Behind them stands a crowd that shouts, more than sings, in such a way that one needs a bale of cotton to plug one's ears not to hear that beautiful music.Footnote 98

Well aware of the power of music as an instrument to mock the white masters, or worse, colonial authorities throughout the period of slavery waged an uphill battle to prevent the slaves from singing, playing the drums, and dancing. Funerals in particular became moments of contention.Footnote 99 On 6 February 1750, the government council discussed the “frequent assembly of slaves [in Paramaribo – PB] for funerals”. The immediate cause of this discussion was the funeral of one of the slaves of S. Clijn. A large crowd had gathered in front of his house, “making much noise and rumour, creating confusion and murmurs”.Footnote 100 The council reconvened to discuss concrete measures on 26 February, a few days after the news of the uprising on the plantation of Armand Thomas had reached Paramaribo. In this session, the council decided to allow masters who owned houses or gardens outside the city to bury their slaves there instead of in the town's slave graveyard. For slave funerals that did take place in Paramaribo, the bailiff was ordered to make sure that no “noise” accompanied the ceremony. Masters who allowed any form of baljaaren (dancing) during a funeral would be fined 500 guilders. Slaves arrested during a funeral for contravening this order would receive the Spanish Bock.Footnote 101

Was Mauricius's remark on the quality of the trumpet playing at the party of Johanna Catharina Brouwer an allusion to yet another barrier of social order and racial distinction being crossed? This will have to remain a speculation. However, it is interesting to note that almost all reports on neighbourhood brawls in Suriname in this period mention noise and loud music as major affronts to public decency. On 20 November 1748, Pieter Brouwer returned from his plantation to his house in Paramaribo to nurse his sick wife. The next evening, at around nine-thirty, a loud party began in the house of his neighbour Dirk Brendt. Musicians played the violin and blew horns, “accompanied by continuous shouts of Hurrays and other noise”. Brouwer alleges that Brendt was too drunk to pay a visit to his house and complain, so that the party continued until half an hour before midnight. However, the next morning the party resumed. What most upset Brouwer was that, “probably to increase the noise”, to the horns was now added “the sound of a drum, again accompanied by continuous shouts of Hurray, at which hundreds of black boys gathered in front of the door”. This was the final straw that led Brouwer to complain about his neighbour's behaviour, but Brendt did not take this well. Instead, he came to Brouwer's door to shout: “Canaille, did you have the heart to complain about me to the Fiscal, I will goddamned tear you to pieces.” Fighting ensued, and ended only when soldiers came to take Brendt to the fortress.Footnote 102 In this 1748 case, the actual overstepping of the proper time for celebration and dancing, playing noisy music, and involving slaves in a public spectacle figured in ways very similar to the descriptions encountered in Mauricius's October 1750 complaint to underline a breakdown in public order.

References to slave dances or baljaaren could also be employed to hint at even greater digressions, connected to both gendered and racialized distinctions. This is revealed by an explosive brawl that took place just a few years earlier in the Gravestraat or Soldiers’ Street, which ran between the central square and the gardens on the outskirts of Paramaribo. In the late afternoon of 22 October 1745, violence erupted between Moses Levy Ximenes and David and Rachel Moateb, a mulatto. The root of the fight was that earlier, David and Rachel had visited Moses's father to complain about the noise emanating from his house. The old Ximenes had had a loud argument with one of his enslaved female servants. According to Rachel, Moses’ father had responded to the complaint by “calling her husband a mulatto”. Despite the fact that she herself was of mixed descent, she took this as a grave insult since her husband “was a legitimate white man” like Moses's father.Footnote 103 According to Moses, the real insult had been David and Rachel's interference with a domestic affair, since it was his father's right “to chastise [kastijden] his negroes with words”.Footnote 104 Between the two parties, testimonies differed over the question of who at this point was the first to resort to physical violence. However, one other small difference between the statements given in this case matters more for the current purpose. One of the neighbours gave testimony to support Moses's plea. In this statement, rather than talking about his father's chastising of his slaves, Moses was presented as saying: “What do you have to do with the quarrel [ruzie] of my father, as he danced [baljaerden] with his slaves.”Footnote 105 The word baljaeren in this context is so strange that one cannot help suspecting an unspoken meaning, pertaining to violence, sex, or both. In any case, it helps to underline a point that is crucial for understanding what happened on the night of 3 October 1750. When involving masters and slaves, a dance was never just a dance.

CONCLUSIONS

Starting from an incident in colonial Paramaribo in the autumn of 1750 in which, according to the Dutch governor Mauricius, many of the proper barriers separating rich and poor, men and women, adults and children, white citizens and black slaves were crossed, this article has traced the complexities of everyday social control in colonial Suriname. The rowdy ball for the birthday of Johanna Catharina Brouwer's daughter, which drew the governor's ire, can easily be understood as a minor skirmish in the long-lasting conflict between the increasingly confident colonial planter class in Suriname and the local representatives of Dutch company rule. In the middle of the eighteenth century, such conflicts occurred throughout the Atlantic world as a result of the rapid rise of a Creole colonial elite, which self-confidently asserted its role in expanding capitalist networks across European empires. However, as so often in the history of popular rebellion, divisions within the ruling class also brought to the fore deeper fissures between the political and economic elites on the one hand and the lower classes on the other. Through the prism of the different transgressions mentioned by Mauricius in his report and letters about the “disreputable dance”, we can observe essential characteristics of repression and rebellion in mid-eighteenth-century Suriname. In particular, it can be shown how instruments of social segregation with a long pedigree – enforcing distinctions of class and status, invoking taboos to limit the free interaction between men and women and adults and children, restricting the movement of labourers and the poor through passports and curfews – intersected with the harsh racialized separations of an eighteenth-century Atlantic slave society.

Much of the literature on the relationship between slavery and race focuses on the plantation as race-making institution and the planter class as the immediate progenitors of racial capitalism. Studies of urban slavery on the other hand have emphasized the greater scope for social contact between blacks, mestizos, and whites of various social status in the bustling port cities of the Atlantic. This article has attempted to understand practices of racialization and control in the port city of Paramaribo, not by contrasting the city with its plantation environment but by underlining the connections between the two social settings that together shaped colonial geography. Continuous movement between plantation and port, including the unsupervised movement of slaves, was a crucial aspect of the political economy and the cultural life of a society like Suriname. The article has focused on everyday activities in Paramaribo (dancing, working, drinking, arguing) that reveal the extent of contact between slaves and non-slaves. The imposition of racialized forms of repression that set one group against the other, frequently understood primarily as a means to justify the apparent stasis of the plantation system with its rigid internal divisions, in practice functioned precisely to fight the pernicious effects of mobility in mixed social contexts. In the process, plantation owners and the state that they at least in part controlled could sometimes find themselves at loggerheads, but, ultimately, they found themselves united in their primordial fear – that of slave rebellion.

One charge that could be made against this article is that the impact of mobility has not been researched through systematic quantification. Instead, it has illuminated key aspects of social relations in colonial Paramaribo through discursive practices at a moment of widespread contention. The new social historians of the 1970s employed this method to reveal the importance of rituals, culture, and perceptions of justice at a time when their colleagues were mostly concerned with hard material factors. This article has in a way tried to retrace their steps. Starting from cultural practices and real and imagined distinctions of status, gender, age, and race surrounding an apparently innocuous birthday party, it has sought a way back to the brutal realities of colonial control in which these imaginings obtained their violent urgency.