Abstract

Objectives

Low sexual desire is a common complaint among women in the reproductive years. There is controversy regarding the relationship between testosterone (T) and female desire, but there is also lack of research on moderators. Lack of awareness of effects of T on emotions and bodily sensations might interfere with the subjective experience of desire. Moreover, T appears to be more important for searching and competing for partners than for long-term pair bonding. Therefore, we examined if interoception, alexithymia, maladaptive psychological defenses, and relationship status, moderated the relationship between salivary T and female desire.

Methods

One hundred sixty eight Portuguese women of reproductive age completed the desire dimension of the Female Sexual Function Index, the Toronto Alexithymia Scale (TAS-20), and the Defense Style Questionnaire (DSQ-40). Interoception was determined by a heartbeat detection task. Participants reported if they had a regular sexual partner. Luminescence immunoassays were used to determine salivary T.

Results

Three multiple regressions models revealed that, among unpartnered women, higher desire was predicted by the combinations of 1) higher T and lesser alexithymia, 2) higher T and less use of maladaptive defenses, 3) higher T and greater interoception. For partnered women, neither T nor the interactions of T with indices of emotional and bodily awareness predicted desire.

Conclusions

These findings provide preliminary evidence that T is more important for the desire of unpartnered women, and that lack of conscious awareness of emotions and bodily sensations interferes with the effects of T on the subjective experience of desire.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Low sexual desire is a common complaint in women in their reproductive years (Fallon 2008; Stuckey 2008), and it has a complex etiology (Apostolou 2016). Off-label testosterone (T) therapy is sometimes used for treating low desire in women (Fallon 2008; Stuckey 2008; Woodis et al. 2012), but the link between T and female desire remains controversial. This raises the possibility of psychosocial factors moderating the relationship between T and female desire.

Research has shown that women’s free T or salivary T is related to higher sexual desire (Alexander and Sherwin 1993; Costa et al. 2016a; Guay and Jacobson 2002; Guay et al. 2004; Riley and Riley 2000; Turna et al. 2005; Wahlin-Jacobsen et al. 2015). Salivary T has been considered to reflect free T, although recent research with equilibrium dialysis showed that the proportion of free T in women’s saliva may reflect serum free T less than expected, because T tends to bind to salivary proteins (Fiers et al. 2014). Total T appears to be less consistently related to female desire (Basson et al. 2010; Santoro et al. 2005; Wahlin-Jacobsen et al. 2015). However, several studies failed to find an association between free or salivary T and female desire (Davis et al. 2005; Jones et al. 2018; Roney and Simmons 2013; van Anders 2012). Also, T therapies for low desire have yielded conflicting findings, especially so in women of reproductive age (Stuckey 2008; Woodis et al. 2012). This raises the possibility that there are moderators of the relationship between T and female desire, but research on such moderators is lacking. This is not to say that T is the main hormonal modulator of female desire; in fact, estradiol and progesterone have been proposed as more relevant for female desire (Cappelletti and Wallen 2016; Roney and Simmons 2013). However, T levels might still have additional sexually motivating effects, if there are no counteracting inhibitory mechanisms. This makes research on moderators of the relationship between T and female desire important.

It is rather likely that higher sexual motivation increases the propensity to be attentive to sexual cues. In both sexes, T was shown to increase attention to sexual cues (Alexander et al. 1997; Alexander and Sherwin 1991, 1993; Poels et al. 2013; van der Made et al. 2009), which argues for a role of T in sexual motivation. In women, T was also shown to be increased after erotic imagery (Costa and Oliveira 2015; Goldey and van Anders 2011; López et al. 2009) and before intercourse (Dabbs Jr and Mohamed 1992; van Anders et al. 2007), further arguing for a role of T in female sexual motivation. However, it has been proposed that, in women with low desire attributed to psychological inhibitions, T does not increase sexual desire, and even diminishes implicit attention to sexual cues (Poels et al. 2013; van der Made et al. 2009). Thus, it is likely that any process that counteracts the putative effect of T on attention to sexual stimuli leads to a decoupling of T from sexual desire. Likely processes that have such counteracting effect are lack of bodily and emotional awareness.

Sexual desire requires activation of brain regions sensitive to T (hypothalamus, amygdala) alongside with regions responsible for bodily and emotional awareness (anterior cingulate cortex, insula), that is, regions that allow the conscious experience of emotional and motivational states (Cacioppo et al. 2012). Thus, it seems likely that if there is a reduced awareness of emotions and bodily sensations, the effects of T on the feeling of sexual desire can be inhibited. Alexithymia is a condition characterized by difficulties identifying and communicating emotions, and in women, it was related to low sexual desire (Madioni and Mammana 2001) and lower intercourse frequency (Brody 2003). Alexithymia was also related to smaller volume of anterior cingulate cortex and anterior insula (Borsci et al. 2009; Goerlich-Dobre et al. 2015). In addition, women’s alexithymia was found to correlate with greater decoupling of T from desire (Costa and Oliveira 2015). Therefore, we expect that the relationship between T and female desire is moderated by alexithymia so that a direct correlation between T and sexual desire is more likely to occur in women with lesser alexithymia, that is, in women more able to be consciously aware of their emotions.

Alexithymia correlates strongly with maladaptive defense mechanisms (Costa and Oliveira 2015; Helmes et al. 2008), which are automatic psychological processes for coping with stressors by ignoring their reality or the emotions they elicit (Costa and Brody 2013). Maladaptive defense mechanisms might be a cause of alexithymia (Helmes et al. 2008; Taylor et al. 2016). They include dissociation, splitting, projection, somatization, denial, and isolation of affect, among others. When used frequently, maladaptive defenses constitute a trait-like style of automatic (involuntary) coping by diminishing emotional awareness. Similarly to alexithymia, greater use of maladaptive defenses was associated with lower sexual desire and lesser personal importance of intercourse (Costa and Brody 2013; Costa and Oliveira 2015; Costa, Oliveira et al. 2016a). In fact, if sexual desire is a stressor via psychological conflict, one should expect a decoupling of subjective desire from T levels, as the sexual motivation modulated by T is put out of conscious awareness by maladaptive defense mechanisms. Previous research confirms this notion: greater decoupling of T from desire explained the association between maladaptive defenses and low desire (Costa and Oliveira 2015). Hence, it is expected that the relationship between T and female desire is moderated by maladaptive defense mechanisms so that a positive correlation between T and sexual desire is more likely in women with lesser use of maladaptive defenses.

Another factor that might contribute to greater decoupling of T from desire is reduced awareness of bodily sensations. Interoception refers to the conscious awareness of internal bodily sensations, and appears to be the basis of emotional awareness (Dunn et al. 2010; Herbert et al. 2011; Strigo and Craig 2016). Therefore, it is likely that greater interoception allows a greater conscious awareness of the hormonal modulation of bodily states that underlie the subjective experience of desire. This notion seems to be strengthened by studies in women showing that increases in interoception caused by mindfulness meditation correlated with increases in desire (Patersen et al. 2017) and reductions in psychological barriers to healthy sexual functioning, such as negative self-judgments and difficulties being focused on present-moment experiences, including emotional and bodily experiences (Silverstein et al. 2011). Furthermore, for women during sexual activity, more intense self-reported body awareness correlated with greater sexual desire (Costa et al. 2016b). Therefore, the association between T and female desire is expected to be moderated by interoception so that a positive correlation between T and female desire is more likely in women with higher interoception. Heartbeat detection accuracy is a commonly used measure of interoception, but concerns have been raised regarding its validity (Murphy et al. 2018). Nevertheless, better performance in heartbeat detection tasks has been related to greater reported intensity of pleasant and unpleasant emotional responses (Barrett et al. 2004; Herbert et al. 2007; Pollatos et al. 2007; Wiens et al. 2000), as well as greater concordance between heart rate and reported intensity of emotional responses (Dunn et al. 2010). This indicates that the conscious awareness of changes in emotional states tends to be greater among those who can detect their heartbeats more easily. Moreover, greater accuracy of heartbeat detection was associated with greater activity of the posterior insula (Schultz 2016), which was shown to be important for both interoception and sexual desire (Cacioppo et al. 2012). This seems consistent with a preliminary study showing that women with greater heartbeat detection accuracy tend to have higher desire (Costa et al. 2018). Therefore, we measured interoception as heartbeat detection accuracy.

Other aspect that has been overlooked in research on the relations between T and desire is relationship status. A body of research has been revealing that men in committed relationships have lower T levels than uncommitted ones (Burnham et al. 2003; Gray et al. 2002, 2004; Hooper et al. 2011; Sakaguchi et al. 2006; van Anders and Goldey 2010; van Anders and Watson 2007). More limited evidence suggests a similar association in women (Costa et al. 2015; Goldey et al. 2018; van Anders and Goldey 2010; van Anders and Watson 2007), but also that this association is moderated in a way that T is not likely to be lower among partnered women with more extraversion, more sensation seeking (Costa et al. 2015), and more interest in casual sex (Edelstein et al. 2011). Also, more satisfying relationships were inversely associated with own and partner’s T (Das and Sawin 2016; Edelstein et al. 2014). This has been interpreted as higher T levels promoting mating effort, that is, searching and competing for partners. In contrast, lower T is thought to favor long-term pair bonding and parental care (Costa et al. 2015; Goldey et al. 2018; van Anders and Goldey 2010). Hence, higher T levels are likely more relevant for the desire of people who search for new partners than for the desire of people in satisfying committed relationships. This notion seems to be strengthened by studies showing that women’s T correlated inversely with frequency of partnered sexual activity (Das and Sawin 2016; van Anders and Goldey 2010) and that committed women’s T was found to be lower only in the case they were sexually active (Goldey et al. 2018). According to these findings, we should expect that T is less relevant for committed women’s desire, and as such it is expected that T does not correlate directly with desire in women with a regular partner, even when there are indicators of good emotional and bodily awareness. Differently, unpartnered women’s desire is expected to correlate with T, but only if there is a better capacity to be consciously aware of emotions and/or internal bodily sensations.

For summarizing the objectives of the present study, we examined the hypotheses that among unpartnered women (but not among partnered ones), higher sexual desire is associated with the interaction of with higher T levels and 1) greater emotional awareness (lesser alexithymia), 2) a more adaptive defense style (less use of maladaptive defense mechanisms), and 3) higher interoception (greater heartbeat detection accuracy).

Method

Participants

Two hundred nine women of reproductive age participated in the study. Exclusion criteria applied to those taking antidepressants (N = 16) and those reporting being bisexual or homosexual (N = 18) for reasons of having a more homogeneous sample. Six did not provide information on oral contraception and in five it was not possible to determine T, which leaves a final sample of 168. Descriptive statistics are depicted in Tables 1 and 2. All participants gave informed consent, and received course credits or a ten-euro voucher. The study was approved by the local Ethics Committee.

Measures

Alexithymia was assessed by the Toronto Alexithymia Scale (TAS-20) (Taylor et al. 2003; Veríssimo 2001). It consists of twenty self-descriptive items scored on a scale from 1 to 5, and has been widely validated as a measure of alexithymia (Lumley et al. 1996; Parker et al. 2003; Taylor et al. 2003, 2016). It has three dimensions: difficulty identifying feelings, difficulty describing feelings, and externally-oriented thinking. Scores range from 20 to 100. Significant alexithymia was established as scores above 60 (Parker et al. 2003).

Maladaptive defense mechanisms were assessed with the immature defenses subscale of the Defense Style Questionnaire (DSQ-40) (Andrews et al. 1993; Blaya et al. 2007), which is composed by self-descriptive 9-point items assessing conscious cognitive and behavioral derivatives of various automatic defense mechanisms (projection, denial, isolation of affect, devaluation, passive-aggressiveness, splitting, dissociation, autistic fantasy, somatization, acting-out, displacement). The total score is obtained by averaging the item scores. Normative values were considered to be 3.54 (± .95) (Andrews et al. 1993). In studies with versions in several languages, this subscale has been associated with psychopathology (Andrews et al. 1993; Blaya et al. 2007), alexithymia (Costa and Oliveira 2015; Helmes et al. 2008), lower sexual desire and lesser importance attributed to intercourse (Brody and Costa 2013; Costa and Oliveira 2015; Costa et al. 2016a).

For measuring interoception, participants were asked to count their heartbeats during three trials of 25, 35, and 45 s, while heart rate was being recorded with an MP150 BIOPAC system running the software Acqknowledge (BIOPAC systems, Inc.). Ag-AgCl electrodes were attached to both wrists and one ankle. Sampling rate was 1000 samples per second. Afterwards, interoception accuracy was calculated by the following formula: one minus the average absolute value of the counted heartbeats subtracted from the recorded heartbeats, divided by the latter (Dunn et al. 2010).

Sexual desire was assessed with the desire domain of the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) (Rosen et al. 2000). It consists of two items assessing frequency and intensity of female desire or interest over the past four weeks on a 5-point scale. This is a widely used measure of sexual desire with sensitivity to detect hypoactive sexual desire disorder (Gerstenberger et al. 2010; Witting et al. 2008).

Hormonal Assays

Salivary T was assessed with luminescence immunoassay kits from IBL-International (RE62031). Participants provided approximately 1 ml of saliva. The saliva samples were collected into a polypropylene tube and conserved at −20°. Later, they were centrifuged for 10 min at 2245 g. Inter-assay and intra-assay coefficients were 7.17 and 2.28%. All saliva samples were collected between 14 h00 and 18 h00, because T collected in the afternoon is more robustly related to cognitive and behavioral variables (Gray et al. 2004; Roney et al. 2007).

Statistical Analyses

We performed three backward multiple regressions with sexual desire as dependent variable, separately for partnered and unpartnered women. Regarding the independent variables, the first regression included T, alexithymia (inverted score), their interaction term, and oral contraception, which is known to lower T (Zimmerman et al. 2013). The second regression included T, maladaptive defenses (inverted score), their interaction term, and oral contraception. The third regression included T, interoception, their interaction term, and oral contraception. In order to calculate the interaction terms, the values of T and the scores of alexithymia, defense mechanisms, and interoception, were standardized. Additionally, the alexithymia and maladaptive defenses scores were inverted. This is because we predict that higher sexual desire is related to the interactions of 1) higher T levels and higher emotional awareness (lesser alexithymia), and of 2) higher T levels and a more adaptive style of psychological defenses (less use of maladaptive defenses). Oral contraception was deviation coded as −.5 (not taking oral contraception) and .5 (taking oral contraception).

In order to interpret the moderations hypothesized to result from the multiple regressions, we plotted two-way interactions with moderators having high and low values defined as above the 66th percentile and below the 33th percentile, respectively.

Results

Alexithymia and maladaptive defenses correlated strongly with each other (r = .55, p < .001). Interoception did not correlate with maladaptive defenses (r = .06, p = .444) nor with alexithymia (r = −.001, p = .985). Higher interoception correlated with slower heart rate (r = −.22, p = .006). Interoception was found to be greater when the trials of heartbeat detection were longer. In paired samples t-tests, mean accuracy in the 25 s interval trial of heartbeat detection (40%, SD = 25) was lesser than in the 35 s trial (43%, SD = .22) and in the 45 s trial (45%, SD = 22), t = 2.83, p = .005, and t = 4.29, p < .001, respectively. The difference between the 35 s trial and the 45 s trial was marginal, t = 1.85, p = .065.

As shown in Table 3, T was uncorrelated with desire for the total sample. This was also the case of the subgroups of unpartnered (r = .21, p = .102) and partnered women (r = .002, p = .982). In partial correlations controlling for oral contraception, T was still uncorrelated with desire in unpartnered (r = .23, p = .076) and partnered women (r = .02, p = .883). As can be seen in Table 3, higher desire correlated with higher interoception, lesser alexithymia, and less use of maladaptive defense mechanisms.

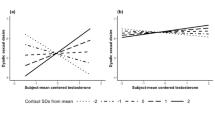

As displayed in Table 4, unpartnered women’s desire was predicted by both greater emotional awareness (lesser alexithymia, marginally) and the interaction between emotional awareness and T. As shown in Fig. 1, higher desire occurs with higher T levels and greater emotional awareness. The correlation between desire and the interaction of T and emotional awareness was greater for the unpartnered women than for the partnered women (Z = 2.47, p = .014). Partnered women’s desire was only predicted by greater emotional awareness (see Table 4).

As depicted in Table 4, unpartnered women’s desire was predicted by both a more adaptive defense style (less use of maladaptive defenses) and the interaction between a more adaptive defense style and T. As presented in Fig. 2, higher desire takes place with higher T levels and a more adaptive defense style. The correlation between desire and the interaction of T and an adaptive defense style was greater for the unpartnered women than for the partnered women (Z = 1.92, p = .055). For the partnered women, desire was only predicted by a more adaptive defense style (see Table 4).

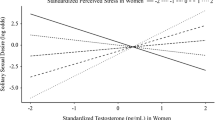

As can be seen in Table 4, unpartnered women’s desire was predicted by the interaction between interoception and T. As presented in Fig. 3, higher desire happens with higher T levels and greater interoception. The correlation between desire and the interaction of T and interoception was greater for the unpartnered women than for the partnered women (Z = 2.02, p = .043).

Because interoception correlated inversely with heart rate, we included heart rate as an additional predictor in the multiple regressions, but the results were not meaningfully changed; desire was solely predicted by the interaction between T and interoception (β = .31, p = .020).

Figure 4 shows three-dimensional scatters plots between desire, T, and a) alexithymia, b) maladaptive defenses, and c) interoception.

Discussion

Several studies show positive relations of sexual desire with free and salivary T in women of reproductive age, but this link has been challenged by others. This raises the possibility of moderators influencing the relationship between T and female desire, and thereby contributing to the several null findings. The present study confirmed this possibility. We found that, in simple correlations, salivary T was unrelated to desire. However, in multiple regressions, we found that, among unpartnered women, higher desire was predicted by the interaction of higher T levels and greater emotional or bodily awareness, as indexed by lesser alexithymia, less use of maladaptive defense mechanisms, and greater interoception (heartbeat detection accuracy). These associations did not occur for the subgroup of partnered women. These findings suggest that salivary T and female desire correlate positively in unpartnered women with indicators of better emotional or bodily awareness, which is consistent with a previous study showing that alexithymia and maladaptive defense mechanisms correlated with greater discordance between T and female desire (Costa and Oliveira 2015).

We did find a correlation between the heartbeat detection accuracy and sexual desire, which is consistent with other research on desire and interoception (Costa et al. 2018; Patersen et al. 2017). Given the concerns about to what extent heartbeat detection accuracy measures general interoception (Murphy et al. 2018), perhaps cardiac awareness, cardioceptive attentiveness or cardioception (Herbert et al. 2010; Schultz 2016) are better (more specific) terms. Some studies have also related greater alexithymia to lower interoception, as indicated by the heartbeat detection task (Herbert et al. 2011; Murphy et al. 2018), but we did not replicate those findings, perhaps because of the confounds that likely play a role in it (Murphy et al. 2018).

According to the dual model of sexual functioning, low desire may arise from an overactive inhibitory system and/or a hypoactive excitatory system. It is likely that, by its action on hypothalamus and limbic system, T has an excitatory role that can be counteracted by inhibitory forces that reflect on lack of awareness of emotions and bodily sensations. Therefore, our findings seem congruent with experimental research revealing that in women with low desire attributed to psychological inhibitions, pharmacological treatments with T combined with phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors were ineffective in increasing attention to sexual cues and sexual desire (Poels et al. 2013; van der Made et al. 2009). In contrast, T combined with phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors increased desire and attention to sexual cues in women with low desire not attributed to psychological inhibitions, but rather to an impaired excitatory system (Poels et al. 2013; van der Made et al. 2009). Our findings also seem congruent with Freud’s views that defense mechanisms can put libido out of consciousness with adverse effects on sexuality (Freud 1908/1953).

In addition, our findings corroborate the notion that T is more important for the desire of unpartnered women, as long as there is good emotional and bodily awareness. Sexual desire of partnered and unpartnered people may differ physiologically and behaviorally in important ways with the desire of unpartnered women being more dependent on T for motivating efforts to search and compete for partners. Indeed, T has been shown to be related to competitive behavior and increased risk-taking in women (Casto and Edwards 2016; Oliveira and Oliveira 2014), which are more important to be connected with the sexual motivation of unpartnered people. However, it should be noted that T might not be lower among committed people with certain personality characteristics, such as extraversion, sensation seeking (Costa et al. 2015) and interest in casual sex (Edelstein et al. 2011). This raises the possibility that T might have a more important role in the desire of committed women with these personality traits. Future research is needed to clarify these issues.

In the two referred experimental studies showing positive effects of T on desire among women whose etiology was attributed to hypoactive excitatory mechanisms (Poels et al. 2013; van der Made et al. 2009), it is not clear how many women were committed. However, in these experiments, T administration was sublingual, which caused a phasic increase in T, whereas commitment is related to lower resting levels of T.

All these findings suggest that many women with low desire have difficulties in consciously perceiving T-related bodily and emotional changes that accompany the subjective experience of sexual desire, or perhaps even more general difficulties in perceiving emotional and bodily changes caused by other sexually motivating hormones and neurotransmitters. If this proves to be correct by further studies, there will be important implications for the therapy of low desire. Pharmacotherapies with T or other excitatory agents might be more effective in women with better emotional and bodily awareness (Brody 2009).

A review of studies on menopausal women revealed that T administration was more likely to be effective in increasing desire with supraphysiological doses and in the presence of estradiol (Cappelletti and Wallen 2016). It seems likely that a combination of estradiol and T is more effective in increasing desire than either alone. Moreover, menopausal women might require additional doses of estradiol due to lack of ovarian function. Nevertheless, there are studies showing that T alone can increase desire in menopausal women not taking estrogens (Davis et al. 2008; Sherwin et al. 1985). In another study with more than 70% of menopausal women not taking estrogens (Panay et al. 2010), T alone increased desire, and the obtained average T levels were not much above the normal range (67.9 ng/dl). Future studies might examine if there is a threshold beyond which T levels are more likely to modulate desire, and if it differs in menopausal women and women in their reproductive years. Moreover, our findings invite new avenues of research by calling attention to the role of emotional and bodily awareness, personality, and relationship status, in facilitating or hindering the effect of T on desire. Also, research on the relationship between T and desire will gain by incorporating other hormones, such as cortisol, estradiol and progesterone, as interactions between them are a possibility. Future research might test if lack of emotional and bodily awareness interferes in the modulation of desire by estradiol and other hormones.

On the other hand, psychotherapies aimed at increasing emotional and bodily awareness might be more effective in enhancing desire (Patersen et al. 2017; Silverstein et al. 2011) in women with an overactive inhibitory system, as they could ameliorate the attention to internal and external sexual cues, thereby allowing the action of the excitatory mechanisms. Additionally, our findings suggest that psychotherapies aiming at improving defensive functioning (Bond 2004) and reducing alexithymia (Spek et al. 2008; Taylor et al. 2016) might have beneficial effects on sexual desire, but research is needed to test their effects on sexual function.

Limitations of the study include the Portuguese convenience sample with many young university students, mostly not cohabiting, and not likely to have parental care, which can have effects on the association of T and desire (Costa et al. 2015).

We did not control for the mid-cycle peak of T in the naturally cycling women. It is not clear to what extent it can affect between-subject comparisons, as it seems inconsistent, often found to be absent (Bartley et al. 2015; Crewter and Cook 2018; Dawood and Saxena 1976; Feldman et al. 1978; Lobmaier et al. 2015; Mathor et al. 1985; Probst et al. 2018; Rhudy et al. 2013) or of small magnitude (Dabbs Jr and de La Rue 1991; Goebelsmann et al. 1974). More research is needed on the topic.

Although the FSFI desire dimension is likely not a golden standard, it appears to encompass a high variation of sexual desire with scores ranging from 2 to 10. It is sensitive to (variation in) hypoactive sexual desire reflected on scores lower than 6 (Gerstenberger et al. 2010; Witting et al. 2008). In the present study, the three higher scores (8, 9 and 10) were above the 75th percentile, and scores 9 and 10 were above the 90th percentile; thus, the scale appears to be sensitive to variation ranging from very low levels of desire to very high levels of desire.

Conclusion

The present findings are preliminary evidence that the link between T and desire is moderated by bodily and emotional awareness, especially so among women without a regular sexual partner.

References

Alexander, G. M., & Sherwin, B. B. (1991). The association between testosterone and sexual arousal, and selective attention for erotic stimuli in men. Hormones and Behavior, 25(3), 367–381.

Alexander, G. M., & Sherwin, B. B. (1993). Sex steroids, sexual behavior, and selection attention for erotic stimuli in women using oral contraceptives. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 18(2), 91–102.

Alexander, G. M., Swerdloff, R. S., Wang, C., Davidson, T., McDonald, V., Steiner, B., & Hines, M. (1997). Androgen-behavior correlations in hypogonadal men and eugonadal men. I. Mood and response to auditory sexual stimuli. Hormones and Behavior, 31(2), 110–119.

Andrews, G., Singh, M., & Bond, M. (1993). The defense style questionnaire. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 181(4), 246–256.

Apostolou, M. (2016). Understanding the prevalence of sexual dysfunctions in women: an evolutionary perspective. Adaptive Human Behavior and Physiology, 2(1), 26–43.

Barrett, L. F., Quigley, K. S., Bliss-Moreau, E., & Aronson, K. R. (2004). Interoceptive sensitivity and self-reports of emotional experience Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 87(5), 684–697.

Bartley, E. J., Palit, S., Kuhn, B. L., Kerry, T. L., Terry, E. L., DelVentura, J. L., & Rhudy, J. L. (2015). Natural variation in testosterone is associated with hypoalgesia in healthy women. Clinical Journal of Pain, 31(8), 730–739.

Basson, R., Brotto, L. A., Petkau, A. J., & Labrie, F. (2010). Role of androgens in women’s sexual dysfunction. Menopause, 17(5), 962–971.

Blaya, C., Dornelles, M., Blaya, R., Kipper, L., Hedlt, E., Isolan, L., et al. (2007). Brazilian–Portuguese version of defensive style questionnaire-40 for the assessment of defense mechanisms: construct validity study. Psychotherapy Research, 17(3), 261–270.

Bond, M. (2004). Empirical studies of defense style: relationships with psychopathology and change. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 12(5), 263–278.

Borsci, G., Boccardi, M., Rossi, R., Rossi, G., Perez, J., Bonetti, M., & Frisoni, G. B. (2009). Alexithymia in healthy women: a brain morphology study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 114(1–3), 208–215.

Brody, S. (2003). Alexithymia is inversely associated with women’s frequency of vaginal intercourse. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 32(1), 73–77.

Brody, S. (2009). Phosphodiesterase inhibitors and vaginal intercourse orgasm. International Journal of STD & AIDS, 20(6), 440.

Brody, S., & Costa, R. M. (2013). Associations of immature defense mechanisms with personal importance of junk food, television and alcohol are independent of age. Psychiatry Research, 210(3), 1327–1328.

Burnham, T. C., Chapman, J. F., Gray, P. B., McIntyre, M. H., Lipson, S. F., & Ellison, P. T. (2003). Men in committed, romantic relationships have lower testosterone. Hormones and Behavior, 44(2), 119–122.

Cacioppo, S., Bianchi-Demicheli, F., Frum, C., Pfaus, J. G., & Lewis, J. W. (2012). The common neural bases between sexual desire and love: a multilevel kernel density fMRI analysis. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 9(4), 1048–1054.

Cappelletti, M., & Wallen, K. (2016). Increasing women’s sexual desire: the comparative effectiveness of estrogens and androgens. Hormones and Behavior, 78, 178–193.

Casto, K. V., & Edwards, D. A. (2016). Before, during, and after: how phases of competition differentially affect testosterone, cortisol, and estradiol levels in women athletes. Adaptive Human Behavior and Physiology, 2(1), 11–25.

Costa, R. M., & Brody, S. (2013). Immature psychological defense mechanisms are associated with greater personal importance of junk food, alcohol, and television. Psychiatry Research, 209(3), 535–539.

Costa, R. M., & Oliveira, R. F. (2015). Maladaptive defense mechanisms are associated with decoupling of testosterone from sexual desire in women of reproductive age. Neuropsychoanalysis, 17(2), 121–134.

Costa, R. M., Correia, M., & Oliveira, R. F. (2015). Does personality moderate the link between women’s testosterone and relationship status? The role of extraversion and sensation seeking. Personality and Individual Differences, 76, 141–146.

Costa, R. M., Oliveira, T. F., Pestana, J., & Costa, D. (2016a). Self-transcendence is related to higher female sexual desire. Personality and Individual Differences, 96, 191–197.

Costa, R. M., Pestana, J., Costa, D., & Wittmann, M. (2016b). Altered states of consciousness are related to higher sexual responsiveness. Consciousness and Cognition, 42, 135–141.

Costa, R. M., Pestana, J., Costa, D., Pinto Coelho, M., Correia, S., & Gomes, S. (2018). Sexual desire, alexithymia, interoception, and heart rate variability. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 15(7, Suppl. 3), S175.

Crewter, B. T., & Cook, C. J. (2018). A longitudinal analysis of salivary testosterone concentrations and competitiveness in elite and non-elite women athletes. Physiology & Behavior, 188, 157–161.

Dabbs Jr., J. M., & de La Rue, D. (1991). Salivary testosterone measurements among women: Relative magnitude of circadian and menstrual cycles. Hormone Research, 35(5), 182–184.

Dabbs Jr., J. M., & Mohamed, S. (1992). Male and female salivary testosterone concentrations before and after sexual activity. Physiology & Behavior, 52(1), 195–197.

Das, A., & Sawin, N. (2016). Social modulation or hormonal causation? Linkages of testosterone with sexual activity and relationship quality in a nationally representative longitudinal sample of older adults. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 45(8), 2101–2115.

Davis, S. R., Davison, S. L., Donath, S., & Bell, R. J. (2005). Circulating androgen levels and self-reported sexual function in women. JAMA, 294(1), 91–96.

Davis, S. R., Moreau, M., Kroll, R., Bouchard, C., Panay, N., Gass, M., et al. (2008). Testosterone for low libido in postmenopausal women not taking estrogen. New England Journal of Medicine, 359(19), 2005–2017.

Dawood, M. Y., & Saxena, B. B. (1976). Plasma testosterone and dihydrotestosterone in ovulatory and anovulatory cycles. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecolgy, 126(4), 430–435.

Dunn, B. D., Galton, H. C., Morgan, R., Evans, D., Oliver, C., Meyer, M., et al. (2010). Listening to your heart. how interoception shapes emotion experience and intuitive decision making. Psychological Science, 21(12), 1835–1844.

Edelstein, R. S., Chopik, W. J., & Kean, E. L. (2011). Sociosexuality moderates the association between testosterone and relationship status in men and women. Hormones and Behavior, 60(3), 248–255.

Edelstein, R. S., van Anders, S. M., Chopik, W. J., Goldey, K. L., & Wardecker, B. M. (2014). Dyadic associations between testosterone and relationship quality in couples. Hormones and Behavior, 65(4), 401–407.

Fallon, B. (2008). ‘Off-label’ drug use in sexual medicine treatment. International Journal of Impotence Research, 20(2), 127–134.

Feldman, F., Bain, J., & Matuk, A. R. (1978). Daily assessment of ocular and hormonal variables throughout the menstrual cycle. Archives of Ophthalmology, 96(10), 1835–1838.

Fiers, T., Delanghe, J., T’Sjoen, G., Van Caenegem, E., Wierckx, K., & Kaufman, J. M. (2014). A critical evaluation of salivary testosterone as a method for the assessment of serum testosterone. Steroids, 85, 5–9.

Freud, S. (1908/1953). ‘Civilized’ sexual morality and modern nervousness. In J. Strachey (Ed.), The standard edition of the complete psychological works of Sigmund Freud (Vol. IX, pp. 177–208). London: Hogarth Press.

Gerstenberger, E. P., Rosen, R. C., Brewer, J. V., Meston, C. M., Brotto, L. A., Wiegel, M., & Sand, M. (2010). Sexual desire and the female sexual function index (FSFI): A sexual desire cutpoint for clinical interpretation of the FSFI in women with and without hypoactive sexual desire disorder. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 7(9), 3096–3103.

Goebelsmann, U., Arce, J. J., Thorneycroft, I. H., & Mishell, D. R., Jr. (1974). Serum testosterone concentrations in women throughout the menstrual cycle and following HCG administration. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 119(4), 445–452.

Goerlich-Dobre, K. S., Votinov, M., Habel, U., Pripfl, J., & Lamm, C. (2015). Neuroanatomical profiles of alexithymia dimensions and subtypes. Human Brain Mapping, 36(10), 3805–3818.

Goldey, K. L., & van Anders, S. M. (2011). Sexy thoughts: effects of sexual cognitions on testosterone, cortisol, and arousal in women. Hormones and Behavior, 59(5), 754–764.

Goldey, K. L., Conley, T. D., & van Anders, S. M. (2018). Dynamic associations between testosterone, partnering, and sexuality during the college transition in women. Adaptive Human Behavior and Physiology, 4(1), 42–68.

Gray, P. B., Kahlenberg, S. M., Barrett, E. S., Lipson, S. F., & Ellison, P. T. (2002). Marriage and fatherhood are associated with lower testosterone in males. Evolution and Human Behavior, 23(3), 193–201.

Gray, P. B., Campbell, B. C., Marlowe, F. W., Lipson, S. F., & Ellison, P. T. (2004). Social variables predict between-subject but not day-to-day variation in the testosterone of US men. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 29(9), 1153–1162.

Guay, A., & Jacobson, J. (2002). Decreased free testosterone and dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEA-S) levels in women with decreased libido. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy, 28(Suppl 1), 129–142.

Guay, A., Jacobson, J., Munarriz, R., Traish, A., Talakoub, L., et al. (2004). Serum androgen levels in healthy premenopausal women with and without sexual dysfunction: Part B: reduced serum androgen levels in healthy premenopausal women with complaints of sexual dysfunction. International Journal of Impotence Research, 16(2), 121–129.

Helmes, E., McNeill, P. D., Holden, R. R., & Jackson, C. (2008). The construct of alexithymia: associations with defense mechanisms. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 64(3), 318–331.

Herbert, B. M., Pollatos, O., & Schandry, R. (2007). Interoceptive sensitivity and emotion processing: an EEG study. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 65(3), 214–227.

Herbert, B. M., Pollatos, O., Flor, H., Enck, P., & Schandry, R. (2010). Cardiac awareness and autonomic reactivity during emotional picture viewing and mental stress. Psychophysiology, 47(2), 342–354.

Herbert, B. M., Herbert, C., & Pollatos, O. (2011). On the relationship between interoceptive awareness and alexithymia: is interoceptive awareness related to emotional awareness? Journal of Personality, 79(5), 1149–1175.

Hooper, A. E., Gangestad, S. W., Thomson, M. E., & Bryan, A. D. (2011). Testosterone and romance: the association of testosterone with relationship commitment and satisfaction in heterosexual men and women. American Journal of Human Biology, 23(4), 553–555.

Jones, B. C., Hahn, A. C., Fisher, C. I., Wang, H., Kandrik, M., & DeBruine, L. M. (2018). General sexual desire, but not desire for uncommitted sexual relationships, tracks changes in women’s hormonal status. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 88, 153–157.

Lobmaier, J. S., Probst, F., Perrett, D. I., & Heinrichs, M. (2015). Menstrual cycle phase affects discrimination of infant cuteness. Hormones and Behavior, 70, 1–6.

López, H. H., Hay, C. C., & Conklin, P. H. (2009). Attractive men induce testosterone and cortisol release in women. Hormones and Behavior, 56(1), 84–92.

Lumley, M. A., Stettner, L., & Wehmer, F. (1996). How are alexithymia and physical illness linked? A review and critique of pathways. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 41(6), 505–518.

Madioni, F., & Mammana, L. A. (2001). Toronto alexithymia scale in outpatients with sexual disorders. Psychopathology, 34(2), 95–98.

Mathor, M. B., Achado, S. S., Wajchenberg, B. L., & Germek, O. A. (1985). Free plasma testosterone levels during the normal menstrual cycle. Journal of Endocrinological Investigation, 8(5), 437–441.

Murphy, J., Brewer, R., Hobson, H., Catmur, C., & Bird, G. (2018). Is alexithymia characterised by impaired interoception? Further evidence, the importance of control variables, and the problems of heartbeat counting task. Biological Psychology, 136, 189–197.

Oliveira, G. A., & Oliveira, R. F. (2014). Androgen modulation of social decision making mechanisms in the brain: an integrative and embodied perspective. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 8, 209.

Panay, N., Al-Azzawi, F., Bouchard, C., Davis, S. R., Eden, J., Lodhi, I., et al. (2010). Testosterone treatment of HSDD in naturally menopausal women: the ADORE study. Climacteric, 13(2), 121–131.

Parker, J. D., Taylor, G. D., & bagby, R. M. (2003). The 20-item Toronto alexithymia scale. III. Reliability and factorial validity in a community population. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 55(3), 269–275.

Patersen, L. Q., Handy, A. B., & Brotto, L. A. (2017). A pilot study of eight-session mindfulness-based cognitive therapy adapted for women’s sexual interest/arousal disorder. Journal of Sex Research, 54(7), 850–861.

Poels, S., Bloemers, J., van Rooij, K., Goldstein, I., Gerritsen, J., van Ham, D., et al. (2013). Toward personalized sexual medicine (part 2): Testosterone combined with a PDE-5 inhibitor increases sexual satisfaction in women with HSDD and FSAD, and a low sensitive system for sexual cues. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 10(3), 810–823.

Pollatos, O., Herbert, B. M., Matthias, E., & Scandry, R. (2007). Heart rate response after emotional picture presentation is modulated by interoceptive awareness. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 63(1), 117–124.

Probst, F., Golle, J., Lory, V., & Lobmaier, J. S. (2018). Reactive aggression tracks within-participant changes in women’s salivary testosterone. Aggressive Behavior, 44(4), 326–371.

Rhudy, J. L., Bartley, E. J., Palit, S., Kerr, K. L., Kuhn, B. L., Martin, S. L., et al. (2013). Do sex hormones influence emotional modulation of pain and nociception in healthy women? Biological Psychology, 94(3), 534–544.

Riley, A., & Riley, E. (2000). Controlled studies on women presenting with sexual desire disorder: I. endocrine status. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 26(3), 269–283.

Roney, J. R., & Simmons, Z. L. (2013). Hormonal predictors of sexual motivation in natural menstrual cycles. Hormones and Behavior, 63(4), 636–645.

Roney, J. R., Lukaszewski, A. W., & Simmons, Z. L. (2007). Rapid endocrine responses of young men to social interactions with young women. Hormones and Behavior, 52(3), 326–333.

Rosen, R., Brown, C., Heiman, J., Leiblum, S., Meston, C., Shabsigh, R., et al. (2000). The female sexual function index (FSFI): a multidimensional self-report instrument for the assessment of female sexual function. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 26(2), 191–208.

Sakaguchi, K., Oki, M., Nonma, S., & Hasegawa, T. (2006). Influence of relationship status and personality traits on salivary testosterone among Japanese men. Personality and Individual Differences, 41(6), 1077–1087.

Santoro, N., Torrens, J., Crawford, S., Allsworth, J. E., Finkelstein, J. S., Golb, E. B., et al. (2005). Correlates of circulating androgens in mid-life women: the study of women’s health across the nation. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 90(8), 4836–4845.

Schultz, S. M. (2016). Neural correlates of heart-focused interoception: a functional magnetic resonance imaging meta-analysis. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences, 371(1708).

Sherwin, B. B., Gelfand, M. M., & Brender, W. (1985). Androgen enhances sexual motivation in females: a prospective, cross-over study of sex steroid administration in the surgical menopause. Psychosomatic Medicine, 47(4), 339–351.

Silverstein, R. G., Brown, A. C., Roth, H. D., & Britton, W. B. (2011). Effects of mindfulness training on body awareness to sexual stimuli: implications for female sexual dysfunction. Psychosomatic Medicine, 73(9), 817–825.

Spek, V., Nyklícek, I., Cuijpers, P., & Pop, V. (2008). Alexithymia and cognitive behaviour therapy outcome for subthreshold depression. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 118(2), 164–167.

Strigo, I. A., & Craig, A. D. (2016). Interoception, homeostatic emotions and sympathovagal balance. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 371(1708), 20160010.

Stuckey, B. G. (2008). Female sexual function and dysfunction in the reproductive years: the influence of endogenous and exogenous sex hormones. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 5(10), 2282–2290.

Taylor, G. J., Bagby, R. M., & Parker, J. D. (2003). The 20-item Toronto alexithymia scale. IV. Reliability and factorial validity in different languages and cultures. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 55(3), 277–283.

Taylor, G. J., Bagby, R. M., & Parker, J. D. (2016). What’s in the name ‘alexithymia’? A commentary on “affective agnosia: expansion of the alexithymia construct and a new opportunity to integrate and extend Freud’s legacy.”. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 68, 1006–1020.

Turna, B., Apaydin, E., Semerci, B., Altay, B., Cikili, N., & Nazli, O. (2005). Women with low libido: correlation of decreased androgen levels with female sexual function index. International Journal of Impotence Research, 17(2), 148–153.

van Anders, S. M. (2012). Testosterone and sexual desire in healthy women and men. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 41(6), 1471–1484.

van Anders, S. M., & Goldey, K. L. (2010). Testosterone and partnering are linked via relationship status for women and ‘relationship orientation’ for men. Hormones and Behavior, 58(5), 820–826.

van Anders, S. M., & Watson, N. V. (2007). Testosterone levels in women and men who are single, in long-distance relationships, or same-city relationships. Hormones and Behavior, 51(2), 286–291.

van Anders, S. M., Hamilton, L. D., Schmidt, N., & Watson, N. V. (2007). Associations between testosterone secretion and sexual activity in women. Hormones and Behavior, 51(4), 477–482.

van der Made, F., Bloemers, J., Yassem, W. E., Kleiverda, G., Everaerd, W., van Ham, D., et al. (2009). The influence of testosterone combined with a PDE5-inhibitor on cognitive, affective, and physiological sexual functioning in women suffering from sexual dysfunction. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 6(3), 777–790.

Veríssimo, R. (2001). The Portuguese version of the 20-item Toronto alexithymia scale -- I. linguistic adaptation, semantic validation, and reliability study. Acta Médica Portuguesa, 14(5–6), 529–536.

Wahlin-Jacobsen, S., Pedersen, A. T., Kristensen, E., Laessoe, N. C., Lundqvist, M., Cohen, A. S., et al. (2015). Is there a correlation between androgens and sexual desire in women? Journal of Sexual Medicine, 12(2), 358–373.

Wiens, S., Mezzacappa, E. S., & Katkin, E. S. (2000). Heartbeat detection and the experience of emtions. Cognition and Emotion, 14(3), 417–427.

Witting, K., Santtila, P., Varjonen, M., Jern, P., Johansson, A., von der Pahlen, B., & Sandnabba, K. (2008). Female sexual dysfunction, sexual distress, and sexual compatibility with partner. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 5(11), 2587–2599.

Woodis, C. B., McLendon, A. N., & Muzyk, A. J. (2012). Testosterone supplementation for hypoactive sexual desire disorder in women. Pharmacotherapy, 32(1), 38–53.

Zimmerman, Y., Eijkemans, M. J., Coelingh Bennink, H. J., Blankenstein, M. A., & Fauser, B. C. (2013). The effect of combined oral contraception on testosterone levels in healthy women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Human Reproduction Update, 20(1), 76–105.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia (grant numbers FRH/BPD/76130/2011 and UID/PSI/04810/2013); and Fundação BIAL (grant number 103/12).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Standards

The authors declare that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the laws of the country in which it was performed. The study was approved by the relevant institutional Ethics committee and complies with the principles of the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments. All participants provided informed consent before their inclusion in the study.

The authors state that they do not have financial relationships with the organizations that sponsored the research. The authors also state that they have full control of all primary data and that they agree to allow the journal to review their data if requested.

Conflict of Interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Costa, R.M., Oliveira, G., Pestana, J. et al. Do Psychosocial Factors Moderate the Relation between Testosterone and Female Sexual Desire? The Role of Interoception, Alexithymia, Defense Mechanisms, and Relationship Status. Adaptive Human Behavior and Physiology 5, 13–30 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40750-018-0102-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40750-018-0102-7