Abstract

This paper examines the relationship between interest rates and household saving rates for an uneven panel of 19 OECD countries during the period 1995–2018. Unlike earlier studies, it uses the pooled mean group methodology to investigate which of the interest rate effects, income or substitution, dominates in the short run, long run, or both periods. With the baseline estimations, I find that the income effect outweighs the substitution effect in the short run, and vice versa in the long run. I also find that inflation (both expected and actual), household wealth through housing prices, unemployment rate, current taxes on income and wealth, and general government debt have significant negative impact on household saving in the long run. I find that financial development has a positive effect on household saving in the long run. Current taxes on income and wealth have a strong negative impact on household saving in the short run.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Some central banks with negative interest rate policy include (note: adoption dates in parenthesis)—Danmarks National Bank (July 2012), European Central Bank (June 2014), Swiss National Bank (January 2015), Sveriges Riksbank (February 2015), Bank of Japan (January 2016), and National Bank of Hungary (March 2016).

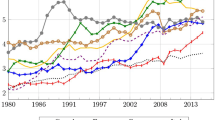

See Fig. 1 for the plots of the real gross saving rate for the panel and the EU. Individual country-plots are not shown but are available upon request.

See Gylfason (1993) for a tabulated historical overview of the effects of interest rates and inflation on aggregate consumption and saving in the USA.

See Hüfner and Koske (2010) for an overview of the determinants of household saving rates in panel studies.

Ul Haque et al. (1999) show that ignoring cross-country differences can result in the overestimation of the effects of certain factors on the private saving rates and at the same time obtain highly significant, but spurious, nonlinear effects for some of the potential determinants.

Aizenman et al. (2019) for a detailed discussion of the theoretical predictions of private saving.

A detailed theoretical formulation and analysis of short- and long-run mechanism, which has been ignored in the literature would offer useful insights; however, it is beyond the scope of this paper.

See Gylfason (1993) for an elaborative procedure and defence of the use of adaptive expectations rather than rational expectations. Although a market based expected inflation is preferable, survey data is not available for all countries in the panel; hence, the use of adaptive expectation method.

See Pesaran et al. (1999) for an elaborative discussion of the PMG estimation method.

The results did not significantly differ when the Akaike’s information criterion (AIC) was used to determine the optimal number of lags.

The approach is to start with a trivial regression and observe the results of subsequent addition of other variables. However, for some cases I present the baseline result directly.

Caution must be taken in comparing these results with other panel studies which use the real interest in its estimation.

The standard errors of the parameter estimates are a bit higher which suggest this equation might not fit the data quite well, as compared with model estimated with the expected rate of inflation.

The use of long-term nominal interest rates here is merely a distinct empirical exercise and should not to be viewed as a substitute for the short-term nominal interest rate in the hypothesis testing. Monetary policy is generally presumed to have a limited impact on the long-term rates.

I do not simultaneously add more than three policy variables to the benchmark model in order to ensure a sufficient number of degrees of freedom.

See Schmidt-Hebbel et al. (1992) for a tabulated long list of variables with their expected sign as well as the results of 16-panel studies of private saving.

Consumption tax, if it is linear, does not distort household’s intertemporal decision. Wage and capital income taxes do influence the household’s intertemporal saving and consumption decisions.

Note that the one-year expected rate of inflation is already part of the baseline specification.

AIC is more reliable than a fixed lag; thus, ARDL (1, 1, 1, 1) since T is small in this study. Moreover, estimations with a common ARDL (1, 1, 1, 1) showed more evidence of misspecification than when the lag was chosen by AIC.

References

Aizenman, J., Y.-W. Cheung, and H. Ito. 2019. The interest rate effect on private saving: Alternative perspectives. Journal of International Commerce, Economics and Policy 10(01): 1950002.

Allais, M. 1947. Economic et interet (Imprimerie Nationale, Paris).

Attanasio, O.P., L. Picci, and A.E. Scorcu. 2000. Saving, growth, and investment: A macroeconomic analysis using a panel of countries. Review of Economics and Statistics 82(2): 182–211.

Bandiera, O., G. Caprio, P. Honohan, and F. Schiantarelli. 2000. Does financial reform raise or reduce saving? Review of Economics and statistics 82(2): 239–263.

Boskin, M.J. 1978. Taxation, saving, and the rate of interest. Journal of political Economy 86(2, Part 2): S3–S27.

Callen, M.T., and M.C. Thimann. 1997. Empirical determinants of household saving: evidence from OECD countries, number 97-181, International Monetary Fund.

Carlino, G.A. 1982. Interest rate effects and intertemporal consumption. Journal of Monetary Economics 9(2): 223–234.

Carroll, C.D., and D.N. Weil. 1993. Saving and growth: A reinterpretation. NBER Working Paper (w4470).

David, P.A., and J.L. Scadding. 1974. Private savings: Ultrarationality, aggregation, and’denison’s law. Journal of Political Economy 82 (2, Part 1): 225–249.

De Mello, L., P.M. Kongsrud, and R. Price. 2004. Saving behaviour and the effectiveness of fiscal policy. OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 397, Paris: OECD.

De Serres, A., and F. Pelgrin. 2002. The decline in private saving rates in the 1990s in OECD countries: How much can be explained by non-wealth determinants?.

Denison, E.F. 1958. A note on private saving. The Review of Economics and Statistics 40: 261–267.

Diamond, P.A. 1965. National debt in a neoclassical growth model. The American Economic Review 55(5): 1126–1150.

Edwards, S. 1996. Why are latin america’s savings rates so low? An international comparative analysis. Journal of Development Economics 51(1): 5–44.

Ferrucci G., and C. Miralles. 2007. Saving behaviour and global imbalances: The role of emerging market economies (No. 842). ECB Working Paper.

Gylfason, T. 1981. Interest rates, inflation, and the aggregate consumption function. The Review of Economics and Statistics 63: 233–245.

Gylfason, T. 1993. Optimal saving, interest rates, and endogenous growth. The Scandinavian Journal of Economics 95(4): 517–533.

Horioka, C.Y., and J. Wan. 2007. The determinants of household saving in china: A dynamic panel analysis of provincial data. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 39(8): 2077–2096.

Houthakker H.S., and L.D. Taylor. 1970. Consumer demand in the united states, 2nd ed. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Howard, D.H. 1978. Personal saving behavior and the rate of inflation. The Review of Economics and Statistics 60: 547–554.

Howrey, E.P., and S.H. Hymans. 1978. The measurement and determination of loanable-funds saving. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 3: 655–685.

Hüfner, F., and I. Koske. 2010. Explaining household saving rates in g7 Countries: Implications for GERMANY. OECD Economics Department Working Papers No. 754, 0_1.

Im, K.S., M.H. Pesaran, and Y. Shin. 2003. Testing for unit roots in heterogeneous panels. Journal of Econometrics 115(1): 53–74.

Juster, F.T., and L.D. Taylor. 1975. Towards a theory of saving behavior. The American Economic Review 65(2): 203–209.

Juster, F.T., and P. Wachtel. 1972. A note on inflation and the saving rate. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 3: 765–778.

Keynes, J.M. 1936. The general theory of employment, interest and money (1936). Whitefish: Kessinger Publishing.

Levin, A., C.-F. Lin, and C.-S.J. Chu. 2002. Unit root tests in panel data: Asymptotic and finite-sample properties. Journal of Econometrics 108(1): 1–24.

Loayza, N., K. Schmidt-Hebbel, and L. Servén. 2000. What drives private saving across the world? Review of Economics and Statistics 82(2): 165–181.

Masson, P.R., T. Bayoumi, and H. Samiei. 1998. International evidence on the determinants of private saving. The World Bank Economic Review 12(3): 483–501.

Mody, A., F. Ohnsorge, and D. Sandri. 2012. Precautionary savings in the great recession. IMF Economic Review 60(1): 114–138.

Nabar M.M. 2011. Targets, interest rates, and household saving in urban China, number 11-223, International Monetary Fund.

Pesaran, M.H. 2007. A simple panel unit root test in the presence of cross-section dependence. Journal of Applied Econometrics 22(2): 265–312.

Pesaran, M.H., Y. Shin, and R.P. Smith. 1999. Pooled mean group estimation of dynamic heterogeneous panels. Journal of the American Statistical Association 94(446): 621–634.

Rocher S., M. Stierle. et al. 2015. Household saving rates in the EU: Why do they differ so much? Technical report.

Salotti, S. 2010. Global imbalances and household savings: The role of wealth. The Social Science Journal 47(1): 21–44.

Samuelson, P.A. 1958. An exact consumption-loan model of interest with or without the social contrivance of money. Journal of Political Economy 66(6): 467–482.

Schmidt-Hebbel, K., S.B. Webb, and G. Corsetti. 1992. Household saving in developing countries: First cross-country evidence. The World Bank Economic Review 6(3): 529–547.

Summers, L.H. 1981. Capital taxation and accumulation in a life cycle growth model. The American Economic Review 71(4): 533–544.

Ul Haque, N., M.H. Pesaran, and S. Sharma. 1999. Neglected heterogeneity and dynamics in cross-country savings regressions. IMF Working Paper. Washington: International Monetary Fund.

Weber, W.E. 1970. The effect of interest rates on aggregate consumption. The American Economic Review 60(4): 591–600.

Zee, M.H.H., and M.V. Tanzi. 1998. Taxation and the household saving rate: Evidence from OECD countries, International Monetary Fund.

Acknowledgements

I thank Paulo Brito, Antonio Afonso, and participants of the INFER Workshop on New Challenges for Fiscal Policy for helpful insights and discussions. I also acknowledge useful comments of two anonymous referees. The paper represents the authors' personal opinions and does not reflect the views of the affiliated institution.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix: Data Descriptions and Sources

Appendix: Data Descriptions and Sources

Real Gross Saving Rate (in percent of gross disposable income)—\(s_{i t}^{rg}\): Saving of households and non-profit institutions serving households (NPISH) without deducting consumption of fixed capital and deflated by the price deflator private final consumption expenditure. Source: AMECO database.

Real Net Saving Rate (in percent of gross disposable income)—\(s_{i t}^{rn}\): Saving of households and non-profit institutions serving households (NPISH) after deducting consumption of fixed capital and deflated by the private final consumption expenditure. Source: AMECO database.

Short-term Nominal Interest Rate—\(i_{i t}^{sn}\): Mainly policy interest rates or 3-months money market rates. Source: AMECO database.

Long-term Nominal Interest Rate—\(i_{i t}^{ln}\): Mainly Central Government bonds of over 10 years. Source: AMECO database.

Long-term Real Interest Rate—\(i_{i t}^{lr}\): Long-term nominal interest rate (iln) adjusted for price deflator private final consumption expenditure. Source: AMECO database.

Unemployment Rate—\(u_{i t}\): Share of the total active population (labour force). Source: AMECO database.

Current Taxes on Income and Wealth—\(t_{i t}\): Comprise taxes on income from employment, property, entrepreneurship, pensions, etc., including taxes deducted by employers (PAYE taxes) and other current taxes on capital, poll taxes, levied per adult or per household, independently of income or wealth, expenditure taxes, payable on the total expenditures of persons or households. Source: AMECO database.

General Government Gross Debt—\(gd_{i t}\): General government net financial liabilities as percent of GDP. Source: AMECO database. Given the lack of general public debt data for some countries such as Switzerland, central government debt data is used as an alternative.

Domestic credit to private sector (as a percentage of GDP—\(dcr_{i t}\)): Financial resources provided to the private sector by financial corporations, such as through loans, purchases of non-equity securities, and trade credits and other accounts receivable, that establish a claim for repayment. Source: IMF, IFS, and World Bank and OECD GDP estimates.

Real Housing Price Index—\(hpr_{i t}\): Nominal house price indices deflated by the consumer price index. Source: OECD Analytical database.

Expected Inflation—\(\pi _{i t}^{e}\): Computed (on the assumption of adaptive expectations of price expectations) from the annual rate of change (\(\Delta pcdef\)) of the price deflator private final consumption expenditure (pcdef) in per cent per annum with adjustment weights (\(\lambda\)) varying from 0.1 to 1. Series with the best prediction of dpcd was used as expected rate of inflation:

Rate of Inflation—\(\pi _{i t}\): Computed as annual rate of change of the price deflator private final consumption expenditure (pcd) in percent per annum:

Similar results could be obtained with:

Source: Author’s computation.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Opoku, P.K. The Short-Run and Long-Run Determinants of Household Saving: Evidence from OECD Economies. Comp Econ Stud 62, 430–464 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41294-020-00123-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41294-020-00123-2

Keywords

- Household saving

- Interest rates

- Inflation

- Taxation

- Unemployment rate

- Dynamic heterogeneous panel data model