Abstract

There is growing evidence that frequent residential relocation is often associated with adverse socio-economic outcomes related to education, health and wellbeing. Prior research aimed at exploring the extent of residential movement has usually been restricted to survey evidence or infrequent census data. This study makes use of newly linked administrative data to design a framework for quantifying different levels and types of residential movement for an entire population. Within this context, we are able to derive working definitions for the transient and vulnerable transient. We also assess their interaction with a number of social service providers as well as important life events, both prior to and during the sample period. Our research contributes to understanding the key risk factors (in terms of both experience and intensity) associated with transience for adults, youth and children.

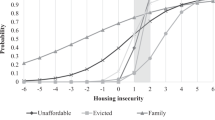

Source: Matched population between Census 2013 and address table in the IDI. Number of moves based on information from address table. Authors’ compilation (Numerical data for table is available upon author request)

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Changes in neighbourhood qualities and social characteristics, associated with residential movement, may also influence labour market activities and employment outcomes (Weinberg et al. 2004; Bayer et al. 2005; Oishi 2010). This highlights the complexity of this field of research where the same factors can be both determinants and outcomes (of frequent moves).

Note this is not the case for homeless individuals.

Territorial local authorities are geographic units defined under the Local Government Act—there are 67 of these units across NZ (Statistics NZ 2017). In our preliminary analysis we find that 93% of the sample population only moved within a region, and among them, 97% only moved within a territorial local authority over the three-year reference period.

Data was collected on five occasions—when the child was 9 months, three, five, seven, and 11 years.

Note that while there was usually a 5 year gap between Census waves, there was a 7 year gap between the 2006 and 2013 waves, due the impacts of the Christchurch earthquake in 2011.

Comprehensive information about the IDI is available through the Statistics NZ website at http://archive.stats.govt.nz/browse_for_stats/snapshots-of-nz/integrated-data-infrastructure.aspx.

The majority of health care in NZ is publicly funded through taxation. The Ministry of Health oversees this sector, while much of the day-to-day business, and around three quarters of the funding, is administered by district health boards (DHBs). This includes funding for primary care, hospital services, public health services, aged care services, and services provided by other non-government health providers. Primary health organisations ensure the provision of essential primary health care services, mostly through general practices and nurses, to people who are enrolled (i.e. registered) with the PHO.

The National Health Index number is a unique identifier that is assigned to every person who uses health and disability support services in NZ.

Note that because we do not know the composition of this potential group, it is difficult to speculate regarding the direction of impact on the quantification of transient and vulnerable transient persons.

We also conducted the Census versus address table comparison based on the second question in Table 2. The match rate was 79% and 80% for movers and non-movers, respectively.

This final exclusion was minor in nature and only related to 1461 individuals.

This is in line with the classification used by Rumbold et al. (2012) and Hutchings et al. (2013), who show that children who are subjected to at least one residential move per year on average (based on the total number of moves they consider in a given period), are at a greater risk of suffering from mental health problems and poor academic outcomes.

A meshblock is the smallest geographic unit used by Statistics NZ. The median size of this unit was 87 people (across 35 households) in 2006—see Meehan et al. (2018).

Except for demographic characteristics, which are based on the start of the reference period—01 August 2013.

We are unable to rescale these intensity variables for consistency due to the structure of the relevant datasets.

References

Andreasen, M. H., & Agergaard, J. (2016). Residential mobility and homeownership in Dar es Salaam. Population and Development Review, 42(1), 95–110.

Arsen, D., Plank, D., & Sykes, G. (1999). School choice policies in Michigan: The rules matter. For full text: http://edtech.connect.msu.edu/choice/conference/default.asp. Accessed 20 Sept 2017.

Baker, E., Bentley, R., Lester, L., & Beer, A. (2016). Housing affordability and residential mobility as drivers of locational inequality. Applied Geography, 72, 65–75.

Barnett, R., & Barnett, P. (2004). Primary health care in New Zealand: Problems and policy approaches. Social Policy Journal of New Zealand, 21, 49–66.

Bayer, P., Ross, S., & Topa, G. (2005). Place of work and place of residence: Informal hiring networks and labor market outcomes (No. w11019). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Beck, B., Buttaro, A., Jr., & Lennon, M. C. (2016). Home moves and child wellbeing in the first five years of life in the United States. Longitudinal and Life Course Studies: International Journal., 7(3), 240–264.

Bender, K., Ferguson, K., Thompson, S., Komlo, C., & Pollio, D. (2010). Factors associated with trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder among homeless youth in three US cities: The importance of transience. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 23(1), 161–168.

Böheim, R., & Taylor, M. P. (2002). Tied down or room to move? Investigating the relationships between housing tenure, employment status and residential mobility in Britain. Scottish Journal of Political Economy, 49(4), 369–392.

Bull, A., & Gilbert, J. (2007). Student movement and schools—What are the issues?. Evaluation and Social Assessment, Wellington: Centre for Research.

Butler, E. W., McAllister, R. J., & Kaiser, E. J. (1973). The effects of voluntary and involuntary residential mobility on females and males. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 35, 219–227.

Champion, T., & Shuttleworth, I. (2015a). Are people moving home less? An analysis of address changing in England and Wales, 1971–2011, using the ONS longitudinal study. London: London School of Economics, UK Spatial Economics Research Centre.

Champion, T., & Shuttleworth, I. (2015b). Is internal migration slowing? An analysis of four decades of NHSCR records for England and Wales. London: UK Spatial Economics Research Centre, London School of Economics.

Clark, W. A., & Davies Withers, S. (1999). Changing jobs and changing houses: Mobility outcomes of employment transitions. Journal of Regional Science, 39(4), 653–673.

Clark, W. A., Deurloo, M., & Dieleman, F. (2006). Residential mobility and neighbourhood outcomes. Housing Studies, 21(3), 323–342.

Clark, W. A., & Huang, Y. (2003). The life course and residential mobility in British housing markets. Environment and Planning A, 35(2), 323–339.

Cooke, T. J. (2011). It is not just the economy: Declining migration and the rise of secular rootedness. Population, Space and Place, 17, 193–203.

Cooke, T. J. (2013). Internal migration in decline. The Professional Geographer, 65(4), 664–675.

Cooke, T. J., & Shuttleworth, I. (2017). The effects of information and communication technologies on residential mobility and migration. Population, Space and Place, 24(3), 1–11.

Coulter, R., & Scott, J. (2015). What motivates residential mobility? Re-examining self-reported reasons for desiring and making residential moves. Population, Space and Place, 21(4), 354–371.

Coulter, R., van Ham, M., & Findlay, A. M. (2016). Re-thinking residential mobility: Linking lives through time and space. Progress in Human Geography, 40(3), 352–374.

Currie, J., & Madrian, B. C. (1999). Health, health insurance and the labor market. Handbook of Labor Economics, 3, 3309–3416.

Damm, A. P. (2014). Neighborhood quality and labor market outcomes: Evidence from quasi-random neighborhood assignment of immigrants. Journal of Urban Economics, 79, 139–166.

Darlington, F., Norman, P., & Gould, M. (2015). Migration and health. Internal Migration: Geographical perspectives and processes. Farnahm: Ashgate.

Desmond, M., Gershenson, C., & Kiviat, B. (2015). Forced relocation and residential instability among urban renters. Social Service Review, 89(2), 227–262.

Ding, L., Hwang, J., & Divringi, E. (2016). Gentrification and residential mobility in Philadelphia. Regional Science and Urban Economics, 61, 38–51.

Dong, M., Anda, R. F., Felitti, V. J., Williamson, D. F., Dube, S. R., Brown, D. W., et al. (2005). Childhood residential mobility and multiple health risks during adolescence and adulthood: the hidden role of adverse childhood experiences. Archives of Paediatrics & Adolescent medicine, 159(12), 1104–1110.

Exeter, D. J., Sabel, C. E., Hanham, G., et al. (2015). Movers and stayers: The geography of residential mobility and CVD hospitalisations in Auckland, New Zealand. Social Science and Medicine, 133, 331–339.

Falkingham, J., Sage, J., Stone, J., & Vlachantoni, A. (2016). Residential mobility across the life course: Continuity and change across three cohorts in Britain. Advances in Life Course Research, 30, 111–123.

Fitchen, J. M. (1994). Residential mobility among the rural poor 1. Rural Sociology, 59(3), 416–436.

Gambaro, L., & Joshi, H. (2016). Moving home in the early years: What happens to children in the UK. Longitudinal and Life Course Studies: International Journal., 7(3), 265–287.

German, D., Davey, M. A., & Latkin, C. A. (2007). Residential transience and HIV risk behaviors among injection drug users. AIDS and Behavior, 11(2), 21–30.

Gray, C. L., & Mueller, V. (2012). Natural disasters and population mobility in Bangladesh. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 109(16), 6000–6005.

Hawkins, J. D., Herrenkohl, T., Farrington, D., Brewer, D., Catalano, R., Harachi, T., & Cothern, L. (2000). Predictors of youth violence (OJJDP Juvenile Justice Bulletin). Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention.

Haynie, D. L., & South, S. J. (2005). Residential mobility and adolescent violence. Social Forces, 84(1), 361–374.

Heller, T. (1982). The effects of involuntary residential relocation: A review. American Journal of Community Psychology, 10(4), 471–492.

Hutchings, H. A., Evans, A., Barnes, P., Demmler, J., Heaven, M., Hyatt, M. A., et al. (2013). Do children who move home and school frequently have poorer educational outcomes in their early years at school? An anonymised cohort study. PloS One, 8(8), e70601.

Jelleyman, T., & Spencer, N. (2008). Residential mobility in childhood and health outcomes: A systematic review. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 62(7), 584–592.

Lupton, R. (2016). Housing policies and their relationship to residential moves for families with young children. Longitudinal and Life Course Studies: International Journal, 7, 288–301.

Magdol, L. (2002). Is moving gendered? The effects of residential mobility on the psychological well-being of men and women. Sex Roles, 47(11–12), 553–560.

Meehan, L., Pacheco, G., & Pushon, Z. (2018). Explaining ethnic disparities in bachelor’s degree participation: evidence from NZ. Studies in Higher Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2017.1419340.

Michielin, F., & Mulder, C. H. (2008). Family events and the residential mobility of couples. Environment and Planning A, 40(11), 2770–2790.

Mikolai, J., & Kulu, H. (2018). Short-and long-term effects of divorce and separation on housing tenure in England and Wales. Population Studies, 72(1), 17–39.

Mollborn, S., Lawrence, E., & Root, E. D. (2018). Residential mobility across early childhood and children’s kindergarten readiness. Demography, 12, 1–26.

Molloy, R., Smith, C. L., & Wozniak, A. (2011). Internal migration in the United States. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 25(2), 1–42.

Montgomery, J. D. (1994). Weak ties, employment, and inequality: An equilibrium analysis. American Journal of Sociology, 99(5), 1212–1236.

Morris, T. (2017). Examining the influence of major life events as drivers of residential mobility and neighbourhood transitions. Demographic Research, 36, 1015–1038.

Morton, S. M. B., Atatoa Carr, P. E., Berry, S. D., Grant, C. C., Bandara, D. K., Mohal, J., et al. (2014). Growing Up in New Zealand: A longitudinal study of New Zealand children and their families. Residential mobility report 1: Moving house in the first 1000 days. Auckland: Growing Up in New Zealand.

Mostafa, T. (2016). Measuring the impact of residential mobility on response: Evidence from the Millenium Cohort Study. Longitudinal and Life Course Studies: International Journal., 7(3), 201–217.

Naidu, A. (2009). Factors affecting patient satisfaction and healthcare quality. International Journal of Health Care Quality Assurance, 22(4), 366–381.

Norman, P., Boyle, P., & Rees, P. (2005). Selective migration, health and deprivation: A longitudinal analysis. Social Science and Medicine, 60(12), 2755–2771.

Oishi, S. (2010). The psychology of residential mobility implications for the self, social relationships, and well-being. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 5(1), 5–21.

Özüekren, A. S., & Van Kempen, R. (2002). Housing careers of minority ethnic groups: Experiences, explanations and prospects. Housing Studies, 17(3), 365–379.

Phinney, R. (2013). Exploring residential mobility among low-income families. Social Service Review, 87(4), 780–815.

Polio, D. E. (1997). The relationship between transience and current life situation in the homeless services-using population. Social Work, 42(6), 541–551.

Rumbold, A. R., Giles, L. C., Whitrow, M. J., Steele, E. J., Davies, C. E., Davies, M. J., et al. (2012). The effects of house moves during early childhood on child mental health at age 9 years. BMC Public Health, 12(1), 583.

Schafft, K. A. (2006). Poverty, residential mobility, and student transiency within a rural New York school district. Rural Sociology, 71(2), 212–231.

Schwartz, A. E., Corcoran, S., Siskin, L. S., et al. (2015). Moving matters: The causal effect of moving schools on student performance. IESP Working Paper 01-15.

Skobba, K., & Goetz, E. G. (2013). Mobility decisions of very low-income households. Cityscape, 15, 155–172.

Statistics New Zealand. (2006). QuickStats about population mobility: 2006 Census. Retrieved from http://www.stats.govt.nz/Census/2006CensusHomePage/QuickStats/quickstats-about-a-subject/population-mobility.aspx. September 2017.

Statistics New Zealand. (2013). Internal migration update. Retrieved from http://www.stats.govt.nz/browse_for_stats/population/Migration/internal-migration/tables.aspx#internal. September 2017.

Statistics New Zealand. (2017). Classification of territorial authority. Retrieved from http://archive.stats.govt.nz/methods/classifications-and-standards/classification-related-stats-standards/territorial-authority.aspx. September 2017.

Stokols, D., Shumaker, S. A., & Martinez, J. (1983). Residential mobility and personal well-being. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 3(1), 5–19.

Warner, C. (2016). The effect of incarceration on residential mobility between poor and nonpoor neighborhoods. City and Community, 15(4), 423–443.

Warner, C., & Sharp, G. (2016). The short-and long-term effects of life events on residential mobility. Advances in Life Course Research, 27, 1–15.

Weinberg, B. A., Reagan, P. B., & Yankow, J. J. (2004). Do neighborhoods affect hours worked? Evidence from longitudinal data. Journal of Labor Economics, 22(4), 891–924.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to several individuals and organisations for providing us with helpful comments. This includes the Social Policy Evaluation and Research Unit—Superu (Jason Timmins and John Wren); Victoria University of Wellington (Phillip Morrison) and Statistics NZ’s microdata team. We also thank Superu for sponsoring this research. Any errors or omissions remain the responsibility of the authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Disclaimer

The results in this article are not official statistics, they have been created for research purposes from the Integrated Data Infrastructure (IDI), managed by Statistics NZ. The opinions, findings, recommendations, and conclusions expressed in this article are those of the author(s), not Statistics NZ. Access to the anonymised data used in this study was provided by Statistics NZ in accordance with security and confidentiality provisions of the Statistics Act 1975. Only people authorised by the Statistics Act 1975 are allowed to see data about a particular person, household, business, or organisation, and the results in this report have been confidentialised to protect these groups from identification. Careful consideration has been given to the privacy, security, and confidentiality issues associated with using administrative and survey data in the IDI. Further detail can be found in the Privacy impact assessment for the Integrated Data Infrastructure available from http://www.stats.govt.nz.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jiang, N., Pacheco, G. & Dasgupta, K. Understanding the transient population: insights from linked administrative data. J Pop Research 36, 111–136 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12546-019-09223-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12546-019-09223-y