Abstract

The historical and professional identity of prospective history teachers seems to be central to understanding how these future teachers think of their educational action in articulation with their view of what it means to be historically competent in line with the development of historical literacy and more sophisticated historical consciousness. Thus, in the context of the Master’s Degree in History Teaching in the 3rd Cycle of Basic Education and in Secondary Education offered by the University of Minho (Portugal), following an investigative approach characterised by a Mixed Method in a longitudinal framework, data were collected through an open-answer questionnaire followed by a closed-answer questionnaire. The open-answer questionnaire was proposed at the beginning of the training of prospective History teachers and at the end of the same training course. About twenty answers were obtained and, through their analysis, essentially two types of identities emerged: one more in line with management professionalism and another with the emerging democratic professionalism. Based on the qualitative data, which was analysed inductively, a closed-answer questionnaire was created, intended to understand, through quantitative analysis, the ideas of future Portuguese History teachers about the purposes of being a History teacher, what it means to think historically, what kind of History class they identify with, what should students learn in History classes and whether they should use the terms ‘we’ or ‘the Portuguese’ when presenting the proposals for studying the national historical reality. This questionnaire was applied to students from various Master’s Degree courses in History Teaching, in a purposeful sampling considering the location of Portuguese universities, namely the University of Minho, University of Porto, University of Coimbra, University of Lisbon, and NOVA University of Lisbon.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction: historical and professional identity(ies)–reflections of historical consciousness on history education

The temporal orientation of life can vary based on the type of historical consciousness one develops and the type of perspective it forms. Thus, what we remember works like a mirror reflecting the levels of interest in the content and the attitudes arising therefrom over time. Historical memory mirrors individual ways of life, in the form of syntheses of discernible experiences and expectations. Temporal orientation promotes the way in which we make sense of the past.

The formation of our identity formation is also an important element for historical awareness. Historical consciousness relates to identity via the extension of the significance of the temporal process given to the ‘I’, to the ‘we’ and the transcendence of an individual life segment. Through historical identity, the person becomes part of a temporal whole that is larger than their own life. At the same time, historical consciousness inscribes social and cultural time in itself. It is said, for example, that to be a Christian is to be within a community, or more precisely, to know and feel a temporal body of a community in a certain way. The time elapsed between the origins and the present of a given people is indicative of the depth and intensity of the value indexed to national esteem (Rüsen, 2001). In this context, two essential functions can be ascribed to historical awareness: temporal orientation and identity creation.

Historical consciousness is viewed here as a conscious and unconscious experience of significant relations between the present and the past(s) and expectation horizons; it combines cognitive and emotional, empirical and normative, and is expressed narratively. Through historical awareness, the orientation of the present and the expectations of the future are deepened, based on historical research that generates multiple meanings for the past.

The idea is disseminated that historical education proposes to articulate metahistorical concepts with substantive concepts of History as a process of historical research experience that develops gradually in terms of sophistication. In this sense, historical education that fosters historical literacy, and allows for a more complex and multi-sided understanding of the world, is one of the drivers of the development of historical consciousness in the individual (the ‘I’) and in societies (the ‘us’), in favour of a historical consciousness and a humanistic identity that is more focused on what unites us than on what divides us.

This complex process of skill development must be guided by reflective history teachers, who are aware of their beliefs, their values and their attitudes, as well as of their responsibility as educators. Teacher training in Portugal has undergone changes that echo the new approaches to promoting reflection among teachers, in conjunction with higher education, and that suggest teaching professionalism profiles. It should be noted that the ideological charge inherent to the study and teaching of History creates an even more pressing need for reflection on the part of History teachers about the nature of their field of knowledge, about perspectives on substantive historical content, and about ways to promote the development of historical competences from intercultural proposals, based on various lines of research.

Teaching professionalism is a socially and culturally constructed concept, which is, of course, in line with the historical context and the political, economic and social demands of the respective community. This work proposes focusing attention on two specific concepts: managerial professionalism and democratic professionalism.

Managerial professionalism stems from a culture characterised by a performance and accountability agenda, in which it is argued that everything can be resolved through efficient management. Thus, in this conceptual framework, the teaching profession is based on bureaucracy, which is justified by ideas of decentralisation, and on practices that are evaluated taking into account measurable and quantifiable results, often presented in the form of performance rankings. In this professional development framework, the teacher works towards a set of pre-established external goals and documents their professional performance in detail. Thus, the teacher embodies a corporate identity, obeying political imperatives imposed by entities external to the school. This way of viewing the teaching activity suggests that the teacher is individualistic, competitive, controlling and a regulator of the process.

In a culture where the agenda focuses on a holistic development, practices and ideas can emerge that are based on what can be called ‘democratic professionalism’. This context of professional development of the teacher fosters the forging of alliances both between the various teachers and between them and other educational agents. The teacher’s action is thought and carried out from a perspective of collaboration and cooperation, in which everyone develops in the process. The teacher’s responsibilities are extended, with a view to building a more just and democratic society, through research and pedagogical-educational innovation. The instrumentalist logic of meeting external demands is thus replaced by an articulation between the pedagogical-educational action of the teacher and broad societal values and ideals. Thus, the action of this teacher is geared towards research and collaborative classrooms, which allow for democratic perceptions and experiences. It is suggested that a teacher who demonstrates an activist position may develop a greater number of learning experiences conducive to analysis, criticism and reflection, and the discussion of ideas and practices inside and outside the classroom. On the other hand, such an attitude will involve interaction with peers in an atmosphere of respect and trust. In other words, the way in which the teaching-learning process is thought and carried out is anchored on social constructivism.

Research in the fields of Teaching Professionalism and Teacher Training has suggested that the most widespread scenario is that of the so-called ‘managerial professionalism’ as we can see, for example, in the research data gathered by the Latin American Network of Teacher Work Studies (RedEstrado) and by Teachers Exercising Leadership (TEL) in Portugal (Sachs and Mockler, 2012; Flores, 2011, 2012).

It seems necessary to promote the awareness of ideas, goals and purposes, as well as to promote their implementation, particularly among teachers. This is an endeavour that should be pursued not only because of the benefits it will bring to students’ learning, but also because it is a means of preventing problems related to professional frustration, disenchantment and burnout among teachers (Korthagen, 2003; Korthagen and Vasalos, 2005). This awareness is extremely important, as the teacher can place the emphasis on a problematic situation that might have arisen (environment, behaviour, competences, beliefs…) or deepen their thinking to levels of reflection that can create new possibilities, in line with the proposal of the ‘onion model’ (Korthagen and Vasalos, 2005). In other words, it is necessary that teachers and/or future teachers think about ideals and boundaries in order to achieve the educational ideal. And it is from this intertwining of knowledge and relationships that professional identity is built. In times of rapid change, identity cannot be thought of as something that is ‘fixed’, but rather as something that is open-ended, ever-changing, ambiguous, negotiated and the result of experiences—historical awareness.

In view of the scenarios of professionalism in teaching identified, it seems essential to hear the ‘voice of the teacher and the voice of the student’ (Schmidt, 2016, p. 30). Again, it is vital to give the teacher/future teacher a voice and to value the teaching profession from within, i.e., from the ideas of teachers themselves, as intellectuals who are experts in their specific area of knowledge and in the pedagogical-educational field.

This study aims to answer the following research question: what historical and professional identity of future history teachers’ in Portugal seems to have, and if their academic and professional training is reflected in the construction of that identity?

The History teacher training model in Portugal

In Portugal, the model followed for the initial training of History teachers has undergone a few changes following the entry into force of the Bologna Process (Decree-Law No. 43/2007 of 22 February), which introduced the Master’s Degree as the qualification for teaching. As of 2008/09 the training of History teachers became bidisciplinary, carried out jointly with the area of Geography, with a duration of two academic years, conducive to the Master’s Degree in Teaching of History and Geography in the 3rd Cycle of Basic Education and in Secondary Education (MDTHG). Decree-Law no. 79/2014 established the legal framework for professional qualification for teaching, but now with separate professionalisations in Geography and History (Master’s Degree in Geography Teaching in the 3rd Cycle of Basic Education and in Secondary Education–MDGT–and Master’s Degree in History Teaching in the 3rd Cycle of Basic Education and in Secondary Education–MDHT). Official policies acknowledged the difficulties inherent to this bidisciplinary Master’s Degree, which required that students of the History Degree course attended curricular units of the area of Geography and students of the Geography Degree course attended History units. This change resulted in clear benefits for the specific training of both scientific areas (both for didactic units and for the teaching area) and, mainly, for basic training, which corresponds to 180 credits in the History Degree.

In order to become a History teacher in Portugal, and to access the national teacher placement programme in the best conditions, candidates need a professionalisation in History teaching, which is currently obtained by completing the Master’s Degree in History Teaching in the 3rd Cycle of Basic Education and in Secondary Education (MDHT). In order to access the Master’s Degree in History Teaching, students must have a degree (3 years) and, cumulatively, 120 credits (European Credit Transfer System–ECTS) in History, as well as a certificate of oral and written proficiency in Portuguese (Decree-Law 79/2014). These History credits may have been obtained in History, Art History or Archaeology Degree courses, or similar courses, which attest to the scientific mastery in History of candidates to the Master’s Degree.

The Master’s Degree in History Teaching in the 3rd Cycle of Basic Education and in Secondary Education (MDHT) is a two-year programme. In the first year, at university, students attend Curricular Units in the Area of Teacher Training (ATT), General Educational Training (GET) and Training in Specific Didactics (TSD).

In the 2nd year of the Course, in addition to attending a number of curricular units at the university, students will complete the Initiation to Pedagogical Practice (IPP), i.e., the Professional Traineeship (3rd and 4th semesters), which includes the modules Initiation to Professional Practice (IPP) and design of a Supervised Pedagogical Intervention Project (SPIP), Seminars in the Area of Teaching and Supervised Practice (Traineeship) in schools that have protocols with universities, under the guidance of a cooperating teacher and a supervisor at the University. Within the scope of Pedagogical Practice, trainees must implement the Supervised Pedagogical Intervention Project (SPIP), develop a reflective portfolio and, at the end, prepare the Traineeship Report, which must be defended in public examinations (Vieira et al., 2013; Melo, 2015).

Analysing the curricular structure of the MDHTs in Portugal, it is found that Decree-Law 79/2014 provides for some leeway in the attribution of ECTS credits by higher education institutions to each of the three training areas. This makes for greater flexibility in the attribution of credits among the Area of teacher training (ATT) and General Education (GET) areas and in Training in Specific Didactics (TSD), thus achieving the desired alignment between the principles of this legal instrument and the autonomy of higher education institutions (Fig. 1).

In this context, we observed that fewer credits were attributed to the teaching area in the MDHTs of the University of Porto (UP) and of the University of Lisbon (UL), in favour of the General Education Training (GET) area, which gained more weight. In contrast, NOVA University of Lisboa (UNL), University of Coimbra (UC) and University of Minho (UM) have kept the same credits for the Teaching area, reinforcing General Education (GET), although the area of Training in Specific Didactics (TSD) is given more prominence at the University of Coimbra. Initiation to Pedagogical Practice (IPP) is slightly more significant at NOVA University of Lisbon (UNL) and grants slightly fewer credits at the University of Minho. It appears that universities have generally opted for a greater appreciation of the areas of General Education (GET) and Specific Didactics (TSD), to the detriment of the Area of Teacher Training (ATT), despite the fact that the Decree-Law allows allocating more ECTS credits to this training area.

An analysis was conducted on the study plans of the Master’s Degree courses on History teaching (MDHTs) offered by higher education institutions in Portugal, focusing specifically on the area of Training in Specific Didactics (TSD) and Initiation to Pedagogical Practice (IPP) for a more accurate characterisation of History teacher training at a national level (Table 1).

Even though all universities that train History teachers have opted for the same number of credits for TSD (although slightly higher at the University of Coimbra [UC]), it appears that the University of Porto (UP) offers a greater diversity of Curricular Units (5 CUs granting 6 credits) in the area of Training in Specific Didactics (TSD), followed by the University of Coimbra (4CUs) and UM, UL, and UNL with the least Curricular Units (3) concentrating the highest number of credits. It should be noted that all universities have opted for the designation ‘Didactics’ for History or Social Sciences, as is the case of UL, and only the University of Minho has opted for the designation ‘History Teaching Methodology’, with a strong focus on Historical Education and on Social Constructivism, adopting the Anglo-Saxon line of research on the teaching of History, followed for over 40 years of training, a formative trend that has been gradually affirming itself also at other Portuguese universities.

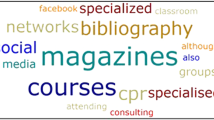

The analysis of the above programmes of Curricular Units of History Teaching ‘Didactics’ or ‘Methodology’ was based on the categories proposed by Gago (2018a). The articulation between the epistemology of History and Historical Education is present in four of the programmes (UP, UM; UC, UNL). One of the cross-cutting concerns seems to be the formative value of History, explicit at UP, UM, and UC. In pedagogical terms, all programmes seem to show some concern with preparing teachers for lesson planning, content selection, discourse in the classroom and historical questioning, design and construction of various didactic-pedagogical resources, although according to different epistemological-educational methods. There is also a concern to provide knowledge of the legal framework applicable to the educational system, the programmes and the various normative references, as well as the profile of the History teacher. In terms of bibliographic indicators, there is a clear integration of works on teaching methodology and didactics, with an indication of works of a general nature, as well as works in the area of the curriculum and on the formative value of History. It is noted that research studies on situated cognition, whether Portuguese or foreign, are present in all programmes. Although they are only incidental in some programmes (UL, UC, UNL), in others there is, effectively, an articulation between the epistemological and methodological dimensions of History (UM). The University of Porto (UP) even offers a Course Unit called (Perspectives in Historical Education).

Research methodology employed in the study

The objective of the study, shared in this article, is to map the historical and professional identity of future History teachers in Portugal, and to understand whether there are significant differences among these future History teachers that may be the result of different personal contexts and different approaches in terms of academic training, about what is most relevant in a History class, the purpose of a History teacher and what it means to be historically competent, as well as in terms of the symbols that can represent their identity, the abbreviated narratives of the History of Portugal and the use of ‘Us’ or ‘the Portuguese’ in History class.

Study design

In order to achieve the aforementioned objective, a mixed methodological design was adopted (Gorard and Taylor, 2004; Johnson et al. 2007), which allows addressing more complex research questions using a combination of traditional methods, the so-called ‘qualitative’ and ‘quantitative’ methods, within the scope of the so-called ‘non-experimental methods’. It was decided that this study would depart from a qualitative and longitudinal framework (Yin, 1994) which consisted of the application of an open questionnaire to 20 students attending the Master’s Degree in History Teaching at University of Minho (UM), at the beginning and end of the 2018–2019 academic year. The students were followed up in the CUs of History Teaching Methodology I and II. The data collected were analysed inductively and categorised using a method of systematic comparison, which involves a coding step that is divided into three phases: open coding, in which the questions posed to the data concern their nature and meaning, broken down into units of meaning, to which a name or code was assigned, thus giving rise to concepts; axial coding, in which the concepts are reorganised around an axis and the relationships between categories are defined, going beyond their characteristics and dimensions; and selective coding, which promotes the integration of the data around an explanatory central concept and highlights the category with the greatest potential to relate to all others, leading to the definition of the central category (Corbin and Strauss, 2008). Subsequently, based on the analysis of the data from the open questionnaire (Gago, 2020), a closed questionnaire was developed. The quantitative descriptive and inferential analysis of the collected data was conducted using the software IBM-SPSS 26. Several international research studies on History education have insisted on the complementarity of quantitative and qualitative methods (Barca, 2005; Barton, 2012; Gago, 2018a, 2018b; Grant, 2001; Gómez and Miralles, 2015; Solé, 2019).

Study participants—population and sample

The participants of the baseline qualitative framework of this study were 20 students from the University of Minho who attended the CUs History Teaching Methodology I and II in the academic year 2018–2019, as part of the Master’s Degree in History Teaching, which fits into convenience or accidental sampling (Cohen et al., 2001). The students were given an open questionnaire at the beginning of their training and subsequently at the end of their training, in a longitudinal perspective, in order to understand whether or not conceptual change took place. Subsequently, in May of 2020, based on the data collected and qualitatively analysed, a closed questionnaire was designed and applied, through the following link https://en.surveymonkey.com/r/89PSW7Q, to students of the Master’s Degree in History Teaching in the 3rd Cycle of Basic Education and in Secondary Education (MDHT) offered by the five universities that train History teachers in Portugal, the University of Porto (UP), University of Minho (UM), University of Coimbra (UC), University of Lisbon (UL) and NOVA University of Lisbon (UNL). The sample is non-probabilistic and was collected purposefully. From a universe of 173 students who attended the Master’s Degree course in History Teaching in the academic year 2019–2020, 52 responses were obtained, which corresponds to 30% of the population (Table 2).

Below is a more specific characterisation of the quantitative study sample. In terms of gender, the sample includes 28 male students and 24 female students, i.e., 53.8 and 46.2% of the sample, respectively. In terms of which year of the Master’s degree course students were in, 27 students were attending the 2nd year and 25 students were attending the 1st year of the programme, i.e., 51.9 and 48.1% of the sample, respectively. Most students (40) are aged between 21 and 30, which corresponds to 76.9% of the sample; 10 students are between 31 and 40 years old (19.2% of the sample) and two students are between 41 and 50 years old, representing 3.8% of the sample (Fig. 2).

Data collection instruments

The technique used for data collection was the survey and two instruments were prepared, an open questionnaire and a closed questionnaire. The open-answer questionnaire was only applied to students of the Master’s Degree in History Teaching of the University of Minho. It was answered in writing and administered at the beginning of the training of future history teachers and at the end of the same training course. The questionnaire contained the following questions:

At the beginning of this journey, it is important to reflect on a few aspects related to your professional growth.

-

1.

Please describe your idea of

-

a.

What a History class should be like.

-

A.

a ‘thing’ that you expect your students will learn from your History lessons.

-

a.

-

2.

What is thinking historically?

-

3.

What is your purpose as a History teacher? (Gago, 2018b, p. 511).

Twenty answers were obtained in the initial and final questionnaires. Based on the inductive analysis of the qualitative data, in line with Grounded Theory (Corbin and Strauss, 2008), a closed-answer questionnaire, consisting of 6 questions, was prepared, with items that were to be ranked in order of importance (6 being the most important and 1 the less important). One of the items would have to be excluded, with justification. The proposed questionnaire contained the following questions:

-

1.

History class must…

-

2.

The purpose of being a history teacher is…

-

3.

To think historically is…

-

4.

The symbols that reflect my identity are:

-

5.

The abbreviated narratives with the most significance for the History of Portugal are:

-

6.

In the classroom, it is more appropriate to say…

-

A.

‘The Portuguese gave new worlds to the world’

-

B.

‘We gave new worlds to the world’

Please justify your choice

-

A.

Analysis of quantitative data

The data collected in the closed-answer questionnaire was analysed in a descriptive and inferential way. It should be noted that, given the sample number and its dispersion, the inferential analysis will focus on the independent variables gender and year of master study.

Thus, the first question ‘History Class must…’, where respondents were asked to rank the options given, it was found that option A. (‘… be active and based on an interactive dialogue between the teacher and the students.’) was given a mean score of 4.52, that 50% of students placed it at 5 (median), and that the most frequent score was 5 (mode). It was followed by options C (‘… equally articulate knowledge and historical thought’), with a mean score of 3.94, G. (‘… take into account the starting and ending point of students’ learning.’) and B. (‘… employ several pedagogical resources and strategies that can motivate students.’) with an average importance of 3.13 and 3.10, respectively. The options that were given the lowest average score were options E. (‘… be based, first and foremost, on the mastery of historical knowledge.’) and F. (‘… foster a sense of citizenship in students.’). These two options were those most often excluded, as they present a statistical mode of 0. At the opposite end, we have option G. (‘… take into account the starting and ending point of students’ learning.’), for which the most frequent score was the maximum, i.e., 6. Below are the mean values, the median and the mode for the scores given to each of the answer options to question 1 (Table 3).

The second question inquired about the purpose of being a History teacher. It was observed that option B. (‘… is to increase students’ interest in History.’) was given a mean score of 3.73, that 50% of students ranked it at 4 (median), and the most frequent valuation was 4 (mode). The most frequent score given for option C. (‘… to develop active citizens.’) was the highest (mode of 6) and at the opposite end, we have options G. (‘… to provide diverse, current and fun resources and strategies.’) and F. (‘… to foster the development of the students’ identity with knowledge of the past.’) who also had the lowest average scores, 1.81 and 2.67, respectively (Table 4).

The mean scores given by students from the various universities to each of the options to the second question provides data that is noteworthy due to its diversity. It was observed that students from the University of Coimbra found option D to be the most important; students from the Universities of Lisbon and Porto considered option C took precedence; students from the University of Minho preferred option E, and students from the Nova University of Lisbon went for option A (Table 5).

Regarding the third question ‘To think historically is…’. It was observed that option E. (‘… to understand historical processes – change and permanence.’) was given a mean score of 4.27, that 50% of students ranked it at 5 (median), and the most frequent valuation was 5 (mode). Answer option B. (‘… to have a reference, a heritage, a common legacy that is useful for the present’) was given a mean score of 1.62, 50% of students gave it a score of 1 and it was the option most often excluded. The option most frequently excluded was option C. (‘… to use lessons and examples from the past when making decisions.’ (Table 6).

In terms of understanding the historical identity of future history teachers, more specifically the questions related to historical identity, a second set of questions was proposed.

Thus, in Question 4, students were asked to rank 8 identity symbols, from 7 (most important) to 1 (least important), and to exclude one of them. These identity symbols were selected based on Pais (1999), the Portuguese coordinator of the European Youth & History (Angvikand and Von Borries, 1997) and Sobral and Vala (2007), Portuguese coordinators in the International Social Survey Programme. Considering the study and the conclusions of Pais (1999), it seems that Portuguese adolescents demonstrate, in a tenuous way, a “supra-national and European” identity, when they think of colonialism as an adventure and artificially feed a myth, as well as national pride. Sobral and Vala (2007) point out that pride in the past is due, in part, to school education and its unending insistence on teaching about maritime expansion/the Discoveries. The present sentiment among the Portuguese seems to pass for an uncritical pride of their past. Fascination with the past can be an escape from present disillusionment, but it can also be a means of substantiating, valuing, and legitimising present behaviour, denouncing an apparent lack of concern for systematic questioning. It might also seem that Portuguese adolescents share an uncritical logic of adopting and not adapting historical knowledge to a changing and diverse reality.

Thus, through the analysis of the data obtained, we can consider that the symbol that is most frequently considered to symbolise the identity of future History teachers is ‘Language’, with a mean score of 6.27, a median of 7 and a mode of 7. It is followed by options ‘The flag’ and ‘The red carnation’ with mean scores of 4.44 and 4.06, respectively. It should be noted that the most frequent score given to this latter identity symbol is 6. The option ‘Portuguese stew with cod’ was given a mean score of 1.42, and it was also the one most frequently excluded. The option ‘Port wine’ received a mean score of 2.23 and the ‘The caravel ship’ 2.60 (Table 7).

In view of the goal of mapping the historical identity(ies) of future History teachers, students were asked to rank the abbreviated narratives that are most significant for the History of Portugal (question 5), from 7 (most important) to 1 (least important), and to exclude one of them. In terms of abbreviated narratives for the History of Portugal, on average, Portuguese MDHT students considered that the most important one was that of the Revolution of 25 April, which was given a median score of 6 and a mode score of 7 (the highest score). It was followed by the abbreviated narrative ‘King Afonso Henriques’, which got an average score of 4.88 and a mode of 7. The least valued abbreviated narrative, in mean terms, is that of ‘King Sebastian’, with an average score of 1.85 out of 7. It should be noted that the abbreviated narrative ‘King Sebastian’ had a mode score of 0 Table 8.

Regarding the question ‘In History class, should we use the term “we” or “the Portuguese”?’, the majority of students (80.8%) believe that the term ‘the Portuguese’ is the most appropriate, in contrast to 19.2%, who prefer ‘we’.

Taking into account the sample number and its dispersion, a statistical test aimed at comparing proportions was carried out, with a significance level of 5%, to assess the possibility of statistically significant differences between the variables that are independent of gender and year of study with the remaining data under study.

In terms of hypothesis testing, taking into account the differences between the size of the universities participants, only the variables gender and year of master study were considered, due to the fact that the two groups to which they relate have similar sizes. Thus, taking into account the nature of the variables, the Kruskal–Wallis non-parametric test was used to test whether there were differences in distribution between the two groups that make up the variables ‘year of study’ (1st or 2nd year of the Master’s Degree) and gender (female or male), with a 5% significance level. Thus, the students rank of scores to all questions were tested, considering their gender and the year of the Master’s Degree they attended. We present below the results of the tests that demonstrated the occurrence of statistically significant differences.

Regarding the students rank of scores of the various options for answers to the first question (‘History Class must…’, there were statistically significant differences in the rank of scores given to option B. (‘… employ several pedagogical resources and strategies that can motivate students.’) depending on the year of the Master’s Degree that the students attended (Table 9).

To better understand this difference in distribution, a contingency table (Table 10) was created, which combines the different rank of scores for this answer and the Master’s Degree year attended by the students.

As shown in Table 10, 1st year students place this option at a central point but attribute it tendentially lower importance, i.e., the most frequent valuations are ‘Less important’, ‘Somewhat Important’ and ‘Important’, ordered according to decreasing frequency, all together totalling 18 answers from students. Students in the 2nd year, on the other hand, present a more heterogeneous distribution among the various options, but tend to value it more, as the most frequent valuation option is ‘Very Important’, chosen by 7 students, and the options ‘Extremely Important’, ‘Important’ and ‘Somewhat Important’ account for a total of 12 answers from students.

Next, an analysis was conducted on the distribution of the options selected by students of the 1st and 2nd years of the Master’s Degree and on the rank of scoring of the identity symbols (Table 11).

It was found that there were statistically significant differences between the options chosen by students in each of the two years of the Master’s Degree for the identity symbols ‘Flag’ and ‘Language’. In order to better understand these differences, contingency Tables 12 and 13 were prepared.

As shown in Table 12, the valuation most frequently given by students attending the 1st year of the Master’s Degree to the identity symbol “Flag” was ‘More Important’ and their choices fell mostly in the lowest levels of importance. On the other hand, students attending the 2nd year of the Master’s Degree, were more frequently inclined to consider this symbol ‘Very Important’, but their choices fell mostly on the highest levels, i.e., ‘More Important’, ‘Very Important’ and ‘Extremely Important’. Regarding the identity symbol ‘Language’ (Table 13), most students of the 2nd year of the Master’s Degree considered it ‘Extremely Important’ and none considered it to be ‘Less Important’, ‘Somewhat Important’ or ‘Important’, in contrast with the choices of students of the 1st year, which were distributed across all the options, except exclusion.

The same non-parametric test was used to check for statistically significant differences between the choices made by males and females regarding the valuation of the identity symbol ‘Portuguese stew with cod’, as shown in Table 14.

Given the result obtained, an analysis was made to try to understand how the choices made regarding this identity symbol differed between the two genders of the students who participated in the study. The aim was, thus, to understand, in descriptive terms, how the scores given to the identity symbol ‘Portuguese stew with cod’ was distributed between the two gender groups (female and male). The data was intersected and Table 15 was constructed, which allows us to observe that the majority of female students have either excluded this symbol of identity or attributed it a lower level of importance, in contrast with male students, who gave this symbol of identity different degrees of importance.

Tests were also conducted to check for statistically significant differences in the distribution between genders concerning the valuation attributed to the abbreviated narratives of the History of Portugal. It was found that there were differences in the valuations given to abbreviated narrative ‘Revolution of 25 April 1974–Democratic Revolution, end of dictatorship’ between the two genres, as shown in Table 16.

In order to understand the differences in the valuation of this abbreviated narrative of the History of Portugal by gender of participating students, we observed the differences in the valuation of this abbreviated narrative by students (Table 17).

As shown in the previous chart, male participants value this abbreviated narrative mostly as ‘Extremely Important’, while most female students considered it ‘Important’. It should also be noted that none of the female students have excluded this abbreviated narrative.

Discussion and conclusions

To conclude, and synthesising the results obtained, we can find differences in relation to the professional and historical identity of future History teachers in Portugal. These differences, found among respondents from the various higher education institutions, are evident in the frequencies and percentages indicated, and can be, to some extent, justified by the contexts of academic training provided by the various institutions, as well as by the trainees’ personal characteristics.

Thus, in relation to the first question ‘History class must…’ it was found that great importance is attributed to the dynamics of the classroom, and that students value dialogue in the classroom between teacher and students, as well as the articulation between historical knowledge and historical thought, with a focus on students, taking into account prior ideas at the points of departure and arrival of their learning process, but also on the pedagogical resources and strategies that motivate them. These results show that, in some higher education institutions (UM, UP, and UNL), these aspects are explicitly addressed by the syllabus of Curricular Units such as ‘Didactics of History’ or ‘History Teaching Methodology’. We are witnessing the emergence of a teacher training method that is centred on the social constructivist paradigm (Fosnot, 1996), which gives prominence to the role of the student in the learning process and to the role of the teacher as a guide and an organiser of challenging and problematising activities (Barca, 2004). On the other hand, it was observed that there are respondents, although in smaller numbers, who consider historical knowledge to be primordial in the classroom, and value the role of History class for the development of citizenship in students. We find these aspects more explicitly addressed in the programme of the University of Coimbra (UC), but also in those of the University of Porto (UP), albeit only in relation to the aspect of citizenship. Statistically significant differences were found between the students attending each of the two years of the Master’s Degree in the valuation attributed to the various options for answering Question 1. Students attending the 2nd year of the Master’s Degree attributed more value to option B. ‘… employ several pedagogical resources and strategies that can motivate students.’ than 1st year students. This may be related to their personal/professional concerns, as they had started having classroom teaching experience and, as such, they felt the need to respond to the demands of their daily work. Such a situation may indicate a stage of teaching professionalism guided by classroom management concerns, in line with a performance agenda, in which it is believed that everything can be resolved through efficient management.

As for the purpose of the History teacher (Question 2), the results point to a trend towards valuing the teacher’s contribution to increasing the students’ interest in History, which suggests a raising of awareness among trainees to the relevance of this disciplinary area in the curriculum and in the general training of students, but also towards the purpose of the History teacher as a promoter of respect for the past and heritage, as well as an instrument for the development of critical, active and interventive citizens. These choices seem to be in line with a professional identity that seems to centre its pedagogical-educational action around broad values and ideals of society. It should be noted that the presence of heritage and heritage education is evident in the programmes and bibliography proposed for the Curricular Unit at the Universities of Minho (UM), Porto (UP), and Coimbra (UC), which may explain this appreciation by part of the students of these universities. On the other hand, such a relationship is not apparent between the proposals of the programmes of the University of Porto (UP) and the high importance placed by students on the role of the teacher as a developer of active citizens, unlike what happens in the Universities of Minho (UM) and Coimbra (UC) in which this aspect, despite explicitly addressed by the course programmes, is chosen by few students. The more technical aspect of the teacher as a provider of diverse, current and fun resources and strategies to motivate students for the learning process appears as the least relevant for these future teachers, despite the fact that, in all the programmes analysed, there is a clear concern for the designing and construction of diverse teaching materials.

Regarding the third question ‘To think historically is…’, the data reveal a greater incidence of the association of historical thinking with the understanding of historical processes—change and permanence (E), the employing of critical thinking when ‘interpreting information’ (D), with knowing how to ask multiple questions that will lead to different answers and making decisions (F) and with explaining realities in a contextualised way and understanding multiple courses of action (G). From the selected options, it can be concluded that future teachers associate thinking historically with an intellectual, cognitive process, with a mental structure that allows understanding and making sense of the past, and employing historical knowledge in a critical way in order to solve problems (Lévesque, 2008). These results, namely the options most frequently chosen, reveal an internalisation of the epistemological principles of historical education on the part of trainees. In turn, the exclusion of options B and C indicate more traditional views of the purpose of History and of what it is to think historically. So, it appears that future History teachers seem to consider that history is transformative/transforming and that the development of their students’ historical thinking and knowledge can contribute to (a) more complex understanding(s) of the world (Lee, 2011). Thus, historical education can contribute to a historical awareness and identity that values dialogue and respect for Humanity’s diversity.

With regard to the historical identity of future History teachers looking at the choices made regarding the symbols that reflect the identity of future Portuguese History teachers, ‘Language’ appears as the most valued symbol, both on average and in terms of the most frequent valuation in the upper limit. Then come ‘The flag’ and ‘The red carnation’. The mean valuation of ‘The red carnation’ is inconsistent with the data presented by Gago (2018a), in which future History teachers and History teachers with several years of experience ranked as the third symbol of their identity not the ‘The red carnation’, but ‘The national anthem’, which appears here ranked as the fourth symbol of identity. It should be noted that, in Gago (2018a) ‘The red carnation’ came, on average, in sixth place out of eight. It should also be noted that there were statistically significant differences in the valuations of the symbols ‘Flag’ and ‘Language’ between the students of the two years of the Master’s Degree, with 1st year students valuing these symbols less than 2nd year students. Regarding the identity symbol ‘Portuguese stew with cod’, there are differences in the importance given by students of the two genders. Compared to male students, female students excluded this symbol more often or valued it less. The reasons for this difference will be looked into by the researchers in a follow up of this study.

Regarding the question associated with the most significant abbreviated narratives of the History of Portugal, in mean terms, future Portuguese History teachers, in line with what had happened with identity symbols, gave more importance to the abbreviated narrative ‘Revolution of 25 April’, followed by ‘King Afonso Henriques’ and ‘Discoveries’. These data are inconsistent with those presented by Gago (2018a), in which future History teachers and History teachers with varied teaching experiences ranked ‘King Afonso Henriques’ in the first place, but in line with those same data (Gago, 2018a) they continue to place less value on the abbreviated narratives that seem to approach certain national historical realities in a less positive way. However, it should be noted that the average ranking of abbreviated narratives ‘King Afonso Henriques’ and ‘Discoveries’ in second and third place, respectively, may also indicate a foundational historical consciousness and identity that seem to be indexed, given the depth and intensity of these abbreviated narratives, to a national esteem that attempts to highlight the proudest moments/processes of the past to the detriment of less positive moments. The abbreviated narrative ‘Revolution of 25 April’ showed statistically significant differences regarding the distribution of valuations given by students of each gender. Male students attributed it higher degrees of importance than female students. The reasons for this difference will be looked into by the researchers in a follow up of this study.

The data in this study are in line with Apostolidou and Solé (2019) about how Portuguese and Greek students and prospective teachers conceptualise their identity and historical identity. The prospective teachers would have to choose from a list of topics and facts which would be most appropriate to be taught to refugees coming to Portugal and Greece. Portuguese prospective teachers mostly selected the national history related to the beginning of nationality, the period of the Discoveries/maritime expansion, the Portuguese empire, and the Revolution of 25 April, topics that may, to some degree, evidence a nationalistic perspective of History and of the relevance of freedom. In contrast, Greek prospective teachers mostly selected topics related to the world and to the present experiences of refugees (the two World-Wars, Dictatorship, the 1821 Liberation War and the 1944–1949 Civil War). Greek students expressed themselves through the ‘Liberal and Cognitive’ and the ‘Empathy’ categories, while Portuguese students ranged more between the ‘liberal’ and ‘republican’ categories. In another study conducted by Apostolidou and Solé (2020) about National–European identity and notions of citizenship expressed by prospective teachers in Portugal and Greece, the findings show continuities with regard to national identity, and more specifically, ethnocentrism, as well as slight transitions in respect of perceptions of Europe and European identity.

As for the use of ‘We’ or ‘the Portuguese’, the future History teachers who participated in this study showed a greater tendency to use the term ‘the Portuguese’, which may be in line with a logic of concerns of respect towards the cultural diversity that they may find in their classrooms, similarly to what happened with the answers given by British history teachers in Gago (2018a).

The data suggest the existence of articulations between the thought and historical identity of future History teachers and their professional identity. It is concluded that there is an urgent need to rethink the curricula of higher education curricular units, as well as to ensure that the training of History teachers is in line with new demands in terms of the epistemology(ies) of History and Education, as well as of teacher training. A line of teacher training that promotes transformative professional growth, in line with a democratic professionalism that promotes challenges of varying degrees of complexity in the classroom, with a view to an understanding of the world, and that is supported on and fosters a historical conscience and identity that is guided by analysis and critical intervention, focusing on what unites us in diversity, i.e., respect for the diversity of Humanity.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during this study are not publicly available due to confidentiality reasons, but are available in a codified form from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Angvik M, Von Borries B (eds) (1997) Youth and History: a comparative European survey on historical consciousness and political attitudes among adolescents. Körber-Stiftung, Hamburg

Apostolidou E, Solé G (2019) Different ways to relate with the ‘other’: prospective teachers ideas about teaching history to refugee youth-a comparative study. In: Moreno-Vera JT, José Monteagudo JF (eds) Temas controvertidos en el aula. Enseñar historia en la era de la pósverdad. Editum, Editora de la Universidade de Múrcia, Múrcia, p 129–144

Apostolidou E, Solé G (2020) National–European identity and notions of citizenship: a comparative study between Portuguese and Greek university student teachers. History Educ Res J 17(1):81–98. https://doi.org/10.18546/HERJ.17.1.07

Barca I (2004) Aula Oficina em História: do Projecto à Avaliação. In: Barca I (eds) Para uma educação de qualidade: Atas das Quartas Jornadas de Educação Histórica. Braga, Centro de Investigação em Educação (CIED)/Instituto de Educação e Psicologia, Universidade do Minho, pp. 131–144

Barca I (2005) Till New Facts are Discovered: Students’ Ideas about Objectivity in History. In: Ashby R, Gordon P, Lee P (eds) International Review of History Education, Vol. 4: Understanding History: Recent Research in History Education. Routledge- Farmer, Nueva York, p 68–82

Barton K (2012) Applied research: educational research as a way of seeing. The Professional Teaching of History: UK and Dutch Perspective. In: MacCully A Mills G, Boxtel C (eds) Coleraine: History Teacher Education Network, 1-15.

Cohen L, Manion L, Morrisson K (2001) Research methods in education (5th edn.). Routledge/Falmer, London and New York

Corbin J, Strauss A (2008) Basics of qualitative research. Techniques and procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA

Fosnot C (1996) Construtivismo e Educação: Teoria, Perspectivas e Prática. Instituto Piaget, Lisboa

Flores M A (2012) Teachers’ work and lives: a European perspective. In: Day C (eds). The Routledge international handbook of teacher and school development. Routledge, London, pp. 94–107

Flores MA (2011) Tendências e tensões no trabalho docente: reflexões a partir da voz dos professores. Perspectiva 29(1):161–191

Korthagen F (2003) Practice, theory and person in life-long professional learning. Paper presented at ISATT Conference. Leiden: [s. n.].

Korthagen F, Vasalos A (2005) Levels in reflection: core reflection as a means to enhance professional growth. Teachers Teaching 11(1):47–71

Gago M (2018a) Consciência Histórica e Narrativa na aula de História. CITCEM-FLUP. Santa Maria da Feira, Edições Afrontamento

Gago M (2018b) Ser professor de história em tempos difíceis: início de um processo formativo. Antíteses 11(22):505–515

Gago M (2020) A aula oficina na caminhada de aprender a ser professor de história. Roteiros 45:1–18. https://doi.org/10.18593/r.v45i0.21736

Gómez C, Miralles P (2015) Pensar historicamente o memorizar el Pasado? Revista de Estudios Sociales 52:52–68

Gorard S, Taylor C (2004) Combining Methods in Educational and Social Research. Open University Press, UK

Johnson RB, Onwuegbuzie AJ, Turner LA (2007) Toward a definition of mixed methods research. J Mixed Methods Res 1(2):112–133

Lee P (2011) Historical literacy and transformative history. In: Perikleous L, Shemilt D (eds) The future of the past. UNDP-ACT, Cyprus, p 129–168

Lévesque S (2008) Thinking historically: educating students for the twenty-first century. University of Toronto Press, Toronto

Melo MC (2015) A formação de professores de História em Portugal: práticas pedagógicas e investigativas. Revista História Hoje 4(7):41–61

Pais JM (1999) Consciência Histórica e Identidade. Os jovens portugueses num contexto europeu. Celta Editora, Oeiras

Rüsen J (2001) What is historical consciousness? A theoretical approach to empirical evidence. Paper presented at Canadian Historical Consciousness in an International Context: Theoretical Frameworks. University of British Columbia, Vancouver

Sachs J, Mockler N (2012) Performance cultures of teaching: threat or opportunity. In: Day C (org.). The Routledge international handbook of teacher and school Development. London: Routledge, pp. 33–43

Schmidt MA (2016) Interculturalidade, humanismo e educação histórica: formação da consciência histórica é mais do que literacia histórica? In: Schmidt MA, Fronza M (eds). Consciência histórica e interculturalidade: investigações em educação histórica. Curitiba: W. A. Editores, pp. 21–33

Sobral J, Vala J (2007) Povo nostálgico-Portugueses estão agarrados ao passado e descontentes com o presente” In Agência Lusa (28 of February 2007).

Solé G (2019) Children’s understanding of time: a study in a primary history classroom. History Educ Res J 16(1):156–171

Vieira F et al. (2013) O papel da investigação na prática pedagógica dos mestrados em ensino. In: Silva B et al. (orgs). Atas do XII Congresso Internacional Galego-Português de Psicopedagogia. Braga: CIEd, Universidade do Minho, pp. 2641–2655

Yin R (1994) Case Study Research: design and methods (2nd edn.). SAGE Publications, Thousand Oaks

Acknowledgements

This work is funded by CIEd—Research Centre on Education, Institute of Education, University of Minho, projects UIDB/01661/2020 and UIDP/01661/2020, through national funds of FCT/MCTES-PT. This research was funded by the “Spanish Ministry for Science, Innovation and Universities. Secretary of State for Universities, Research, Development and Innovation”, grant number PGC2018-094491-B-C33 (MCI/AEI/FEDER, UE), and “Seneca Foundation. Regional Agency for Science and Technology”, grant number 20874/PI/18.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Solé, G., Gago, M. The history teacher education process in Portugal: a mixed method study about professionalism development. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 8, 51 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-021-00726-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-021-00726-9