This article discusses the evolution and main characteristics of Delphi’s statuary landscape, focussing on the process of ‘prestige spatialisation’ via the erection of honorific portraits within the territory of Delphi. This survey of inscribed decrees and honorific inscriptions accompanying Delphic statues aims to present trends and tendencies in the placement of honorific statues at Delphi from the mid-fifth century b.c. to the late fourth century a.d. Furthermore, it seeks to illuminate connections between power, space, and memory in the Delphic temenos. In the following sections, I will argue that the placement of honorific statues within the Delphic temenos was not a random act but in fact a precisely planned process which was influenced by several (variable) factors. These factors included the availability of space, the visibility of the monuments, proper neighbourhood, and the number of visitors that could be expected. Scott has interpreted the fifth-century b.c. habit of placing honorific statues and monuments at the most conspicuous Delphic locations as an attempt to ideologically monopolise sanctuary space and to assert one’s domination over the sanctuary.Footnote 1 Concurring with this interpretation, I argue that it also holds true for the time of Aetolian domination over Delphi (third century b.c.). My article places particular emphasis on Delphic relations with the Aetolian League, dealing with questions regarding the nature of Aetolian self-representation at Delphi. The Aetolian presence at Delphi has, of course, already been widely discussed.Footnote 2 My analysis, however, offers a new perspective on this issue by contrasting Delphi with Thermos to assess the degree to which Aetolian statues and monuments dominated the sacred space at Delphi and the manner in which they represented their donors to internal and external audiences.

The statuescape of Delphi consisted of multiplied nodes, each of which continually evolved: new monuments rose beside or even in front of older ones, shifting across time the perspectives of spectators.Footnote 3 The original Delphic agora might have held statues of the greatest value to the city itself but, regrettably, remains unexcavated.Footnote 4 The so-called Roman agora came into being under Hadrian. However, it did not house any imperial statues before the mid-fourth century a.d. Footnote 5 The Panhellenic sanctuary of Apollo comprises the most significant statuary space within the polis and is, accordingly, given the greatest attention in this article.

A person less familiar with Greek statues might, perhaps, expect that this paper discusses three-dimensional honorific portraits from Delphi. Unfortunately, however, hardly any of the honorific statues from Delphi have survived. Made from valuable (and therefore recyclable) bronze, the statues were stolen or melted down in times of military or economic need, from the ancient times onwards to this day.Footnote 6 Nonetheless, although the statues themselves have been lost, the inscriptions on their bases, literary accounts, and thirty-three surviving public decrees still make it possible to study the long-gone portraits.

The first of the factors which impacted upon the number, types, and location of preserved statues is the fact that Delphi was different from other Panhellenic sanctuaries: neither Olympia, Nemea, nor Isthmia were in direct contact with a permanent settlement possessing its own political institutions. Many aspects of Delphic civic life took place within the temenos, with the bouleuterion and prytaneion located within the peribolos.Footnote 7 The exact relation between the sanctuary and the polis remains difficult to determine, since Delphi was indiscriminately called a polis both in the urbanFootnote 8 and the political senses.Footnote 9 The second factor concerns the history of the site after the fourth century a.d. From the fifth century a.d. onwards, the Delphic sanctuary was turned into a prosperous urban centre, a fate the former Roman agora escaped.Footnote 10 The urban development at the sanctuary proved to be short-lived, with the site already abandoned in the early seventh century.Footnote 11

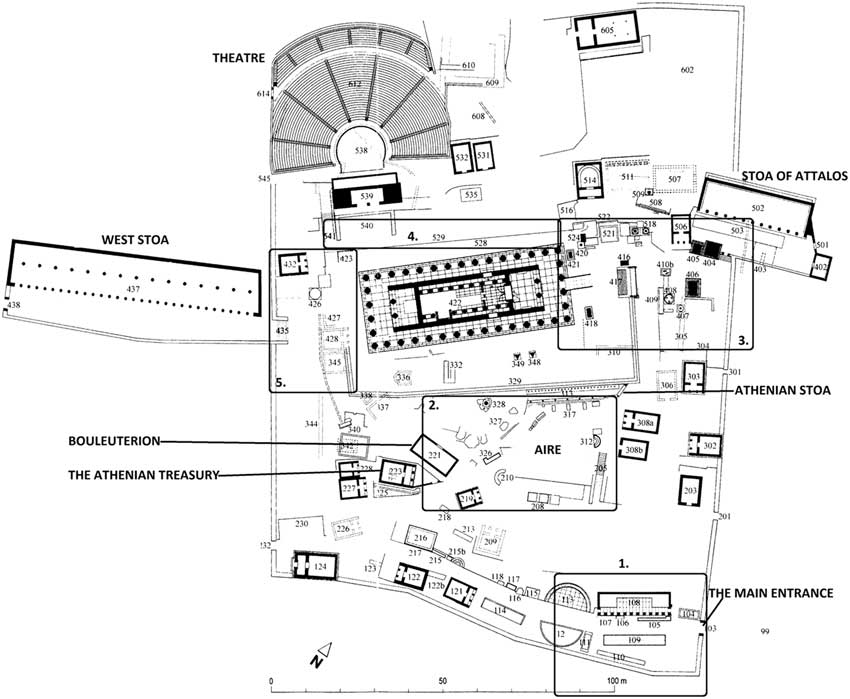

Before I proceed to the core of my argument, it must be stressed that scholars interested in honorific culture of Hellenistic and Roman Delphi encounter difficulties unknown to those studying the Archaic and Classical dedications. The primary problem is the paucity of both secondary literature and ancient sources. While Archaic and Classical offerings in Delphi have been discussed comprehensively by Vatin, Jacquemin, Partida, Scott, Schörner, and Krumeich, Hellenistic and Roman honorific statues and the intricacies of their erection have received less attention by modern scholars.Footnote 12 As for the ancient sources, Pausanias’ Description of Greece strongly emphasises pre-Hellenistic artworks and votive offerings but omits, for some unspecified reason, all statues related to athletic victors from Delphi.Footnote 13 Moreover, literary sources that refer to pre-Hellenistic monuments commonly locate these dedications very precisely. The post-Classical evidence is epigraphic and epigraphic material poses certain challenges. Firstly, many post-Classical statue bases have been moved, recycled, or re-inscribed over time, i.e. their original sites are lost to the vagaries of time.Footnote 14 Pieces of broken inscriptions have turned up in several locations, all of them feasible as original location sites.Footnote 15 Furthermore, certain post-Classical texts have come to us in the form of outlines or unfinished drafts, generally unconnected to a particular site.Footnote 16 Finally, although the archaeological investigation at Delphi began over a century ago, the ancient part of the site has never been fully excavated, much less published. The locations of Delphi’s necropoleis and agora remain unknown, with tombstones, statue bases, and decrees awaiting discovery. What is more, a backlog of two volumes has built up in the publication of Delphic inscriptions.Footnote 17 Due to these factors, neither the statuary landscape of Delphi nor the site chronology can be described with any precision.Footnote 18 Consequently, the sections which follow will focus on general trends and most important locations for the practice of honorific portraiture in Delphi rather than analyses of detail. (Figures 1-3)

Fig. 1 Map of the sanctuary at Delphi. (The plans and maps used in this article are after Guide [2015] ‘Planche V’ and Atlas [1975] ‘Planche III’, with modifications and adjustments made by the author.)

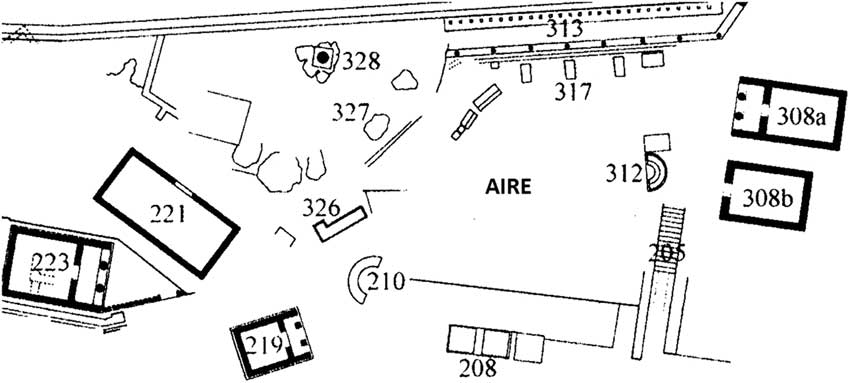

Fig. 2 The region between the Athenian Treasury (no. 223) and the Athenian Stoa (no. 313)

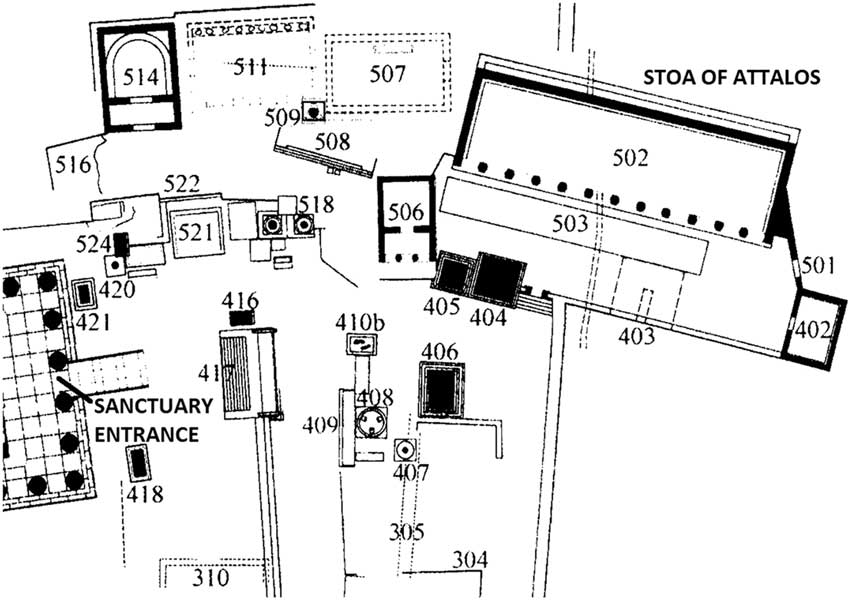

Fig. 3 The eastern side of the sanctuary

The Beginning of the Sacred Way

In the sixth century b.c., a main entrance to the sanctuary was built in the south-eastern section (Fig. 1).Footnote 19 Although, over time, seven other entryways were built at each of the terracing levels, the south-eastern entrance remained the principal gate. Accessed annually by thousands of visitors, the main gate was initially ipso facto the most appealing site for the display of honorific statues. Which polis dominated the entrance site with its statues and inscriptions varied across time. After the battle of Marathon, the citizens of Athens placed an image of Miltiades near the entryway, which, together with other Athenian dedications, including the treasury and stoa, exemplified the control Athens had over Delphi in the late sixth and early fifth century b.c. Footnote 20 By the early fourth century, Miltiades’ statue stood in the shade of numerous subsequent Lacedaemonian votive offerings, two rows of thirty-eight statues in total, with Lysander’s portrait up frontFootnote 21 , followed by Lysander’s allies from Aegospotami.Footnote 22 The Spartans did not enjoy their visual domination of the sanctuary’s entrance for long either. In 369 b.c., the Arcadians commemorated their victory over the Lacedaemonians by dedicating an imposing statue which overshadowed the entrance to the Spartan stoa.Footnote 23

The aforementioned examples prove that, in the Classical period, the beginning of the Sacred Way came to be viewed as an excellent showground for the Greek states to display their glorious history. It became a story board that flaunted the power of the current Greek hegemon and retold the past from a carefully edited perspective to any pilgrim who visited the site. Archaeological excavations have unearthed a number of much younger honorific statues in this area, including representations of Theopompos of KnidosFootnote 24 and C. Lentulus, a Roman quaestor.Footnote 25 The erection of random statues reflects the decline of that space’s prestige over the centuries, in favour of other spots further up the Sacred Way and closer to the temple.

The Region between the Athenian Treasury and the Athenian Stoa

Another great statue gallery followed the Sacred Way from the Athenian treasury (no. 223) and bouleuterion (no. 221)Footnote 26 up to the Athenian portico (no. 313), the oldest stoa at Delphi (Fig. 2).Footnote 27 The prestige of this region came from its physical prominence (which made locally erected statues particularly conspicuous) and the importance of monuments located along the polygonal wall, such as the renowned Sibyl rock (no. 326) and the Sphinx of Naxos (no. 328). A superb piece of architectural ingenuity, the aforementioned treasury of the Athenians served as a gallery for spolia looted from the PersiansFootnote 28 , while the open space between the treasury and the Athenian portico (called the aire) provided the ground for many of Delphi’s festivals and ritual processions.Footnote 29 The spacious lot around the aire quickly filled up with honorific monuments and sprawling exedrae.Footnote 30 The most prominent exedra was that of Herodes Atticus and his family. The Delphic polis honoured the great benefactor of Greece and his son with two statuesFootnote 31 and Atticus himself dedicated five portraits of his wife and offspring which probably stood in the family exedra.Footnote 32 An excellent showground, the aire contained a bewildering variety of other honorific monuments. For example, it housed images of (a) Ptolemaios II and Arsinoe (set up by the famous constructor of the lighthouse of Alexandria),Footnote 33 (b) Marcus Claudius Marcellus (Delphi’s patron, honoured by the grateful community),Footnote 34 (c) Titus Avidius Quietus (the proconsul of Achaea, honoured by the Amphictyony),Footnote 35 and (d) a statue base of an unknown Roman legatus, found near the Sibyl rock.Footnote 36 The conspicuous Athenian presence noticeable around the aire in the fifth century b.c. eventually gave way to more prominent portraits of Hellenistic monarchs and high-ranking Roman officials, highlighting the ongoing spatial value of this area.Footnote 37

The East Side of the Temple: ἐπιφανέστατος τόπος

The east-facing temple entrance constituted the centre of Delphi (Fig. 3): regardless of their chosen entryway, all visitors had to pass through the eastern terrace to reach their final destination, the temple of Apollo. The eastern temple terrace was awash with a plethora of statues of deities, dating to the Archaic and Classical periods, gold and silver tripods, the magnificent serpent column of Plataea, the Athenian palm tree dedication, as well as booties won from the Persians.Footnote 38 Effective as a display ground, the eastern terrace encompassed a chresmographeion, an area for pilgrims to gaze at the offerings while awaiting their turn.Footnote 39 In the later period, the display area was known for its profusion of imperial letters addressed to Delphians, engraved upon the orthostates built into the southern cella wall of the temple of Apollo.Footnote 40

The eastern side of the temple housed one of the most famous dedications and honorific monuments that marked the most eminent spot at Delphi. Krumeich mentions several epiphanestatoi topoi located at Delphi.Footnote 41 The preserved honorific decrees leave no doubt that the temple terrace was the most eminent and coveted spot in the Delphic sanctuary.Footnote 42 Out of thirty-three decrees granting honorific statues, six contain the phrase ἐπιφανεστάτωι τοῦ ἱεροῦ τόπῳ.Footnote 43 The decree issued for Nikomedes III, the king of Bithynia, reads [ἀν]αγρ[ά]ψαιδὲ τὸ ψάφισμα τοὺς ἄρχοντα[ς τοὺ]ς ἐν[άρχους ἐν τῶι ἐπιφανεστάτωι τοῦ ἱεροῦ] τόπῳ ἐπ[ὶ τ]ὰν βά[σιν τ]οῦ πάπ<π>ου αὐτῶν Προυσί[α].Footnote 44 The monument of Prusias (no. 524), into which the inscription was carved, stood at the north-eastern side of the temple’s entrance, next to the temple terrace. A document of c. 104 b.c. also depicts the eastern terrace as Delphi’s top honorific place.Footnote 45 The text prescribes the most eminent setting for its inscription and, indeed, the Aemilius Paulus pillar (no. 418) bearing the inscription boarders the south-eastern fringe of the temple’s terrace.Footnote 46

Excavators of the eastern section of the temple have unearthed numerous bases of statues which once embellished the terrace. Entrants to the temple are said to have been welcomed by a portrait of Homer.Footnote 47 Likewise, the Delphic terrace supposedly contained the gilt image of the famous sophist Gorgias.Footnote 48 Other Classical characters immortalised on the eastern terrace included the Spartan king Archidamos and Philip II of Macedon. Later offering also dotted the region. During the Aetolian domination over Delphi, the Epirotan princess Nereis dedicated a family group statue.Footnote 49 Similarly, the Amphictyony voted at least seven statues to the Chian hieromnemones, which are known to have originally stood near the Chian altar (no. 417).Footnote 50

A significant change took place between 241-226 b.c., when the Amphictyony gave the Attalid kings permission to break the eastern boundary wall of the Apollo sanctuary at the level of the temple terrace and to raise their own stoa. The newly constructed portico abutted a terracing wall, setting aside a large courtyard space for honorific monuments, where pillars of Attalos I (no. 404) and Eumenes II (no. 405) were located.Footnote 51 This development demonstrates beyond any doubt that the temple terrace held such appeal as a display space that it was better to break the walls and get a spot in here than below. To prevent overcrowding, the Amphictyony issued a law in 223-222 b.c. stressing that ‘no other dedications were to be put within the Attalid stoa complex except those from the Attalids themselves’.Footnote 52 The decree ceded to the Attalids, the great Delphic benefactors of the late Hellenistic period, a complete monopoly on the space contiguous to their extraordinary building, thus guaranteeing that the Attalid monument would never be overshadowed by the dedications of others.

Monuments to Romans made their first appearance on the eastern terrace in 169 b.c., when Aemilius Paulus adopted the base of Perseus’ statue for his own image.Footnote 53 The temple terrace came to resemble a Julio-Claudian family gallery, its eastern boarder boasting the bases of statues of Augustus’ grandchildrenFootnote 54 , a portrait of Drusilla set up by the pronaos on top of the high columnFootnote 55 , as well as an image of Nero.Footnote 56 Among statues of the later emperors, we find an image of Nerva set up by the Delphic polis Footnote 57 and the so-called Emperor’s Monument (no. 421), believed to represent Domitian.Footnote 58 However, the Delphic ἐπιφανέστατος τόπος did not exclusively contain statues of the members of the imperial family. The citizens of Delphi also commissioned an honorific portrait for Gaius Publicius Proculeianus, the primipilaris and procurator of Pannonia and AchaeaFootnote 59 and voted (jointly with the Amphictyony) an image to an uncertain Roman consul.Footnote 60

The visibility of honorific monuments set up within the Delphic temenos can be ascertained from the eyewitness accounts of Plutarch and Pausanias, supplemented by the preserved archaeological and epigraphical material. In the early Hellenistic period, the sanctuary must already have been overcrowded with monuments, statues, treasuries, and other buildings. Many of these constructions were covered in inscriptions. An over-stimulated visitor would not have lingered over each and every text or statue but would instead have focussed on only the most prominent monuments, a circumstance which, in turn, would have made benefactors compete with one another. In other words, a competition for height and monumentality, and thus visibility, began. Krumeich noticed that the proportion of pillars and columns is much higher in Delphi than in Olympia. Moreover, the integration of portraits in groups is a characteristic feature of the Delphic statuescape.Footnote 61 The most coveted spots lay clustered along most-frequented routes, aligned with treasuries and other focal points. The desirability increased towards the centre of the sanctuary, marked by the Apollo temple. Only the most majestic portraits were to be seen (and read). Statues representing famous kings, emperors, or warriors drew everyone’s attention. Their neighbouring spots became desirable by virtue of spatial contiguity, the allure of primary dedications radiating towards secondary portraits clustered around them.Footnote 62 In the succinct words of Ma, ‘statues attract statues’: one dedication attracted other ones, which, in turn, attracted further ones, like pieces of metal that, clinging to the magnet, become magnetised themselves.Footnote 63 Proximity to other famous statues, whether of deities, personifications, or mortals, gave a different perspective in which an honorific statue could be interpreted.Footnote 64 Perrin-Saminadayar noticed that the same situation is discernible also in Athens and Olympia.Footnote 65 This phenomenon – space desirability enhancement – comes to the foreground at the Delphic eastern temple terrace, which becomes a venue for honouring only the most outstanding characters. The prestige of the site derived not only from the temple (primary prestige) but also from numerous statues already housed there (secondary prestige). Dedications adjacent to the eastern temple terrace, initially built to take advantage of the temple’s prestige, eventually added their own measure of prestige (both via their inherent worth and the allure of the location). In turn, they improved the desirability of the surrounding space. This chain reaction, however, led to a rampant overcrowding of the eastern temple terrace and a need for space became apparent. ‘The aim of a portrait statue was to be visible, to make the subject stand out as special – someone to be recognised and celebrated – how might patrons and sculptors have reclaimed prominence and visibility for their monuments in this crowded statue landscape? [...] When placement alone was no longer sufficient to guarantee visibility, what other strategies might have been used to call attention to a portrait monument, to make it stand out from the crowd.’Footnote 66 The competition for scant display space not only seems to explain why the Aetolians in the third century b.c. decided to avoid the eastern terrace by erecting their monuments on the western side of the temple but also why the uncrowded Roman agora became a showground for imperial statues from the fourth century a.d. onwards.Footnote 67

The Northern Regions

In comparison to the southern or south-eastern districts of Delphi, the area to the north of the temple held a sparse number of statues and offerings, with most monuments depicting Macedonian leaders. The region housed a massive family base of Archon of Pella, the satrap of Babylonia, dedicated to him by his compatriots.Footnote 68 Nearby lay another Macedonian monument, the Crateros offering, possibly accompanying the famous representation of Crateros saving the life of Alexander the Great during a lion hunt (no. 540). Another family group statue belongs to the Macedonian commander Alexandros and his wife.Footnote 69 The last extant example is the only surviving marble honorific monument at Delphi, dedicated by Daochos II of Pharsalos. Born Thessalian, he was, nonetheless, Philip II’s close ally, dedicating his family monument at Delphi soon after the battle of Chaeronea.Footnote 70 Significantly, Macedonian portraits did not exclusively occupy the less prestigious northern section of the temenos. Herodotus mentions the earliest Macedonian depiction at Delphi (a statue of Alexander I) situated at the coveted east side of the temple terrace. Unfortunately, it was lost when the Phocians melted it down in the fourth century b.c. Footnote 71

The West Terrace and the West Stoa: The Aetolian Zone

The origin and erection date of the western stoa remain uncertain. The area became a prominent showground for displaying Aetolian spoils and dedications following the repulsion of a Gaulish invasion in 279 b.c. In the third century b.c., the western stoa came to symbolise the dominance of Delphic land by the League.Footnote 72 The western portico held Gaulish spoils and Aetolian commemorative triumphal inscriptions, closely mirroring the Athenian adornment of the eastern terrace area and treasury with fifth-century Persian spoils.Footnote 73 Indeed, the Athenian and Aetolian attempts to monopolise the Delphic statuescape have striking parallels. After 279 b.c., the Aetolian League dedicated a statue of personified Aetolia near the western stoa.Footnote 74 Around the personification appeared images of Eurydamos and other Aetolian generals under his command.Footnote 75 The League’s public monuments in the western temple precinct attracted private dedications from Aetolia. Most of them were erected (as familial honorific images) close to the western temple terraceFootnote 76 but, occasionally, they also encroached upon the eastern temple terraceFootnote 77 and into the aire Footnote 78 . The family monuments dedicated by Aristaineta on the east side were set up on two Ionic columns and dominated the entire landscape.Footnote 79

Interestingly, the Aetolian League had its own sanctuary in Thermos, to be used as a display space for their military triumphs in lieu of the Delphic sanctuary.Footnote 80 Studies on the Aetolian honorific habit in Thermos during the period of Aetolian domination over Delphi reveal several remarkable tendencies. The preserved epigraphic material suggests that the League almost exclusively honoured high-ranking officials and foreigners at Thermos. The extant Thermian portraits and inscriptions praise Aetolian hipparchoi Footnote 81 and magistratesFootnote 82 , as well as Ptolemies (a group statue dated to 240-221 b.c.).Footnote 83 No private individuals appear to have set up honorific statues there. The socially exclusive honorific habit of Thermos contrasts starkly with the multiethnic and more egalitarian Delphic statuescape. This should not surprise: a local shrine did not attract the crowds and publicity Delphi did. As a result, the Aetolian League consciously exploited its influence over Delphi to remodel its sacred landscape, so that it improved the public image of the League. The cultural annexation of the public space at the west side of the Delphic temple, in contrast to its more prominent – and multiethnic – eastern counterpart, allowed Aetolians to demarcate their private communal territory within the cosmopolitan Delphic temenos. It also had an important visual impact: the series of statues erected by the Aetolians appeared more conspicuous than an isolated portrait and carved out space for the addition of further statues which could fill the gaps or continue missing lines.Footnote 84 Monuments set up at Delphi, and indeed other sanctuaries, represented the wealth and fame of the communities that funded them, serving as their cultural markers on foreign territories. To mention but a few examples: the Eretrians, Samians, and Epidaurians respectively set up statues in the shrines of Artemis of Amarythos, Hera, and Asclepios, while the Milesians adopted the shrine of Apollo at Didyma.Footnote 85

Another question is why the Aetolians chose to erect honorific monuments to the west of the temple instead of the more representative eastern area. Scott’s explanation highlights the role of the western entrance (often neglected by scholars): ‘the placement of these monuments on the west end of the temple terrace suggests that the west stoa also performed the function of some kind of major (ceremonial?) access point to the sanctuary from the city, rather than being simply a dead-end annex to the sanctuary’.Footnote 86 Scott’s hypothesis notwithstanding, I would like to propose another explanation. In the third century b.c., the Delphic statuescape by and large reached a point of oversaturation. The initial section of the Sacred Way and the lot near the aire housed Athenian monuments, the east side of the temple terrace accommodated offerings and dedications from communities all around the Mediterranean, the northern flank contained the Macedonians’ monuments, while the western side of the temple still remained devoid of any significant structures. The case study of Aristaineta statues proves that any new addition to the (already overcrowded) east side had to stand out through its sheer size, grandeur, and extravagance. A simpler and cheaper solution entailed erecting an ordinary statue in an emptier lot, where it would attract attention – instead of being overlooked in a glamorous but overcrowded space. The Aetolians transformed the western part of the Delphic temenos into their honorific showground, the western stoa becoming a memorial for their liberation of Delphi. According to my interpretation, the Aetolians aimed not only to turn the western temple side into a visitor magnet on a par with or greater than its opulent eastern counterpart but also to establish a tightly controlled honorific display zone which would serve the propaganda effort of the League. Finding itself in a position to carve out and dominate a part of the Delphic statuescape, the Aetolian League created a space within a space, broadcasting a clear message of superiority among the overcrowded and often confusing displays of statues and inscriptions.

Literary sources and Delphic inscriptions reveal two other locations which deserve further attention. According to Pausanias, an unspecified Marmarian temple housed statues of Roman emperors.Footnote 87 Indeed, a portrait of Hadrian, dedicated by a Delphic priest, turned up in Marmaria, in front of the Doric treasury.Footnote 88 It is not known from the content of the decree where the statue of Memmios Neikandros, a Delphic local hero of the first half of the second century a.d., was situated. I propose that it stood in the Delphic prytaneion, where people could ‘pray there to him as to the hero’.Footnote 89 The citizens of Delphi honoured Neikandros with four statues, which were set up in the most famous cities of Achaia: Delphi, Pisa, Argos, and Corinth. As he was worshipped and commemorated in the Delphic prytaneion, it seems likely that his image would have been placed there as well. After all, portraits of local heroes often stood in public buildings. The Athenian prytaneion, for instance, accommodated statues of Miltiades, Demosthenes, and Themistocles, while the one at Ptolemais housed an image of Lysimachos. Similarly, the Megaran prytaneion contained the graves of the eponymous heroes and that at Sikyon bears traces of a hero cult as well.Footnote 90

Conclusion

In this paper, I have demonstrated how the practice of erecting honorific statues at Delphi varied according to the desirability of particular dedication lots and the political influences Delphi experienced over time. The statue density peaked along the main traffic artery of Delphi, as these exposed spots offered the best visibility for dedications. Prime locations included the main entrance to the sanctuary, the run of the Sacred Way, and the terraces surrounding the temple. The changes in the honorific habit discussed in this paper showcase the chronological evolution of the statuescape and of norms governing honorific monument display at Delphi. The Archaic period – described as Delphi’s golden age – saw the largest number of votive dedications and offerings as well as the erection of the first treasuries.Footnote 91 The inauguration of the Pythian Games in 586 b.c. ensured a steady stream of recurring visitors at Delphi: in consequence, the sanctuary became an excellent showground for honorific monuments throughout the following centuries.

The Persian Wars opened a new chapter in Greek history, with the fifth-century rivalries between Athens and Sparta influencing the Delphic statuary practice. The beginning of the Sacred Way and the east temple terrace swelled with dedications and spoils looted from the enemies. This period also saw the erection of the Athenian treasury and stoa, increasing the desirability of their surroundings and the temenos as a whole.Footnote 92 After the Third Sacred War, the Delphians regained control over their sacred land, their newly won independence manifested through the setting up of new monuments.

During the early Hellenistic period, Delphi granted statuary honours to prominent Macedonians, indicative of the impact Macedonia had on fourth-century Delphi.Footnote 93 The accumulation of Macedonian dedications and monuments north to the temple terrace demonstrates that Macedonians laid claim to this less desirable – yet less crowded – northern lot, changing the Delphic statuary landscape. I have argued here that the once popular dedicatory areas, such as the eastern side of the temple terrace and the southern area along the Sacred Way, grew overcrowded in the early Hellenistic era. New overlords of Delphi wanted to flaunt their power in an increasingly distracting statuescape. They turned to underutilised spaces to the north and west of the temple, strictly controlling the use of newly freed statuary space to avoid the same overcrowding that plagued the eastern and southern sections. The League of the Aetolians established its own zone along the western flank of the temple terrace, as this was the only available area left. At the turn of the third century, the Delphic temenos ran out of room. As a result, the Attalid kings had to break the walls and raise their stoa on the eastern flank, increasing the surface area and capacity of the east side.

In the restless first century b.c., Greece became a battlefield for the forces of Mithridates and Sulla, the ongoing unrest mirrored in the reduced number of honorific statues granted at Delphi.Footnote 94 Throughout the entire Roman period, the poleis of a once Panhellenic Greece grew increasingly inward-looking: the previously cosmopolitan Delphic sanctuary dwindled to a local shrine, all regions of the temenos already choked up with thousands of monuments. Some space might have been freed under Nero, who, according to Pausanias’ account, stole 500 prestigious statues from the sanctuary. And indeed, the previously overburdened eastern part of the sanctuary houses portraits of emperors and prominent Roman officials, added long after the saturation point was reached in the Hellenistic era.Footnote 95 The last significant change in Delphic topography came with the erection of the Roman agora under Hadrian, which contained imperial statues dating from the mid-fourth century onwards. Nonetheless, despite changes in the use of space, the eastern temple terrace remained the most desirable ἐπιφανέστατος τόπος, from Archaic times at least until the Antonine period.

Throughout nearly nine centuries of its use, the Delphic sanctuary served as a Panhellenic propaganda display to announce both personal achievements and state victories – a storyboard that told, or rather re-told, the history of Greece, always from the dedicant’s point of view. A collective memory space and much more beyond that, the Delphic temenos constituted an ideal spot to flaunt one’s power. Erectors of the monuments intended to shape what and who would be remembered by future generations. However, changes in the local statuary habit and the constant evolution of the monumental landscape at times skewed the message dedicators meant to convey. The public space of the temenos was divided, rearranged, overbuilt, and razed during numerous attempts to control the Delphic propaganda storyboard. Specific test cases, such as the Athenian and Aetolian domination, show this process at work. Honorific statues allowed domination to achieve visible form, through them the Athenian and Aetolian presence became physical.

All told, the erection of new honorific statues within the public space always entailed the acknowledgement of portraits and monuments already present at the site, both from a logistical and symbolical perspective. It was a strategy of prominence which included visual impact and ability to remain in the viewer’s memory – and thus a strategy of dominance over the territory. What really mattered was the proper location and configuration with other monuments allowing for constructing the available space. Statues had fronts and backs and a preferred orientation. All this introduced movement into the static landscape, giving power to the space. Honorific portraits allow us to ‘read’ the space not only through legible inscriptions but also through the carefully arranged placement through which they shaped the local topography.