Abstract

We use data on structural primary balances for Latin America to estimate effects of fiscal consolidations. Identification relies on a doubly robust estimator that controls for the endogeneity of fiscal policy using inverse probability weighting. Results suggest a negative multiplier on impact, with the economy starting to recover from the second year on and expanding after 5 years. Revenue-based adjustments are more contractionary on impact than expenditure-based adjustments. Among demand components, we find consumption to be generally less responsive to consolidations than investment. Results also depend on the initial levels of debt and taxation. In comparison with OECD evidence, Latin American countries display larger, but stop-and-go consolidations, with state-dependent long-run multipliers.

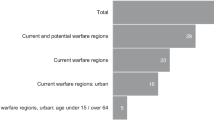

Source: Author’s calculations, using IMF World Economic Outlook data. Dashed lines indicate projected values.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Indeed, most studies on fiscal consolidations rely on OECD data, but even in this case, results are mixed and hinge on both the methodology used for defining fiscal episodes and the identification strategy. Few studies on fiscal multipliers include some emerging economies (also Latin American ones) in the database (e.g., Estevao and Samake 2013; Ilzetzki et al. 2013). The effectiveness of consolidations in improving primary balances or stabilizing debt is analyzed in Mati and Thornton (2008) and Escolano et al. (2014). However, to the best of our knowledge, this paper is the first attempt to study output effects of consolidations for such a comprehensive set of Latin American economies.

See Ardanaz et al. (2015).

Furthermore, impulse responses are estimated by local projections, allowing more flexibility of the functional form.

Espinosa and Senhadji (2011) estimate higher public capital multipliers in comparison with current expenditures for the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC). Estevao and Samake (2013) use a large set of countries, including African and Central American as well as advanced economies. IMF (2015) finds short-lived spending multipliers for Brazil that are lower after the global financial crisis.

Non-Keynesian (expectational) effects rely on frictionless credit markets and forward-looking agents, which facilitate intertemporal consumption and investment allocation.

They document shifts in fiscal variables implemented in year t and announced for a 3-year horizon, following Romer and Romer (2010), and claim that simple changes in structural balances might capture nonpolicy-based measures.

Interestingly, the results of their paper show that a careful analysis using the same data from Guajardo et al. (2014), but recognizing that fiscal adjustments are carried out via plans (not isolated shocks), leads to a picture which is remarkably similar to Alesina and Ardagna’s papers.

Due to lack of consensus on its superiority over other methodologies for identification of episodes, we opt not to pay the high effort cost of constructing such a measure. Moreover, our dataset is less subject to the criticisms that motivate the IMF narrative approach; LAC economies have very procyclical fiscal policies, as documented by the literature (Ilzetzki 2011; Kaminsky et al. 2004) and also according to the results presented in the next sections. Thus, one would not be very worried about positive fiscal shocks reflecting intentions not to let economies overheat. In Appendix, we provide a brief illustration of a narrative measure for three episodes of consolidations.

Structural balances are augmented versions of cyclically adjusted balances (International Monetary Fund 2011). In addition to providing a measure of the fiscal impulse net of cyclical effects (which is done by the CABs), structural balances control for factors such as movements in commodity prices and other nonrecurrent revenues that might affect the analysis of discretionary changes in fiscal policy and provide information on the fiscal stance.

As noted by Medina (2010), fiscal revenues for Latin American economies generally react strongly to commodity price shocks.

Their measure considers an elasticity of expenditures to the cycle equal to zero, claiming that the region has underdeveloped employment insurance systems and a general absence of automatic stabilizers. For robustness checks, we have used estimates of average expenditure elasticities for OECD countries (Girouard and Andre 2005), which are much higher than the values found for OECD’s peripheral economies—the closest approximate for LAC countries, and found no relevant differences in the episodes identified in the next section. For details on the construction of structural balances and the possible fragilities, see Blanchard (1990) and Ardanaz et al. (2015).

This second definition tries to take into account statistics of the observed data rather than arbitrary thresholds to define the episodes.

Details and results for each specific definition can be found in Appendix.

Even a careful narrative approach could be subject to these criticisms, as shown by Jorda and Taylor (2016) for OECD data, and taking into account that there is a degree of subjectiveness present in the transcription of documents into fiscal shocks.

Using only a single approach has some natural flaws: possible uncertainty about the correct parametric or nonparametric specification, or existence of factors that affect the treatment, but not the outcome—or vice versa.

This estimator is more efficient than a regular IPWRA (inverse probability weighting with regression adjustment) estimator and can be understood as a basic inverse probability weighting augmented by an adjustment from the regression estimation weighted by the propensity scores (Jorda and Taylor 2016).

Using univariate standard regressions (OLS), one can directly calculate the coefficients and standard errors using a heteroskedasticity–autocorrelation robust estimator. IRF coefficients are consistent because residuals are a moving average of the forecast errors from time t to \(t+h\) and therefore uncorrelated with regressors, dated \(t-1\) to \(t-p\).

In a nutshell, linear VAR IRFs have limited application, as they provide mirror image responses for positive and negative shocks whose shape is independent of initial conditions and whose magnitudes are only scaled versions of one another. In addition, it is highly improbable that the data generating process is from a short-lag VAR. Studies have provided evidence that many macroeconomic time series are indeed VARMA processes. See, for instance, Cooley and Dwyer (1998).

The AUC provides the area under the ROC (receiver operating characteristics) curve, which computes the rate of true positive and the rate of false positive for each probability level. Probit estimations for each definition are available upon request.

One interesting finding when estimating the propensity score is the significance of elections for fiscal adjustments. Across all specifications and definitions, the occurrence of elections in the previous year was a significant predictor of fiscal episodes. This is in line with the literature, which finds evidence of political budget cycles for emerging economies (for example, Shi and Svensson 2006). We also tried including some other political–institutional variables such as indexes for the quality of institutions, but none of them was significant for any specification.

Only a few episodes in our base happen when country-years have floating exchange rates, according to IMF classification. Hence, it is not possible to divide the sample into two bins to analyze the effects separately. Evidence in Ilzetzki et al. (2013) favors higher multipliers for countries with fixed exchange rates.

We constructed a country-specific commodity index, based on an IMF methodology, to deal with possible commodity price-driven consolidations. It is a well-known fact that commodity prices are an important revenue source for countries like Bolivia, Venezuela, Mexico and Trinidad and Tobago. The fact that these indices are significant predictors of consolidations might indicate imperfections in the SBB measure. Even if this is the case, the propensity score stage works precisely to deal with this problem, given that observations related to high swings in commodity prices receive less weight in the second stage.

In Appendix, we show the distribution of estimated propensity scores in our preferred specification and the amount of overlapping between treated and control groups.

In all regressions, we constrained the coefficients on other explanatory variables to be the same between treated and control groups. In Appendix, we display results without including country fixed-effects and allowing different betas, which does not substantially change the qualitative results.

There is a small caveat in this approach. Direct estimation of local projections does not imply necessarily linear impulse responses, so that simple rescaling might not capture second-order effects, when present. The average treatment dose is thus interesting information that might drive results. Hence, we opted to display both.

One feature of episodes that cannot go unnoticed is the difference between the average size of episodes: The average change in SBBs is 0.97\(\%\) in OECD countries, less than one-fourth of our average episode. In addition, OECD episodes are on average longer than 3 years, while in LAC they rarely last for more than 1 year. This reinforces the volatile character of fiscal policy in our base.

The cumulative effect is calculated as in Jorda and Taylor (2016), by compounding the lost output across the horizon and estimating the impact of the consolidation on this compound change.

Alternative specifications including nominal foreign exchange rate and real interest rates as controls were also conducted, as well as including two lags of past change in consumption/investment; the results remained qualitatively unchanged, although coefficients could change a bit inside the confidence intervals. Tables are available upon request.

References

Alesina, Alberto, and Silvia Ardagna. 1998. Tales of fiscal adjustment. Economic Policy 13(27): 487–545.

Alesina, Alberto, Silvia Ardagna, Roberto Perotti, and Fabio Schiantarelli. 2002. Fiscal policy, profits, and investment. American Economic Review 92(3): 571–589.

Alesina, Alberto and Silvia Ardagna. 2010. Large changes in fiscal policy: taxes versus spending, In Tax policy and the economy, ed. J. Brown, vol. 24, 35–68.

Alesina, Alberto and Silvia Ardagna. 2012. The design of fiscal adjustments. In Tax policy and the economy, ed. J. Brown, vol. 27, 19–67.

Alesina, Alberto, Carlo Favero, and Francesco Giavazzi. 2015. The output effect of fiscal consolidation plans. Journal of International Economics 96: S19–S42.

Alesina, Alberto, Gualtiero Azzalini, Carlo Favero, Francesco Giavazzi, and Armando Miano. 2016. Is it the “how” or the “when” that matters in fiscal adjustments?, NBER working paper no. 22863. Cambridge, Massachusetts: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Alfonso, Antonio. 2006. Expansionary fiscal consolidations in Europe: new evidence, European Central Bank working paper no. 675, September 2006.

Angrist, Joshua D., Oscar Jorda, and Guido Kuersteiner. 2013. Semiparametric estimates of monetary policy effects: string theory revisited, NBER working paper no. 19355. Cambridge, Massachusetts: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Ardanaz, Martin, Ana Corbacho, Alberto Gonzales, and Nuria Caballero. 2015. Structural fiscal balances in Latin America and the Caribbean, IDB working paper series no. 579.

Auerbach, Alan J. and Yuriy Gorodnichenko. 2013. Fiscal multipliers in recession and expansion. In Fiscal policy after the financial crisis, eds. A. Alesina and F. Giavazzi. University of Chicago Press.

Barnichon, Regis, and Christian Matthes. 2015. Understanding the sign of the government spending multiplier: it’s all in the sign. mimeo.

Blanchard, Olivier. 1990. Suggestions for a new set of fiscal indicators, OECD Working Paper No. 79.

Cerulli, Giovanni. 2015. Econometric evaluation of socio-economic programs: theory and applications. Berlin: Springer.

Cooley, Thomas F., and Mark Dwyer. 1998. Business cycle analysis without much theory: a look at structural VARs. Journal of Econometrics 83(1–2): 57–88.

Devries, Pete, Jaime Guajardo, Daniel Leith, and Andrea Pescatori. 2011. A new action-based dataset of fiscal consolidation, IMF working paper no. 11/128. Washington: International Monetary Fund.

Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean. 2010. Economic survey of Latin America and the Caribbean 2009–2010. Santiago: United Nations.

Escolano, Julio, Laura Jaramillo, Carlos Mulas-Granados, and Gilbert Terrier. 2014. How much is a lot? Historical evidence on the size of fiscal adjustments, IMF working paper no. 14/179. Washington: International Monetary Fund.

Espinosa, Raphael, and Abdelhak Senhadji. 2011. How strong are fiscal multipliers in the GCC? An empirical investigation, IMF working paper no. 11/61. Washington: International Monetary Fund.

Estevao, Marcelo, and Issouf Samake. 2013. The economic effects of fiscal consolidation with debt feedback, IMF working paper no. 13/136. Washington: International Monetary Fund.

Giavazzi, Francesco, and Marco Pagano. 1990. Can severe fiscal contractions be expansionary? Tales of two small European countries. NBER Macroeconomics Annual 1990: 95–122.

Girouard, Nathalie and Christophe Andre. 2005. Measuring cyclically-adjusted budget balances for OECD countries, OECD Economics Department working paper no. 434.

Guajardo, Jaime, Daniel Leith, and Andrea Pescatori. 2014. Expansionary austerity: new international evidence. Journal of the European Economic Association 12(4): 949–968.

Ilzetzki, Ethan. 2011. Rent-seeking distortions and fiscal procyclicality. Journal of Development Economics 96: 30–46.

Ilzetzki, Ethan, Enrique Mendoza, and Carlos A. Vegh. 2013. How big (small?) are fiscal multipliers? Journal of Monetary Economics 60: 239–254.

Ilzetzki, Ethan and Carlos A. Vegh. 2008. Procyclical fiscal policy in developing countries: truth or fiction?, NBER working paper no. 14191. Cambridge, Massachusetts: National Bureau of Economic Research.

International Monetary Fund. 2011. When and how to adjust beyond the business cycle? A guide to structural fiscal balances. IMF Fiscal Affairs Department: Technical Notes and Manuals.

International Monetary Fund. 2015. IMF country report no. 15/122. Brazil. Selected issues.

Jorda, Oscar. 2005. Estimation and inference of impulse responses by local projections. American Economic Review 95(1): 161–182.

Jorda, Oscar, and Alan Taylor. 2016. The time for austerity: estimating the average treatment effect of fiscal policy. Economic Journal 126: 219–255.

Kaminsky, Graciela, Carmen Reinhart, and Carlos A. Vegh. 2004. When it rains it pours: procyclical capital flows and macroeconomic policies. In NBER macroeconomics annual 2004, eds. M. Gertler and K. Rogoff, 11–82. National Bureau of Economic Research.

Mati, Amine, and John Thornton. 2008. The exchange rate and fiscal consolidation episodes in emerging market economies. Economic Letters 100: 115–118.

Medina, Leandro. 2010. The dynamic effects of commodity prices on fiscal performance in Latin America, IMF working paper 10/192. Washington: International Monetary Fund.

Menzie, D. Chinn, Hiro Ito. 2006. What matters for financial development? Capital controls, institutions, and interactions. Journal of Development Economics 81 (1): 163–192.

Min, Shi, Jakob Svensson. 2006. Political budget cycles: Do they differ across countries and why?. Journal of Public Economics 90 (8–9): 1367–1389.

Owyang, Michael T., Valerie A. Ramey, and Sarah Zubairy. 2013. Are government spending multipliers greater during periods of slack? Evidence from twentieth-century historical data. American Economic Review Papers and Proceedings 103(3): 129–34.

Perotti, Roberto. 1999. Fiscal policy in good times and bad. Quarterly Journal of Economics 114(4): 1399–1436.

Ramey, Valerie A., and Sarah Zubairy. 2014. Government spending multipliers in good times and in bad: evidence from us historical data, NBER working paper no. 20719. Cambridge, Massachusetts: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Romer, Cristina, and David Romer. 2010. The macroeconomic effects of tax changes: estimates based on a new measure of fiscal shocks. American Economic Review 100: 763–801.

Rosenbaum, Paul R., and Donald B. Rubin. 1983. The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika 70(1): 41–55.

Sutherland, Alan. 1997. Fiscal crises and aggregate demand: can high public debt reverse the effects of fiscal policy? Journal of Public Economics 65: 147–162.

Vegh, Carlos A., and Guillermo Vuletin. 2014. The road to redemption: policy responses to crises in Latin America. IMF Economic Review 62(4): 526–568.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Financial support from FAPESP (Grant 2014/23948-4) is gratefully acknowledged. I am indebted to Bernardo Guimaraes for fruitful discussions and invaluable advice. I would also like to thank Vinicius Barbosa, Thiago Curado, Bruno Ferman, Carolina Garcia, Carlos Eduardo Goncalves, Enlinson Mattos, Marcel Ribeiro, Marcelo Santos, Vladimir Teles, the co-editor Emine Boz, and two anonymous referees, as well as the seminar participants at SBE 2016 (Iguacu), ESEM 2017 (Lisbon) and Sao Paulo School of Economics - FGV for helpful comments.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Appendix

Appendix

1.1 Four Definitions of Fiscal Episodes

The baseline results were presented according to a definition of fiscal adjustment that is, itself, based on the episodes that overlap between four subdefinitions. We here present details on their construction.

Denoting \(\mathrm{AA}_{i,t}\) the occurrence of a fiscal consolidation in country i at period t and \(\mathrm{dSBB}_{i,t}\) the change in the structural primary balance in terms of GDP, our first and second definitions are as follows:

This means that a fiscal adjustment is considered to be happening in a specific year if either: (i) the change in the structural primary balance-to-GDP ratio is greater or equal to X percentage points (a positive change implies a fiscal contraction since revenues minus expenditures increase) or (ii) there is a 2-year consecutive improvement in structural balance of at least Y points per year. We consider two possibilities for X and Y: \((X_1,Y_1) = (2,1.5)\) and \((X_2,Y_2) = (1.5,1.25)\), both expressed as percentage points in terms of GDP. The former resembles Alesina and Ardagna (1998), while the latter is less stringent and was chosen in order to increase the number of observations. We henceforth refer to them as AA1 and AA2.

Alternatively, the third and fourth definitions consider a fiscal episode in terms of the change in SBB relative to the standard deviation of changes along the sample. We consider both changes in structural balances relative to the whole sample standard deviation and the within-country standard deviation. We call those episodes, respectively, SD1 and SD2.

Table 9 presents a summary of fiscal episodes identified by each definition. One important feature of the episodes is a stop-and-go characteristic, given that very few episodes last for more than 2 consecutive years.

Episodes defined as above have a high amount of overlapping between themselves. Comparing the first and second definitions (AA1 and AA2), the latter allows for more episodes since it lowers the threshold and trivially also includes all definitions from the first one. Insofar as the third definition (SD1) considers the whole sample standard deviation, which is higher than country-specific deviation for 13 countries of the sample, a comparison between third and fourth sets of episodes is not so direct. Countries with higher than sample average dSBB standard deviation will tend to lose episodes when country-specific variations are considered, while countries with lower than average dSBB might increase their number of episodes. As seen from the table, the fourth definition has 8 episodes more, but not necessarily all episodes overlap the ones based on the third definition. The third definition is also the only one for which all countries have at least one fiscal episode. Episodes as a proportion of total observations vary between 10 and 16\(\%\).

Table 9 also shows average change in SBB per definition, as well as initial Debt-to-GDP levels and accumulated change in debt up to 3 years prior to consolidation. One can observe that change in SBB is monotonically decreasing with the size of the consolidation treatment group. Also, the more stringent the definition, the higher the initial debt level. On the other hand, accumulated debt prior to adjustment is much higher for the last definition. Table 10 details for each country the identified episodes by definition.

1.2 Quality of SBBs Data: A Small Narrative-Based Assessment

A comprehensive narrative approach along the lines of the IMF approach for OECD countries is an interesting tool to provide a benchmark analysis of fiscal consolidations based on the announced fiscal measures from the budget readings.

In this section, I give an example of such a narrative description of adjustments, analyzing the episodes identified for Trinidad and Tobago, Mexico and Venezuela in 2009. It is a well-known fact that oil-exporting countries suffered greatly as a result of the Great Recession, damaging revenues in terms of both decreases in volume and prices of exports. Hence, it is highly counter-intuitive to find episodes of consolidations for those countries during this period.

Reports (see, e.g., Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean 2010) and data provide interesting figures that help understand the adjustment provided by structural balances. The observation that some consolidations occur during commodity price drops is actually natural based on the definition of the SBBs. If such drops are large enough in comparison with long-run prices, even though primary balances might worsen substantially, structural balances should indeed be improved if the country is taking austerity measures in other revenue or spending items. In what follows, we briefly describe what happened in each of those countries in 2009.

-

Mexico

Public revenues in Mexico declined as the economy slowed. Oil revenues decreased due to lower prices and volumes of exports, and some nonoil tax revenues also fell due to depressed demand. This decline was not totally offset, although there were important rises in nonoil revenues and tax revenues, mainly from transfers of profits from the Central Bank and the oil revenue stabilization fund. In addition, the government cut projected nominal expenditures aiming at maintaining a stable fiscal deficit.

The (unadjusted) primary result was negative, indicating a slight reduction in the deficit in 2009 from 2008. Tax revenues increased already in unadjusted terms. Moreover, after adjustment of taxes for cycle elasticities, tax-based revenues improved further. Hence, it seems plausible after adjusting oil revenues for their respective elasticity (very low prices compared to the “long-run” measure) to observe improvements in structural primary balances, sufficient to classify this period as a consolidation.

-

Venezuela

In Venezuela, the fiscal situation deteriorated due to a drop in government revenues (a decrease in the volume of oil exported and a decline in prices of petroleum). But as in Mexico, some efforts toward increasing tax revenues were conducted, mainly by raising VAT tax rates from 9 to 12.

Current expenditures were increased, like public sector wages and transfers, but capital expenditures were contained. This item receives an elasticity of zero in the IDB method and hence contributes to worsening the fiscal balance, even though some cyclical adjustment could indicate a better figure.

In net terms, the VAT tax increases, boosted by the adjustment for cycle elasticities, plus the long-run adjustment for oil revenues (as in Mexico), generate a significant improvement in the structural budget for 2009, especially when compared to the high deficit from 2008. Therefore, it also sounds plausible to consider the fiscal stance as contractionary.

-

Trinidad and Tobago

Trinidad and Tobago were probably the most affected by decreases in revenues from oil among the three countries. The decrease in international oil and gas prices exceeded forecasts used in the adjusted budget estimates from the government.

In this case, however, the country has not adopted consolidation policies, and hence, the large positive change in (structural) balances was driven by the commodity cycle and the adjustment for price elasticities, which suggests some degree of imperfection in the measure of structural budget balances.

This small narrative example implies two things: (i) First, in 2008, negative structural balances indicate counter-cyclical policies in most economies. In 2009, the budget figure has improved, both because the previous value was very low and because some consolidation effort has been initiated by Mexico and Venezuela, in addition to the long-run adjustment for commodity prices that improves the budget when moving from observed to structural primary balances. (ii) There might be some flaws in the measurement of the fiscal stance by means of the structural balances given that Trinidad and Tobago did not implement significant contractionary measures from 2008 to 2009, but there is a big positive change in the structural balance. This possible weakness is addressed using the two-stage methodology. Likewise, in one of the specifications, we exclude those oil-dependent economies from the sample to double check if this meaningfully changes the effects of baseline estimates.

1.3 Commodity Price Indexes

In the propensity score estimation, we have included two alternative measures of commodity prices, one based on country-specific indices and the other—used as the baseline—based on the main export commodity of the country.

The first measure is a country-specific index based on five major aggregation of commodities: food, beverages, metals, oil and agriculture. The construction of the index is a simplification of the IMF methodology and uses data on specific commodity prices indices. For aggregation of commodity exports into one of these categories, we use UN Comtrade data. For each country i and period t, commodity price indices are constructed according to the following expression:

where P is the price index of each commodity category j, x are exports and m are imports.

The second measure is more simple and aims at increasing the number of observations per country, due to data limitations on the sample of imports and exports. It hence considered the country-specific commodity price index as the price index for the main commodity category in the net exports of each country.

It is apparent from Fig. 8 that this approximation works very well for the main commodity exporters of our sample. The plots display the two measures of commodity indices described. For the case of oil and metal exporters, the country-specific indices closely follow the broader “main commodity” index.

1.4 Distribution of Propensity Scores, Overlapping Assumption

See Fig. 9.

1.5 Robustness Exercises

Table 11 displays results for the four definitions compared to the baseline. One can observe a similar pattern of impulse responses across all of them.

Table 12 displays results allowing different slopes for regressors and not including country FE in the conditional mean equations. In this case, the absence of country fixed-effects shifts the estimates slightly up, implying lower recessions at the beginning and faster output recovery.

1.6 Data Description

See Table 13.

1.7 Allocation Bias

See Fig. 10.