Abstract

This paper investigates the relation between female activity in the labor market and gender wage gaps using regional data from Turkey. Labor force participation of women in Turkey significantly lags behind the developed countries but is increasing. At the same time, raw gender wage gap is quite low in international standards but also increasing. I use the regional variation to analyze the relation between female labor force participation and wage gaps in two steps. First, I estimate the unexplained wage gap, which filters out the gender differences in productivity characteristics for each region and each year between 2009 and 2018, using Household Labor Force Survey data. Then I analyze the relation between gender gap with female labor force participation and other regional characteristics in a panel data regression. The results of the paper suggest that female labor force participation is positively related with both raw and unexplained wage gap. This positive relation partially stems from the fact that women with less unobservable skills or career motivation enter into labor force in the process of increase in female employment rate.

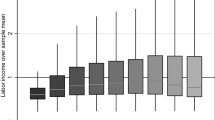

Source: Author’s calculations based on the Household Labor Force Survey

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

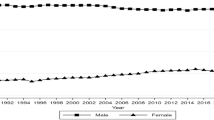

Source: OECD Employment Database, http://www.oecd.org/employment/emp/onlineoecdemploymentdatabase.htm, retrieved 11/21/2019.

11th development plan can be reached at http://www.sbb.gov.tr/kalkinma-planlari/

Bhalotra and Fernandez (2018) provides a simple and intuitive mathematical formulation of the model.

Gender segregation can be separated into two components; vertical and horizontal. Horizontal segregation can be broadly defined as the concentration of men and women in different occupations or industries. Vertical segregation denotes the situation whereby opportunities for career progression for a particular gender within a company or sector are limited. In that respect, Ilkkaracan and Sevim (2007) analyzes the relationship between the gender wage gap and horizontal segregation. However, there is no study that analyzes the relation between vertical segregation and gender wage gap in the Turkish labor market. For a detailed discussion of the definitions, see https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/observatories/eurwork/industrial-relations-dictionary/segregation.

I use the psmatch2 module in Stata for the matching analysis. For technical ils see Leuven and Sianesi (2003).

The reason for choosing 2 years of lag is that the data for school enrollment is available only after 2007.

Illiterate workers are assumed to have 0 years of education and illiterate workers without any diploma are assumed to have 3 years of education. Years of education is approximated as 5 years for primary school graduates, 8 years for secondary school graduates, 11 years for graduates, and 15 years for higher education graduates.

https://biruni.tuik.gov.tr/bolgeselistatistik/, retrieved 5/12/2019.

The instrument is strongly correlated with the female employment rate. The F-test of significance in the first-stage regression is approximately 594.

References

Acemoglu, D., Autor, D. H., & Lyle, D. (2004). Women, war, and wages: The effect of female labor supply on the wage structure at midcentury. Journal of Political Economy, 112(3), 497–551.

Aguayo-Tellez, E., Airola, J., Juhn, C., & Villegas-Sanchez, C. (2014). Did trade liberalization help women? The case of Mexico in the 1990s. In New analyses of worker well-being (pp. 1–35). Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Aldan, A. (2020). Kadın İşgücüne Katılımında Artışın Belirleyicileri: Kuşak Etkisinin Ayrıştırılması (Determinants of the Rise in Female Labor Force Participation: Identifying Cohort Effects). Doğuş Üniversitesi Dergisi, 21(2), 141–156.

Atasoy, B. S. (2017). Female labour force participation in Turkey: The role of traditionalism. The European Journal of Development Research, 29(4), 675–706.

Becker, G. S. (1957). The economics of discrimination. Chicago: University of Chicago press.

Bhalotra, S. R., & Fernandez Sierra, M. (2018). Women’s labor force participation and the distribution of the gender wage gap (No. 11640). IZA Working Paper.

Black, S. E., & Brainerd, E. (2004). Importing equality? The impact of globalization on gender discrimination. ILR Review, 57(4), 540–559.

Blau, F. D., & Kahn, L. M. (2013). Female labor supply: Why is the United States falling behind? American Economic Review, 103(3), 251–256.

Blinder, A. S. (1973). Wage discrimination: Reduced form and structural estimates. Journal of Human Resources, 8(4), 436–455.

Cameron, L. A., Malcolm Dowling, J., & Worswick, C. (2001). Education and labor market participation of women in Asia: Evidence from five countries. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 49(3), 459–477.

Cudeville, E., & Gurbuzer, L. Y. (2010). Gender wage discrimination in the Turkish labor market: Can Turkey be part of Europe? Comparative Economic Studies, 52(3), 429–463.

Dildar, Y. (2015). Patriarchal norms, religion, and female labor supply: Evidence from Turkey. World Development, 76, 40–61.

Gündüz-Hoşgör, A., & Smits, J. (2008). Variation in labor market participation of married women in Turkey. Women’s Studies International Forum, 31(2), 104–117.

Heckman, J. (1979). Sample selection bias as a specification error. Econometrica, 47(1), 153–161.

Hirsch, B., König, M., & Möller, J. (2013). Is there a gap in the gap? Regional differences in the gender pay gap. Scottish Journal of Political Economy, 60(4), 412–439.

Huertas, I. P. M., Ramos, R., & Simon, H. (2017). Regional differences in the gender wage gap in Spain. Social Indicators Research, 134(3), 981–1008.

Ilkkaracan, I., & Selim, R. (2007). The gender wage gap in the Turkish labor market. Labour, 21(3), 563–593.

ILO. (2012). International standard classification of occupations: Structure, group definitions and correspondence tables. Geneva: International Labor Organization.

Johnson, M., & Keane, M. P. (2013). A dynamic equilibrium model of the US wage structure, 1968–1996. Journal of Labor Economics, 31(1), 1–49.

Kara, O. (2006). Occupational gender wage discrimination in Turkey. Journal of Economic Studies, 33(2), 130–143.

Kasnakoğlu, Z., & Dayıoğlu, M. (1997). Female labor force participation and earnings differentials between genders in Turkey. In J. M. Rives & M. Yousefi (Eds.), Economic dimensions of gender inequality: A global perspective. Westport: Praeger.

Katz, L. F., & Murphy, K. M. (1992). Changes in relative wages, 1963–1987: Supply and demand factors. The quarterly journal of economics, 107(1), 35–78.

Kılıç, D., & Öztürk, S. (2014). Türkiye’de Kadınların işgücüne katılımı önündeki engeller ve çözüm yolları: bir ampirik uygulama. Amme İdaresi Dergisi, 47(1), 107–130.

Leuven, E. and Sianesi, B. (2003). PSMATCH2: Stata module to perform full Mahalanobis and propensity score matching, common support graphing, and covariate imbalance testing. Retrieved from 19 September 2020 http://ideas.repec.org/c/boc/bocode/s432001.html.

Mandel, H., & Semyonov, M. (2005). Family policies, wage structures, and gender gaps: Sources of earnings inequality in 20 countries. American sociological review, 70(6), 949–967.

Oaxaca, R. (1973). Male-female wage differentials in urban labor markets. International Economic Review, 14(3), 693–709.

OECD. (2019). Education at a Glance 2019: OECD Indicators. Paris: OECD Publishing.

Olivetti, C., & Petrongolo, B. (2008). Unequal pay or unequal employment? A cross-country analysis of gender gaps. Journal of Labor Economics, 26(4), 621–654.

Özgören, A. A., Ergöçmen, B., & Tansel, A. (2018). Birth and employment transitions of women in Turkey: The emergence of role incompatibility. Demographic Research, 39, 1241–1290.

Rendall, M. (2013). Structural change in developing countries: Has it decreased gender inequality? World Development, 45, 1–16.

Tansel, A. (1994). Wage employment, earnings and returns to schooling for men and women in Turkey. Economics of Education Review, 13(4), 305–320.

Tansel, A. (2005). Public-private employment choice, wage differentials, and gender in Turkey. Economic development and cultural change, 53(2), 453–477.

Tekgüç, H., Eryar, D., & Cindoğlu, D. (2017). Women’s tertiary education masks the gender wage gap in Turkey. Journal of Labor Research, 38(3), 360–386.

Weinberg, B. A. (2000). Computer use and the demand for female workers. ILR Review, 53(2), 290–308.

World Bank. (2014). Turkey’s transitions: Integration, inclusion and institutions. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The views expressed here belong to the author and should not be interpreted as the official views of the Central Bank of the Republic of Turkey.

Appendices

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Aldan, A. Rising Female Labor Force Participation and Gender Wage Gap: Evidence From Turkey. Soc Indic Res 155, 865–884 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-021-02631-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-021-02631-9