Abstract

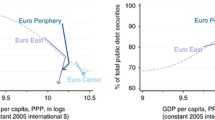

In this paper the authors analyze the potential determinants of US outward FDI stock with a particular focus on the euro effect during the period 1985–2017. To this aim, they consider a large set of candidate variables suggested both by theory and previous empirical analysis. They select the covariates using Bayesian model averaging, a data-driven methodology. Their sample includes a total of 56 host countries, that represent around the 70% of US outward FDI stock. They study the role of the euro on American FDI both in Europe and the rest of the world. In Europe, they consider various country groups: the European Union (EU), the euro area (EA), as well as core and periphery within this last group. They conclude that many variables studied by previous FDI literature cannot be considered robust determinants. Moreover, US OFDI is explained by both horizontal and vertical motives. However, HFDI strategies predominate in EA core countries, whereas VFDI prevails in the periphery. As for the euro effect, the common currency seems to have played an important role encouraging US FDI, being a crucial element in the convergence of EA periphery to its core. In addition, the results indicate that the adoption of the euro has favoured VFDI to the detriment of HFDI.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

As reported in Carril-Caccia and Pavlova (2018) the estimated increase in FDI due to the EU membership ranges between 28 and 83 percentage points, while the incremental effect of euro area membership ranges between 21 and 44 percentage points. However, these studies consider different periods and different sets of countries, so they are not fully comparable. See, i.e. Baldwin et al. (2008), Neary (2009) and Stojkov and Warin (2018).

See also Coeurdacier et al. (2018).

See Helpman (2006).

Ownership, Location and Internalization.

See Dunning (1980).

Obviously, Bayesian statistical techniques have not only been applied to FDI, but also to other fields of economics. These are the cases of export market shares (Benkovskis et al. 2019), the current account balance (Desbordes et al. 2018), the relationship between energy consumption and economic growth (Camarero et al. 2015) and growth models (Fernández et al. 2001). In the present research, we apply a robust probabilistic approach to select the explanatory variables from a large set of potential candidates. For that objective, we use the R-package BayesVarSel (García-Donato and Forte 2015), and apply Bayesian Variable Selection techniques for linear regression models using Gibbs sampling.

If the missing data are unevenly distributed,they may create a selection bias problem that can question the accuracy of the coefficient estimates. This problem is, notwithstanding, relevant in this literature and has been solved using different approaches. For example, Eicher et al. (2012) who introduced Heckit BMA. They use a sample of 46 countries (25 OECD countries) from 1988 to 2000, and FDI flows as the dependent variable. The results show only mixed support for horizontal or export platform FDI theories, whereas the evidence of vertical FDI was quite weak. Jordan and Lenkoski (2018) use a Tobit Bayesian Model Averaging (TBMA) technique to improve the estimation of the inclusion probabilities of Eicher et al. (2012) and develop a full Bayesian model. Such method gives support for roughly the same determinants as the Heckit BMA when modeling the magnitude of FDI flows.

Germany, the Netherlands, France and Belgium not only founded the ERM in 1979 but were also members of the European Snake since 1972.

This dummy captures the different levels of integration, from trade agreements to a common market

This is, by far, the largest group of countries we analyze (a total of 56), and even if we have removed the unobservable time-invariant country heterogeneity from our estimation (see Sect. 3.2), they remain very diverse. A large sample increases the power of the BMA analysis, being able to detect very small size effects, and then, a large number of variables can be considered relevant.

Its posterior mean is positive for the core (HFDI) and negative for the other two groups, that would imply resource seeking FDI or VFDI.

Defined as the sum of US FDI in the host’s neighboring countries wieighted by the distances (see Table 2 for more details).

See Table 2 for the complete list, definition and sources of candidates.

The reason explaining the negative sign of population density is that it could attract a higher concentration of firms looking for abundant and cheaper labour. Consequently, the competition effect could offset the positive spillovers arising from a common pool of resources, deterring the entry of new firms. For more information about competition forces and FDI location, see Crozet et al. (2004).

In the whole sample an important proportion of countries are from Central and Latin America, East Asia, East Europe and Africa. Moreover, the EU group contains the available Central and Eastern European countries.

On the one hand, the positive sign of trade openness of the host country for the whole sample and EA core countries, as well as the negative sign of revenue from trade taxes for the whole sample, would imply that FDI and trade have been complements during the period considered (consistent with VFDI). Similar results were found by Helpman (1984), Helpman and Krugman (1985), Brainard (1997) and Camarero and Tamarit (2004). On the other hand, the mean tariff rate of the host country for the EA group and its periphery, and that one of the revenue from trade taxes for EU countries, would indicate a substitution pattern between trade and FDI and, thus, HFDI (Markusen 1984; Markusen and Venables 1999, 2000; Blonigen 2001).

These variables are corruption, democratic accountability, law and order, bureaucracy quality, protection of property rights, and integrity of the legal system.

References

Alfaro, L., & Charlton, A. (2009). Intra-industry foreign direct investment. American Economic Review, 99(5), 2096–2119.

Alfaro, L., & Chen, M. X. (2015). Multinational activity and information and communication technology (Working Paper, May. Background Note, World Development Report 2016. (pp. 1–28).

Anderson, J. E., & Wincoop, Ev. (2003). Gravity with gravitas : A solution to the border puzzie. The American Economic Review, 93(1), 170–192.

Antonakakis, N., & Tondl, G. (2015). Robust determinants of OECD FDI in developing countries: Insights from Bayesian model averaging. Cogent Economics and Finance, 3(1), 1–25.

Baier, S. L., & Bergstrand, J. H. (2007). Do free trade agreements actually increase members’ international trade? Journal of International Economics, 71(1), 72–95.

Baldwin, R., Di Nino, V., Fontagné, L., De Santis, R., & Taglioni, D. (2008). Study on the impact of the euro on trade and foreign direct investment. European Economy - Economic Papers 2008 - 2015, No 321. Directorate General Economic and Financial Affairs (DG ECFIN), European Commission. https://EconPapers.repec.org/RePEc:euf:ecopap:0321.

Bayarri, M. J., Berger, J. O., Forte, A., & García-Donato, G. (2012). Criteria for Bayesian model choice with application to variable selection. Annals of Statistics, 40(3), 1550–1577.

Bayoumi, T., & Eichengreen, B. (1993). Shocking aspects of European monetary union. Adjustment and Growth in the European Monetary Union, 3949, 193–229.

Benassy-Quere, A., Fontagne, L., & Lahreche-Revil, A. (1999). Exchange rate strategies in the competition for attracting FDI. CEPII Working Paper, 99(16), 3–34.

Benkovskis, K., Bluhm, B., Bobeica, E., Osbat, C., & Zeugner, S. (2019). What drives export market shares? It depends! An empirical analysis using Bayesian model averaging. Empirical Economics, 1–34.

Berger, J. O., & Pericchi, L. R. (2001). Objective bayesian methods for model selection: Introduction and comparison. Lecture Notes - Monograph Series, 38, 135–207.

Berger, J. O., & Sellke, T. (1987). Testing a point null hypothesis: The irreconcilability of P values and evidence. Journal of the American statistical Association, 82(397), 112–122.

Bergstrand, J., & Egger, P. (2007). A knowledge-and-physical-capital model of international trade flows, foreign direct investment, and multinational enterprises. Journal of International Economics, 73(2), 278–308.

Billington, N. (1999). The location of foreign direct investment: An empirical analysis. Applied Economics, 31(1), 65–76.

Blanchard, O., & Acalin, J. (2016). Policy Brief 16-17: What Does Measured FDI Actually Measure? Peterson Institute for International Economics.

Blonigen, B. A. (1997). Frim-specific assets and the link between exchange rates and foreign direct investment. The American Economic Review, 87(3), 447–465.

Blonigen, B. A. (2001). In search of substitution between foreign production and exports. Journal of International Economics, 53(1), 81–104.

Blonigen, B. A., Davies, R. B., & Head, K. (2003). Estimating the knowledge-capital model of the multinational enterprise: Comment. American Economic Review, 93(3), 980–994.

Blonigen, B. A., Davies, R. B., Waddell, G. R., & Naughton, H. T. (2007). FDI in space: Spatial autoregressive relationships in foreign direct investment. European Economic Review, 51(5), 1303–1325.

Blonigen, B. A., & Piger, J. M. (2014). Determinants of foreign direct investment. Canadian Journal of Economics, 47(3), 775–812.

Brainard, S. L. (1997). An empirical assessment of the proximity-concentration trade-off between multinational sales and trade. American Economic Review, 87(4), 520–544.

Brouwer, J., Paap, R., & Viaene, J. M. (2008). The trade and FDI effects of EMU enlargement. Journal of International Money and Finance, 27(2), 188–208.

Bruno, R., Campos, N., Estrin, S., & Tian, M. (2016). Technical Appendix to “The Impact of Brexit on Foreign Investment in the UK ”. Gravitating Towards Europe : An Econometric Analysis of the FDI Effects of EU Membership. Retrieved fromhttp://cep.lse.ac.uk/ pubs/download/brexit03_technical_paper.pdf.

Buckley, P. J., Clegg, L. J., Cross, A. R., Liu, X., Voss, H., & Zheng, P. (2007). The determinants of Chinese outward foreign direct investment. Journal of International Business Studies, 38(4), 499–518.

Busse, M., Königer, J., & Nunnenkamp, P. (2010). FDI promotion through bilateral investment treaties: More than a bit? Review of World Economics, 146(1), 147–177.

Camarero, M., Forte, A., Garcia-Donato, G., Mendoza, Y., & Ordoñez, J. (2015). Variable selection in the analysis of energy consumption-growth nexus. Energy Economics, 52, 207–216.

Camarero, M., Gómez-Herrera, E., & Tamarit, C. (2018). New evidence on trade and FDI: How large is the euro effect? Open Economies Review, 29(2), 451–467.

Camarero, M., Montolio, L., & Tamarit, C. (2019). What drives German foreign direct investment? New evidence using Bayesian statistical techniques. Economic Modelling, 83, 326–345.

Camarero, M., & Tamarit, C. (2004). Estimating the export and import demand for manufactured goods: The role of FDI. Review of World Economics, 140(3), 347–375.

Campos, N. F. (2019). The economics of a Brexit. The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics, 1–15.

Campos, N. F., Coricelli, F., & Moretti, L. (2019). Institutional integration and economic growth in Europe. Journal of Monetary Economics, 103, 88–104.

Carr, B. D. L., Markusen, J. R., & Maskus, K. E. (2001). Estimating the knowledge-capital model of the multinational enterprise. The American Economic Review, 93(3), 995–1001.

Carril-Caccia, F., & Pavlova, E. (2018). Foreign direct investment and its drivers: A global and EU perspective. ECB Economic Bulletin, 4, 60–78.

Cebula, R. J. (2011). Economic growth, ten forms of economic freedom, and political stability: An empirical study using panel data, 2003–2007. Journal of Private Enterprise, 26(2), 61–81.

Chakrabarti, A. (2001). The determinants of foreign direct investment: Sensitivity analyses of cross-country regressions. KYKLOS, 54(1), 89–114.

Chaney, T. (2008). Distorted gravity: The intensive and extensive margins of international trade. American Economic Review, 98(4), 1707–1721.

Chiappini, R. (2014). Institutional determinants of Japanese outward FDI in the manufacturing industry. GREDEG Working Papers, 2014(11), 1–27.

Chinn, M. D., & Ito, H. (2006). What matters for financial development? Capital controls, institutions, and interactions. Journal of Development Economics, 81(1), 163–192.

Coeurdacier, N., Barany, Z., & Guibaud, S. (2018). Capital flows in an aging world. CEPR Discussion Paper, 13180, 1–30.

Crozet, M., Mayer, T., & Mucchielli, J. L. (2004). How do firms agglomerate? A study of FDI in France. Regional Science and Urban Economics, 34(1), 27–54.

De Haan, J., Lundström, S., & Sturm, J. E. (2006). Market-oriented institutions and policies and economic growth: A critical survey. Journal of Economic Surveys, 20(2), 157–191.

De Sousa, J., & Lochard, J. (2011). Does the single currency affect foreign direct investment? Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 113(3), 553–578.

Desbordes, R., Koop, G., & Vicard, V. (2018). One size does not fit all... panel data: Bayesian model averaging and data poolability. Economic Modelling, 75(July), 364–376.

Dhingra, S., Ottaviano, G., Sampson, T., & Reenen, J. V. (2016). The impact of Brexit on foreign investment in the UK. London School of Economics and Political Science, 1–12.

Di Giovanni, J. (2005). What drives capital flows? The case of cross-border M&A activity and financial deepening. Journal of International Economics, 65(1), 127–149.

Disdier, A. C., & Head, K. (2008). The puzzling persistence of the distance effect on bilateral trade. Review of Economics and Statistics, 90(1), 37–48.

Disdier, A. C., & Mayer, T. (2004). How different is Eastern Europe? Structure and determinants of location choices by French firms in Eastern and Western Europe. Journal of Comparative Economics, 32(2), 280–296.

Dunning, J. H. (1977). Trade, location of economic activity and the multinational enterprise: A search for an eclectic approach. In The international allocation of economic activity (pp. 395–418).

Dunning, J. H. (1979). Explaining changing patterns of international production: In defense of the electric approach. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 41(4), 269–295.

Dunning, J. H. (1980). Theory toward an eclectic production: Of international tests some empirical. Journal of International Business Studies, 11, 9–31.

Dunning, J. H. (2000). The eclectic paradigm as an envelope for economic and business theories of MNE activity. International Business Review, 9(2), 163–190.

Dür, A., Baccini, L., & Elsig, M. (2014). The design of international trade agreements: Introducing a new dataset. Review of International Organizations, 9(3), 353–375.

Eaton, J., & Tamura, A. (1994). Bilateralism and regionalism in Japanese and U.S. trade and direct foreign investment patterns. Journal of the Japanese and International Economies, 8(4), 478–510.

Egger, P., & Winner, H. (2005). Evidence on corruption as an incentive for foreign direct investment. European Journal of Political Economy, 21(4), 932–952.

Eicher, T. S., Helfman, L., & Lenkoski, A. (2012). Robust FDI determinants: Bayesian model averaging in the presence of selection bias. Journal of Macroeconomics, 34(3), 637–651.

Ekholm, K., Forslid, R., & Markusen, J. (2007). Export-platform foreign direct investment. Journal of the European Economic Association, 5(4), 776–795.

European Comission (2019). Foreign direct investment in the EU. Commission Staff Working Document, SWD (2019).

Feldkircher, M., & Zeugner, S. (2009). Benchmark priors revisited: on adaptive shrinkage and the supermodel effect in Bayesian model averaging. IMF Working Papers, 09(202), 1–43.

Fernández, C., Ley, E., & Steel, M. F. J. (2001). Model uncertainty in cross-country growth regressions. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 16(5), 563–576.

Fernández-Val, I., & Weidner, M. (2016). Individual and time effects in nonlinear panel models with large N. T. Journal of Econometrics, 192(1), 291–312.

Fernández-Val, I., & Weidner, M. (2018). Fixed effects estimation of large: T panel data models. Annual Review of Economics, 10(1), 109–138.

Flam, H. & Nordstrom, H. (2008). The euro impact on FDI revisited and revised. Mimeo (December 2008).

Forte, A., Garcia-Donato, G., & Steel, M. (2018). Methods and tools for Bayesian variable selection and model averaging in normal linear regression. International Statistical Review, 86(2), 237–258.

Froot, K. A., & Stein, J. C. (1991). Review of economics and statistics. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 106(4), 1191–1217.

García-Donato, G. & Forte, A. (2015). BayesVarSelect v. 1.6.0 R Package.

García-Donato, G., & Martínez-Beneito, M. A. (2013). On sampling strategies in Bayesian variable selection problems with large model spaces. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 108(501), 340–352.

George, E. I., & McCulloch, R. E. (1997). Approaches for Bayesian variable selection. Statistica Sinica, 7(2), 339–373.

Ghazalian, P. L., & Amponsem, F. (2019). The effects of economic freedom on FDI inflows: An empirical analysis. Applied Economics, 51(11), 1111–1132.

Gygli, S., Haelg, F., Potrafke, N., & Sturm, J.-E. (2019). The KOF Globalisation Index -revisited. The Review of International Organizations, 14(3), 543–574.

Head, K., & Mayer, T. (2004). Market potential and the location of Japanese investment in the European Union. Review of Economics and Statistics, 86(4), 959–972.

Head, K. & Mayer, T. (2014). Gravity equations: Workhorse, toolkit, and cookbook. In Gopinath, G., Helpman, E., & Rogoff, K. (eds.), Handbook of International Economics (volume 4, chapter 3, 1st edn, pp. 131–195). Elsevier B.V.

Head, K., & Ries, J. (2008). FDI as an outcome of the market for corporate control: Theory and evidence. Journal of International Economics, 74(1), 2–20.

Helpman, E. (1984). A simple theory of international trade with multinational corporations. Journal of Political Economy, 92(3), 451–471.

Helpman, E. (2006). Trade, FDI, and the organization of firms. Journal of Economic Literature, 44(September), 589–630.

Helpman, E., & Krugman, P. (1985). Market structure and foreign trade: Increase Returns Imperfect Competition: Increasing Returns, Imperfect Competition, and the International Economy. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Hyun, H. J. (2006). Quality of institutions and foreign direct investment in developing countries: Causality tests for cross-country panels. Journal of Business Economics and Management, 7(3), 103–110.

Jordan, A., & Lenkoski, A. (2018). Tobit Bayesian model averaging and the determinants of foreign direct investment. Mimeo, 1–27.

Justesen, M. K. (2008). The effect of economic freedom on growth revisited: New evidence on causality from a panel of countries 1970–1999. European Journal of Political Economy, 24(3), 642–660.

Khayat, S. H. (2017). Oil and the location determinants of foreign direct investment inflows to mena countries. Journal of International Business Research, 16(1), 1–31.

Kim, z K. (2004). The impact of the process of economic integration on the relationships between foreign direct investment (FDI) and trade: Cases of Japan and U.S. in European Union. International Area Studies Review, 7(2), 135–148.

Kinoshita, Y., & Campos, N. F. (2003). Why does FDI go where it goes? New evidence from the transition economies. IMF Working Papers, 03(228), 1–31.

Kleinert, J., & Toubal, F. (2010). Gravity for FDI. Review of International Economics, 18(1), 1–13.

Konstantakopoulou, I., & Tsionas, E. (2011). The business cycle in eurozone economies (1960 to 2009). Applied Financial Economics, 21(20), 1495–1513.

Kox, H. L. M., & Rojas-Romagosa, H. (2019). Gravity estimations with FDI bilateral data: Potential FDI effects of deep preferential trade agreements. KVL Economic Policy Research, 01.

Liang, F., Paulo, R., Molina, G., Clyde, M. A., & Berger, J. O. (2008). Mixtures of g priors for Bayesian variable selection. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 103(481), 410–423.

Lui, F. T. (1985). An equilibrium queuing model of bribery. Journal of Political Economy, 93(4), 760–781.

Machin, S. (2001). The changing nature of labour demand in the new economy and skill-biased technology change. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 63(Special Issue), 753–776.

Markusen, J. R. (1984). Multinationals, multi-plant economies, and the gains from trade. Journal of International Economics, 16(3–4), 205–226.

Markusen, J. R., & Maskus, K. E. (2002). Discriminating among alternative theories of the multinational enterprise. Review of International Economics, 10(4), 694–707.

Markusen, J. R., Venables, A., Konan, D. E., & Zhang, K. H. (1996). A unified treatment of horizontal direct investment, vertical direct investment, and the pattern of trade in goods and services. NBER Working Paper Series, 5696, 1–35.

Markusen, J. R., & Venables, A. J. (1999). Multinational firms and the new trade theory. Journal of International Economics, Elsevier, 462, 183–203.

Markusen, J. R., & Venables, A. J. (2000). The theory of endowment, intra-industry and multi-national trade. Journal of International Economics, 52(2), 209–234.

Martí, J., Alguacil, M., & Orts, V. (2017). Location choice of Spanish multinational firms in developing and transition economies. Journal of Business Economics and Management, 18(2), 319–339.

McIntosh, S. (2002). The changing demand for skills. European Journal of Education, 37(3), 229–242.

Miller, T., & Kim, A. B. (2016). 2016 Index of economic freedom: Promoting economic opportunity and prosperity. Washington, DC: Heritage Foundation.

Moral-Benito, E. (2013). Likelihood-based estimation of dynamic panels with predetermined regressors. Journal of Business and Economic Statistics, 31(4), 451–472.

Narciso, A. (2010). The impact of population ageing on international capital flow. SSRN Electronic Journal, 1–28.

Neary, J. P. (2009). Trade costs and foreign direct investment. International Review of Economics and Finance, 18(2), 207–218.

Neumayer, E., & Spess, L. (2005). Do bilateral investment treaties increase foreign direct investment to developing countries? World Development, 33(10), 1567–1585.

Noorbakhsh, F., Paloni, A., & Youssef, A. (2001). Human capital and FDI inflows to developing countries: New empirical evidence. World Development, 29(9), 1593–1610.

Othman, N., Yusop, Z., Andaman, G., & Ismail, M. M. (2018). Impact of government spending on FDI inflows: The case of Asean-5, China and India. International Journal of Business and Society, 19(2), 401–414.

Petroulas, P. (2007). The effect of the euro on foreign direct investment. European Economic Review, 51(6), 1468–1491.

Raftery, A. E. (1995). Bayesian model selection in social research. Sociological Methodology, 25, 111–163.

Rose-Ackerman, S., & Tobin, J. (2005). Foreign direct investment and the business environment in developing countries: The impact of bilateral investment treaties. Yale Law and Economics Research Paper, 293, 1–74.

Salem Musibah, A. (2017). Political stability and attracting foreign direct investment: A comparative study of Middle East and North African countries. Sci. Int. (Lahore), 29(3), 679–683.

Shah, N., & Iqbal, Y. (2016). Impact of government expenditure on the attraction of FDI in Pakistan. International Journal of Economics and Empirical Research, 4(4), 212–219.

Sondermann, D., & Vansteenkiste, I. (2019). Did the euro change the nature of FDI flows among member states? European Central Bank. Working Paper Series (p. 2275).

Stojkov, A., & Warin, T. (2018). EU membership and FDI: Is there an endogenous credibility effect? Journal of East-West Business, 24(3), 144–169.

Straathof, B., Linders, G., Lejour, A., & Jan, M. (2008). The internal market and the Dutch economy: Implications for trade and economic growth. CPB Netherlands Bureau for Economic Policy Analysis (p. 168).

Treasury, H. (2016). HM Treasury analysis: The long-term economic impact of EU membership and the alternatives. Parliament by the Chancellor of the Exchequer by command of Her Majesty, April:1–201.

Wei, S.-J. (2000). Local corruption and global capital flows. Review of Economics and Statistics, 82(1), 1–11.

Weidner, M., & Zylkin, T. (2019). Bias and consistency in three-way gravity models. Mimeo, 1–56.

Yeaple, S. R. (2003). The role of skill endowments in the structure of U.S. outward foreign direct investment. Review of Economics and Statistics, 85(3), 726–734.

Zhang, W., & Artis, M. J. (2001). Core and periphery in EMU: A cluster analysis. Economic Issues, 6(2), 39–59.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Astrit Sulstarova for providing us with the extended version of FDI stock from the UNCTAD’s Bilateral FDI Statistics database. Furthermore, we are indebted to Anabel Forte for her help using the BayesVarSel package. This paper has benefited from the comments of the participants in the KOF Euro20 workshop and, in particular from S. Maiani, J. de Haan, D. Furceri and J.E. Sturm. The authors acknowledge the public funding from the EU (ERDF, ESF) and the AEI-Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness ECO2017-83255-C3-3-P project, as well as the Valencian regional government (Generalitat Valenciana-PROMETEO 2018/102 project). Cecilio Tamarit and Mariam Camarero also acknowledge the funding from European Commission project 611032-EPP-1-2019-1-ES-EPPJMO-CoE. The European Commission support does not constitute an endorsement of the contents which reflects the views only of the authors, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein. All remaining errors are ours.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

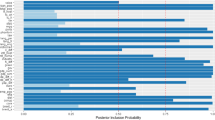

Appendix 1: Trace of posterior inclusion probabilities

The following trace plots are obtained from 20000 iterations, the maximum that the R-function GibbsBvs allows to elaborate such plots. The PIPs are very close to converge with such number of iterations (Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5).

Appendix 2: Posterior inclusion probabilities

About this article

Cite this article

Camarero, M., Moliner, S. & Tamarit, C. Is there a euro effect in the drivers of US FDI? New evidence using Bayesian model averaging techniques. Rev World Econ 157, 881–926 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10290-020-00405-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10290-020-00405-y

Keywords

- FDI determinants

- Foreign direct investment

- US

- European union

- Euro area

- Bayesian model averaging

- Variable selection