Abstract

Stereotypes matter for economic interaction if counterparty utility is informed by factors other than price. Stereotyped agents may engage in efforts to counter stereotype by adapting to in-group standards. We present a model informing the optimal extent of these efforts depending on an agent’s (a) share of total transactions between out- and in-group agents; and (b) share of repeated transaction pairings with in-group counterparties. Low values of (a) suppress the effect of adaptation efforts on the stereotype itself (persistence). In turn, low values of (b) mean that out-group agents cannot dissociate from stereotype (stickiness). Significantly, the model implies that the optimum level of effort may require adaptation beyond in-group standards, and that such over-adaptation attains maximum likelihood in cases where stereotype is sticky and persistent at the same time. We test our model with data on private equity buyout investments conducted in Japan between 1998 and 2015 by domestic Japanese and Anglo-Saxon funds. We document that the latter not only adapt, but eventually over-adapt. In addition, we show that their efforts are effective in reducing a premium initially asked by domestic counterparties.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Stereotypes refer to the association of out-group agents with collective judgments both negative and positive relative to a reference group and are understood as an effort to compensate for incomplete information (Kahnemann and Tversky 1973). Stereotypes matter for human interaction in general, and for economic interaction in particular. Attributes frequently subjected to stereotype include gender (e.g., on performance evaluation in Howlett et al. 2015, and on risk attitudes in Grossman and Lugovskyy 2011) and ethnicity or nationality. The latter associate products and services with particular attributes (Kaynak and Kara 2002; Kotler and Gertner 2002; Chattalas et al. 2008; Herz and Diamantopoulus 2013, Zhang 2015). Generally, stereotypes are used for information processing and can significantly influence expectations and hence the likelihood of a transaction being executed (Chattalas 2015).

Agents crossing cultural boundaries for interaction with other communities face what Akerlof has labeled “a loss of reputation for disobedience of the custom” (Akerlof 1980). Turning his reasoning around, a gain of reputation may represent the motivating force behind assimilation efforts of visitors to a foreign community. The model developed and tested here analyzes the ensuing behavioral dynamics in boundary-crossing agents. Revealed identities enter as the natural prerequisite of stereotyping.

The dynamics between agents from differing communities originate from social customs being intimately linked to preferences (Guiso et al. 2006; Gibson et al. 2013). As the former differ across cultures and as the latter matter for economic behavior, differences in economic outcomes are to be expected. Indeed, culture-specific differences have variously been evidenced in, for instance, an inquiry into the limited participation puzzle (Guiso et al. 2008), public goods experiments (Willinger and Ziegelmeyer 2001), or empirical investigations of entrepreneurial activity (Hayton et al. 2002).

When agents with systematically differing preferences engage in transactions with each other and reveal their identities, stereotypes may cause what is frequently identified as discrimination. Inversely defined as homophily, or home-bias (the tendency of agents to associate with similar others; Kandel 1978; McPherson et al. 2001), their empirical relevance has positively tested, for instance, in public goods experiments with higher contributions by culturally homogeneous groups (Castro 2008, Chen and Li 2009), in finance where cultural proximity is found an important factor in individual (Grinblatt and Keloharju 2001) and institutional equity investments (Kumar et al. 2015), as well as in the wider labor market discrimination literature (e.g., Bertrand and Mullainathan 2004; Roth 2006).

Policy measures (i.e., “collective strategies”) against stereotyping have been variously discussed (e.g., Heinrich 2013, Beaurain and Masclet 2016). In contrast, individual strategies to counter the effect of stereotypical judgment have received less attention so far. Pertaining to this issue, theoretical advances in economics, namely the integration of social context (see for example Arrow 1998; Manski 2000; Brock and Durlauf 2001; Soetevent and Kooreman 2007), have enabled the emergence of a significant literature on the socio-economic integration of immigrants (compare the already comprehensive review in Bisin and Verdier 2001). Within this literature, however, immigrants are assumed to remain in the host country indefinitely (e.g., in labor market analyses such as Chisik 2015, and the experimental study of Cameron et. al 2015). Yet, in “visitors” (e.g., business travelers, foreign subsidiaries, etc.) we see efforts as strategically motivated, with their motivation being conditional on an intent to stay on. Accordingly, only limited cues can be taken from this literature.

To complement existing research on the ‘stereotypist’ (e.g., Bordalo et al. 2016) and on self-stereotyping (Coffman 2014), we develop and test a model of agent response to being stereotyped. Agents who start to compete in a foreign market with revealed identities face a double challenge. The first part of the challenge relates to the differences in their preferences that they might not, or only partially, be aware of. The second part of the challenge originates from them being subject to stereotyping. To paraphrase Akerlof and Kranton (2000:737), visitors typically make what domestic agents regard as “bad decisions”. Being subjected to such judgment, visitors may want to use strategically revealed preferences to signal a change of identity. Accordingly, one can expect rational agents entering a foreign community to emulate the behavior of the dominant group in an attempt at reputation building. As we show, such effort may even imply overcompensation, i.e., adaptation beyond the domestic standard, particularly if stereotypes are sticky and persistent at the same time, and if adaptation efforts are not overly costly. Our model accommodates both negative and positive stereotype, as well as learning effects (pertaining to the existence and weight of stereotype in determining reputation).

For testing the predictions derived from our model, we use field data on a business-to-business services industry, namely private equity buyout investments conducted in Japan between 1998 and 2015 by domestic (in-group) and Anglo-Saxon funds (out-group). We track two behavioral dimensions in Anglo-Saxon visitors with significant level differences relative to domestic standards. Firstly, Anglo-Saxon funds initially display a higher share of turnaround transactions, and—secondly—divest portfolio companies after a c.p. longer period of time (“holding period”). Both aspects can be linked to common negative perceptions of Anglo-Saxon businesses in Japan, namely as overly risk-friendly, and as caring less for the preferences of employees (here, a preference to minimize the period of “organizational uncertainty” linked to fund ownership). Because both aspects imply a reputational risk for their potential domestic counterparties, Anglo-Saxon funds initially offer substantial premiums to compensate for negative stereotype associated with them. However, over time they adapt to local standards, reaching beyond local levels after 2 to 3 years in the market. We further present evidence that their adaptation efforts are effective in bringing down premiums, approaching the level of domestic competitors after about 7 years in the market. While market knowledge of visitor agents accumulates over time and their strategies change accordingly, evidence on shirking in ultimate transactions suggests that agent preferences remain “intact” even if their strategic choices deviate for periods of several years.

This paper is structured as follows. Section 2 sketches our model and derives a set of behavioral predictions. Section 3 introduces our case study and tests a set of hypotheses corresponding to our model’s predictions. Section 4discusses findings and robustness (alternative explanations). Section 5 concludes.

2 Model

2.1 Intuition

We distinguish visitor (foreign; out-group) from domestic (native; in-group) agents competing for transactions with local counterparties. The utility of local counterparties depends on economic value (bid and ask prices, respectively), and on reputation of the prospecting party. Visitors depart on their journey with an expectation of higher profits, which they use to claim a travel budget from investors. In such setting, reputation of visitors is informed by the following two factors: stereotype as pertaining to the country of origin; and individual track record of the prospecting party. In turn, reputation of domestic competitors entirely depends on individual track records (as stereotype toward natives is nil).

Other than using their travel budget for offering more economic value, visitors can increase their odds of winning a transaction through adjustments of their revealed preferences toward local standards, implying adaptation efforts. These efforts are costly because of the net “lower economic returns” that Akerlof and Kranton identify for activities that do not correspond to an agent’s group identity (2000:740), and because a deviation from original preferences affects the identity capital of visitors (Bénabou and Tirole 2016:159). We posit that the opposite holds for positive stereotypes (foreign origin perceived as linked to more virtuous behavior from a domestic perspective). In that case, approximating domestic preferences corresponds to negative efforts implying negative cost, i.e., benefits.

Visitor efforts become effective when prospective domestic counterparties observe their behavior in transactions. This has two implications. Firstly, as efforts only pay off in the subsequent round of bids for a transaction, in their initial transaction visitors will have to use a relatively larger share of their budget for price compensation than in subsequent bids. Accordingly, premiums asked from visitors decrease with their time in the market. Secondly, efforts in an ultimate transaction (i.e., before market exit) are meaningless.

All of the preceding only holds under the assumption of complete information. If, however, agents are unaware of the relevance of reputation, they will continue to act according to their original preferences, which—in turn—means emulating their stereotypical behavior. Empirically, neither pure states of complete, nor incomplete information are pertinent. Rather we suggest with Hayek that markets are learning processes where “individual participants [are] gradually learning the relevant circumstances” (Hayek 1948:100).Footnote 1 In our model, there are plenty of “relevant circumstances” potentially unknown to newly arriving visitors: the very existence and extent of stereotyping, its weight in determining reputation, as well as the possibility of reputation building through effort. Domestic standards and their difference to own original preferences may also not be known; ignorance may even apply to the sign of that difference (messiah complex). As demonstrated by Dekel et al. (2007:697), the observability of preferences is critical for enabling the learning required to reach an evolution toward efficient outcomes. As local standards are revealed in transactions between domestic competitors and fellow visitors, they provide the very “teaching material” for visitors.

In their learning, visitors face a double challenge as they need to make inferences not only about the preferences of domestic counterparties pertaining to reputation, but also about the extent and weight of stereotyping. Whereas visitors may infer the importance attached to the former from observations of all market transactions, the latter can only be inferred from transactions involving peers. Accordingly, the speed of the learning process depends on the number of fellow visitors v as in Ghemawat and Spence (1985), and more exactly on the visitor share in the market. Returns to learning are decreasing as visitors approach complete information.

Importantly, if stereotype is rather sticky and persistent, efforts are not overly costly and the weight of reputation in the utility function of domestic counterparties is substantial, the optimum strategy for visitors may imply to over-adapt to local standards. Technically, this is the case when marginal cost of adaptation remains below that for increasing one’s offering of economic value even after attaining domestic standards.

2.2 Formal model

Visitors engage in an a priori infinite series of one-shot games with revealed identities (as in Healy's model of labor market reputation building, 2007). To account for the monetary nature of prices, we use a quasi-linear utility function of domestic counterparties for economic value EV, and a standard setup for reputation r.

Visitor reputation is informed by the following two factors: stereotype S as pertaining to the country of origin; and the relevant track record of the prospecting party in terms of revealed preferences RP. Reputation of domestic competitors rd is set constant at r* for reasons of simplicity.

Thus, we have:

Substituting EV and r in (1) with (2) yields:

Visitor efforts are strategical deviations from original preferences. For the sake of simplicity, we assume that the average of original visitor preferences OP corresponds to stereotype S associated with them.Footnote 2 Accordingly, displaying revealed preferences RP beyond original preferences requires effort:

As is apparent from (4), in the absence of effort the revealed preferences (market behavior) of visitors are stereotypical. Thus, if visitors are turned down in favor of a domestic competitor, i.e., in spite of EVv > EVd, (4) implies the presence of negative stereotype, i.e., S < r*. Inversely, visitors are subject to positive stereotypes if they happen to win a contract in spite of bids with higher economic value from domestic players, i.e., S > r*.Footnote 3

We note the cost of effort as:

Visitors need to maximize the utility of domestic counterparties given their own budget constraints B. We specify the target function for an n-period case, in which efforts made at time t lead to a better reputation in t + 1, i.e., rv,t = S + et-1. Assuming that no useful efforts can be made prior to market entry, i.e., et=0 = 0, initial reputation rv,t=1equals stereotype S. In turn, with no reputation benefits to reap from effort in the final period, shirking is to be expected, i.e., et=n = 0. As both profits and reputation building critically depend on striking a deal, we further add a sustainability condition demanding equal counterparty utility in all periods, i.e., U1,2, …, n = constant. Substituting RP in (3) with (4), we obtain:

Solving (6) provides optimality conditions for visitors in the n-period case:

Over-adaptation through efforts larger than the differential between domestic reputation r* and stereotype S corresponds to the inequality e > r* − S. Substituting e with its optimality condition (7) and solving for r*, we obtain:

From this, we understand that over-adaptation becomes more likely with increasing k (as the importance attached to reputation). In contrast, the likelihood of over-adaptation becomes smaller with cost c of adaptation efforts and with increasing α as the weight attributed to stereotype in determining reputation (see “Appendix A” for partial derivatives). If S is exaggerating the true mean differences between domestic and visitor preferences (as shown in Bordalo et al. 2016), i.e., if |r* − S| >|r* − OPv|, (5) implies that the cost of effort is actually smaller. As can be inferred from (8), this means that adaptation beyond the mean becomes more likely.

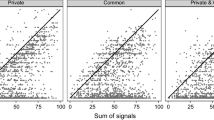

Figure 1 illustrates the main factors moderating the likelihood of over-adaptation (grey area). A large share of repeated transactions between an out-group agent and local counterparties strengthen the effect of individuating information, rendering over-adaptation less likely. Similarly, if the visitor is the only out-group agent in the relevant market (share of out-group transactions = 1), his behavior directly constructs stereotype S. In micro-economic terms, monopoly (only one out-group agent), and monopsony (only one in-group counterparty) represent shares of 1 on both axes. The effect of effort on stereotype is approximately zero for very small shares of total visitor transactions, i.e., δS/δe ≈ 0 (persistent stereotype); and so is the effect of effort on the weight of stereotype in visitor’s reputation as judged by domestic counterparties for very small shares of repeated transactions, i.e., δα/δe ≈ 0 (sticky stereotype). The likelihood of over-adaptation increases with the weight of reputation k, but decreases with increasing effort C and learning speed κτ.

For successful visitor bids, counterparty utility derived from dealing with visitors needs to be larger than utility from transactions with natives:

Substituting EVd in (9) with the budget constraint of (6) and the optimum condition for e in (7) via (2) and (4) and solving for B gives the travel budget required to strike a deal:

While the required level of B increases with the cost of reaching a certain reputation level (less the fraction derived from S), it decreases with the total benefits of reputation. (10) also implies that the budget required for striking a deal decreases with S, i.e., a normatively more positive value of S lessens the required budget.

Under incomplete information, i.e., if agents are unaware of the relevance of reputation, i.e., of k > 0 at time t = 1, they will act according to their original preferences. This effectively reduces (10) to a much simpler budget under incomplete information BII > r*k − Sk, where BII needs to provide for compensating reputational deficiencies entirely by offering a premium on economic value. Thus, for the market to encourage Hayekian learning in our model, BHL needs to satisfy:

The stock of knowledge in visitors grows along their learning journey and can thus be modeled as knowledge vector κ of visitor i pertaining to relevant circumstance j (model variables), with κi,j ∈ [0;1], where 1 represents complete information and all other states are fractions thereof. Vector loadings are informed by the number of transactions τ observed:Footnote 4

With κτ > 0 and κττ > 0, this representation also incorporates the decreasing marginal knowledge returns to learning. As τ accumulates over time, we may expect visitors to experience an iteration process characterized by |eτ=0| <|ê| and eτ → ê as τ → ∞.Footnote 5 When counterparties start to recognize visitor efforts, premiums asked are supposed to decline.

2.3 Extensions

In our base model, the effect of efforts is limited to the subsequent period, which opens up the opportunity of a fresh start at the very same optimum conditions (7). However, it would be more realistic to assume that the reputation of visitors accrues from their history (sum) of effort and of stereotype as suggested in Brock and Durlauf (2001: Sect. 5.1):

As a consequence, the marginal effect of efforts on revealed preferences (track record) declines with each own transaction, i.e., RPe < 0. Depending on a visitor’s budget, this may have two different consequences. First, visitors with Hayekian budgets according to (11) may find their learning speed outpaced by the increase in cost of optimum effort, which will cause them to abandon their journey. Second, visitors with budgets sufficient for continuously compensating negative stereotypes through premium prices, i.e., B > r*k − Sk, may find themselves already in a lock-in situation when spillovers may happen to cause learning. Thus, the marginal cost of reputation building from a given level of reputation monotonously increases over time, i.e., Ct(rv,t∣rv,t-1) > 0.

While the learning process is still ongoing, i.e.,∣κ∣ < 1, the absolute values of visitors’ efforts are systematically biased down and those of bid prices are biased up relative to outcomes in a state of complete information ∣κ∣ = 1 (eventually to be reached with transaction t*). Given finite time horizons, it may become impossible to reach optimum allocation when marginal reputation benefits from effort reach below par with marginal utility from economic value offered, i.e., Ue∣rv,t-1 < UEV = 1. In a very general vein, this means that ignorance is costly, and that it might be too late to usefully start learning. Depending on visitor budgets, the latter may cause either lock-in or exit, which allows distinguishing four possible cases. Figure 2 summarizes these considerations.

A further refinement to the model would imply the introduction of a decay function describing how the weight attached to an instance of revealed preferences (single item in track record) in the formation of reputation decreases with time [as in Carlson and Rowe (1976), or in similar models involving “forgetting”, e.g., Jaber and Bonney (1997)]. Obviously, such “forgetting” property alleviates the increase in marginal cost of reputation building implied by (13) and will cause t* to increase.

Finally, if domestic players perceive the ratio of visitor to domestic agents v/d as a competitive threat, visitor behavior may cause domestic reputation to become endogenous. This is because domestic agents may start to also deviate from their original preferences in a strategic move to fight off what they (rightly) perceive as increasing competition from visitors. This tendency will be particularly strong if domestic players are not aware of the stereotyping that visitors are subjected to. In that case, decisions of domestic players are guided by visitor bids with superior economic value EVv > EVd and visitor efforts in terms of revealed preferences approaching, or even exceeding, their own standards, i.e., e > r*. As visitors, in turn, may perceive this type of strategic move by domestic players as an attempt to foster reputation, i.e., en = RPn − r* > 0, this can effectively elevate the equilibrium level of revealed preferences (in terms of virtuous behavior) as judged from the perspective of domestic counterparties (and vice versa in case of positive stereotypes).

2.4 Predictions

To begin with, let us consider visitors competing with domestic agents for a transaction at t = 0. In the absence of a local track record, reputation equals stereotype.Footnote 6 Under incomplete information, this suggests:

Prediction 1

In the presence of negative (positive) stereotypes, visitors need to offer more (less) economic value to succeed in bids relative to domestic competitors.

While agents entering a foreign market may have some notions of the cultural differences linked to their country of origin, it is through the participation in and observation of transactions with natives that they learn the effect of these differences on their success rates. Differences may take either sign according to whether they result from positive or negative stereotyping. Given uniform alternative returns, differences imply incentives to either compensate for negative stereotype or to bank on positive stereotype.Footnote 7 This suggests:

Prediction 2

Visitors show a tendency to emulate domestic behavior.

If stereotypes are near sticky and persistent, and if adaptation efforts are not overly costly, i.e., as long as (marginal) adaptation benefits are larger than marginal cost, attempts at improving success rates in bids can lead to over-adaptation.Footnote 8 If visitors eventually start their journey with incomplete information, over-adaptation becomes even more likely. This is because early—ill-informed—visitor behavior will produce statistical evidence that reinforces existing stereotypes. When visitors eventually learn about the stereotyping, even larger efforts will be necessary.

Where sizeable numbers of visitors eventually improve their success rates through reputation building, i.e., leading to them winning a substantial share of deals (i.e., τv/τd >> 0), the market outcomes of domestic agents will become negatively affected. Adding to this necessary condition, the sufficient condition for causing what Bénabou and Tirole have labeled “reputation stealing externality” (2010:6) is over-adaptation. This, in turn, creates incentives for natives to reinforce their original reputational positioning. Depending on the sign of stereotype, this implies elevating (negative stereotype), or lowering the level of revealed preferences (positive stereotype):

Prediction 3

Where the ratio of transactions won by visitors relative to domestic agents is perceived as a competitive threat and visitors over-adapt, natives will display a tendency to reinforce their original reputational positioning.

As suggested by the model (Eq. 7), standard argument expects visitors to skip efforts in ultimate transactionsFootnote 9:

Prediction 4

Behavior in ultimate transactions corresponds to original preferences.

Finally, as visitors continue to adjust their efforts toward the optimum in the course of their learning journey, economic value asked from domestic counterparties can be expected to move accordingly. As efforts improve a visitor’s track records only from the subsequent transaction, a time lag is to be expected:

Prediction 5

Premiums asked from negatively (positively) stereotyped visitors decrease (increase) with a time lag.

3 Empirical tests

There are broadly two ways for empirical testing of the model presented: experimental designs and field data. Experimental study is generally praised for its reliability based on the capacity to minimize bias from unobserved variables. Critics, however, question the validity of experiments on the grounds that reality is insufficiently represented in laboratory settings (Collier and Siebert 1991; Harrison et al. 2007). This conceptual critique certainly applies to the challenge of constructing groups with significant “otherness” characteristics as displayed by visitors and domestic agents in our model. Also, experiments are not well suited to study long-term behavior outside the laboratory. In turn, field data, by its very definition, defy any criticism of insufficient representation of reality. Criticism of the use of field data rather refers to its reliability, particularly so for cross-cultural comparisons where unobserved variables may turn findings upside down (Blind and Lottanti von Mandach 2020).

For the specific purpose of testing our model, however, much of this latter issue is canceled out. This is because interaction between foreign and domestic agents happens in a single market and is embedded in a homogeneous institutional environment (which also eliminates a major concern in cross-cultural analysis; see Karolyi 2016). Against that background, we argue that field data represents the better option for testing our model because it scores high on validity and minimizes threats to reliability.

Measuring the interaction effects of cultural differences on economic outcomes from field data poses two challenges. First, stereotype as a culture-contingent item has to be operationalized and measured in order to study its impact. Second, inferences from observed behavior are challenging because of the reflection problem (Manski 1993, 2000). Attempts to face the first challenge date back to the mid-twentieth century (Kuhn and McPartland 1954; Kluchhohn and Strodtbeck 1961; Haire et al. 1966; England 1967; Rokeach 1973), but it was with Hofstede (1980, 2001) that the interest in measuring culture exploded. Although it is only one of 121 instruments identified in a recent review of attempts to measure culture (Taras et al. 2009) and its use is not undisputed (see, e.g., McSweeney 2002; Ailon 2008, 2009; Karolyi 2016), it remains by far the most pertinent approach, particularly so in financial studies where various key variables can aptly be operationalized (see, e.g., Chu et al. 2010; Hillert et al. 2014; Eun et al. 2015). Furthermore, drawing on probabilistic argument, we argue that differences in cultural dimensions asymptotically report the correct sign with growing distances in Hofstede’s indices. Manski’s reflection problem, in turn, only arises if group composition is not known a priori. In our data, however, the revealed identities of agents imply that this criterion is met. What is more, within-group averages do not map one to one to the contextual (group) effects owing to differences in experience (non-simultaneity of market entry) and to the nonlinearity of learning curves. Accordingly, the rank condition for simultaneous equations as given in Durlauf and Tanaka (2008) is met.

3.1 Case background

To test our predictions, we use a dataset covering the population of buyout investments conducted by all private equity funds registered in Japan between 1998, the year known as the onset of the Japanese buyout industry (Wright et al. 2003), and September 2015. The choice of the empirical case comes with six advantages. First, the vast majority of foreign funds active in Japan hail from Anglo-Saxon economies. This allows distinguishing two distinct homogenous groups of foreign and domestic actors. Second, differences in initial values (i.e., original preferences of Japanese and Anglo-Saxon agents) are very likely to be substantial enough to enable adaptation effects to be discerned. Third, revealed identities, together with the personal interactions that come with private equity transactions, creates a setting in which taste-based discrimination may effectively play out (compare the findings on cross-border venture capital investments in Bottazzi et al. 2016). Fourth, because private equity investments are a market with very little chances of repeated counterparty pairings, stereotypes may safely be assumed to remain sticky, because “prior beliefs can remain relatively undisturbed” (Arrow 1998:97). Fifth, because the number of transactions by Anglo-Saxon agents in the private equity market represents a minuscule share of their total economic activity in Japan, we may equally safely assume stereotype to be persistent. Sixth, Japan scores very high on collectivism (Hofstede 2001) and relatively high on ethnocentrism (Hult et al. 1999, Neuliep et al. 2001; Akhter and Hamada 2003), two characteristics associated with an increased likelihood of stereotype being involved in the evaluation of products and services (Gürhan-Canli and Maheswaran 2000, Chattalas et al. 2008).

A buyout transaction is usually a one-off investment by a general partner, the fund manager, which results in outright or majority control of the investee company (portfolio company). The time between investment and exit is known as the holding period (HP). During the holding period, the fund manager seeks to increase the value of the investee company. We discern between three types of fund managers: keiretsu funds, Japanese independent funds, and foreign funds. The reference group of keiretsu funds are affiliated to large institutions from the inner circle of Japanese big business, such as banks, insurance companies, institutional asset managers, or large general trading houses. Independent fund managers are not affiliated to any institution and are typically owned by management. In our data, there are 35 dependent, 28 independent, and 21 foreign fund managers. Out of the 21 foreign fund managers, 18 are headquartered in the USA or the United Kingdom. Our dataset, assembled and cross-evaluated using government reports, fund websites, press searches and data provided by an independent advisor, includes 545 majority buyout investments into businesses with operations in Japan.

Buyout is used as an umbrella term for four transaction types: business succession, divestment, management support (MBO), and turnaround. These four types of buyout may be applied to either a privately held business or a publicly listed business. The latter are referred to as “take-private transactions” (TP), in which a publicly traded is delisted after acquiring its shares.

Investments can be exited either via an Initial Public Offering (IPO), through a trade sale, i.e., selling the portfolio company to another firm, or by selling it to another buyout firm. The acquisition of a business from another buyout fund is called a secondary buyout deal, or simply “secondary”. In our dataset, this also includes tertiary investments.

3.2 Operationalization

In Japan, Anglo-Saxon business ethics are seen as standing in stark contrast to the so-called Japanese model, which values the interests of stakeholders (especially employees) over those of shareholders, co-operation rather than competition, and long-term orientation rather than short-term maximization (Katzner 2008). This is reflected in a survey by Akhter and Hamada (2003) who find substantial agreement (“agree”, or “strongly agree”) among Japanese respondents to the following statements: “US businesses want to establish monopoly power in Japan” (68%), “are ruthless competitors” (58%), “do not act in the interest of Japan” (79%), and “take more from the Japanese than they give to them” (58%). Foreign buyout funds, in particular, have prominently—and negatively—been featured in a popular 2004 novel, later even turned into a TV series (2007), which already by its choice of title hagetaka (‘vultures’) reinforced existing stereotype. Hardly surprising, deal sourcing has frequently been mentioned as the biggest challenge for foreign buyout fund managers (The Economist 2010). For our purposes, the most considerable cultural distance to the reference group of domestic keiretsu funds is instrumental to discerning the cultural dynamics of our model.

Recalling our earlier probabilistic argument that Hofstede’s dimensions of culture correctly report the sign of differences for very large distances of his measures, we select ‘uncertainty avoidance’ (UA) as it comes with the most substantial distance between the Japanese and Anglo-Saxon societies (index values of 92 for Japan vs. 46 for the US). UA refers to the tendency of agents to avoid situations of uncertainty, quite in the Knightian sense as risk under unknown probabilities.

In the buyout investment business, there are chiefly two variables susceptible to the level of uncertainty avoidance. Firstly, turnaround deals as such represent ultimate uncertainty. Accordingly, we expect Anglo-Saxon visitors to display stronger original preferences for turnaround deals than their Japanese competitors in terms of a ‘kernel of truth’. From the perspective of domestic sellers, engaging into business with an overly venturous investor translates into negative utility as it reflects badly on their own reputation. Consequently, visitors have an incentive to reduce such image. Secondly, from the perspective of an investee company and its employees, ownership by a buyout fund represents a transitory state on the road to becoming part of a larger group (as the fund eventually exits the business to a strategic investor), or to becoming fully independent (through an IPO). As high levels of uncertainty typically characterize this transitory period, longer holding periods imply negative utility to domestic sellers via reputational concerns. In contrast, such considerations do not arise in the case of Anglo-Saxon investors for whom pure profit maximization may even suggest extending holding periods beyond the time necessary for restructuring as long as the expected exit prices increase at a higher rate than opportunity cost. Accordingly, we expect to find c.p. longer holding periods in deals won by visitors.

3.3 Hypotheses

As the assessment of foreign investors is reduced to the corresponding stereotype in initial transactions (compare Eq. 4), we may directly rephrase Prediction 1 into:

Hypothesis 1

Visitors need to offer a premium on bid prices.

As visitors learn about the relevance of reputation and the extent of stereotyping, Prediction 2 suggests adaptation efforts:

Hypothesis 2

Share of turnaround deals and length of holding periods by Anglo-Saxon investors decrease with the number of transactions τ observed in the market.

With 95 of 545 transactions (17.4%) in our data set won by visitors, the necessary condition for a domestic reaction is met. If Hypothesis 2 was to hold and eventually found to include substantial over-adaptation, Prediction 3 thus translates into:

Hypothesis 3

Share of turnaround deals and length of holding period of transactions by domestic investors decrease over time.

Prediction 4 of visitors “defecting” in ultimate transactions can be tested using our data, because a sufficient number of native and visitor funds exit the market during the observation period:

Hypothesis 4

In ultimate deals by Anglo-Saxon investors, a turnaround deal is more frequent and length of holding period is markedly longer.

Finally, with the increasing efforts of visitors at reputation-building being recognized by domestic counterparties, we concretize Prediction 5 into:

Hypothesis 5

Premiums asked from visitors decrease following their adaptation efforts.

3.4 Data and descriptive statistics

In order to obtain the subset relevant to our assessment of a homogenous visitor group, we exclude 16 investments by foreign funds with no Anglo-Saxon background from the population of 545 deals. As calculating our test statistic for turnaround deals (TA) depends on the availability of data on the transaction type, sample size reduces by 23 cases to nTA = 506 (or 92.8% of the population).

In turn, our test statistic for the holding period (HP) naturally depends on data covering investments already concluded. The population of deals exited by 30 September 2015 consists of 415 transactions. Excluding 11 cases of investments with unknown entry years and nine investments by non-Anglo-Saxon foreign funds yields a gross sample size of 395 cases. As the complexity of a transaction—and thus the time required for restructuring—increases with size, we use the log of deal value as control variable. Owing to missing data, sample size decreases by 47 cases. The data also still include 14 so-called flip deals of less than one year, in which a buyout fund merely acts as a business broker. As the holding periods of these deals are short by their very nature, i.e., irrespective of the efforts of fund managers, they do not contribute to reputation building. Consequently, effective sample size is nHP = 334 (or 80.5% of the population).

Finally, estimating premiums paid by foreign investors requires a relative price measure. Whereas transaction values are known for most deals in our data and may be used as enumerator in creating such measure, we do not have data on assets or income as the most common candidates for the denominator (book value of assets or EBIT multiples). We resort to another proxy metric, namely price per fulltime employee (PPE). Controlling for industry-year fixed effects, deal type, and fund-level fixed effects accounts for systematic differences in asset-intensity, profitability, and share of non-regular employment. Indications are that the variable chosen might be even more appropriate than asset or income-based measures. This is because findings from another study on buyout investing in Japan (Blind and Lottanti von Mandach 2021) suggest that upscaling is a pertinent value creation strategy (+ 12.3% average employment growth during holding period). Employment figures and transaction values were available for nPPE = 209. “Appendix B” documents descriptive statistics for the three variables.

4 Results

For testing Hypothesis 1 pertaining to premiums asked from Anglo-Saxon funds, we use OLS to estimate a possible differential versus the base category of domestic keiretsu funds. We control for industry-year fixed effects using a 12 item industry classification and investment (entry) years, and additionally control for fund-level fixed effects by dummy-coding all funds with a minimum of 10 transactions in sample TA. We add further controls for Japanese independent funds (not linked to a keiretsu group) and for investments executed prior to a fund’s first exit. The latter accounts for a premium possibly asked from new market entrants (independent from the distinction of visitors from natives). Table 1 presents estimation output.

As can be seen from Table 1, foreign funds are paying significantly higher prices than domestic competitors with an estimated premium of around 55 million JPY per regular employee (about USD 0.5 million at recent exchange rates). Comparing p-values for the model with (1) and without fund-level fixed effects (2), it becomes obvious that including that control is pertinent. While technically not significant, parameter estimates in (2) for the non-keiretsu and EBFE controls come with the expected signs, suggesting that funds not part of a keiretsu network need to compensate for this lack of reputation with a moderate premium (about 90 k USD) and new market entrants (before first exit) need to spend an additional small premium (about 30 k USD).

Our test statistic for the first adaptation dimension is the binary variable marking turnaround deals versus other deal types. Essentially representing the odds of a turnaround transaction, the use of logit regression is indicated. Given the low value of uncertainty avoidance in Anglo-Saxon cultures, we expect estimate of the corresponding dummy to load with a positive sign, indicating an initially higher share of turnaround deals for Anglo-Saxon investors than for the reference group of keiretsu funds. In turn, Japanese independent funds may more easily deviate from the core norm systems of Japanese business values. Accordingly, we expect the corresponding estimate to equally load with a positive sign. As explanatory variable, we use the number of market transactions τ since a fund’s market entry. This maps the gaining of knowledge through observation of transactions. Learning curves have traditionally been conceptualized as unit cost of production declining with accumulated production volume, which suggests an inverse square root function (Spence 1981; Saviotti and Metcalfe 1984).Footnote 10 This way, our estimation also reflects the marginal returns to learning postulated in our model (Eq. 12). To test Hypotheses 2 and 3 (adaptation efforts in visitor, and in domestic funds), we interact the learning effect with the Anglo-Saxon dummy. Finally, we test Hypothesis 4 (shirking in ultimate transactions), by introducing a corresponding dummy.

Independent of any differences in culture, a buyout fund’s capacity to successfully complete a transaction from investment to exit is crucial for proving operational abilities in a newly entered market. Hence, we expect funds to be hesitant to incur the risk of a failed turnaround deal prior to their first exit. We control for this effect by introducing and interacting a corresponding ‘Entry before first exit’ dummy. Reportedly a supply-driven industry, the availability of turnaround investment opportunities fluctuates along the business cycle. We use the annual number of foreclosures to control for this. Finally, a second regression setup adds additional controls for fund-level effects (introducing dummies for all funds with > 10 transactions during the observation period). Table 2 documents regression output.

Estimates for Anglo-Saxon and non-keiretsu funds are significant in both setups without fund-level fixed effects (which also reflect cultural differences). Coefficients confirm our assumptions pertaining to initial values: Anglo-Saxon funds are about three times more likely to invest in a turnaround transaction, and domestic funds not linked to a keiretsu are about 50 to 60% more likely to do so. These differences level out as visitors accumulate experience: interaction effects on learning from observation produce significant estimates for learning parameter β (compare Eq. 12) for all scenarios in both setups providing solid evidence to Hypothesis 2. Interestingly, adding corresponding interactions with the non-keiretsu dummy does not yield any significant estimates for the learning-through-observation parameter.

As the learning of visitors continues, the odds of a turnaround transaction by Anglo-Saxon visitors are reaching par with independent domestic funds after observing about 30 market transactions and with the base category of keiretsu funds after about 80 transactions. Thus, with an average of 30 transactions per year, over-adaptation becomes a reality for visitors after only a few years in the market.

Main effects for market observation were not significant, meaning that Hypothesis 3 cannot be corroborated. Similarly, the dummy for ultimate deals introduced for evidencing defecting agents (Hypothesis 4) did not produce significant estimates in this first behavioral dimension. In contrast, our control for the supply level of turnaround opportunities (annual number of foreclosures) as well as the dummy for Japanese independent funds (non-keiretsu) were significant in all setups and scenarios. Finally, the interaction for the ‘Entry before first exit’-dummy was significantly different from zero in setup 1–1, in contrast to setups 2–1 and 2–2, in which fund fixed effects partially level out this step difference. All models are strongly significant, and neither Hoslem–Lemeshow tests for goodness of fit, nor diagnostics on simulated standardized residuals (Hartig 2017) reveal any major concerns.Footnote 11

As test statistic for the second dimension of cultural difference, we use length of holding period HP. As HP can only be known for investments already exited, the number of transactions observed takes reference to the exit date. While we generally use the same regression setups as before, the time dimension of the test statistic requires additional precautions to account for the finite horizon of our sample. In concrete terms, transactions with early exits or late entries during the observation period are naturally biased toward shorter holding periods. To accommodate for this left and right truncation, we introduce year fixed effects based on exit years for the first part of the sample (until 2005) and for entry years for the later part (from 2006). While a duration model might also be used, we choose OLS for technical considerations.Footnote 12

We add further controls for independent Japanese funds (non-keiretsu, as before) and for the secondary deal type. The latter reflects our assumption that previous buyout investors will already have realized most available “quick wins”, which implies that additional value creation might take more time. Finally, we include a “first-deal” dummy in order to separate the intention to prove full operability (by quickly exiting one’s first deal) from efforts at adaptation. Table 3 documents regression output.

The visitor dummy is significant for all four regressions, and coefficients confirm our assumptions pertaining to initial values: Anglo-Saxon investors initially pay little attention to domestic preferences for minimizing time in conditions of uncertainty (i.e., under fund ownership) before a long-term solution (strategic investor or IPO) can be found. The corresponding estimates indicate that holding periods are almost three years longer than the reference group of keiretsu funds, and about two years longer than independent Japanese funds (non-keiretsu).

As visitors start to learn through market observation, holding periods become shorter: the interaction effect estimating β (compare Eq. 12) is significant in all setups. Parameter estimates suggest that visitors reach par with independent funds after observing about 80 transactions and with keiretsu funds after about 120 transactions. Accordingly, many visitors adapt beyond domestic standards in their third to fourth year in the market.

Main effects for market observation were not significant, meaning that Hypothesis 3 can equally not be corroborated for this second behavioral dimension. In contrast, the dummy for ultimate deals of Anglo-Saxon visitor introduced for evidencing defecting agents (Hypothesis 4) did produce significant estimates significant estimates in both setups (1–2 and 2–2). Notably, the main (domestic) effects also produced significant estimates, albeit with a sign opposite to the interaction. Again, adding corresponding interactions for Japanese independent (non-keiretsu) funds did not produce any significant estimates.

The secondary deal type proves a valid control, with estimates indicating that holding periods last about 6 to 8 months longer for this type. Similarly, controlling for size as approximated in terms of value produces significant estimates with the average holding period increasing between one and two months for every tenfold increase in deal value. Finally, the control for initial efforts aimed at proving full operability (by swiftly exiting the first deal) confirmed our assumption of shorter holding periods for the first investments of Anglo-Saxon funds.

Overall, all models are significant at the 99% level, and individual variance inflation factors are in the range of 6 or lower, and most below 4 (the most conservative of the frequently suggested thresholds). Residual analytics (residuals vs. fitted, residuals vs. leverage, normal q-q, scale location and heteroscedasticity) did not indicate any major concerns.Footnote 13

For finally testing whether the adaptation efforts of visitors pay off in terms of premiums decreasing (Hypothesis 5), we revert to PPE (price per fulltime employee), our initial test statistic. To that end, we add to our earlier setup (as in Table 1) the number of investment transactions observed. Table 4 documents estimation output.

As can be inferred from Table 4, adaptation efforts are indeed followed by reduced premiums asked from Anglo-Saxon visitors. Yet, it takes about 220 transactions (or more than about 7 years) until estimated premiums reach the level of the reference category of domestic keiretsu funds. Notably, this is substantially longer than the estimated par of adaptation efforts (after about 3 years in the market).

5 Discussion

In line with our model predictions, the negatively stereotyped Anglo-Saxon funds are asked most substantial premiums when entering the Japanese market. In their early transactions, estimates for the visitor dummy document significant differences: Anglo-Saxon investors initially display a higher share of turnaround investments, and longer holding periods. From the perspective of their domestic counterparties, both might reflect negatively on their reputation. This is because the former might be interpreted as an inappropriate level of risk appetite, and the latter might be understood as keeping portfolio companies in an unnecessarily prolonged state of uncertainty. Against that background, premiums asked from visitors are meant to compensate for the disutility (e.g., reputational concerns) linked to dealing with them. Over time, however, Anglo-Saxon investors engage in significant adaptation efforts. Eventually, premiums asked from visitors also decrease albeit at a slower rate than the progress of their adaptation efforts.

Rather than merely emulating domestic behavior, Anglo-Saxon visitors to Japan even exceed domestic reference standards after 3 to 5 years in the market. Such over-adaptation suggests that negative stereotypes are substantial, sticky, and persistent. Interestingly, the trends observed in visitors to Japan are not mirrored in global industry trends, where the share of turnaround deals does not seem to decline as the industry matures (Preqin 2011), and where holding periods have become significantly longer in recent years (Preqin 2015). Put into perspective, our findings provide solid evidence on the effects modeled in Sect. 1 of this paper.

Classical references in the discrimination literature suggest that fully adapting to local standards should be sufficient to compensate for statistical discrimination. Accordingly, over-adaptation as found in our data may indicate exaggerating stereotypes. Yet, in light of the extension suggested to our model, namely that reputation may accrue from the transaction history of visitors, over-adaptation may also represent an attempt at balancing earlier non-adapted behavior. From this inter-temporal perspective, the observed over-adaptation may have resulted exclusively from statistical (i.e., non-exaggerating) discrimination, provided that domestic counterparties do not recognize adaptation tendencies in visitors.

Interacting the dummy for independent (non-keiretsu) Japanese funds with the learning variable did not produce significant estimates in any of the regression setups. This suggests a dimension of context-dependency of stereotypes similar to the one identified by Bordalo et al. (2016), namely that the assessment by a given decision maker (domestic counterparty) may depend on the reference group. Applied to our empirical case, statistical evidence on significant mean differences in revealed preferences (higher share of turnaround deals, longer holding periods) gives rise to stereotyping in the case of Anglo-Saxon visitors, but not in the case of independent domestic funds.Footnote 14

Our estimations did not produce evidence on domestic efforts aimed at reinforcing original reputational positioning in spite of the necessary condition of a significant number of deals won by visitors being met (Hypothesis 3). We argue that this is due to the sufficient condition not being met in our data, because the prevalence of “reputation stealing” (Bénabou and Tirole 2010) through over-adaptation is too low. This—in turn—is due to the convexity of the learning function, implying that only a very minor fraction of cases in our samples will effectively be perceived as surpassing domestic standards during the observation period. As a matter of fact, only about one in two (TA), and one in eight (HP) visitor deals in our sample is won after the estimated surpassing of the reputational standards of domestic keiretsu competitors. In addition, if reputation accrues from the transaction history of agents, effective reputation remains below domestic standards even after a considerable number of individual transactions with over-adapted behaviors. Such “long memory” actually seems to guide domestic counterparts who continue to ask for premiums from Anglo-Saxon visitors for several years even after their behavior has reached par with domestic competitors. With average “price discrimination” thus continuing for the entire observation period, domestic competitors do not (yet) receive a signal strong enough to trigger efforts at repositioning.

Finally, if efforts at adaptation are strategic, i.e., if original preferences of agents remain unchanged, our model suggests that revealed preferences in ultimate deals should revert to original preferences (Hypothesis 4). In our data, we did not find evidence of “shirking” in the first behavioral dimension (TA), but solid evidence was found in the second dimension (HP). This is not entirely surprising if one considers that shirking requires a prior decision to exit the market. At the time of investment, however, many agents arguably do not know that the respective deal may ultimately become their last one, with that decision only being taken at some point in time during the holding period. Accordingly, evidence of shirking on the length of holding period is far more likely to be seen than for the odds of a turnaround deal.

Interestingly, we found inverse (negative) signs in parameter estimates for the main (domestic) effect of ultimate deals on HP attaining significance (setup 1–2), and drawing close to significance levels (setup 2–2). One possible clue to this phenomenon may be drawn from the fact that to visitors, ‘ultimate deal’ means ‘market exit’, whereas in many cases it only means ‘strategic change’ to domestic players. Keiretsu funds, in particular, have an obvious incentive not to jeopardize their group’s overall reputation by smoothly and swiftly folding up a business that they are leaving.

5.1 Robustness

There are two potential objections to the validity of our findings. First, visitor funds may be self-selecting according to the fit of their preferences with domestic standards. In concrete terms, if visitor funds with the largest individual differences to domestic standards decide to exit the market, the remaining group of agents will naturally become more similar to domestic players. Eventually, eight of 18 Anglo-Saxon buyout funds (and 31 of 60 domestic funds) withdraw from the market during our observation period. To test whether their exits were caused by a slow or absent adaptation process according to Fig. 2, we introduced and interacted a ‘later market exit’-dummy marking these funds. This procedure, however, did not produce significant parameter estimates (see “Appendix C”), suggesting that market withdrawal was motivated by factors external to the model. Most importantly, this also suggests that the adaptation tendencies observed are not the result of a selection effect caused by non-adapting funds withdrawing from the market. Pertaining to the funds remaining in the market, the limited number of transactions per fund precludes statistical testing for the lock-in effect noted in Fig. 2. Given the considerable adaptation efforts being made by visitors, however, we doubt that a substantial number of funds were subject to this effect.

A second potential objection is the possibility that unobserved variables are causing the trends in the behavioral dimensions (in spite of residual diagnostics not indicating any issues for either of the regressions). As regards the shortening of holding periods, one might argue that this happens simply because funds eventually learn how to create value at investee companies more swiftly. This would indeed imply that holding periods are not becoming shorter as a result of adaptation efforts. Similarly, the share of turnaround deals may be high in early transactions, simply because the sellers of distressed or insolvent businesses may care little (creditors), or not at all (courts) about the reputation of potential acquirers.

A first argument against these latter two objections can be derived from the difference in learning speed observed for visitors versus natives upon their market entry. If incentives for learning were equal, one would expect natives to be learning faster than visitors, given natives’ information advantage in terms of explicit and tacit knowledge. Our data, however, document the opposite: visitor behavior changes positively, while native behavior remains unchanged (HP), or even takes an opposite direction (increasingly engaging in turnaround situations). Taking this line of thought one step further, we argue that such differential will only arise if visitors have a substantial additional incentive. And a very likely incentive is the perceived need to overcome stereotype.

Whereas this first counter-argument relies on (albeit realistic) conjectures, a second counter-argument directly builds on evidence from our analysis. We have argued that buyout funds entering a new market have an incentive to quickly prove their full operability by successfully bringing a first deal to conclusion (exit) regardless of potential culture-specific differences. Our empirical analysis corroborates this assumption as new entrants show a significant tendency to avoid risky turnaround situations in their initial deals and to exit their first deals more swiftly. This means that visitor agents are actually able to swiftly complete a deal, and to successfully acquire healthy businesses as early as on their very first deal. As they eventually reach their objective of proving operability, however, a willingness to use these abilities then only arises anew as they start to learn about the extent of the stereotyping they are facing.

6 Conclusion

This research has conceptualized what we may refer to as a “visitors to Rome” effect: a tendency of foreign entrants to emulate domestic behavior in transactions with revealed identities. Our model shows how stereotypes form an incentive to adaptation efforts, if counterparty reputation is an argument in the utility function of domestic agents. The model further shows that this leads to over-adaptation if efforts are not overly costly, that it becomes more likely if stereotypes are sticky and persistent in atomistic markets, and/or exaggerating the true difference to domestic standards.

Putting model predictions to the test, our empirical analysis documents how visitor agents learn to build their reputation through strategically revealed preferences. Using two behavioral dimensions with substantial differences in initial values, our analysis has documented how Anglo-Saxon buyout funds in Japan have attempted to counter negative stereotype by avoiding deals with high degrees of uncertainty and by reducing time under uncertainty for their investee companies. Interestingly, both tendencies are not reflected in global private equity trends where the share of turnaround deals does not decline and where length of holding period increases as markets mature. In line with game-theoretic reasoning, we also found evidence of agents reverting to their original preferences in ultimate transactions, which implies that visitor behavior is indeed strategic. Using a proxy variable for the premiums paid by visitors, we evidenced the necessity and effectiveness of adaptation efforts to compensate for stereotype. Adding to this, the substantial and sustained adaptation efforts—with some funds even over-adapting—suggest in itself that the evidence obtained through the proxy variable is pertinent. This is because reverse argument suggests that (1) initial premiums need have been considerable enough to trigger a decision to invest in reputation building, and that (2) premiums need to have been decreasing, because otherwise funds would not have continued their efforts at reputation building.

Methodologically, our research documents how cultural dimensions in the preference structure of agents may indeed be used to track the dynamics ensuing from interactions between heterogeneous agents from field data. We believe that to achieve this, two aspects were instrumental. First, our investigation selected two cultures with very large distances in the relevant dimension (Japanese vs. Anglo-Saxon), which maximizes the likelihood of significant differences. Second, we linked the cultural dimension of uncertainty avoidance to variables quantifiable from financial data. We are inclined to believe that meeting these two conditions will be important in enabling future research on the micro-dynamics between agents with different cultural backgrounds, particularly so when based on field data.

With regard to the additional learning potential on the extent of stereotyping as available from the observation of peer transactions as suggested by our model, future inquiries comparing the learning differentials across different markets would ideally follow an experimental approach such as in Bursztyn, Ederer et al. (2014). Similar considerations apply to the evidencing of domestic response to “reputation stealing” (Bénabou and Tirole 2010; and Prediction 3), where laboratory experiments may allow producing sufficient amounts of low-noise data on over-adapting visitor agents.

Notes

Importantly, entering a learning trajectory from a state of relative ignorance is not to be taken for granted: if visitor budgets are sufficient to compensate for their still unknown reputation gap by offering a premium on economic value relative to domestic competitors, visitors may continue to unconsciously follow an inefficient strategy.

Stereotypes may eventually be exaggerating differences in means (compare Bordalo, Coffman et al. 2016). We revert to this issue later as it affects the likelihood of over-adaptation (assimilation beyond domestic standards).

Similar to Becker et al. (1957), our model thus also includes the notion of disutility d = − (r* − S)k as arising from the tastes of domestic agents.

We have earlier argued that learning speed in terms of δκ/δτ depends on the share of transactions involving peers τp/τm. When detailing (12) into κi,j = β1τmϕ + β2τpϕ this becomes apparent. Here, β1 reflects visitor learning about the relevance of reputation k as drawn from observing all market transactions, whereas β2 adds the extent of learning about stereotyping as drawn from the observation of peer transactions. From the function being strictly positive follows δκ/δτ increasing with share of transaction involving peers: τp/τm.

Absolute values of e are noted here in order to account for cases of positive visitor stereotyping (in which visitors gradually learn to bank on their stereotypes, realizing cost savings from relaxing their standards).

Formally, implications build on the optimality conditions of Eq. (7).

Formally, if Ue > Ce, Eq. (8) indicates over-adaptation.

Formally, the second optimality condition in Eq. (7) ên = 0 directly translates into this prediction.

This equals setting ϕ = 0.5 in Eq. 12.

Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests for uniformity of residuals; residuals plots inspected (q–q, residuals versus predicted, residuals versus main and interaction effect of observation) based on simulated standardized residuals using the DHARMa (Hartig 2017) package in R. Weak auto-correlation of residuals found via Durbin–Watson for model 2–2 with p = 0.07.

Duration models are appropriate when the remaining length of time of a state depends on the time already elapsed (such as survival under a chronic condition), or when independent variables change during the state under scrutiny (such as a co-morbidity arising during the state). Both conditions apply to our data as the ultimate goal of PE investors is exit, and as agents accumulate learning. However, the ‘accelerated lifetime’ specification of the hazard function indicated for this case can be directly estimated using least squares. Accordingly, we choose OLS for its superior consistency using start- and end-year dummies to account for left- and right-censoring.

Three cases of potential outliers were re-examined, but no measurement errors were found.

Independent domestic funds not being aware of being stereotyped (hence, no assimilation effort toward the reference group) represent an alternative explanation that we cannot rule out given the limitations of our data.

References

Ailon G (2008) Mirror, mirror on the wall: culture’s consequences in a value test of its own design. Acad Manag Rev 33(4):885–904

Ailon G (2009) A reply to geert hofstede. Acad Manag Rev 34(3):571–573

Akerlof GA (1980) A theory of social custom of which unemployment may be one consequence. Q J Econ 94(4):749–775

Akerlof GA, Kranton RE (2000) Economics and identity. Q J Econ 115(3):715–753

Akhter SH, Hamada T (2003) Japanese attitudes toward American business involvement in Japan: an empirical investigation revisited. J Consum Mark

Arrow KJ (1998) What has economics to say about racial discrimination? J Econ Perspect 12(2):91–100

Beaurain G, Masclet D (2016) Does affirmative action reduce gender discrimination and enhance efficiency? New experimental evidence. Eur Econ Rev 90:350–362

Becker GS (1957) The economics of discrimination: an economic view of racial discrimination. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL

Bénabou R, Tirole J (2010) Individual and corporate social responsibility. Economica 77(305):1–19

Bénabou R, Tirole J (2016) Mindful economics: the production, consumption, and value of beliefs. J Econ Perspect 30(3):141–164

Bertrand M, Mullainathan S (2004) Are emily and greg more employable than Lakisha and Jamal? a field experiment on labor market discrimination. Am Econ Rev 94(4):991–1013

Bisin A, Verdier T (2001) The economics of cultural transmission and the dynamics of preferences. J Econ Theor 97(2):298–319

Blind G, Lottanti von Mandach S (2020) Not a coincidence: sons-in-law as successors in successful Japanese family firms. Crit Finance Rev 10. https://www.nowpublishers.com/article/Details/CFR-0086

Blind G, Lottanti von Mandach S (2021) Private equity buyouts in Japan: effects on employment numbers. J Jpn Int Econ 59:101121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jjie.2020.101121

Bordalo P, Coffman K, Gennaioli N, Shleifer A (2016) Stereotypes. Q J Econ 131(4):1753–1794

Bottazzi L, Da Rin M, Hellmann T (2016) The importance of trust for investment: evidence from venture capital. Rev Financ Stud 29(9):2283–2318

Brock WA, Durlauf SN (2001) Discrete choice with social interactions. Rev Econ Stud 68(2):235–260

Bursztyn L, Ederer F, Ferma B, Yuchtman N (2014) Understanding mechanisms underlying peer effects: evidence from a field experiment on financial decisions. Econometrica 82(4):1273–1301

Cameron L, Erkal N, Gangadharan L, Zhang M (2015) Cultural integration: Experimental evidence of convergence in immigrants’ preferences. J Econ Behav Organ 111:38–58

Carlson JG, Rowe AJ (1976) How much does forgetting cost? Ind Eng 8(9):40–47

Castro MF (2008) Where are you from? Cultural differences in public good experiments. J Socio-Econ 37(6):2319–2329

Chattalas M, Kramer T, Takada H (2008) The impact of national stereotypes on the country of origin effect: a conceptual framework. Int Mark Rev 25(1):54–74

Chattalas M (2015) National stereotype effects on consumer expectations and purchase likelihood: competent versus warm countries of origin. J Bus Retail Manag Res 10(1):1–9

Chen Y, Li SX (2009) Group identity and social preferences. Am Econ Rev 99(1):431–457

Chu PY, Chang CC, Chen CY, Wang TY (2010) Countering negative country-of-origin effects: the role of evaluation mode. Eur J Mark 44(78):1055–1076

Chui ACW, Titman S, Wei KCJ (2010) Individualism and momentum around the world. J Finance 65(1):361–392

Coffman KB (2014) Evidence on self-stereotyping and the contribution of ideas. Q J Econ 129(4):1625–1660

Collier IL, Siebert H (1991) The economic integration of post-wall Germany. Am Econ Rev 81(2):196–201

Dekel E, Ely JC, Yilankaya O (2007) Evolution of preferences. Rev Econ Stud 74(3):685–704

Durlauf SN, Tanaka H (2008) Understanding regression versus variance tests for social interactions. Econ Inq 46(1):25–28

England GW (1967) Personal value system of American managers. Acad Manag J 10:53–68

Eun CS, Wang L, Xiao SC (2015) Culture and R2. J Financ Econ 115(2):283–303

Ghemawat P, Spence MA (1985) Learning curve spillovers and market performance. Q J Econ 100:839–852

Gibson R, Tanner C, Wagner AF (2013) Preferences for truthfulness: Heterogeneity among and within individuals. Am Econ Rev 103(1):532–548

Grinblatt M, Keloharju M (2001) What makes investors trade? J Finance 56(2):589–616

Grossman PJ, Lugovskyy O (2011) An experimental test of the persistence of gender-based stereotypes. Econ Inq 49(2):598–611

Guiso L, Sapienza P, Zingales L (2006) Does culture affect economic outcomes? J Econ Perspect 20(2):23–48

Guiso L, Sapienza P, Zingales L (2008) Trusting the stock market. J Finance 63(6):2557–2600

Gürhan-Canli Z, Maheswaran D (2000) Cultural variations in country of origin effects. J Mark Res 37(3):309–317

Haire M, Ghiselli EE, Porter LW (1966) Managerial thinking: an international study. Wiley, New York, NY

Harrison GW, List JA, Towe C (2007) Naturally occurring preferences and exogenous laboratory experiments: a case study of risk aversion. Econometrica 75(2):433–458

Hartig F (2017) DHARMa: residual diagnostics for hierarchical (multi-level/mixed) regression models. R package version 0.1.5., Available at: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=DHARMa

Hayek FA (1948) Individualism and economic order. Routledge, London

Hayton JC, George G, Zahra SA (2002) National culture and entrepreneurship: A review of behavioral research. Entrep Theory Pract 26(4):33–52

Healy PJ (2007) Group reputations, stereotypes, and cooperation in a repeated labor market. Am Econ Rev 97(5):1751–1773

Heinrich T (2013) Endogenous negative stereotypes: a similarity-based approach. J Econ Behav Organ 92:45–54

Herz MF, Diamantopoulos A (2013) Activation of country stereotypes: automaticity, consonance, and impact. J Acad Mark Sci 41(4):400–417

Hillert A, Jacobs H, Müller S (2014) Media makes momentum. Rev Financ Stud 27:3467–3501

Hofstede G (1980) Culture’s consequences—international differences in work-related values. Sage, Beverly Hills, CA

Hofstede G (2001) Culture’s consequences—comparing values, behaviors, institutions and organizations across nations. Sage, Thousand Oaks

Howlett N et al (2015) Unbuttoned: The interaction between provocativeness of female work attire and occupational status. Sex Roles 72(3–4):105–116

Hult G, Tomas M, Keillor BD, Lafferty BA (1999) A cross-national assessment of social desirability bias and consumer ethnocentrism. J Glob Mark 12(4):29–43

Jaber MY, Bonney M (1997) A comparative study of learning curves with forgetting. Appl Math Model 21(8):523–531

Kahneman D, Tversky A (1973) On the psychology of prediction. Psychol Rev 80(4):237–251

Kandel DB (1978) Homophily, selection, and socialization in adolescent friendships. Am J Sociol 84(2):427–436

Karolyi GA (2016) The gravity of culture for finance. J Corp Finance 41:610–625

Katzner DW (2008) Culture and economic explanation: economics in the US and Japan. Routledge, Milton Park

Kaynak E, Kara A (2002) Consumer perceptions of foreign products. Eur J Mark 36(7/8):928–949

Kluchhohn FR, Strodtbeck FL (1961) Variations in value orientations. Peterson, Row, Evanston, IL

Kotler P, Gertner D (2002) Country as brand, product, and beyond: a place marketing and brand management perspective. J Brand Manag 9(4):249–261

Kuhn MH, McPartland TS (1954) An empirical investigation of self attitudes. Am Sociol Rev 19:68–76

Kumar A, Niessen-Ruenzi A, Spalt OG (2015) What’s in a name? Mutual fund flows when managers have foreign-sounding names. Rev Financ Stud 28(8):2281–2321

Manski CF (1993) Identification of endogenous social effects: the reflection problem. Rev Econ Stud 60(3):531–542

Manski CF (2000) economic analysis of social interactions. J Econ Perspect 14(3):115–136

McPherson M, Smith-Lovin L, Cook JM (2001) Birds of a feather: homophily in social networks. Ann Rev Sociol 27(1):415–444

McSweeney B (2002) hofstede’s model of national cultural differences and their consequences: a triumph of faith-a failure of analysis. Hum Relat 55(1):89–118

Neuliep JW, Chaudoir M, McCroskey JC (2001) A cross-cultural comparison of ethnocentrism among Japanese and United States college students. Commun Res Rep 18(2):137–146

Preqin (2011) Preqin special report: distressed private equity. Available at: https://www.preqin.com/docs/reports/preqin_special_report_distressed_private_equity.pdf

Private equity spotlight. 2015. Available at: https://www.preqin.com/docs/newsletters/pe/Preqin-Private-Equity-Spotlight-May-2015.pdf

Rokeach M (1973) the nature of human values. Free Press, New York

Roth LM (2006) Selling women short: gender and money on Wall Street. Princeton University Press

Saviotti PP, Metcalfe JS (1984) A theoretical approach to the construction of technological output indicators. Res Policy 13(3):141–151

Soetevent AR, Kooreman P (2007) A discrete-choice model with social interactions: with an application to high school teen behavior. J Appl Econ 22(3):599–624

Spence MA (1981) The learning curve and competition. Bell J Econ 12(1):49–70

Taras V, Rowney J, Steel P (2009) Half a century of measuring culture: review of approaches, challenges, and limitations based on the analysis of 121 instruments for quantifying culture. J Int Manag 15(4):357–373

The Economist, private equity in Japan—The waiting Game, (2010), available at http://www.economist.com/node/15721549 [Accessed 11 June 2017]

Willinger M, Ziegelmeyer A (2001) Strength of the social dilemma in a public goods experiment: an exploration of the error hypothesis. Exp Econ 4(2):131–144

Wright M, Kitamura M, Hoskisson RE (2003) Management buyouts and restructuring Japanese corporations. Long Range Plan 36(4):355–373

Zhang K (2015) Breaking free of a stereotype: should a domestic brand pretend to be a foreign one? Mark Sci 34(4):539–554

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Joji Takeuchi (Asset Management One) for sharing data and industry insights and Jouchi Nakajima (Bank of Japan) for contributing unparalleled econometric wisdom. We further gratefully acknowledge most helpful comments and criticism received from Kurt Dopfer (University of St. Gallen), David Chiavacci, Raji Steineck and Alexander Wagner (University of Zurich), Uta Bolt (University College London), Tobias Buchmann (Hohenheim University), Takuji Saito and Masahiro Kotosaka (Keio University), Sachiko Kuroda (Waseda University), Sotaro Shibayama (Tokyo University), Asli Colpan (Kyoto University) as well as from participants of the First Japan Economy Network Conference in Berlin, and of the EAMSA Conference 2019 for most helpful comments and suggestions. Stefania Lottanti von Mandach gratefully acknowledges financial support through a grant of the Helene Bieber-Fonds. Georg Blind thanks the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science for their supporting of this research with a Bridge grant in 2017 (BR160103).

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Zurich.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix A: First-order derivatives to (8)

Defining the right part of (8) as a function g(c,k,α), we obtain the following partial derivatives:

gk > 0 holds as 1 − k − kLog(c/k) > 0 for c, k ∈ [0,1]. In turn, with k − 1 < 0 and all other elements positive, the signs of gα and gc are negative.

Appendix B: Sample descriptive statistics

See Table 5.

Appendix C: Tests for self-selection

See Table 6.

Rights and permissions