Abstract

The existence of incomplete neutralisation in connection with processes like final devoicing is well-known, but little work exists on typologically more uncommon morphological processes such as Celtic initial mutation. This paper reviews the small existing literature on incomplete neutralisation in initial mutation, showing that no convincing evidence has been found so far, and presents a new nasal airflow study on four speakers of Scottish Gaelic that adds to these negative results.

Radical initial /p/ and /m/ in Scottish Gaelic are neutralised to [v] under the lenition mutation. Vowels following radical initial /m/ in Scottish Gaelic may display either categorical phonological nasalisation or gradient phonetic nasalisation. Nasal airflow in items with radical initial /p/ and /m/ is measured in order to determine whether the degree of vowel nasalisation after [v] in lenited forms is sensitive to the identity of the corresponding radical consonant. LME model comparison finds that only categorical phonological nasalisation, and not gradient phonetic nasalisation, may be subject to morphological conditioning. This is at odds with widespread existing findings for processes such as final devoicing, where the gradient phonetic properties of neutralised segments display sensitivity to paradigmatic effects.

The absence of incomplete neutralisation in initial mutation is consistent with recent proposals that restrict the types of morphophonological processes that may bring about incomplete neutralisation to highly transparent, phonetically natural processes involving conflict between word-specific morphological pressures and language-wide phonotactic constraints. These findings can inform us about the structure of the mental lexicon and the derivation of morphologically complex forms.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Since the 1980s, a large number of studies have uncovered subtle, gradient phonetic differences between segments long thought to be subject to phonological neutralisation. Alongside similarly gradient effects of usage factors such as lexical frequency (Bybee 2001; Pierrehumbert 2002), this incomplete neutralisation poses a challenge to strictly modular feedforward architectures of grammar in which the phonetics is sensitive only to the discrete, categorical output of the phonology, and may be taken as evidence for models in which the phonetics has access to morphological and/or lexical information (Steriade 2000; Ernestus and Baayen 2006, 2007; Kleber et al. 2010; Winter and Röttger 2011; Braver 2013, 2019; Roettger et al. 2014). However, the existing literature on incomplete neutralisation is heavily biased towards a small selection of typologically common morphophonological processes—particularly final devoicing—while far less work exists on more unusual phenomena such as the initial mutations that occur in the Celtic languages.

In this paper I explore the question of whether incomplete neutralisation can be observed in connection with the alternations that occur under initial mutation. I show that the small body of existing work on the topic has so far failed to turn up any convincing evidence for incomplete neutralisation, and I present a new study on Scottish Gaelic with negative results. By identifying categorical and gradient patterns of nasal airflow in four speakers from Lewis, I demonstrate that only phonological nasalisation—and not phonetic nasalisation—may display morphological conditioning. These results provide further evidence that initial mutation does not bring about incomplete neutralisation, and are consistent with recent claims by Hall (2017) and Seyfarth et al. (2019) regarding the kinds of morphophonological alternations with which incomplete neutralisation can and cannot occur.

The structure of the paper is as follows. §2 provides background information on incomplete neutralisation, initial mutation and vowel nasalisation in Scottish Gaelic, and §3 reports on an experiment that explores whether initial mutation in Scottish Gaelic brings about incomplete neutralisation. §4 provides some general discussion and §5 concludes the paper.

2 Background

In this section I provide background information on the topics with which this paper is concerned. §2.1 discusses incomplete neutralisation and phonetic paradigm uniformity effects and shows how they are problematic for a modular architecture of grammar. §2.2 introduces the reader to the initial mutations of the Celtic languages and provides a detailed review of the existing literature on incomplete neutralisation in initial mutation. §2.3 discusses phonological and phonetic patterns of vowel nasalisation in Scottish Gaelic, and the manner in which vowel nasalisation interacts with a neutralising process triggered by an initial mutation.

2.1 Incomplete neutralisation and phonetic paradigm uniformity effects

Morphological paradigms often involve neutralisation, where a phonological contrast that is observable in one part of the paradigm is not realised in another. For instance, in German, the contrast between voiced and voiceless obstruents is neutralised word-finally as a result of final devoicing:

-

(1)

Rad

/ʀaːd/

[ʀaːt]

‘wheel’

cf.

gen

Rades

/ʀaːd-əs/

[ʀaːdəs]

Rat

/ʀaːt/

[ʀaːt]

‘advice’

gen

Rates

/ʀaːt-əs/

[ʀaːtəs]

However, many studies have found that the neutralisation brought about by final devoicing is incomplete. Acoustically, this incomplete neutralisation typically manifests itself in the partial retention by devoiced consonants of certain properties normally associated with voiced consonants, such as shorter closure duration or longer preceding vowel duration. As well as for German (Mitleb 1981; Fourakis and Iverson 1984; Charles-Luce 1985; Port and O’Dell 1985; Port and Crawford 1989; Piroth and Janker 2004), acoustic evidence of incomplete neutralisation in final devoicing has been reported for Catalan (Dinnsen and Charles-Luce 1984; Charles-Luce and Dinnsen 1987), Polish (Slowiaczek and Dinnsen 1985; Tieszen 1997), Russian (Barry 1988; Dmitrieva et al. 2010; Kulikov 2012; Kharlamov 2012, 2014; Shrager 2012), Afrikaans (van Rooy et al. 2003; Kaplan 2017) and Dutch (Warner et al. 2004). It has also been found that listeners perform at above-chance level when attempting to discriminate between minimal pairs that differ only in underlying voicing in German (Port et al. 1984; Port and O’Dell 1985; Port and Crawford 1989), Polish (Slowiaczek and Szymanska 1989), Afrikaans (van Rooy et al. 2003) and Russian (Matsui 2011; Kharlamov 2012, 2015). Besides final devoicing, incomplete neutralisation has also been reported in connection with various other phenomena, such as American English t/d-flapping (Fisher and Hirsh 1976; Fox and Terbeek 1977; Zue and Laferriere 1979; Patterson and Connine 2001; Herd et al. 2010; Braver 2011, 2013, 2014) and Russian unstressed vowel reduction (Padgett and Tabain 2005; Kaplan 2017).

Although statistically significant across large numbers of tokens, the differences between incompletely neutralised segments are small, gradient and not readily perceptible, and may generally be detected only through experimentation and statistical analysis. Under a traditional view of phonology as operating upon discrete symbolic representations, they therefore cannot be comfortably assigned to distinct phonological categories, which is problematic for a strictly modular feedforward architecture of grammar in which the phonetics is sensitive only to the categorical output of the phonology. Nevertheless, it has been suggested that incompletely neutralised segments do in fact have distinct phonological surface representations, rendering the phenomenon compatible with such a framework. Van Oostendorp (2008) argues that a devoiced segment continues to bear an unpronounced [voice] feature which may subtly influence its phonetic interpretation, while Iosad (2017:22–24) considers incomplete neutralisation to occur when fully distinct phonological representations are assigned ranges of phonetic realisations that happen to almost entirely overlap. However, if the phonetics is sufficiently powerful to bring about such near-complete neutralisation of a categorical phonological contrast, then this raises the question of whether a separate categorical phonology is necessary at all.

Because incompletely neutralised forms display subtle traces of the properties of paradigmatically related forms, incomplete neutralisation may be regarded as a type of paradigm uniformity effect. Paradigm uniformity effects at the level of categorical phonology are well-known. For instance, English post-nasal coda g-deletion overapplies in singer /sɪNg-ə/ [sɪŋə] (cf. finger /fɪNgə/ [fɪŋgə]) as a result of its paradigmatic relationship with sing /sɪNg/ [sɪŋ], in which deletion applies transparently. Under a modular architecture this can be handled either by means of cyclicity (Bermúdez-Otero 2011), whereby the deletion rule applies to the stem before suffixation takes place, or by output-output (OO-)correspondence (Kenstowicz 1996; Benua 1997), in which highly-ranked OO-correspondence constraints enforce phonological identity between corresponding morphemes in paradigmatically related forms. Regardless of which approach is correct, paradigm uniformity effects at the level of categorical phonology are unproblematic for a modular architecture. Note that the term incomplete neutralisation is therefore not appropriate for cases where the observed difference is sufficiently large, categorical and readily perceptible to constitute an ordinary phonological contrast—for example, in Friulian final devoicing, vowels before underlyingly voiced stops may be over twice as long as those before underlyingly voiceless ones (Baroni and Vanelli 2000). In this case, neutralisation clearly does not occur in the first place and the surface contrast can be considered straightforwardly phonological.

Unlike those at the level of categorical phonology, paradigm uniformity effects at the level of gradient phonetics can be used to argue for non-modular frameworks in which the phonetics has direct access to morphological and/or lexical information. Steriade (2000) and Braver (2013, 2019) argue that OO-correspondence constraints may make reference to phonetic properties, thus motivating identity between paradigmatically related forms at the level of fine-grained phonetic detail. Regarding incomplete neutralisation in final devoicing, Ernestus and Baayen (2006, 2007), Kleber et al. (2010), Winter and Röttger (2011) and Roettger et al. (2014) favour an exemplar-based approach in which both inflected and uninflected forms are stored together in a phonetically rich lexicon and the production of one form may be subtly influenced by partial co-activation of paradigmatically related forms. Both of these approaches are inherently non-modular, as they discard the traditional distinction between categorical phonology and gradient phonetics.

The overwhelming majority of work on incomplete neutralisation has focused on Indo-European languages and the straightforwardly concatenative morphology that is common throughout that family—notable exceptions include Peng (2000) and Yu (2007), who look at the neutralisation of tonal contrasts in Chinese languages, and Gouskova and Hall (2009) and Hall (2013, 2017), who investigate neutralising processes affecting vowels in a variety of Arabic. It is therefore likely that we do not yet have a complete picture of the types of processes that may bring about incomplete neutralisation. In particular, very little work exists on the Celtic languages, which—although they belong to Indo-European—display a typologically unusual type of morphophonological alternation known as initial mutation. While final devoicing is a highly transparent and phonetically natural process that serves to satisfy a phonotactic constraint, the alternations that occur in connection with initial mutation are different in nature, being directly triggered by the morphology itself. It is therefore far from clear that initial mutation should be subject to the same kinds of paradigmatic effects as have been observed in better-studied alternations. This study investigates an initial mutation in Scottish Gaelic in order to determine whether it brings about complete or incomplete neutralisation.

2.2 Initial mutation

All of the living Celtic languages are characterised by systems of morphophonological alternations in initial consonants known as initial mutations. Radical (unmutated) consonants are replaced by their mutated counterparts under a variety of conditions. For example, possessive particles in Irish and Welsh trigger a variety of mutations on a following noun:

-

(2)

a.

Irish

a cat

[ə

]

]‘her cat’

(radical)

a chat

[ə

]

]‘his cat’

(lenition)

a gcat

[ə

]

]‘their cat’

(eclipsis)

b.

Welsh

eu cath

[i kaːθ]

‘their cat’

(radical)

ei gath

[i gaːθ]

‘his cat’

(soft mutation)

fy nghath

[və ̊ŋaːθ]

‘my cat’

(nasal mutation)

ei chath

[i xaːθ]

‘her cat’

(aspirate mutation)

In Irish, radical initial /k/ undergoes frication to [x] under lenition and voicing to [g] under eclipsis. Meanwhile, in Welsh, radical initial /k/ undergoes voicing to [g] under the soft mutation, nasalisation to [̊ŋ] under the nasal mutation and frication to [x] under the aspirate mutation. An extensive literature exists on the analysis of the initial mutations and their exact place in the grammar (e.g. Hamp 1951; Oftedal 1962; Ellis 1965; Rogers 1972; Ó Dochartaigh 1978; Ewen 1982; Lieber 1983; Ball and Müller 1992; Kibre 1997; Pyatt 1997; Stewart 2004; Green 2006; Wolf 2007; Hannahs 2013; Iosad 2014). Importantly, initial mutation differs from the straightforwardly concatenative morphology that is common throughout Indo-European in that it appears to involve the substitution of one segment for another, although authors such as Lieber (1983, 1987), Wolf (2007) and Iosad (2014, 2017) offer accounts in which the relevant alternations are triggered by the affixation of featural autosegments such as [+continuant], [−spread glottis] or [+nasal]. While the examples in (2) contain an overt local trigger, initial mutations can also display purely morphological conditioning: for example, lenition in Irish marks past tense on verbs and feminine agreement on attributive adjectives. Throughout this paper, I will therefore assume that a set of forms such as Irish [ ] ∼ [

] ∼ [ ] ∼ [

] ∼ [ ] or Welsh [kaːθ] ∼ [gaːθ] ∼ [̊ŋaːθ] ∼ [xaːθ] make up a morphological paradigm and are thus comparable to sets like German [ʀaːt] ∼ [ʀaːdəs].

] or Welsh [kaːθ] ∼ [gaːθ] ∼ [̊ŋaːθ] ∼ [xaːθ] make up a morphological paradigm and are thus comparable to sets like German [ʀaːt] ∼ [ʀaːdəs].

Initial mutation very often brings about neutralisation. In some cases, a particular segment may occur both as radical initial and also as the mutated grade of a different radical initial: for example, initial [bɣ

g] in Irish may represent either radical /bɣ

g] in Irish may represent either radical /bɣ

g/ or the eclipsis grade of radical /pɣ

g/ or the eclipsis grade of radical /pɣ

k/. In other cases, a particular segment may occur as the mutated grade of more than one radical initial: for example, initial [v] in Welsh represents the soft mutation grade of both radical /b/ and radical /m/. A small number of recent studies have investigated whether neutralisations such as these are incomplete, with no convincing positive results. Archangeli et al. (2014) report preliminary results, from three speakers, of an ultrasound study of the articulation of lenited consonants in Scottish Gaelic. The authors compare the position of the tongue body during the articulation of various neutralised consonants, such as [h] from lenition of /

k/. In other cases, a particular segment may occur as the mutated grade of more than one radical initial: for example, initial [v] in Welsh represents the soft mutation grade of both radical /b/ and radical /m/. A small number of recent studies have investigated whether neutralisations such as these are incomplete, with no convincing positive results. Archangeli et al. (2014) report preliminary results, from three speakers, of an ultrasound study of the articulation of lenited consonants in Scottish Gaelic. The authors compare the position of the tongue body during the articulation of various neutralised consonants, such as [h] from lenition of / / (e.g. thachd [haxk] ‘choke’, radical tachd [

/ (e.g. thachd [haxk] ‘choke’, radical tachd [ ]) vs. [h] from lenition of /

]) vs. [h] from lenition of / / (e.g. shad [

/ (e.g. shad [ ] ‘toss’, radical sad [

] ‘toss’, radical sad [ ]) vs. non-alternating [h] (e.g. tha [haː] ‘be.prs’). Although they do report some incomplete neutralisation, the items that they compare are poorly matched for following environment. All of the target consonants are either dorsal or glottal, meaning that the position of the tongue body during their articulation will be highly sensitive to anticipatory co-articulation with the following vowel. In a pair such as thachd [haxk] ‘choke’ (radical tachd [

]) vs. non-alternating [h] (e.g. tha [haː] ‘be.prs’). Although they do report some incomplete neutralisation, the items that they compare are poorly matched for following environment. All of the target consonants are either dorsal or glottal, meaning that the position of the tongue body during their articulation will be highly sensitive to anticipatory co-articulation with the following vowel. In a pair such as thachd [haxk] ‘choke’ (radical tachd [ ]) vs. shad [

]) vs. shad [ ] ‘toss’ (radical sad [

] ‘toss’ (radical sad [ ]), for instance, it is likely that the differing place of articulation of the following consonant results in a slight difference in the articulation of the vowel, which in turn will be reflected in the position of the tongue body during [h]. Some pairs involve a short vowel vs. a long vowel, e.g. dhiubh [ju] ‘of them’ (non-alternating) vs. ghiùlain [

]), for instance, it is likely that the differing place of articulation of the following consonant results in a slight difference in the articulation of the vowel, which in turn will be reflected in the position of the tongue body during [h]. Some pairs involve a short vowel vs. a long vowel, e.g. dhiubh [ju] ‘of them’ (non-alternating) vs. ghiùlain [ ] ‘behave’ (radical giùlain [

] ‘behave’ (radical giùlain [ ]), or a short vowel vs. the first element of a diphthong, e.g. ghabh [ɣav] ‘take’ (radical gabh [kav]) vs. dhall [

]), or a short vowel vs. the first element of a diphthong, e.g. ghabh [ɣav] ‘take’ (radical gabh [kav]) vs. dhall [ ] ‘blind’ (radical dall [

] ‘blind’ (radical dall [ ]), where an exact match in quality is not necessarily to be expected. Additionally, one of the three speakers is from Lewis, where it is well documented that [u(ː)] displays a highly distinct retracted allophone next to velarised consonants such as [

]), where an exact match in quality is not necessarily to be expected. Additionally, one of the three speakers is from Lewis, where it is well documented that [u(ː)] displays a highly distinct retracted allophone next to velarised consonants such as [ ] (Borgstrøm 1940:32–33; Oftedal 1956:75; Ladefoged et al. 1998; Nance 2011), and gabh ∼ ghabh is normally pronounced [kɔ ∼ ɣɔ], potentially rendering these pairs very poorly matched for this speaker in particular. I therefore do not consider these results to be convincing evidence for incomplete neutralisation.

] (Borgstrøm 1940:32–33; Oftedal 1956:75; Ladefoged et al. 1998; Nance 2011), and gabh ∼ ghabh is normally pronounced [kɔ ∼ ɣɔ], potentially rendering these pairs very poorly matched for this speaker in particular. I therefore do not consider these results to be convincing evidence for incomplete neutralisation.

As part of a broader psycholinguistic study, Ussishkin et al. (2017) investigate whether speakers of Scottish Gaelic are able to discriminate between [f] from lenition of /p/ (e.g. phioc [f̯ioxk] ‘pick’, radical pioc [ph̯ioxk]) and [f] representing radical /f/ (e.g. feòrag [f̯ioːɾak] ‘squirrel’). No statistically significant effect is found.

Welby et al. (2017; see also

2011, 2014) investigate whether Irish [bɣ g] from eclipsis of /pɣ k/ (e.g. gcasúr [ ] ‘hammer’, radical casúr [

] ‘hammer’, radical casúr [ ]) differ acoustically from [bɣ g] representing radical /bɣ g/ (e.g. gadaí [

]) differ acoustically from [bɣ g] representing radical /bɣ g/ (e.g. gadaí [ ] ‘robber’). No statistically significant effect is found for VOT, consonant duration or closure duration, but the average intensity of the stop burst is found to be significantly greater for [bɣ g] from eclipsis of /pɣ k/ than for [bɣ g] representing radical /bɣ g/. However, as acknowledged by the authors themselves, this study encounters a serious problem. All of the target items are nouns immediately preceded by the definite article an [

] ‘robber’). No statistically significant effect is found for VOT, consonant duration or closure duration, but the average intensity of the stop burst is found to be significantly greater for [bɣ g] from eclipsis of /pɣ k/ than for [bɣ g] representing radical /bɣ g/. However, as acknowledged by the authors themselves, this study encounters a serious problem. All of the target items are nouns immediately preceded by the definite article an [ ], which may be realised with or without [

], which may be realised with or without [ ]. In the eclipsis items, eclipsis is triggered by the presence of a preposition (e.g. ar an gcasúr [εɾj

]. In the eclipsis items, eclipsis is triggered by the presence of a preposition (e.g. ar an gcasúr [εɾj

)

)  ] ‘on the hammer’), while no preposition is present in the radical items (e.g. an gadaí [

] ‘on the hammer’), while no preposition is present in the radical items (e.g. an gadaí [ ] ‘the robber’). Unexpectedly, it is found that the [

] ‘the robber’). Unexpectedly, it is found that the [ ]-less variant of the article occurs far more frequently after prepositions than when no preposition is present. Because the authors were unable to control for this, any difference in average burst intensity between eclipsis voiced stops in e.g. ar an gcasúr and radical voiced stops in e.g. an gadaí is likely to be due to the fact that the stop is preceded by [

]-less variant of the article occurs far more frequently after prepositions than when no preposition is present. Because the authors were unable to control for this, any difference in average burst intensity between eclipsis voiced stops in e.g. ar an gcasúr and radical voiced stops in e.g. an gadaí is likely to be due to the fact that the stop is preceded by [ ] far more frequently in the radical context than in the eclipsis context.

] far more frequently in the radical context than in the eclipsis context.

Venturing outwith Celtic, some Austronesian languages display a morphophonological process known as nasal substitution, which resembles the initial mutations of the Celtic languages. In an ultrasound study of Javanese and Sasak, Archangeli et al. (2017) compare the articulation of nasal [ɲ] from radical /s/ to that of nasal [ɲ] from radical / /, while Seyfarth et al. (2019) investigate whether Javanese [m ŋ] from radical /p k/ differ acoustically from non-alternating [m ŋ]. No statistically significant effect is found in either case.

/, while Seyfarth et al. (2019) investigate whether Javanese [m ŋ] from radical /p k/ differ acoustically from non-alternating [m ŋ]. No statistically significant effect is found in either case.

Welby et al. (2017:131–132) also cite two cases from the existing descriptive literature of what they refer to as “incomplete neutralisation” in initial mutation. First of all, Falc’hun (1951) reports for the Bas-Léon dialect of Breton that [b1 d1 g1] representing radical /b d g/ (e.g. dour [d1uːr] ‘water’) are longer and have stronger release bursts than [b2 d2 g2] from lenition of /p t k/ (e.g. dour [d2uːr] ‘tower’, radical tour [tuːr]). However, what Falc’hun is describing here is part of a phonological contrast between fortis and lenis consonants that pervades almost the entire consonant system of the dialect in question, whereby all radical initial consonants are fortis and are thus considerably longer and more strongly articulated than the lenis consonants that result from lenition (see also Falc’hun 1943:43–44; Kervella 1947; Hamp 1951; Carlyle 1988). The distinction is readily perceptible to native speakers and it appears unlikely that phonological neutralisation is involved in the first place. In any case, the difference is in the opposite direction to what would be expected under incomplete neutralisation.Footnote 1 Secondly, Borgstrøm (1940) and Oftedal (1956) report for the Lewis dialect of Scottish Gaelic that [m1

] representing radical /m

] representing radical /m  ɲ/ (e.g. mara [m1aɾə] ‘sea.gen’) are fully nasal while [m2

ɲ/ (e.g. mara [m1aɾə] ‘sea.gen’) are fully nasal while [m2

ɲ2] from nasalisation of /p

ɲ2] from nasalisation of /p  tj/ (e.g. am bara [ə m2aɾə] ‘the wheelbarrow’, radical bara [paɾə] ‘wheelbarrow’) are post-stopped. However, given that the distinction is so great as to be readily perceptible by fieldworkers, it is again unlikely that phonological neutralisation is involved. It is also somewhat doubtful that nasalisation of initial stops in Scottish Gaelic should be regarded as part of the initial mutation system, rather than as a purely phonological process of sandhi between a nasal consonant and a following word-initial stop. There is therefore no convincing evidence so far for incomplete neutralisation in initial mutation.

tj/ (e.g. am bara [ə m2aɾə] ‘the wheelbarrow’, radical bara [paɾə] ‘wheelbarrow’) are post-stopped. However, given that the distinction is so great as to be readily perceptible by fieldworkers, it is again unlikely that phonological neutralisation is involved. It is also somewhat doubtful that nasalisation of initial stops in Scottish Gaelic should be regarded as part of the initial mutation system, rather than as a purely phonological process of sandhi between a nasal consonant and a following word-initial stop. There is therefore no convincing evidence so far for incomplete neutralisation in initial mutation.

2.3 Vowel nasalisation in Scottish Gaelic

The primary focus of this study is the interaction of vowel nasalisation with an initial mutation in Scottish Gaelic. During the production of a nasalised vowel, the velum is lowered as for a nasal consonant and a proportion of the pulmonic egressive airstream is allowed to escape through the nasal cavity rather than through the mouth. Nasalisation may be measured experimentally in a number of ways, some more invasive or impractical than others (see Krakow and Huffman 1993 for a detailed discussion). Krakow (1989, 1993) measures the degree of opening of the velopharyngeal port using the Velotrace, a mechanical device that is inserted through the nose and directly records the position of the velum (Horiguchi and Bell-Berti 1987), while Solé (1992, 1995) employs a nasograph, a photoelectric device inserted through the nose and into the oesophagus (Ohala 1971). More recently, Byrd et al. (2009), Proctor et al. (2013), Carignan et al. (2015) and Barlaz et al. (2018) use real-time magnetic resonance imaging to directly observe velic and other articulatory movements during the production of nasalised vowels. It is also possible to measure nasalisation acoustically by spectral analysis (e.g. Chen 1996, 1997; Beddor 2007; Carignan et al. 2011; Shosted et al. 2012; Li 2014; Zellou and Tamminga 2014; Scarborough et al. 2015; Cho et al. 2017; Seyfarth et al. 2019), although the effect of nasalisation on formant values is often complex. An uninvasive, highly practical technique involves measuring the rate of nasal airflow at the nostrils in order to obtain an indirect measure of velic opening (e.g. Cohn 1990, 1993; Huffman 1990; Jun 1993; Basset et al. 2001; Shosted 2006; Delvaux et al. 2008; Carignan et al. 2011; Shosted et al. 2012; Carignan 2013; Li 2014; Warner et al. 2015; Desmeules-Trudel and Brunelle 2018). This is the technique employed in this study.

The issue of nasalisation in Scottish Gaelic has previously been investigated in a nasal airflow study by Warner et al. (2015). A nasalised fricative [ṽ], and occasionally other nasalised fricatives, have been claimed to occur in Scottish Gaelic (e.g. Ternes 1973; MacAulay 1992; Ó Maolalaigh 2003), but the authors conclude that true nasalised (non-glottal) fricatives are virtually non-existent in Scottish Gaelic. This study, however, is concerned with the nasalisation of vowels. Vowel nasalisation in Scottish Gaelic is a fairly complex issue. Stressed vowels may occasionally be phonemically nasalised, usually as a result of the historical deletion or de-nasalisation of an adjacent nasal consonant. Note that all Scottish Gaelic forms cited in this paper have initial stress, so we are concerned with the first syllable in every case:

-

(3)

amhaich

[ãfəxj]

‘neck’

cnoc

[khɾõhk]

‘hill’

cumhang

[khũ.ək]

‘narrow’

dannsa

[

]

]‘dance’

faic

[fẽhkj]

‘see’

grànda

[

]

]‘ugly’

làmh

[

]

]‘hand’

langa

[

]

]‘ling’

Additionally, Borgstrøm reports for Barra (1937:78–79) and Bernera in Lewis (1940:13) that all vowels are “more or less” nasalised when adjacent to nasal consonants. However, this is disputed by Oftedal (1956:40) for Leurbost in Lewis, Ternes (1973:126–127) for Applecross in Ross-shire, Dorian (1978:57) for East Sutherland, and Wentworth (2005:52) for Gairloch in Ross-shire, all of whom find that nasalisation may be contrastive on stressed vowels even next to nasal consonants. Ternes—who is also acquainted with the dialects of Barra and Lewis—concludes that Borgstrøm’s account is simply incorrect, and this is further supported by my own fieldwork in Ness in Lewis. Although stressed vowels are usually strongly nasalised when preceded by a nasal consonant, there are a number of items with preceding [m] in which this fails to occur:

-

(4)

a.

Nasalised vowel

b.

Non-nasalised vowel

madainn

[

]

]‘morning’

marag

[maɾak]

‘pudding’

màthair

[mãːhəðj]

‘mother’

marbhadh

[maɾa.əɣ]

‘killing’

meur

[mĩãɾ]

‘finger’

morghan

[mɔɾɔɣan]

‘gravel’

mias

[

]

]‘basin’

muilinn

[muljəɲ]

‘mill’

In the systems described by Oftedal (1956), Ternes (1973), Dorian (1978) and Wentworth (2005), the same contrast may potentially occur after other nasal consonants, as well as before a following nasal consonant. However, this study will consider only vowels preceded by [m], which is the only one of these environments where I am certain that such a contrast exists in Ness.

There is no rule to determine when nasalisation will fail to occur after a nasal consonant. Oftedal (1956:42) notes a tendency for nasalisation to be blocked on vowels adjacent to rhotic consonants or in svarabhakti groups (stressed VCV sequences that are phonologically monosyllabic; see Morrison 2019), but plenty of counterexamples exist. Because nasalisation of a vowel after a nasal consonant appears to be the default case, I will assume in this paper that a phonological rule spreads [+nasal] from a nasal consonant onto a following vowel in forms such as madainn [ ] ‘morning’. However, just as stressed vowels may occasionally be lexically marked as [+nasal] in non-nasal environments, e.g. amhaich [ãfəxj] ‘neck’, I will assume that the stressed vowel in a form such as marag [maɾak] ‘pudding’ is lexically [−nasal]. This results in the lexically-specific blocking of the spreading rule that is observed in forms of this type. An alternative analysis would be to simply assume that there is no spreading rule, and that vowel nasalisation is lexical in all cases. The choice between these two analyses is of no major consequence to the conclusions of this paper—what will be important is that forms such as madainn have a nasalised vowel in their phonological surface representation, while forms such as marag do not.

] ‘morning’. However, just as stressed vowels may occasionally be lexically marked as [+nasal] in non-nasal environments, e.g. amhaich [ãfəxj] ‘neck’, I will assume that the stressed vowel in a form such as marag [maɾak] ‘pudding’ is lexically [−nasal]. This results in the lexically-specific blocking of the spreading rule that is observed in forms of this type. An alternative analysis would be to simply assume that there is no spreading rule, and that vowel nasalisation is lexical in all cases. The choice between these two analyses is of no major consequence to the conclusions of this paper—what will be important is that forms such as madainn have a nasalised vowel in their phonological surface representation, while forms such as marag do not.

In a pilot version of this study, based on different data from a single speaker (S1 in this study; see Morrison 2018), it was shown instrumentally that nasal airflow in items like madainn [ ] ‘morning’ is sustained at an elevated level throughout the duration of the vowel. Meanwhile, items like marag [maɾak] ‘pudding’ display a small amount of rapidly decreasing nasal airflow early in the vowel. The probable occurrence of a small amount of nasalisation even in forms of the latter type was acknowledged by Ternes (1973:126) based on universal phonetic considerations. Following Cohn (1990, 1993) I interpret the plateau-like pattern of nasalisation in the former type as representing categorical phonological nasalisation, and the cline-like pattern in the latter as gradient phonetic nasalisation—which occurs without exception after a nasal consonant whenever phonological nasalisation fails to occur. Throughout this paper I mark categorical phonological nasalisation with a tilde in the transcription, while gradient phonetic nasalisation is left unmarked.

] ‘morning’ is sustained at an elevated level throughout the duration of the vowel. Meanwhile, items like marag [maɾak] ‘pudding’ display a small amount of rapidly decreasing nasal airflow early in the vowel. The probable occurrence of a small amount of nasalisation even in forms of the latter type was acknowledged by Ternes (1973:126) based on universal phonetic considerations. Following Cohn (1990, 1993) I interpret the plateau-like pattern of nasalisation in the former type as representing categorical phonological nasalisation, and the cline-like pattern in the latter as gradient phonetic nasalisation—which occurs without exception after a nasal consonant whenever phonological nasalisation fails to occur. Throughout this paper I mark categorical phonological nasalisation with a tilde in the transcription, while gradient phonetic nasalisation is left unmarked.

Under the lenition mutation in Scottish Gaelic, radical initial /p m/ (orthographically <b m>) both become [v] (orthographically <bh mh>). Note that radical initial /v/ does not occur in native lexical roots; however, like other “lenited” consonants, non-alternating initial /v/ can occur outwith lenition contexts in function words (e.g. bha [vaː] ‘be.pst’), loanwords (e.g. bhòt [ ] ‘vote’), placenames (e.g. Bhaltos [

] ‘vote’), placenames (e.g. Bhaltos [ ] ‘Valtos’) and some irregular verb forms (e.g. bheir [veðj] ‘give.npst.indep’). When items such as madainn [

] ‘Valtos’) and some irregular verb forms (e.g. bheir [veðj] ‘give.npst.indep’). When items such as madainn [ ] ‘morning’—in which the following vowel displays categorical phonological nasalisation—are lenited, the vowel remains strongly nasalised, e.g. mhadainn [

] ‘morning’—in which the following vowel displays categorical phonological nasalisation—are lenited, the vowel remains strongly nasalised, e.g. mhadainn [ ], and a variable amount of nasal airflow may also occur during [v] itself (Morrison 2018; cf. Warner et al. 2015). The first part of this word is therefore quite different to the first part of bhadan [

], and a variable amount of nasal airflow may also occur during [v] itself (Morrison 2018; cf. Warner et al. 2015). The first part of this word is therefore quite different to the first part of bhadan [ ] ‘thicket’, radical badan [

] ‘thicket’, radical badan [ ]. Since this nasalisation can be taken to be phonological, this is not an example of incomplete neutralisation. It is instead an example of paradigm uniformity at the level of categorical phonology: whether the mediating mechanism be cyclicity or OO-correspondence, the vowel of lenited mhadainn [

]. Since this nasalisation can be taken to be phonological, this is not an example of incomplete neutralisation. It is instead an example of paradigm uniformity at the level of categorical phonology: whether the mediating mechanism be cyclicity or OO-correspondence, the vowel of lenited mhadainn [ ] is phonologically nasalised as a result of its paradigmatic relationship with radical madainn [

] is phonologically nasalised as a result of its paradigmatic relationship with radical madainn [ ].

].

However, when items such as marag [maɾak] ‘pudding’—in which the following vowel displays only gradient phonetic nasalisation—are lenited, no nasalisation appears to remain, e.g. mharag [vaɾak]. The first part of this word is therefore apparently identical to the first part of bhara [vaɾə] ‘barrow’, radical bara [paɾə]. Any detectable difference between the first parts of these words would be an example of incomplete neutralisation. Under such a scenario, the fine-grained phonetic detail of mharag [vaɾak] and bhara [vaɾə] could be said to be influenced by their paradigmatic relationships with their respective radical forms. I now present an experiment that searches for such phonetic paradigm uniformity effects in order to determine whether incomplete neutralisation occurs in connection with initial mutation in Scottish Gaelic.

3 Experiment

In this section I report on a nasal airflow study that was carried out on four speakers of Scottish Gaelic from Ness, Lewis in order to determine whether lenition of radical initial /p m/ to [v] in Scottish Gaelic brings about incomplete neutralisation. The aims of the experiment are discussed in §3.1, the methods in §3.2 and the results in §3.3.

3.1 Aims

If categorical phonological nasalisation, but not gradient phonetic nasalisation, is sensitive to the paradigmatic relationship that exists between radical and lenited forms, it follows that the degree of nasalisation on the vowel following the initial [v] of a lenited form may be conditioned only by whether or not the vowel displays categorical phonological nasalisation in the corresponding radical form. It will not be conditioned by the presence or absence of gradient phonetic nasalisation in the radical form—i.e. by whether the initial consonant of the radical form is [p] or [m]. In other words, forms such as bhara [vaɾə] ‘barrow’ and mharag [vaɾak] ‘pudding’—neither of which displays categorical phonological nasalisation in its radical form—will display, ceteris paribus, the same degree of nasalisation on the vowel as one another, even though the former alternates with a form in initial [p] and the latter with a form in initial [m]. Likewise, the degree of nasalisation on initial [v] itself—if any occurs at all—will also be conditioned only by the presence or absence of categorical nasalisation on the vowel of the corresponding radical form.

On the other hand, if gradient phonetic nasalisation is sensitive to paradigmatic relationships, the degree of nasalisation on the vowel of the lenited form will additionally be conditioned by the identity of the corresponding radical consonant. In other words, the vowel of mharag [vaɾak] may display slightly greater nasal airflow than that of bhara [vaɾə] as a result of the presence of gradient phonetic nasalisation in its radical form. Similarly, the degree of nasalisation on initial [v] itself may also be affected.

Under the former scenario, only the presence or absence of categorical phonological nasalisation in the radical form of a given lexical item will act as a significant predictor of the degree of nasalisation in its lenited form; under the latter scenario, however, the identity of the initial radical consonant will also play a significant role. The first aim of this experiment is therefore to test whether the degree of nasalisation on either the vowel of a lenited form, or on initial [v] itself, is sensitive only to the presence of categorical phonological nasalisation in the corresponding radical form, or whether it is additionally sensitive to the identity of the corresponding radical consonant.

Since many of the most widely studied examples of incomplete neutralisation relate to durational differences, it is also plausible that such effects might be found in the duration of initial [v]. Indeed, a cursory analysis of a separate data set (part of which is used in Morrison 2018) shows that initial [p] in Scottish Gaelic is on average around 1.3 times longer than initial [m] (t(230.21)=−12.81, p<.001). The second aim of this experiment is therefore to test whether the duration of the initial [v] of a lenited form is sensitive to the identity of the corresponding radical consonant.

3.2 Methods

3.2.1 Speakers

Four male speakers aged 65–74 took part in the experiment. All were native speakers of Scottish Gaelic who were raised in Ness, Lewis by Scottish Gaelic-speaking parents from the same area. All were living in Ness at the time of recording and used Scottish Gaelic on a daily basis, although speakers S1 and S4 had both spent a large proportion of their adult lives living on the Scottish mainland. All four were sufficiently literate in Scottish Gaelic to carry out the experimental task without difficulty.

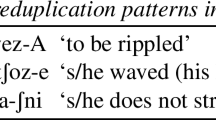

3.2.2 Word list

16 lexical items—all either nouns or verbal nouns—were chosen for the target stimuli, of which eight began with radical /p/ and eight with radical /m/. The items in /m/ included four that were believed, based on auditory impression, to have categorical phonological nasalisation on the following vowel, and four that were believed to have only gradient phonetic nasalisation. Each item was presented both in its radical form, with initial [p m], and in its lenited form, with initial [v]. In the latter case, the item was embedded in either a prepositional phrase or a progressive verb phrase and lenition was triggered by either the preposition a [ə], the dative singular definite article a’ [ə], the 2nd person singular possessive particle do [ ] or the formally identical 2nd person singular object particle. The resulting 32 target items are shown in Table 1. Note that the items in /p/ and /m/ constitute eight near-minimal pairs matched for the quality of the following vowel and, for the most part, the consonant following that vowel.Footnote 2

] or the formally identical 2nd person singular object particle. The resulting 32 target items are shown in Table 1. Note that the items in /p/ and /m/ constitute eight near-minimal pairs matched for the quality of the following vowel and, for the most part, the consonant following that vowel.Footnote 2

The target items were mixed with an equal number of filler items beginning with initial radical [ph kh k kjh kj f] and corresponding lenited [f x ɣ xj j Ø]. The 32 target items and 32 fillers were presented to each speaker in a printed word list. Each form occurred six times in the word list, making 384 items in total. Because the software being used allowed recording only in 10 s clips, these 384 items were split into 64 blocks of six and no carrier sentence was used. The items were randomised for each speaker, except for the following conditions:

-

Alternate blocks each contained either only radical forms or only lenited forms. Because the stimuli containing lenited forms are considerably longer than those containing radical forms, this was felt necessary in order to allow the speaker to settle into a comfortable rhythm for each block.

-

Within each block, the first, third and fifth items were target items while the second, fourth and sixth were fillers. This ensured that forms with the same initial consonant could not occur consecutively, while minimising the likelihood of a target item being lost off the end of a clip.

-

The word list consisted of six equally-sized parts such that each form occurred exactly once in each. This ensured that the six repetitions of each form were spread relatively evenly throughout the list.

3.2.3 Recording

Recording was carried out using the PCquirer X16 multi-channel data acquisition system produced by Scicon R&D, Inc. The setup includes a nasal airflow mask which is attached by a flexible plastic tube to a transducer containing a built-in microphone. The transducer passes audio and nasal airflow data in two channels to the X16 system, which is in turn connected to a computer via a USB port. The system outputs an analogue in mV of air pressure or airflow rate.

Before the mask was placed on each speaker, a 10 s clip of zero airflow was recorded in order to determine the degree of DC-offset in the signal. Each speaker was then recorded reading aloud from the word list while wearing the nasal airflow mask. In accordance with the limitations of the software, each block of six items was recorded in one 10 s clip. However, to ensure that the speaker proceeded at a comfortable pace, they were not informed of the 10 s time limit for each block. It was expected that the speaker would usually finish all six items before the recording ended, although the loss of a small proportion of items was considered inevitable.

For radical forms of target items, all 384 potential tokens were successfully collected (96 from each speaker). For lenited forms of target items, 375 tokens were successfully collected (92 from S1, 93 from S2, 96 from S3 and 94 from S4). Eight tokens were lost due to the speaker failing to produce all three target items in the block within the 10 s time limit (four from S1, three from S2 and one from S4). One further lenited token from S4 was discounted due to the unexpected pronunciation of bheul ‘mouth’ with a monophthong [ ] instead of a diphthong [

] instead of a diphthong [ ]. A handful of other unexpected pronunciations were admitted into the data set as they were of no consequence to the study, such as the pronunciation of the progressive particle ga as [ka], in line with orthography, rather than the usual Lewis form [ɣa].

]. A handful of other unexpected pronunciations were admitted into the data set as they were of no consequence to the study, such as the pronunciation of the progressive particle ga as [ka], in line with orthography, rather than the usual Lewis form [ɣa].

3.2.4 Analysis

The recordings were segmented in Praat (Boersma 2001) using the audio track in order to determine the boundaries of the vowel following initial [p m] in radical forms, and the boundaries of both initial [v] and the following vowel in lenited forms (initial [p m] in radical forms were not segmented, since this would be impractical without a carrier sentence and comparison of these sounds is not of interest to the present study). A Praat script was then used to extract values for nasal airflow at one-16th intervals throughout each of these segments, including endpoints, resulting in 17 data points for each radical token and 33 for each lenited token. For each speaker, the DC-offset determined at the beginning of the session was subtracted from all values. The system was calibrated using the CAL220 calibration device produced by Scicon R&D, Inc. in order to convert the output in mV of the nasal aiflow channel into values for nasal airflow rate expressed in ml / s. Linear mixed effects (LME) modelling was then carried out in R (R Core Team 2017), using the lme4 package (Bates et al. 2015), in order to determine what factors condition the degree of nasalisation on the vowel following the initial [v] of lenited forms, the degree of nasalisation on [v] itself, and the duration of initial [v].

3.3 Results

3.3.1 Categorical and gradient patterns of nasalisation

Dynamic nasal airflow profiles for both radical and lenited forms, obtained by averaging across all tokens at each timepoint, were plotted in order to confirm the type of nasalisation displayed by each of the items used in this study. These are shown in Fig. 1, arranged in near-minimal pairs with items in /p/ on the left and those in /m/ on the right. Turning first to radical forms, all those in /p/ display no clear nasalisation, while all those in /m/ display some nasalisation. Nasal airflow in madainn [ ], màthair [mãːhəðj], meur [mĩãɾ] and mias [

], màthair [mãːhəðj], meur [mĩãɾ] and mias [ ] falls rapidly after [m] but is sustained at a fairly high level throughout the duration of the following vowel, although the exact level varies due to the greater oral impedance in high vowels than low vowels (cf. e.g. Cohn 1990; Huffman 1990; Li 2014). This effect is especially clear when comparing the low vowel of màthair [mãːhəðj], in which nasal airflow is relatively low throughout, with the opening diphthongs of meur [mĩãɾ] and mias [

] falls rapidly after [m] but is sustained at a fairly high level throughout the duration of the following vowel, although the exact level varies due to the greater oral impedance in high vowels than low vowels (cf. e.g. Cohn 1990; Huffman 1990; Li 2014). This effect is especially clear when comparing the low vowel of màthair [mãːhəðj], in which nasal airflow is relatively low throughout, with the opening diphthongs of meur [mĩãɾ] and mias [ ], in which nasal airflow is higher during the first part of the diphthong and then falls to a level closer to that of màthair [mãːhəðj] for the second part. Vowel length may also play a role, with the short low vowel of madainn [

], in which nasal airflow is higher during the first part of the diphthong and then falls to a level closer to that of màthair [mãːhəðj] for the second part. Vowel length may also play a role, with the short low vowel of madainn [ ] displaying considerably higher nasal airflow than the long low vowel of màthair [mãːhəðj]. Although the exact level of nasal airflow varies according to factors such as these, it is clear that the vowels of these four forms are nasalised throughout their entire duration. I take this as confirmation that these four lexical items display categorical phonological nasalisation. On the other hand, nasal airflow in marag [maɾak], marbhadh [maɾa.əɣ], morghan [mɔɾɔɣan] and muilinn [muljəɲ] falls rapidly after [m] and continues to fall to zero. I take this as confirmation that these four lexical items display only gradient phonetic nasalisation.

] displaying considerably higher nasal airflow than the long low vowel of màthair [mãːhəðj]. Although the exact level of nasal airflow varies according to factors such as these, it is clear that the vowels of these four forms are nasalised throughout their entire duration. I take this as confirmation that these four lexical items display categorical phonological nasalisation. On the other hand, nasal airflow in marag [maɾak], marbhadh [maɾa.əɣ], morghan [mɔɾɔɣan] and muilinn [muljəɲ] falls rapidly after [m] and continues to fall to zero. I take this as confirmation that these four lexical items display only gradient phonetic nasalisation.

Dynamic nasal airflow profiles of radical and lenited forms. 0 in normalised time marks the beginning of the initial consonant, 1 marks the end of the initial consonant and the beginning of the following vowel, and 2 marks the end of the vowel (note that only the vowel is shown for radical forms—airflow during [p] can be assumed to be approximately zero, and airflow during [m] to be higher than 100 ml/s)

Turning now to lenited forms, items in radical /p/ generally show little to no nasalisation, although a certain amount of nasal aiflow does sporadically occur during [v] in some items—especially before short low vowels. Those items in radical /m/ that display categorical phonological nasalisation in their radical forms, i.e. mhadainn [ ], mhàthair [vãːhəðj], mheur [vĩãɾ] and mhias [

], mhàthair [vãːhəðj], mheur [vĩãɾ] and mhias [ ], display clear nasalisation on the vowel and, in the case of mhadainn [

], display clear nasalisation on the vowel and, in the case of mhadainn [ ]—where [v] is followed by a short low vowel—a considerable amount of nasal airflow during [v] itself. On the other hand, those items in radical /m/ that display only gradient phonetic nasalisation in their radical forms, i.e. mharag [vaɾak], mharbhadh [vaɾa.əɣ], mhorghan [vɔɾɔɣan] and mhuilinn [vuljəɲ], display similar profiles to items in radical /p/. This is consistent with the findings of Morrison (2018).

]—where [v] is followed by a short low vowel—a considerable amount of nasal airflow during [v] itself. On the other hand, those items in radical /m/ that display only gradient phonetic nasalisation in their radical forms, i.e. mharag [vaɾak], mharbhadh [vaɾa.əɣ], mhorghan [vɔɾɔɣan] and mhuilinn [vuljəɲ], display similar profiles to items in radical /p/. This is consistent with the findings of Morrison (2018).

3.3.2 Degree of nasalisation in lenited forms

The degree of nasalisation on (i) the vowel following the initial [v] of lenited forms and (ii) initial [v] itself is shown in Fig. 2. In those items with categorical nasalisation on the vowel of the corresponding radical form, a high degree of nasal airflow occurs during the vowel of the lenited form and some may also occur during [v]. In those items without categorical nasalisation in the corresponding radical form, nasal airflow is approximately zero in both the vowel and [v].

LME models were fitted to account for the degree of nasalisation on the vowel following the initial [v] of lenited forms. The dependent variable was the mean nasal airflow in ml / s across all 17 timepoints in the vowel (including endpoints) for each token. The null model contained fixed effects of categorical nasalisation (whether or not there is categorical phonological nasalisation in the corresponding radical form; two levels: yes, no) and vowel (six levels: [a], [aː], [ia], [iə], [ɔ], [u]), and random intercepts in speaker and stimulus. The alternative model was identical except for the additional fixed effect of radical consonant (the identity of the corresponding radical consonant; two-levels: /p/, /m/). A likelihood ratio test (LRT) was carried out in order to determine whether the alternative model performed significantly better than the null model. No significant difference was found (\(\chi ^{2}(1) = 1.23\), p = .267). This suggests that the identity of the corresponding radical consonant has no significant effect on the degree of nasalisation on the vowel following the initial [v] of lenited forms.Footnote 3

Similar LME models were fitted to account for the degree of nasalisation on initial [v] itself. This time, the dependent variable was the mean nasal airflow in ml / s across all 17 timepoints in [v] (including endpoints) for each token. All fixed and random effects were unchanged. Once again, an LRT was carried out in order to determine whether the alternative model performed significantly better than the null model. No significant difference was found (\(\chi ^{2}(1) = 2.21\), p = .137). This suggests that the identity of the corresponding radical consonant has no significant effect on the degree of nasalisation on the initial [v] of lenited forms.

3.3.3 Duration of initial [v] in lenited forms

The duration of the initial [v] of lenited forms is shown in Fig. 3. The duration appears to be similar across all conditions. Similar LME models were fitted, this time with the duration in ms of [v] for each token as the dependent variable. All fixed and random effects were again unchanged. Once again, an LRT was carried out in order to determine whether the alternative model performed significantly better than the null model. No significant difference was found (\(\chi ^{2}(1) = 0.058\), p = .809). This suggests that the identity of the corresponding radical consonant has no significant effect on the duration of the initial [v] of lenited forms.

4 Discussion

Incomplete neutralisation has been reported many times in Indo-European languages in connection with processes such as final devoicing, American English t/d-flapping and Russian unstressed vowel reduction, as well as in languages with very different morphological systems such as Chinese languages and Arabic. However, the few recent studies that have searched for incomplete neutralisation in initial mutation have found no convincing evidence for the phenomenon, and this study provides further evidence that it does not occur. Given that it is often observed in connection with other processes, the lack of any evidence for incomplete neutralisation in initial mutation raises the question of what makes initial mutation different. It might be suggested that mutational paradigms are structured in the mental lexicon in a fundamentally different manner to paradigms involving straightforwardly concatenative morphological processes. However, psycholinguistic experiments by Boyce et al. (1987) for Welsh and Ussishkin et al. (2017) for Scottish Gaelic have shown that the priming effects that different mutation grades of a single lexical item have on one another are similar to those observed between morphologically related forms in languages such as English. Schluter (2013) and Ussishkin et al. (2015) find similar results for Moroccan Arabic and Maltese respectively, which share a different kind of typologically unusual non-concatenative morphology based on consonantal templates.

One possibility is that radical forms occur less frequently than mutated forms and therefore do not act as a derivational base for mutated forms. However, mutated forms make up only 13.8% of tokens in the CEG corpus of written Welsh (Ellis et al. 2001). As for Scottish Gaelic specifically, the DASG corpus of Scottish Gaelic literature allows us to obtain a rough estimate of the relative token frequencies of radical and lenited forms. Among words beginning with those consonants for which lenition is marked orthographically, i.e. by insertion of a following <h>, the initial consonant is followed by <h> in 33.3% of tokens in the corpus, suggesting that radical forms are almost exactly twice as frequent as lenited forms. Moreover, this figure is probably skewed in favour of lenited forms by the existence of a number of very high-frequency function words beginning with non-alternating, inherently “lenited” consonants such as tha [haː] ‘be.prs’, bha [vaː] ‘be.pst’ and the negative particle cha [xa], so it is likely that radical forms outnumber lenited forms to an even greater degree among ordinary alternating lexical items. The lack of incomplete neutralisation in mutated forms is therefore probably not due to the relative token frequencies of radical and mutated forms.

A potential articulatory explanation for the lack of incomplete neutralisation in the lenition of /p m/ in Scottish Gaelic is that it would require nasalisation to occur on or adjacent to a fricative [v]. It is well-documented that fricatives (with an oral articulation forward of the velopharyngeal port) tend to be incompatible with nasalisation cross-linguistically, which Ohala (1975) and Ohala and Ohala (1993) ascribe to the articulatory challenge of producing sufficient oral airflow for frication to occur while simultaneously allowing air to escape through the nasal cavity. However, the presence of nasal airflow during [v] in mhadainn, shown in Fig. 1, suggests that this sound is quite amenable to nasalisation in Scottish Gaelic, and the results clearly show that it does not generally prevent nasalisation from occurring on a following vowel. In their nasal airflow study of putative nasalised fricatives in Scottish Gaelic, Warner et al. (2015) find that nasalisation, when it does occur during the articulation of the consonant, tends to co-incide with approximant-like realisations with no clear oral frication. It is therefore likely that [v] in Scottish Gaelic is not consistently articulated as a true fricative, and is thus not incompatible with nasalisation.

The majority of reported cases of incomplete neutralisation concern underlying contrasts that are faithfully represented in orthography (e.g. German Rat vs. Rad), and there is evidence that the presence of incomplete neutralisation, or at least the degree of incompleteness that occurs, is dependent upon the salience of orthographic forms during elicitation (Fourakis and Iverson 1984; Jassem and Richter 1989; Warner et al. 2004, 2006; Kharlamov 2012, 2014). However, Kharlamov (2012:194–195; 2014:54) raises the possibility that orthography may play a role even when it is completely absent from the experimental set-up, citing evidence that orthographic representations form part of the grammatical knowledge of literate speakers (Tanenhaus et al. 1980; Treiman and Danis 1988; Ziegler and Ferrand 1998). If this is the case, then the strength of orthographic representations in a speaker’s mental lexicon may affect the degree of incomplete neutralisation that occurs irrespective of the manner in which tokens are elicited. Since most speakers of minority languages like Scottish Gaelic (and other Celtic languages) receive relatively little exposure to the written language, it is highly probable that orthography would be far more weakly represented in the lexicons of speakers of those languages than for speakers of major national languages like Dutch, German, Polish and Russian. Although the spelling of [v] in Scottish Gaelic betrays its underlying radical form (e.g. bhara vs. mharag) just like neutralised final obstruents in German, such a difference in the strengths of orthographic representations in the mental lexicon could go part of the way to explaining why no convincing evidence has yet been found for incomplete neutralisation in initial mutation. Hall (2017:14) raises a similar point with respect to the absence of orthographic effects in Levantine Arabic. However, it is unlikely that this alone could account for the different patterns observed.

Seyfarth et al. (2019) make the generalisation that incomplete neutralisation is restricted to cases where word-specific morphological pressures come into conflict with language-wide phonotactic constraints, based on their finding that it does not occur in connection with Javanese nasal substitution. In the case of final devoicing, the morphological requirement that a word such as German Rad /ʀaːd/ ‘wheel’ have a voiced final obstruent is pitched against a phonotactic requirement that word-final obstruents be voiceless, resulting in incomplete neutralisation with Rat /ʀaːt/ ‘advice’. However, the neutralisation of the initial consonants of words such as Scottish Gaelic marag /maɾak/ ‘pudding’ and bara /paɾa/ ‘wheelbarrow’ in lenition contexts is driven not by phonotactic constraints but by the morphology itself. There is no general phonotactic ban on initial [v] in Scottish Gaelic, so no conflict occurs.Footnote 4 The results of this study are therefore consistent with Seyfarth et al.’s generalisation.

Relatedly, Hall (2017) suggests that incomplete neutralisation may be restricted to highly transparent, phonetically natural processes rather than more deeply morphologised ones. This conclusion is based on the differing properties of two phonological processes affecting vowels in Levantine Arabic, only one of which appears to bring about incomplete neutralisation. While Gouskova and Hall (2009) and Hall (2013) find subtle differences between underlying vowels and epenthetic vowels in Levantine Arabic, Hall (2017) finds no difference between underlyingly short vowels and underlyingly long vowels that have undergone a process of closed-syllable shortening. Hall ascribes this difference to the fact that vowel epenthesis in Levantine Arabic is a highly transparent process that serves to break up surface consonant clusters, while closed-syllable shortening occurs deeper in the phonology and interacts opaquely with morphological processes. While final devoicing in languages such as German can be regarded as highly transparent and phonetically natural, the alternations that occur as a result of initial mutation are directly tiggered by morphological processes and have no phonetic motivation. The negative results here and in other recent studies of initial mutation could thus be taken as further evidence in favour of Hall’s claim.

If it is true that incomplete neutralisation is restricted to highly transparent, phonetically natural processes in which word-specific morphological pressures come into conflict with language-wide phonotactic constraints, this nevertheless does not appear to be a sufficient condition for its occurrence. Complete neutralisation has also been reported in connection with some processes that meet these criteria, such as manner neutralisation in coda consonants in Korean (Kim and Jongman 1996). Neutralisation of stem-final /t th s/ to [t] in coda position applies transparently and reflects the typologically common tendency for codas to permit fewer consonantal contrasts than onsets. Unless a vowel-initial suffix triggers resyllabification, the morphological requirement that a particular stem end in /th/ or /s/ comes into conflict with a phonotactic requirement that neither of these consonants occur in coda position. If Kim and Jongman’s (1996) conclusion is correct, then it remains unclear why incomplete neutralisation should fail to occur in connection with this process.

Finally, a possible explanation for the lack of incomplete neutralisation in the lenition of /p m/ in Scottish Gaelic becomes apparent when the phonetic correspondences involved are considered at the gestural level. Most, possibly all, of the cases of incomplete neutralisation reported thus far can be regarded as paradigmatic effects on the timing and/or magnitude of corresponding articulatory gestures that are shared between morphologically related forms. For instance, the successive vocalic and closure gestures in German Rad [ʀaːt] ‘wheel’ have direct correspondents in the genitive form Rades [ʀaːdes]. However, the phonological plan for mharag [vaɾak] ‘pudding’ requires no velum-lowering gesture corresponding to that which produces nasalisation in the radical form marag [maɾak]. Rather, the occurrence of phonetic nasalisation in the former would require the addition of a velum-lowering gesture that would not otherwise be present in this form. Whatever the mechanism that lies behind phonetic paradigm uniformity effects, one possibility is that their occurrence is dependent upon the presence of corresponding articulatory gestures in morphologically related forms.

5 Conclusion

The existence of incomplete neutralisation continues to pose a challenge to strictly modular feedforward architectures of grammar. However, in order to determine exactly to what extent these theories must be modified in order to account for such phenomena, it is necessary to build a more complete picture of the precise circumstances that may bring about incomplete neutralisation. There remain many questions to be answered about the kinds of morphological alternations in which incomplete neutralisation may or may not occur, but this paper has reviewed the small number of existing studies of incomplete neutralisation in connection with one typologically unusual type of morphology and provided further evidence that the neutralisations it brings about are complete. These results help to bring us closer to an understanding of the structure of the mental lexicon and the processes that lie behind the derivation of morphologically complex forms.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that they have no conflict of interest.

Notes

The item b(h)uilgean was erroneously spelled as *b(h)uiligean in the printed word lists.

Because nasalisation in the radical forms of items such as marag [maɾak] is mostly confined to approximately the first half of the vowel, it could be suggested that averaging across the entire vowel might mask the presence of a significant effect early in the vowel. However, repeating the analysis using only those timepoints located in the first half of the vowel likewise reveals no significant effect (\(\chi ^{2}(1) = 0.77\), p = .381).

Although radical initial /v/ does not occur in native lexical roots in Scottish Gaelic, recall from §2.3 that non-alternating initial /v/ may still freely occur in function words, loanwords, placenames and some irregular verb forms.

References

Archangeli, D., Johnston, S., Sung, J.-H., Fisher, M., Hammond, M., & Carnie, A. (2014). Articulation and neutralization: A preliminary study of lenition in Scottish Gaelic. In H. Li & P. Ching (Eds.), Proceedings of the 15th Annual Conference of the International Speech Communication Association (INTERSPEECH 2014), Singapore, 14th–18th September 2014 (pp. 1683–1687).

Archangeli, D., Yip, J., Qin, L., & Lee, A. (2017). Phonological and phonetic properties of nasal substitution in Sasak and Javanese. Laboratory Phonology, 8(1), 1–27.

Ball, M. J., & Müller, N. (1992). Mutation in Welsh. London: Routledge.

Barlaz, M., Shosted, R., Fu, M., & Sutton, B. (2018). Oropharyngeal articulation of phonemic and phonetic nasalization in Brazilian Portuguese. Journal of Phonetics, 71, 81–97.

Baroni, M., & Vanelli, L. (2000). The relationship between vowel length and consonantal voicing in Friulian. In L. Repetti (Ed.), Phonological theory and the dialects of Italy (Current issues in linguistic theory 212) (pp. 13–44). Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Barry, S. M. E. (1988). Temporal aspects of the devoicing of word-final obstruents in Russian. In W. A. Ainsworth & J. N. Holmes (Eds.), Speech ’88: Proceedings of the 7th FASE Symposium (Vol. 1, pp. 81–88). Edinburgh: Institute of Acoustics.

Basset, P., Amelot, A., Vaissière, J., & Roubeau, B. (2001). Nasal airflow in French spontaneous speech. Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 31(1), 87–99.

Bates, D., Mächler, M., Bolker, B., & Walker, S. (2015). Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software, 67(1), 1–48.

Beddor, P. S. (2007). Nasals and nasalization: The relation between segmental and coarticulatory timing. In J. Trouvain & W. J. Barry (Eds.), Proceedings of the 16th International Congress of Phonetic Sciences (pp. 249–254).

Benua, L. (1997). Transderivational identity: Phonological relations between words. PhD dissertation, University of Massachusetts.

Bermúdez-Otero, R. (2011). Cyclicity. In M. van Oostendorp, C. J. Ewen, E. Hume, & K. Rice (Eds.), The Blackwell companion to Phonology 4: Phonological interfaces (pp. 2019–2048). Oxford: Blackwell.

Boersma, P. (2001). Praat, a system for doing phonetics by computer. Glot International, 5(9/10), 341–345.

Borgstrøm, C. Hj. (1937). The dialect of Barra in the Outer Hebrides. Norsk Tidsskrift for Sprogvidenskap, 8, 71–242.

Borgstrøm, C. Hj. (1940). The dialects of the Outer Hebrides. In A Linguistic Survey of the Gaelic Dialects of Scotland (Vol. 1). Oslo: Norwegian Universities Press.

Boyce, S., Browman, C. P., & Goldstein, L. (1987). Lexical organization and Welsh consonant mutations. Journal of Memory and Language, 26(4), 419–452.

Braver, A. (2011). Incomplete neutralization in American English flapping: A production study. University of Pennsylvania Working Papers in Linguistics, 17(1), 31–40.

Braver, A. (2013). Degrees of incompleteness in neutralization: Paradigm uniformity in a phonetics with weighted constraints. PhD dissertation, State University of New Jersey.

Braver, A. (2014). Imperceptible incomplete neutralization: Production, non-identifiability, and non-discriminability in American English flapping. Lingua, 152, 24–44.

Braver, A. (2019). Modelling incomplete neutralisation with weighted phonetic constraints. Phonology, 36(1), 1–36.

Bybee, J. (2001). Phonology and language use. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Byrd, D., Tobin, S., Bresch, E., & Narayanan, S. (2009). Timing effects of syllable structure and stress on nasals: A real-time MRI examination. Journal of Phonetics, 37(1), 97–110.

Carignan, C. M. (2013). When nasal is more than nasal: The oral articulation of nasal vowels in two dialects of French. PhD dissertation, University of Illinois.

Carignan, C., Shosted, R. K., Fu, M., Liang, Z.-P., & Sutton, B. P. (2015). A real-time MRI investigation of the role of lingual and pharyngeal articulation in the production of the nasal vowel system of French. Journal of Phonetics, 50, 34–51.

Carignan, C., Shosted, R., Shih, C., & Rong, P. (2011). Compensatory articulation in American English nasalized vowels. Journal of Phonetics, 39(4), 668–682.

Carlyle, K. A. (1988). A syllabic phonology of Breton. PhD dissertation, University of Toronto.

Charles-Luce, J. (1985). Word-final devoicing in German: Effects of phonetic and sentential contexts. Journal of Phonetics, 13, 309–324.

Charles-Luce, J., & Dinnsen, D. A. (1987). A reanalysis of Catalan devoicing. Journal of Phonetics, 15(2), 187–190.

Chen, M. Y. (1996). Acoustic correlates of nasality in speech. PhD dissertation, MIT.

Chen, M. Y. (1997). Acoustic correlates of English and French nasalized vowels. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 102(4), 2360–2370.

Cho, T., Kim, D., & Kim, S. (2017). Prosodically-conditioned fine-tuning of coarticulatory vowel nasalization in English. Journal of Phonetics, 64, 71–89.

Cohn, A. C. (1990). Phonetic and phonological rules of nasalization. In: UCLA working papers in phonetics (Vol. 76).

Cohn, A. C. (1993). Nasalisation in English: phonology or phonetics. Phonology, 10(1), 43–81.

DASG = Corpas na Gàidhlig: Digital Archive of Scottish Gaelic. University of Glasgow. Available online at https://dasg.ac.uk/corpus/.

Delvaux, V., Demolin, D., Harmegnies, B., & Soquet, A. (2008). The aerodynamics of nasalization in French. Journal of Phonetics, 36(4), 578–606.

Desmeules-Trudel, F., & Brunelle, M. (2018). Phonotactic restrictions condition the realization of vowel nasality and nasal coarticulation: Duration and airflow measurements in Québécois French and Brazilian Portuguese. Journal of Phonetics, 69, 43–61.

Dinnsen, D. A., & Charles-Luce, J. (1984). Phonological neutralization, phonetic implementation and individual differences. Journal of Phonetics, 12, 49–60.

Dmitrieva, O., Jongman, A., & Sereno, J. (2010). Phonological neutralization by native and non-native speakers: The case of Russian final devoicing. Journal of Phonetics, 38(3), 483–492.

Dorian, N. C. (1978). East Sutherland Gaelic: The dialect of the Brora, Golspie and Embo fishing communities. Dublin: Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies.

Ellis, J. (1965). The grammatical status of initial mutation. Lochlann, 3, 315–329.

Ellis, N. C., O’Dochartaigh, C., Hicks, W., Morgan, M., & Laporte, N. (2001). Cronfa Electroneg o Gymraeg (CEG): A 1 million word lexical database and frequency count for Welsh. Bangor University. Available online at https://www.bangor.ac.uk/canolfanbedwyr/ceg.php.en.

Ernestus, M., & Baayen, R. H. (2006). The functionality of incomplete neutralization in Dutch: the case of past-tense formation. In L. Goldstein, D. H. Whalen, & C. T. Best (Eds.), Phonology and Phonetics: Vol. 4-2. Laboratory phonology 8 (pp. 27–49). Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Ernestus, M., & Baayen, R. H. (2007). Intraparadigmatic effects on the perception of voice. In J. van de Weijer & E. Jan van der Torre (Eds.), Current Issues in Linguistic Theory: Vol. 286. Voicing in Dutch: (De) voicing—phonology, phonetics, and psycholinguistics (pp. 153–174). Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Ewen, C. J. (1982). The phonological representation of the Welsh mutations. In J. Anderson (Ed.), Language form and linguistic variation (pp. 75–95). Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Falc’hun, F. (1943). La langue bretonne et la linguistique moderne. Paris: Librairie Celtique.

Falc’hun, F. (1951). Le système consonantique du breton avec une étude comparative de phonétique expérimentale. Annales de Bretagne, 57(1), 5–194.

Fisher, W. M., & Hirsh, I. J. (1976). Intervocalic flapping in English. In S. S. Mufwene, C. A. Walker, & S. B. Steever (Eds.), Papers from the 12th regional meeting: Chicago Linguistic Society (pp. 183–198). Chicago: Chicago Linguistic Society.

Fourakis, M., & Iverson, G. K. (1984). On the ‘incomplete neutralization’ of German final obstruents. Phonetica, 41, 140–149.

Fox, R. A., & Terbeek, D. (1977). Dental flaps, vowel duration and rule ordering in American English. Journal of Phonetics, 5, 27–34.

Gouskova, M., & Hall, N. (2009). Acoustics of epenthetic vowels in Lebanese Arabic. In S. Parker (Ed.), Phonological argumentation: Essays on evidence and motivation (pp. 203–225). London: Equinox.

Green, A. D. (2006). The independence of phonology and morphology: The Celtic mutations. Lingua, 116(11), 1946–1985.

Hall, N. (2013). Acoustic differences between lexical and epenthetic vowels in Lebanese Arabic. Journal of Phonetics, 41(2), 133–143.

Hall, N. (2017). Phonetic neutralization in Palestinian Arabic vowel shortening, with implications for lexical organization. Glossa, 2(1). Art. 48.

Hamp, E. P. (1951). Morphophonemes of the Keltic mutations. Language, 27(3), 230–247.

Hannahs, S. J. (2013). Celtic initial mutation: Pattern extraction and subcategorisation. Word Structure, 6(1), 1–20.

Herd, W., Jongman, A., & Sereno, J. (2010). An acoustic and perceptual analysis of /t/ and /d/ flaps in American English. Journal of Phonetics, 38(4), 504–516.

Horiguchi, S., & Bell-Berti, F. (1987). The Velotrace: A device for monitoring velar position. The Cleft Palate Journal, 24, 104–111.

Huffman, M. K. (1990). Implementation of Nasal: Timing and articulatory landmarks. In: UCLA working papers in phonetics (Vol. 75).

Iosad, P. (2014). The phonology and morphosyntax of Breton mutation. Lingue e Linguaggio, 13(1), 23–42.