Abstract

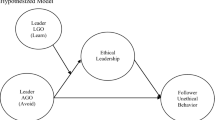

This paper brings empirical and theoretical studies of ethical leadership into conversation with one another in an effort to determine the antecedent(s) to perceived ethical leadership. Employing a Levinasian perspective, I argue that ethical leadership entails being faced with the impossible task of realizing the needs of many individual others. For this reason, I argue, perceived ethical leadership is grounded in an employee’s perception that a leader struggles to make decisions based on the conflicting demands placed upon her. More important than the result of a leader’s decision is the degree to which the leader demonstrates concern for the well-being of others in her decision-making process. I ground my discussion through reference to results of empirical studies on behaviors associated with ethical leadership, including Brown, Treviño, and Harrison (2005), Kalshoven, Den Hartog, and De Hoogh (2011a), and Treviño, Hartman, and Brown (2000). I identify several mediating factors which may influence employee perception of ethical leadership, proposing avenues for further research which can help to clarify the relationship between concrete leadership behaviors and perceived ethical leadership.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

For further discussion of how Levinas’ conception of personal responsibility can be brought to bear on our understanding of maintaining ethical relationships in a business environment, see Tajalli and Segal (2019). For the implications of the Levinasian conception of justice with regard to the institutional issues of whistleblowing and restorative justice, see Loumansky and Lewis (2013) and Faldetta (2019), respectively. Trezise and Biesta (2009), meanwhile, offer a pedagogical perspective on the role of Levinasian relationships in contemporary management ethics.

The term “transformative” is not agreed upon by all scholars working in the field. Burns (1978), for example, employs the phrase “transforming” leadership, whereas Avolio and Bass defend a conception of “transformational” leadership. While each term registers different connotations, I use transformative to generally refer to this constellation of views without taking a stance regarding the appropriateness of one term over the others, an issue which extends beyond the scope of this discussion.

Notably, Mayer et al. (2012) set out to demonstrate, and provide research in support of, the idea that a leader’s moral identity – i.e. how she sees herself and regulates her behavior based on internalized notions of right and wrong – is a significant antecedent to perceived ethical leadership (p. 152). This is an important finding, but it also raises the question of what it means for a leader to identify herself as moral. Furthermore, it leads to the question of how and in what sense employees perceive the moral identity of their leaders. Thus, on its own, the study doesn’t provide a clear answer to the question of the cause of perceived ethical leadership.

For the purpose of efficiency, I focus here on the leadership behaviors of people orientation, empowerment, fairness (associated with trustworthiness and justice), and ethical guidance. Related arguments can be made that role clarification, integrity, and concern for sustainability are grounded in the perception of ethical deliberation, but a more thorough analysis of these conditions is reserved for a separate discussion.

For further phenomenological analysis of the first-personal experience of trust, see Steinbock (2014).

There exists significant literature establishing the connection between religious beliefs and personal values with respect to workplace behavior and maintaining professional relationships; see, for example, Kamoche and Pinnington (2012); Smallwood (2002); and Karjalainen, Islam, and Holm (2019). Relatedly, Mayer et al. (2012) suggest that employees are more likely to emulate the behavior of ethical role models than unethical ones insofar as they observe what types of behavior are expected of them. These studies provide evidence in support of the suggestion that there may be a significant relationship between role models, previous leader-follower relationships, and perceived ethical leadership.

Evidence that suggests there may be a significant relationship between perceived workplace ethical cultures and perceived ethical leadership can be found in: Brown and Mitchell (2010), who argue that employees tend to reciprocate ethical leadership with higher levels of ethical behavior and citizenship behaviors and are less likely to engage in destructive behavior such as workplace deviance; Tanner et al. (2010) and Demirtas et al. (2017), who demonstrate a positive correlation between perceived ethical leadership behavior and organizational identification and commitment; and Walumbwa et al. (2011), who demonstrate that organizational identification and leader-member exchange mediate the relationship between perceived ethical leadership and task performance, suggesting that an employee whom a leader treats well is likely to want to perform well in return, to reciprocate prosocial behavior, and to exert effort on the behalf of the perceived ethical supervisor.

Indirect evidence of a negative correlation between perceived ethical leadership and preferential treatment can be found in Kannan-Narasimhan and Lawrence (2012), who demonstrate that behavioral integrity – alignment between leaders’ words and deeds – has a positive influence on organizational citizenship behavior. This suggests that a leader’s failure to live up to professed notions of fairness can lead to the perception that the leader has failed to “walk the talk.” Thau et al. (2013), meanwhile, demonstrate that group members who receive preferential behavior are more likely to engage in prosocial behavior than those who are treated equally to their peers; however, their study does not look at the effects of perceived preferential treatment on the behavior of employees who do not receive that treatment. For a relevant discussion of the effects of leader-follower conflict on employees’ behaviors and attitudes towards one another, see Yang (2020).

References

Arnett, Ronald C. 2003. The responsible “I”: Levinas’s derivative argument. Argumentation and Advocacy 40: 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/00028533.2003.11821596.

Avolio, B.J., and B.M. Bass. 1995. Individual consideration viewed at multiple levels of analysis: A multi-level framework for examining the diffusion of transformational leadership. The Leadership Quarterly 6: 199–218. https://doi.org/10.1016/1048-9843(95)90035-7.

Bevan, David, and Hervé Corvellec. 2007. The impossibility of corporate ethics: For a Levinasian approach to managerial ethics. Business Ethics: A European Review 16: 208–219. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8608.2007.00493.x.

Brown, Michael E., and Marie S. Mitchell. 2010. Ethical and unethical leadership: Exploring new avenues for future research. Business Ethics Quarterly 20: 583–616. https://doi.org/10.5840/beq201020439.

Brown, Michael E., Linda K. Treviño, and David A. Harrison. 2005. Ethical leadership: A social learning perspective for construct development and testing. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 97: 117–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2005.03.002.

Burns, James MacGregor. 1978. Leadership. New York, NY: Harper & Row.

Byers, Damian, and Carl Rhodes. 2007. Ethics, alterity, and organizational justice. Business Ethics: A European Review 16: 239–250. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8608.2007.00496.x.

Cheong, Minyoung, Seth M. Spain, Francis J. Yammarino, and Seokhwa Yun. 2016. Two faces of empowering leadership: Enabling and burdening. The Leadership Quarterly 27: 602–616. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2016.01.006.

Cheong, Minyoung, Francis J. Yammarino, Shelley D. Dionne, Seth M. Spain, and Chou-Yu Tsai. 2019. A review of the effectiveness of empowering leadership. The Leadership Quarterly 30: 34–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2018.08.005.

Ciulla, Joanne B. 2004. Leadership ethics: Mapping the territory. In Ethics, the heart of leadership, ed. Joanne B. Ciulla, 3–24. Westport, CT: Praeger.

Ciulla, Joanne B. 2005. The state of leadership ethics and the work that lies before us. Business Ethics: A European Review 14: 323–335. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8608.2005.00414.x.

Crevani, Lucia, Monica Lindgren, and Johann Packendorff. 2010. Leadership, not leaders: On the study of leadership as practices and interactions. Scandinavian Journal of Management 26: 77–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scaman.2009.12.003.

Cropanzano, Russell, and Marie S. Mitchell. 2005. Social exchange theory: An interdisciplinary review. Journal of Management 31: 874–900. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206305279602.

Dansereau, Fred, Francis J. Yammarino, Steven E. Markham, Joseph A. Alutto, Jerry Newman, MacDonald Dumas, Sidney A. Nachman, Thomas J. Naughton, Kyongsu Kim, Saad A. Al-Kelabi, Sangho Lee, and Tiffany Keller. 1995. Individualized leadership: A new multiple-level approach. The Leadership Quarterly 6: 413–450. https://doi.org/10.1016/1048-9843(95)90016-0.

Demirtas, Ozgur, Sean T. Hannah, Kubilay Gok, Aykut Arslan, and Nejat Capar. 2017. The moderated influence of ethical leadership, organizational identification, and envy. Journal of Business Ethics 145: 183–199. https://doi.org/10.1007/s1055101529077.

Faldetta, Guglielmo. 2019. When relationships are broken: Restorative justice under a Levinasian approach. Philosophy of Management 18: 55–69. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40926-018-0094-1.

Frisch, Colina, and Markus Huppenbauer. 2014. New insights into ethical leadership: A qualitative investigation of the experiences of executive ethical leaders. Journal of Business Ethics 123: 23–43. https://doi.org/10.1007/s1055101317979.

Geyer, Alois L.J., and Johannes M. Steyrer. 1998. Transformational leadership and objective performance in banks. Applied Psychology: An International Review 47: 397–420. https://doi.org/10.1080/026999498377917.

Gilligan, Carol. 1995. Moral orientation and moral development. In Justice and care: Essential readings in feminist ethics, ed. Virginia Held, 31–46. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Hartog, Den, N. Deanne, and Annebel H.B. De Hoogh. 2009. Empowering behaviour and leader fairness and integrity: Studying perceptions of ethical leader behaviour from a levels-of-analysis perspective. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology 18: 199–230. https://doi.org/10.1080/13594320802362688.

Jones, Jen. 2014. Leadership lessons from Levinas: Revisiting responsible leadership. Leadership and the Humanities 2: 44–63. https://doi.org/10.4337/lath.2014.01.04.

Kalshoven, Karianne, Deanne N. Den Hartog, and Annebel H.B. De Hoogh. 2011a. Ethical leadership at work questionnaire (ELW): Development and validation of a multidimensional measure. The Leadership Quarterly 22: 51–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2010.12.007.

Kalshoven, Karianne, Deanne N. Den Hartog, and Annebel H.B. De Hoogh. 2011b. Ethical leader behavior and big five factors of personality. Journal of Business Ethics 100: 349–366. https://doi.org/10.1007/s1055101006859.

Kamoche, Ken, and Ashly H. Pinnington. 2012. Managing people ‘spiritually’: A Bourdieusian critique. Work, Employment and Society 26: 497–513. https://doi.org/10.1177/0950017012438573.

Kannan-Narasimhan, Rangapriya, and Barbara S. Lawrence. 2012. Behavioral integrity: How leader referents and trust matter to workplace outcomes. Journal of Business Ethics 111: 165–178. https://doi.org/10.1007/s1055101111999.

Karjalainen, Mira, Gazi Islam, and Marie Holm. 2019. Scientization, instrumentalization, and commodification of mindfulness in a professional services firm. Organization. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350508419883388.

Keller, Robert T. 2006. Transformational leadership, initiating structure, and substitutes for leadership: A longitudinal study of Research and Development project team performance. Journal of Applied Psychology 91: 202–210. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.91.1.202.

Knights, David, and Majella O’Leary. 2006. Leadership, ethics and responsibility to the other. Journal of Business Ethics 67: 125–137. https://doi.org/10.1007/s1055100690086.

Levinas, Emmanuel. 1969. Totality and infinity: An essay on exteriority, trans. Alphonso Lingis. Pittsburgh, PA: Duquesne University Press.

Liu, Helena. 2017. Reimagining ethical leadership as a relational, contextual and political practice. Leadership 13: 343–367. https://doi.org/10.1177/1742715015593414.

Loumansky, Amanda, and David Lewis. 2013. A Levinasian approach to whistleblowing. Philosophy of Management 12 (3): 27–48. https://doi.org/10.5840/pom201312317.

Maak, Thomas, and Nicola M. Pless. 2006. Responsible leadership in a stakeholder society – A relational perspective. Journal of Business Ethics 66: 99–115. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-006-9047-z.

Mayer, David M., Karl Aquino, Rebecca L. Greenbaum, and Maribeth Kuenzi. 2012. Who displays ethical leadership, and why does it matter? An examination of antecedents and consequences of ethical leadership. Academy of Management Journal 55: 151–171. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2008.0276.

Pless, Nicola M., and Thomas Maak. 2011. Responsible leadership: Pathways to the future. Journal of Business Ethics 98: 3–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-011-1114-4.

Rhodes, Carl. 2012. Ethics, alterity and the rationality of leadership justice. Human Relations 65: 1311–1331. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726712448488.

Rhodes, Carl, and Richard Badham. 2018. Ethical irony and the relational leader: Grappling with the infinity of ethics and the finitude of practice. Business Ethics Quarterly 28 (1): 71–98. https://doi.org/10.1017/beq.2017.7.

Smallwood, John. 2002. Health and safety (H&S) and religion: Is there a link? Procs. Triennial conference CIB W099 implementation of safety and health on construction site. Hong Kong.

Solomon, Robert C. 1973. Emotions and Choice. The Review of Metaphysics, 27: 20–41. https://doi.org/revmetaph1973271156.

Solomon, Robert C. 2004. Ethical leadership, emotions, and trust: Beyond “charisma”. In Ethics, the heart of leadership, ed. Joanne B. Ciulla, 83–102. Westport, CT: Praeger.

Solomon, Robert C. 2005. Emotional leadership, emotional integrity. In The quest for moral leaders: Essays on leadership ethics, ed. Joanne B. Ciulla, Terry L. Price, and Susan E. Murphy, 28–44. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing. Retrieved from https://library-books24x7-com.avoserv2.library.fordham.edu/toc.aspx?site=EVYO8&bookID=22401.

Steinbock, Anthony J. 2014. Moral emotions: Reclaiming the evidence of the heart. Evanston, IL: Northwest University Press.

Tajalli, Payman, and Steven Segal. 2019. Levinas, weber, and a hybrid framework for business ethics. Philosophy of Management 18: 71–88. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40926-018-01007.

Tanner, Carmen, Adrian Brügger, Susan van Schie, and Carmen Lebherz. 2010. Actions speak louder than words: The benefits of ethical behaviors of leaders. Journal of Psychology 218: 225–233. https://doi.org/10.1027/0044-3409/a000032.

Thau, Stefan, Christian Tröster, Karl Aquino, Madan Pillutla, and David De Cremer. 2013. Satisfying individual desires or moral standards? Preferential treatment and group members’ self-worth, affect, and behavior. Journal of Business Ethics 113: 133–145. https://doi.org/10.1007/s1055101212875.

Treviño, Linda Klebe, Laura Pincus Hartman, and Michael Brown. 2000. Moral person and moral manager: How executives develop a reputation for ethical leadership. California Management Review 42 (4): 128–142. https://doi.org/10.2307/41166057.

Trezise, Edward, and Gert Biesta. 2009. Can management ethics be taught ethically? A Levinasian exploration. Philosophy of Management 8 (1): 43–54. https://doi.org/10.5840/pom20098137.

Walumbwa, Fred O., David M. Mayer, Peng Wang, Hui Wang, Kristina Workman, and Amanda L. Christensen. 2011. Linking ethical leadership to employee performance: The roles of leader-member exchange, self-efficacy, and organizational identification. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 115: 204–213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2010.11.002.

Yammarino, Francis J., Shelley D. Dionne, Jae Uk Chun, and Fred Dansereau. 2005. Leadership and levels of analysis: A state-of-the-science review. The Leadership Quarterly 16: 879–916. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2005.09.002.

Yang, Conna. 2020. How to avoid coworker relationship conflict: A study of leader-member exchange, value congruence, and workplace behavior. Asian Journal of Business Ethics. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13520-020-00099-3.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Steiner, C. The Influence of Demonstrated Concern on Perceived Ethical Leadership: A Levinasian Approach. Philosophy of Management 19, 447–467 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40926-020-00139-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40926-020-00139-9