Abstract

The many-property problem has traditionally been taken to show that the adverbial theory of perception is untenable. This paper first shows that several widely accepted views concerning the nature of perception—including both representational and non-representational views—likewise face the many-property problem. It then presents a solution to the many-property problem for these views, but goes on to shows how this solution can be adapted to provide a novel, fully compositional solution to the many-property problem for adverbialism. Thus, with respect to the many-property problem, adverbialism and several widely accepted views in the philosophy of perception are on a par, and the problem is solved.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

As we will see below, this category includes (i) all property representationalist views, (ii) relational views of perception on which we can be perceptually aware of uninstantiated properties, and (iii) views that treat the contents of perception as gappy.

Adverbialism about perception was originally defended by Ducasse (1942) and Chisholm (1956), and then later by Sellars (1975) and Tye (1975, (1984). For many years, however, most philosophers of perception treated adverbialism as untenable on its own terms, and thought that its benefits were available to other views—typically representationalist views. Recently, however, there has been some renewed discussion of adverbial views of perception and intentionality, for instance, by Kriegel (2007, (2008, (2011), Mendelovici (2018, Ch. 9), Banick (2018), Bourget (forthcoming), and D’Ambrosio (2019).

Adverbialism as a theory of perception is importantly distinct from adverbialism concerning other aspects of our mental lives, including qualia, the emotions, and attention. The form of adverbialism with which I am concerned is a view concerning the fundamental nature of perception.

On this traditional approach to forming complex adverbs, which is roughly the view given in Tye (1975), “(green-and-square)-ly” and (red-and-circular)-ly” are syntactic primitives. This is not a particularly plausible approach to the semantics of adverbial modification, since it is not compositional. Below, in solving the many-property problem, I will present a compositional way of forming such adverbs, but for the moment, in presenting the problem, I will make use of the traditional paraphrases.

The many-property problem was originally proposed by Jackson (1975). There have been numerous attempts to respond to it, including by Tye (1975, (1984, (1989), Sellars (1975), and more recently by Kriegel (2007, (2008). These attempts have met with resistance from Woodling (2016) and Grzankowski (2018), and have even occasioned a strengthening of the original problem due to Dinges (2015).

I choose Johnston’s view here for definiteness and clarity, but my arguments apply to any view of perception that involves the perceiving subject bearing a relation to an uninstantiated property, whether or not the relation is one of awareness, and whether or not the relation is representational. Such views are numerous. For instance, the view that in hallucinatory perceptual experience, we are aware of uninstantiated properties is held by Bealer (1982), Dretske (1999, (2003), Foster (2000), Forrest (2005), Johnston (2004), and Tye (2014a, (2014b), among others, although Johnston is not a representationalist. The view that in perception, we bear a relation that is not an awareness relation to uninstantiated properties is defended by Pautz (2007). The arguments also apply to the view that the contents of hallucination are gappy, defended by Tye (2009) and Schellenberg (2013, (2014), among others.

Johnston moves between these two different phrases. As we will see presently, this equivocation matters.

It is important to note that sensible profiles can include uninstantiated relations, such as the relation of being under. However, insofar as views such as Johnston’s allow uninstantiated relations to figure into the complex properties that we sense, such views also face the so-called “many-relations” problem, posed by Dinges (2015). As we will see, the solution I provide below solves both the many-property and many-relations problems for both property theories and adverbialism.

A type shift is a change in the type of semantic value that a semantic theory assigns to a particular expression, typically to correct for a mismatch between the argument-type accepted by a verb’s denotation and the type of semantic value assigned to its argument. The ordinary semantic value of a complex noun phrase such as “a green square and a red circle” is a generalized quantifier. In a standard Montagovian system, such a quantifier is intensional, and of type \(\langle s,\langle \langle s,\langle e,t \rangle \rangle , t\rangle \rangle \). In extensional theories, generalized quantifiers are of type \(\langle \langle e,t \rangle ,t\rangle \). We will see below how to shift an object of this type to the type of a property. See Hendriks (1993) for a systematic approach to type-shifting.

One way of bringing this out is to notice that despite the fact that (11) and (12) have structured properties as arguments, their logical form, at least in first-order logic, is still that of a simple binary relation; they both have the form V(Mary,P). In order to determine which inferences such sentences underwrite, we need principles that go beyond those in first-order logic: we need principles that tell us how structural relations between properties determine relations between states that relate us to those properties.

“Omits” is not the only verb for which such inference patterns fail: they also fail for verbs of resemblance, such as “resemble”, “imitate”, and “simulate”, and for verbs such as “lack”. It is a substantive question which intensional verbs validate adjective-drop inferences within their complements.

This argument begins to show, contra Bourget (2019), that inferences within the complements of intensional ascriptions cannot be purely formal. Which inferences hold within the complement of an intensional verb will depend on the lexical meaning of the verb in question. I will discuss this point further below. However, I agree with Bourget that inferences involving so-called “special quantifiers”, such as from “John wants a big dog” to “John wants something” are formal. This may well be due to the distinctive semantic features of “something”, which are outlined by Sainsbury (2018, Ch. 2). Sainsbury argues that “something” is substitutional.

See Schellenberg (2013, p. 304) for a clear statement of the view that illustrates the need for a solution to the many-property problem.

In what follows, I will continue to use Johnston’s view to illustrate my points, while noting that my arguments generalize to all property views.

Perhaps most basically, monotonicity inferences are the result of quantification; each quantifier has a so-called “monotonicity profile”: a distinctive collection of monotonicity inferences that it validates. See van Benthem (1984) for discussion. Propositional attitude verbs underwrite monotonicity inferences because on the standard semantics for such verbs, given by Hintikka (1962), propositional attitudes involve quantification over worlds: propositional attitude verbs are modals. Thus, it is common for semanticists to argue over the monotonicity profiles of intensional verbs. See Forbes (2006), Zimmermann (2006), von Fintel and Heim (Unpublished), and Rubinstein (2017) for discussion.

By considering only these two inference patterns, I am simplifiying the monotonicity problem significantly. The problem for intensional transitive verbs becomes much more complicated once disjunctive and quantified complements are introduced. However, this simplification is justified because these two patterns are the ones relevant to the case of perception, and the ones that form the basis of the traditional inferential problem for adverbialism. For further discussion of the monotonicity profile of intensional verbs, see Forbes (2006) and Sainsbury (2018).

Other intensional transitive verbs specify conditions appropriate to the kinds of activities they denote. For instance, desires may have satisfaction-conditions, debts may have discharge conditions, fears may have realization conditions, etc.

The analysis is called the “Quine–Hintikka Analysis” because it has its roots in Hintikka’s semantics for propositional attitude verbs, which validates upward monotonicity for propositional attitudes. Quine then proposed to decompose non-propositional attitude verbs into propositional attitude verbs in a way that would make them susceptible to Hintikka’s analysis.

This is analogous to inferences that arise in the complements of propositional attitude verbs, except that in the propositional case, instead of success-worlds, we considering worlds at which the proposition in question is true.

In fact, Hintikka’s original analysis secured upward monotonicity for all propositional attitude verbs, which leads to the problem of logical omniscience.

The only difference here is that \(\lambda x \lambda y[green'(x) \wedge square'(x) \wedge red'(y) \wedge circle'(y)\) is of type \(\langle e ,\langle e,t \rangle \rangle \), as opposed to type \(\langle e,t \rangle \). This is just a feature of the kind of properties that hold of two distinct objects.

Again, nothing turns on my choice of the verb “senses”. The exact same approach can be applied to “is perceptually aware of”, or any other perceptual verb that can express relations to uninstantiated properties.

However, there may also be a disanalogy here: findings temporally succeed, or are perhaps the culminations of, searches, whereas seeings do not seem to temporally succeed visual sensings.

Of course, the property representationalist might deny this because it treats relational seeing as fundamental in the analysis of perception. An alternative is to adopt a conjunctive analysis, and claim that sensings are accurate when the subject is appropriately causally related to what she senses. Formally, modifying the analysis in this way is trivial.

I say that these states are logically related because the analysis serves as an axiom from which the entailment relations between states of sensing can be derived. Here, “logical relations” does not mean relations of structural entailment.

For instance, in von Fintel and Heim [Unpublished, Ch. 2], the modal component of propositional attitude verbs is present in logical form. By contrast, on many accounts of the semantics of intensional transitive verbs, such as Zimmermann (2006), Forbes (2006), and Moltmann (2008), the modal component does not find its way into logical form, but remains at the lexical level.

The type-shift just presented, along with its subsequent explanation using the Quine–Hintikka analysis, is very similar to the analysis given by Forbes (2006, p. 82). The basic idea is to type-shift an entire quantified NP to the type of a modifier, and then to explain the behavior of the modifier using an “outcome postulate”, which employs the quantified NP in the ordinary way. The fact that the behavior of the modifier is ultimately explained in terms of an ordinary use of the quantified NP guarantees compositionality.

This kind of modification is even more common with noun-phrases: consider, for example, “duck-hunt”, “chicken-coop”, “three-story building”, “one-woman university” and “many-splendoured thing.” (The latter three examples come from Forbes (2006, p. 79).) In each of these examples, what was once an argument of a prepositional phrase comes to serve as an attributive adjective that restricts the denotation of the noun. The verbal modifier that is the output of (39) functions exactly analogously, except instead of taking a noun as an input, it takes a verb. Thus, we might call the outputs of our type shift “attributive adverbs.”

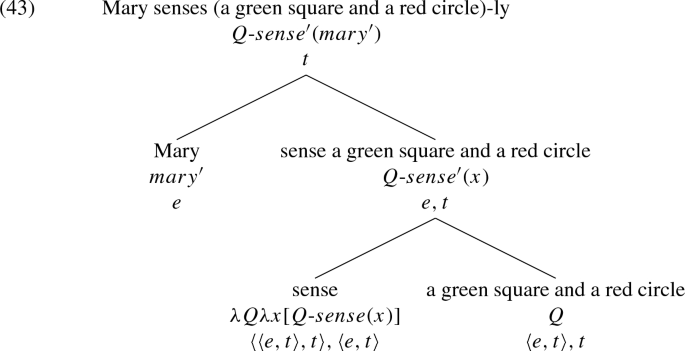

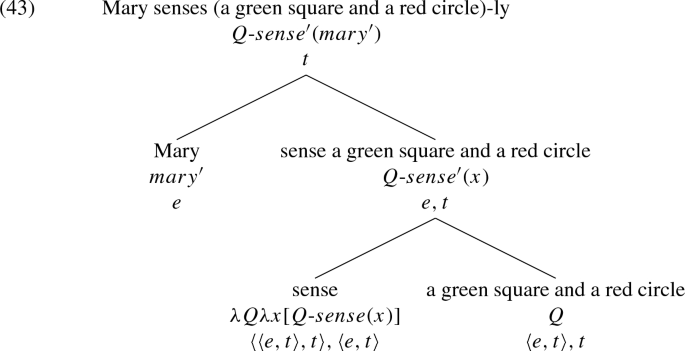

There is another way of deriving the same semantics compositionally without making use of a type-shift. The method is to treat “sense” as semantically incorporating its direct object argument—that is, treat it as on a par with verbs like “salmon-fish” or “duck-hunt”. On this method, instead of type-shifting the generalized quantifier that serves as the semantic value of the complement, we can type the incorporating verb so that it has a restrictor argument, as in (43):

This semantics is very similar to the one given by Dayal (2011, §6.4) for incorporating verbs in Hindi. We can then apply the Quine–Hintikka analysis to the result of this derivation to explain the behavior of the restrictor, and validate upward monotonicity. I have discussed the connection between semantic incorporation and adverbialism in other work (see D’Ambrosio 2019). For further discussion of semantic incorporation, see Carlson (2006); Dayal (2011); Borik and Gehrke (2015).

What I here call structural and non-structural approaches go by many names. Evans (1976) calls the structural entailment formal entailment, and contrasts it with semantic entailment. I follow Jackson (2007) in calling the former kind of entailment structural entailment, but while he calls the latter form lexical entailment, I call it non-structural entailment. I use the term “non-structural” because it avoids the implication that such entailments must be semantic. Non-structural entailments are relations of necessitation; they need not be lexical.

There are several different kinds of non-structural entailments that can hold between two states of the world A and B. A may a posteriori entail B, it may a priori entail B, or it may analytically entail B. Typically, these kinds of entailment are distinguished by the status of the strict conditional \(\Box A \rightarrow B\). If the conditional is a posteriori, the entailment is a posteriori. If the conditional is a priori, then the entailment is a priori. If the conditional is analytic, then the entailment is analytic.

In distinguishing between states of sensing only up to necessary equivalence of adverbial modifiers, this form of adverbialism is not hyperintensional. Accordingly, if a subject senses P-ly, and necessarily, all and only Ps are Qs, then the subject senses Q-ly. Further, it follows from the Quine–Hintikka analysis that if a subject senses anything, the subject senses the property of being self-identical (or any other property that everything has necessarily). These consequences are features of a possible-worlds approach to spelling out success-conditions, and are exactly analogous to the problems occasioned by the Hintikka analysis of propositional attitudes. However, there are well-known ways of addressing these problems. For one approach to hyperintensionality, see Forbes (2006, Ch. 8). For an attempt to solve the analogue of the logical omniscience problem, see Zimmermann (2006).

This point has been noted already by Alexander Dinges (2015, p. 233, n. 2); here I simply reiterate it. I am grateful to an anonymous referee for Philosophical Studies for rightly pointing this out.

References

Banick, K. (2018). How to be an adverbialist about phenomenal intentionality. Synthese. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-018-02053-0.

Bealer, G. (1982). Quality and concept. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Borik, O., & Gehrke, B. (Eds.). (2015). The syntax and semantics of pseudo-incorporation. Syntax and semantics. Leiden and Boston: Brill.

Bourget, D. (2019). Implications of intensional perceptual ascriptions for relationalism, disjunctivism, and representationalism about perceptual experience. Erkenntnis, 84(2), 381–408.

Bourget, D. (forthcoming). Relational vs adverbial conceptions of phenomenal intentionality. In A. Sullivan (Ed.), Sensations, thoughts, and language: Essays in honor of Brian Loar. London: Routledge.

Chisholm, R. (1956). Perceiving: A philosophical study. In D. Rosenthal (Ed.), The nature of mind, chapter 11. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

D’Ambrosio, J. (2019). A new perceptual adverbialism. Journal of Philosophy 116(8), 413–446. https://doi.org/10.5840/jphil2019116826.

Dayal, V. (2011). Hindi pseudo-incorporation. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory, 29(1), 123–167.

Dinges, A. (2015). The many-relations problem for adverbialism. Analysis, 75(2), 231–237.

Dretske, F. (1995). Naturalizing the mind. The Jean Nicod lectures. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

Dretske, F. (1999). The mind’s awareness of itself. Philosophical Studies, 95, 103–124.

Dretske, F. (2003). Experience as representation. Philosophical Issues, 13(1), 67–82.

Ducasse, C. J. (1942). Moore’s refutation of idealism. In P. Schilpp (Ed.), The philosophy of G.E. Moore (pp. 223–252). Chicago: Northwestern University Press.

Evans, G. (1976). Semantic structure and logical form. In Collected papers. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Forbes, G. (2006). Attitude problems. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Forrest, P. (2005). Universals as sense-data. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 71, 622–631.

Foster, J. (2000). The nature of perception. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Greg, C. (2006). The meaningful bounds of incorporation. In S. Vogeleer & L. Tasmowski (Eds.), Non-definiteness and plurality, Linguistics Today 95. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Grzankowski, A. (2018). The determinable-determinate distinction can’t save adverbialism. Analysis, 78(1), 45–52.

Hendriks, H. (1993). Studied flexibility. Ph.D. thesis, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam.

Hintikka, J. (1962). Knowledge and belief: An introduction to the logic of the two notions. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Jackson, B. B. (2007). Beyond logical form. Philosophical Studies, 132(2), 347–380.

Jackson, F. (1975). On the adverbial analysis of visual experience. Metaphilosophy, 6(2), 127–135.

Johnston, M. (2004). The obscure object of hallucination. Philosophical Studies, 120(1–3), 113–183.

Kriegel, U. (2007). Intensional inexistence and phenomenal intentionality. Philosophical Perspectives, 21(Philosophy of Mind), 307–340.

Kriegel, U. (2008). The dispensability of (merely) intentional objects. Philosophical Studies, 141, 79–95.

Kriegel, U. (2011). The veil of abstracta. Philosophical Issues, 21(The Epistemology of Perception), 245–267.

Mendelovici, A. (2018). The phenomenal basis of intentionality. New York: Oxford University Press.

Moltmann, F. (2008). Intensional verbs and their intentional objects. Natural Language Semantics, 16, 239–270.

Pautz, A. (2007). Intentionalism and perceptual presence. Philosophical Perspectives, 21, 495–541.

Pautz, A. (2010). Why explain visual experience in terms of content? In B. Nanay (Ed.), Perceiving the world (pp. 254–309). New York: Oxford University Press.

Rubinstein, A. (2017). Straddling the line between attitude verbs and necessity modals. In A. Salanova, A. Arregui, & M. L. Rivero (Eds.), Modality Across Syntactic Categories, chap 7. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Sainsbury, R. M. (2018). Thinking about things. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Schellenberg, S. (2013). Externalism and the gappy content of hallucination. In F. Macpherson & D. Platchias (Eds.), Hallucination: Philosophy and psychology. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Schellenberg, S. (2014). The relational and representational character of perceptual experience. In B. Brogaard (Ed.), Does perception have content? (pp. 199–219). New York: Oxford University Press.

Sellars, W. (1975). The adverbial theory of the objects of sensation. Metaphilosophy, 6(2), 144–160.

Tye, M. (1975). The adverbial theory: A defence of sellars against jackson. Metaphilosophy, 6(2), 136–143.

Tye, M. (1984). The adverbial aproach to visual experience. The Philosophical Review, 93(2), 195–225.

Tye, M. (1989). The metaphysics of mind. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Tye, M. (2009). Consciousness revisited: Materialism without phenomenal concepts. Representation and mind. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Tye, M. (2014a). What is the content of a hallucinatory experience? In B. Brogaard (Ed.), Does perception have content? chapter 10. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Tye, M. (2014b). Transparency, qualia realism and representationalism. Philosophical Studies, 170, 39–57.

van Benthem, J. (1984). Questions about quantifiers. Journal of Symbolic Logic, 49(2), 443–466.

von Fintel, K., & Heim, I. Intensional semantics. Lecture Notes, Cambridge, MA (Unpublished).

Woodling, C. (2016). The limits of adverbialism about intentionality. Inquiry, 59(5), 488–512.

Zimmermann, T. E. (2006). Monotonicity in opaque verbs. Linguistics and Philosophy, 29, 715–761.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to Daniel Stoljar for countless helpful discussions and written comments on earlier versions of this paper. Thanks also to Zoltán Gendler Szabó, Alex Grzankowski, David Papineau, Laura Gow, and Tim Crane for their helpful comments on various versions of this material.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

D’Ambrosio, J. The many-property problem is your problem, too. Philos Stud 178, 811–832 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-020-01459-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-020-01459-2