The historiography of mining has largely ignored mining women, as well as the wives of the miners.Footnote 1

Mining's tumultuous history evokes images of rootless, brawny and often militant men, whether laboring in sixteenth-century Peru or twenty-first-century South Africa.Footnote 2

This focus, on large, formally owned and operated, corporate capital mineral extraction processes, ignores how poor people actually live on mineral-rich tracts in the world. Peasant or informal mining and quarrying – digging, washing, sieving, panning and amalgamating – provide livelihood for at least 13 million people in the global south (ILO, 1999). Extracting low volumes of minerals from small and scattered deposits using little capital/technology, and with low labour cost, productivity and returns, is a worldwide phenomenon […].Footnote 3

The central argument in this Special Theme, and in this Introduction, is that in the history of mining the role of women as mineworkers and women as household workers has been overlooked. As early as 1993, Christina Vanja pointed out that the number of women working as miners was being underestimated, while in 2007 Laurie Mercier and Jaclyn Gier emphasized how mining has predominantly been associated with masculinity, and in 2012 Kuntala Lahiri-Dutt called into question the focus on big mining in mining history, which contributed to ignoring the role of women.Footnote 4 This erasure of women from the history of mining can be explained by the focus in the historiography on the implementation since the first decades of the nineteenth century of laws to protect women and children, resulting in a ban on and the exclusion of women and children from working in underground mines. This exclusion can also be explained by the dominance of the breadwinner model and an ideology that considered women primarily as mothers and reproducers of the labour force.

Taking a longer-term, global labour history perspective,Footnote 5 it is important to underline the fact that women were as active as miners in the past as they are in the present. The history of women as miners allows us to understand how state and employers’ policies contributed to masculinizing work and sites of labour by implementing protective laws. This was a process that ran parallel to what has been labelled the “de-labourization” of womenFootnote 6 since the eighteenth century: the development by which women were increasingly excluded from more or less formal wage labour employment by state and employer regulations, based on a male breadwinner ideology and the masculinization of workplaces and work processes. This tendency lasted until the mid-twentieth century, when, in the name of equality, protective laws came to be considered discriminatory against women; they were then increasingly dismantled. The process of masculinization was also concomitant with the development of a social welfare system in European countries, although it did not extend to the rest the world, where an increasing “informal economy” gained ground. The mining sector in the Global South was part of this process and it was women's informal work that extended throughout the mines. On a longer-term global scale, women were evicted from mining for a period of 150 to 200 years, to reappear in the present era, mainly in the Global South, but in the worst and most precarious conditions.

As a result of the protective laws and the exclusion of women from underground tasks, women's work became increasingly restricted to household work, while their pivotal role in reproduction and care work in mining communities was also insufficiently recognized. This process of “de-labourization” of women's work and the closely connected distinction made between productive and unproductive labour was in accordance with the classical political economy since Adam Smith, where unpaid care work and domestic activities were considered “unproductive” labour and underestimated.Footnote 7

Although opinions and attitudes towards women and mining were unequal in different societies around the globe,Footnote 8 domestic ideology in Europe and North America, originating from eighteenth- and nineteenth-century debates on “women's nature”, was adjusted to the particular circumstances of the Industrial Revolution, providing a moral rationale for keeping women out of the mines and at home. A domestic ideology and the male breadwinner ideology concealed the concrete meaning of the gender division of labour for women's work in mining households, as well as the value of women's unpaid labour to the mining industry.Footnote 9

In this Introduction, we will give an overview of the paid and unpaid labour of women in mines and in mining households, referring to cases that illuminate trends or transformations within regions in different national and colonial settings, and within a wide variety of minerals, though without pretending to be exhaustive. We will then introduce the three articles in this Special Theme and explain how each contributes to the main issues addressed here.

WOMEN AS MINEWORKERS

Mining is a complex process, and although different minerals have their own specificities generally speaking there are different production stages, starting with the extraction of ores in underground pits, or on the surface, going subsequently through different steps of mineral processing, i.e. the extraction of minerals underground or at the surface, and the process to obtain metals from ores through crushing/grinding, separation, dewatering, and drying. Looking closely at this whole production process, women played a more active role than is often thought. It is important to distinguish the various steps in order to analyse the division of labour by age and sex and to understand how laws affected underground mining and surface mining differently.

This Introduction aims first to foreground the importance of women as mineworkers in different parts of the world, and for the diverse minerals exploited, since the early modern period. Second, we focus on the changes introduced specifically in coal mining during the Industrial Revolution, throughout the nineteenth century, and in the first few decades of the twentieth century. Third, we aim to underline the growing importance of women in contemporary small-scale and artisanal mining, where they make up more than forty per cent of the workforce (compared with around ten per cent in large-scale mining).Footnote 10

Women at work between the end of the sixteenth and the end of the eighteenth centuries

In the early modern period, all over the world, work in mines was an activity performed by the family: men, women, and children. In Europe, various tasks crucial for the existence of mining communities were undertaken by women in underground mines and above ground. Vanja stated that mining could be a form of household enterprise similar to other crafts in such a way that, until the nineteenth century, teams of husbands and wives could be found working together.Footnote 11 Frequently, a gender division of labour existed: men were mainly hewers (as in the coal industry), while women would break ores and metals, rinsing, sorting, washing, hauling, and moving ores. Women also used to do various transport-related jobs, such as carrying wood and coal to heat the furnaces or transporting the cold iron. However, women received less pay: in the mid-sixteenth century, women's wages were only half those of men.Footnote 12 In early modern German mining, women were employed above ground in picking, sorting, hammering, and washing the ore. In coal mining, until 1892, the miners’ wives and children worked as drawers, pulling sledges or tubs to the bottom shaft, and as haulers.Footnote 13 In Britain, family work was also very common until the early nineteenth century, and women worked underground in the coal mines in family teams.Footnote 14 A recent study states that forty per cent of workers in Scottish mines were female, hauling and bearing coal, work that was a legacy of a system of serfdom.Footnote 15

In India, in the Golconda region, diamonds were also worked by the family. In the early seventeenth century, there were c.50,000 men digging pits, while women and children carried away the earth.Footnote 16 In Spanish America,Footnote 17 from the sixteenth to the eighteenth centuries the silver and gold mines doubled or tripled the world's stock of money.Footnote 18 An estimated 150,000 tons of silver were produced between 1500 and 1800, representing eighty per cent of the entire global production in this period.Footnote 19 Silver was directly worked by men. However, as Velasco noted, male work was underground, while female work above ground has been largely ignored.Footnote 20 Women were more present as mineworkers in the most important gold regions, such as New Granada (present-day Colombia) and Brazil. In Brazil, the gold rush of the eighteenth century brought slavery to the mines, rivalling the slave-sugar plantations. Although only men were portrayed as explorers, frontier settlers, and mine labourers,Footnote 21 female slaves were painted working on the rivers,Footnote 22 and as negras de Tabuleiro (escrava de ganho) or slave hawkers in Minas Gerais.Footnote 23 In what is today Colombia, gold extraction was mainly in the hands of the mine's gang overseers (señores de minas y cuadrillas) working with at least five slaves, led by a captain male slave or female slave in the case of female gangs.Footnote 24 Throughout the region of Antioquía and in the Chocó, the presence of women as workers is more evident. In Antioquía, gold was extracted by slave gangs (cuadrillas) and by independent peasant-miners called mazamorreros, comprising free slaves, mulattoes, and Indians.Footnote 25 The mazamorreros accounted for two thirds of the region's gold output in 1786.Footnote 26 They worked the mines with their family, but some of them could have owned slaves. In Cáceres, in 1796, twenty-four mines were worked by slaves, free day workers (jornaleros), and gangs comprising both slaves and free people. The slave population of 244 people was distributed among seven owners (two women), while there were 137 free workers distributed among twenty owners.Footnote 27 In the Chocó region, gold output between 1735 and 1799 accounted for between forty-five and seventy per cent of the total official gold produced in New Granada (Colombia). Here, gold exploitation was an important area of family work, including women and children. There were fewer than two men for every woman among working slaves; three decades later, women comprised more than forty-five per cent of all slaves. Particularly important in the region was the growing number of slaves who purchased their freedom.Footnote 28

From the end of the eighteenth century there were important changes. Christina Vanja describes how Europe's small mines were absorbed into larger, capitalistic enterprises, and women were excluded from every aspect of their operation.Footnote 29 In this sense, the mines’ masculinity was not the natural order, as Lahiri-Dutt reminds us.Footnote 30 Peter Alexander has noted that family labour was generally associated with manual labour in smaller mines, and that the removal of women was linked to mechanization and the pressure to produce more efficiently.Footnote 31

The exclusion of women seems to parallel the emergence and constitution of capitalism, considered here as a historical process of commodification that in global terms had different rhythms, and included diverse labour regimes and technological changes with different outcomes and results.Footnote 32 Several factors and variables need to be analysed in order to understand its links and connections to the history of mining in its varied manifestations: underground and surface mining; types of mineral; demand and prices; property rights and rules relating to exploitation; capital intensity or labour intensity; labour costs; labour organization and unions; type and size of enterprise; state intervention; ideologies; and gender relations. This complexity points to the need for more studies to identify and delineate a chronology, as well as the tendencies and specificities according to region and type of mineral. The case of coal mining in Great Britain is an example, and the prohibition on the work of women and children became more widespread across the world.

Laws to protect women in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries

In general, it is believed that there were at least two moments when women were excluded from mines in modern Europe: after 1842 and after 1930. However, it is important to make two qualifications here. On the one hand, according to Christina Vanja, by the eighteenth century women had largely disappeared from mining as part of a process of proletarianization in which mineworkers were transformed from small, independent, and petty producers into wage workers in large enterprises.Footnote 33 On the other hand, as we will see, the measures taken in Great Britain in 1842 extended throughout Europe and even the world. In this sense, the regulations adopted by the International Labour Organization (ILO) after 1930 formalized a situation in which, with just a few exceptions, women no longer worked in underground mines.

In 1800, Great Britain produced eighty per cent of the world's coal, and 118,233 men were employed in coal mining in England, Wales, and Scotland in 1841, while, according to official figures, only 2,350 women were, although the real figure might actually have been higher, between 5,000 and 6,000.Footnote 34 The Mines and Collieries Act of 1842 banning women and children from coal mines was adopted after an enquiry ordered by Queen Victoria. According to Angela John's analysis of the debate surrounding the Act, arguments were fuelled by the ambivalence of nineteenth-century attitudes towards the employment of working-class women, in which women miners were considered the very essence of degraded womanhood.Footnote 35 Alan Heesom asserted that the Act's protagonists and opponents had complex motivations. There was a humanitarian aspect inspired by religious attitudes to children's education; there was also an interest in combatting what was considered an indecent occupation for women (who might be naked in the pits); finally, it was one aspect of factory regulation.Footnote 36

Under the Mines and Collieries Act of 1842, all females under eighteen were required to leave underground employmentFootnote 37 within three months. Women had to search for another job, and some of them continued to work above ground as “pit brow lasses” or on platforms upon which the coal was sorted and screened.Footnote 38 These pit brow women were regarded as an aberration in a masculine domain, a contradiction of the bourgeois ideal of home, which tore women from the household and her “natural sphere”.Footnote 39 A similar situation could be found in coal mines in France and Belgium with the prohibition of underground work for women, who then continued to work on the surface.Footnote 40

The 1842 Act was considered “the first and one of the most extensively documented pieces of discriminatory labour legislation”,Footnote 41 and the first time that “authorities limited the exploitation of a class of workers on the basis of gender, a distinction which has characterized protective labour legislation ever since”.Footnote 42 In France, the Law of 1874 prohibited underground work for girls and women.Footnote 43

The Mines and Collieries Act of 1842 provided no financial compensation for women, forcing many to evade the law and placing some 5,000 women in a precarious situation.Footnote 44 It is in this context that women wore men's clothes in order to pass as men in the pits.Footnote 45

Women remained important in other parts of the world, such as India and Japan. In 1890, in India, around 25,000 labourers worked in Bengal's coal mines – a figure that had increased to 175,000 by 1919, while the number of women rose more rapidly than the number of men. Cutters working underground were predominantly men, while around 44 per cent of the loaders were women. In surface tasks, fifty-seven per cent of workers were men and thirty-five per cent women, the rest being children.Footnote 46 In the coalfields of Jharia and Raniganj in 1924, around fifty-five per cent of the women working underground worked with their husbands, thirty per cent worked with their relatives, and twenty per cent on their own. Again, there was a distinct gendered division of labour: men cut the coal while their wives and children carried and hauled it. This family work system could also be found in the Kyushu coal mines in southern Japan, where, since the mid-nineteenth century, men hewed and women hauled. Until World War I, family work, including women's work, was promoted by many mining companies. In 1909, in Japan, around ten per cent of all women employed worked in mines and collieries.Footnote 47 Women accounted for twenty-one per cent of all miners, seventeen per cent of those in metal mining, and twenty-five per cent of those in coal mining (Table 1).

Table 1. Males and females working in mining, Japan, 1909.

Source: Nimura Kazuo, The Ashio Riot of 1907: A Social History of Mining in Japan (Durham, NC, 1997), p. 17.

The numbers around 1924 are impressive because seventy-one per cent of women labourers were working underground.Footnote 48 There was also an existing culture of women's involvement in mines and working above ground, while men laboured underground. The traditional system was associated with men digging the coal while women transported it to the surface and sorted it outside.Footnote 49 There were, however, important regional differences even within Japan. In the Chikuho coal fields, husband and wife teams worked in the pits as coal diggers, and women accounted for thirty per cent of the pit workforce in the 1920s.Footnote 50

A second point at which women were excluded in much wider regions corresponds to the wave of legislation to protect women from the mid-nineteenth century to World War II. This period has to be understood in the context of escalating concerns in the West during the nineteenth and the early twentieth centuries about the impact of industrialization on the family lives of men and women. It is noteworthy that this new concern was combined with appeals to morality and the duties of motherhood, contributing to protective labour legislation to restrict women's hours and regulate their working conditions.Footnote 51 The idea of home, family life, and motherhood was used also to exclude women from unions, while the “home-and-motherhood argument” restricted women's participation in the labour market.Footnote 52 As research has shown, in many cases male domination of labour organizations played a crucial role in women's exclusion from work in the mines and in the removal of women from workers’ organizations.Footnote 53

The role of the ILO after 1919 was vital in expanding coordinated social legislation developed mainly in response to a fear of widespread unrest.Footnote 54 The first regulations regarding women in 1919 show concern for their reproductive role: maternity leave in Convention 3; prohibition and limits on women working with lead in Convention 4; and prohibition on night work, also in Convention 4. Between 1929 and 1933, the ILO considered working hours in coal mines, and, immediately after, the employment of women and young persons. Convention 45 in 1935 saw the prohibition on the employment of women in underground work in any mine.Footnote 55 Convention 45 was the result of a “Grey Report” prepared by the ILO and of a questionnaire sent to member states. Their replies revealed that, in most countries, women's employment underground was already prohibited (in Bulgaria; several states in Canada, including British Columbia, New Brunswick, Ontario; New Zealand; Union of South Africa; Brazil; Estonia; Netherlands; Belgium; Romania), and in some of them even surface work. The scope of the regulation, which included mines, extended, too, to other analogous places, such as quarries, gravel pits, sand pits, clay pits, and to “all persons of female sex”, without any exception to the nature of substances extracted or the character of the working, “whether wholly or only partly underground”.Footnote 56 The Convention was adopted in 1935 and came into force in 1937; thirty-eight countries ratified it, meaning that the standards laid down were widely accepted and applied.Footnote 57 In article 2 of the Convention, the ILO accepted that “no female whatever her age shall be employed on underground work”.Footnote 58

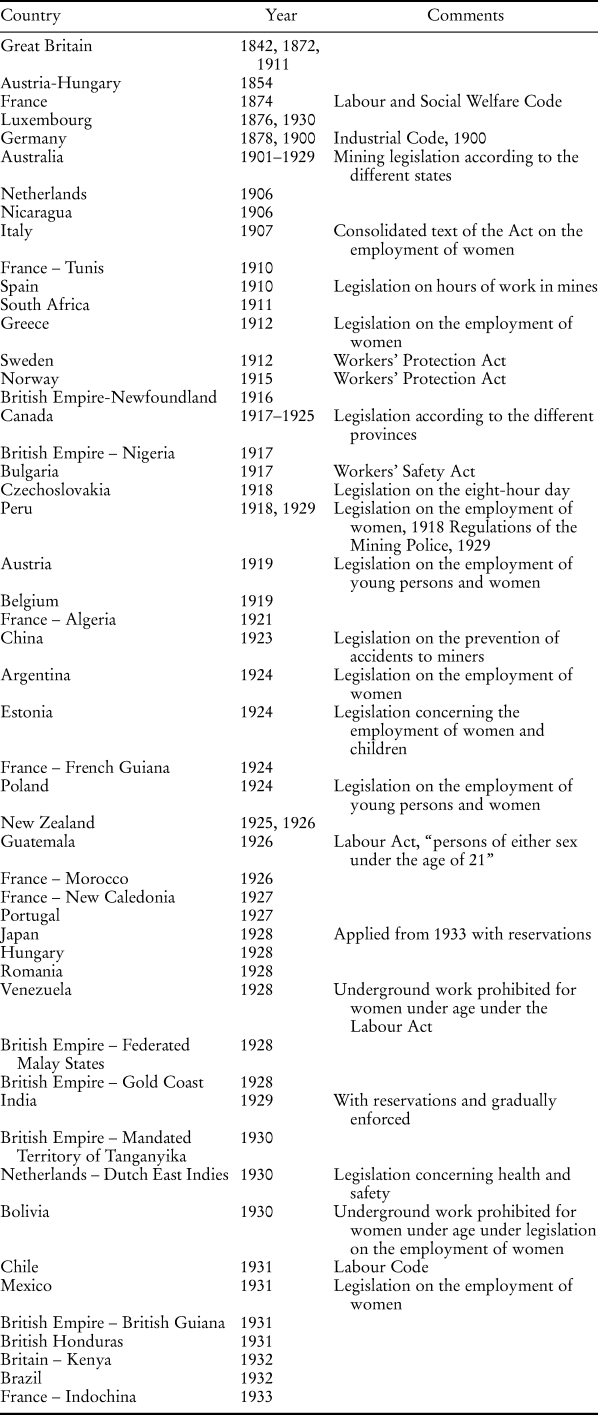

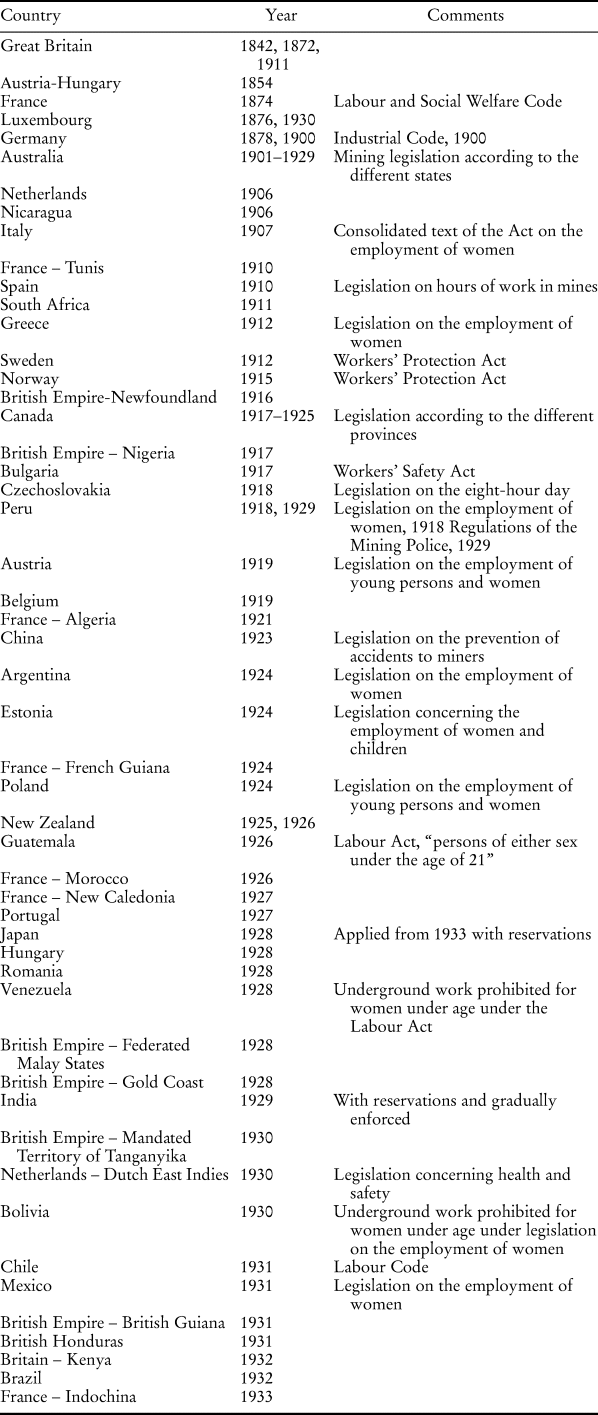

Table 2 shows the years in which women's underground work was prohibited in ILO member states, and also shows that women's work in the mines, mainly underground, had already been prohibited by many countries before Convention 45 of 1935. Some countries integrated a number of prohibitions in their mining legislation, others (like France and Chile) in more general labour legislation, or in laws concerning the employment of women (Italy, Greece, Peru, Argentina, Mexico, Bolivia), the employment of women and children together (like Austria, Estonia, Poland), number of hours worked in the mines or the eight-hour day (Spain, Czechoslovakia), or in worker protection (Sweden, Norway) and worker health and safety (Bulgaria, China, Dutch East Indies).Footnote 59

Table 2. Countries and years from which women were prohibited from working in mines (up to 1933).

Sources: ILO, Women's Work under Labour Law: A Survey of Protective Legislation (Geneva, 1932), pp. 173–177; ILO, Employment of Women on Underground Work in Mines of all Kinds, Report VI, 18th session (Geneva, 1933), pp. 9–25; BIT, Conférence internationale du Travail, Emploi des femmes aux travaux souterrains dans les mines de toutes catégories, Deuxième question à l'ordre du jour, Rapport II, dix-neuvième session (Geneva, 1935), pp. 5–11.

From 1930 to 1935, the ILO gathered information and data from member states, but although based on reports from various governments the information was not always precise. For example, in Spain the first restrictions on women working underground were not those enshrined in legislation on the number of hours worked in mines in 1910, as the ILO data suggested, but the Mining Police Regulations of 25 July 1897, which constituted the first law prohibiting women's work in underground mining in Spain.Footnote 60 In Portugal, the first restriction on women's work underground in mines was regulated by the decree of 14 April 1891 and confirmed by the decree of 16 March 1893; this is much earlier than the 1927 claimed by the ILO as the date of the earliest government regulation on women mineworkers, during the Military Dictatorship (1926–1933).Footnote 61 In Italy, the first restrictions on women's work underground did not originate with the consolidated text of the 1907 Act on the employment of women, but five years earlier, in 1902, with the law on the employment of women and children, which prohibited women from working underground. The Italian law of 1907 was necessary though because there was no real control on the application of the 1902 law, and many mining industries simply ignored it.Footnote 62 Similarly, in Greece the ban on female work underground was the result not of the law of 1912 “On the labour of women and children” but of the 1910 mining law “On mines”, which was the first legislation to prohibit the employment of women and children in jobs underground and night work in the mines.Footnote 63 It should also be noted that some of the laws mentioned in Table 2 banned not only women's work underground but also at the surface (in the Netherlands, New Zealand, Peru), or at least especially laborious work (Austria, Bulgaria, Germany, China, Great Britain).Footnote 64 In Bolivia and Guatemala, underground work was forbidden only for women under age.Footnote 65

In its reports, the ILO stated that regulations were rare in colonial territories. However, India regulated underground work by women as early as 1924, though there were important exceptions in the coal mines of Bengal, Bihar, and Orissa, and the regulation was only gradually enforced before 1939. The percentage of women in coal mines fell from twenty-nine per cent in 1929, to two per cent in 1939, and in the salt mines from forty per cent to four per cent. Nevertheless, several members of the Indian Mining Association believed that the “abolition of the employment of women underground should speed up”. In Japan, in the major coal mines, which represented eighty per cent of the coal mines, the situation was similar. The reduction planned for the mines was to be implemented quickly: from 36,759 women working in more than 198 mines in 1928, to 8,146 in 136 mines in 1931,Footnote 66 and to 6,000 by 1933. After that date, an exemption was permitted in small mines, and women might still be employed underground in mines where most of the veins were thin.Footnote 67 Some mines in the region of Kyushu requested permission to postpone evicting women because doing so would affect the livelihood of miners’ families, which were supported by women, potentially leading to “a serious situation”.Footnote 68

The role of the ILO as a supranational authority during the interwar was crucial for the promotion and implementation of global labour standards.Footnote 69 The critique of feminist historians emphasizes that ILO conventions and recommendations “have not only reflected the male breadwinner ideal that unionized men struggled to realize” since the nineteenth century, but also that these instruments “gave member states guidance on how to deploy women workers, whether for the maintenance of people or the fashioning of goods and provision of services”.Footnote 70

The Underground Work (Women) Convention (No. 45, 1935), together with the Forced Labour Convention (No. 29, 1930) and the Recruiting of Indigenous Workers Convention (No. 50, 1936) can be seen in the intersection between the engendering of international labour law and the focus on the Global South in the process of the formation of international labour standards, which the ILO pursued in order to bring sex-specific protection to the Global South. As Zimmermann argues, the Underground Work (Women) Convention was a classic measure offering special protection for women with an unusual focus on the Global South. The preparation and adoption of the Underground Work (Women) Convention in the 1930s occurred at the same time as the intensification of the conflict among women's organizations and networks over special labour protection.Footnote 71

Dhiraj Kumar Nite underlined how a number of welfare schemes relating to housing or schools were started, but with a complete absence of concern for how to ensure sufficient income for the breadwinner and the consequences of women being phased out of the underground mines. The author argues that in India forty-two per cent of the total underground workforce was evicted; this translates into a reduction in household earnings of forty per cent.Footnote 72 Recent studies have stressed how, instead of human considerations, the reforms were influenced by the transformation of the industry, including technological change.Footnote 73

Together with other measures taken by the ILO in their conventions, the spectrum of work for women was restricted, except during wartime.Footnote 74 Coal mines being associated with men and colonialism also affected societies in the twentieth century, as Carolyn Brown has shown for Enugu, where men were converted into “Boys”, transforming also social relations.Footnote 75

Mechanization and masculinization

The masculinization and hidden or veiled role of women in mines is also seen to be related to technological changes, to the underpinning of work by men in underground activities requiring strength or high levels of technology and machinery.Footnote 76 The technological innovations are thought to explain the disappearance of activities in which women once participated.Footnote 77 In collieries, for example, family work persisted as long as traditional stall-and-pillar mining prevailed. The mechanization of mining process and the replacement of stall-and pillar by long-wall mining together with the rationalization of production rendered the family system useless and women's labour underground redundant. Women's work in the mines above ground continued, as their work was considered “unskilled” and remunerated at a rate less than that of men; it was therefore cheaper. For the jobs above ground, when mechanization was introduced women's work became redundant. The gradual disappearance of women from mining work underground and in some cases above ground was a result of capitalist development and technological and organizational change, but it was also an outcome of the gender division of labour in the family and the workplace. Laurie Mercier has underlined this same directionality – that mining work by women declined when operations became more capitalized, centralized, and mechanized.Footnote 78 Angela John, on the other hand, asserted that the mechanization and replacement of women by male labour eliminated pit women in Lancashire. Her study shows that the debates about women's work raised important questions concerning domestic ideology and the tradition of opposition to their work by the official unions. However, women colliery workers were also seen as heroines when they were required during World War I, but also quickly discarded thereafter. The author underlined how the use of mechanized tumblers to tip coal, washeries, and rapid loading schemes affected women, asserting that “the age of mechanization has swept them into history”.Footnote 79

In Japan, in the first few decades of the twentieth century, mechanization in large companies led to new methods and new ways of organizing labour. Manual mining was replaced by a digging machine operated by several men; automation was also introduced to recover the coal. But women still continued to sort coal. During the recession in the 1920s they were laid off on the surface, and around 1928 women were formally banned from entering the coal mines even as haulers. Nevertheless, very soon, in the 1930s, couples were working again and women were waste-haulers in larger companies, while in medium-sized companies and small labour-intensive mines they could be more important. Only after World War II were women in large companies no longer allowed to work down the mines.Footnote 80

In almost all known cases worldwide, technological change, mechanization, rationalization of production, together with the growth in large-scale mining and the ideology of the male breadwinner model seem to have resulted in the protection/eviction of women from underground work. However, the process seems to have been much more complex that one might imagine at first glance. Considering just technology, we are confronted with a variety of changes over time and in regions all over the world in the different stages of mining exploitation: extraction; ore processing; and transport. Technological innovation includes a wide variety of possibilities, from small to more major changes, and its magnitude could have very drastic and immediate effects, but also occur very slowly and over long spans of time. This evolution was certainly not linear, and mining today is revealing because there are mines worked predominantly by hand that coexist with others that are highly automated and that incorporate very sophisticated technologies, including digital innovation. There might also be a link between them along the commodity chains complicating even more the landscape of mining. The need for rapid returns in a world with high volatility in prices of minerals and with rapid resource depletion has always limited investment. The association between mechanization and masculinization that seems to be so evident therefore deserves further study and analysis in order to understand globally how technological changes were introduced and their consequences, taking into account as well the gender ideologies and asymmetries between men and women. There are many intervening variables that need to be considered in different parts of the world and in different periods, from the eighteenth to the twentieth century.

Studies so far show that in many parts of the world the “protection” of women and the social organization of the mining industry resulted in unequal relationships between men and women being reinforced. This is why also, in the second half of the twentieth century, and particularly in its final decades, the various forms of protection were questioned in the name of equality. The ILO concluded that, since 1975, the “special measures” or protective laws acted as an obstacle to the full integration of women in economic lifeFootnote 81 and hindered the aim of equal opportunity and treatment adopted in Convention 11 in 1958 concerning discrimination in employment and occupation.

As Susan Lehrer reminds us, some feminists argued that the protective laws on women, inspired by capitalists or male workers, or both, served instead to discriminate against women. In this sense, what might appear to have been a benefit ended up as a policy against them.Footnote 82 One factor that contributed to this situation is that employers and the state considered women to be expensive when social rights were involved.Footnote 83

In the United States, feminists compelled governments to open up jobs for women through equal employment opportunities.Footnote 84 In some mining regions women demanded to be allowed to work in the mines, as happened in the famous Wyoming coal mines, where since the 1970s and 1980s one-fifth of all workers have been women. However, they were continuously confronted with having to demonstrate that they were able to deal with technology and acquire the skills necessary for their work.Footnote 85 In India, from 1999–2000, the proportion of women working in the mines rose again, from three to twelve per cent.Footnote 86 It is somehow paradoxical that the technological advances in the mining industry did not include women, while in several regions of the world women had to make a living in mines operating with low levels of capital and technology. The small mines and quarries are now the repository of the poorest workers, among whom women played and play a prominent role.Footnote 87

Women in artisanal small-scale mining and the informal economy

Today, more than thirty-five million rural people are thought to be engaged in mineral extraction in developing countries,Footnote 88 in the so-called artisanal and small-scale mining (ASM) characterized by low technology, intensive labour, low rates of production, and poor safety, health, and environmental conditions.Footnote 89 Small-scale mining was first recognized as an industry by the United Nations in 1972, while the sector experienced rapid expansion after 1990.Footnote 90 This process can be seen in the light of the shifting changes in transnational corporations, which required fewer and more flexible labour. Some data show that in 1990 there were twenty-five million workers in the mining industry worldwide; by 2000, 5.5 million jobs had been lost. The system seems now to be based mainly on subcontracted mine workers.Footnote 91 In the tin industry, for example, ninety-seven per cent of the world's production originates in developing countries, and at least forty per cent is produced by ASM.Footnote 92

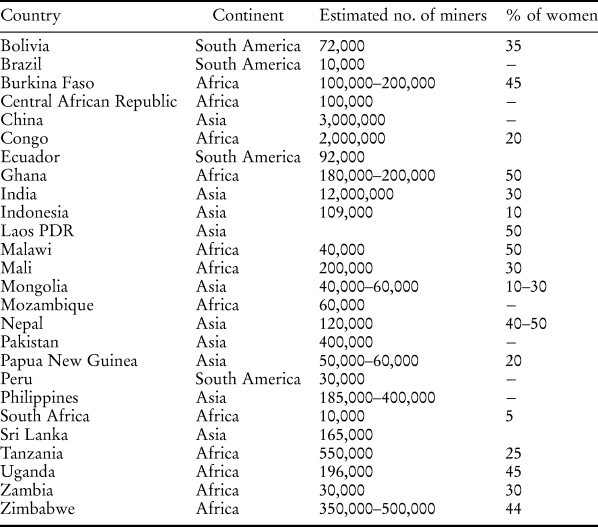

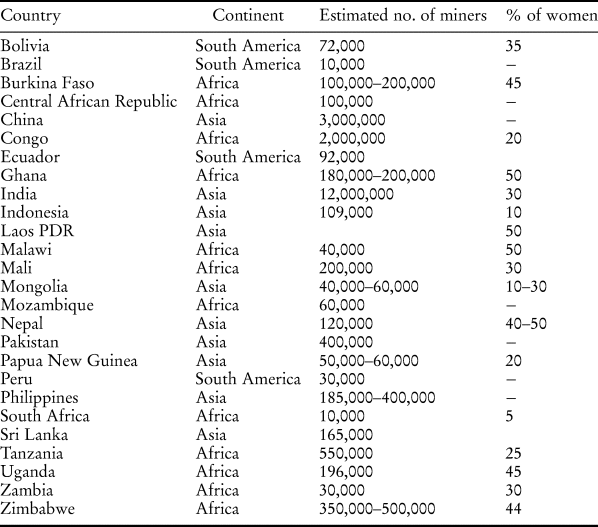

According to the ILO, in 1999 at least thirteen million people were directly employed in ASM, while 100 million depended on it for their livelihood. Other estimates suggest that in the Global South around twenty-five million people are involved in ASM across more than seventy countries. Women constitute an important part of this workforceFootnote 93 and they are particularly relevant in Africa, Asia, and Latin America, where they represent from ten to fifty per cent of the mining workforce (Table 3).

Table 3. Estimated number of miners and percentage of women, selected countries, 2005–2010.

Source: Adriana Eftimie, et al., Gender Dimensions of Artisanal and Small-Scale Mining: A Rapid Assessment Took Kid (n.p., 2012), p. 7.

Women participate in almost every stage of mineral extraction, transport, and processing of minerals. In Burkina Faso and Mali, ninety per cent of these activities are in the hands of women.Footnote 94 In other countries, such as the Democratic Republic of Congo, women are thought to account for twenty per cent of the mining workforce, and mining provides a living for between 0.8 and two million people.Footnote 95 Women here are intermediaries between mineral buyers and artisanal miners, and play a crucial role in the local commodity chain.Footnote 96

Almost eighty per cent of all gemstones are mined artisanally. Women are employed in panning, washing, and processing.Footnote 97 In the case of diamonds, before 1917, the Diamang Company in Angola worked with male and female labourers; in the last few decades of the twentieth century, women started to supply food to the company.Footnote 98 Gold exploitation is another arena for women. In Papua New Guinea, the gold industry can be dated to the late 1880s and was dominated by Europeans until 1960. Today, at least thirty per cent of the workforce there are women, engaged in manual activities such as tailings, panning, and sluicing.Footnote 99 In Ghana, gold-mining is a large-scale activity that comprises sixty-five per cent of all mining production, with 16,000 workers accounting for 66,000 jobs indirectly, while small and artisanal mining directly supports over one million individuals and creates additional employment for as many as five million. Women are omnipresent, engaged in work as ore haulers and washers, and as service providers (supplying food, clothing, water, and light mine supplies).Footnote 100 Women are also present in transporting ore and water, receiving salaries sixty per cent less than those paid to men.Footnote 101 In India, fifty-seven per cent of those involved in the small and informal gold-mining sector are women.Footnote 102

In ASM, women's labour is the result of many socio-economic and cultural barriers (including lack of education, lack of training in mining techniques, lack of access to bank credit, minimal compensation). They perform heavy manual jobs in poor working conditions, with high percentages of occupational disease and accidents.Footnote 103 Frequently, women are still working in family labour systems, as in the case of stone quarrying in eastern India; the labour contractors or owners find this system easier to manage.Footnote 104

In contrast to the “protective measures” taken by the ILO in the 1930s, today some global institutions such as the World Bank encourage the hiring of women because this is considered “good for business, good for development”.Footnote 105

This overview leads to more questions for the future than it can resolve. The emergence of large enterprises in coal, tin, iron, and other minerals, the creation of wage-workers in the mines, and technological advances necessitates a global history that could link these processes to the presence and eviction of women. The persistence, or growing importance, of women's work in small-scale and artisanal mining today, especially in the Global South as part of the globally connected mining industries, is a contemporary phenomenon that new research needs to historicize by focusing on ASM in the past. Given that the processes of proletarianization and industrialization have never been uniform throughout the world, small, artisanal, and independent mining might have been more important than we think in some regions, and the role of women might have been seriously underscored in the past, particularly in the Global South. Clearly, it is fundamentally important to analyse the role of ASM over time, and to study the long-run evolution of the gendered division of labour and the segmentation of demand and supply. We do not know, for example, whether the inclusion of women in mining today is due to a less sharp gendered division of economic activities or to a contemporary geographical expansion of extractive activities all over the world, requiring labour on a scale that did not exist before and within particular conditions. The transnational transformation of industry is now associated with flexibilized labour, subcontractors, and exploratory firms. This implies that the separation between “informal” and “formal” mining is somehow misleading because, as Samaddar has noted, throughout the history of capitalism there has always been a mix of the two. Today, contemporary capitalism uses cheap labour throughout the global supply chain, “ordaining” the informal condition of labour, particularly in the extractive industries linked to neoliberal policies.Footnote 106 In the case of Bolivia over the past decade, for example, a subsidiary enterprise of the Coeur d'Alene Mines Corporation used to buy the ores delivered by small artisanal miners without incurring the costs of extraction or the costs of labour. Here, there is a modus vivendi, with tensions between the state company, which has the legal lease of the mines and sub-leases them to the ASM (organized as cooperatives), which is characterized by informal, labour-intensive, minimally mechanized, and low-technology mining operations.Footnote 107 There are connections and even a vertical integration between the formal sector and the small-scale and artisanal mining of the informal sector.

Although we have so far stressed the role of women as mine workers because this has generally been less emphasized in the literature, women were also in charge of their households, and much more, especially after being put aside as a consequence of legislation after the nineteenth century.

PRODUCTION AND REPRODUCTION IN THE MINES

The activity of mining as centred on the work of men ignored the important domestic work carried out by women and children. The association of work with value in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries meant that only those “activities that were performed for pay or that generated income” were regarded as value-producing. Work was progressively perceived as a commodity. Labour was defined as such only if it had market value, that is, if it could be measured in monetary terms. Activities necessary to individual and collective survival and well-being which had only a socially useful value were ignored and regarded as counter-productive work, because they did not produce goods destined for the market, and, being unpaid, were not considered an “occupation” or “employment”.Footnote 108

As activities of care and domestic tasks were frequently performed at home and mainly by women, this change towards “unproductive” labour was not gender neutral. The perception of tasks and skills (such as childcare, cooking, keeping the household, nursing) as being “natural” for women originated a new gendered division of labour in the workplace and at home: men were supposed to be the principal wage earners for their families; women were supposed to participate in secondary, auxiliary roles as wives, mothers, and housewives.Footnote 109

Over the past forty years, feminist critique has repeatedly reconsidered the Marxist dichotomy between “productive” and “reproductive” labour, expanding the concept of work to include non-monetized subsistence and family activities illustrating the diversity of ways in which “reproduction is production over time and space”, challenging the “naturalization” of homework.Footnote 110 Feminist historians have also recognized the gendered division of labour within the forms of subsistence production and highlighted “the power relations within family and home”, while they have also investigated the “structural impact” of non-paid labour by women in families and households.Footnote 111 Moreover, research has often questioned the significance of the sole male breadwinner family, focusing on the workforce that had been neglected, specifically women and children. It is noteworthy that the male breadwinner family has its origins in Western family ideology.Footnote 112

As has been shown by research all over the globe, the household or family budget comprises various incomes: monetary and non-monetary goods and services from different social relations of paid and unpaid work. It has also highlighted the central role of unpaid work in the maintenance of the family and the household, while recent research has also explored the diversity of adaptive family economies.Footnote 113

In mining communities, women's work was essential to the well-being of miners’ families, as women were responsible for housekeeping and childcare. Recent research has explored new sources, such as oral testimonies and autobiographies, to trace women's everyday life in mining communities and to depict the unpaid work of women in the reproductive sphere of the mining families. As Valerie G. Hall has noted for coal-mining communities in England,

the nature of work in the mine and the culture of the miners meant a heavy domestic role for wives […] Work in the pit was both dangerous and arduous and was conducted in terrible conditions […] The routine of the household revolved around the routine of the pits and the needs of the miners,Footnote 114

as women were obliged to prepare baths and meals and wash the work clothes of the men according to the shifts of the male miners in every family.Footnote 115 Women's household and cooking skills were more than crucial for the existence of the family in times of crisis, unemployment, or underemployment.Footnote 116 Moreover, in many mining communities women in England, Belgium, France, and the Mediterranean region were responsible for creating a clean and comfortable domestic environment for the miners, and for ensuring a modest lifestyle.Footnote 117

Besides, the hazards of mining and their consequences were part of the mining families’ daily lives: the threats of death and injury, the black lung, the threats of unemployment and illness. Miners’ wives had to manage their daily lives in the face of such threats, while shift work caused numerous problems in the daily life of the family. Women's attitudes to this harsh existence depended on the cultural tradition of each mining community and on the resilience, flexibility, and endurance of the people themselves.Footnote 118 As Carol Giesen put it, “the [miners] men faced the dangers every day but it was the women who ‘carried the mine in them’”.Footnote 119 Through good homemaking and childcare, by bearing the bulk of the family's responsibilities, the miners’ wives supported their husbands, and usually felt a certain pride in doing so.Footnote 120

To transform migrant rural labourers into a permanent and trained labour force, mining enterprises used to offer various facilities for workers and their families (accommodation, schools, healthcare, etc.) and implemented gendered social welfare policies. This seems to have been the case in a number of mines, including copper mines in Chile, Zambia, and Congo,Footnote 121 and in lead and iron mines in Greece during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.Footnote 122 In Europe and North America, the miner's family was at the centre of various paternalistic policies designed to control and ensure the stability of labour. According to the gendered ideology of domesticity, usually originating in Victorian middle-class values, women were responsible for housekeeping, care of the children, and the well-being of the family, but this gendered ideology interconnected with the male miner's productivity in the workplace.Footnote 123 In Sweden, many mine owners encouraged miners to marry and bring their wives and families with them, as they believed that married men could be more productive and family life created a harmonious milieu of social order and stability.Footnote 124

The important reproductive tasks of miners’ wives and daughters in the mining family are closely related to the mechanization and rationalization of mining work, now performed exclusively by men, as their strenuous efforts, in day and night shifts, were possible only with a caring homemaker. There seems to have been a correlation between the mechanization and rationalization of the mining process with the removal of women because of the replacement of family teams, the intensification of mine work owing to technological change, and the relegation of women to housewives and homemakers.Footnote 125

Although in mining communities, women and girls had limited options for paid work outside the home,Footnote 126 they managed the family budget or contributed to the family income through many informal activities. Invisible women's labour in the mines and in mining areas tended to take the form of informal paid or unpaid activities (such as taking in lodgers, taking in laundry, baking bread, sewing, being engaged in small-scale subsistence agriculture).Footnote 127 Women's contribution to family income was extremely important in times of crisis, illness, or unemployment. In the case of the Sardinian mines in 1940s and 1950s, women could contribute to the family's income through their waged work in the mines and by helping to buy the land on which to build the family house.Footnote 128 In South Africa's coal-mining areas, women were responsible for agricultural production and diverse forms of reproduction (from preparing food to selling sex).Footnote 129 The prostitution that developed in mining regions and company towns in diverse national and colonial contexts from the mid-nineteenth century seems a permanent and complex phenomenon of capitalist development.Footnote 130

Women created diverse networks of sociability and solidarity in the mining communities. Valerie Gordon Hall has challenged the strict division of labour among male miners and housewives even in “homogenous” patriarchal coal-mining communities by pointing to the variability of female identities among “housewives” and “political women” and activists. As she argues, in the period 1900-1939 women in Northumberland adopted new ideologies, such as feminism and socialism, while forging new political identities.Footnote 131 Before World War II, in Yubari, a coal-mining town in Japan, women created networks of sociability, with gatherings for tea, discussions, and sewing lessons. Because of the cramped space in the houses provided by the mining company, these women had to leave their homes and go somewhere “to kill time”, to allow their husbands to sleep quietly after a night shift in the mines. Gradually, these women's gatherings and informal support system became a formal system of mutual aid when the mine workers’ unionized. At the end of World War II, women supported union organization among miners.Footnote 132

Marcel van der Linden has suggested that, since there were several household strategies available to households to improve their living conditions, it might be important to analyse the different forms of activism among women and households.Footnote 133 In mining communities, limited economic alternatives and the gendered division of labour often led women to regard their interests as closely tied to those of their husbands and fathers. Jaclyn Gier and Laurie Mercier have noted that abundant historical examples from mining communities worldwide “reveal how women exaggerated gender claims to secure solidarity for what they viewed as family and community, not just union, efforts”.Footnote 134 We can trace many different traditions of protest for women in mining communities around the world, depending on the particular historical context. Women were often committed to activism and participated actively in industrial disputes and miners’ strikes (in the great coalminers’ strike in Anzin, France, in 1884, or the Southern Colorado coal strike in 1913–1914 for instance) and in some cases in the political struggles of miners.Footnote 135 One example was the case of “Women against Pit Closures” during the 1984–1985 miners’ strike in Britain,Footnote 136 when the promotion of gay and lesbian concerns within the labour movement was combined with the construction of new solidarity networks.Footnote 137 At least in one case, during the long Empire Zinc strike in New Mexico in 1950–1952, women came to rebel not only against the mining company but also against their husbands.Footnote 138

PRESENTATION

Women were mine workers, but they were also responsible for their households, contributing as well to the income of their families and to their struggles. In this Special Theme, we present three different case studies (from Bolivia in the sixteenth to the eighteenth centuries, Spain, and Greece between 1860 and 1940) that illuminate the variety of women's experience in the mines and the shaping of gender relations. The first study analyses silver production in Potosí during Spanish rule, when women did not work underground but did play a crucial role in surface activities. The second scrutinizes women's work in the mines in Spain much later, while the third focuses much more on how gender relations shaped the whole industry.

In her article “Women in the Silver Mines of Potosí: Rethinking the History of ‘Informality’ and ‘Precarity’ (Sixteenth to Eighteenth Centuries)”, Rossana Barragán Romano focuses on the direct involvement of women in silver production, refining, and trade. She reconsiders and historicizes what it is now called “informal” labour and the artisanal and small-scale mining (ASM) associated with precarity and re-reads the history of mining in Potosí. The article argues that formal and informal employment developed at the same time because they exist in relation to one another. Barragán reconstructs how indigenous women played a crucial role in the early period of Potosí, between 1545 and 1575, underlining the complex process of work and division of labour that emerged later on. One of her main contributions to the analysis of silver mines is to show that a circuit based on small and independent workers developed in the second half of the eighteenth century and that women were actively involved in refining ore in rudimentary mills or trapiches, selling the silver obtained to the Bank of San Carlos.

In their article on “Female Workers in the Spanish Mines, 1860–1940”, Miguel Á. Pérez de Perceval Verde, Ángel Pascual Martínez Soto, and José Joaquín García Gómez study the direct employment of women in the mines in the golden age of this industry in Spain. The authors show clearly that the mining regulations at the end of the nineteenth century prohibiting the employment of women in underground mining in Spain legalized the prevailing situation. Women were therefore concentrated mainly in surface work, with important differences: they accounted for around five per cent of the total surface workforce, although in some exceptional cases, as in the manganese mines, women comprised thirty-three to fifty per cent in the Huelva region between 1902 and 1934 and twenty per cent in the Asturias mines, dropping to ten per cent in 1931–1934. This study shows also the enormous gender wage gap (they earned just forty per cent of the average wage of men who worked on the surface), which widened after 1920. The removal of women from the mines was considered an improvement for the working class, and the trade unions supported this policy. Although women participated actively in the most important mining conflicts, the reports did not mention any female “voice”.

In her article “Family, Gender, and Labour in the Greek Mines, 1860–1940”, Leda Papastefanaki argues that there are gender relations in the division of labour in the workplace, as well as in the family in mining communities. Her essay analyses the intersection between gender, family, and labour in some exemplary mining areas, such as Lavrion, Seriphos, and Euboea. She argues that the migration trajectories of the miners have gendered dimensions at both ends – in the place of origin and in the mining areas – as miners’ migration was supported by the family in many ways. The control of migrant labour in mining areas interconnected with paternalistic policies of the companies that aimed to stabilize the workforce and create an attractive family environment to encourage and attract them to stay. Papastefanaki focuses on the gendered division of labour in Greek mines, which underlay women's inferior status in the mining process. An important contribution of this study is to underline the multiple meanings of the concept of “skilled labour” determined by the gendered social relations of power: the “risk-taking” character of male miners in comparison with the work performed by women and children on the surface, which was considered “unskilled” and “auxiliary”.