Abstract

To solve the direct problem of central forces when the trajectory is an ellipse and the force is directed to its centre, Newton made use of the famous Lemma 12 (Principia, I, sect. II) that was later recognized equivalent to proposition 31 of book VII of Apollonius’s Conics. In this paper, in which we look for Newton’s possible sources for Lemma 12, we compare Apollonius’s original proof, as edited by Borelli, with those of other authors, including that given by Newton himself. Moreover, after having retraced its editorial history, we evaluate the dissemination of Borelli's edition of books V-VII of Apollonius’s Conics before the printing of the Principia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

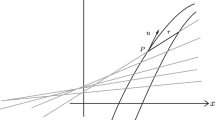

“Parallelogramma omnia circa datam Ellipsin descripta esse inter se aequalia. Idem intellige de Parallogrammis in Hyperbola circum diametros ejus decriptis”, (Newton 1687, 47). In the second edition of the Principia (1713), the statement was corrected in the form: “Parallelogramma omnia, circa datae Ellipseos vel Hyperbolae diametros quasvis conjugate descripta, esse inter se aequalia” (Newton 1687). The English translation is from (Newton 1729).

The parallelograms have to be understood circumscribed to the conic section with touching points at the extremities of pairs of conjugate diameters. Although this is not clearly expressed in Newton’s enunciation, in the subsequent proposition, he applied the lemma in this correct form.

For the spelling of Arabic and Persian names, we refer to (Toomer 1990).

The letter L in our notation indicates the Laurenziana Library of Florence where the manuscript is kept, MS. Orientale 296.

The letter B in our notation indicates the Bodleian Library of Oxford where the manuscript is kept, MS. Marsh 667.

For the uncertainty about Clavius’s German surnane see (Lattis 1994).

In a catalogue found by Guglielmo Libri in the Bibliothéque Royale of Paris, under the title “Libri imprimendi in lingua arabica Romae in typographia Ducis Hetruriae cui praeest Jo. Baptista Raymundus” and belonging to Nicolas-Claude Fabri de Peiresc, there are the entries “Apollonii Pergei libri 8, de conis” and “Ejusdem liber de sectionibus”, where, among those regarding Archimedes, we found “liber lemmatum, ex Thebit traditione”, perhaps Archimedes’s opera published by Borelli (1661) which was enclosed in the same manuscript of the seven books of Apollonius’s Conics (Libri 1838, 236–237). The same catalogue can be found, with small differences, in (Labbe 1657, 250–258). In this work there is another list of manuscripts under the title “Libri Chaldaei et arabici in poter del Reverendissimo Patriarca di Antiochia in Roma”, which lists “In Mathematica Euclide, Apollonio lib.7 Theordosio: Additione sopra Euclide di Nesir il dinel Iusi” (Ibidem, 258).

The catalogue is preserved at the Bodleian Library in Oxford, MS. Add. C 296, ff. 172v–173v.

Two copies, beside the original manuscript, are preserved at the Biblioteca Laurenzia in Florence, MS. Orientale 275 and MS. Orientale 270.

The knowledge of the presence in Rome of the Arabic version of Apollonius’s Conics is recorded in Clavius’ correspondence. See (Clavius 1992, letters 65, 256).

See the letter that Borelli addressed to Prince Leopoldo, on 12 April 1656, in (Giovannozzi 1916, 5).

See the letter of Borelli to Viviani published in (Tenca 1956, 116).

First published in Italian by Giovannozzi (1916, 7).

In the preface, Viviani tell us the long story, which began when he was twenty-two, and his words show how much he cared about this work.

Pieter van Gool was a Carmelite, he had travelled in Syria and Lebanon and in those years he was at the Convent of San Pancrazio in Rome, see (Thomas 1939, 828–829).

See the letter of Borelli to Dati, the 31 January 1665, published in (Guerrini 1999, 513).

The letter is published in (Guerrini 1999, 514).

For more information on the method, see (Brigaglia and Nastasi 1984, 14–15).

“In ellypsi, et sectionibus conjugatis parallelogrammum sub axibus contentum aequale est parallelogrammuo à quibuscunque duabus conjugatis diametric comprehenso, si eorum anguli aequales fuerint angulis ad centrum contentis à conjugatis diametris”, (Apollonius 1661, 370).

In a note on p. 372, Borelli pointed out that since in the Arabic manuscript the statement concerning the ellipse was numbered “9”, he thought it right to insert it as prop. XXXII, after prop. XXXI, the one concerning the conjugate hyperbolas.

According to Borelli’s notation, Par(MK) denotes the parallelogram KLMN (K and M are two opposite vertices).

We stress that in the text it is erroneously indicated as prop. 39, I.

In the text proposition 24 of book II is quoted, but it is a mistake as the latter regards the parabola.

In this formula and in the following, “T (ABC)” denotes the triangle of vertices A, B, C and two equal triangles means that they are equivalent.

To explain this implication Borelli made a note adding:

$$ T\left( {EOF} \right){:}T\left( {EHP} \right) = OR{:}RE $$(I)Now, the triangle EFK is medium proportional between the two similar triangles EOF, and EHP, in fact, the two triangles EOF, EFK, having equal height, are between them as their respective basis, that is \( T\left( {EOF} \right){:}T\left( {EFK} \right) = OF{:}FK = OF{:}EH \). The same is EHP and EHK, which also have the same height and then they are between them as their basis, that is \( T\left( {EHP} \right){:}T\left( {EKH} \right) = HP{:}HK = HP{:}FE. \) On the other hand T(EFK) = T(EKH), thus we have

$$ T\left( {EOF} \right){:}T\left( {EFK} \right) = T\left( {EFK} \right){:}T\left( {EHP} \right) $$(II)Since \( SR^{2} = OR \times RE, \) from (I) and (II) it follows that

$$ T\left( {EOF} \right){:}T\left( {EFK} \right) = SR{:}RE, $$Therefore, we get

$$ 2T\left( {EOF} \right){:}2T\left( {EFK} \right) = SR{:}RE, $$$$ 2T\left( {EOF} \right){:}Par\left( {EK} \right) = SR{:}RE, $$In translating from the Arabic the lettering of the diagrams, Borelli adopted the Latin alphabet, while Halley used the Greek, as was natural since he was editing the first four books in the original language.

“Si ducantur diametri quaevis conjugatae in Ellipsi, vel inter sectiones oppositas conjugatas; erit parallelogrammum contentum sub his diametris aequale rectangulo sub ipsis Axibus facto: modo anguli ejus aequales sint angulis ad centrum sectionis à diametris conjugatis comprehensis”, (Apollonius 1710, 115); we have adopted the English translation by Heath (Apollonius 1896).

Barrow had developed a symbolic formalism in his Optical lectures (1667) and Geometrical lectures (1670). It consisted in the use of special symbols by which statements and proofs could be make easier to read.

When Golius died in 1667, his valuable collection of manuscripts remained in the hands of his heirs, but the copies he had made of the Arabic version of the Conics were available in the Leiden University library.

That volume came from Barrow’s library, and years before Newton had studied on it.

We stress that Newton’s proof cannot be extended to the case of the hyperbola.

“In quocunque angulo, et quibuslibet intervallis, juxta definitiones hoc capite propositas, curvâ descriptâ, hoc ipsi proprium erit, ut quadratum cujuslibet secanti aequidistantis, à quolibet directricis puncto ad curvam applicatae, eandem rationem habeat ad rectangulum sub partibus directricis per applicatam factis, quam quadratum secantis ad quadratum directricis”, (De Witt 1661, 205).

“Atque ita liquet, praedictam curvam eam ipsam esse, quae Veteribus Ellipsis dicta fuit, directricem verò ac secantesm eas ipsa, quas conjugatas diametros appellabimus, aut, si angolus rectus fuerit, conjugatos axes vocârunt”, (De Witt 1661, 208). In fact, by taking the directrix and the secant as coordinate axes, and putting x, y the coordinate of L, AE = a and AH = b, from the relation above we have y2:(a + x) (a − x) = (2b)2:(2a)2, which leads to the equation x2/a2 + y2/b2 = 1. If we denote α the angle CAH, and we consider orthogonal coordinates X, Y with origin at A and the directrix as X-axis, the equation of the conic is a−2(X − Ycotα)2 + (b·sinα)−2Y2 − 1 = 0.

“In Ellipsi circa quoscunque axes descriptâ, ducta quaelibet diameter transversa est, habet que secundam sibi conjugatam”, (De Witt 1661, 213).

A reproduction of Newton’s original note is also given in (Galuzzi 1990, 415).

Newton was aware of other works by La Hire. Certainly he knew La Hire’s Nouvelle méthode, etc. (1673), see for instance (Guicciardini 2009, 84, note 15), and the Nouveaux éléments des sections coniques (1679), a copy of which he had in his library (Harrison 1978). According to Whiteside, see (Whiteside 1970, VI, 271), from the Planiconiques appended to (La Hire 1673), Newton might have found inspiration for his studies on transformation of figures.

MS 210 of the Royal Society, see (Guicciardini 1999, 179–183).

“Rectangulum sub dimidjis axibus aequale est parallelogrammo sub semidiametris coniugatis” (Saint Vincent 1647, 281).

“Si fuerint binae hyperbolarum coniugationes A, B, C, D: ponantur autem per E centrum duae quoque diametrorum coniugationes per quarum vertices contingents actae constituant duo quadrilatera FGHA, OPQR. Dico illa esse aequalia inter se”, (Saint Vincent 1647, 560).

“Sequitur secondo parallelogramma sub totis diametris coniugatis, inter se esse aequalia cum sint quadrupla eorum quae hac propositione ostensa sunt aequalia”, (Saint Vincent 1647, 281).

“Expositio brevis, singularum propositionum Conicorum Apollonii Pergaei, cum ipsarum demonstrantionibus ex nostra methodo deductis”, (La Hire 1685, 220).

La Hire implicitly referred to Viviani, see below, but when specifying “the last three books” he included necessarily Borelli.

He meant the fifth of Apollonius in Borelli’s edition.

“In sectionibus conjugatis NA, DL, BM, KE si circumscribatur parallelogrammum FGHI à rectis parallelis duabus diametris inter se conjugatis ED, BA, et per ipsorum terminus ductis, et simili methodo circumscribatur aliud parallelogrammum OPQR à rectis ductis per terminos diametrorum conjugatarum, et ipsis parallelis: Dico parallelogramma FGHI, OPQR esse inter se aequalia”, (La Hire 1685, 85).

“Si Ellipsi circumscribatur parallelogrammum MNPK cujus latera sint duabus diametris inter se conjugatis AB, DO aequidistantia: similiter aliud parallelogrammum ELGF circumscribatur, cujus latera sint duabus aliis HS, IT diametris inter se conjugatis parallela”, (La Hire 1685, 99).

“In sectionibus conjugatis et Ellipsi parallelogrammum sub axibus aequale est parallelogrammo sub duabus quibuscumque diametris inter se conjugatis, in angulis ipsarum diametrorum conjugatarum”, (La Hire 1685, 243).

Page 41 of the manuscript held at the Cambridge University Library, see also (Rigaud 1838, Appendix, 2).

Available on line in the website of the Utrecht University Library.

“Parallelogramma omnia, circa datae Ellipseos vel hyperbola diametros quasvis conjugatas descripta, esse inter se aequalia”, (Newton 1713, 45).

References

Agostini, A. 1930. Notizie sul ricupero dei libri V, VI, VII delle “Coniche” di Apollonio. Periodico di Matematiche 11 (s. IV): 293–300.

Apollonius. 1566. Apollonii Pergaei Conicorum libri quattuor una cum Pappi Alexandrini Lemmatibus et commentariis Eutocii Ascalonitae. Sereni Antinsensis Philosophi libri duo nunc primum editi quae omnia nuper Federicus Commandinus. Bononiae, ex officina Alexandri Benatii.

Apollonius. 1661. Apollonii Pergaei Conicorum libri V, VI, VII…. paraphraste Abalphato Asphahanensi nunc primum editi. Additus in calce Archimedis assumptorum liber, ex codicibus Arabicis mss. Serenissimi Magni Ducis Etruriae Abrahamus Ecchellensi Maronita… Latinos reddidit; Io. Alfonsus Borellus … curam in geometricis versioni contulit, & notas uberiores in universum opus adiecit…. Florentiae, Ex Typographia Iosephi Cocchini.

Apollonius. 1669. Apollonii Pergaei Conicorum libri V. VI. & VII in Graecia deperditi, jam vero ex Arabico Manuscripto ante quadringentos annos elaborato opera subitanea Latinitate donata à Christiano Ravio. Kilonij, Sumptibus Salomonis Reyheri.

Apollonius. 1710. Apollonii Pergaei Conicorum libri octo et Sereni Antissensis de Sectione Cylindri et Coni libri duo. Oxoniae, E Theatro Sheldoniano.

Baldini, U. 2003. The Academy of Mathematics of the Collegio Romano from 1553 to 1612. In Jesuite Science and the Republic of Letters, ed. Feingold M., 47–98. Boston: MIT Press.

Barrow, I. 1675. Archimedis Opera: Apollonii Pergaei Conicorum linri IIII. Theodosii Sphaerica: Methodo Nova Illustrata & Succincte Demonstrata per Is. Barrow. Londini, excudebat Guil. Godbid.

Borelli, G.A. 1679. Elementa Conica Apollonii Pargaei et Archimedis Opera nova et breviori methodo demonstrata. Romae apud Mascardum.

Bortolotti, E. 1924. Quando come e da chi ci vennero recuperati i sette libri delle “Coniche di Apollonio”. Periodico di Matematiche 4 (s. IV): 118–130.

Brigaglia, A., and P. Nastasi. 1984. Le soluzioni di Girolamo Saccheri e Giovanni Ceva al “Geometram quaero” di Ruggero Ventimiglia: Geometria proiettiva italiana nel tardo Seicento. Archives for History of Exact Sciences 30 (1): 7–44.

Clavius, C. 1992. In Corrispondenza, ed. U. Baldini and D. Napolitani. Pisa: Department of Mathematics, Università di Pisa.

De Witt, J. 1661. Elementa Curvarum Linearum edita Operâ Francisci à Schooten in Academia Lugduno-Batava Matheseos Professoris. In Renati Des-Cartes Geometriae pars secunda, 153–340. Amstelaedami, apud Ludovicum & Danielem Elzevirios.

Descartes, R. 1659–1661. Geometria, à Renato Des Cartes Anno 1637 Gallicè edita; postea autem Unà cum Notis Florimondi De Beune In Curia Blesensi Consiliarii Regii, gallicè conscriptis in Latinam linguam versa, & Commentariis illustrata, Operâ atque studio Francisci à Schooten in Acad. Lugd. Batava Matheseos Professoris. Amstelaedami, apud Ludovicum & Danielem Elzevirios.

Feingold, M. 1990. Isaac Barrow: Divine, Scholar, Mathematician. In Before Newton. The Life and Times of Isaac Barrow, ed. Mordechai Feingold. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Galuzzi, M. 1990. I marginalia di Newton alla seconda edizione latina della Geometria di descartes e i problemi ad essi collegati. In Descartes: il Metodo e i Saggi, Atti del Convegno per il 350° anniversario della pubblicazione del Discours de la Méthode e degli Essais, a cura di Belgioioso, G., Cimino, G., Costabel, P., Papuli, G. Istituto della Enciclopedia Italiana, 387–418.

Gassendi, P. 1630. Catalogus rarorum librorum quos ex Oriente nuper advexit, & in publica Bibliotheca inclytae Leydensis Academiae deposuit,.. Iacobus Golius. Paris: excudebat Antonius Vitray.

Giovannozzi, G. 1916. La versione borelliana di Apollonio. Memorie della Pontificia Accademia Romana dei Nuovi Lincei 2 (s. II): 1–32.

Grandi, G. 1712. Risposta apologetica del P. maestro D. Guido Grandi camaldolese… alle opposizioni fattegli dal Sig. dottore A. M. nella sua dotta lettera diretta all’eccellenza del sig. B.T. Lucca, per Pellegrino Frediani.

Gregory, David. 1702. Astronomiae physicae & geometricae elementa. Oxoniae, E Theatro Sheldoniano.

Guerrini, L. 1999. Matematica ed erudizione. Giovanni Alfonso Borelli e l’edizione fiorentina dei libri V, VI, VII delle Coniche di Apollonio di Perga, Nuncius 14 (2): 505–568.

Guicciardini, N. 1999. Reading the Principia. The Debate on Newton’s Mathematical Methods for Natural Philosophy from 1687 to 1736. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Guicciardini, N. 2009. Isaac Newton on Mathematical Certainty, MIT Press Edition.

Harrison, J. 1978. The Library of Isaac Newton. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press.

Heath, T.L. 1896. Apollonius of Perga Treatise on Conic Sections edited in modern notation with introductions including an essay on the earlier history of the subject. Cambridge: University Press.

Labbe, Ph. 1657. Nova Bibliotheca Mss. Librorum. Pariis, apud Io. Henault.

La Hire, Ph. 1673. Nouvelle méthode en géometrie pour les sections des superficies coniques, et cylindriques qui ont pour bases des cercles, ou des Paraboles, des Elipses, & des Hyperboles. Paris: chez l’Autheur et Thomas Moette.

La Hire, Ph. 1685. Sectiones Conicae in novem libros distribute. Parisiis, apud Stephanum Michallet.

Lattis, J.M. 1994. Between Copernicus and Galileo. Chicago: The University Chicago Press.

Libri, G. 1838. Histoire des Sciences Mathématiques en Italy, tome I. Paris: Renouard.

Maccagni, C., and G. Derenzini. 1985. Libri Apollonii qui… desiderantur. In Scienza e filosofia. Saggi in onore di Ludovico Geymonat, ed. C. Mangione, 678–696. Garzanti: Milano.

Mersenne, M. 1644. Universae geometriae mixtaeque mathematicae synopsis et bini refractionum demonstratarum tractatus. Parisiis, apud Antonium Bertier.

Newton, I. 1687. Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica. Londini, Jussu Societatis Regiae ac Typis Iosephi Streater.

Newton, I. 1713. Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica editio secunda, Cantabrigiae.

Newton, I. 1729. The Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy. London: Printed by Benjamin Motte.

Newton, I. 1961. The Correspondence of Isaac Newton, ed. H.W. Turnbull, 5 vols.

Newton, I., and D.T. Whiteside. 1967–1981. The Mathematical Papers of Isaac Newton, vol. 8. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Pappus. 1588. Mathematicae Collectiones a Federico Commandino Urbinate in latinum conversae et commentariis illustratae. Pisauri, apud Hieronymum Concordiam.

Rigaud, S. 1838. Historical Essay on the First Publication of Sir Isaac Newton’s Principia. Oxford: At the University Press.

Rowlands, P. 2017. Newton and the Great World System. Singapore: World Scientific.

Saint Vincent, G. 1647. Opus geometricum quadraturae circuli et sectionum coni decem libris comprehensum. Antverpiae, apud Ioannem et Iacobum Meursios.

Targioni Tozzetti, G. 1780. Atti e Memorie inedite dell’Accademia del Cimento e notizie aneddote dei progressi delle scienze in Toscana. tomo I, Firenze, G. Tofani.

Taton, R. 1953. La première œuvre géométrique de Philippe de La Hire. Revue d’Histoire des Sciences et de leurs applications 6 (2): 93–111.

Tenca, L. 1956. Le relazioni fra Giovanni Alfonso Borelli e Vincenzo Viviani. Rendiconti dell’Istituto Lombardo di Scienze e Lettere, classe di scienze matematiche e naturali 90: 107–121.

Thomas, P. 1939. A chronicle of the Carmelites in Persia. London.

Toomer, G.J. 1990. Introduction in Apollonius Conics Books V to VII. The Arabic Translation of the Lost Greek Original in the Version of the Banū Musā, vol I: Introduction, Text and Translation. New York: Springer.

Toomer, G.J. 1996. Eastern Wisdom and Learning: The Study of Arabic in the Seventeenth-Century England. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Ver Eecke, P. 1923. Le coniques d’Apollonius de Perge, Oeuvres traduites pour la première fois du grec en français avec une introduction et des notes. Paris: A. Blanchard.

Viviani, V. 1659. De maximis, et minimis geometrica divinatio in quintum conicorum Apollonii Pergaei adhuc desideratum. Florentiae, apud Ioseph Cocchini.

Whiteside, D.T. 1970. The Mathematical Principles underlying Newton’s Principia Mathematica. Journal for the History of Astronomy 1: 116–138.

Whiston, W. 1749. Memoirs of the Life and Writings of Mr. William Whiston. London, printed by the Author.

Acknowledgements

We like to express our warmest thanks to Niccolò Guicciardini for having provided us with copy of some documents concerning Newton.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Communicated by Niccolò Guicciardini.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Del Centina, A., Fiocca, A. Borelli’s edition of books V–VII of Apollonius’s Conics, and Lemma 12 in Newton’s Principia. Arch. Hist. Exact Sci. 74, 255–279 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00407-019-00244-w

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00407-019-00244-w