Abstract

A large literature addresses the processes, circumstances and motivations that have given rise to archives. These questions are increasingly being asked of digital archives, too. Here, we examine the complex interplay of institutional, intellectual, economic, technical, practical and social factors that have shaped decisions about the inclusion and exclusion of digitised newspapers in and from online archives. We do so by undertaking and analysing a series of semi-structured interviews conducted with public and private providers of major newspaper digitisation programmes. Our findings contribute to emerging understandings of factors that are rarely foregrounded or highlighted, yet fundamentally shape the depth and scope of digital cultural heritage archives and thus the questions that can be asked of them, now and in the future. Moreover, we draw attention to providers’ emphasis on meeting the needs of their end-users and how this is shaping the form and function of digital archives. The end user is not often emphasised in the wider literature on archival studies and we thus draw attention to the potential merit of this vector in future studies of digital archives.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In this article we examine the selection choices that have underpinned and shaped an exemplary sample of public, private and public-private, large-scale newspaper digitisation projects. We refer to the digital collections that result from these projects as digital archives, a term with wide purchase and many definitions (e.g. Price 2009; Moss 2017). For the purposes of this article, we use the term ‘digital archive’ to refer to a systematic or intentional collection of digitised materials, specifically retro-digitised surrogates of hard copy, historical newspapers. We moreover understand that a digital archive is comprised of binary data, that can be “analys[ed] by a range of sophisticated tools … [and] are capable of being interpreted in a range of different ways” (Moss et al. 2018). This article explores the following research questions: Which processes, circumstances and motivations have influenced decisions about the inclusion and exclusion of historic newspapers in digital archives? How have providers identified the needs of their end-users, and how are they using such understandings to shape the form, affordance and function of their digital archives? How do providers reflect on the implications of their selection choices and the digital archives they have created?

To answer these questions, we mine a series of semi-structured interviews that we conducted with librarians, archivists and digital content managers in public institutions and commercial companies based in Australia, the Netherlands, UK and USA. Semi-structured interviewing is appropriate for this study because it can support the recovery and collection of rich and situated information about respective actors’ digitisation activities that is not otherwise in the public domain. We bring our inductive, thematic analysis of interviews into conversation with the wider academic and professional literature on historic newspaper digitisation, leading to a highly detailed snapshot of current digital newspaper practices.

Our findings include reflections on the complex interplay of institutional, intellectual, economic, technical, practical and social factors that have shaped decisions about the inclusion and exclusion of historical newspapers in and from digital archives. We draw attention to the largely undocumented sway of the user of digital archives, and of how the tracking of their behaviour is shaping the bundling and re-bundling of digital archives (hence we refer to them as the ‘algorithmic user’). Drawing on these findings, we furthermore set out recommendations for digitisers of cultural heritage materials about the documentation that should be bundled with their digital archives.

Our work speaks to wider debates within the Digital Humanities community about how digital archives have already and will continue to change how we search, access and work with newspapers as source material (Van House and Churchill 2008; Bingham 2010; Nicholson 2013). We also contribute to the wider project of developing more nuanced understandings of (digital) archives as both sources and subjects of history, as discussed by Yale (2015). She recently categorised the approaches of archival studies as understanding:

… archives as the product of decisions made by a range of stakeholders, from those who wrote the papers they contained, to the archivists who have processed and cared for them, to the state bureaucracies and officials who have determined which records were saved and which were destroyed, to the scholars who have excavated their contents over the years. No archive is innocent (2015, p. 332).

Though Yale omits mention of users and user studies of archives, some literature on this does exist (e.g. Duff 2012; Rhee 2012; Borteye and De Porres Maaseg 2013; McAvena 2017). Studies of the role of user analytics in digital archive selection choices, and the conceptualisations of “the user” that they point to, are little addressed in the wider literature. Discussions of user analytics in the archives, library and information studies literature tend to emphasise their role in identifying memory institutions’ impact; in evaluating social media strategies; and in user experience (UX) studies (e.g. Stuart 2015). Yet, it seems reasonable to expect that user analytics are or will be used to inform selection in a wide range of digital archives (not only newspaper archives but also other text-based, image, audio and multimodal digital archives). Fields like critical data science, digital humanities and information science are raising important questions about the benefits and dangers of user tracking and analytics, for example, of the ethical dimensions of using the increasingly fine-grained profiles of individuals that can be derived from the aggregation and mining of the numerous separate datasets that are generated as a result of the multiplicity of ways that individuals and groups are tracked while using digital platforms (see O’Neil 2017). The interface between this literature and that of studies such as ours, which draw attention to the role of user analytics in digital cultural heritage projects, is potentially a rich and important one. As such, we propose that this innovative aspect of our study may also open interesting perspectives for future studies of digital archives, while opening new conversations about the intersection of digital cultural heritage archives and the quantification of the individual and society.

Literature review and theoretical orientation

A large body of literature on archives has emerged from the fields of archival science, archival history and the archival turn in the humanities in recent years. This scholarship asks questions about the nature, purpose, composition and definition of archives. “Archives [can be read] as sources of history”, writes Yale, “but they are also its subjects, sites with histories and politics of their own” (2015, p. 332). Archives have been assembled to document and reinforce the identity narratives that individuals and nations tell about who they are (Stoler 2002). Likewise, the exclusion of the records of individuals and communities from archives can impact processes of inclusion and attitudes to belonging (Flinn et al. 2009). Archives can variously legitimise and destabilise oppressive political regimes (Aguirre and Villa-Flores 2015). They can give voice to, or silence, communities that were removed from traditional seats of professional, social, cultural or class-based power (Flinn 2007; De Kosnik 2016). Archives are not neutral but “at once express and are instruments of prevailing relations of power” (Harris 2002, p. 63).

What, then, of digital archives? An archive was once synonymous with dark and dusty physical locations. Yet, the concept of the ‘archival multiverse’ enfolds seemingly boundless and protean understandings of “[t]he pluralism of evidentiary texts, memory-keeping practices and institutions, bureaucratic and personal motivations, community perspectives and needs, and cultural and legal constructs with which archival professionals and academics must be prepared, through graduate education, to engage” (AERI and PACG 2011, p. 73). This definition opens the possibility of positioning large-scale collections of digitised cultural heritage materials as archives, as in this article. The questions of the archival turn are increasingly being asked of digital archives too, yet debates about how dynamics like power, nationhood and identity operate in and through digital archives have just recently begun (e.g. Thylstrup 2018). Users of digital archives are often invited to make use of seemingly discrete and complete archives while receiving limited information about their specific character—why material was chosen and curated, how it was obtained, and from which specific source material it was transformed into a digital copy. This has been decisively shown by Fyfe’s exposition of the invisibility of the corporate histories of digital scholarly resources from the public record (Fyfe 2016). In a similar vein, Gabriele has argued that “the residual layers of policy, practices and politics are utterly invisible in the digital record” (Gabriele 2003). The consequence of this invisibility, argues Mak, is the false impression that digital archives “have not only been protected from editorial intervention, but [that they] may even function outside traditional infrastructures of production” (Mak 2014, p. 1520). In this article we view digital archives as sites of potential knowledge production, where decisions about the inclusion and exclusion of digitised resources and the access to them that publics are afforded can have wide-ranging implications. As discussed above, the remediation of digital cultural heritage materials in binary format opens the possibility of bringing a wealth of digital tools and techniques to bear on them. The development of critical frameworks for scholarship with digital newspapers and digital cultural heritage materials that assist in helping researchers understand how and why collections take the form that they do are paramount to ensuring that such tools can be used to study them rigorously and appropriately.

Digital newspaper archives are appropriate for this study because they constitute a well-used and commonly provided body of digital objects. Newspapers have been the focus of large-scale digitisation projects and programmes, including public and commercial investments, and platforms. Large-scale newspaper digitisation programmes by national libraries and commercial companies began in the late 1990s, and have since grown exponentially in scope, scale and ambition (see Milne 2002; Smith 2006; Terras 2011; Gooding 2014, for histories). Europeana newspapers, for example, is funded by the European Commission and aggregates some 18 million historic newspaper images (Europeana Newspapers 2018a). The Bibliothèque nationale du Luxembourg has also digitised some 8,000,000 pages of Luxembourg newspapers and is making them available with a suite of “opensource software, tools and libraries” (Bibliothèque nationale du Luxembourg 2019). On the surface, the existing collections of national libraries, commercial companies, and, in some cases, public-private partnerships now offer an abundance of material for researchers and the interested public. National libraries, often in collaboration with regional or institutional libraries, have digitised and made publicly available large selections of their national newspaper archive, although digitisation coverage is patchy and far from complete (Nauta et al. 2017). Private companies have likewise invested in the digitisation of newspapers (Hitchcock 2016) as these have provided a lucrative business proposition for “genealogy and family history” (Gooding 2017, p. 60). Focusing our research on the choices made regarding the mass digitisation of newspaper collections has allowed us to consider multiple aspects of cultural heritage digitisation selection next to wider interests and concerns regarding the digital turn, and how it affects access to our past.

Methodology

This paper draws on a combination of semi-structured interviews with librarians, archivists and digital content managers; scholarly literature on newspaper digitisation; public facing material; and on grey literature from digitisation projects and providers in public institutions and commercial companies in Europe, North America and Australasia. 13 interviews with representatives from 7 public institutions and private companiesFootnote 1 were conducted between February and December 2018 in accordance with ethics procedures at Loughborough University (29 January 2018) and University College London (21st May 2018). Interviews were conducted in 2018 with representatives from the British Library (BL), the National Library of Scotland (NLS), the National Library of Australia (NLA) and the Koninklijke Bibliotheck (KB, the national library of the Netherlands). They were also conducted with the publishing companies Readex, ProQuest, and Gale, a Cengage Company (hereafter Gale). Informal discussions were held with staff at the BL and the NLA, followed by formal written questionnaires and summaries of the topics discussed; the remaining interviews were recorded via Skype. The National Library of Wales was contacted but was unable to offer an interview within the timeframe of this study.

Institutions and companies were selected in line with a purposive sampling approach, that is, one that seeks out “settings and individuals where … the processes being studied are most likely to occur” (Denzin and Lincoln 1994, p. 61). Within those institutions, we approached individuals who had been directly involved in some aspect of the digitisation of historical newspaper collections (for example, in the management, conceptualisation, technical elaboration and/or commercialisation of these collections).

The interview questionnaires that we developed sought to elicit information about:

the kinds of decisions that influence which newspapers are selected for digitisation;

how an institution understands the needs of its end-users;

how metadata standards are selected and applied;

metadata versionality, population and granularity;

the kind of access users are afforded in terms of information retrieval;

and interviewees’ reflections on avenues that are opened and closed by the digitisation process.

The semi-structured nature of the interviews meant that we could respond in an agile way to comments that interviewees made that we had not anticipated when we planned our core interview questions.

Interviewees received questionnaires, information sheets and consent forms via email in advance of interviews. This gave them the opportunity to discuss the questions with their line managers and other interested parties so as to avoid any potential mismatches between their responses and the policies of their respective institutions. All interviewees gave informed consent to participate in this study. Interviews were recorded but not transcribed in full due to lack of resources; rather, interviews were summarised from recordings by the project team. However, where direct quotations from interviews are used in this article, these are verbatim. Interviewees received these summary versions via email and were given the opportunity to clarify or provide addendums to their statements in advance of our analysis. This should not imply that our interviewees agree with the observations or findings of this article, but rather that they were given multiple opportunities to articulate their own observations.

We analysed the interviews according to an inductive, thematic approach. This involved an iterative process of reading the interviews, generating a tentative coding scheme, encoding themes, revising themes, defining and naming themes and the writing up of a narrative account of our findings (see Braun and Clarke 2006, pp. 83–97). The themes that we identified shape and structure the analysis, which also incorporates appropriate cross-references to the wider literature on newspaper digitisation. Although the institutions we approached fall broadly into two groups, commercial and public, each operates in a somewhat unique context, as detailed below.

Essential preliminary and contextual information

Readex, ProQuest and Gale are commercial publishing companies that have digitised extensive newspaper collections, access to which is sold via licensing to libraries and research institutions primarily. Readex has, since its founding in the early 1940s, especially focused on microfilming American historical newspapers, largely from the extensive collections of the American Antiquarian Society (Readex 2013; see also Meckler 1982). In the early 2000s, it moved into the digital provision of these newspapers (“History of Readex”, 2012). Although it partnered with the Center for Research Libraries in 2008 to create the World Newspapers Archive, with collections from Eastern Europe, South Asia, Africa and Latin America, its core revenue stream is centred on North American historical newspapers (ibid). Likewise, ProQuest has been digitising newspapers since the early 2000s, and has traditionally placed an emphasis on providing full runs of premium newspapers, which it sells on an individual basis (see “Products - ProQuest Historical Newspapers™”, n.d.). Amongst its most well-known titles are the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal, the Washington Post, and The Guardian (UK), but its collections are wide and varied, including regional American and other international English-language newspapers. Gale is perhaps best known for its early digitisation of The Times (UK) (Fyfe 2016, pp. 566–567) but now holds a portfolio of over 2000 titles in various historical collections. Other notable historical collections include the Daily Mail (UK), the Economist and the Financial Times as well as its extensive collection of eighteenth and nineteenth-century British newspapers (Gale 2019).

The Nineteenth-Century BL Newspapers collection is based on material obtained through legal deposit legislation as well as through some private donations, such as the Burney Collection (see “Burney collection”, n.d.). The digital collection is the result of a partnership with the BL and JISC in 2004, when Gale digitised the former’s microfilm collections from that period. The collection was released online in 2007 but has since undergone several iterations with different commercial providers. A detailed history of the BL’s newspaper digitisation programmes is well documented in Fyfe (2016) and Horrocks (2014). Since 2011, it has been in a partnership with the genealogy service FindMyPast to create and manage the online British Newspaper Archive (findmypast.co.uk, n.d). As a result of these partnerships with the private sector, access to these archives is via a subscription model and freely accessible only to users who are onsite at the BL premises in London or at partner libraries (using the BNA Community Edition). Currently, the BL newspapers are undergoing an additional round of digitisation, as part of its Heritage Made Digital programme (British Library 2018), in order to bring especially fragile or at-risk newspapers into the digital realm, again in partnership with FindMyPast but via an open-access model (British Library Board Business Plan, 2016–2017).

KB and the NLA began their newspaper digitisation programmes in the early 2000s (Holley 2010a; Janssen 2011). The former was created through the digitisation of both microfilm and original materials held in collections throughout Europe while the Australian collection was built upon existing microfilm from the Australian Newspaper Plan (Trove, “About”, n.d.). Both collections are held within larger national digital repositories, Delpher and Trove, and include a variety of print, manuscript and audio-visual material. Both databases are free to use and accessible to the general public. All newspaper materials in Delpher have been cleared for third-party copyright claims and released into the public domain. Trove has done this with most of its collection, and any data from in-copyright works are clearly identified on the web interface and in API results. KB collection is broken into six discrete periods of uneven lengths from 1618 to 1995, with “political, social, economic and cultural characteristics” relating to “the development of the journalistic profession and the newspaper sector” (“Selection Criteria”, 2008). It is the only collection that is actively shaped by an approach to press history that seeks to contextualise the development of the press itself through the titles selected.

The NLS is an outlier in the context of these interviews, as the library has not yet digitised any of their newspaper collections. It is currently scoping a newspaper digitisation programme and is applying for funding to do so (The Way Forward: Library Strategy 20-15-2020). The material that it seeks to digitise is based upon an existing directory from the microfilm era, the Newsplan Project, which identified at-risk newspapers and assessed them according to their preservation and conservation needs in the late 1980s and 1990s (“Newsplan Scotland”, n.d).

Findings

In the academic and professional literature on digitisation, it has long been acknowledged that it is not possible or practical to digitise all items in a collection (Hughes 2004, p. 32). Strategic approaches for selecting items are a core component of digitisation projects and are “influenced by a focus on the nature and intellectual content of the collections, their condition, and usage… and copyright status of the original materials” as well as institutional strategy (ibid; on selection mechanisms see also Hazen et al. 1998; Deegan and Tanner 2003; Terras 2008; Gertz 2013; Mills 2015). Yet specific details of newspaper selection can be difficult to uncover from respective digital newspaper archives. In the following, we reflect on the key themes about newspaper selection that emerged from our inductive analysis of interviews and, where appropriate, we connect these themes with wider academic discourses on newspaper digitisation. In doing so, we supplement the interviews that we conducted with additional information about selection that is in the public domain yet dispersed across numerous documents and websites.

As an outcome of our analysis, in the following, we divide selection criteria into two broad categories: ‘explicit selection’ (Sect. 4) and ‘implicit section’ (Sect. 5). Explicit selection covers intellectual and practical/technical criteria and involves decisions that directly determine whether a given source is selected for digitisation. We discuss this under the following headings: governance and advisory models; institutional strategies and aims; material matters; format availability; copyright; and business cases. It is worth bearing in mind that all these aspects are of course interrelated, and that the interviewees did not address these themes in isolation, but discussed them as part of a more encompassing discussion (see also Beals et al. 2020).

Governance and advisory models

In the first instance, the BL, the NLS and the NLA are all subject to government legislation that determines their corporate structure, which then influences selection rationale and digitisation strategy.Footnote 2 The digitisation strategy of the BL, for example, is approved by its Collection Management Group, and further by its Library Board. For their first newspaper digitisation project (December 2007), the British Library (BL) opened an online consultation with academics. Focus groups and user panel meetings were not held for the second digitisation project (July 2007–May 2009) because “almost any local title selected would be of interest to someone somewhere” (Shaw 2009, p. 10). The 2017–2020 strategy refines this somewhat, pushing for a focus on a “designated community” that now includes “all external users of Library digital collections and metadata”, from academics to “incidental communities” (“Sustaining The Value: The British Library Digital Preservation Strategy 2017–2020”, p. 2). This aim for breadth of coverage is mirrored by other national collections which have similar governance structures, for example the NLS Board and NLA Library Council.

The KB newspaper digitisation project is alone amongst those discussed to rely on a committee of press historians in the selection process (“Selection Criteria”, 2008). Yet the interests of particular groups, like academics, have shaped digitisation choices for key periods in national and press history. The rarity and historical importance of early newspaper collections was recognised by the BL, with its early digitisation of the Burney Collection; by KB, with its advisory committee’s particular reference to the period 1618–1800; and by Readex, through its collaboration with the American Antiquarian Society to digitise their unique collection of early American newspapers. Likewise, bespoke funding for projects relating to specific moments of public interest (such as the Dutch government’s recent push to preserve knowledge about the Second World War, and their selection of colonial newspapers) and even the choice to begin with what were perceived to be ‘obvious’ titles (for the BL this included the Examiner, Morning Chronicle and Graphic) (Shaw 2005, pp. 3–4), have skewed chronological representativeness on the grounds of their particular or disproportionate importance.

While commercial providers do not make their governance and advisory structure as clear, Readex advertises its collections as “selected by a distinguished academic advisory board” (“Readex America’s Historical Newspapers Collection to Surpass 1300 Titles”, 2007). A more extensive discussion of advisory boards to commercial companies is given below.

Institutional strategies and aims

Selection choices are informed by the longer-term aims of national institutions, details of which shape their digitisation strategies. The BL sought “UK wide coverage”, “century wide coverage”, works “out of copyright”, “complete runs”, a “mix of regional and truly local newspapers”, but also “inclusion of conservative press opinion via two important London papers (The Standard, Morning Post)”. This last criterion sought political balance in spite of the prevailing political landscape of the nineteenth-century press (Shaw 2009, p. 10). The NLA digitisation policy focuses on familiar elements, like cultural significance, but also seeks to preserve titles at risk from “carrier obsolescence” (“Collection digitisation policy”). The NLA’s offer to digitise on demand furthers this mutually beneficial relationship in making the newly digitised material a part of the public collection.

The digitisation strategy of the NLS indicates a commitment to “improv[ing] equality of opportunity by seeking to remove all barriers which prevent people accessing our collections and services”, with a specific focus on supporting curriculum, lifelong learning and professional development (“The Way Forward”, p. 7). KB’s objectives for 2015–2018 included a pledge that the customer “has access to as much digital content as possible, freely accessible to all to the greatest possible extent” (“The Power of Our Network”, p. 3). Allied to these objectives, the benefits of widened access were discussed by public providers in the interviews they give in terms of how digitisation can reduce the financial burden of researcher costs and is therefore justifiable as a public expense. These arguments, however, rest on the claim that the selection offered is fit for the purpose of research being undertaken—something that remains unclear given the ambiguous definition of “researcher”—an ambiguity, as evidenced in the BL defining its core users as “researchers of any kind”, that is inclusive and well meaning.

In the course of our interviews, it became clear that the best path to achieving the aims set out in the various digitisation strategies is often open to interpretation. Regarding geographical selection, for example, public institutions are associated with a particular nation or state and obliged to limit their remit accordingly, though this can be interpreted differently by institutions. While the BL has limited its digitisation efforts to titles that are within their collections and printed within the British Isles, KB has taken a broader view, gathering sources from several European nations to provide a representative sample of both the Netherlands and its former colonial holdings. The NLA, meanwhile, tried to align its geographical reach with its obligation to the Australian people, broadly defined, and to be reflective of Australia’s role in the Pacific. This gives them flexibility to digitise a wider range of Asian-Pacific titles thus supporting neighbouring countries in their digitisation initiatives. Representativeness within the nation is also conceived in different ways. While the BL and KB spoke of geographic representativeness in more general terms, the NLA collaborated formally with the state and territory libraries to achieve equal geographic representation. In the interview it stated that “[w]hen we started the digitisation process in 2007, the library deliberately chose one title from each state and territory to start the archive”. It left these initial selection choices to the partner libraries from those regions. Questions of population density and circulation were also addressed head on:

There have been some discussions around population size versus geographical spread; some stakeholder questioning why we haven’t done some of the larger metropolitan papers first when they would cover the “most people” but we argued that we didn’t just want to cover the metropolitan papers partly because we want to really understand Australian history (interview).

Delpher, likewise, chose titles based on the influence or longevity of a local or regional title, rather than the size of its local population, and the NLS will seek to encompass the “universe of Scottish newspapers”, as complete and encompassing as possible, regardless of the size, quality, influence or circulation of an individual newspaper.

Material matters

The availability of a complete, or near-complete run was also a commonly mentioned consideration when determining if a title would be included. ProQuest, for example, noted in the interview that they “always try to start with the very first edition of a newspaper, where available. Compare that with a programme such as Newsbank which always had a thematic approach … ProQuest specialises in full runs of newspapers and we sell each of them individually”. The BL and NLA also strive to obtain the most complete run possible from their own collections, though during the BL’s first digitisation process a decision was made to “tolerate and accept gaps in full runs and not to seek to fill these until later on” (Shaw 2005, p. 9). The availability of a complete run remained one of the selection criteria for the second batch (though this was taken to mean one issue per date, with no consideration of titles with morning and evening editions) (Shaw 2009, p. 11). While the NLA draws on the collections of collaborating institutions, completeness is still difficult because sourcing missing issues is a pain-staking and arduous task. KB, somewhat unusually, reported that it chooses the title based on other intellectual criteria first, then seeks out the most complete run available, whether in its own collection or elsewhere and whether in print or microfilm; they did not, however, generally mix separate collections to create a more complete sequence.

Mixing collections, occasionally seen in the Library of Congress’s Chronicling America database, is rare amongst public institutions, unlike commercial providers such as FindMyPast and Gale, who have negotiated third-party contracts to improve their digital holdings. Across all providers, if a long run of a publication cannot be obtained, it is usually deselected, regardless of other intellectual criteria in its favour. A future exception may be the BL’s Heritage Made Digital project, which aims to be more sympathetic towards shorter and partial runs. That obtaining complete runs is an intellectual rather than a practical criterion was particularly noted by the NLS, which stated that “whole title runs are essential” to the perceived integrity and value of the archive.

Nevertheless, at the NLA, “people can suggest titles to be digitised … We also have a contributor-funded model for people where they can suggest a title and provide a subvention towards to costs of that digitisation and we will digitise any paper they suggest that falls within our general selection guidelines, including copyright permissions” (interview) something likewise available through the National Library of New Zealand. Such models may prove vital to smaller archives and those in developing nations.

Format availability

The practical criteria that were discussed during interviews often concerned the conservation status of materials. Microfilm remains a stated preference or requirement for most digitisation projects (Library of Congress 2017). Some organisations, such as National Library of New Zealand, continue to microfilm new collections as an intermediary step prior to digitisation (National Library of New Zealand 2018). But in most cases, microfilm policies were developed and implemented with very different aims and concerns to today. In some cases, particularly the USA, microfilming was done as a replacement for conserving and maintaining original newspapers, and thus many originals simply no longer exist (Silverman 2014, p. 9).

All interviewees traditionally digitised from microfilm, despite concerns over variations in its suitability. According to KB:

Digitising from microfilm is cheaper than from the paper original. So, there was a policy to digitise from microfilm if that was available. But it has a drawback because the quality that you get from microfilm is much less than what you get from the original; mainly because most of the microfilms were made in the past using a high contrast technology … It is especially bad for the quality of the character recognition.

In the case of The Times, Gale stated in the interview that since they were responsible for rendering The Times as microfilm from 1785–2010, they were certain that its quality would be good enough to make it the basis of their digitisation programme. Yet, decisions made when The Times was first microfilmed have still directly shaped the extent of the Times Digital Archive and limit the new questions and methodologies that could otherwise have been applied to digitised materials. For example, the digital collection does not include Scottish and Irish editions, or more than one of the various editions released on a given day.

In our interviews, providers often referenced the more recent turn to direct digitisation of paper copies. This is driven by several factors, including unease about how the content of digitisation programmes was skewed in line with existing microfilm holdings. As a commercial publisher that relies upon meeting consumer demand, Readex for example stated that “everything that you publish should be based around the needs of users, not on what is available”. Practical concerns are also driving national institutions away from a microfilm first policy. Beyond the USA and New Zealand, microfilming projects have largely ceased. KB considers digital images stored in JPEG 2000 format to be archival quality and able to replace microfilming. Likewise, the BL’s Heritage Made Digital programme (British Library 2018) especially considers preserving at-risk or un-fit physical copies as a criterion for digitisation and the NLS stated their preference for future digitisation projects is to capture directly from newspaper hardcopy. Whether this preservation rationale outweighs financial pressures is difficult to ascertain. ProQuest stated that the cost of digitising historic newspapers, which may be fragile or otherwise vulnerable, can be prohibitive, a point that the public institutions do not deny. The NLS admitted in the interview that while digital capture of the hardcopy newspapers is its stated aim, “it will be challenging to resource” it. The NLA, on the hand, has begun to investigate best practices for large-scale hard copy digitisation partially to facilitate their subvention process but also because they have already digitised the majority of their existing microfilm stock. As for more recent newspapers, changes in journalistic practice have directly affected digitisation. Gale and ProQuest stated in their interview that they now secure born-digital PDFs directly from publishers, as did the public providers that act as legal deposit libraries for their respective nations (see also “The Legal Deposit Libraries (Non-Print Works) Regulations 2013”, n.d.).

Copyright

Another major practical concern of digitising newspaper content is copyright. Chronologically, the nineteenth century is particularly well represented in digital archives, owing perhaps to its ‘goldilocks’ (or just right) conservation-copyright status. Most pre-1900 material can be safely considered to be in the global public domain, yet 20th and 21st-century material is subject to legal ambiguities, even those maintained as part of a national legal deposit scheme. The BL specifies that the period 1800–1900 was initially selected for copyright reasons, though they nevertheless found that some owners of incorporated titles that were still in existence raised objections (Shaw 2005, p. 3).

The practical and legal costs associated with making these materials available impacts selection priorities. Gale noted during the interview that “there are a number of important historical sources that are in limbo because they are still in copyright and cannot be digitised as open-access material, but they are also not viable for a commercial company because they do not have name recognition”. Nonetheless, bespoke partnerships with copyright holders have allowed digitisers to overcome these difficulties. The NLA, in particular, discussed partnerships with key Australian publishers, noting that maintaining positive relationships with them and negotiating specific access conditions to digital or digitised material, allows them to provide their users with the best possible selection of titles.

A final practical point that shaped selection was avoiding duplication of effort, meaning libraries and digitisers could work together to create a fuller picture of the press rather than make their own collection ‘complete’. The BL conducted a consultation to avoid this (Shaw 2009, p. 11), while the NLS and NLA highlight this as a key concern in their collection development policies (“Collection development policy”, p. 3; “Collection digitisation policy”). KB maintains a continuously updated inventory of titles digitised by local and regional archives to avoid such duplication (“Selection Process”, 2008).

Making a business case

Fears around the privatisation of public heritage—the rise of exclusive, closed-access digital collections with undocumented selection processes and excessive subscription fees—have become common amongst digital humanists and academic librarians (European Union and Comité des Sages 2011; Prescott 2016). In our interview, Gale acknowledged the pushback they sometimes receive from scholars who argue that commercial scholarly publishers should have “no place in academic research at all”. Yet, the dichotomy of private versus public is less clear-cut than it may first appear. Selection, for all providers, is largely determined by the perceived audience for these newspapers and, more importantly, the economic relationship between this audience and the digitiser. This relationship is primarily characterised by the relative weight of the market value and the commons value of these heritage objects.

The perception of whether services should be provided by commercial or public institutions is usually dictated by the necessity of that service to the general public and the likelihood of monopoly (Kahn 1988; Common et al. 1992). Services that are required for the functioning of society but whose barrier to entry limits competition are often deemed natural public services; those that are necessary but easily provided by competing sources are natural private services. The level of necessity, regardless of the provider, sets the market value (Benington 2011). This market value might be paid directly by a consumer, or it might be translated into a commons value, distributed amongst both those who directly and indirectly benefit from its provision, utilising both tax-derived public funds and bespoke charitable donations, independent funding bodies or institutional trusts (ibid). In general, public providers place more weight on the commons value, conceptualising their work as “making a community’s documentary heritage widely accessible”, while private digitisers leverage its market value with consumers—to “recommodify an otherwise dead form, generating ‘new revenue from old news’” (Gabriele 2003).

Accordingly, in our interviews, ProQuest, Readex and Gale were all explicit in stating that their overarching aim is to monetise historical newspaper content and that this process affects selection practices. ProQuest, for example, noted that digitisation costs 50 cents per page, on average, and that some large newspapers can total 2–3 million pages of content. To recoup this outlay, ProQuest explained, they must select titles that can attract a sufficient commercial audience within the domestic US market, ideally drawing from global markets as well. Readex referred to their audiences’ “hunger” for the “rawest of raw materials”, their belief that newspapers remain the first rough draft of history. Gale did contend that some newspapers have not been commercially digitised because there is as yet no discernible market for them amongst key subscribers: genealogists, libraries and research institutions. ‘Yet’ is the operative word, however, and new evidence of audience interest can affect future content selection. Readex discussed how they analyse user-input search terms to identify emerging areas of interest and topics into which they wish to expand.

Public providers must also make an effective business case for digitisation, all the more so against a backdrop of austerity (see Morse and Munro 2015 on austerity and cultural heritage). The market value of digitisation remains part of the understanding between public institutions and their funders; the NLS pointed to the fact that “Scottish newspapers always top the list of user requests to be digitised” while the NLF noted that “taxpayers have paid for it and they have certainly got value for their money”, a sentiment echoed by interviewees at KB.

Our interviewees foregrounded their sense of responsibility to act as custodians of memory. The NLS described their intention to digitise Scottish newspapers in their entirety as a “gift” to the Scottish public. When commercial publishers cannot make a viable business case for the digitisation of a given newspaper title, public institutions can sometimes bridge the gap by recasting the market value into commons value. The NLS, for example, discussed how they:

have spoken to private providers … with regard to Scottish local titles. They are not seen as commercially viable. We are therefore confident that no one else is going to do this because the papers are too local—so we are not straying into anybody else’s territory.

Thus, many public institutions see it as their duty to fulfil a public service mandate and custodial role by digitising and making accessible those newspapers that are commercially unviable but that are part of the national heritage. This “great cultural service” appears to be recognised by users. The NLF state that, in response to their digitisation programme, people “greeted our personnel in the street and asked if we do understand the impact that it has for citizens in Finland” (Bremer-Laamanen 2009, p. 47). The NLA, meanwhile, characterised the mass engagement with crowd-sourced transcription (Holley 2010b) as the public’s attempt to “give back” to the library in gratitude for their digitisation programme, and admitted that their original API infrastructure had been “loved to death”, prompting upgrades in 2018.

Implicit selection, or the relationship between perceived audience and interface affordance

We discussed explicit selection, or the intentional inclusion and exclusion of newspapers from digital archives, above. Here we turn to implicit selection, or the way that users’ engagement with digitised material is mediated by the search and retrieval possibilities that are or are not made available to them via a given interface, thus supporting or constraining the questions that they can ask of the material. This, in turn, is further shaped by the affordances of the interface and the capabilities of different user groups. As we shall show, while intellectual and practical concerns have significantly shaped digital collections, they are also affected by conceptualisations of the intended audience, or market, for these collections. From our interviews it emerged that providers make decisions about the kinds of interrogation of digitised collections they will support, the interface through which material is made available, and the extent of paratextual or contextual data they release with reference to their understandings of their perceived audience. Thus, implicit selection cannot be considered independently of provider’s understandings of their user base. In this section, we discuss provider’s understandings and expectations of their user base, the forms of search and retrieval of their collections they support, and the methodologies and approaches that are currently in use to understand users and respond to their perceived needs.

User profiles

Although the economic relationship between provider and audience varied, and most providers aimed to serve a variety of users, there was a general consensus that the primary audience for digitised newspapers was the general public. Only KB pointed in their interview to a different core user: “academic researchers, especially in the field of the humanities”. While their actual user base appears to be much broader, with over a million unique visitors and 250 people applying to physically attend their “Public Audience (User) Day” in November 2018, this conceptualisation of their audience is unusual, and has shaped both their primary selection criteria and the interfaces through which users can obtain these materials.

Users are not necessarily understood as passive consumers of digital archival material. The BL, through its Labs initiative, has sought out and rewarded commercial and creative uses of their openly licence digitised materials through its annual awards programme, including music videos, table-top and video games and art installations (British Library 2019). Importantly, materials digitised in partnership with Gale and FindMyPast have largely been confined to entrants for the Research Award; winners of the Artistic and Commercial awards have focused entirely upon books, images and maps that have been made freely available in other BL collections (BL Labs Team 2019). Whether this is the result of licencing restrictions and costs, interface limitations and API access, or the selection decisions made is unclear, but the result is that while commercial criteria were often paramount in private and public-private selection choices, institutions selecting digitisation based on the intellectual or commons value of materials have had a wider economic impact, serving both the primary family history market and other unexpected use cases. With these issues in mind, the role of the user, as a possible market for the materials as well as an active agent in making productive use of them, requires more study (see Gooding 2017, p. 171).

Interviewees also pointed to what might be thought of as yet to be discovered user groups, such as the “creative industries, fashion students, crime writers, food and drink writers, app developers, sports enthusiasts”, who might be drawn into using digital newspaper archives in the future. Evidence of this being possible can be found in Australia, for example. The NLA has allowed and been impressed by commercial and creative uses of their materials, noting the expected use of “cutesy 1950s adverts” (interview) in promotional and creative works, but also unexpected uses, such as mobile applications providing historical Australian recipes and large-scale use of APIs by professional genealogists. Notable in the UK is the AHRC Creative Clusters program, which supports the development of new products and services in the creative industries, often by reusing digital resources.

Information search and retrieval

All of the commercial providers interviewed reported that they err on the side of the less experienced user when attempting to respond to the demands of a large and heterogenous user base. Whether in terms of information retrieval possibilities or interface design, providers tended to aim for simplicity. This was stated by Gale and also by Readex who conceive of the user as less experienced and uncomfortable with complexity:

fifteen years ago, our end user was a member of an academic library, a postgraduate student or faculty staff. That was the vision, and they are still amongst our best customers as they like our products. These days, however, more high school students and undergraduate students are using the collections, so we create different kinds of services in order to make it easier to use, including a more user-friendly interface.

During discussions about the difficulties of modelling bibliographical variances (like title changes, ownership changes and editions), interviewees stated their belief that the average user should not need to care about these issues. Readex noted that these concerns are “only for a high-end user, who is interested in this, but the average user should not have to deal with it upfront”. In other words, they reported a conscious choice to render invisible the complex decisions about newspapers that users are searching. In Readex’s view “it is about sorting out the scholarly questions–so that the reader does not have to deal with them”. In this way, information about digitisation and selection choices, along with archival and curatorial decisions about the underlying data are obfuscated from users in order to facilitate the prized ease of use and simplicity of access for “average” users (see e.g. Krug 2013).

In general, all providers worked under the assumption that detailed bibliographical information and the metadata that makes their collections machine readable is unnecessary for most users. There is a growing interest in “Collections as Data”, so this assumption may be proved wrong in time (Padilla 2018). Where detailed publication information exists, it remains within library catalogues or website description pages rather than being packaged with the digitised newspaper. Trove does provide URL links between its digitisation and catalogue records, and third-party users often provide this information via tags and lists. KB suggests that future efforts in the semantic web might better provide this data by linking external post-capture metadata development. The BL, meanwhile, is actively exploring the integration of bibliographical variances into its newspaper title records, though only as part of its in-house Heritage Made Digital programme.

Limited investment in enhanced metadata schemas is perhaps unsurprising given evidence of the primary use of these collections thus far. Digitisation has extended the reach of historic newspapers beyond the ‘usual suspects’ of academic researchers and genealogists, to user groups who did not traditionally undertake archival research and who engage differently with these archives. Yet Gooding (2017) points out that expectations that new user groups would fundamentally change the ways newspaper research is being conducted has not been borne out by extensive studies of user behaviour in commonly used large-scale digitised collections such as the British Newspaper Archive, Trove Newspapers and the Times Digital Archive. He notes “there is little evidence, however, that the majority … are using digitised newspapers for anything other than information discovery, browsing, and research” (2017, p. 128).

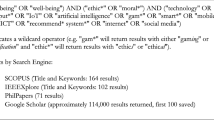

The interviews we conducted with commercial providers indicated that the traditional method of simple keyword searching is here to stay for the foreseeable future, since the majority of users have been habituated to this mode of search. Gale noted that their tracking of search behaviour online indicates that “most people will use a fairly general and bland generic keyword search, such as ‘murder’ or ‘World War II’” and that they subsequently will start to filter things down via facets, or the use of limiters. ProQuest also mentioned that reliable keyword searches remain central to the way in which users access their digital archives. Readex noted that it is currently working on improving keyword searches by installing auto-complete functionalities. It cautioned that “this is not spoon-feeding but it does make searching more efficient and efficiency is key to this form of research”. That Readex has no incentive to encourage or to develop more complex forms of search and discovery is borne out by user statistics. According to Gale, only around five per cent of their users make use of more advanced search functions like Boolean operators, proximity or fuzzy searching, even though these can provide more accurate results.

Compare this figure to the publicly owned Trove archive, which reported to us a much higher percentage of users who make use of advanced search functions. Half of its users use the Newspapers Advanced Search page, which ranks number two in views after Trove’s general homepage, ahead of the Newspapers landing page (private email from Trove to M. H. Beals). A contributing factor to this divergence may be that Trove was designed as an open, interactive and participatory forum from the outset. In addition to inviting users to suggest titles, they can create lists, leave comments, apply tags and submit text corrections. This has led to more nuanced ways of filtering the available metadata: “Someone researching a surname now has a whole range of functionality available for using Trove that we never originally envisioned but that the community has built itself: community-driven standards” (interview). Trove is therefore an example of how bottom-up repurposing and co-creation of tools and functionalities can open new ways of exploring large-scale archives despite the hurdles discussed by Mostern and Arksey (2016). Movement in this direction is anticipated by the BL and NLS, with the latter noting “One thing we need to explore is user tagging … We have had positive experiences with crowd-sourcing, and we are ramping up our volunteers to help us focus on tagging”.

These trends suggest that some providers will move beyond their current offerings and facilitate greater interaction and new forms of exploration, like cross-collection search and semantic web capability (see also Horrocks 2014; Moss et al. 2018). By the same token, if paying subscribers expect an archive that is easy to use, with a simple interface, then it is not surprising that user interaction will remain limited to this form of interaction. Digital platforms can support a plurality of approaches. So, it remains to be seen whether digital archives will continue to support relatively prescribed and limited modes of searching, browsing, and viewing newspapers alongside more advanced functionalities and what divisions will arise out of different funding models.

For users who are interested in the underlying meta and full-text data, both Gale and ProQuest occasionally provide OCR text for data mining on hard drives to existing subscribers to their wider offering, while KB, NFL, and Library of Congress provide data in compressed data files via their website, allowing for off-site analyses of public domain data. The NLA fully redeveloped its API in 2018 to provide a more streamlined big data experience (2018). Several providers are also experimenting with integrating data analysis tools into their collections. During our interviews, the NLA stated that “We are also working collaboratively to develop a humanities and social sciences virtual laboratory, which will connect to the API and other data sets and allow people to work just with the laboratory tools and not have to understand the API itself” while KB reported that “we are already thinking of creating a second user interface. A research interface. A Delpher Research Environment where we give more complicated options”. Both institutions note that these projects were being mooted in response to unexpected but welcome demand from the Digital Humanities community and the extent to which their collections have, as the NLA puts it, “really driven huge aspects of digital humanities research”.

Another commercial sector subscription model is Gale’s cloud-based “Digital Scholar Lab” (https://www.gale.com/intl/primary-sources/digital-scholar-lab). It was specifically designed for conducting digital scholarship and providing storage solutions for large-scale data as well as specific text-mining tools for professional users. While Gale admitted that working with large-scale data remains “a rarefied thing”, they clearly see potential and revenue in it. In general, however, digitisers do not currently see it as their remit to provide text-mining tools for researchers. ProQuest stated that its focus is on providing access to newspapers. Readex commented that its emphasis remains on the viewing and browsing experience of individual pages and that it aims to recreate as best as possible the original experience of encountering a historical newspaper in print through viewing tools that allow users high quality resolution of images of individual pages. Readex sees value in extending collections and adding new material because this is where they see continuous demand. One possible reason why Readex and ProQuest do not invest in platforms to facilitate the needs of large-scale data users is that they do not see a clear way to monetise this, which would incur significant costs given the incorporation of computing intensive tools into the main interface can considerably slow down the server response time. For this reason, Gale’s “Digital Scholar Lab” exists as a separate platform from the general interface and carries another subscription fee.

The algorithmic user: tracking and its consequences

Studies have drawn attention to the gulf that can exist between the perceived and actual needs of those who use digitised cultural heritage materials (Lynch 2003; Moss et al. 2018). As it stands, all our interviewees reported that they make use of qualitative and quantitative information about user behaviour to shape delivery methods. Next to collecting and analysing usage analytics, they reported that they regularly run focus groups and ask users to perform tasks like finding particular articles. Direct support via query forms and email is also available from all the providers we interviewed. These methods allow providers to identify different types of users, to draw up relevant documentation and tailor the scope and delivery of their collections. As indicted by the digitisation literature overview above, this marks a departure from traditional ways of choosing a collection to digitise, which has not tended to integrate user search terms as a driver. Moreover, this literature concentrates on institutional choices to make digitisation feasible, rather than the effect that these choices may have on users in the longer term.

During our interviews, we learned of the direct link between the arrangement and delivery of digital archives and the user-behaviour tracking that companies undertake, which demonstrated a market for ‘thematic’ collections rather than just particular titles. Readex explicitly links these collections to patterns that are detected in user analytics:

We have a large customer base and we mostly speak to them in the process of deciding on new collections. We mostly leverage the weblogs since they give us good insight into how the collections are being used and what users are searching for exactly. This gives us detailed insights into what topics are being searched and provides us with breakdowns of the usage patterns by regions and time of the year. Nowadays, we can show through the empirical data what users are interested in and locate where the gaps are.

Similarly, Gale is investing in thematic collections in response to user demand, as discussed during the interview. Due to increased interest in LGBT search terms and themes, Gale curated the Archive of Sexuality and Gender with the specific aim of supporting this type of research. Other factors were in play too. ProQuest presented thematic collections as a primarily commercial decision:

ProQuest digitised the NYT in the early 2000s and there are simply not enough comparable titles. So, we have to work with other titles or move more towards thematic collections … sometimes we only have partial runs of, for example six to eight newspapers, which we can then bundle together as a package.

Whether these collections are prompted by specific user behaviours or simply perceived marketability, the same questions regarding selection remain. The aforementioned Archive of Sexuality and Gender provides detailed information about the members of its respective advisory board, their backgrounds and their role in shaping the collection (2017). Readex also hires an advisory board for each of its new collections but noted in the interview that “the role of the advisory board is now more informal than it used to be”. Two factors account for this depreciation of the role of the advisory board. First, as Readex pointed out during the interview, they have gained much experience in building collections. Second, they noted their increased ability to obtain empirical data about what users are interested in either through weblogs or by talking to students and teachers. According to Readex, “those kinds of things inform us better now than any board of scholars could”. In contrast to Gale, information about who sits on the advisory board for each of these collections is not readily available on Readex’s websites or on the accompanying fact sheets for each of its collections. Thus, the perception of a core audience can dramatically affect the usability of the collection for all users. This connection between audience, feedback and documentation is further suggested by the fact that KB was the only public institution to point to the specific individuals on its advisory committee, listing them prominently on their website (2008), as a means of signalling to academics the credentials of the “Scientific Advisory Committee”.

This divide raises important questions about the role of academic expertise in the curation and use of these resources. Could the apparent turn away from scholars and archivists and towards the ‘algorithmic user’ result in limited offerings to what is expected and known instead of the longer-term thinking that is expected from cultural heritage institutions? In interviews, our respondents reflected on how previous selection choices could have less positive but lasting implications for scholarship. Part of this was owing to the trend that newspapers that have been digitised have been given more weight in some historical scholarship than material that has not. This has previously been highlighted in a study of digitised vs. non-digitised Canadian newspapers (Milligan 2013) which concluded that the enthusiastic uptake of digital archives by historians is “skewing our research” since digital sources are becoming more used than those newspapers that still exist in microfilm only or in print only, though this bias is rarely made explicit or problematised. In the interviews, Gale did recognise the ubiquity of The Times newspaper in scholarly research and suggested that this could be linked to the fact that it was one of the earliest newspapers available in digital format (see also Hobbs 2013). Positive, unexpected developments have been experienced too. Several of the interviewees and reports by other digitisers gave examples of how their collections had led to the accidental discovery of hitherto “unknown” manuscripts by a famous author, or the discovery of female authorship in historical newspapers that had been previously unacknowledged. For example, one graduate student at Houston University discovered in a ProQuest nineteenth-century newspaper database a lost novella by Walt Whitman which had been published in serial form in a New York newspaper in 1852. This rediscovered novella is now being reissued in print (NPR 2017).

Despite these initial indications, the exact relationship between perceived audience, selection choices, and user engagement is difficult to evaluate with clarity because of the degree to which selection of material and audience has been dictated by market or commons value. This is not always fully documented for, or understood by users, particularly in the case of public-private collaborations. Although generally described as a “partnership”, the public service mission does necessarily not carry equal weight amongst other selection rationale. Rather, interviews suggest that marketability to family historians and genealogists, who provide the main revenue stream for commercial companies, is given as the primary criterion. The BL noted in the interview that for “the British Newspaper Archive the driver is commercial, [we are] digitising primarily regional newspapers which will support family history research”. Despite this primary focus, the British Newspaper Archive’s website (2019) frames the project’s audience much more broadly, describing the archives as an “important initiative” that will ensure that researchers “from all over the world can access the treasures within it”. There is no mention of the underlying rationale of this digitisation project and no acknowledgement about the extent to which a particular set of paying users, namely genealogists, are factored into decisions about what is included in the archive. Even though the financial motivations of the commercial companies are openly acknowledged, the specific commercial concerns that have guided the digitisation choices remain obscure to the users of that archive. Moreover, without a full disclaimer, its association with the BL may lead users to believe this tailored collection is “authoritative” or “complete”. There are also several unexplored ethical issues regarding the proprietary status of user tracking information; are users made aware that their searches are being tracked beyond ubiquities cookie notifications and, perhaps more importantly, that they are informing the shape of future collections?

Conclusion: the digital newspaper archive for the future

This paper contributes to emerging understandings of factors that are rarely foregrounded yet shape the depth and scope of digital cultural heritage archives. The perspectives on selection, audience, and engagement raise new questions about the role and nature of digital newspaper archives. Our findings point to the complex interplay of internal and external interests and requirements to which newspaper selection rationale must be calibrated.

This research emphasises how new tools and functionalities are not a one-way street paved by the providers of digital archives, but are evolving in response to user-behaviour tracking and user demand in ways that are sometimes opaque. Digitised newspapers are not necessarily held in a complete, static and perpetually referenceable archive but bundled, and re-bundled, into thematic groups in response to the interests, and vagaries, of present-day users as expressed through search queries and bespoke requests and collaborations. The intended or expected users are a necessarily select group of people with a particular set of interests and, in ways that are largely unknown to them, their internalised knowledge is having a significant bearing on how the externalised information that is held in digital archives is being presented. National or regional contexts, as much as international markets, serve to inform and direct selection rationales. Far from offering users materials that may allow them to imagine and reimagine themselves and their societies anew, an imminent danger is that digital newspaper archives may come to perform a narrow understanding of culture and identity.

All repositories are inherently moulded and incomplete. But the growth of digital technologies, the essentially unlimited space available for documentation and metadata, alongside greater sensitivities to the constructed nature of archives, offers digitisers new opportunities. Digitisers can not only reconsider which audiences they are explicitly and implicitly serving but can also reflect upon specific interactions with their intended audience, selections and interface choices, and unexpected users in order provide clear and transparent documentation, not only to experienced and critical users of their collections, but through active promotion of the specific shape of these repositories to all users.

We therefore recommend that all digitisers of cultural heritage materials:

engage in critical (self-)reflection on the implicit and explicit selection criteria that shape their collections;

provide detailed selection rationale that inform users about the inclusion and exclusion of materials in and from the digital archive;

acknowledge and communicate the role that funding bodies, internal and advisory boards, user feedback, and tracked behaviour play in ongoing changes to collections or their access points;

inform users of how their actions are being tracked, and that future goods and services may be built upon this analysis of their behaviour;

Most importantly, this information should not be stored as an auxiliary report for the select few who request it but bundled with the digital archive as a living document that responsibly educates all users about the nature of the digital archive at every level of resolution—the collection, title, issue, article and corresponding metadata.

Ultimately, there is no one model for newspaper digitisation that is perfectly feasible and desirable across all audiences and providers. However, openness—not just honesty—enriches our understanding of our past and empowers users to undertake new, complex and unexpected commercial, scholarly, artistic and personal projects, that can only increase the market and commons values of these collections.

Notes

Further particulars about the interviews, and the schedule of interview questions asked of participants are available in the UCL research data repository: 10.5522/04/c.4812525.

See the British Library Act 1972, the National Library of Scotland Act 2012 (which replaced the 1925 Act of the same name) and the National Library of Australia Act 1960.

References

AERI (The Archival Education and Research Institute), PACG (Pluralizing the Archival Curriculum Group) (2011) Educating for the archival multiverse. Am Arch 74:69–101

Aguirre C, Villa-Flores J (eds) (2015). From the ashes of history: loss and recovery of archives and libraries in modern latin America. UNC Press Books

Beals MH, Bell E, with contributions by Ryan Cordell, Paul Fyfe, Isabel Galina Russell, Tessa Hauswedell, Clemens Neudecker, Julianne Nyhan, Mila Oiva, Sebastian Padó, Miriam Peña Pimentel, Lara Rose, Hannu Salmi, Melissa Terras, and Lorella Viola (2020). The Atlas of Digitised Newspapers and Metadata: Reports from Oceanic Exchanges. Loughborough. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.11560059

Benington J (2011) From private choice to public value. In: Benington J, Moore M (eds) Public value: theory and practice. Macmillan Education, London, pp 31–49

Bibliothèque nationale du Luxembourg (2019) Tools – BnL Open Data. In: Bibliothèque nationale du Luxembourg. Open Data. https://data.bnl.lu/tools/. Accessed 27 Oct 2019

Bingham A (2010) The digitization of newspaper archives: opportunities and challenges for historians 20 century. Br Hist 21:225–231. https://doi.org/10.1093/tcbh/hwq007

BL Labs Team (2019) Digital projects archive. In: Google Docs. https://docs.google.com/document/d/1Cs4hyNGq9Yi2mQdh1T3SN73e–zJ9dU-LntkOHNUMDc/edit?usp=drive_open&ouid=0&usp=embed_facebook. Accessed 1 Jul 2019

Borteye EM, De Porres Maaseg M (2013) User studies in archives: the case of the Manhyia Archives of the Institute of African Studies, Kumasi, Ghana. Arch Sci 13:45–54. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10502-012-9185-2

Braun V, Clarke V (2006) Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Research Psychol 3:77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Bremer-Laamanen M (2009) The present past: the history of newspaper digitisation in Finland. In: Walravens H (ed) Newspapers of the World Online: U.S. and international perspectives: proceedings of conferences in Salt Lake City and Seoul, 2006. Walter de Gruyter, New York, pp 43–48

British Library (2018) Heritage made digital. In: The British Library. https://www.bl.uk/projects/heritage-made-digital. Accessed 1 Jul 2019

British Library (2019) British Library Labs. In: The British Library. https://www.bl.uk/projects/british-library-labs. Accessed 1 Jul 2019

British Newspaper Archive. (2019) About. https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/help/about. Accessed 14 Jan 2019

Common R, Flynn N, Mellon E (1992) Managing public services competition and decentralization. Butterworth-Heinmann, Oxford

De Kosnik A (2016) Rogue archives: digital cultural memory and media fandom. The MIT Press, Cambridge

Deegan M, Tanner S (2003) Digital futures: strategies for the information age. Facet Publishing, London

Denzin NK, Lincoln YS (1994) Handbook of qualitative research. In: Denzin NK, Lincoln YS (eds) Sage, Thousand Oaks , London

Duff WM (2012) User studies in archives. In: Dobreva M (ed) User studies for digital library development. Facet Publishing, London, pp 199–206

European Union, Comité des Sages (2011) The New Renaissance, Report of the “Comité des Sages” Reflection group on bringing Europe’s Cultural Heritage online Read more: The New Renaissance, Report of the “Comité des Sages” Reflection group on bringing Europe’s Cultural Heritage online |. Reflection Group on bringing Europe’s Cultural Heritage online, Comité des Sages

Europeana Newspapers (2018a) Europeana newspapers—a gateway to European newspapers online. http://www.europeana-newspapers.eu/. Accessed 27 Oct 2019

Flinn A (2007) Community histories, community archives: some opportunities and challenges. J Soc Arch 28:151–176. https://doi.org/10.1080/00379810701611936

Flinn A, Stevens M, Shepherd E (2009) Whose memories, whose archives? Independent community archives, autonomy and the mainstream. Arch Sci 9:71–86. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10502-009-9105-2

Fyfe P (2016) An archaeology of victorian newspapers. Vic Period Rev 49:546–577. https://doi.org/10.1353/vpr.2016.0039

Gabriele S (2003) Transfiguring the newspaper: from paper to microfilm to database. Amodern 2: Network Archaeology:

Gale (2017) Archives of Sexuality & Gender: LGBTQ History and Culture Since 1940, Part 1 https://www.gale.com/intl/c/archives-of-sexuality-and-gender-lgbtq Accessed 31 Oct 2019

Gale (2019) Gale Historical Newspapers. https://www.gale.com/intl/primary-sources/historical-newspapers. Accessed 1 Jul 2019

Gertz J (2013) Should you? May you? Can you? Factors in selecting rare books and special collections for digitization. Comput Libr 33:6–11

Gooding PM (2014) Search all about it : a mixed methods study into the impact of large-scale newspaper digitisation. Ph.D., University College London (University of London)

Gooding P (2017) Historic newspapers in the digital age: ‘search all about it!’. Routledge, London

Harris V (2002) The archival sliver: power, memory, and archives in South Africa. Arch Sci 2:63–86. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02435631

Hazen D, Horrell J, Merrill-Oldham J (1998) Selecting research collections for digitization. Council on Library and Information Resources. Council on Library and Information Resources, Washington, DC

Hitchcock T (2016) Historyonics: privatising the digital past. In: Historyonics. http://webcache.googleusercontent.com/search. Accessed 8 Jun 2019

Hobbs A (2013) The Deleterious Dominance of The Times in Nineteenth-Century Scholarship. Journal of Victorian Culture 18:472–497. https://doi.org/10.1080/13555502.2013.854519

Holley R (2010a) Trove: innovation in access to information in Australia. Ariadne

Holley R (2010b) Crowdsourcing: how and why should libraries do it? D-Lib Mag. https://doi.org/10.1045/march2010-holley

Horrocks C (2014) Nineteenth-century journalism online—the market versus academia? Med Hist 20:21–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/13688804.2013.873159

Hughes LM (2004) Digitizing collections: strategic issues for the information manager. Facet, London

Janssen OD (2011) Digitizing All Dutch Books, Newspapers and Magazines - 730 Million Pages in 20 Years - Storing It, and Getting It Out There. In: Gradmann S, Borri F, Meghini C, Schuldt H (eds) Research and advanced technology for digital libraries. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, pp 473–476

Kahn AE (1988) The economics of regulation: principles and institutions. MIT Press, Cambridge

Koninklijke Bibliotheek (2008) Selection Criteria. https://www.kb.nl/en/organisation/research-expertise/digitization-projects-in-the-kb/databank-of-digital-daily-newspapers/selected-titles-and-selection-procedure/selection-criteria. Accessed 15 Jan 2019

Krug S (2013) Don’t make me think, revisited: a common sense approach to web usability, 3rd edn. New Riders

Library of Congress (2017) The National Digital Newspaper Program (NDNP) Technical Guidelines for Applicants. In: Library of congress. https://www.loc.gov/ndnp/guidelines/NDNP_201820TechNotes.pdf. Accessed 8 Dec 2018

Lynch C (2003) Colliding with the real world: heresies and unexplored questions about audience, economics and control of digital libraries. In: Bishop AP, Buttenfield BP (eds) Digital library use. MIT Press, Cambridge, pp 191–216