Abstract

Although it seems intuitively clear that candidate quality provides a critical pillar of democratic governance, the consequences of electing low-quality politicians remain unclear. Combining census data and election results, we conduct a regression discontinuity analysis to examine the socioeconomic effects of criminal politicians in India. We find that the election of state legislators with criminal charges can exacerbate household poverty in a village as household electrification and literacy rates both decrease when criminal candidates win close elections against non-criminal ones. In contrast, the presence of criminal politicians does not have a conclusive negative effect on the supply of local infrastructures, such as paved roads and power grids. These results highlight the importance of differentiating between different types of policy outcomes. Rent-seeking politicians will engage in local infrastructural projects, but they may pay little attention to these projects’ contribution to poverty reduction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Following Besley (2005), we distinguish between honesty/integrity and competence as the two principal dimensions of candidate quality.

See Section 5 to see the definitions of close elections.

See Section 4 for more discussion on the definition of serious crimes.

With a focus on India, Lee (2018) shows that the electoral victory of women politicians will lead to the provision of high-quality latrines.

Gehring, Kauffeldt, and Vadlamannati (2016) also seek to estimate the effect of electing criminal politicians into office on their legislative effort and the use of local development funds, but they focus on criminal politicians in Lok Sabha, the national parliament, instead of state assemblies.

In the Indian context, a robust democratic constitution and a series of anti-corruption laws imply that the legal system and regulations governing political activity are themselves of relatively high quality. The problem is that many politicians circumvent the rules and engage in illegal activities, and the criminal character of a politician is thus a good indicator of these inherent character traits. In contrast, in a country with biased laws on paper, willingness to break the law might not say anything about self-interest or a lack of respect for the rule of law.

Researchers have also noticed that some MLAs do not spend their allotted funds in constituencies. As Keefer and Khemani (2009) highlight, an MLA’s effort of delivering pork will be lower in constituencies when these constituencies are their party’s stronghold, perhaps because politicians would like to focus their resources on swing voters. We include fixed effects in our analysis to account for this caveat.

A positive scale effect does not mean that criminal politicians do not have an overall adverse effect. A positive local scale effect could come at the expense of areas governed by non-criminal politicians in a zero-sum game of resource allocation.

Here, of course, we must remember that such an increase in the number of projects does imply inefficient resource use and possibly the implementation of fewer projects in other areas of the country.

“Lawless Legislators Thwart Social Progress in India,” May 4, 2007, Wall Street Journal, available at http://www.wsj.com/articles/SB117823755304891604(accessed August 17, 2016).

The same concern also applies to the self-reported educational qualifications. See, for example, “5 Indian Politicians Shrouded in Fake Degree Scandals,” New Indian Express, June 9, 2015.

The ADR defines a serious criminal politician as a politician who has been charged with offenses that lead to five years or more in jail, offenses that are non-bailable, offenses that cause loss to exchequer, offenses related to electoral fraud, assault, murder, kidnap, or rape, and offenses included in the Representation of the People Act (Section 8) and the Prevention of Corruption Act. Serious criminal politicians also include those who have been charged with any crimes particularly against women.

Vaishnav (2017) follows a similar approach. Unfortunately, we cannot use data on actual convictions as opposed to pending charges. Criminal convictions against incumbent politicians are very rare in India and the legal process very time-consuming.

To clarify, here we only present five states where criminal politicians are most common, but the following analysis includes villages from the entire country.

Note the change of constituency boundaries in India after the March 2008 elections in Meghalaya. Using both administrative records and GIS maps of Indian boundaries, we have assigned every village in the country separately for pre-2008 and post-2008 constituency.

See Table A1 for the composition of our samples, both at the village and at the constituency level.

Alternatively, we address the concern of duplicated villages, which would otherwise result in the over-representation of some villages in the sample, by providing the results with a single round of elections. The results in Section A14 are very similar to our main findings.

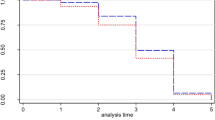

Given our focus on the local RDD, we do not include higher-order polynomials, as they may produce biased coefficients (Gelman and Imbens 2014). We estimate, instead, models that begin with the treatment variable alone, then add election year and state fixed effects, then add a linear local polynomial, and final include pre-treatment control variables. This approach ensures robustness and avoids noisy, potentially biased estimates based on complex functional form.

The 2011 Census recorded a household lacking assets if it owned none of the following items: radio, television, computer (or laptop) with Internet connection, landline telephone, mobile phone, bicycle, scooter, or car.

See http://www.myneta.info/ for more details.

In Section A6 (Supporting Information), we find the Imbens and Kalyanaraman (2012) optimal bandwidths and show that they are generally very close to 5%, thus validating our a priori decisions. We also apply different methods to see if our results vary by different optimal bandwidths (Hyytinen et al. 2018; Calonico et al. 2019); the results are very similar.

All table, figure, and section labels beginning with “A” are in Supporting Information.

Figure A6 shows that the effect on power supply of the serious criminal candidates is positive and sometimes statistically significant when we focus on the sample with the margin of victory smaller than 1%. This finding is still consistent with our proposed theory—that is, criminal politicians may have the incentive to provide local public infrastructure in pursuit of rents.

In Table A71, in the sample with the margin of victory smaller than 5%, we find that the interaction of “S criminal” with “alignment” is positive and statistically significant. This finding suggests that serious criminals are more likely to secure a village’s power supply when they are aligned with their respective chief ministers. However, in the same sample, which includes 18,981 observations with a serious criminal politician winning a close election, only 5,726 were aligned with their respective chief ministers.

The inspection includes items such as quality control arrangements, earthworks, side drains, road markings, surfacing, and pavement conditions.

See Section A10.

Table A18 (Supporting Information) shows the results based on serious criminal politicians.

Section A11 shows suggestive evidence for criminal candidates’ election contributing to more road agreements and higher rates of non-completion, but the estimates are mostly statistically insignificant.

The IHDS Project selected nationally representative samples in both rounds. See ihds.info.

References

Aidt T, Golden MA, Tiwari D. Criminal Candidate Selection for the Indian National Legislature. Working Paper: UCLA; 2015.

Alt J, de Mesquita EB, Rose S. Disentangling accountability and competence in elections: evidence from US term limits. J Polit. 2011;73(1):171–86.

Asher S, Novosad P. Politics and local economic growth: evidence from India. Am Econ J Appl Econ. 2017;9(1):229–73.

Baltrunaite A, Bello P, Casarico A, Profeta P. Gender quotas and the quality of politicians. J Public Econ. 2014;118:62–74.

Banerjee A, Green DP, McManus J, Pande R. Are poor voters indifferent to whether elected leaders are criminal or corrupt? A vignette experiment in rural India. Polit Commun. 2014;31(3):391–407.

Bardhan P. Corruption and development: a review of issues. J Econ Lit. 1997;35(3):1320–46.

Bardhan P, Mookherjee D. Decentralisation and accountability in Infrastructure delivery in developing countries. Econ J. 2006a;116(508):101–27.

Bardhan P, Mookherjee D. Pro-poor targeting and accountability of local governments in West Bengal. J Dev Econ. 2006b;79(2):303–27.

Barro RJ. The control of politicians: an economic model. Public Choice. 1973;14(1):19–42.

Besley T. Political selection. J Econ Perspect. 2005;19(3):43–60.

Besley T, Burgess R. The political economy of government responsiveness: theory and evidence from India. Q J Econ. 2002;117(4):1415–51.

Besley T, Montalvo JG, Reynal-Querol M. Do educated leaders matter? Econ J. 2011;121(554):F205–27.

Bohlken AT. Development or rent-seeking? How political influence shapes infrastructure provision in India. Br J Polit Sci 2019;online first.

Bose S. Transforming India: challenges to the world’s largest democracy. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 2013.

Brollo F, Nannicini T, Perotti R, Tabellini G. The political resource curse. Am Econ Rev. 2013;103(5):1759–96.

Calonico S, Cattaneo MD, Farrell MH, Titiunik R. Regression discontinuity designs using covariates. Rev Econ Stat. 2019;101(3):442–51.

Carnes N, Lupu N. What good is a college degree? Education and leader quality reconsidered. J Polit. 2016;78(1):35–49.

Caselli F, Morelli M. Bad politicians. J Public Econ. 2004;88(3–4):759–82.

Caughey D, Sekhon JS. Elections and the regression discontinuity design: lessons from close US house races, 1942-2008. Polit Anal. 2011;19(4):385–408.

Chemin M. Welfare effects of criminal politicians: a discontinuity-based approach. Journal of Law Economics, and Organization. 2012;55(3):667–690.

Dŕeze J, Sen AK. India: development and participation. 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2002.

Ferejohn JA. Incumbent performance and electoral control. Public Choice. 1986;50(1):5–25.

Fisman R, Schulz F, Vig V. The private returns to public office. J Polit Econ. 2014;122(4):806–62.

Gehring K, Kauffeldt T, Vadlamannati KC. Crime, incentives and political effort: a model and empirical application for India. Working Paper; 2016.

Gelman A, Imbens G. Why high-order polynomials should not be used in regression discontinuity designs. NBER Working Paper 20405; 2014.

Hyytinen A, Merilainen J, Saarimaa T, Toivanen O, Tukiainen J. When does regression discontinuity design work? Evidence from random election outcomes. Econometrica. 2018;9(2):1019–51.

Imbens G, Kalyanaraman K. Optimal bandwidth choice for the regression discontinuity estimator. Rev Econ Stud. 2012;79(3):933–59.

Imbens GW, Lemieux T. Regression discontinuity designs: a guide to practice. J Econ. 2008;142(2):615–35.

Jensenius FR. Development from representation? A study of quotas for scheduled castes in India. Am Econ J Appl Econ. 2015;7(3):196–220.

Keefer P, Khemani S. When do legislators pass on ‘pork?’ The determinants of legislator utilization of a constituency development Fund in India. In: Policy research working paper 4929. World: Bank; 2009.

Keefer P, Knack S. Boondoggles, rent-seeking, and political checks and balances: public investment under unaccountable governments. Rev Econ Stat. 2007;89(3):566–72.

Kenny C. Construction, corruption, and developing countries. World Bank, Policy Research Working Paper 4271; 2007.

Kramon E, Posner DN. Who benefits from distributive politics? How the outcome one studies affects the answer one gets. Perspectives on Politics. 2013;11(2):461–74.

Larcinese V, Sircar I. Crime and punishment the British way: accountability channels following the MPs’ expenses scandal. EPSA 2013 Annual General Conference Paper 924; 2013.

Lee DS. Randomized experiments from non-random selection in US house elections. J Econ. 2008;142(2):675–97.

Lee YJJ. Gender, electoral competition, and sanitation in India. Comparative Politics. 2018;50(4):587–605.

Lehne J, Shapiro JN, Vanden Eynde O. Building connections: political corruption and road construction in India. Working Paper: Princeton University; 2016.

Lewis-Faupel S, Neggers Y, Olken BA, Pande R. Can electronic procurement improve infrastructure provision? Evidence from public works in India and Indonesia NBER Working Paper 20344; 2014.

Magno CN. Crime as political Capital in the Philippines. Doctoral Dissertation: Indiana University; 2010.

Malhotra P, Jain P. MLA-LADS: a look into the loopholes and corrections. Centre for Civil Society Working Paper 2225; 2009.

Maskin E, Tirole J. The politician and the judge: accountability in government. Am Econ Rev. 2004;94(4):1034–54.

Mastrorocco N, Di Cataldo M. Organised crime within politics: evidence from Italy. Working Paper: London School of Economics; 2016.

Mauro P. Corruption and the composition of government expenditure. J Public Econ. 1998;69(2):263–79.

McCrary J. Manipulation of the running variable in the regression discontinuity design: a density test. J Econ. 2008;142(2):698–714.

Olken BA. Monitoring corruption: evidence from a field experiment in Indonesia. J Polit Econ. 2007;115(2):200–49.

Persson T, Roland G, Tabellini G. Separation of powers and political accountability. Q J Econ. 1997;112(4):1163–202.

Piliavsky A, editor. Patronage as politics in South Asia. New Delhi: Cambridge University Press; 2014.

Prakash N, Rockmore M, Uppal Y. Do criminal representatives hinder or improve constituency outcomes? Evidence from India. IZA Discussion Paper 8452; 2014.

Przeworski A, Stokes SC, Manin B. Democracy, accountability, and representation. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1999.

Sastry T. Towards decriminalisation of elections and politics. Econ Polit Wkly. 2014;49(1): 34–41.

Sharma V. Are BIMARU states still Bimaru? Econ Polit Wkly. 2015;50(18):58–63.

Snyder J, James M, Folke O, Hirano S. Partisan imbalance in regression discontinuity studies based on electoral thresholds. Polit Sci Res Methods. 2015;3(2):169–86.

Thube A, Thube D. Analysis of quality inspection reports of National Quality Monitors for PMGSY roads in India. International Journal of Structural and Civil Engineering Research. 2013;2(2):23–31.

Vaishnav M. When crime pays: money and muscle in Indian politics. New Haven: Yale University Press; 2017.

Weiner M. Party building in a new nation: the Indian National Congress. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1967.

Witsoe J. Everyday corruption and the political mediation of the Indian state. Econ Polit Wkly. 2012;47(6):47–54.

Woodall B. Japan under construction: corruption, politics, and public works. Berkeley: University of California Press; 1996.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic Supplementary Material

ESM 1

(PDF 761 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cheng, CY., Urpelainen, J. Criminal Politicians and Socioeconomic Development: Evidence from Rural India. St Comp Int Dev 54, 501–527 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12116-019-09290-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12116-019-09290-5