Abstract

Within a social hierarchy based on sexual orientation, heteronormative ideology serves as a social force that maintains dominant group members’ status (e.g., heterosexual men). Disgust may be an emotional reaction to gay men’s violation of heteronormativity (i.e., same-sex sexual behavior) and motivate hostile attitudes toward gay men to promote interpersonal and intergroup boundaries. Based on this theoretical framework, we hypothesized that sexual disgust—compared to pathogen or moral disgust—would be most strongly associated with antigay hostility and would statistically mediate its relationship with heteronormativity. Heterosexual men in the United States (n = 409) completed an online questionnaire assessing heteronormative ideology, disgust sensitivity, and hostile attitudes toward gay men. Results support the hypotheses and suggest that gay men’s sexual behavior is the most likely elicitor of disgust and antigay hostility, as opposed to a perceived pathogen threat or moral transgression. The findings indicate that heteronormative attitudes and sexual disgust are likely contributors to antigay hostility. Thus, intervention efforts should seek to improve tolerance of same-sex sexual behavior among heterosexual men, which may mitigate emotional reactions and hostile attitudes toward gay men.

Similar content being viewed by others

Disgust is an emotional reaction that is characterized by the revolution of environmental stimuli that is subjectively perceived as contagious, offensive, distasteful, or unpleasant (Rozin et al. 2008). Although the primary purpose of disgust is thought to aid the immune system by instituting a behavioral response of avoidance to protect against infectious diseases and other illnesses (Neuberg et al. 2011; Rozin and Fallon 1987), disgust also can be elicited from social stimuli, such as sexual acts and moral violations (Haidt et al. 1997; Rozin et al. 2008; Simpson et al. 2006; Tybur et al. 2009). Relatively recent research has begun examining disgust within intergroup contexts and how the emotion could produce hostile attitudes toward outgroup members (Cottrell and Neuberg 2005; Hodson and Costello 2007; Tapias et al. 2007). The current study, in particular, focused on the function of disgust as an emotional response to gay men as experienced by heterosexual men.

Three Domains of Disgust

Tybur et al. (2009) propose that there are three domains of disgust (i.e., pathogen, moral, and sexual), each of which is elicited from distinct stimuli and serves a particular function, but has a similar affective state of repulsion. Pathogen disgust is elicited in response to physical stimuli, such as mold, open wounds, and other vehicles of disease transmission, for which the emotional response protects against the ingestion of substances that may be physically harmful to the self (Neuberg et al. 2011; Rozin and Fallon 1987). For example, people who see mold on their food likely will experience pathogen disgust and, thus, remove themselves from the food by disposing of it in a trashcan. Pathogen disgust is particularly likely to be elicited within contexts in which pathogen threat is either immediately present or primed. Therefore, in situations where contagion is a salient threat, people are likely to behave in ways that diminish their risk (Tybur et al. 2014). An example can be seen through the general public’s reaction to the recent coronavirus outbreak. Persistent media messages of contagion appear to have created avoidance of public areas and aversions to interpersonal contact, and they may have even contributed to prejudicial attitudes toward individuals who are perceived as infected (e.g., Chinese-Americans; Kesslen et al. 2020; Kwai 2020). Pathogen disgust, in this context, may be the mechanism through which environment harvests behavior.

Moral disgust is the state of revulsion stemming from social transgressions, which includes an array of “universally” morally condemnable behavior (e.g., lying, cheating, and stealing). For example, observing a political leader deliberately manipulating constituents may elicit moral disgust and motivate negative attitudes toward, or removal of, the leader. Disgust in response to a moral violation is thought to promote avoidant behaviors toward violators because those who engage in immoral behaviors may be incapable of providing the reciprocity of benefits that are expected of in-group members. Instead, violators may be perceived to engage in costly interpersonal behaviors, such as stealing from, lying to, or more severe immoral behaviors such as killing (Tybur et al. 2009). Thus, avoidance of the violator may be self-protective. Within cultural contexts that are heavily influenced by religious ideology, such as politically conservative regions, sensitivity to moral disgust is prevalent (Rozin and Haidt 2013). This may be because religious and conservative communities often have larger variability in the types of behaviors that are perceived as immoral, relative to more secular and liberal communities (Haidt and Graham 2007). Therefore, moral disgust appears to be influenced by the stringency of traditional moral values.

The final domain of disgust, sexual disgust, can be defined in a number of ways. Tybur et al. (2009) suggest that sexual disgust is elicited from sexual stimuli and partners who may be biologically costly for reproductive success. Other researchers, however, offer a counter-conceptualization that may be favorable for researchers adopting a sociocultural perspective. Morrison et al. (2018) suggest sexual disgust is likely to be elicited among people who possess rigid notions of sexuality. Thus, sexual stimuli and behavior that fall outside of culturally normative conceptualizations of sexuality are likely to elicit sexual disgust. For example, men who engage in sexual activity with other men may elicit sexual disgust among people who rigidly adhere to traditional notions of sexuality. Therefore, cultural contexts in which there are stern sexuality and gender norms are likely to have high prevalence of sexual disgust sensitivity. When sexual disgust is elicited, it would be expected to promote interpersonal avoidance and hostile attitudes because associating with individuals who engage in behaviors outside traditional sexuality may be a threat to self-status within a social hierarchy (Kiss et al. 2018; this perspective is described in more detail in the following). Because we are primarily theorizing from a sociocultural perspective, we refer to sexual disgust as the conceptualization proposed by Morrison et al. (2018) moving forward.

Disgust toward Gay Men

Disgust as an emotional response to gay men is a phenomenon that has recently gained attention in the psychological and sociological literature. Initial work examining antigay attitudes suggests disgust is a common reaction to gay men and may reflect a prominent emotion in response to homosexuality (Herek 1986, 1988, 1993). Indeed, Embrick et al. (2007) identified disgust as a theme in qualitative interviews exploring working class men’s attitudes toward homosexuality in the workplace. More recently, research has begun to examine the outcomes of such emotional arousal. Several studies have presented results suggesting that people with increased disgust sensitivity report more antigay attitudes (Crawford et al. 2014; Inbar et al. 2009; Olatunji 2008; Terrizzi et al. 2010) and that the manipulation of disgust can amplify negative attitudes toward sexual minorities (Cunningham et al. 2013; Inbar et al. 2012). Meta-analytic findings have highlighted the robust association between disgust and antigay attitudes, with results indicating a moderate-to-large effect across studies (Kiss et al. 2018). Interestingly, there is some evidence to suggest that the effect of disgust on attitudes is larger in response to gay men than to lesbian women (Cunningham et al. 2013; Inbar et al. 2012), which may partially explain society’s generally greater dislike of gay men compared to lesbian women (Bettinsoli et al. 2019). Therefore, further research attentive to the influence of disgust on prejudicial attitudes toward gay men, in particular, seems warranted.

Behavioral Immune System

Researchers have sought to develop a theoretical framework to explain the particular function of disgust in response to gay men. Most research in the current literature utilizes the framework proposed by the behavioral immune system (Schaller 2006; Schaller and Park 2011). Theorists suggest that over the course of evolution, humans have developed a behavioral immune system to protect against novel pathogens that could cause harm. This cognitive system is tasked with identifying contamination threats and initiating cognitive, emotional, and behavioral responses that serve to mitigate such threats (Schaller and Park 2011). The primary way in which the behavioral immune system evokes adaptive behavioral responses is through the elicitation of emotion (Neuberg et al. 2011; Schaller and Park 2011). Situations in which there are contamination threats—such as interpersonal contact with unfamiliar groups—are likely to elicit disgust, which would motivate the development of hostile attitudes and behavioral avoidance (Schaller and Park 2011). These outcomes would be evolutionarily adaptive because they would decrease the likelihood of being exposed to deadly pathogens, which would bode in favor of the individual’s reproductive fitness and eventual reproductive success (Cottrell and Neuberg 2005). Proponents of the behavioral immune system suggest the framework can be adapted to explain disgust in response to gay men as well as subsequent antigay attitudes (Crawford et al. 2014; Inbar et al. 2009; Inbar et al. 2012; Terrizzi et al. 2010). Specifically, gay men may be perceived as vectors of parasites and their presence could evoke disgust as a mechanism to create boundaries (Crawford et al. 2014; Inbar et al. 2012; Terrizzi et al. 2010). The development of hostile attitudes would then aid behavioral avoidance by decreasing the likelihood of interpersonal contact with gay men (Inbar et al. 2012; Terrizzi et al. 2010).

If adopting a perspective attuned to the behavioral immune system, we could expect that pathogen disgust—compared to moral and sexual disgust—would be most closely linked to hostile attitudes toward gay men. Although this is certainly possible, other theoretical frameworks would suggest that disgust and antigay attitudes stem from gay men’s sexual behavior, implying that sexual disgust is most closely associated with hostile attitudes toward gay men. In the following we focus on the latter explanation. We outline a theoretical framework and describe an empirical study that tested the strength of association between the three domains of disgust and subsequent hostile attitudes.

Group-Based Social Hierarchies and Heteronormative Ideology

Group-based social hierarchies are present across many societies and can influence social groups’ access to resources and opportunities (Eldridge and Johnson 2011; Sidanius et al. 1994) as well as dictate the appropriateness of behaviors (Herek 2007). Theories concerned with group-based social hierarchies, such as social dominance theory (Pratto et al. 2006; Sidanius and Pratto 1999), suggest social hierarchies can be arbitrarily structured to systematically privilege or discriminate against groups based on characteristics such as race/ethnicity, nationality, religion, or sexual orientation. Several distinct social hierarchies (i.e., based on discrete attributes) can concurrently exist within a single society (Pratto et al. 2006). Each hierarchy is legitimized and justified through ideology (often referred to as “legitimizing myths”) that is deeply embedded in social institutions, intergroup processes, and individual attitudes (Herek 2007, 2016; Pratto et al. 2006). For example, ideology operating to justify social hierarchical structures can be reflected through governmental regulations or policies, preferential treatment of dominant group members, and individual prejudices or stigma toward “subordinate” or minority group members (Herek 2007, 2016; Herek and McLemore 2013; Pratto et al. 2006; Sidanius et al. 1994). Such ideologies, and their subsequent outcomes, are expected to disproportionately benefit the dominant group—compared to subordinated groups—at all levels of society (i.e., social institutions, intergroup processes, individual attitudes) in ways that serve to maintain dominate groups members’ status atop the social hierarchy (Herek 2016; Jost and Banaji 1994; Pratto et al. 2006).

Within the United States, researchers note the existence of a social hierarchy based on sexual orientation, which is maintained through heteronormative ideology (Hegarty et al. 2004; Herek 2007, 2016; Whitley and Ægisdóttir 2000). Heteronormativity can be conceptualized as an institutionalized social force that dictates acceptable behaviors based on the assumption that heterosexuality is normal (Habarth 2014; Kitzinger 2005; Yep 2003). That is, heteronormativity defines boundaries of “normality” and sets expectations for men and women to behave and express themselves in accordance with traditional gender norms (Habarth 2014). Although gender norms include general notions—such that men and women are expected to behave in a “masculine” and “feminine” manner, respectively—they also assume that men and women engage in heterosexual relationships and sexual behavior (Habarth 2014; Kitzinger 2005). In this way, individuals who strongly internalize heteronormative ideals conceptually intertwine gender and sexuality. Thus, heteronormative men are likely to perceive that they must engage in sexual behavior with women, and not men, in order to be sufficiently masculine (Herek 1986; Kitzinger 2005). Those who engage in behaviors outside of heteronormative ideals—such as people who engage in same-sex sexual behavior (e.g., gay men)—are presumed to be inferior, which could be used to justify their lower status (relative to heterosexual people) within a social hierarchy (Herek 2007, 2016; Whitley and Ægisdóttir 2000).

It is important to note that heteronormativity is conceptualized to encompass heterosexism (see Herek 2007, 2016) and heterocentric norms (see Hegarty et al. 2004), as well as more specific constructs relating to the embodiment of gender norms, such as heterosexual masculinity (see Herek 1986). Endorsement of heteronormative ideology has been associated with antigay attitudes and is argued to be the foundation of prejudicial attitudes toward gay men (Habarth et al. 2019; Harbaugh and Lindsey 2015). Some theorists suggest the resulting antigay attitudes are due to a perceived threat to the established heteronormative ideology (Herek 1986; Kiss et al. 2018; Parrott 2009; Parrott and Zeichner 2008; Theodore and Basow 2000; Whitley and Ægisdóttir 2000).

There are at least two ways in which gay men may be perceived as a threat in a heteronormative society. First, gay men may serve as a threat to the stability of society and social institutions that have historically favored heterosexuality (Kiss et al. 2018; Nagoshi et al. 2019; Whitley and Ægisdóttir 2000). Because gay men engage in sexual behavior that violates heteronormativity (i.e., same-sex sexual behavior), they could be seen to disrupt the ideology that maintains the arbitrarily set social hierarchy. This may be threatening—particularly among dominant group members who strongly adhere to heteronormative ideology—due to the more recent inclusion of gay men in American culture and institutions. Specifically, the inclusion of gay men in social institutions that had been previously reserved for heterosexual people (e.g., marriage) imply that norms are shifting and there is heightened openness to sexual behavior that falls outside the realm of heteronormativity. The credibility and inclusion of gay men is further evidenced by the recent historic presidential run by the first openly gay candidate, Pete Buttigieg (Fitzsimons 2020). Such a shift in norms could subsequently alter the social hierarchy in ways that no longer give structural preference to heterosexual people (Kiss et al. 2018; Nagoshi et al. 2019).

Second, gay men may threaten heterosexual men’s maintenance of characteristics that are consistent with heteronormativity (e.g., masculinity; Herek 1986; Parrott 2009; Parrott and Zeichner 2008; Theodore and Basow 2000). Nagoshi et al. (2019) explain that others’ deviations from normative gender behavior are a threat to the social status of the observer. This may be because heteronormative ideology prescribes stringent gender and sexuality norms (e.g., exclusive engagement in other-sex sexual behavior) for which men are expected to adhere if they wish to be considered sufficiently masculine by societal standards (Herek 1986). In some cases, proximity with violators of heteronormativity (e.g., gay men) may increase the likelihood of being misclassified as gay, thus threating the masculinity and social status of nearby heterosexual men. Consequently, heterosexual men may seek to avoid (Bosson et al. 2006; Bosson et al. 2011; Buck et al. 2013) or differentiate themselves from gay men by displaying antigay attitudes or behaviors (Bosson et al. 2011; Herek 2016; Parrott 2009; Parrott and Zeichner 2008), which would assist in preserving their individual status within a heteronormative social hierarchy. These ideas and empirical support indicate that gay men could perceivably threaten heterosexual men’s status at institutional and individual levels.

In response to the threats we outlined, disgust may be evoked as a self-protective emotion that motivates cognitions and behaviors aimed at mitigating threats to status within a social hierarchy. Hodson and Costello (2007) suggest that disgust can function to enhance intergroup boundaries and protect group status. More specifically, disgust evoked among high-status groups—in response to lower-status groups—would motivate hostile attitudes toward lower-status groups, which may produce systematic discrimination toward such groups. Thus, disgust would serve to exclude lower-status groups from social institutions and enhance group-based social hierarchies in favor of the dominant group. However, disgust reactions are stronger in response to gay men than many other social groups (Cottrell and Neuberg 2005; Crawford et al. 2014; Tapias et al. 2007), suggesting the emotion of disgust may be selectively induced in response to “threatening” social groups holding specific characteristics.

Crawford et al. (2014, p. 221) provide results demonstrating that disgust sensitivities among U.S. residents are most strongly related to negative attitudes toward groups who violate “traditional sexual morality,” such as gay men. Therefore, it seems sexual behavior that is beyond cultural norms may be particularly disgust-eliciting. In accordance with these data, it would be expected that gay men’s sexual behavior would be the disgust-eliciting stimuli producing hostile attitudes. Within a social hierarchy based on sexual orientation, gay men’s sexual behavior is in stark contrast to the ideology that maintains it (i.e., heteronormativity) and, thus, may be perceived as deviant, impure, or abnormal (Crawford et al. 2014; Herek 2007, 2016).

It is male-male sexual behavior, then, that could be threatening to heteronormativity and the stability of the social hierarchy. This should be especially true among heterosexual men who more strongly internalize heteronormative ideology because associations with gay men may threaten their presentation of masculinity (Herek 1986; Parrott 2009; Parrott and Zeichner 2008; Theodore and Basow 2000) as well as the social institutions that preserve heterosexuality as dominant (Kiss et al. 2018; Whitley and Ægisdóttir 2000). It also would be adaptively beneficial for heterosexual men who strongly internalize heteronormativity to develop increased sensitivity to sexual stimuli, which could be used to continually monitor violations and help to avoid emasculation and a deterioration of status. When encountering a violation of heteronormativity (e.g., gay men), disgust may be elicited as a threat response and initiate hostile attitudes to avoid or dissociate at an individual level (Buck et al. 2013), but also motivate social exclusion at an institutional level (Kiss et al. 2018).

The Current Study

Although some theoretical frameworks (e.g., behavioral immune system) would suggest pathogen disgust is most closely related to hostile attitudes toward gay men, theorizing from a sociocultural perspective would seemingly suggest that sexual disgust would be most strongly associated with antigay hostility. The current study tests these assumptions b examining the relationships among heteronormatively, disgust sensitivity, and antigay hostility. Based on frameworks proposed by group-based social hierarchical theories, we first hypothesized that sexual disgust sensitivity will statistically mediate the relationship between heteronormative ideology and hostility toward gay men (Hypothesis 1). Second, we expected that the indirect effect (i.e., statistical mediation) through sexual disgust would be significantly stronger than the indirect effects through pathogen disgust (Hypothesis 2) or moral disgust (Hypothesis 3). Finally, we hypothesized that heteronormativity will directly predict antigay hostility (Hypothesis 4).

Method

Participants

Participants were 409 exclusively heterosexual men living in the United States. Their average age was 31.66 (SD = 9.85) and ranged from 18 to 73 years-old (85.3% [n = 349] were 40 years of age or younger). A majority (314, 76.8%) of participants were European/White; 8.3% (n = 34) were Asian American; 6.6% (n = 27), Hispanic/Latino; 4.6% (n = 19), African American/Black; 1.7% (n = 7), Multiracial; and 2% (n = 8), other. The region of residence was diverse with participants living in the Southeast (25.7%, n = 105), Northeast (25.2%, n = 103), Midwest (20.8%, n = 85), West (20.5%, n = 84), and Southwest (7.8%, n = 32). Participants’ political ideology was normally distributed with a mean of 3.79 (SD = 1.66) on a 7-point scale from 1 (Very liberal) to 7 (Very conservative). A one-sample t-test indicated that the mean was significantly different from the midpoint anchor of 4 (i.e., “Neutral”), t(408) = −2.56, p = .011, which indicated the sample leaned liberal.

Procedure and Measures

Participants were recruited from Amazon Mechanical Turk (MTurk)—which is an online crowdsourcing marketplace—to complete an online questionnaire. Samples recruited via MTurk have been found to produce reliable data that is slightly more demographically diverse than standard internet samples and significantly more diverse than college samples (Buhrmester et al. 2011). A screening procedure was used to obtain a sample from the population of interest. Prior to being admitted access to the study’s questionnaire, participants were asked a range of demographic questions. The questions assessed the individual’s sexual identity, previous same-sex sexual experiences, gender, age, country of residence, and region of residence (as well as other demographic variables that were used to disguise the screener items). To be included in the study, participants must have reported they were (a) heterosexual, (b) do not have any same-sex sexual experiences, (c) male, (d) 18 years of age or older, and (e) live in the United States. Participants who did not meet these criteria were not given access to the study’s questionnaire. All study procedures were approved by the affiliated Institutional Review Board prior to the start of data collection.

Heteronormativity

The 16-item Heteronormative Attitudes and Beliefs Scale (HABS; Habarth 2014) is a self-report measure that assesses traditional attitudes and beliefs regarding sexuality and gender. Participants were asked to rate how strongly they agree or disagree with each of the statements on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). The scale contains items such as: “All people are either male or female” and “In intimate relationships, people should act only according to what is traditionally expected of their gender.” The mean of all 16 items represents participants “heteronormativity” score, with higher scores indicating higher levels of heteronormativity. HABS demonstrated excellent internal consistency in the current sample (α = .91).

Three Domains of Disgust

The Three-Domain Disgust Scale (TDDS; Tybur et al. 2009) is a self-report measure comprised of 21 scenarios that may be perceived as disgusting on one of three domains: pathogen, moral, or sexual. Participants were asked to rate each item on a scale from 1 (not at all disgusting) to 7 (extremely disgusting). The pathogen disgust subscale consisted of items that assessed sensitivity to physical stimuli associated with disease or illness, such as “Seeing some mold on old leftovers in your refrigerator” and “Sitting next to someone who has red sores on their arms.” The moral disgust subscale consisted of items that assessed sensitivity to morally condemnable behavior, such as “Stealing from a neighbor” and “Intentionally lying during a business transaction.” The sexual disgust subscale consisted of items that assessed sensitivity to sexual behavior, such as “Performing oral sex” and “Hearing two strangers having sex.” The mean of each subscale represents participants pathogen disgust, moral disgust, and sexual disgust score, respectively, with higher scores indicating higher levels of reported disgust sensitivity. The present sample produced adequate-to-excellent internal consistency for pathogen disgust (α = .81), moral disgust (α = .90), and sexual disgust (α = .79).

Antigay Hostility

The six-item Hostility subscale from the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule, Expanded Form (PANAS-X; Watson and Clark 1999) was used to assess antigay hostility. However, Parrott and Peterson’s (2008) revised instructions were used, which asked participants to rate the extent to which they experience each item in response to gay men, with response options ranging from 1 (very slightly or not at all) to 5 (extremely). Items include “Hostile,” “Scornful,” and “Loathing” and were randomly presented to participants alongside other items from the PANAS-X that are relevant for the revised instructions (e.g., items such as “Sleepy” would make little conceptual sense in this context and, therefore, were not included). The mean of the six-item subscale represents participants antigay hostility score, with higher scores indicating higher levels of antigay hostility. The Hostility subscale demonstrated excellent internal consistency in the current sample (α = .92).

Results

Data Preparation

Data were examined to assess missing data patterns and normality of each construct. A vast majority of participants (n = 338) did not have any missing data. However, 53 patterns of missing data emerged. No frequency of a missing pattern was greater than 4, suggesting the data was missing at random. In order to adjust for these instances of missing data, the maximum likelihood (ML) estimator was utilized. Normality was assessed by examining z-scores and calculating skewness and kurtosis indices for each construct. Constructs did not contain outliers and fell within estimates of normality (i.e., skewness ≤3.0; kurtosis ≤10) offered by Kline (2016).

Preliminary Analyses

Correlation coefficients, means, and standard deviations for all study variables can be seen in Table 1. Significant correlations include the positive associations between heteronormativity and antigay hostility, heteronormativity and sexual disgust, sexual disgust and antigay hostility, and among all three disgust constructs (i.e., pathogen, moral, sexual).

Confirmatory Factor Analysis

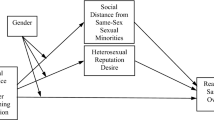

We conducted confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) in Mplus to examine the measurement of each variable. Prior to assessing the measurement model, parcels were created to construct latent variables. Each variable consisted of three parcels for which items corresponding to that variable were randomly assigned. Latent constructs containing parcels were used—as opposed to observed variables—to account for measurement error and control for order effects (Kline 2016). The model along with coefficients for each factor loading can be seen in Fig. 1.

Examination of model fit suggested mixed results. The Chi-square Test of Model Fit (ML χ2 [80] = 127.631, p < .001) suggested the model poorly fit the data. However, Chi-square Test of Model fit is sensitive to sample size and large samples increasingly accentuate minor discrepancies between the model and data (Barrett 2007; Kline 2016). Further, residual output and modification indices indicated strong correlations among parcels within each variable, which likely contributed to a significant Chi-square. This suggests other fit indices may better capture model fit. Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA = .038), Comparative Fit Index (CFI = .987), and Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR = .036) were examined and determined the model fit the data well (Kline 2016). Additionally, all parcels significantly loaded onto their corresponding factor and had standardized coefficients greater than .70. Given the generally good global and local fit, the measurement model was retained. Procedures for a fully latent structural equation model (SEM) were followed in subsequent analyses.

Hypothesis Testing: Structural Equation Model

The model presented in Fig. 2 was specified in Mplus for the structural model. Given significant observed Pearson correlations among all disgust constructs (i.e., pathogen, moral, sexual), these relationships were specified and resulted in a model containing specified relationships between all study variables. The model was perfectly identified and, therefore, has identical global fit to the CFA model. As we stated in prior section, the global fit indices of the model—with the exception of Chi-square Test of Model Fit—displayed good model fit (ML χ2[80] = 127.631, p < .001; RMSEA = .038; CFI = .987; SRMR = .036) and produced an R2 of .288 in antigay hostility (p < .001). However, a significant amount of residual variance for all study variables was not accounted for in the model.

We examined coefficients and p values for all paths which can be seen in Fig. 2. Of particular interest, heteronormativity predicted sexual disgust, but did not predict moral or pathogen disgust. Of equal interest, sexual disgust predicted antigay hostility, but neither moral nor pathogen disgust predicted antigay hostility. Additionally, all the disgust variables were significantly correlated with one another.

The direct effect of anger on heteronormativity was significant (the coefficient and p value are presented in Fig. 2). Indirect effects were calculated as the product of the unstandardized path coefficients from heteronormativity to antigay hostility through each of the disgust variables. The calculated indirect effects were examined within the model—using 1000 bootstrapped samples—as a new model constraint to allow for significance testing using a 95% bias-corrected confidence interval. Because the confidence intervals did not include zero, the indirect effect through sexual disgust was significant (β = .055, SE = .018, 95% CI [.021, .101]). In contrast, the indirect effect through moral disgust (β = .003, SE = .004, 95% CI [−.001, .018]) and pathogen disgust (β < .000, SE = .003, 95% CI [−.004, .008]) were nonsignificant because the confidence intervals included zero.

Direct and indirect effects were compared using a technique proposed by Lau and Cheung (2012). More specifically, unstandardized coefficients of each effect (i.e., direct or indirect) were, independently, subtracted from the effect being compared. For example, when comparing the indirect effect through sexual disgust to the indirect effect through moral disgust, the coefficient of the indirect effect through moral was subtracted from the coefficient of the indirect effect through sexual. The differences were then examined within the model—using 1000 bootstrapped samples—as a new model constrained to allow for significance testing using a 95% bias-corrected confidence interval. The indirect effect through sexual disgust was significantly stronger than the indirect effects through both moral (β = .052, SE = .018, 95% CI [.025, .097]) and pathogen disgust (β = .055, SE = .018, 95% CI [.029, .100]). There was no difference between the indirect effects through moral and pathogen disgust (β = −.003, SE = .005, 95% CI [−.019, .004]). Results also suggest that the direct effect from heteronormativity to antigay hostility was significantly stronger than any of the indirect effects: pathogen (β = −.214, SE = .041, 95% CI [−.292, −.133]), moral (β = −.211, SE = .042, 95% CI [−.294, −.129]), sexual (β = −.159, SE = .050, 95% CI [−.249, −.056]).

Discussion

The current study examined the relationship among heteronormative ideology, the three domains of disgust (i.e., pathogen, moral, sexual), and antigay hostility to test theoretical assumptions. Results indicated that the relationship between heteronormativity and hostility toward gay men was indirectly mediated by sexual disgust, but not pathogen or moral disgust. Further, the indirect effect through sexual disgust was significantly stronger than the indirect effects through pathogen or moral disgust. However, the direct effect from heteronormativity to antigay hostility was stronger than any of the indirect effects through the disgust constructs. These results suggest that theory surrounding the behavioral immune system may not adequately explain the phenomenon of antigay hostility. Rather, theory concerning group-based social hierarchies may provide greater insight.

More specifically, the framework posed by the behavioral immune system suggests that disgust responses and hostile attitudes toward gay men are the result of pathogen threat (Crawford et al. 2014; Inbar et al. 2009; Inbar et al. 2012; Terrizzi et al. 2010), whereas theory examining social hierarchies indicates a different hypothesis. Social hierarchical theories could lead to the logical assumption that gay men’s sexual behavior may be particularly disgust-eliciting and result in antigay hostility. It was conceptualized that group-based social hierarchies based on sexual orientation are maintained by heteronormative ideology (Hegarty et al. 2004; Herek 2007, 2016; Whitley and Ægisdóttir 2000), which communicates strict norms of sexuality and gender expression that favors heterosexual people (Habarth 2014; Herek 2007, 2016). Gay men’s sexual behavior could be perceived to violate heteronormativity (Kimmel 1997; Parrott 2009; Parrott and Zeichner 2008), which could threaten the stability of society and status of dominant group members (e.g., heterosexual men; Kiss et al. 2018; Whitley and Ægisdóttir 2000). Thus, disgust may be elicited and subsequently motivate cognitions and behaviors (e.g., hostile attitudes; social exclusion) that serve to enhance group boundaries (Hodson and Costello 2007).

Guided by the assumptions of the latter framework, we expected that sexual disgust would statistically mediate the relationship between heteronormativity and antigay hostility (Hypothesis 1) and that this indirect effect would be significantly stronger than the indirect effects through pathogen (Hypothesis 2) and moral (Hypothesis 3) disgust. These hypotheses were supported. The results support the notion that gay men’s sexual behavior is the most likely elicitor of disgust (Crawford et al. 2014), as opposed to a perceived pathogen threat or moral transgression (Morrison et al. 2018). More directly, our results suggest that the internalization of heteronormative ideology—and the stringent notions of “normal” sexual behavior that come with it—is positively associated with heterosexual men’s increased levels of sexual disgust sensitivity and antigay hostility.

One possible interpretation is that heteronormative ideology may lead heterosexual men to develop increased levels of sexual disgust sensitivity, so as to continually monitor their surroundings for violations of heteronormativity (e.g., same-sex sexual behavior) that are potentially threatening to their status (e.g., destabilization of social hierarchy; misclassification as gay). Consequently, such heterosexual men would be at increased risk to experience disgust in response to groups who engage in behavior that is outside of cultural norms (e.g., gay men; Crawford et al. 2014). Disgust would then aid the development of antigay hostility, which functions to protect the established social hierarchy (Hodson and Costello 2007; Kiss et al. 2018).

Although this is one conceivable explanation, others could be used to explain the relationships we found among variables—particularly the association between sexual disgust sensitivity and antigay hostility. For example, Tybur et al.’ (2009) theorizing suggests that the association between sexual disgust and hostility toward gay men is due to heterosexual men’s motive to avoid costly sexual advances from gay men. However, this explanation is not necessarily conflicting with the framework we have outlined. More specifically, sexual advances from gay men could increase the likelihood that bystanders would misclassify the heterosexual man as gay, thus threatening his social status and ability to attract an other-sex partner.

It also could be argued that sexual disgust sensitivity is most strongly related to antigay hostility due to the perceived pathogen threat associated with sexual intercourse, especially among gay men (Kiss et al. 2018). Indeed, antigay rhetoric often includes graphic depictions of gay men’s sexual behavior involving the exchange of fluids, contact with feces, and the typicality of it occurring in grimy bathrooms (Morrison et al. 2018), implying that pathogen infection is likely. Nonetheless, if antigay hostility were related to sexual disgust sensitivity due to risk of pathogen infection, we would expect pathogen disgust sensitivity to also be significantly associated with antigay hostility. Such an association was not supported by correlations or within the SEM in the current study.

Within other cultural contexts, it is possible that pathogens could be more prominently associated with gay men’s sexual behavior, which could alter the observed relationship among variables. For instance, during the peak of the HIV/AIDS epidemic in the United States—in which gay men were stigmatized as carriers of the disease (Herek 1999; Herek et al. 2005)—pathogen disgust may have had a stronger direct relationship with antigay hostility. This notion is supported by the established theoretical framework proposed by the Health Belief Model (Rosenstock 1974), which suggests health behavior is affected by an individual’s perceived susceptibility to a disease, the perceived seriousness of the disease, and perceived benefits and barriers to taking action (i.e., adjusting behavior). In the 1980s and 1990s, mass-media campaigns were introduced to alert the public to the seriousness of and their susceptibility to HIV/AIDS. These campaigns may have induced a change in behavior causing people—particularly with high levels of pathogen disgust sensitivity—to avoid risky sexual situations and people perceived as infected (e.g., gay men). Examining disgust sensitivity and antigay hostility in areas where gay men are particularly stigmatized as disease carriers—compared to areas where they are not—could be an insightful avenue of future research.

We also hypothesized that heteronormativity would be directly associated with antigay hostility (Hypothesis 4). This hypothesis was supported. These results provide further evidence for previous research suggesting heteronormative ideology is associated with antigay attitudes (Harbaugh and Lindsey 2015). The significant direct effect also suggests that disgust sensitivity does not fully mediate the relationship between heteronormativity and antigay hostility, highlighting the existence of other mediators between the two variables. The existing literature would benefit from additional research exploring the association between these two variables, such as their relationship to other theoretically relevant variables or how moderators could prevent the development of antigay hostility in men who reside in a heteronormative environment.

It is intuitive to wonder if the current study’s results generalize to attitudes toward other sexual minorities, such as lesbians. Although we were concerned with heterosexual men’s attitudes toward gay men, specifically, it is important to our theorizing to note that lesbians—who also violate heteronormativity ideals—do not pose a threat to heterosexual men’s status at the individual level; instead, lesbians only threaten heterosexual men at the institutional level (i.e., disrupt the social hierarchy maintained through heteronormativity). Due to the considerably smaller threat posed by lesbian women, it is expected that heterosexual men would have smaller disgust reactions to lesbians (but still experience some level of disgust) relative to gay men. Subsequently, heterosexual men should have less severe prejudicial attitudes toward lesbians compared to gay men. Because a majority of disgust research examining the two groups utilizes a conflated category, such as lesbians and gay men (Kiss et al. 2018), it currently is unclear if lesbians elicit less disgust than gay men. However, previous research indicates that men’s prejudicial attitudes toward lesbians, while extant, are less severe than they are toward gay men (Bettinsoli et al. 2019). Therefore, it is possible that lesbians pose a smaller threat to the social hierarchy and elicit less disgust than gay men, but this line of research is too young to make conclusions.

Limitations

Although the current study has numerous strengths (e.g., advanced statistical analyses; representation from all major United States geographical regions) that are often neglected within the relevant literature, it is not without limitations. Although directionality is constructed with theoretical considerations, an inherent limitation to cross-sectional survey research is that causality cannot be inferred. Second, the partial statistical mediation of disgust sensitivity suggests the existence of other variables within the relationship between heteronormativity and antigay hostility. Similarly, the third variable problem may be present for which a variable that was not considered may fully account for the observed relationships. A further statistical limitation is that the measurement and structural models failed to achieve exact fit (i.e., a non-significant value for the Chi-square Test of Model Fit).

The use of MTurk as a data collection tool also could be considered a limitation. MTurk tends to produce samples with higher levels of education and lower incomes than other online sampling methods (Levay et al. 2016). Additionally, the current data had an average political ideology value that significantly differed from the neutral midpoint (i.e., toward the liberal anchor); thus, the sample showed some evidence that it may have demographic deviations from the general population. Given the use of exclusively heterosexual men, it is unclear if the results could generalize to other groups of people (e.g., attitudes held by heterosexual women), which is another limitation. Last, although the association between disgust and antigay attitudes is robust (Kiss et al. 2018), the extent to which the emotion affects attitudes toward gay men in real world situations is unclear.

Future Research Directions

The current research highlights multiple avenues of future research. First, for a full understanding of the phenomenon, it is important for future research to continue investigation into why disgust is elicited in response to gay men. We outline theory suggesting that gay men’s sexual behavior may serve as a threat to status among heterosexual men. Experimental studies, such as those manipulating a masculinity threat from gay men, should consider measuring disgust as an outcome variable. This may provide additional evidence suggesting that one function of disgust is to enhance disparities in group-based social hierarchies.

Future research also may further compare the basis of disgust elicitors in response to gay men. In other words, is disgust truly stemming from gay men’s sexual behavior? If gay men’s sexual behavior is perceived to violate heteronormativity, thus eliciting disgust, we might expect exposure to violations (e.g., same-sex sexual behavior) to produce heightened levels of disgust. Experimental research could investigate this question by exposing participants to different levels of sexual contact between gay men and measuring participants’ emotional responses, as well as their antigay attitudes. Such future research would be incredibly beneficial to the understanding of antigay attitudes and may ultimately inform interventions that could mitigate its prevalence.

Practice Implications

The current study may have implications for researchers investigating the intersection between emotions and intergroup relations. As suggested by Morrison et al. (2018), very little research has focused on perceptions of gay men’s sexual behavior and how it relates to attitudes toward them. However, the results of the current study indicate that attitudes toward gay men are strongly associated with sexual disgust sensitivity, which suggests that the elicitation of disgust may be stemming from gay men’s sexual behavior. Therefore, increased research attention should be devoted to understanding perceptions of gay men’s sexual behavior and why it elicits disgust. We hypothesize that disgust is elicited because gay men’s sexual behavior violates heteronormativity, and this speculation is supported by the observed relationship between heteronormativity and sexual disgust sensitivity. In addition to advancing understanding of links among heteronormativity, disgust, and antigay attitudes, the current study also contributes to the current literature more broadly, which suggests that emotions have the ability to affect judgments, attitudes, and behavior toward certain social groups (DeSteno et al. 2004), particularly those who elicit such emotions (Tapias et al. 2007).

The current research also may have implications for interventions aimed at mitigating hostile attitudes toward gay men. Such interventions could find favorable outcomes by incorporating emotion-regulation constructs, which may provide individuals with healthy emotion-regulation strategies (e.g., increased ability to cognitively reappraise situations that elicit disgust), ultimately moderating the development of antigay hostility. Additionally, large-scale media campaigns focused on the normalization of gay men’s sexual behavior may lead to the eventual decreased adherence to heteronormativity, disgust reactions, and subsequent hostile attitudes toward gay men.

Conclusions

Although much of the research examining the association between disgust sensitivity and antigay hostility utilizes a theoretical framework proposed by the behavioral immune system, other theory might provide insight. Because so little disgust research has examined social hierarchies, we sought to outline why disgust would be elicited in response to gay men and how it would serve a functional purpose in this context. More specifically, gay men’s sexual behavior may elicit disgust among heterosexual men who strongly adhere to heteronormative ideology because it could threaten their social status. Subsequently, hostile attitudes may function to maintain the social hierarchy. Results more strongly support social hierarchical theoretical frameworks compared to the behavioral immune system. Thus, further empirical investigation into the interworking of social hierarchies, as well as the emotional mechanisms that legitimize them, is necessary.

References

Barrett, P. (2007). Structural equation modeling: Adjudging model fit. Personality and Individual Differences, 42, 815–824. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2006.09.018.

Bettinsoli, M. L., Suppes, A., & Napier, J. L. (2019). Predictors of attitudes toward gay men and lesbian women in 23 countries. Social Psychological and Personality Science. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550619887785

Bosson, J. K., Taylor, J. N., & Prewitt-Freilino, J. L. (2006). Gender role violations and identity misclassification: The roles of audience and actor variables. Sex Roles, 55, 13–24. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-006-9056-5.

Bosson, J. K., Weaver, J. R., Caswell, T. A., & Burnaford, R. M. (2011). Gender threats and men’s antigay behaviors: The harmful effects of asserting heterosexuality. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 15, 471–486. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430211432893.

Buck, D. M., Plant, E. A., Ratcliff, J., Zielaskowski, K., & Boerner, P. (2013). Concern over the misidentification of sexual orientation: Social contagion and the avoidance of sexual minorities. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 105, 941–960. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0034145.

Buhrmester, M., Kwang, T., & Gosling, S. D. (2011). Amazon's mechanical Turk: A new source of inexpensive, yet high-quality, data? Perspectives on Psychological Science, 6, 3–5. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691610393980.

Cottrell, C. A., & Neuberg, S. L. (2005). Different emotional reactions to different groups: A sociofunctional threat-based approach to “prejudice.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 88, 770–789. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.88.5.770.

Crawford, J. T., Inbar, Y., & Maloney, V. (2014). Disgust sensitivity selectively predicts attitudes toward groups that threaten (or uphold) traditional sexual morality. Personality and Individual Differences, 70, 218–223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2014.07.001.

Cunningham, E., Forestell, C. A., & Dickter, C. L. (2013). Induced disgust affects implicit and explicit responses toward gay men and lesbians. European Journal of Social Psychology, 43, 362–369. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.1945.

DeSteno, D., Dasgupta, N., Bartlett, M. Y., & Cajdric, A. (2004). Prejudice from thin air: The effect of emotion on automatic intergroup attitudes. Psychological Science, 15, 319–324. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0956-7976.2004.00676.x.

Eldridge, J., & Johnson, P. (2011). The relationship between old-fashioned and modern heterosexism to social dominance orientation and structural violence. Journal of Homosexuality, 58, 382–401. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2011.546734.

Embrick, D. G., Walther, C. S., & Wickens, C. M. (2007). Working class masculinity: Keeping gay men and lesbians out of the workplace. Sex Roles, 56, 757–766. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-007-9234-0.

Fitzsimons, T. (2020, March). The ‘Pete effect’: LGBTQ Americans reflect on Buttigieg’s historic run. NBC News. Retrieved from https://www.nbcnews.com/feature/nbc-out/pete-effect-lgbtq-americans-reflect-buttigieg-s-historic-run-n1147486.

Habarth, J. M. (2014). Development of the heteronormative attitudes and beliefs scale. Psychology and Sexuality, 6, 166–188. https://doi.org/10.1080/19419899.2013.876444.

Habarth, J. M., Makhoulian, S. C., Nelson, J. C., Todd, C. D., & Trafalis, S. (2019). Beyond simple differences: Moderators of gender differences in heteronormativity. Journal of Homosexuality, 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2018.1557955

Haidt, J., & Graham, J. (2007). When morality opposes justice: Conservatives have moral intuitions that liberals may not recognize. Social Justice Research, 20, 98–116. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11211-007-0034-z.

Haidt, J., Rozin, P., McCauley, C., & Imada, S. (1997). Body, psyche, and culture: The relationship between disgust and morality. Psychology and Developing Societies, 9, 107–131. https://doi.org/10.1177/097133369700900105.

Harbaugh, E., & Lindsey, E. W. (2015). Attitudes toward homosexuality among young adults: Connections to gender role identity, gender-typed activities, and religiosity. Journal of Homosexuality, 62, 1098–1125. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2015.1021635.

Hegarty, P., Pratto, F., & Lemieux, A. F. (2004). Heterosexist ambivalence and heterocentric norms: Drinking in intergroup discomfort. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 7, 119–130. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430204041399.

Herek, G. M. (1986). On heterosexual masculinity: Some psychical consequences of the social construction of gender and sexuality. The American Behavioral Scientist, 29, 563–577. https://doi.org/10.1177/000276486029005005.

Herek, G. M. (1988). Heterosexuals' attitudes toward lesbians and gay men: Correlates and gender differences. Journal of Sex Research, 25, 451–477. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224498809551476.

Herek, G. M. (1993). Documenting prejudice against lesbians and gay men on campus: The Yale sexual orientation survey. Journal of Homosexuality, 25(4), 15–30. https://doi.org/10.1300/J082v25n04_02.

Herek, G. M. (1999). AIDS and stigma. American Behavioral Scientist, 42, 1106–1116. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764299042007004.

Herek, G. M. (2007). Confronting sexual stigma and prejudice: Theory and practice. Journal of Social Issues, 63, 905–925. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.2007.00544.x.

Herek, G. M. (2016). The social psychology of sexual prejudice. Handbook of Prejudice, Stereotyping, and Discrimination, 2, 355–384.

Herek, G. M., & McLemore, K. A. (2013). Sexual prejudice. Annual Review of Psychology, 64, 309–333. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-113011-143826.

Herek, G. M., Widaman, K. F., & Capitanio, J. P. (2005). When sex equals AIDS: Symbolic stigma and heterosexual adults' inaccurate beliefs about sexual transmission of AIDS. Social Problems, 52, 15–37. https://doi.org/10.1525/sp.2005.52.1.15.

Hodson, G., & Costello, K. (2007). Interpersonal disgust, ideological orientations, and dehumanization as predictors of intergroup attitudes. Psychological Science, 18, 691–698. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01962.x.

Inbar, Y., Pizarro, D. A., Knobe, J., & Bloom, P. (2009). Disgust sensitivity predicts intuitive disapproval of gays. Emotion, 9, 435–439. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015960.

Inbar, Y., Pizarro, D. A., & Bloom, P. (2012). Disgusting smells cause decreased liking of gay men. Emotion, 12, 23–27. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0023984.

Jost, J. T., & Banaji, M. R. (1994). The role of stereotyping in system-justification and the production of false consciousness. British Journal of Social Psychology, 33, 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8309.1994.tb01008.x.

Kesslen, B., Ortiz, E., & Talmazan, Y. (2020, March). 10 ways the coronavirus is making people change their daily lives. NBC News. Retrieved from https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/10-ways-coronavirus-making-people-change-their-daily-lives-n1150811.

Kimmel, M. S. (1997). Masculinity as homophobia: Fear, shame, and silence in the construction of gender identity. In M. M. Gergen & S. N. Davis (Eds.), Toward a new psychology of gender (pp. 223–242). New York: Routledge.

Kiss, M. J., Morrison, M. A., & Morrison, T. G. (2018). A meta-analytic review of the association between disgust and prejudice toward gay men. Journal of Homosexuality, 67, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2018.1553349.

Kitzinger, C. (2005). Heteronormativity in action: Reproducing the heterosexual nuclear family in after-hours medical calls. Social Problems, 52, 477–498. https://doi.org/10.1525/sp.2005.52.4.477.

Kline, R. B. (2016). Principle and practice of structural equation modeling. New York: The Guilford Press.

Kwai, I. (2020, February). For a Chinese traveler, even paradise comes with prejudice. The New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2020/02/12/world/asia/china-coronavirus-korea-discrimination.html.

Lau, R. S., & Cheung, G. W. (2012). Estimating and comparing specific mediation effects in complex latent variable models. Organizational Research Methods, 15, 3–16. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428110391673.

Levay, K. E., Freese, J., & Druckman, J. N. (2016). The demographic and political composition of mechanical Turk samples. SAGE Open, 6. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244016636433.

Morrison, T. G., Kiss, M. J., Bishop, C. J., & Morrison, M. A. (2018). “We’re disgusted with queers, not fearful of them”: The interrelationships among disgust, gay men’s sexual behavior, and homonegativity. Journal of Homosexuality, 66, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2018.1553349.

Nagoshi, C. T., Cloud, J. R., Lindley, L. M., Nagoshi, J. L., & Lothamer, L. J. (2019). A test of the three-component model of gender-based prejudices: Homophobia and transphobia are affected by raters’ and targets’ assigned sex at birth. Sex Roles, 80, 137–146. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-018-0919-3.

Neuberg, S. L., Kenrick, D. T., & Schaller, M. (2011). Human threat management systems: Self-protection and disease avoidance. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 35, 1042–1051. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.08.011.

Olatunji, B. O. (2008). Disgust, scrupulosity and conservative attitudes about sex: Evidence for a mediational model of homophobia. Journal of Research in Personality, 42, 1364–1369. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2008.04.001.

Parrott, D. J. (2009). Aggression toward gay men as gender role enforcement: Effects of male role norms, sexual prejudice, and masculine gender role stress. Journal of Personality, 77, 1137–1166. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2009.00577.x.

Parrott, D. J., & Peterson, J. L. (2008). What motivates hate crimes based on sexual orientation? Mediating effects of anger on antigay aggression. Aggressive Behavior, 34, 306–318. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.20239.

Parrott, D. J., & Zeichner, A. (2008). Determinants of anger and physical aggression based on sexual orientation: An experimental examination of hypermasculinity and exposure to male gender role violations. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 37, 891–901. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-007-9194-z.

Pratto, F., Sidanius, J., & Levin, S. (2006). Social dominance theory and the dynamics of intergroup relations: Taking stock and looking forward. European Review of Social Psychology, 17, 271–320. https://doi.org/10.1080/10463280601055772.

Rosenstock, I. M. (1974). The health belief model and preventive health behavior. Health Education Monographs, 2, 354–386. https://doi.org/10.1177/109019817400200405.

Rozin, P., & Fallon, A. E. (1987). A perspective on disgust. Psychological Review, 94, 23–41.

Rozin, P., & Haidt, J. (2013). The domains of disgust and their origins: Contrasting biological and cultural evolutionary accounts. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 17, 367–368. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2013.06.001.

Rozin, P., Haidt, J., & McCauley, C. R. (2008). Disgust. In M. Lewis, J. M. Haviland-Jones, & L. F. Barrett (Eds.), Handbook of emotions (3rd ed., pp. 757–776). New York: Guilford Press.

Schaller, M. (2006). Parasites, behavioral defenses, and the social psychological mechanisms through which cultures are evoked. Psychological Inquiry, 17, 96–101.

Schaller, M., & Park, J. H. (2011). The behavioral immune system (and why it matters). Current Directions in Psychological Science, 20, 99–103. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721411402596.

Sidanius, J., & Pratto, F. (1999). Social dominance: An intergroup theory of social hierarchy and oppression. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Sidanius, J., Liu, J. H., Shaw, J. S., & Pratto, F. (1994). Social dominance orientation, hierarchy attenuators and hierarchy enhancers: Social dominance theory and the criminal justice system. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 24, 338–366. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.1994.tb00586.x.

Simpson, J., Carter, S., Anthony, S. H., & Overton, P. G. (2006). Is disgust a homogeneous emotion? Motivation and Emotion, 30, 31–41. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-006-9005-1.

Tapias, M. P., Glaser, J., Keltner, D., Vasquez, K., & Wickens, T. (2007). Emotion and prejudice: Specific emotions toward outgroups. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 10, 27–39. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430207071338.

Terrizzi, J. A., Shook, N. J., & Ventis, W. L. (2010). Disgust: A predictor of social conservatism and prejudicial attitudes toward homosexuals. Personality and Individual Differences, 49, 587–592. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2010.05.024.

Theodore, P. S., & Basow, S. A. (2000). Heterosexual masculinity and homophobia: A reaction to the self? Journal of Homosexuality, 40, 31–48. https://doi.org/10.1300/J082v40n02_03.

Tybur, J. M., Lieberman, D., & Griskevicius, V. (2009). Microbes, mating, and morality: Individual differences in three functional domains of disgust. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 97, 103–122. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015474.

Tybur, J. M., Frankenhuis, W. E., & Pollet, T. V. (2014). Behavioral immune system methods: Surveying the present to shape the future. Evolutionary Behavioral Sciences, 8, 274–283. https://doi.org/10.1037/ebs0000017.

Watson, D., & Clark, L. A. (1999). The PANAS-X: Manual for the positive and negative affect schedule-expanded form. Iowa City: University of Iowa. Unpublished manuscript.

Whitley, B. E., & Ægisdóttir, S. (2000). The gender belief system, authoritarianism, social dominance orientation, and heterosexuals' attitudes toward lesbians and gay men. Sex Roles, 42, 947–967. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1007026016001.

Yep, G. A. (2003). The violence of heteronormativity in communication studies: Notes on injury, healing, and queer world-making. Journal of Homosexuality, 45, 11–59. https://doi.org/10.1300/J082v45n02_02.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest for the manuscript and research.

Informed Consent

Human subjects were used for the current study. Informed consent was obtained prior to all participants’ engagement in the research.

Ethical Approval

All study procedures were approved by the Oakland University Institutional Review Board (Reference #1065292).

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ray, T.N., Parkhill, M.R. Heteronormativity, Disgust Sensitivity, and Hostile Attitudes toward Gay Men: Potential Mechanisms to Maintain Social Hierarchies. Sex Roles 84, 49–60 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-020-01146-w

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-020-01146-w