Abstract

Maritime cultural heritage is under increasing threat around the world, facing damage, destruction, and disappearance. Despite attempts to mitigate these threats, maritime cultural heritage is often not addressed to the same extent or with equal resources. One approach that can be applied towards protecting and conserving threatened cultural heritage, and closing this gap, is capacity development. This paper addresses the question of how capacity development can be improved and adapted for the protection of maritime cultural heritage under threat. It asserts that capacity development for maritime cultural heritage can be improved by gaining a more comprehensive and structured understanding of capacity development initiatives through applying a consistent framework for evaluation and analysis. This allows for assessment and reflection on previous or ongoing initiatives, leading to the implementation of more effective initiatives in the future. In order to do this, a model for classifying initiatives by ten parameters is proposed. It is then applied to a number of case studies featuring initiatives in the Middle East and North Africa region. This is followed by a discussion of how conclusions and themes drawn from the examination and evaluation of the case study initiatives can provide a deeper understanding of capacity development efforts, and an analysis of how the parameter model as a framework can aid in improving capacity development for threatened maritime cultural heritage overall.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cultural heritage is under increasing threat around the world, facing damage, destruction, and disappearance. While cultural heritage has long been subject to war and treasure hunting, new risks posed by twenty-first century problems such as sea-level rise, targeted terrorist attacks, and rapid population growth and urban expansion, make it progressively more vulnerable. Despite attempts to mitigate the threats to cultural heritage, threatened maritime cultural heritage is not addressed to the same extent or with equal resources as its terrestrial counterpart (Firth 2015; Flatman 2009).

The core of the gap results from a lack of awareness about the problems that maritime cultural heritage faces, terrestrial heritage often being more visible and recognizable. This fits into the larger issue of sea blindness, a multidisciplinary concept meaning the absence of awareness and knowledge about the oceans (Redford 2014; Firth 2015). Consequently, priorities for conserving and protecting cultural heritage lie elsewhere, and funding and resources are channeled into addressing these threats. Rising From the Depths, funded by the Global Challenges Research Fund and the Arts and Humanities Research Council of the UK Government to promote maritime cultural heritage as a means to develop sustainable growth in East Africa, asserts that “Globally, the potential and importance of MCH [maritime cultural heritage] has not yet been realised anywhere…we are losing the resource before we have had a chance to harness its potential” (Rising From the Depths 2018). This is compounded by a lack of resources (funding opportunities and infrastructural support) and knowledge (smaller body of expertise and skill) compared to what is available in support of terrestrial cultural heritage.

One approach towards protecting and conserving threatened cultural heritage is capacity development. Capacity development is a process that allows for an individual, institution, or communities to participate in the sharing or transfer of knowledge and capabilities in order to more effectively carry out work and projects (UNDP 2009; World Bank Institute 2009; OECD 2006; see below). It has become a commonly used approach in the cultural heritage field and has achieved results in the protection and conservation of threatened cultural heritage. While capacity development has primarily been employed for the protection and conservation of threatened terrestrial cultural heritage, it has the potential to be applied as a strategy in support of threatened maritime cultural heritage.

This paper suggests that to date programs of capacity development have been implemented within a context that does not necessarily reflect on previous experiences or draw on models of effectiveness. As such it addresses the question of how capacity development can be improved and adapted for the protection of maritime cultural heritage under threat. It asserts that capacity development for maritime cultural heritage can be improved by gaining a more comprehensive and structured understanding of capacity development initiatives through applying a framework to evaluate and analyze initiatives. This would allow for the assessment of, and reflection on, previous or ongoing initiatives, and the design and implementation of more effective initiatives in the future.

In order to accomplish this, a review of how capacity development broadly functions for both terrestrial and maritime cultural heritage under threat, is presented. A model for classifying initiatives by parameters is proposed and then applied to a series of case studies. This is followed by a discussion of how conclusions drawn from the examination and evaluation of the case study initiatives can be applied to capacity development efforts and an analysis of how the parameter model as a framework can aid in improving capacity development for threatened maritime cultural heritage.

Background

Definitions

For the purposes of this paper, it is important to establish from the outset clear definitions for capacity, capacity development, and capacity building, as they are employed across multiple fields and as a result, definitions tend to be varied and broad. The definitions chosen are those used by major institutions engaged in capacity development.

The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) defines capacity as “the ability of people, organisations and society as a whole to manage their affairs successfully” (OECD 2006). The European Commission breaks it down further as “the ability to perform tasks and produce outputs, to define and solve problems, and make informed choices” (Europe Aid 2005).

Capacity development is defined by the United Nationals Development Programme (UNDP) as “the process through which individuals, organisations and societies obtain, strengthen, and maintain the capabilities to set and achieve their own development objectives over time” (UNDP 2009). It can also be understood in ways that stress local initiative, such as in the World Bank’s definition: “capacity development is a locally driven process of learning by leaders, coalitions and other agents of change that brings about changes in socio-political, policy-related, and organizational factors to enhance local ownership for and the effectiveness and efficiency of efforts to achieve a development goal” (World Bank Institute 2009). Other definitions emphasize the on-going nature of capacity development and the need for sustainability over time.

Capacity building is interrelated to capacity development. Some organizations use the terms interchangeably, while others consider them to mean different things. The UNDP describes capacity building as “a process that supports only the initial stages of building or creating capacities and alludes to an assumption that there are no existing capacities to start from. It is therefore less comprehensive than capacity development” (UNDP 2008). The OECD affirms this; “the ‘building’ metaphor suggests a process starting with a plain surface and involving the step-by-step erection of a new structure, based on a preconceived design” (OECD 2006). “Capacity development” will thus be the preferred term used in this paper, as capacity building will be assumed to fall within the larger scope of capacity development.

How Capacity Development Works

There are numerous ways in which capacity development can be implemented but there are certain theories or processes which characterize contemporary efforts. First, there are interconnected levels of capacity, that is the “enabling environment”, that operate at societal, organizational or institutional, and even individual, levels (UNDP 2008, 2009; OECD 2006; Fukuda-Parr et al. 2002) Effective capacity development initiatives must engage with all levels to create lasting structural change (Fukuda-Parr et al. 2002).

Next, there are the donors and recipients. Capacity development requires donors (who provide the knowledge and support) and the recipients (who are receiving and implementing it). The ideal relationship between the two should not look asymmetric, there should be an interplay between the two, with recipients initiating and directing, and donors facilitating and critiquing (Fukuda-Parr et al. 2002; UNDP 2008). A variety of stakeholders may be donors and recipients—national governments and governmental departments, public and private sector organizations and institutions, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), universities, and communities.

A goal (or goals; often referred to as ‘development goals’) must be clearly articulated in order to achieve efficient and effective capacity development (UNDP 2008, 2009). These can be focused on impact: “change in people’s well-being,” outcome: “change in institutional performance, stability and adaptability,” output: “product produced or service provided based on capacity development core issues (institutional arrangements, leadership, knowledge, and accountability),” or an amalgamation of the three (Capacity Development Group, Bureau for Development Policy 2010). Goals are implemented through a process, with each differing depending on the type of capacity being developed and stakeholders involved. International agencies have created standardized frameworks that are widely used. The UNDP and the World Bank are two notable examples (UNDP 2009, n.d.; World Bank Institute 2009).

Finally, it is crucial that there is a framework for evaluation in place (UNDP 2008). Capacity should be assessed both prior to and after implementing an initiative to ensure success. Evaluation should take place at all levels and consider a wide range of factors, from concrete outcomes of the initiative to long term sustainability (UNDP 2008; World Bank Institute 2009).

Capacity development is a useful tool precisely because of its adaptability to a variety of fields and its customizability based on aims and objectives. These qualities have allowed capacity development to be applied across disciplines, including cultural heritage management.

Capacity Development and Threatened Cultural Heritage

Capacity development is used extensively in cultural heritage management and related disciplines. Much of current capacity development within the cultural heritage sphere addresses the issue of heritage under threat. Major threats include armed conflict, the illicit antiquities trade and looting, natural hazards and climate change, urban development and unsustainable tourism, and negligence and disregard. Maritime specific threats include the natural (environmental processes, climate change effects) and the man-made (coastal and offshore development and construction, marine industry including fishing, conflict, looting, tourism, and agriculture).

This is not the place to attempt to summarize capacity development for the cultural heritage field as a whole, and there is no one unified approach for how best to develop or build capacity in response to these threats as their nature and scope vary widely. Initiatives are not confined to one area of the world, although certain threats impact specific geographic regions more heavily than others. There is also frequent overlap between capacity development methods adopted depending on the nature of the threat, as well as between capacity development programs in other fields.

There are a number of issues which make developing capacity to safeguard threatened cultural heritage challenging. One of the greatest challenges is the lack of baseline capacity which makes developing, building, and effectively implementing capacity, even more difficult. This is true at all levels (international, national, and local). In many cases, capacity needs to be built from the ground up, as there is often little or no framework in place. An additional challenge is the capacity to deliver, currently the need is invariably greater than the ability (British Council 2017; ICOMOS 2006; Machat et al. 2014). Cultural sensitivity is also needed. There can be a difference between the donor’s ideas of what cultural heritage is worth protecting and what heritage the recipient is concerned about. This is especially relevant for partnerships between Western countries and those that are former colonies or the global south. Local attitudes and knowledge must be considered in order for capacity development projects to have long term success (ICCROM 2015). Additionally, countries or areas facing serious threats such as armed conflict or natural hazards are often primarily concerned with safety and security for their people, rather than the protection of the past, and funding for projects may instead go to international development or other fields that are seen as more urgent. It can also be dangerous to work in some areas, thus curtailing efforts from both those already within the country/region and the arrival of those from elsewhere. Finally, long term results are difficult to measure. Success is hard to quantify and there is often no follow up over the long run leading to a lack of feedback and understanding of the impact of many initiatives. Feedback is beneficial not only to evaluate whether an initiative worked well, but also to design effective future initiatives. For maximum impact, initiatives need to not just be effective in the short-term, but have sustainable outcomes lasting over a long period of time (UNDP 2008, 2009; OECD 2006; Fukuda-Parr et al. 2002).

Capacity Development for Threatened Maritime Cultural Heritage

Capacity development’s utility as a tool for protecting maritime cultural heritage often draws on knowledge and skills transferred from terrestrial cultural heritage. A large repository of expertise and resources related to terrestrial cultural heritage already exists and can be applied to capacity developing efforts directed towards maritime cultural heritage. There is also a growing body of knowledge and skills directly related to maritime cultural heritage that can be harnessed. Furthermore, it is possible to fit maritime cultural heritage initiatives into previously existing environmental sustainability or international development initiatives, which may have more opportunities for funding and greater awareness of need. Certain types of maritime cultural heritage (shipwrecks, for example) may generate greater awareness by capturing the public imagination, making it easier to raise support. There may already be existing value by the public as well, as many communities have historical connections to seafaring or fishing heritage and a longstanding relationship with the sea (Claesson 2011; Firth 2015).

However, there are unique challenges relating to capacity development for maritime capacity development in contrast to those faced on land. These are important to understand when considering the gap between maritime and terrestrial initiatives as they provide insight into motivations and limitations within the context of maritime cultural heritage. First, the field of maritime archaeology, and especially underwater archaeology, is still relatively young compared to terrestrial archaeology. There simply is not the same pool of knowledge, resources, expertise and infrastructure to dip into when carrying out new capacity development initiatives (Bass 2012). This is compounded by its multidisciplinary nature—a variety of expertise in different fields is required for many projects developing capacity in relation to heritage connected to the sea. Second, the legal frameworks in place for the protection of maritime cultural heritage are less well formed. The UNESCO 2001 Convention on the Protection of the Underwater Cultural Heritage only entered into force in 2009 and as of 2018 has been ratified by 60 out of 193 UN member states. It explicitly lists building capacity through training and information sharing and raising public awareness within its larger protections for underwater cultural heritage (Maarleveld et al. 2013). In previously existing international law, maritime and marine cultural heritage was often an afterthought. National laws traditionally focused on regulating salvage privileges and military ownership (Bowens et al. 2009). Third, underwater treasure hunting and salvage, often thinly veiled as commercial archaeology operations, are still operating and publically acceptable (Pringle 2013). Commercially exploitative operations frequently displace legitimate archaeological research and capacity development (Duarte 2012). Finally, maritime cultural heritage projects have many considerations. Offshore projects are expensive to run and regularly require special technology. Diving and intertidal projects have safety concerns. In certain regions, many shipwrecks are connected with loss of life or military gravesites that require careful treatment. Training initiatives for capacity development must take all these into consideration and ensure that adequate funding and planning is available (Flatman 2009).

These are substantial challenges to address. To achieve a deeper and more comprehensive understanding of capacity development and contribute to its overall improvement, a model for initiative evaluation and analysis is suggested.

The Parameter Model

In order to gain a more structured understanding of capacity development for the effective implementation and evaluation of initiatives, a framework for categorizing and organizing the multitude of existing initiatives is needed. This paper proposes a model for classifying capacity development initiatives for cultural heritage under threat by ten parameters: Heritage Type, Funders, Drivers, Funding Structure, Funding Stream, Levels, Location, Target, Approach, and Time Frame. Descriptions of the categories under each parameter and their relationships with one another follow. The parameter model developed by the authors, is based on an extensive review of current and recent capacity development initiatives and literature on capacity development with respect to threatened cultural heritage, including amongst others Perini and Cunliffe (2014). It is not a rigid model, rather it is a working model that can be adapted when needed and in response to changes in practices within the field.

Parameters

Heritage Type

A capacity development initiative can focus on tangible cultural heritage, intangible cultural heritage, thematic cultural heritage, or all cultural heritage. Thematic cultural heritage is heritage falling within a specific category, such as maritime heritage or Jewish heritage. Heritage type identified may depend on the Drivers of the initiative being undertaken or on the Funders involved. Certain funders specialize in specific types of heritage (e.g. the Honor Frost Foundation only focuses on maritime cultural heritage).

Funders

Funders are the stakeholders on the donor side providing the monetary investment and impetus. Funders are motivated by Drivers, but can sometimes be the Driver as well as the Funder: i.e. Funder is proactive in targeting certain projects to fund or even develop specific projects within the funding agency. The ten main categories of funder are as follows:

UN Agencies and advisory bodies and partners: any UN and related intergovernmental organization (e.g. UNESCO [UN Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization] and ICCROM [International Centre for the Study of the Preservation and Restoration of Cultural Property]).

Associations of states: any union of nations which includes cultural heritage protection and sustainable development among its activities (e.g. the European Union).

International financial institutions: any multilateral development banks and regional financial institutions funding sustainable development, tourism, or cultural heritage related programs (e.g. the World Bank).

Government-direct: any funding directly from a national government agency or department (e.g. USAID [United States Agency for International Development]).

Government indirect: any funding not directly provided by a national government but instead through a secondary means such as a fund, organization, trust, or museum (e.g. the British Council, Cultural Protection Fund).

Non-governmental organizations: any funding from government independent organizations as defined by the UN (e.g. Centre for International Heritage Activities).

Universities: any department, center, or consortium (e.g. University of Oxford, Endangered Archaeology in the Middle East and North Africa; University of Southampton, Maritime Archaeological Survey of Oman).

Museums: any museum (independent, public–private, government subsidized or funded) or museum institution (e.g. British Museum, Getty Conservation Institute).

Non-profits and charities: any non-profits and charities whose mission encompasses cultural heritage (e.g. Arcadia Fund, Global Heritage Fund).

Private: any for-profit or privately held firm or fund (various).

Drivers

Drivers are the motivating forces behind Funders and funding. An initiative may be stimulated by one or more Drivers. Certain Funders and Drivers are linked. Among the primary drivers are international aid and development goals, government or UN agency/advisory body/partners mandate, special projects and initiatives, organizational missions, academic and research motivations, and initiatives that react to an emergency or catastrophic event. International aid and development goals drive initiatives by funders who have economic and socially set development goals to achieve. These include UN agencies/advisory bodies/partners, associations of states, international financial institutions, and governments. Government or UN agency/advisory body/partner mandates are a driver for initiatives funded by UN agencies/advisory bodies/partners, governments, and associations of states who are legally or constitutionally obligated to pursue goals related to cultural heritage. Special projects and initiatives are Drivers for when initiatives are funded as part of a special fixed term allocation of grants (see Funding Stream: temporary projects and special projects). An organizational mission also falls under Drivers for initiatives funded by NGOs, non-profits and charities, museums, and private sources, who have a mission statement or specific goals relating towards cultural heritage. Most NGOs, non-profits, etc. working in this field are driven by organizational missions. Academic and research motivated drivers can apply to most categories of funders, although it is most commonly a driver for initiatives funded by universities and museums. It encompasses any initiatives where the purpose of safeguarding cultural heritage is born out of intellectual desire. Finally, reaction to an emergency or catastrophic event is a Driver for any funding generated after an event where funders are motivated to action. War, acts of terrorism, and natural disasters are the most common examples of emergency and catastrophic events that push funding.

Funding Structure

The Funding Structure describes how the initiative is funded based on the category of Funders and number of Funders providing the funding. There are two main Funders categories for threatened cultural heritage (although there is nuance within these categories): cultural heritage focused, and mixed focus. A cultural heritage focused funder is one whose activities are exclusively concentrated within the cultural heritage sphere. A mixed focus funder is one whose activities include, but are not limited to, the cultural heritage sphere.

Funding Stream

A Funding Stream is how the Funders allocate funding to initiatives. It is affected by Funding Structure and b. There are three main funding streams: single initiative funding, on-going funding rounds, and temporary projects and special programs. Single initiative funding is when grants are given as one-time allocation to a one-off initiative. On-going funding rounds are when a funder or group of funders regularly provide grants for projects/initiatives. Temporary projects and special programs funding is when funding comes through grants associated with a fixed-term and often thematic round of allocations.

Levels

There are three Levels at which capacity can be developed: individual, institutional, and societal. Initiatives can develop capacity at a single level, or at all three (UNDP 2008, 2009; OECD 2006; Fukuda-Parr et al. 2002). Capacity at the individual level involves a person gaining knowledge or skills. At the institutional level it entails a group, network, or team of individuals gaining knowledge and skills sufficiently to develop the working ability of an entire institution or institutions. Societal capacity involves a cultural shift. Often this is more value based, such as awareness, public opinion, and youth engagement (British Council 2018).

Location

The Location is the geographical scope of the initiative. Capacity can be developed for a site, country, group of countries or region, or multiple regions. The smaller the location of the initiative, the more focused it can be in its Targets. Capacity development for a country takes place across the country or aims to impact the whole country. Initiatives for a group of countries or region are often in reaction to a regional threat or address a common theme across similar countries. Multi-regional capacity development occurs in response to threats that cross regional borders. Location and Level can be, but are not necessarily, interrelated. It is unlikely for a multi-regional initiative to develop capacity at an individual level. However, a national initiative is likely to develop capacity at individual and institutional levels.

Target

A Target is the desired outcome of the Approach. The main targets identified are awareness and value, knowledge (expertise vs. skill), partnership and collaboration, community engagement, leadership, technological development, and economic development. Targets can be hard or soft, for example technological development as opposed to leadership. An initiative whose target is awareness and value is aiming to raise awareness and change public perceptions of cultural heritage in order to safeguard it. Knowledge targeting initiatives encompasses two forms: those that teach skills (concrete task-based practices) and those that build expertise (theoretical thought-based learning). When partnership and collaboration are the target, the initiative is trying to either strengthen existing networks or forge new connections that better enable cultural heritage to be served. Community engagement targeting initiatives attempt to get the community involved in the protection of threatened heritage. This could take place within the context of tourism, archaeology field work, or monitoring, among others. Targeting leadership means that the initiative is fostering not only skills and expertise but attempting to instill an ethos of leadership. Nurturing leaders increases the likelihood that an initiative will result in self-directed and long-lasting sustainable change. Initiatives targeting technological development are attempting to increase technologically related capacity and harness this towards monitoring, inventory, documentation, and other relevant projects. Economic development targeting initiatives aim to protect cultural heritage by spurring economic growth and impacting socioeconomic conditions in order to affect how people interact with and relate to cultural heritage. A Target does not correspond to an Approach, although certain initiatives are interlinked (network creation and partnership and collaboration). An Approach can have more than one Target(s), and the same targets can be achieved through different approaches. The Target(s) will depend on the Heritage Type, Funders, and Drivers.

Approach

The Approach is how the capacity development initiative is carried out; what method or methods are being used in order to hit a Target(s). Common approaches include: assessment and inventory, emergency action and planning, in-country/in-region training, out-of-country training, education, sustainable tourism creation, and network creation. Assessment and inventory aim to build capacity by gathering and compiling sharable information. This can take many forms, from on-the-ground baseline surveying to tech-based investigations from afar. Emergency action and planning initiatives are in place for situations where a natural or human disaster event may happen, and develop capacity through advanced preparation planning and/or urgent response actions. In-country or in-region training develops capacity by bringing stakeholders together within their own country or region. This is in contrast with out-of-country training, which brings stakeholders together in a different place. This may be for reasons relating to access to resources and expertise, safety of participants, and/or financial reasons. The education approach focuses on developing capacity through the use of educational institutions, usually tertiary ones. The sustainable tourism approach’s objective is to foster the protection and conservation of cultural heritage through the creation of tourism around a site or area. This can be achieved by working with professionals in the heritage field, or by engaging the local community in the creation of the tourism site. Network creation develops capacity by bringing people or institutions together to forge collaborations, exchange dialogue, and share expertise. This can take place between experts in a field or disparate groups (for example a governmental department and an NGO). More than one approach can be used, and there can be variation in how exactly they are applied. The Funders and Drivers will determine which are used.

Time Frame

Time frames for initiatives operate along a continuum but can be divided into short term, medium term, and long term. Short term initiatives take place over a few days or weeks. These include individual workshops, trainings, conferences, and projects. Medium term initiatives take place over several months to a year. Examples would be trainings with multiple sessions (in-country and out-of-country). Long term initiatives take place over multiple years. These could be a reoccurring series of workshops or conferences, the establishment of a collaborative (private–public) partnership, or granting of a series of scholarships. The Time Frame is influenced by many other parameters: Approach, Funders, Funding Steam, and Drivers.

The parameter model will now be applied to a series of case studies, each featuring a capacity development initiative for threatened cultural heritage, in order to begin to evaluate the effectiveness of this approach.

Case Studies

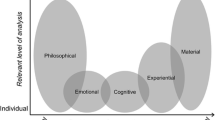

Two case studies of maritime capacity development initiatives that explore cultural heritage in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region are presented in order to explore how this model might be applied. They are the Honor Frost Foundation Scholarship and Bursaries, and the Maritime Archaeology Survey of Oman (MASO). The case studies were selected from a larger number of initiatives originally examined as part of the research for this paper. Each case study includes a brief description of the initiative and its results based on self-reported outcomes. The case studies are then examined using the parameters outlined in the previous section (not necessarily in the same order as outlined in Fig. 1).

Honor Frost Foundation Scholarships and Bursaries

The Honor Frost Foundation (HFF) was founded in 2011 to “promote the advancement and research, including publication, of maritime archaeology with particular but not exclusive focus on the eastern Mediterranean with an emphasis on Lebanon, Syria, and Cyprus” (Honor Frost Foundation n.d.). Amongst other funding initiatives, scholarship and bursaries offered by the Honor Frost Foundation aim to develop capacity in the targeted countries by funding Masters, Doctoral, and Post-Doctoral study at international institutions (in UK, Europe, Australia, and the eastern Mediterranean) for Cypriot, Lebanese, Syrian, and Egyptian nationals (Honor Frost Foundation n.d.).

The initiative is notable in that it is possible to see concrete short-term results. However, the actual impact of this initiative depends on how the graduates apply their knowledge, and whether their efforts successfully help develop capacity. This would need to be examined over the long-term. Over 20 scholarships and multiple bursaries have been awarded since the Foundation was established in 2011 (Honor Frost Foundation n.d.). This has built up capacity in the target countries by increasing the pool of people with high level skills and expertise available to work (or currently working) in those countries. It has expanded the scope of the heritage field in the target countries, as each scholar also adds their own research to the overall body of knowledge. The bursaries have allowed for network creation by bringing recipients into contact with the larger archaeological community and creating opportunities for future international collaboration. Longer-term results and effects on the capacity of the target countries will be revealed in the future (see Table 1).

The Maritime Archaeological Survey of Oman

The Maritime Archaeological Survey of Oman (MASO) was commissioned in 2014 as a joint initiative between the Oman Ministry of Heritage and Culture and an executive management team consisting primarily of the Maritime Archaeological Stewardship Trust (MAST), the University of Southampton, and the Western Australian Maritime Museum’s Department of Maritime Archaeology. The aim of MASO was to “further extend capacity to identify and manage the maritime archaeological resource of Oman” and “to develop a comprehensive holistic approach to maritime heritage management” (Blue et al. forthcoming).

MASO developed capacity for a wide range of stakeholders across several levels and sectors. Training and workshops were carried out for “the Ministry of Heritage and Culture (MHC) staff, academics, other ministries, developers, fisherman, professional and recreational divers” with the aim of increasing skills and expertise (Blue et al. forthcoming). Specific training was afforded to the staff of the MHC’s maritime division both in the classroom and importantly in the field, on targeted Environmental Impact Assessment surveys in advance of coastal development. Institutional capacity was further increased through the production of the desktop assessment, which was “the first comprehensive repository of digitally related data concerning coastal and underwater sites” in the country (Blue et al. forthcoming). It is notable for its focus on incorporating capacity building in all aspects of the project (see Table 2).

Towards a Deeper Understanding of Capacity Development

The case studies aim to serve two purposes. The main purpose is to function as a canvas for the application of the parameter model in order to evaluate it as an operational framework for assessing capacity development initiatives for threatened cultural heritage. The case studies demonstrate how the parameter framework can be applied to analyze initiatives by applying consistent categorizes, and what conclusions can be drawn from this approach. A secondary purpose is to provide a deeper, more granular, assessment of how exactly individual capacity development initiatives for the protection and conservation of threatened cultural heritage function. However, there is no scope to explore the specific attributes of these case studies within the context of the volume. But suffice to say a few themes could be further developed from the case studies and other initiatives examined:

Engaging local communities and generating input from local stakeholders.

Creating value and changing priorities.

Integrating maritime cultural heritage into already existing capacity development initiatives for (1) general threatened cultural heritage (2) other types of capacity development.

Considering both short-term and long-term impact and development for self-sufficient, sustainable initiatives.

Incorporating technology (distance learning, software skills, incorporation of satellite and remote imaging technology, open-source sharing, etc.).

Involving experts from a range of related fields.

By applying a framework such as the parameter model, patterns and conclusions can begin to be drawn about what makes an initiative effective and what themes are key for successful initiatives. This information enables the creation and implementation of better designed and more effective initiatives.

Analysis of Parameter Model and Applications for Improving Capacity Development

As previously stated, the main purpose of the case studies was to demonstrate and subsequently evaluate the parameter framework as a tool to better understand and therefore improve capacity development for threatened cultural heritage, specifically maritime and coastal heritage. An evaluation of how the parameter model assesses capacity development for threatened cultural heritage in general follows.

Consistent Model for Comparison of Initiatives

The parameter model establishes a consistent framework for assessing and comparing initiatives. The same framework can be used to evaluate a wide range of capacity development initiatives. Initiatives focused on different types of heritage, including different funders, from government (MASO), to government funded initiatives, NGOs and charities (HFF), as well as different approaches (for example in-country training to, educational (HFF) and network creation (Endangered Archaeology in the Middle East and North Africa [EAMENA]; this project recently extended to the maritime zone (MarEAMENA) (Bewley 2018). The framework can also be applied across different time frames and locations. A consistent model allows for a series of initiatives to be classified and then sorted or compared by parameter. The case studies could be grouped and assessed by target or a funding structure (all initiatives which target partnership and collaboration, for example). This consolidation may aid heritage professionals and others interested in developing capacity for threatened cultural heritage, in order to better evaluate existing initiatives. It can also help in establishing new initiatives based on lessons learned from this evaluation process.

Understanding of Funders and Drivers

Who funds and what drives the funding of a project are two of the most critical factors in understanding how capacity development initiatives operate. By classifying these factors within a framework, it becomes simpler to assess the functionality of an initiative. As a result of this research, the authors were able to identify governments as a critical funder. The funding can be a mixture of direct and indirect government funding. Initiatives can also have multiple funders, with governments as just one of many funders, while others had only a single government funder. In terms of drivers, a funder was most often motivated by its organizational mission/mandate/development goal (e.g. HFF’s commitment to education) but also sometimes by external factors, such as “Reaction to an emergency/catastrophic event” or “Academic and research motivated”. This could have implications for those seeking funding in the future; it can suggest which avenues for funding are the most promising. It may also assist in providing guidance to larger funders as to what kind of initiatives they could support.

Examination of Integration of Local Stakeholders

The integration and involvement of local communities is crucial for sustainable capacity development to occur (British Council 2017; ICCROM 2015; Rising from the Depths 2018; Sharfman 2017). Classification by the parameter model facilitates the examination of if, where, and how local stakeholders are involved in the initiative. Does the initiative target local stakeholders for community engagement, leadership, or economic development purposes? Does the approach work with local communities though educational efforts, in-country trainings, or sustainable tourism development? Are any local stakeholders funders? In the context of the case studies, the MASO is a good example of an initiative that integrated local stakeholders throughout. The Ministry of Heritage and Culture of the Sultanate of Oman was a locally based funder but also a beneficiary. This allowed it to have control over exactly what capacity was needed. The key target of the MASO project was extending knowledge and this was achieved through three key approaches: assessment and inventory, in-country training, and educational. These approaches hoped to address national needs and were explicitly aimed to develop capacity at the societal level. This included education for students (educational approach) and training and awareness-raising for developers (in-country training) that extended beyond simply training the Ministries.

The parameters can be compared to the outcomes of the initiative to imply effective strategies. For example, is an educational approach or a sustainable tourism development approach, more conducive to the sustained development of societal capacity? As is also apparent from analysis of the model, this poses many questions for further research, while also recognizing that initiatives can vary quite considerably.

Investigation of Gaps in Efforts

The parameter model allows capacity development initiatives to be classified in order to identify gaps in capacity development efforts across a series of programs. This enables the identification of gaps in targets and in the heritage types addressed, among other shortcomings, rather than just presenting a basic evaluation based on which country does not have sufficient initiatives, or what threat is being addressed. It could also suggest that more nuanced and harder to quantify targets and aspects of capacity development are being neglected. These are important for creating value. Once gaps are identified, ideas for future initiatives can be presented.

Identification of Themes and Structure

Classification of parameters aids in the identification of themes and structures relevant for analyzing initiatives. Themes and trends can be identified in the case studies and overall research. These include developing capacity at the individual and institutional levels, and the dominance of “knowledge” and “partnership and collaboration” as targets. Identifying themes can provide information about the nature of capacity development in a region, or across a series of initiatives. The underlying structure of initiatives can be identified as well. For example, many successful initiatives employ multi-year time frames. This does not mean that capacity can only successfully be developed continuously over several years; active capacity development may take place for only a fraction of that time. The short-term actions and sub-projects (a smaller project that forms part of the initiative using one or more approaches concurrently or separately) that make up the larger initiatives, can last for as little as months or even days. The HFF Scholarships and Bursaries scheme is an example of an initiative that continuously develops capacity, as it has students placed at universities year-round. Identifying the structure can lead to conclusions for effective evaluation. For example, for an initiative that has short-term sub-projects, it is necessary to evaluate the results of both the sub-projects and the overall initiative to gain a complete overview of whether capacity was successfully developed.

Critique of Parameter Model

The parameter model has a number of strengths. It is adaptable and can be modified for application to different types of capacity development. It is also holistic, presenting a comprehensive framework that addresses all aspects of an initiative from funding to time frame. Additionally, the model is simple to understand and straightforward to use. The parameter model also has shortcomings. It currently largely addresses threatened cultural heritage, so cannot be applied outside of this field without alteration. It is funder focused, and does not factor in exactly which types of stakeholders are involved (beyond level of capacity targeted) in receiving capacity, and how this may affect the implementation and outcomes of initiatives. The model also may not capture all of the nuance of certain initiatives. Overall the parameter model should be considered a working model, open to change based on criticism and feedback.

Conclusion

Frameworks, like the parameter model, can be used to look at an initiative or a series of initiatives in a deeper, more meaningful, and structured way. Both qualitative evaluation and quantitative analysis are possible. By combining lessons learned from a deep review of individual case study initiatives, and conclusions drawn from the examination and evaluation of the case study initiatives using the parameter model framework, a greater understanding of capacity development can be achieved. This results in an improvement in capacity development for cultural heritage under threat as it leads to more informed decisions for the creation and effective implementation of future initiatives, allows for more organized and standardized evaluation of previous and ongoing initiatives (including modifications to ensure sustainable success), and helps direct where research and funding related to capacity development should focus attention. This improvement in capacity development for cultural heritage under threat extends to maritime cultural heritage initiatives. Improving capacity development for maritime cultural heritage under threat is an important step in closing the gap between efforts for the protection and safeguarding of terrestrial and maritime heritage under threat, and protecting maritime cultural heritage for the future.

References

This bibliography is not exhaustive. Further references were used by the authors but space is limited.

Bass G (2012) The development of maritime archaeology. In: Ford B, Hamilton D, Catsambis A (eds) The Oxford handbook of maritime archaeology. Oxford University Press Oxford Handbooks Online, Oxford. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199336005.013.0000. Accessed Sept 2019

Bewley R (2018) Endangered archaeology in the Middle East and North Africa, Getty Conservation Institute Conservation Perspectives, Spring 2018. http://www.getty.edu/conservation/publications_resources/newsletters/33_1/endangered_archaeology.html. Accessed Sept 2019

Blue L, Vosmer T, Green J (forthcoming) The maritime archaeological survey of Oman. In: Rodrigues J, Traviglia A (eds) Shared heritage: proceedings from the sixth international congress for underwater archaeology (IKUWA6), 28 November–2 December 2016. Western Australian Museum, Fremantle. Archaeopress, Oxford 2019

Bowens A et al (eds) (2009) Underwater archaeology: the NAS guide to principles & practice. Wiley: Blackwell, Hoboken

British Council (2017) In harm’s way: aspects of cultural heritage protection. British Council, London

British Council (2018) Cultural heritage for inclusive growth. British Council, London

Capacity Development Group, Bureau for Development Policy (2010) Measuring capacity. United Nations Development Programme, New York

Claesson S (2011) The value and valuation of maritime cultural heritage. Int J Cult Prop 18:61–80

Duarte RT (2012) Maritime history in Mozambique and East Africa: the urgent need for the proper study and preservation of endangered underwater cultural heritage. J Marit Archaeol 7:63–86

Europe Aid (2005) Institutional assessment and capacity development: why, what, and how?. European Commission, Italy

Firth A (2015) The social and economic benefits of marine and maritime cultural heritage: towards greater accessibility and effective management. Fjordr Limited for Honor Frost Foundation. ISBN 978-0-9933832-0-5

Flatman J (2009) Conserving marine cultural heritage: threats, risks and future priorities. Conserv Manag Archaeol Sites 11:5–8

Fukuda-Parr S, Lopes C, Malik K (2002) Capacity for development: new solutions to old problems. United Nations Development Programme, New York

Honor Frost Foundation (n.d.) https://honorfrostfoundation.org/the-foundation/. Accessed Sept 2019

ICCROM (2015) People-centered approaches to the conservation of cultural heritage: living heritage. ICCROM, Rome

ICCROM (n.d.) Protecting cultural heritage in times of conflict contributions from the participants of the international course on first aid to cultural heritage in times of conflict, vol 3. ICCROM, Rome

ICOMOS (2006) Underwater cultural heritage at risk: managing natural and human impacts. Heritage at risk special edition. ICOMOS, Paris

Maarleveld T, Guérin U, Egger B (2013) Manual for activities directed at underwater cultural heritage: guidelines to the annex of the UNESCO 2001 convention. UNESCO, Paris

Machat C, Petzet M, Ziesemer J (eds) (2014) Heritage at risk: world report 2011–2013 on monuments and sites in danger. ICOMOS, Berlin

Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (2006) The challenge of capacity development: working towards good practice. OECD, Paris

Perini S, Cunliffe E (2014) Towards a protection of the Syrian cultural heritage: a summary of the international responses, vol II. Heritage for Peace, Girona

Pringle H (2013) Troubled waters for ancient shipwrecks. Science 340:802–807

Redford D (2014) The Royal Navy, sea-blindness and British national identity. In: Maritime history and identity: the sea and culture in the modern world. IB Tauris, pp 61–78

Rising from the Depths (2018) Funding: marine coastal heritage. Rising from the depth GCRF. https://risingfromthedepths.com/marine-cultural-heritage/. Accessed Sept 2019

Sharfman J (2017) Troubled waters: developing a new approach to maritime and underwater cultural heritage management in sub-Saharan Africa. Leiden University Press, Leiden

United Nations Development Programme (2008) Capacity development practice note. United Nations Development Programme, New York

United Nations Development Programme (2009) Capacity development: a UNDP aaPrimer. United Nations Development Programme, New York

United Nations Development Programme (n.d.) Supporting capacity development: the UNDP approach. United Nations Development Programme, New York

USAID (n.d.) Organizational capacity development measurement. USAID, Washington, DC

World Bank Institute (2009) The capacity development results framework: a strategic and results-oriented approach to learning for capacity development. The World Bank

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Recinos, K., Blue, L. Improving Capacity Development for Threatened Maritime and Marine Cultural Heritage Through the Evaluation of a Parameter Framework. J Mari Arch 14, 409–427 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11457-019-09246-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11457-019-09246-9