Abstract

The present study examines the phenomenon of compensative and compulsive buying in a developing consumer society such as Poland. Firstly, the obtained empirical data make it possible to estimate the prevalence of compensative and compulsive buying among Poles married or in stable relationships. Secondly, the conducted analysis shows to what extent the prevalence is differentiated by individual (self-esteem), cultural (materialism), and sociodemographic conditions (gender, age). The findings come from a survey conducted in 2017 based on a nationwide statistically representative sample of 1,121 Poles married or in a stable relationship aged 18 years old and over. Drawing on this survey based on the German Compulsive Buying Indicator (GCBI), the prevalence of compulsive buying is observed at about 3%. Like in other countries, it turns out that gender, age, self-esteem, and materialism differentiate the extent of susceptibility to compensative and compulsive buying in Poland, too. The direction of the correlations is coherent with the findings in other countries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Disorders connected with buying were noticed for the first time by Kraepelin (1909) and then by Bleuler (1934), who used the term of “buying maniacs” as an equivalent of Kraepelin’s “oniomaniacs.” The studies referring to the disorder were not continued until the end of 1980, when the study by Faber et al. (1987) triggered a broader discussion about the phenomenon. Since then, studies on compulsive buying have been conducted in two different areas, those based on clinical psychology and psychiatry and those within the frame of consumer research, which is the reference point for this paper. The latter treat compulsive buying as an irrational way of purchasing, and they focus on the recognition of demographic and sociocultural factors of compulsive buying. Studies by clinical psychologists and psychiatrists describe compulsive buying either as a behavioural addiction or as a disorder of impulse control (Müller et al. 2015).

O’Guinn and Faber (1989, p. 149) define compulsive buying as “chronic, repetitive purchasing that occurs as a response to negative events or feelings.” Although the purchasing act is positively experienced by compulsive buyers as a peculiar compensation for failures or an escape from the reality of everyday life, the long-term consequences of compulsive buying are psychologically (feelings of guilt, weak self-esteem), socially (disordered interpersonal relationships), and economically (debts) negative (O’Guinn and Faber 1989). Even the individual’s growing consciousness of these negative consequences is not a sufficient protection against such activities (Kearney and Stevens 2012).

Conceptual Framework

Terminological Content of Compulsive Buying

While treating compulsive buying as an impulse control disorder, it is assumed that persons suffering from the disorder are not able to control impulses, and they exhibit this behaviour in spite of the negative consequences for them or others. This behaviour is preceded by the stage of increased tension or anxiety which can be replaced by experiencing pleasure, satisfaction, or relaxation only as a result of this particular behaviour. Defining compulsive buying as an obsessive-compulsive disorder, it is assumed that a compulsive buyer experiences internal pressure to realize this behaviour, which leads to a reduction of unpleasant feelings. The repetition of the behaviour bases on routine – without any special concern about its sense (Thalemann 2009).

Müller et al. (2015) describe the phenomenon as an over-average concentration on purchasing manifested in a desire to buy which is difficult to hold back. The feeling of pleasure and relief are intrinsically related to the buying act, and it is replaced by the feeling of guilt and remorse. The activity of compulsive buyers is limited to the purchasing process; the actual use of the acquired goods recedes into the background; quite often they remain hidden and unpacked at home. The purchase is a way of increasing one’s own value or a form of reaction to the experienced negative mood. This over-average concentration on shopping can be a result of individuals’ difficulties in defining themselves, which leads to the consideration of different substitutes for identity deficiencies. Compulsive buying might be an alternative (Claes et al. 2018).

When compulsive buying is treated as a type of irrational purchasing, the explanation takes another course. According to Antonides and van Raaij (1998), the term “consumer behaviour” embraces mental and physical acts including their meanings, motives, and causes characterizing individuals and social groups. On the one hand, consumer behaviour is a direct observable action like buying something. On the other, consumer behaviour is a set of different meanings, senses, and motivations which are hidden, but they actually guide consumer behaviours. Whether a purchasing act can be treated as rational or irrational depends on its invisible dimension. From the post-modern paradigm, each consumer constructs their own rationality. In this sense, compulsive buying could be assessed as rational because it yields a special kind of profit for compulsive buyers, namely, release of tension. Some researchers point out that compulsive buyers use the symbolic values of products to enhance their social status, which seems to be quite rational (Harnish et al. 2018).

To differentiate between rational and irrational consumer behaviour, the application of rational choice theory could be helpful. Consumers choose this behaviour from a set of the accessible options which maximizes profits or minimalizes the incurred costs (Becker 1976). In this sense, compulsive buying is irrational because costs of the behaviour are higher than profits. Although a compulsive buyer experiences a desirable relief of tension and an improved self-esteem (profits), the potential negative consequences (costs) are much more complex – turning back remorse and feelings of guilt, loss of self-control to a greater or lesser extent, withdrawal symptoms, excessive expenditures and debts of the household, crisis of interpersonal relationships, interrupted professional career, comorbidity of behavioural or substance addiction, or even problems with the law (Achtziger et al. 2015). An individual’s view about profits and costs of a behaviour is conditioned not only by the individual’s psychological traits but also by sociocultural features of their social environment.

Compulsive and compensative buying are strictly connected. On the one hand, compensative buying is an indicator of compulsive buying. Assuming the latter is an addiction to shopping, the experience of compensation delivered by a purchase constitutes the object of the addiction. In this sense, compulsive buyers always purchase compensatively. On the other hand, compensative buying is an autonomous purchase style which may precede the stage of compulsive buying (Faber and O’Guinn 1992). This idea is reflected in the compulsive buying scale distinguishing three basic segments of shoppers placed on the continuum: ordinary, compensative, and compulsive buyers (O’Guinn and Faber 1989). Compensative, like compulsive buying does not primarily aim to make use of the functional utility advantages of a given item but to compensate the problems occurring in quite different life areas. Compensative buyers experience satisfaction based on a purchasing act, which is able to reduce internal tension and to strengthen their self-esteem (Scherhorn et al. 2001). In spite of the similarity, compensative buying does not equal compulsive buying. Compensative buying serves instrumentally to compensate for the failures, but the costs of the compensation never exceed the profits, whereas this balance is disturbed in case of compulsive buying. Without doubts, the transformation point from compensative to compulsive buying is difficult to specify. Compulsive buying can be expected if the buyers, for example, consider the behaviour as a reward and lose control of their behaviour repeatedly as for the duration time, frequency, or intensity (Thalemann 2009).

Prevalence

Most studies conducted on statistically representative samples evidence the prevalence of compulsive buying on the level under 10% (Maraz et al. 2016). For example, a nationwide study conducted in Germany in 2001 showed the share of compulsive buyers on the level of 8% (Neuner et al. 2005). The data obtained in 2010 in Denmark evidenced 6% versus 10% of compulsive and compensative buyers among 15–84 years old (Reisch et al. 2011). At the same time, in Austria, the shares were observed on the levels of 8% and 19% (Kollmann and Unger 2010). A study conducted in 2004 in the United States of America (USA) displayed a 6% prevalence of compulsive buying among adults (Koran et al. 2006). The share of compulsive buyers in Great Britain was found to be 13% (Dittmar 2005).

In Spain, a clear tendency for compulsive buying was found in 7% of respondents aged 15–65 (Otero-López and Villardefrancos Pol 2015). An online survey conducted in Estonia displayed an 8% share of compulsive buyers (Raudsepp and Parts 2014). The results from Hungary evidenced the segment of compulsive buyers embracing 2% of the general population aged 18–64 (Maraz et al. 2015a). The share of compulsive buyers among the customers visiting some Hungarian shopping centres was nearly 9% (Maraz et al. 2015b).

Research Aim

The goal of the presented studies was an attempt to answer the following research questions:

-

1)

Does anything like compulsive buying exist in Poland?

-

2)

To what extent do the selected demographic, individual, and societal variables differentiate susceptibility to compulsive and compensative buying?

-

3)

To what degree will the findings differ from the results obtained in other countries?

The phenomenon of compensative and compulsive buying accompanies the development of consumer society, although susceptibility to the behaviours varies depending on sociodemographic and sociocultural conditions to a different extent (Fässler 1997). On the one hand, the development of consumer society in different countries has a universal character resulting in similar correlations between compensative/compulsive buying and demographic, individual, or societal factors. On the other hand, the strength of the correlations should be different due to various sociocultural conditions. The more different the conditions in particular societies, the bigger differences concerning susceptibility to compensative and compulsive buying should appear. For this reason, a similar share of compulsive buyers in Poland and in other European countries or the USA is expected, although the result should be placed in the lower part of the most often reported interval of the compulsive buyers’ rate (2–8%). At the same time, the social factors influencing susceptibility to compensative and compulsive buying should be similar to other European countries and the USA.

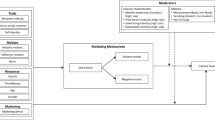

Research results from different countries make it possible to justify the above assumptions. The data obtained until now show that gender, age, self-esteem, and materialism considerably differentiate susceptibility to compensative and compulsive buying. Most studies pointed to a stronger susceptibility of women to compulsive buying than of men. This pattern is confirmed by studies conducted in Germany (Neuner et al. 2005), Denmark (Reisch et al. 2011), Austria (Kollmann and Unger 2010), Spanish Galicia (Otero-López and Villardefrancos Pol 2015), or in Hungary (Maraz et al. 2015a) as well as studies among adolescent consumers in Canada (d’Astous et al. 1990), Germany, South Korea, and Poland (Lange et al. 2005). Some results deny the existence of splitting in reference to gender. For instance, studies conducted in 2004 in the USA pointed out that the percentage of women and men displaying susceptibility to compulsive buying is approximately the same (6% vs. 5.5%) (Koran et al. 2006). Italian researchers drew similar conclusions based on studies among youth and young adults aged 13–20 (Villella et al. 2011).

If a stronger susceptibility to compulsive buying in women is reported, the explanation of the result takes at least three directions. Firstly, the specific character of women’s socialization process is mentioned which supports the progress of more passive and emotional ways to manage stress and conflicts. They have susceptibility to solving problems without ostentation and basing on legal solutions. One way is shopping, which is not only accepted in the consumer society but it is even desirable as a source of social prestige. In addition, in traditionally oriented societies, the differentiated socialization between female and male roles is the cause why women are more prepared to look after the household. Hence, purchasing and deriving pleasure from shopping are socially perceived as more “natural” for women. This is the reason why women’s susceptibility to compulsive buying may be greater and compulsive buying can be practised unnoticeably even until financial troubles of the household appear (Scherhorn et al. 1990).

Dittmar (2005) emphasized that buying for women is a more enjoyable activity than for men. It means shopping can cause more positive feelings among women than among men to whom shopping is a chore more often, while more positive attitudes towards shopping strengthen susceptibility to compensative or compulsive buying. In part, the differences between men and women might be a result of the gender’s psychological conditions. Women reveal their shopping habits and connected with them emotional states more willingly than men (Black 2011).

Taking into account the above explanations, a greater susceptibility to compensative and compulsive buying among Polish women than among men is to be expected (Hypothesis 1). Still, the Polish society is more traditionally oriented in the area of female and male social roles than other European countries or the USA. For example, only 13.4% of Poles strongly disagree with the statement that men make better business executives than women, while the same opinion is represented by 32.1% of Germans, 32.8% of US-Americans, 33.2% of the Dutch, and even 47.6% of Swedes. While 20.5% of Poles strongly disagree with the view that university education is more important for a boy than for a girl, the results for other countries are twice or even threefold higher (the USA 41.7%, Netherlands 43.6%, Germany 44.8%, Sweden 56.2%) (WVS 2012).

Apart from gender, researchers observed a stronger susceptibility to compulsive buying among younger people than among the elderly. According to Dittmar (2005), compulsive buyers are younger than ordinary buyers by 8–11 years, on average. This conclusion was confirmed in 2004 by the US researchers who pointed out the average difference of nine years between compulsive buyers and other types of buyers (Koran et al. 2006). Similar correlations were found by Italian researchers who observed the share of compulsive buyers in the population aged 18–20 on the level of 6.3%, whereas the rate amounted to 14.5% among the youth aged 13–17 (Villella et al. 2011). This pattern was reflected in the research results collected in Spanish Galicia (Otero-López and Villardefrancos Pol 2015), Germany (Neuner et al. 2005), Austria (Kollmann and Unger 2010), and in Denmark (Reisch et al. 2011).

Without doubts, conspicuous consumption closely connected with the materialistic orientation plays an important role in the life of young people. During the further life phases, the tendency for conspicuous consumption becomes weaker leading to a poorer susceptibility to compulsive or compensative buying, while youth and young adults value material objects and find their possession a desirable source of personal happiness. This attitude towards materialistic values connected with easier availability of loans leads to the development of compensative and compulsive buying among young generations (Benson et al. 2010). In addition, consumer industry creating a symbolic value of brands supports this positive attitude towards consumption/possession of goods, which is convincing particularly for young people. The symbolic value of brands is used by consumers to demonstrate the real or expected social status, to confirm their own social competences, to demonstrate identity, to express themselves, to create pleasure experiences, and finally to compensate for failures in other areas of everyday life or problems that remain unsolved (Reisch 2002). Abuse of the compensation symbolic function of consumer goods might especially lead to the development of compulsive buying.

The above presented explanations account for the expectations that the Polish youth and young adults are characterized by compensative and compulsive buying to a greater extent than the remaining part of the population (Hypothesis 2).

Numerous studies draw attention to the negative correlation between self-esteem and compulsive buying. The rule was evidenced already by O’Guinn and Faber (1989), who stated a significantly lower self-esteem by compulsive buyers than by non-compulsive buyers. Studies carried out, e.g., in Canada (d’Astous et al. 1990), Germany (Lange 1997; Scherhorn et al. 1990), Poland, South Korea (Lange et al. 2005), or in Hungary (Maraz et al. 2015b) on the sample of adults or youth showed the same correlations. The connections between self-esteem and compensative as well as compulsive buying under conditions of consumer society’s consumerism are quite obvious. Members of the society believe that “meaning and satisfaction in life are to be found through the purchase and use of consumer goods” (Goodwin et al. 2008, p. 4). This life strategy leads to unavoidable failures and disappointments because very few consumers are able to keep up with the changing fashion, novelties appearing on the market, new consumer trends, and social compulsion to imitate the wealthiest. A weakened self-esteem might be an obvious consequence of the individual’s failures in the consumer society, while compensative buying appears as a simple means to improve it. With time, compensative buying can turn into compulsive buying.

The social acceptance of materialistic values in Poland is growing, although the development of consumerism is limited to economic and cultural reasons. Firstly, the purchasing power of an average Pole is 50.6% of the EU average (GfK Group 2019); secondly, consumerism is disapproved by Christianity, while this religion plays an important role for a significant part of Poles. For example, the support of the Schwartz scale statement “It is important for this person to be rich” increased from 24.9% in 2005 to 30.3% in 2012 (aggregated answers “very much like me,” “like me,” “somewhat like me”) (WVS 2012). For this reason, a stronger susceptibility to compensative and compulsive purchase going together with a weakened self-esteem is expected as a reaction to the growing consumerism orientation in the Polish society (Hypothesis 3).

The phenomena of consumer society and consumerism are strictly connected with materialism which is acknowledged as the most important cultural factor of compulsive buying. It was already O’Guinn and Faber (1989) who paid attention to the positive correlation between both variables. Harnish and Bridges (2015) found strong correlation between compulsive buying scale and material values scale short form of Richins and Dawson (1992) among US-American students. Otero-López et al. (2011), who conducted studies among women in Spanish Galicia, indicated strong correlations between compulsive buying and particular dimensions of the full materialism values scale of Richins and Dawson (1992): acquisition importance, success, and happiness. Studies in Estonia confirmed the findings. For example, while only 6% of respondents who buy rationally agreed with the statement “I admire people who have expensive homes, cars and clothes,” the ratio among compulsive buyers was 38% (Raudsepp and Parts 2014). Dittmar (2005) concluded her research results in the same way – persons valuating materialism display a stronger susceptibility to compulsive buying than persons more distanced from this life orientation.

In general, people attaching more importance to the possession of material goods and the symbols connected with them are less happy and more insecure (Benson et al. 2010). As a consequence, they are more susceptible to seeking a compensation in the world of consumer goods and shopping. Ultimately, excessive compensative buying might turn into compulsive buying. For this reason, it is expected that persons characterized by advanced materialism display susceptibility to compensative and compulsive buying to a greater extent than persons less attached to materialism (Hypothesis 4).

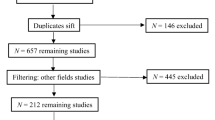

Method of the Study

The survey about compulsive buying was conducted in Poland in 2017 on a statistically representative sample of 1,121 Poles aged 18 years old and over who were married or in an informal partnership.Footnote 1 The study was carried out using computer-assisted web interview at the respondent’s home. The tendency for compulsive buying was measured by the German Compulsive Buying Indicator (GCBI; Raab et al. 2005). Respondents expressed their opinions about 16 statements using a 4-point scale from 1 (“I don’t agree”) to 4 (“I totally agree”).

First, unidimensionality, reliability, and normal distribution of the results on the scale were checked. The GCBI scale appeared as one-dimensional (KMO above 0.5; significance of Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity below 0.05; eigenvalue of the first component = 8.23; % of variance = 51.44). In the factor analysis, only one component was extracted, and the solution could not be rotated. Based on the results, unidimensionality of the scale can be pointed out. The scale achieved a very satisfying degree of reliability at the same time (Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.94). It means that a high degree of internal consistency of the GCBI can be assumed. The coefficients of skewness and kurtosis indicated that the distribution of the GCBI scale is approximately normal because neither of the values exceeds the interval between − 1 and + 1 (Skewness = 0.30; Kurtosis = − 0.55). It allows applying the t-student test for two independent samples or the one-way ANOVA analysis as well as the stepwise linear regression analysis. To sum up, the GCBI scale seems to be especially useful to measure compulsive buying in Poland.

Results

Prevalence of Compulsive and Compensative Buying

Following O’Guinn and Faber (1989) and Faber and O’Guinn (1992), respondents were classified as compulsive buyers if they achieved the results on the CBS scale of at least to two standard deviations above the means. Respondents who achieved the result between one and two standard deviations were classified as compensative buyers. Because the mean value on the GCBI scale equalled 31.79 and the standard deviation 9.75, those respondents were classified as compulsive buyers who achieved at least the result of 51 on the scale. In total, 2.9% of such cases were found in the general population. Those respondents who achieved the result of 41–50 were classified as compensative buyers. Of those cases, 15.8% were in the whole sample. In general, 18.7% of Poles aged 18 years old and more who were married or in a partnership displayed susceptibility to compulsive or compensative buying.

Factors of Compulsive and Compensative Buying

Gender

The data show that Poles are differentiated by gender in reference to compulsive and compensative buying. Although the percentages of compulsive buyers among women and men are similar (3.2% and 2.7%, respectively), the shares of compensative buyers are more differentiated (17.4% and 14.2%, respectively). The average value on the GCBI scale was 33.04 for women and 30.53 for men. The t-student test for two independent samples makes it possible to reject H0 according to which the mean values on the GCBI scale for men and women are equal (t(1,121) = − 4.350, p ≤ 0.05). Women then show a stronger susceptibility to compulsive buying than men.

Age

To examine the differences between age groups concerning the mean values on the GCBI scale, the sample was divided into four approximately equal subgroups: 18–35 years old (N = 281), 36–45 years old (N = 271), 46–57 years old (N = 281), and 58 years old up (N = 288). Comparing the mean values on the GCBI scale among the subgroups, the following tendency is observed – a weaker susceptibility to compulsive buying goes with an increasing age (18–35 years old, 33.86; 36–45 years old, 32.54; 46–57 years old, 31.18; + 58 years old, 29.66). At the same time, the shares of compulsive and compensative buyers decrease in higher age groups (Table 1).

The highest percentage of compulsive buyers was found out in the age groups of 18–35, whereas the lowest percentage among persons aged 58 years old and over. The same conclusion can be drawn in case of compensative buying. In total, about 1/4 of Poles aged 18–35 years old buy compulsively or compensatively, and the rate systematically decreases along with older age groups.

Using the one-way ANOVA analysis, the differences of mean values between particular age groups on the GCBI scale were proved if the differences were statistically significant. The usage of the ANOVA is possible because the normal distribution of the dependent variable as well as the homogeneous variance in particular age groups are observed. The significance p = .247 (Levene’s test) makes it possible to acknowledge H0 assuming that the difference of the variance in the tested groups is not statistically significant. The result of the one-way ANOVA points out to at least one pair of mean values differing from one another statistically significantly: F = (3,1119) = 9.926; p = 0.001. Hence, H0, assuming that mean values on the GCBI scale do not differ in the examined age groups, is rejected.

The post hoc test shows that some of the mean value pairs differ from one another in a statistically significant way. Persons aged 18–35 years old achieve a statistically significant higher mean value on the GCBI scale than persons aged 46 years old and over (18–35 vs. 46–57, M.D. = 2.68; p ≤ 0.05; 18–35 vs. 58+, M.D. = 4.20; p ≤ 0.05). The same conclusion can be drawn comparing the mean values of the age groups of 36–45 years old and 58 years old and over (M.D. = 2.88; p ≤ .05). It means that persons aged 18–35 years old show a stronger susceptibility to compulsive buying than persons aged 46 years old and over, while persons aged 36–45 years old are characterized by a stronger susceptibility to compulsive buying than persons aged 58 years old and over.

Self-Esteem

The data indicate a growing susceptibility to compulsive/compensative buying along with a decreasing self-esteem measured by the scale of Morris Rosenberg (1965), which in this study shows a satisfying level of reliability (Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.85). To examine the differences of mean values basing on the ANOVA procedure, the self-esteem scale from 10 to 40 was aggregated to four approximately equal subgroups: subgroup 1 characterized by the lowest self-esteem (10–26 points), subgroup 2 of 27–29 points, subgroup 3 with 30–33 points, and subgroup 4 with the highest self-esteem (34–40 points).

The mean values achieved on the GCBI scale clearly decrease with the increasing self-esteem (subgroup 1, 37.41; subgroup 2, 32.58; subgroup 3, 30.11; and subgroup 4, 26.30). As a result, the percentage of compulsive and compensative buyers increases along with the growing self-esteem (Table 2).

The highest percentage of compulsive and compensative buyers was observed among the respondents who were characterized by the lowest self-esteem. On the contrary, the lowest percentage of compulsive and compensative buyers was indicated among those respondents whose self-esteem score at the highest level. In total, nearly 2/5 of Poles characterized by the lowest self-esteem buy compulsively or compensatively, whereas the rate clearly declines with the higher levels of self-esteem.

Because a normal distribution of the dependent variable and homogeneous variance in the self-esteem subgroups are observed, the one-way ANOVA again enables examining the statistical significance of differences between the mean values achieved by the subgroups on the GCBI scale. The significance p = 0.369 (Levene’s test) confirms hypothesis H0 that the difference of the variance in the tested subgroups is not statistically significant. The result of the one-way ANOVA points out to at least one pair of mean values differing from each other statistically significantly: F = (3,1119) = 75.878; p = 0.001. The post hoc test shows that all mean value pairs differ from each other in a statistically significant way (Table 3).

Persons characterized by the lowest self-esteem (subgroup 1) achieve a statistically significantly higher mean value on the GCBI scale than persons characterized by a higher self-esteem. Representatives of subgroup 2 achieve a statistically significantly higher mean value on the GCBI scale than persons scoring higher on the self-esteem scale. At the same time, persons of this type achieve a statistically significantly lower mean value on the GCBI scale than persons characterized by the lowest self-esteem. The rule is the same in the case of persons belonging to subgroup 3: The mean value on the GCBI scale is lower in comparison with people with a lower self-esteem but higher in comparison with persons with the highest self-esteem. It means susceptibility to compulsive buying is growing together with a decreasing self-esteem.

Materialism

The further variable differentiating results on the GCBI scale is materialism understood as a life orientation permeated with the belief that purchase, possession, and consumption are the main criteria of happiness. Personal relationships or achievements play a secondary role (Richins and Dawson 1992). To measure materialism, the Polish version of the Richins and Dawson’s materialism scale was used (Górnik-Durose 2002).

The scale including 20 statements is characterized by a satisfying reliability (Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.83). Hence, the responses to the statements on the Likert 7-point scale were aggregated within four approximately equal subgroups to examine the differences of mean values basing on the ANOVA procedure: subgroup 1 characterized by the lowest level of materialism (20–62), subgroup 2 with 63–74 points, subgroup 3 with 75–81 points, and subgroup 4 showing the highest level of materialism (82–240 points).

According to expectations, the materialistic orientation increases along with the growing mean values on the GCBI scale (subgroup 1, 25.76; subgroup 2, 29.25; subgroup 3, 34.17; subgroup 4, 38.01). As a result, the percentage of compulsive and compensative buyers increases together with the growing level of materialism.

Results of the analysis in the cross tabs confirm without any doubts that persons preferring materialism show a significantly stronger susceptibility to compulsive/compensative buying in comparison with those who find this life orientation less important (Table 4).

Almost 1/10 of respondents characterized by the highest level of materialism show susceptibility to compulsive buying. Every third person of this type buys compensatively. It means that more than 2/5 of the subpopulation characterized by advanced materialism buy compulsively or compensatively. The share of compensative and compulsive buyers in the subpopulation preferring materialism to a less extent is significantly lower. Only about 1% of people characterized by the lowest level of materialism belong to the segment of compulsive buyers. In total, less than 1/20 of persons rejecting materialism buy compulsively or compensatively.

Like at previous stages, the one-way ANOVA was applied to prove if the mean values achieved by the materialism subgroups on the GCBI scale differ statistically significantly. Because the significance p = 0.001 (Levene’s test) evidences a lack of the satisfying statistical significance of the difference between variance in the tested groups, the correction of Welch was introduced. The result of the one-way ANOVA indicates at least one pair of mean values differing from each other statistically significantly: F = (3,1119) = 108.291; p = 0.001. The post hoc test shows that all of the mean value pairs differ from each other in a statistically significantly way (Table 5).

The results of the post hoc test point out that persons characterized by the lowest level of materialism (subgroup 1) achieve a statistically significantly lower mean value on the GCBI scale than persons placed higher on the materialism scale. Persons belonging to subgroup 2 achieve a statistically significantly lower mean value on the GCBI scale than persons scoring higher on the materialism scale. At the same time, persons of this type achieve a statistically significantly higher mean value on the GCBI scale than persons characterized by the lowest level of materialism. The rule is the same in case of persons belonging to the further subgroups of materialism: The mean value on the GCBI scale is higher in comparison with people characterized by a lower level of materialism but lower in comparison with persons representing a highest level of materialism. It means susceptibility to compulsive buying is growing along with an increasing level of materialism.

Materialism, Self–Esteem, Age, and Gender as Predictors of Compulsive Buying

Relations between compulsive buying and independent variables were examined based on the linear stepwise regression analysis. The predictors were entered in three steps starting with the variable which explains compulsive buying to the greatest extent. Materialism was entered first (Step 1), then self-esteem (Step 2), followed by age (Step 3), and gender (Step 4).

Table 6 presents coefficients after each independent variable was added. Materialism is the key variable which explains compulsive buying to the greatest extent. Furthermore, materialism and self-esteem remain constant and unaffected by the addition of age and gender. Basing on Step 2, a growth of susceptibility to compulsive buying by 0.261 points (± 0.017) on the GCBI scale is expected with each increase of materialism by 1 point. An opposite effect is observed in case of self-esteem. Here, the rule is as follows: The greater self-esteem, the lower result on the GCBI. An increase of self-esteem by 1 point means a loss of 0.531 points on the GCBI. Both predictors account for 30.3% of the variance of the GCBI. The above presented model is statistically significant.

If age is added in Step 3, a growth of susceptibility to compulsive buying along with increasing materialism by 1 point can be assumed on a nearly the same level as in the previous model (by 0.251; ± 0.017). The results concerning self-esteem keep stable, too – an increase of self-esteem by 1 point means a loss of 0.529 points on the GCBI scale. Meanwhile, increasing age causes a further decrease of susceptibility to compulsive buying, although this effect is rather weak – if age increases by one year, the result on the GCBI scale decreases only by 0.074. Comparing the results for age with other predictors, the role of age in the explanation of susceptibility to compulsive buying is secondary. Age provides a very slight increase of the explained variance adding only a further 1% to the explained variance in the prediction of compulsive buying (31.3%).

Finally, if gender is included in the model, the effect of materialism and self-esteem on the GCBI is the same as in the previous models. A growth of susceptibility to compulsive buying by 0.255 (± 0.017) on the GCBI scale can be assumed along with an increase of materialism by 1 point, while an increase of self-esteem by 1 point means a loss of 0.537 points on the GCBI scale. The addition of gender in the model minimalizes the importance of age. Admittedly, the effect of age on the GCBI is statistically significant but very weak; if age increases by one year, the result on the GCBI scale decreases only by 0.043. The role of gender in the explanation of the GCBI is clear – women show a stronger susceptibility to compulsive buying than men, although the role of gender in the explanation of the GCBI in the analysed model is rather weak – if a person is a woman, the result on the GCBI scale should increase by 2.294 points (± 0.514). Again, gender, like age, provides a very modest growth of the explained variance adding a further 1.1% to the explained variance in the prediction of compulsive buying (32.4%).

To sum up, the meaning of demographic variables such as age and gender for the prediction of compulsive buying is limited. Whether susceptibility to compulsive buying is stronger or weaker depends on materialism and self-esteem to a much greater extent. On the one hand, the stronger materialistic orientation, the stronger susceptibility to compulsive buying. On the other hand, the best protection against compulsive buying is a healthy self-esteem. Admittedly, susceptibility to compulsive buying is stronger in younger than in older people as well as in women rather than in men, but both factors are not crucial for the development of compulsive buying comparing with materialism and self-esteem, which emerged as the strongest predictors of compulsive buying.

Discussion

In accordance with our expectations, we observed the phenomenon of compulsive and compensative buying in the Polish society, although the extent of susceptibility is weaker than in West Europe or in comparison with the USA. The prevalence of compulsive buying on the level of about 3% among the population aged 18 and over should be assessed as rather low. The rate is about twice lower in comparison with most compared countries (Germany 8%, Austria 8%, Estonia 8%, Spain 7%, Denmark 6%, and the USA 6%). An exception refers to Hungary, where 2% of compulsive buyers were observed. Of course, it has to be taken into consideration that surveys conducted in particular countries are largely incomparable because of different sampling and scales of compulsive buying, varied techniques of data collection, or different periods of carrying out empirical measurements.

On the other hand, the lower rate of compulsive buyers in Poland as compared with West Europe or with the USA may be explained by a lower economic development, which results in less developed marketing and advertising activities, electronic retailing, and online shopping. For instance, the advertising market in the USA in 2015 amounted to the value of about USD 565 per capita annually, in Great Britain USD 380, and in Germany USD 260. The value of the Polish market was 5–10 times lower and achieved USD 52 at the same time (Pallus 2016). The value of e-commerce market in the USA in 2015 achieved the level of USD 1,058 per capita annually (U.S. Department of Commerce 2017). In Poland the ratio was four times lower and amounted to USD 244 an inhabitant (Rzeczpospolita 2016). Meanwhile, the development of online shopping is considered an important factor of compulsive buying (Raab and Neuner 2006).

The reasons for the relatively low ratio of compulsive buyers in the Polish society can be looked for in different cultural conditions in comparison with the societies of West Europe or the USA. One of them may be the development of consumer society in Poland, which is weaker in comparison with the countries from West Europe or with the USA. Due to the socialist period between 1945 and 1989, which was characterized by an insufficient satisfaction of citizens’ economic needs, consumerism could not spread among the Poles to the degree it did in Western Europe or North America.

A further cultural condition is the role of religion in everyday life. On the one hand, the materialistic orientation is one of the important factors of compulsive buying. On the other, materialism and consumerism are decisively disapproved by Christianity. Hence, susceptibility to compulsive or compensative buying should be lower in those societies where Christianity plays an important role. The rate of Poles who define themselves as religious amounts to the level of 86%. For example, the ratio is about twice higher in comparison with Germany (50%), the Netherlands (44%), or Spain (40%). It is significantly higher than in the USA, too (67%). In total, only 7% of Poles declare that they never attend religious services. The ratio in the above compared countries is even a few times higher: Spain (53%), the Netherlands (53%), Germany (34%), and the USA (30%) (WVS 2012). The relatively large prevalence of religious practices among Poles may be one factor which holds back the development of consumerism and compulsive as well as compensative buying in this connection.

Compensative buying has a noticeably greater range in the Polish society than compulsive buying. About 16% of Poles aged 18 and over practise this buying style. A comparison of the results with values measured in other countries shows that the prevalence of compensative buying in Poland remains on the average level. For example, the ratio of 16% is higher than the value found out in Denmark (10%) but lower in comparison with the rate observed in Austria in 2010 (19%).

Our study confirms the correlations between compulsive buying and some socio-demographical, individual, and cultural variables discovered in other societies. As expected, susceptibility to compulsive buying goes along with an increasing materialistic orientation, while susceptibility to compulsive buying declines with a growing age and self-esteem. In addition, women display a stronger susceptibility to compulsive buying than men. The results of the regression analysis show that a high level of materialism and weak self-esteem are the most important factors of compulsive buying, while the roles of age or gender are relatively marginal. Then, psychical and cultural conditions are decisive for the development of compulsive buying, which explains why the thesis about the simultaneous development of consumer society and compulsive as well as compensative buying is justified. Materialism is an immanent part of consumerism which influences consumers’ beliefs that purchase and possession of material goods secure social prestige and satisfaction in life. At the same time, consumer society makes the development of healthy self-esteem difficult because an access to socially desirable goods is limited and members of consumer society suffer defeats during the consumeristic race for social position. The empirical findings make it possible to assume the further development of compulsive and compensative buying which will be a consequence of the developing consumer society characterized by a prevalent materialistic orientation and a disturbed self-esteem.

Conclusions

We pointed to the possibility that the phenomenon of compulsive and compensative buying has a universal character and appears in societies to different extents being conditioned socially, economically, and culturally. Indeed, the direction of the observed correlations does not differ from the results indicated in other countries in most cases, although the range of compulsive buying in Poland is significantly below average. It is worth to consider that probably the real range of compulsive buying may be significantly greater than the reported threshold of 10% in most countries. Firstly, the quantitative research requires the consciousness of the measured behaviours, which is not quite obvious because of impulse or routine buying. Some buyers may be unaware that they buy compulsively or compensatively or they deny the fact. Secondly, compulsive buying often remains invisible in the social surroundings. It is supported by so-called consumption culture, which is intensively developing in the consumer societies. “Real working people find most of their life’s pleasures in consumption. What is more, they do not simply swallow whatever marketers throw at them like so many mindless automatons; they create their own meanings out of the products with which they chose to surround themselves. In fact, insofar as they fashion identities for themselves, those identities are largely based on the cars they drive, clothes they wear, music they listen to, and video they watch” (Graeber 2011, p. 490). Under these conditions, the purchasing acts are perceived positively as harmless acts. It is very difficult to notice that the acts may be indicators of a behavioural addiction. Since compulsive buying is now recognized as a social problem and maybe many compulsive buyers are unaware that they do have a problem or they deny that it is a problem, we urgently need more studies on this issue.

Implications for Consumer Policy

The obtained data allow to draw some conclusions for consumer policy. Firstly, low self-esteem is one of the most important factors of compulsive buying and other behavioural addictions. Usually, roots of low self-esteem are to find in childhood or in youth due to specific socialization such as authoritarian or overprotective upbringing styles leading to a distortion of both an individual’s autonomy and healthy feeling of one’s own value (Lange 1997). Also, the empirical data show that susceptibility to compulsive buying characterizes younger people to a significantly greater extent than the elderly. It means compensative and compulsive buying is often a response of children and youth to negative developments in the socialization process or a symptom of youthful protest. This effect is additionally supported by materialism. Consumer goods and their symbolic values are more important for younger than for elderly people. A low self-esteem coupled with a strong materialism orientation pose a really high potential for the development of compensative and compulsive buying, especially among children and youth. It shows how important the process of upbringing for the role of consumer is. Due to a rapid development of consumer society (new technologies, digitalization of everyday life, new kinds of communication channels, new role of social media differentiating social positions), parents are often not able to manage the task efficiently. For this reason, the special programmes focused on explaining the role of cultural, societal, personal, psychical, and marketing factors of consumer behaviours offered by educational institutions should support this upbringing process in the area of buying and consumption. The development of the special education programmes would be in the line with the main tasks of consumer policy – consumer education, consumer information, and consumer protection (Thorelli 1972).

Limits of the Present Research

Some limits of the presented study should be openly mentioned. Firstly, the sample of the survey was limited to the respondents who are married or in an informal partnership. How far can the above presented findings be treated as representative for the whole society? The question is justified because persons suffering from compulsive buying often experience a crisis of relationships within their family resulting in a divorce or separation. The actual share of compulsive buyers in the total Polish population might be higher than reported in this paper. The concerns are justified but to a limited extent. The study conducted in 2016 on the nationwide statistically representative sample of Poles aged 15 and over showed a 4.4% rate of compulsive buyers (Adamczyk 2018). The difference amounts to 1.5% and does not exceed the statistical error. Under the specific cultural conditions of the Polish society characterized by a relatively low percentage of divorced/separated persons (5.1% according to WVS 2012, which is significantly lower than, e.g., in the Netherlands 8.5%, Sweden 10.5%, Germany 11.5%, and the USA 11.9%), the representativeness of the above presented sample can be assumed for the whole society.

The obtained data could be influenced by the effect of social desirability bias, first of all, in case of the older generation. This effect is observable in the social research, especially if the method of questionnaire is thematically connected with the topic of addiction. As a consequence, the conclusions about compulsive buying base on the declarations, not on actual behaviour, which causes a growing danger of the social desirability bias effect. The appearance of the effect is greater in case of older than younger people because of different life values acknowledged by the subgroups and of a greater susceptibility of the older subgroups to yielding to social control. In addition, the study is not longitudinal; hence, the conclusions are possible about the coexistence of the analysed variables but not about any causal relations.

Notes

The limitation of the sample was connected with another aim of the study – measuring the value orientation of Polish families.

References

Achtziger, A., Hubert, M., Kenning, P., Raab, G., & Reisch, L. A. (2015). Debt out of control: The links between self-control, compulsive buying, and real debts. Journal of Economic Psychology, 49, 141–149.

Adamczyk, G. (2018). Phenomenon of compensative and compulsive buying in Poland. A socio-economic study. Economic and Environmental Studies, 4, 1181–1200.

Antonides, G., & van Raaij, F. W. (1998). Consumer behaviour: A European perspective. New York, NY: Wiley.

Becker, G. S. (1976). The economic approach to human behavior. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Benson, A. L., Dittmar, H., & Wolfsohn, R. (2010). Compulsive buying: Cultural contributors and consequences. In E. Aboujaoude & L. M. Koran (Eds.), Impulse control disorders (pp. 23–33). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Black, D. W. (2011). Epidemiology and phenomenology of compulsive buying disorder. In J. E. Grant & M. N. Potenza (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of impulse control disorders (pp. 196–207). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Bleuler, E. (1934). Textbook of psychiatry. New York, NY: The Macmillan Company.

Claes, L., Luyckx, K., Vogel, B., Verschueren, M., & Müller, A. (2018). Identity processes and clusters in individuals with and without pathological buying. Psychiatry Research, 267, 467–472.

D’Astous, A., Maltais, J., & Roberge, C. (1990). Compulsive buying tendencies of adolescent consumers. Advances in Consumer Research, 17, 306–312.

Dittmar, H. (2005). Compulsive buying – A growing concern? An examination of gender, age, and endorsement of materialistic values as predictors. British Journal of Psychology, 96, 467–491.

Faber, R. J., & O’Guinn, T. C. (1992). A clinical screener for compulsive buying. Journal of Consumer Research, 19, 459–469.

Faber, R. J., O’Guinn, T. C., & Krych, R. (1987). Compulsive consumption. Advances in Consumer Research, 14, 132–135.

Fässler, B. (1997). Drogen zwischen Herrschaft und Herrlichkeit. Der Umgang mit Drogen als Spiegel der Gesellschaft. Solothurn: Nachtschatten Verlag.

GfK Group. (2019). GfK purchasing power Poland 2018. Nuremberg: GfK.

Goodwin, N., Nelson, J. A., Ackerman, F., & Weisskopf, T. (2008). Consumption and the consumer society. A GDAE teaching module on social and environmental issues in economics. Medford, MA: Tufts University.

Górnik-Durose, M. (2002). Psychologiczne aspekty posiadania – między instrumentalnością a społeczną użytecznością dóbr materialnych. Katowice: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Śląskiego.

Graeber, D. (2011). Consumption. Current Anthropology, 52(4), 489–511.

Harnish, R. J., & Bridges, R. K. (2015). Compulsive buying: The role of irrational beliefs, materialism, and narcissism. Journal of Rational-Emotional Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy, 33, 1–16.

Harnish, R. J., Bridges, R. K., Nataraajan, R., Gump, J. T., & Carson, A. E. (2018). The impact of money attitudes and global life satisfaction on the maladaptive pursuit of consumption. Psychology and Marketing, 35(3), 189–196.

Kearney, M., & Stevens, L. (2012). Compulsive buying: Literature review and suggestions for future research. The Marketing Review, 12(3), 233–251.

Kollmann, K., & Unger, A. (2010). Kaufsucht in Österreich 2010. Wien: Kammer für Arbeiter und Angestellte für Wien.

Koran, L. M., Faber, R. J., Aboujaoude, E., Large, M. D., & Serpe, R. T. (2006). Estimated prevalence of compulsive buying behavior in the United States. Am I Psychiatry, 163, 1806–1812.

Kraepelin, E. (1909). Psychiatrie. Ein Lehrbuch für Studierende und Ärzte. Leipzig: Verlag von Johann Ambrosius Barth.

Lange, E. (1997). Jugendkonsum im Wandel. Konsummuster, Freizeitverhalten, soziale Milieus und Kaufsucht 1990 und 1996. Opladen: Leske + Budrich.

Lange, E., Choi, S., Yoo, D., & Adamczyk, G. (2005). Jugendkonsum im internationalen Vergleich. Eine Untersuchung der Einkommens-, Konsum- und Verschuldungsmuster der Jugendlichen in Deutschland, Korea und Polen. Opladen: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

Maraz, A., Eisinger, A., Hende, B., Urban, R., Paksi, B., Kun, B., et al. (2015a). Measuring compulsive buying behaviour: Psychometric validity of three different scales and prevalence in the general population and in shopping centres. Psychiatry Research, 225, 326–334.

Maraz, A., van den Brink, W., & Demetrovics, Z. (2015b). Prevalence and construct validity of compulsive buying disorder in shopping mall visitors. Psychiatry Research, 228, 918–924.

Maraz, A., Griffiths, M. D., & Demetrovics, Z. (2016). The prevalence of compulsive buying: A meta-analysis. Addiction, 111, 408–419.

Müller, A., Mitchell, J. E., & de Zwaan, M. (2015). Compulsive buying. The American Journal on Addictions, 24, 132–137.

Neuner, M., Raab, G., & Reisch, L. A. (2005). Compulsive buying in maturing consumer societies: An empirical re-inquiry. Journal of Economic Psychology, 26, 509–522.

O’Guinn, T. C., & Faber, R. J. (1989). Compulsive buying: A phenomenological exploration. Journal of Consumer Research, 16(2), 147–157.

Otero-López, J. M., & Villardefrancos Pol, E. (2015). Compulsive buying and life aspirations: An analysis of intrinsic and extrinsic goals. Personality and Individual Differences, 76, 166–170.

Otero-López, J. M., Villardefrancos Pol, E., Bolaño, C. C., & Santiago Mariño, M. J. (2011). Materialism, life-satisfaction and addictive buying: Examining the causal relationships. Personality and Individual Differences, 50, 772–776.

Pallus, P. (2016). Reklama na świecie się rozpędza. W Polsce jej wzrost nieco hamuje. Business Insider Polska. Retrieved from: http://businessinsider.com.pl/media/reklama/rynek-reklamy-w-2016-roku-w-polsce-i-na-swiecie/34zcq3b. Accessed 13 Nov 2017.

Raab, G., & Neuner, M. (2006). Kaufsucht im Internet - Eine Studie am Beispiel des Kauf- und Auktionsverhaltens auf Ebay. NeuroPsychoEconomics, 3(1), 34–42.

Raab, G., Neuner, M., Reisch, L. A., & Scherhorn, G. (2005). Screeningverfahren zur Erhebung von kompensatorischem und süchtigem Kaufverhalten (SKSK). Göttingen: Hogrefe.

Raudsepp, M., & Parts, O. (2014). Compulsive buying in Estonia. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 156, 414–417.

Reisch, L. A. (2002). Symbols for Sale: Funktionen des symbolischen Konsums. In C. Deutschmann (Ed.), Die gesellschaftliche Macht des Geldes (pp. 226–249). Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Reisch, L. A., Gwozdz, W., & Raab, G. (2011). Compulsive buying in Denmark: The first study on Danish consumers’ tendency to compulsive buying. Frederiksberg: Institut for interkulturel Kommunikation og Ledelse (IKL), Copenhagen Business School.

Richins, M. L., & Dawson, S. (1992). A consumer values orientation for materialism and its measurement: Scale development and validation. Journal of Consumer Research, 19, 303–316.

Rosenberg, M. (1965). Society and adolescent self-image. New York, NY: Princeton University Press.

Rzeczpospolita. (2016). Rynek e-commerce w Polsce – specyfika, trendy, praca. Rzeczpospolita Biznes. Retrieved from: http://www.rp.pl/Biznes/160619670-RYNEK-E-COMMERCE-W-POLSCE%2D%2Dspecyfika-trendy-praca.html. Accessed 13 Nov 2017.

Scherhorn, G., Reisch, L. A., & Raab, G. (1990). Addictive buying in West Germany: An empirical study. Journal of Consumer Policy, 13, 355–387.

Scherhorn, G., Reisch, L. A., & Raab, G. (2001). Kaufsucht. Bericht über eine empirische Untersuchung (Working Paper No. 50). 10th enlarged edition (Orig. 1990). Stuttgart: University of Hohenheim, Department of Consumption Theory and Consumer Policy.

Thalemann, C. N. (2009). Verhaltenssucht. In D. Batthyány & A. Pritz (Eds.), Rausch ohne Drogen. Substanzungebundene Süchte (pp. 1–17). Wien: Springer Verlag.

Thorelli, H. B. (1972). A concept of consumer policy. In SV – Proceedings of the Third Annual Conference of the Association for Consumer Research (pp. 192–200). Chicago, IL: Association for Consumer Research.

U.S. Department of Commerce. (2017). New insights on retail e-commerce. Retrieved from https://www.commerce.gov/news/reports/2017/07/new-insights-retail-e-commerce. Accessed 13 Nov 2017.

Villella, C., Martinotti, G., Di Nicola, M., Cassano, M., La Torre, G., Gliubizzi, M. D., et al. (2011). Behavioural addictions in adolescents and young adults: Results from a prevalence study. Journal of Gambling Behavior. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-010-9206-0.

WVS. (2012). World Values Survey. Retrieved from http://www.worldvaluessurvey.org/WVSOnline.jsp. Accessed 13 Nov 2017.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Adamczyk, G., Capetillo-Ponce, J. & Szczygielski, D. Compulsive Buying in Poland. An Empirical Study of People Married or in a Stable Relationship. J Consum Policy 43, 593–610 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10603-020-09450-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10603-020-09450-4