Abstract

We investigate the phenomenon of corruption in an experimental setting. The first treatment studies the role of reciprocity in establishing corrupt relationships between two agents. Corruption occurs when public officials accept bribes and reward the briber at the expenses of others. The second treatment introduces two features that negatively affect bribery: increasing the cost of bribery and introducing the monitoring agents. In this case, corruption occurs when the monitoring agent conceals the observed bribe-exchange. The last two treatments disentangle the effects of the two features affecting bribery. Our results show that high bribery cost and the presence of monitoring agents curb corrupt behaviors mildly.

.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

At the same time, several scholars focused on other aspects of corruption, such as the effects of grease payments to bureaucrats (Gonzalez et al. 2004), the phenomenon of embezzlement (Azfar and Nelson 2007), the corruption incentives generated by the procurement of inputs for public projects (Buchner et al. 2008), the role of whistle-blowing in the context of anti-trust policy (Apesteguia et al. 2007), and the case in which a particular principal-agent problem impacts public service delivery (Barr et al. 2009).

One small difference to AIR’s Negative Externality treatment is that the negative externalities are slightly smaller in total, because there were fewer subjects in one session.

The Triplets treatment shares some features with the relevant literature analysing the role of a third party in different experiments with the main difference being the more interactive role played by the monitoring agents in our case (Kahneman et al. 1986; Knez and Camerer 1995; Guth and van Damme 1998; Carpenter and Matthews 2004; Fehr and Fishbacher 2004; Bereby-Meyer and Niederle 2005).

Abbink and Wu (2017) also focus on the effect of reporting bribery but from a different perspective. In fact, they test regimes where both the client and official may self-report and regimes where only one party may self-report. Their results show that only enabling both parties to self-report is highly effective in deterring bribes being exchanged and corrupt favours being granted.

We are aware that public officials’ preferences may be driven also by the implicit risk of detection and punishment. However, in our experiment we do not explicitly control for such possibilities.

Although it is possible to incur in losses during the experiment, the show-up fee has been set in a way to avoid negative balances at the end of the sessions.

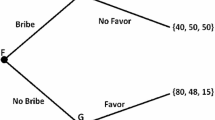

The game tree is incomplete in the sense that the final payoffs reported do not account for the decisions of all the other groups.

We conducted just one session of Pairs treatment at the AL.EX experimental laboratory of the University of Eastern Piedmont. The Mann–Whithney U test (MWU) found no significant difference between the average transfers and relative frequency of Y choice between the sessions ran in the two labs.

We are aware of the difference in the levels of the negative externality between the sessions because of their different sizes. However, given that these differences are relatively small, we do not expect to observe such a strong effect on individuals’ decisions.

We report the instructions regarding the Triplets treatment in the Appendix. The instructions of the other treatments are available from the author upon request.

All Spearman's ρ are significant at 1% level except for one (ρHT = 0.64) that is significant at 5%. The same result is shown in AIR. To provide further statistical significance, we calculate the Spearman’s ρ values for each independent observation and, then, use a one-sided sign test to show that positive ρ values are significantly more likely to happen than negative. The results confirm the previous findings.

In addition, we check whether the results of the Pairs treatment successfully replicate those of the Negative Externality treatment of AIR. In particular, the MWU test finds significant differences between both the average group offer and the average relative frequency of Y choice reached in the two treatments (p < 0.01). In particular, the Negative Externality treatment shows higher values of both variables than the Pairs treatment. The result of MWU test may be explained by the absence of a peak at a transfer of six tokens in the Pairs treatment that is reported in the AIR’s NE treatment instead. As already mentioned, a transfer of six tokens equalizes the payoffs between the briber and the public official in both treatments. Differently from the Pairs treatment, AIR provided payoff tables to participants that made this feature very salient and facilitated coordination so that players had to decide whether or not they wanted to engage in bribery. In the instructions of the Pairs treatment there were no such tables because we were not interested in making this point explicit. Moreover, the results of this comparison may be influenced by other factors such as the nationality of subjects, the number of subjects participating in the experiments, the software used to run the sessions.

We thank an anonymous referee for suggesting to check for negative reciprocity.

Also, in this case we report the moving average on the last five periods of observations.

Also, in this case we report the moving average on the last five periods of observations.

Cameron et al. (2009) design a one-shot three-player experiment with three stages where, in each group, one member is negatively affected by the corruption occurring between the other two members and may decide to punish the one accepting the bribe in the third stage of each period. The punishment produces a payoffs reduction for both the sender and the recipient. In contrast to our design, they do not allow for punishment towards the briber and, once the bribe is accepted, the public official cannot deviate from the reciprocal choice. The authors also find that corruption is punished in almost half of the cases.

References

Abbink K (2004) Staff rotation as an anti-corruption policy: an experimental study. Eur J Polit Econ 20:887–906

Abbink K (2005) Fair salaries and the moral costs of corruption. In: Kokinov B (ed) Advances in cognitive economics. NBU Press, Sofia

Abbink K (2006) Laboratory experiments on corruption. In: Rose-Ackerman S (ed) The handbook of corruption. Edward Elgar Publishers, Cheltenham

Abbink K, Hennig-Schmidt H (2006) Neutral versus loaded instructions in a bribery experiment. Exp Econ 9(2):103–121

Abbink K, Serra D (2012) Anti-corruption policies: lessons from the lab. Res Exp Econ 15:77–115

Abbink K, Wu K (2017) Reward self-reporting to deter corruption: an experiment on mitigating collusive bribery. J Econ Behav Organ 133:256–272

Abbink K, Irlenbusch B, Renner E (2000) The moonlighting game—an experimental study on reciprocity and retribution. J Econ Behav Organ 42:265–277

Abbink K, Irlenbusch B, Renner E (2002) An experimental bribery game. J Law Econ Organ 18(2):428–454

Armantier O, Boly A (2013) Comparing corruption in the laboratory and in the field in Burkina Faso and in Canada. Econ J 123(December):1168–1187

Apesteguia J, Dufwenberg M, Selten R (2007) Blowing the whistle. Econ Theor 31(1):143–166

Azfar O, Nelson W (2007) Transparency, wages, and the separation of powers: an experimental analysis of corruption. Public Choice 130(3–4):471–493

Barr A, Serra D (2009) The effects of externalities and framing on bribery in a petty corruption experiment. Exp Econ 12:488–503

Barr A, Lidelow M, Serneels P (2009) Corruption in public service delivery: an experimental analysis. J Econ Behav Organ 72:225–239

Basu K, Bhattacharya S, Mishra A (1992) Notes on bribery and the control of corruption. J Public Econ 48:349–359

Becker GS, Stigler GJ (1974) Law enforcement, malfeasance, and compensation of enforcers. J Legal Stud 3:1–18

Bereby-Meyer Y, Niederle M (2005) Fairness in bargaining. J Econ Behav Organ 56:173–186

Berg J, Dickhaut J, McCabe K (1995) Trust, reciprocity and social history. Games Econ Behav 10:122–142

Buchner S, Freytag A, Gonzalez L, Guth W (2008) Bribery and public procurement: an experimental study. Public Choice 137:103–117

Cameron L, Chaudhuri A, Erkal N, Gangadharan L (2009) Propensities to engage in and punish corrupt behaviour: experimental evidence from Australia, India, Indonesia and Singapore. J Public Econ 93(7):843–851

Carpenter J, Matthews PH (2004) Social reciprocity. Mimeo

Dufwenberg M, Gneezy U (2000) Measuring beliefs in an experimental lost wallet game. Games Econ Behav 30:163–182

Dusek L, Ortmann A, Lizal L (2005) Understanding corruption and corruptibility through experiments: a primer. Prague Econ Pap 14(2):147–162

Fehr E, Fishbacher U (2004) Third-party punishment and social norms. Evol Hum Behav 25:63–87

Fehr E, Gaechter S, Kirchsteiger G (1997) Reciprocity as a contract enforcement device: experimental evidence. Econometrica 65:833–860

Fisman R, Gatti R (2002) Decentralization and corruption: evidence across countries. J Public Econ 83:325–345

Frank B, Schulze GG (2000) Does economics make citizens corrupt? J Econ Behav Organ 43:101–113

Gonzalez L, Guth W, Levati V (2004) Speeding up bureaucrats by greasing them—an experimental study. Working Paper, MPI Jena

Guiso L, Sapienza P, Zingales L (2000) The role of social capital in financial development. Working Paper no. 7563, NBER

Guth W, van Damme E (1998) Information, strategic behavior and fairness in ultimatum bargaining: an experimental study. J Math Psychol 42:227–247

Hunt J (2005) Why are some public officials more corrupt than others? In: Rose-Ackerman S (ed) The Handbook of Corruption. Edward Elgar Publishers, Cheltenham

Hunt J, Laszlo S (2005) Bribery: who pays, who refuses, what are the payoffs? Working Paper no. 11635, NBER

Kahneman D, Knetsch JL, Thaler RH (1986) Fairness and the assumption of economics. J Bus 59:285–300

Knez MJ, Camerer C (1995) Outside options and social comparison in three-player ultimatum game experiments. Games Econ Behav 10:65–94

Marjit S, Shi H (1998) On controlling crime with corrupt officials. J Econ Behav Organ 34:163–172

Mauro P (1995) Corruption and growth. Q J Econ 110:680–712

Mocan N (2008) What determines corruption? International evidence from microdata. Econ Inq 46(4):493–510

Polinsky MA, Shavell S (1979) The optimal tradeoff between the probability and the magnitude of fines. Am Econ Rev 69:880–891

Rose-Ackerman S (1975) The economics of corruption. J Public Econ 4:187–203

Serra D (2012) Combining top-down and bottom-up accountability: evidence from a bribery experiment. J Law Econ Organ 28(3):569–587

Schulze GG, Frank B (2003) Deterrence versus intrinsic motivation: experimental evidence on the determinants of corruptibility. Econ Gov 4:143–160

Treisman D (2000) The causes of corruption: a cross-national study. J Public Econ 76(3):399–457

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank prof. Guido Ortona, prof. Carla Marchese and Dr. Marie-Edith Bissey for their hospitality and the use of the AL.EX. experimental laboratory of the University of Eastern Piedmont, Alessandria, Italy. I am grateful to Benedetto Bruno and Sebastiano Scirè for computerizing the experiment. I benefited from the comments of Mariana Blanco, the participants in seminars at Royal Holloway College (University of London), SIEP Conference 2006, COFIN Workshop Varese 2008, Royal Economic Society Meeting 2011, University of Salento 2014.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

1.1 Instructions

Welcome

You are taking part into an experiment on individual decision-making. At the beginning of the experiment you will be randomly assigned to one of three possible types of players: Player 1, Player 2 and Player 3 and allocated to one group. Each group is formed by three members, one for each possible type of player. Each participant will be assigned the same role and the composition of the group will remain same during the experiment.

For example, if you are randomly assigned type 1 player, the other two group members will be assigned the type 2 player and 3 player.

According to your decisions, to the decisions made by the other members of your group and to the decisions of the other participants in the lab, you can earn a considerable amount of money. The money you will earn will be paid confidentially to you, in cash, at the end of the experiment. The funds for this study have been provided by the University of Catania. If any of the instructions are unclear, or if you have any questions, please attract the attention of the experimenter by raising your hand. Please do not communicate with any other participants from now on.

This experiment will last for 30 periods. Each period is divided into four stages. The structure of each stage will be explained in details. The outcomes referring to any possible decisions of each group member are described in the diagram placed at the end of the instructions. Please, make sure that you have properly understood the diagram before making your choices.

Your profit will be measured in tokens and, at the end of the experiment, converted into euro at the following exchange rate of 1 token = 1 euro cent. In addition, you will receive a show-up fee of 5 euros.

1.1.1 Stage I

In this stage Player 1 is asked to make a decision. Player 1 has an endowment of nine tokens and he is asked to decide whether or not to transfer part of his endowment to Player 2. Player 1 can only send integer number of tokens from 0 to 9 to Player 2.

-

If Player 1 sends a positive amount of tokens, his outcome from the current period will be reduced by two tokens (transfer fee).

-

If Player 1 does not send any part of his endowment, then his outcome from the current period will remain unchanged. In this case, the experiment moves directly to Stage III.

1.1.2 Stage II

In this stage Player 2 is asked to make a decision. Player 2 is informed about the amount sent by Player 1 and, then, he decides whether to accept (A) or reject (R) the transfer.

-

If Player 2 accepts the transfer (A), then Player 1’s outcome from the current period is reduced by the amount of tokens he sent in Stage I. Differently, Player 2’s outcome from the current period is increased by the doubled amount that has been transferred in Stage I.

-

If Player 2 rejects the transfer (R), then Player 1’s outcome from the current period remains is reduced by two tokens (transfer fee) as described in Stage I.

-

Player 3 receives the information about the decision taken by Player 1.

1.1.3 Stage III

In this stage Player 2 is asked to make a decision.

-

Player 1 and Player 3 are informed on whether Player 2 has accepted or rejected the transfer.

-

Player 2 chooses between two possible alternative X or Y whose effects on individual outcomes are shown in the diagram.

1.1.4 Stage IV

In this stage Player 3 is asked to make a decision.

-

Player 1 and Player 3 are informed about the decision taken by Player 2.

-

Player 3 chooses between two alternatives D and C. The effects of those choices on individual outcomes are shown in the diagram.

-

Player 1 and Player 2 are informed on the choice of Player 3.

Each time any Player 3 chooses the alternative A in Stage IV, the current period outcomes of all the members of the other groups in the lab will be reduced by three tokens.

Given that there are six groups taking part into this experiment, the outcome of each player, regardless of his type, may be reduced by a maximum of 5 (groups) × 3 tokens = 15 tokens. The overall deduction caused by the decisions of the other groups in the lab will be announced at the end of the experiment.

After Stage IV, the period ends.

If you have any questions the experiment please raise your hand.

Good Luck!

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Finocchiaro Castro, M. To Bribe or Not to Bribe? An Experimental Analysis of Corruption. Ital Econ J 7, 487–508 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40797-020-00129-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40797-020-00129-w