Abstract

We prove a multivariate Lagrange-Good formula for functionals of uncountably many variables and investigate its relation with inversion formulas using trees. We clarify the cancellations that take place between the two aforementioned formulas and draw connections with similar approaches in a range of applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Consider a power series of the form

In a previous paper [23], we have expressed the inverse map \(\zeta (\nu )\) (that is \(\rho (z) = \nu \) if and only if \(z = \zeta (\nu )\)) with the help of a tree generating functional. The main focus is to formulate these results for uncountably many colors. An uncountable color palette is completely natural if one studies thermodynamic functionals for inhomogeneous systems in order to derive variational or PDE formulations in different areas, for example in classical density function theory, liquid crystals, heterogenous materials, colloid systems, system of molecules with various shapes or other internal degrees of freedom. This is because “colors” correspond to positions or other continuous degrees of freedom (e.g., orientations).

If \(\rho \) and z are taking only nonnegative values, as in the above mentioned applications, then the form (1.1) is natural.

For a single complex variable \(z\in \mathbb {C}\), the inverse reads

where \(T^\circ (\nu )\) solves

and one recognizes the generating function for weighted rooted trees whose root is a ghost (that is, the root does not come with powers of \(\nu \) in the generating function).

On the other hand, as is well-known, the coefficients of \(\nu \) in the inverse map \(\zeta (\nu )\) (and any functions of \(z=\zeta (\nu )\)) can be expressed in terms of the Lagrange inversion formula. Formally,

An additional integration by parts yields the more frequently encountered form of the Lagrange inversion formula

see e.g., [15, Appendix A6] or the recent survey [18]. The multivariate case is similar, with the determinant of a Jacobi matrix instead of the derivative \(\rho '(z)\). There is a variety of multivariate forms, see [17, 20, 29] and [4, 10, 26] for infinitely (countably) many variables.

Despite the large literature on Lagrange-Good inversion and the increasing interest it attracts from combinatorialists, to the best of our knowledge no analogue for uncountably many variables has been considered up to now. Exception are [12, 28], where combinatorial identities are generalized to an arbitrary number of variables; however, the concept of summability by Mendéz and Nava is a restriction which would not allow to treat the above-mentioned applications. The first aim of the present note is to fill this gap: we propose a multivariate Lagrange-Good formula for functionals of uncountably many variables (Theorem 3.1).

The second aim is to clarify the relation with the tree formula from Proposition 2.6 in [23]. Just as Gessel’s proof of the Lagrange-Good inversion formula for finitely many variables, our proof starts from a representation of the inverse in terms of trees. In contrast, determinants are associated with digraphs that may have cycles; equality arises because of cancellations as clarified in Proposition 3.4. There is actually more to this: when interested in proving asymptotic formulas and checking the validity (absolute convergence) of the power series, the tree formula is easier to handle. In fact, in [26], we had to show that the determinant was bounded and then in [23], we realized that the determinant is not actually there due to the cancellations and therefore we deduced better bounds with less effort. The observation that determinants might be a hindrance to asymptotic analysis is also behind determinant-free, so-called arborescent forms of Lagrange-Good, see [5, 8, 19].

It is noteworthy that Good’s original motivation [20, 21] for generalizing Lagrange’s inversion formula was the enumeration of various kinds of trees, thus starting from the functional equation satisfied by combinatorial generating functions. The antipodal view point is to start from the inversion problem, consisting in solving a given functional equation; then one has two options: either apply one of the versions of the Lagrange-Good inversion formula, or derive an expression for the solution directly with trees. Solving inversion problems with different types of trees is common practice in many areas: Butcher series in numerics, Gallavotti trees in RG group, Lindstedt series in KAM theory [16], algebra [6, 34], see Sect. 5 for more details and a discussion of the relation to the approach taken in this paper.

The article is organized as follows. Section 2 recalls the multi-variate formulas that we seek to generalize and introduces formal power series associated with uncountable spaces. In Sect. 3 we set up the problem and present the main result, which is then proven in Sect. 4. We draw connections to other inversion formulas based on trees in Sect. 5. “Appendix A” recalls some formulas for formal power series. For our proof, we propose a formalism of colored species with uncountable color space, which allows us to adapt the proof given by Gessel [17] for finitely many variables to the case of uncountably many variables; this formalism is described in detail in “Appendix B”.

2 Preliminaries

2.1 Multivariate Lagrange inversion

Here, we recall the form of the Lagrange inversion formula for formal power series in finitely many variables \(z_1,\ldots , z_d\in \mathbb C\) that we seek to generalize. For \(\varvec{n}= (n_1,\ldots , n_d) \in \mathbb {N}_0^d\) we write \(\varvec{z}^{\varvec{n}} = z_1^{n_1}\cdots z_d^{n_d}\) and \([\varvec{z}^{\varvec{n}}] F(\varvec{z})\) denotes the coefficient of the monomial \(\varvec{z}^{\varvec{n}}\) in the series F, i.e., if \(F(\varvec{z})= \sum _{\varvec{n}} f_{\varvec{n}} \varvec{z}^{\varvec{n}}\), then \([\varvec{z}^{\varvec{n}}] F(\varvec{z}) = f_{\varvec{n}}\).

Suppose, we are given a family \((A_i(z_1,\ldots , z_d))_{i=1,\ldots ,d}\) of formal power series whose coefficient of order zero vanishes, \(A_i(\varvec{0}) =0\). Define additional formal power seriesFootnote 1\(\rho _1,\ldots , \rho _d\) by

There is a uniquely defined family of power series \((\zeta _1,\ldots , \zeta _d)\) such that

as an equality of formal power series, furthermore \((\zeta _1,\ldots , \zeta _d)\) also satisfies

as an equality of formal power series in the variables \(\nu _1,\ldots , \nu _d\). Let \(\Phi (z_1,\ldots ,z_d)\) be yet another formal power series. Then,

Equation (2.4) follows from [17, Eq. (4.5)], see also Theorem 8(b) in [7, Chapter 3.2]. Variants for countably many variables are available [4, 10].

Specializing to \(\Phi (\varvec{z}) = z_k\) with \(k\in \{1,\ldots , d\}\), we obtain

compare (1.4) for \(d=1\). Conversely, Eq. (2.4) easily follows from Eq. (2.5) as well. Equation (2.5) allows us to express the coefficients of the unknown reverse series \(\zeta _i(\varvec{\nu })\) in terms of coefficients of the known series \(A_i(\varvec{z})\) and functions thereof. Equation (2.5) should be contrasted with tree formulas derived from the following functional equation (combining (2.1) and (2.3) )

see also Sect. 5.

Our goal is to generalize Eqs. (2.4) and (2.5) to a situation where the finite set \(\{1,\ldots , d\}\) is replaced with a possibly uncountable space \({\mathbb {X}}\), and to provide adequate combinatorial interpretations. The tree formula for the inverse in uncountable color space was already proven in [23], it is recalled in Sect. 4.2.

2.2 Formal power series

Let us briefly motivate the definition of formal power series adopted in [23, Appendix A]. A formal power series in finitely many variables \(z_1,\ldots , z_d\) may be written as

for some suitable family of coefficients \(a(\varvec{n})\), where \(\varvec{n} ! =n_1! \ldots n_d!\) but also as

with coefficients \(f_n(i_1,\ldots , i_n)\) that are invariant under permutation of the argument, where \( a(\varvec{n}) = f_n(i_1,\ldots , i_n)\), whenever \( \#\{ i_1, \ldots , i_d \, :\, i_n =j\} = n_j\) for all \(j\in \{1 , \ldots ,d\}\) and \(n = n_1 + \ldots + n_d\). Eq. (2.8) is less elegant than the multiindex formula (2.7) but redeems itself by a straightforward generalization to uncountable spaces. (Other benefits of Eq. (2.8) are discussed by Abdesselam in the context of Feynman diagrams and tensors [1, Sect. III].) If \(\{1,\ldots , d\}\) is replaced with a measurable space \(({\mathbb {X}},{\mathcal {X}})\) it is natural to replace sums with integrals and switch from a vector \((z_1,\ldots , z_d)\) to a measure \(z(\mathrm {d}x)\). Accordingly, the power series we are interested in are of the form

the coefficients consist of a scalar \(f_0\in \mathbb {C}\) and symmetric measurable functions \(f_n: {\mathbb {X}}^n\rightarrow \mathbb {C}\), \(n\in \mathbb {N}\). As usual for formal power series, we do not want to deal with questions of convergence and downgrade (2.9) to a mnemotechnic notation for the sequence \((f_n)_{n\in \mathbb {N}_0}\). We also want to define function- and measure-valued formal power series F(q; z), \(K(\mathrm {d}q;z)\).

Definition 2.1

Let \(({\mathbb {X}}, {\mathcal {X}})\) be a measurable space.

-

(a)

A (scalar) formal power series on \({\mathbb {X}}\) is a family \((f_n)_{n\in \mathbb {N}_0}\) consisting of a scalar \(f_0\in {\mathbb {C}}\) and symmetric measurable functions \(f_n:{\mathbb {X}}^n\rightarrow \mathbb {C}\).

-

(b)

A function-valued formal power series is a family \((f_n)_{n\in \mathbb {N}_0}\) of measurable maps \(f_n:{\mathbb {X}}\times {\mathbb {X}}^n\rightarrow \mathbb {C}\) such that \((q,x_1,\ldots , x_n)\mapsto f_n(q;x_1,\ldots , x_n)\) is symmetric in the \(x_j\) variables.

-

(c)

A measure-valued formal power series is a family \((k_n(\mathrm {d}q;x_1,\ldots , x_n))_{n\in \mathbb {N}_0}\) consisting of a measure \(k_0(\mathrm {d}q)\) on \({\mathbb {X}}\) and kernels \(k_n: {\mathcal {X}}\times {\mathbb {X}}^n\rightarrow \mathbb {R}_+\) such that for each \(B\in {\mathcal {X}}\), the map \(k_n(B;\cdot )\) is symmetric in the \(x_j\) variables.

Definition 2.1(b) and (c) are formulated for functions of a single variable \(q\in {\mathbb {X}}\) and nonnegative measures, they extend in a straightforward way to functions of several variables or complex measures. Standard operations such as sums and products are defined in “Appendix A.” The operations turn the set of scalar formal power series into an algebra that corresponds to the algebra of symmetric functions from Ruelle [31, Chapter 4.4].

Example 2.2

(Exponential). Let \(\varphi \) be a nonnegative measurable function on \(\mathbb {X}\), then the power series associated with the following exponential is

Example 2.3

(Monomials). Let \(m\in \mathbb {N}\) and \(q_1,\ldots , q_m\in {\mathbb {X}}\). Let \(\delta _{p,q}\) be the Kronecker delta, equal to 1 if \(p = q\) and 0 if \(p\ne q\). Then for every measure z on \({\mathbb {X}}\), we have

which is of the form (2.9) with \(f_n \equiv 0\) for all \(n\ne m\).

Example 2.4

(The measure \(z(\mathrm {d}q)\)). Let \(z(\mathrm {d}q)\) be a measure on \(({\mathbb {X}}, {\mathcal {X}})\). Then for all \(B\in {\mathcal {X}}\),

with kernel \(k_1(B;x)=\delta _{x}(B)\), i.e., \(k_1(\mathrm {d}q;x)\) is the Dirac measure at x. Accordingly, we may view \(z(\mathrm {d}q)\) as a measure-valued formal power series in the sense of Definition 2.1(c), with \(k_n\equiv 0\) for all \(n\ne 1\) and \(k_1(\mathrm {d}q; x) = \delta _x(\mathrm {d}q)\). The measure \(z(\mathrm {d}q)\) replaces the set of monomials \((z_i)_{i=1,\ldots , d}\) that appear naturally for power series of finitely many variables, with z(B) the analogue of \(\sum _{i\in B} z_i\).

2.3 Variational Derivatives and Extraction of Coefficients

Just as for usual power series, coefficients can be extracted by taking derivatives at the origin. In our context, the correct notion of derivative is a variational derivative defined as follows.

Definition 2.5

Let \(F(z) = f_0 + \sum _{n=1}^\infty \frac{1}{n!} \int _{{\mathbb {X}}^n} f_n(x_1,\ldots , x_n) z^n(\mathrm {d}\varvec{x})\) be a formal power series, i.e., \((f_n)_{n\in \mathbb {N}_0}\) is a family of symmetric functions as in Definition 2.1(a). The variational derivative of order k is the function-valued formal power series with coefficients

Thus,

In particular, \(f_k(q_1,\ldots , q_k;z)\) is equal to the term of order zero in the formal power series \(\frac{\delta ^k f}{\delta z^k}(\varvec{q};z)\). Below, we often use the notation

Definition 2.5 is motivated by the following formal computation. For small \(t\in \mathbb {R}\) and another measure \(\mu \) on \({\mathbb {X}}\), we have

and

2.4 Fredholm Determinant

Let \(K:{\mathbb {X}}\times {\mathbb {X}}\rightarrow \mathbb {R}\) be a kernel and \({\mathbb {K}}\) the associated integral operator in \(L^2({\mathbb {X}}, {\mathcal {X}}, z(\mathrm {d}x))\), given by

For sufficiently regular kernels K, the Fredholm determinant \(\det ( \mathrm {Id} - {\mathbb {K}})\) is

see e.g., Sect. 3.11 in [32]. The right-hand side of (2.17) is always well-defined as a formal power series in z, without any regularity assumptions on the kernel. Accordingly, we adopt (2.17) as a definition of the Fredholm determinant on the level of formal power series.

The definition is easily extended to kernels \(K_z\) and associated operators \({\mathbb {K}}_z\) that are themselves given by formal power series, as in Eq. (3.5). That is, suppose we are given a family of measurable functions \(k_0:{\mathbb {X}}\times \mathbb X\rightarrow \mathbb {R}\) and \(k_n : {{\mathbb {X}}} \times {\mathbb {X}} \times {\mathbb X}^n \rightarrow \mathbb {C}\) such that \((q,q';x_1 ,\ldots x_n) \mapsto k_n(q,q';x_1 ,\ldots x_n)\) is symmetric in the \(x_i\) variables, and define

The determinant \(\mathrm {det}\, ((K_z(q_i,q_j))_{i,j=1,\ldots ,n})\) is a combination of products of power series, the integral of formal power series is defined using (A.6). Therefore, the \(n\times n\) determinants and integrals in (2.17) stay well-defined as a formal power series with \(K_z\) instead of K. For the nth summand on the right-hand side of (2.17), the first nonzero term in the power series expansion has degree n, because of the “integration” with \(z^n(\mathrm {d}\varvec{x})\). Hence, the contributions for the term of degree \(m \in \mathbb {N}\) in the formal power series of \(K_z\) comes from summands on the right-hand side for \(n \le m\). Therefore, the coefficient of the degree m is a finite sum of finite products of the functions \(k_n\), and hence the infinite series on the right-hand side is rigorously defined as a formal power series.

We conclude with a remark that may be helpful for readers which are not too keen on working with Fredholm determinants.

Remark 2.6

One can replace the Fredholm determinant with determinants of finite matrices. Recall from Example 2.3 how to interpret \(z(\{q\})\) as a formal power series.

Let \(n\in \mathbb {N}\) and \((q_1,\ldots ,q_n)\in {\mathbb {X}}^n\). Set \(Q=\{q_i:\, i=1,\ldots ,n\}\). Then, the nth coefficient of the Fredholm determinant \(\det (\mathrm {Id}- {\mathbb {K}}_z)\), evaluated at \((q_1,\ldots ,q_n)\), is equal to the nth coefficient at \((q_1,\ldots ,q_n)\) of the \((\#Q)\times (\#Q)\)-matrix

One can replace Q by any \(Q' \supset Q\) without altering the coefficient

If one additionally wants to avoid the use of measures for z, because one is either only interested in densities or maybe even in generalized functions, then in order to compute the nth. coefficient it is sufficient to consider the following determinant

where m is a reference measure on \(\mathbb {X}\), for example typically the Lebesgue measure.

For both cases, more details can be found at the end of “Appendix A.” The use of the Fredholm determinant gives the most natural connection to the combinatorics. All other interpretations will give rise to the same result as the coefficients of the associated formal power series are unchanged.

3 Main Results

Let \(({\mathbb {X}}, {\mathcal {X}})\) be a measurable space and

a function-valued formal power series in the sense of Definition 2.1(b). Thus, each \(A_n: {\mathbb {X}}\times \mathbb X^n\rightarrow \mathbb {C}\) is a measurable function that is symmetric in the \(x_j\)-variables. Define a measure-valued formal power series \(\rho (\mathrm {d}q;z)\) by

The coefficients of the power series on the right-hand side are defined rigorously by Eqs. (A.9) and (A.7). We would like to determine the inverse power series \(\zeta [\nu ](\mathrm {d}q)= \zeta (\mathrm {d}q;\nu )\), that is

with the composition defined by (A.13). In a previous article [23], we have proven that the inversion is always possible on the level of formal power series, and we gave sufficient conditions for the absolute convergence of the involved power series. Precisely, concerning the formal inverse, we have proven that there is a unique family of formal power series \((T_q^\circ )_{q\in {\mathbb {X}}}\) that solves the fixed point equation

compare [7, Theorem 3.2.2] for finitely many variables. Moreover, the measure-valued formal power series

(see again (A.7)) satisfies Eq. (3.3).

Further we have shown [JKT2019, Proposition 2.6] that the power series \(T_q^\circ \) is the generating function for rooted weighted trees whose root has color q and is a ghost. (It does not come with powers of z in the generating functional.) The tree formula for the inverse is recalled in detail in Sect. 4.2. Corollary 3.5 provides an alternative representation as the coefficient of another power series, generalizing the multivariate Lagrange inversion formula (2.5).

First, however, we generalize Eq. (2.4) to uncountably many colors. The determinant in Eq. (2.4) is replaced with a Fredholm determinant. Define the kernel

The variational derivative has been introduced in Definition 2.5, see also Eq. (A.4). In particular,

Consider the formal operator

which we may view as a (formal) integral operator in \(L^2(\mathbb X,{\mathcal {X}},z(\mathrm {d}q))\) with kernel \(K_z(q',q)\). The Fredholm determinant \(\mathrm {det}(\mathrm {Id} - {\mathbb {A}}_z)\) is defined, as a formal power series, as in Sect. 2.4, see also Eq. (3.9) below.

Theorem 3.1

(Lagrange-Good inversion). Let \(\rho [z](\mathrm {d}q)= z(\mathrm {d}q) \exp \bigl ( - A(q;z)\bigr )\), where A is defined in (3.1). We denote by \(\zeta [\nu ](\mathrm {d}q)\) the formal power series of the inverse of \(\rho [z](\mathrm {d}q)\). Let \(\Phi (z) = \Phi _0+ \sum _{n=1}^\infty \frac{1}{n!}\int _{{\mathbb {X}}^n} \Phi _n(\varvec{x}) z^n(\mathrm {d}\varvec{x})\) be a further formal power series.

Define a formal power series \(\Psi \) (using (A.13)) by

Then, for all \(n\in \mathbb {N}\) and \((q_1,\ldots ,q_n) \in {\mathbb {X}}^n\), \( \Psi _n(q_1,\ldots ,q_n)\) is equal to the term of order zero in the formal power series

By the definitions adopted in Sect. 2.4, the Fredholm determinant in (3.8) is given by

we will sometimes use the heuristic notation

Remark 3.2

Following Remark 2.6, the Fredholm determinant in Theorem 3.1 can be replaced by usual determinants in two ways:

-

(1)

Using restrictions, we get that

$$\begin{aligned} \det \left( \left( \delta _{qq'} - z(\{q\})\frac{\delta }{\delta z(q')} A(q;z)\right) _{q,q'\in Q}\right) , \end{aligned}$$(3.10)where

$$\begin{aligned} Q:=\{q_i \mid i =1,\ldots , n\}. \end{aligned}$$(3.11)The replacement is also possible as well if we use instead of Q any bigger set \(Q'\supset Q\).

-

(2)

If z has a density with respect to a reference measure m, which we denote also by z, or if z is a generalized function one can replace the Fredholm determinant by

$$\begin{aligned} \int _{\mathcal {X}}\mathrm {det}\left( \Bigl ( \delta (x_j - x_j) - z(x_i) \frac{\delta }{\delta z(x_j)} A(x_i;z) \Bigr )_{i,j = 1, \ldots , n}\right) m(\mathrm {d}x_1) \ldots m(\mathrm {d}x_n),\nonumber \\ \end{aligned}$$(3.12)where the expression is well-defined for nice enough A; indeed see (3.9).

The usual determinant may feel more elementary; however, the Fredholm determinant is defined as a series of usual determinants anyhow. If one wishes to apply the theorem in a functional-analytic context the Fredholm determinant may make sense as an actual determinant of an operator, while \(z(\{q\})\) in the finite matrix, could always be zero in the function space considered, for example in \(L^p\)-spaces.

Remark 3.3

We stress that the determinant in Eq. (3.10) is the determinant of a matrix indexed by a set of colors Q and not by indices \(i,j\in \{1,\ldots , n\}\). Crucially, if \(q_i = q_j\) for some \(i \ne j\), the color \(q= q_i = q_j\) gives rise to only one row and column in the matrix. As a consequence, colors may repeat among the \(q _i\)’s but the determinant still be non-zero.

This is consistent with the determinant in Eq. (2.4) for finitely many variables. In analytic proofs [20], the determinant comes in via a complex change of variables in a contour integral. In particular, every variable \(z_k\) appears only once in the determinant, even when we are interested in coefficients of monomials with powers \(n_k\ge 2\). See also Eq. (A.21).

When \(\Phi (z) =1\), we have \(\Psi _n\equiv 0\) for all \(n\ge 1\), and we obtain the following striking result.

Proposition 3.4

For all \(n\ge 1\) and \((q_1,\ldots ,q_n)\in {\mathbb {X}}^n\), the term of order zero in the formal power series

vanishes.

Note that the expression in the curly bracket also depends on n. Remark 3.2 applies here as well. These cancellations give rise to the inversion formula expressed in terms of trees as given in Sect. 4.2. Similar cancellations happen in [2] where the formal inverse is expressed as a one-point correlation function \(\rho ^{(1)}(x)\) of an appropriately chosen complex Bosonic gas. In the latter case, cycles are canceled by the partition function Z leaving one tree with root color x.

Another special case of Theorem 3.1 corresponds to the choice \(\Phi (z) = z(B)\) with \(B\subset {\mathbb {X}}\) measurable. (The analogue for finitely many variables is \(\sum _{i\in B} z_i\).)

Corollary 3.5

(Determinant formula for the inverse). For every \(B\in {\mathbb {X}}\), the nth coefficient of \(\zeta (B;\nu )\), evaluated at \((q_1,\ldots , q_n) \in {\mathbb {X}}^n\), is equal to the nth coefficient of

evaluated at \((q_1,\ldots , q_n)\).

The proposition provides an analogue for (2.5).

4 Lagrange-Good Inversion. Proof of Theorem 3.1

4.1 Enriched Maps, Cycle-Rooted Trees, Weights

A key ingredient of the bijective proofs by Labelle and Gessel [17, 27] is a graphical representation of mappings. Let us briefly recall some standard vocabulary, following [7, Chapters 3.1 and 3.2]. Let V, S be disjoint finite set.

A partial endofunction on \(U:=V\cup S\) with domain V is a mapping \(f:V \rightarrow U=V \cup S\). Any partial endofunction is associated with a directed graph \(G=(U,E)\), or digraph for short, with vertex set U and directed edges \(E = \{ (v,f(v))\mid v\in U \}\subset U\times U\). The digraph G may have self-edges (v, v), called loops. Loops in G correspond to fixed points of the mapping, \(f(v) =v\). The graphs G obtained in this way have two types of vertices: Vertices \(v\in V\) have exactly one outgoing edge because f maps v to exactly one vertex f(v). Vertices \(v\in U\setminus V=S\) are sinks, i.e., they have no outgoing edge, because they do not belong to the domain of f.

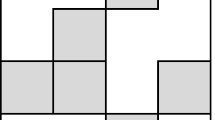

In both cases the out-degree in G of every vertex is either 0 or 1. We call digraphs with this property functional digraphs. Clearly there is a one-to-one correspondence between functional digraphs G and partial endofunctions f and we often identify them, cf. Fig. 1.

In order to take into account the exponential \(\exp ( A(q;z))\) in our formulas, we enrich partial endofunctions with an additional structure: To each element \(v\in V \cup S\), we add a set partition \( P_v\) of the elements of the preimage \(f^{-1}(\{v\})\) (the preimage is often called fiber of v). This is a special case of the R-enriched structures often used in combinatorial proofs of Lagrange inversion formula [7, Definitions 3.1.1 and 3.1.8]. It is customary to represent R-structure as a structure on the incoming edges of the functional digraph; in our case, \( P_v\) is represented as a set partition of the incoming edges (w, v).

Definition 4.1

Let V and S be finite possibly empty disjoint sets. If V is empty, we set \(\mathcal {M}^S[V] = \mathcal {M}^S[\varnothing ] := \varnothing \). If V is non-empty, we define \(\mathcal {M}^S[V]\) to be the collection of pairs \({\bar{f}} = (f, (P_v)_{v\in V\cup S})\) such that

-

f is a map \(f:V\rightarrow V\cup S\).

-

For each \(v\in V\cup S\), \(P_v\) is a partition into non-empty sets of the preimage \(f^{-1}(\{v\})\). If the preimage is empty we set \(P_v = \varnothing \).

An element \({\bar{f}}= (f,( P_v)_{v\in V\cup S}) \in {\mathcal {M}}^S[V]\) is called enriched partial endofunction on \(V\cup S\), with domain V and sink set S, or enriched map for short.

Digraph of a typical enriched partial endofunction \({\mathcal {M}}^S[V]\) containing vertex-rooted trees and cycle-rooted trees. The vertices from V are depicted as black filled circles, whereas the sinks S are depicted as unfilled circles. The small lines crossing the edges of the graph represent the blocks W of the partitions \(P_v\). For more details cf. Fig. 3

For a typical element of \(\mathcal {M}^S[V]\) see Fig. 2. To lighten notation, if \(S= \varnothing \), we drop the superscript S and write \({\mathcal {M}}[V]\). If \(S = \{\circ \}\) is a singleton, we drop the braces in the notation and write \(\mathcal M^\circ [V]\) instead of \(\mathcal {M}^{\{\circ \}}[V]\).

A digraph G is connected if any two distinct vertices v, w can be connected by a path from v to w or from w to v. The connected components of functional digraphs are of two types: trees and cycle-rooted trees, by which we mean the following.

Definition 4.2

Let \(G= (V\cup S, E)\) be a functional digraph with domain V, that is a directed graph such that every vertex \(v\in V\) has out-degree 1 and every vertex \(w\in S\) has out-degree zero.

-

(a)

A cycle in G is a sequence \(v_1,\ldots , v_n\) in V such that \((v_i,v_{i+1})\in E\) for all \(i\in \{1,\ldots , n-1\}\) and \((v_n,v_1) \in E\). This includes loops (\(n=1\)).

-

(b)

G is a vertex-rooted tree if it is connected and it has no cycle. Then, S is necessarily a singleton \( =\{\circ \}\), the root is the unique sink \(\circ \).

-

(c)

G is a cycle-rooted tree if it is connected and it has exactly one cycle. Then, S must be empty.The unique cycle in G is called the root cycle of G.

By some abuse of language, an enriched map or graph are called vertex-rooted or cycle-rooted tree if the underlying graph G is vertex- or cycle-rooted tree, respectively. The class of enriched maps \({\bar{f}}\in {\mathcal {M}}^\circ [V]\) that are vertex-rooted trees is denoted \(\mathcal {T}^\circ (V)\).

Finally, we define weights of enriched maps. For \({\bar{f}} = (f,(P_v)_{v\in V\cup S})\in {\mathcal {M}}^S[V]\) and \(\varvec{x}\in \mathbb X^{V\cup S}\), the weight of \({\bar{f}}\), given the coloring \(\varvec{x}\), is

We denote for short \( {\varvec{x}}_W:=(x_w)_{w\in W}\). For a graphical representation, see Fig. 3.

The weight (4.1) of an enriched digraph is a product of contributions of building blocks. The left panel represents an enriched digraph with weight \(A_{3}(x_0 ; x_1, x_2 ,x_3) A_{2}(x_0 ; x_4, x_5) A_{1}(x_0 ; x_6)A_{2}(x_4 ; x_7, x_8) A_{1}(x_4 ; x_{10}) A_{2}(x_5 ; x_{11}, x_{12}) A_{1}(x_5 ; x_{13}).\) The right panel separates the graph into the single building blocks, each of which corresponds to a factor \(A_{\#W}(x_v ; (x_w)_{w \in W})\) in the graph weight. The partitions are given by \(W_1 = \{ 1,2,3\}\), \(W_2=\{ 4, 5 \}\), \(W_3 =\{ 6 \}\), \(W_4=\{ 7,8,9\}\), \(W_5 = \{ 10\}\), \(W_6=\{ 11, 12\}\), \(W_7 = \{13\}\) and the partitions are \(P_0 = \{ W_1 ,W_2 ,W_3\}\), \(P_4 = \{ W_4, W_5 \}\), and \(P_5 = \{ W_6, W_7 \}\)

4.2 The Tree Formula for the Inverse Power Series

For our further calculation, we need a combinatorial expression for the inverse power series. Such a representation can be obtained directly without using Lagrange-Good type formulas. We briefly recall the tree formula for the inverse power series proven in [23]. Let

and

Lemma 4.3

The family \((T_q^\circ (\nu ))_{q\in {\mathbb {X}}}\) fulfills the following functional equation as formal power series

For finite spaces \({\mathbb {X}}\), the lemma follows from Theorem 2 in Chapter 3.2 on implicit species in the book by Bergeron, Labelle, and Leroux [7].

Proof

The lemma follows from [23, Lemma 2.1 and Proposition 2.6], we give a self-contained proof for the reader’s convenience. Calling \(\{V_1, \ldots , V_m\}\) the partition \(P_\circ \) of the vertices incident to the root \(\circ \), we can rewrite \(t_n\) using the tree structure of the associated graph as

where we defined:

(Compare with the calculations (formulas (26)-(28)) in the proof of Theorem 1 in [2]].) Note that according to (A.2) the expression \(B(q;V_i)\) is the \(\# V_i\)th. coefficient in powers of \(\nu \) of

According to (A.9), the right-hand side of (4.5) is the nth coefficient of the exponential of (4.7). \(\square \)

When dealing with generating functions of rooted trees we have two choices, either look at trees rooted in a ghost or trees rooted in a labeled vertex. In the univariate case (no colors), these give rise to two different generating functions \(T^\circ (\nu )\) and \(T^\bullet (\nu )\) related by \(T^\bullet (\nu )= \nu T^\circ (\nu )\). The multivariate case (finitely many colors) gives rise to a relation of the type \( T_i^\bullet (\nu )= \nu _i T^\circ _i(\varvec{\nu }) \), with i the color of the root. This last relation should remind the reader of the relation \( \zeta (\mathrm {d}q;\nu ) = \nu (\mathrm {d}q) T_q^\circ (\nu ) \) used to define \(\zeta (\mathrm {d}q;\nu )\) in (3.4). As a consequence, we should expect that the measure-valued series \(\zeta (\mathrm {d}q;\nu )\) corresponds to rooted trees with the root integrated over.

The next lemma makes this statement precise. It says that the series \(\zeta (B;\nu )\) is given by a sum over rooted trees with root color in B.

Lemma 4.4

Let \(\zeta (\mathrm {d}q;z) = T_q^\circ (q;z) z(\mathrm {d}q)\). The nth coefficient of \(\zeta (B;\nu )\), evaluated at \((q_1,\ldots , q_n)\), is equal to

and the term of order zero vanishes, \(\zeta _0(B) =0\).

Proof

The lemma is an immediate consequence of the definition (3.4) of \(\zeta (\mathrm {d}q;\nu )\) and Eq. (A.7). \(\square \)

Theorem 4.5

For \(\rho \) given in (2.1) we have \((\zeta \circ \rho )(\mathrm {d}q;z) = z(\mathrm {d}q)\) and \( (\rho \circ \zeta )(\mathrm {d}q;\nu ) = \nu (\mathrm {d}q)\) as an equality of measure-valued formal power series, with the composition defined in (A.13).

Proof

(Proof sketch) By the definition of \(\rho (\mathrm {d}q; z) = \exp (-A(q;z)) z(\mathrm {d}q)\) and Lemma 4.3, we have

The previous chain of equalities is formal but it can be rigorously justified by properties of operations on formal power series (e.g., associativity of the product), defined in terms of coefficients only; we leave the details to the reader. The equality \((\zeta \circ \rho )(\mathrm {d}q;z) = z(\mathrm {d}q)\) is proven by a similar argument and another fixed point equation, see [23, Lemma 2.12]. \(\square \)

4.3 Cycle-Rooted Forests. Proof of Proposition 3.4

For the proof of Proposition 3.4, we relate the right-hand side of Eq. (3.13) to a sum over cycle-rooted forests and look for combinatorial cancellations. We start with the exponential. Let \(E_k^n(\varvec{q};\varvec{x})\) be the coefficients of the exponential appearing in Proposition 3.4, i.e.,

Figure 2 depicts a forest of vertex-rooted and cycle-rooted trees. The vertices \([n]\setminus I\) are represented as white.

Lemma 4.6

Let \(E^n_k\) be as in (4.10). For \(n\in \mathbb {N}\), \(\varvec{q}\in {\mathbb {X}}^n\), and \(I\subset [n]\), we have

Notice that Lemma 4.6 does not address general coefficients \(E^n_{\#I}(q_1,\ldots , q_n;(x_i)_{i\in I})\), but only the special case \(x_i = q_i\). Roughly, \(E_{\#I}^n(q_1,\ldots , q_n; (x_i)_{i\in I})\) is a sum over enriched maps from I to \(\{1,\ldots , n\}\), but if \(x_i \ne q_i\) there are color-conflicts and the color-dependent weight of a map is inappropriate to give a representation.

Proof

By \(\exp \left( \sum _{i=1}^n A(q_i;z)\right) = \prod _{i=1}^n \exp \left( A(q_i;z)\right) \) and (A.3), we can write for all \(\varvec{x}\in {\mathbb {X}}^I\)

where \(I_1,\ldots ,I_n\) are pairwise disjoint subsets, with \(I_k = \varnothing \) allowed, whose union is I and \({\varvec{x}}_I = (x_i)_{i \in I}\). By (A.8), we have that:

where \(\mathcal {P}(I_k)\) is the collection of set partitions \(\{W_1,\ldots ,W_r\}\) of \(I_k\) into non-empty sets \(W_i\). Combining the two, we obtain that

Each n-tuple \((I_1,\ldots ,I_n)\) gives rise to a map \(f:I\rightarrow [n]\) by defining \(f^{-1}(\{k\}) = I_k\); the correspondence is clearly one-to-one. Considering \({\bar{f}} = \left( f , (P_k)_{k \in [n]} \right) \) and \(\varvec{x}_I=\varvec{q}_I\) we recognize the weight \(w(\bar{f},\varvec{q})\) and obtain (4.11). \(\square \)

Next, we turn to the determinant on the right-hand side of Eq. (3.13). Write

where \( Q= \{q_i\mid i=1,\ldots , n\}\) is defined as in (3.11). We start with the interpretation of the left-hand side as a formal power series, cf. (3.9),

and next we use the combinatorial interpretation of the matrix element

which by Eq. (3.5) takes the form

In \(M_{p,p'}(z)\), we recognize the generating function for digraphs G with vertices \(\circ , \circ '\), \(1,\ldots , k\) that have edges \((\circ , \circ ')\) and \((\circ , j)\), \(j = 1, \ldots k\). The vertex \(\circ \) has color p, the vertex \(\circ '\) color \(p'\), and j the color \(x_j\).

We call such a digraph with the associated coloring a spike of type \((p,p')\) and the edge \((\circ , \circ ')\) the base edge of the spike. A spike with base edge \((\circ , \circ ')\) is identified with the enriched graph \({\bar{G}}\) that has the trivial partition consisting of a single block, \( P_{\circ } = \{\circ ', \varvec{x}_{[k]} \} \). See the left panel of Fig. 4 for an example of a spike.

Concatenating base edges of spikes in a circular fashion gives rise to an object consisting of a base cycle and additional incoming edges.

Definition 4.7

Let V be a finite non-empty set and \({\bar{f}} = (f,(P_v)_{v\in V}) \in \mathcal {M}[V]\). We call \({\bar{f}}\) a crown if there exists a finite set \(B\subset V\) (the base of the crown) such that:

-

\(f(V) = B\),

-

f restricted to B is a cycle,

-

for all \(r\in B\), \(P_r = \{f^{-1}(\{r\})\}\), that is, the partition \(P_r\) consists of a single block.

Let \(\mathcal {K}[V]\) be the collection of crowns on V.

The right panel in Fig. 4 shows are crown. The simplest crown is a loop.

Left panel shows a spike with \(k=4\). The right panel shows a crown, where the set of white vertices the base B and V (as in Definition 4.7) is the set of all white and black vertices. The partitions \(P_r\) are symbolized by the small curved lines crossing the edges

The next lemma expresses the relevant coefficient of the determinant as a sum over assemblies of crowns, with an additional factor \((-1)^s\) where s is the number of crowns. The factor \((-1)^s\) is a crucial ingredient to cancellations in the proof of Proposition 3.4.

Lemma 4.8

Let \(D_k\) be as in (4.15). Then,

where the sum is over set partitions \(\{V_1,\ldots ,V_s\}\) of [k].

Proof

Using the definition as formal power series (3.9), we see that the mth coefficient of the determinant is

The definition of the determinant gives

which we may also write as

with \(s(\sigma )\) the number of cycles in the cycle decomposition of the permutation \(\sigma \). Indeed, let \(\sigma =\sigma _1\cdots \sigma _s\) be the cycle decomposition into s cycles of respective lengths \(\ell (\sigma _i)\). Then, \(\sum _{i=1}^s \ell (\sigma _i)=m\) and

The sum in (4.22) is a sum over the following directed graphs. Each connected component is a cycle (or loop). Each edge \((p_1,p_2)\) contributes a factor \(M_{p_1,p_2}\) and the sign is \(-1\) to the numbers of cycles. By the definition (A.2) of the product of power series, the nth coefficient of (4.22) at \((x_1,\ldots , x_n)\) is

The sum is over ordered set partitions \((J_1,\ldots , J_m)\) of [n] into m sets. Because of \(A_0=0\), only non-empty sets \(J_i \ne \varnothing \) contribute.

The expression (4.24) is a sum over permutations \(\sigma \in {\mathfrak {S}}_m\) and sequences \((G_1,\ldots , G_m)\) of spikes with vertex sets \(\{\circ _i \} \cup J_i\) with disjoint \(J_i\)’s and base edge \((\circ _{\sigma (i)}, \circ _{i})\). Such a sequence is naturally associated with the digraph G with vertices \(\{1,\ldots , n\} \cup \{ \circ _1 , \ldots , \circ _m\}\). Each connected component of G is a crown, the base of the crown consists only out of vertices from \(\{ \circ _1 , \ldots , \circ _m\}\) and all vertices not in the base are from \(\{1,\ldots , n\}\). The base of the crown corresponds to a cycle in \(\sigma \). The mapping \((\sigma , (G_1,\ldots , G_m))\mapsto G\) induces a one-to-one correspondence between (i) pairs \((\sigma , (G_1,\ldots , G_m))\) and (ii) collections of crowns with the vertices in the bases of the crown are the vertices \(\{ \circ _1 , \ldots , \circ _m\}\) and all of them are in some base of a crown.

Hence, the nth coefficient of (4.20) is given by

where the primed sum is over enriched endofunctions on [k] whose connected components are crowns. The next step is to drop the distinction betweed \(\varvec{p}\) and \(\varvec{x}\), which gives rise to a binomial coefficient \(\left( {\begin{array}{c}n+m\\ m\end{array}}\right) \) which cancels with the factorial pre-factors, that is 1/m! in (3.9), 1/n! from (3.5) and \(k!=(n+m)!\) from (4.15). The kth coefficient of \(\det (\mathrm {id} - M(z))\) is therefore equal to

\(\square \)

Proof of Proposition 3.4

Let \(E_k^n\) and \(D_k\) be the coefficients of the exponential and determinant as in (4.10) and (4.15). By (A.2), the power series in braces in Proposition 3.4 has as kth coefficient

In view of (A.4), we have to show, in order to prove Proposition 3.4, that

Note that \(\varvec{x}_I\) is replaced by \(\varvec{q}_I\) and k has to be equal to n. Hence, the list \(\varvec{q}_I\) is a part of \(\varvec{q}\).

By Lemmas 4.6 and 4.8 , the left-hand side of (4.27) is given by

In words, a sum over collections of crowns \({\bar{g}}_1,\ldots ,\bar{g}_r\) with disjoint supports \(V_1,\ldots , V_r\) and a forest \({\bar{f}}\) of cycle-rooted trees with root cycle in \(I\subset [n]\setminus \cup _k V_k\) and vertex-rooted trees with root vertices in \(\cup V_k\). Each such tuple can be mapped to a map \({\bar{F}}\in \mathcal {M}[n]\). The relation between weights is

The mapping \(({\bar{f}},{\bar{g}}_1,\ldots , {\bar{g}}_r)\mapsto {\bar{F}}\) is surjective but not injective: each \({\bar{F}}\in \mathcal {M}[n]\) is a forest of cycle-rooted trees (no vertex-rooted tree). Each such cycle-rooted tree can decide whether (a) it belongs to the forest \({\bar{f}}\), or (b) it is split into a crown \({\bar{g}}\) and attached vertex-rooted trees. Note that the set of splitting points is uniquely determined. The two choices for a given \({\bar{F}}\) come with opposite signs and sum to zero. \(\square \)

4.4 Forests with Several Sinks. Proof of Theorem 3.1

The proof of Theorem 3.1 builds on the cancellations from Proposition 3.4. The directed graphs in the proof of Proposition 3.4 consists of crowns and vertex-rooted trees which can be combined in such a way that all connected components are cycle-rooted trees. In contrast, for Theorem 3.1, the graphs consist of crowns and two types of vertex-rooted trees. The first type is as in Proposition 3.4, the second one is related to the coefficients of the power series of \(\Phi \). As in Proposition 3.4, the cycle-rooted trees cancel exactly with the first type of vertex-rooted trees and only the second type of trees survives, which is a combinatorical justification that the inversion is related to vertex-rooted trees only.

Let us introduce a shorthand for a forest of trees

where is the sum is over ordered partitions \((V_\ell )_{\ell \in L}\) of \([n]\setminus L\), with \(V_\ell = \varnothing \) allowed.

Lemma 4.9

Let \(n\in \mathbb {N}\) and \((q_1,\ldots , q_n) \in {\mathbb {X}}^n\). Fix \(L\subset [n]\) and consider sums over pairs \(I,J \subset [n]\) such that [n] is the disjoint union of L, I, and J. Then,

where \(I_1\), \(I_2\) are disjoint subsets of I such that \(I_1 \cup I_2 =I\) (the sets \(I_1, I_2\) could also be empty).

Proof

By Lemma 4.6 we have that

Define \(I_1\) as the union of all the vertices in I from connected components which are vertex rooted trees with root vertex in L. Then, \(I_2\) is the set of all vertices in I associated with root vertices in J. This correspondence is one to one. \(\square \)

Proof of Theorem 3.1

By the product formula (A.3), the nth coefficient of

at \((q_1,\ldots , q_n)\) is

where the sum is over ordered partitions L, I, J of [n] with empty sets allowed. By definition (3.4) of \(\zeta (\mathrm {d}q;\nu )\) and definition (A.10) of the composition, the nth coefficient of \(\Psi (\nu ) = \Phi (\zeta (\nu ))\) is

where the sum is over ordered partitions \((V_\ell )_{\ell \in L}\) of \([n]\setminus L\), with \(V_\ell =\varnothing \) allowed. So we have to show that the expressions (4.34) and (4.35) are equal. Indeed, by Lemma 4.9, we have that

Using that \(L, J, I_1, I_2\) are disjoint with union [n], we obtain that

Using the cancelations from Proposition 3.4 (most easily in the form (4.27)) we get that

where L and \(I_2\) are disjoint with union [n]. This is exactly (4.35). \(\square \)

5 Discussion

In this final section, we discuss connections to similar methods in different contexts. Some occurrences of trees in various areas of mathematics are listed in Table 1.

5.1 Gallavotti Trees

For simplicity, let us consider a gas consisting of classical particles interacting via a two-body potential V at inverse temperature \(\beta \). From basic statistical mechanics, we can write the density \(\rho \) as a function of the activity z as follows:

where \(b_n\) are the Mayer coefficients related to the pair potential V. We observe that one can invert the above expression following different strategies, we present a few. From (5.1), solving for z, we have:

By iterating over z and expanding the powers of the sums one obtains terms either with \(\rho (z)\) or with z in which case we keep expanding. It is easy to visualize this procedure; each iteration is a branching of a tree and each vertex of the children either has a \(\rho (z)\) (and we stop) or it has a z and we continue to the next generation. Hence, overall this expansion can be viewed as a power series ,in \(\rho (z)\) with the power representing the number of final points. This construction can be also found in in the Main Theorem 3 in [34] and in [6], see also the survey [35]. We note that this method of inverting power series has been already used in statistical mechanics, it is actually reminiscent of Gallavotti’s approach to express the Lindstedt perturbation series in the context of KAM theory [16].

We observe that in the above example trees are generated by iterating the mapping \(z\mapsto \rho -\sum _{n\ge 2} n b_n z^n\) and they provide a power series representation of the fixed point solution of the mapping. We notice that other mappings can be suggested and, as it is usually the case, they correspond to more or less efficient methods. More precisely, some alternative mappings are

and

for some coefficients \(a_n\). In [23] we demonstrated, cf. Theorem 4.1, that (5.4) has a much better radius of convergence at least in some regimes.

5.2 Abdesselam’s Approach

In [3], A. Abdesselam presents an alternative proof of Lagrange-Good multivariable inversion formula using a quantum field theory (QFT) model. Details are given in the companion papers [1] and [2]. This reveals an interesting connection between QFT calculations and Gessel’s combinatorial proof [17], and seems to show a similar kind of cancellations. One ingredient of Abdesselam’s proof is a representation of the one-point correlation function of some complex bosonic field as a sum over trees, which connects to the representation of the inverse in terms of trees. Another ingredient is a graphical representation of a calculus of formal power series, coming with an algebraic formalization of Feynman diagrams [1].

5.3 Other Connections

Tree expansions is a favorite topic in several areas of mathematics. Without pretending of being exhaustive, we note Butcher series in computing higher order Runge–Kutta methods [9, 14] and the combinatorial structure in indexing Hepp sectors in renormalization and regularity structures [22]. A common feature is that they provide a power series representation of the solution of a fixed point problem and as such we believe expansion methods of this type can be widely used in applications. The techniques developed in this paper can be used to extend these expansion in an infinite dimensional context, for example in an inhomogeneous situation as in this paper.

Notes

The choice of letters \(\rho _i\) and \(z_i\) as well as the exponential form of the map are motivated by applications in statistical mechanics [26], where the \(z_i\)’s and \(\rho _i\)’s correspond to activity and density variables and the index i may refer to the type of a particle or a discrete set of locations on a lattice. The exponential form in Eq. (2.1) will be crucial in the following.

References

Abdesselam, A.: Feynman diagrams in algebraic combinatorics. Séminaire Lotharingien de Combinatoire 49, B49c (2003)

Abdesselam, A.: The Jacobian conjecture as a problem of perturbative quantum field theory. Ann. Henri Poincaré 4(2), 199–215 (2003)

Abdesselam, A.: A physicist’s proof of the Lagrange-Good multivariable inversion formula. J. Phys. A 36(36), 9471–9477 (2003)

Barnabei, M.: Lagrange inversion in infinitely many variables. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 108(1), 198–210 (1985)

Bousquet, M., Chauve, C., Labelle, G., Leroux, P.: Two bijective proofs for the arborescent form of the Good-Lagrange formula and some applications to colored rooted trees and cacti. Theor. Comput. Sci. 307(2), 277–302 (2003)

Bass, H., Connell, E .H., Wright, D.: The Jacobian conjecture: reduction of degree and formal expansion of the inverse. Bull. Am. Math. Soc. (N.S.) 7(2), 287–330 (1982)

Bergeron, F., Labelle, G., Leroux, P.: Combinatorial Species and Tree-Like Structures. Encyclopedia of Mathematics and Its Applications, vol. 67. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (1998)

Bender, E. A., Richmond, L. B.: A multivariate Lagrange inversion formula for asymptotic calculations. Electron. J. Combin. 5, Research Paper 33 (1998)

Butcher, J.C.: An algebraic theory of integration methods. Math. Comp. 26, 79–106 (1972)

Ehrenborg, R., Méndez, M.: A bijective proof of infinite variated Good’s inversion. Adv. Math. 103(2), 221–259 (1994)

Faris, W.G.: Combinatorial species and Feynman diagrams, Sém. Lothar. Combin. 61A (2009/11), Art. B61An

Faris, W.G.: Combinatorial species and cluster expansions. Mosc. Math. J. 10(4), 713–727, 839 (2010)

Faris, W.G.: Combinatorics and cluster expansions. Prob. Surv. 7, 157–206 (2010)

Faris, W.G.: Rooted tree graphs and the Butcher group: combinatorics of elementary perturbation theory, Sojourns in Probability and Statistical Physics - II: Brownian Web and Percolation, A Festschrift for Charles M. Newman (V. Sidoravicius, ed.), Springer Proceedings in Mathematics & Statistics, vol. 299, pp. 135–166. Springer Nature, Singapore (2019)

Flajolet, P., Sedgewick, R.: Analytic Combinatorics. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (2009)

Gallavotti, G.: Perturbation Theory, Mathematics of Complexity and Dynamical Systems, Vols. 1–3, pp. 1290–1300. Springer, New York (2012)

Gessel, I.M.: A combinatorial proof of the multivariable Lagrange inversion formula. J. Combin. Theory Ser. A 45(2), 178–195 (1987)

Gessel, I.M.: Lagrange inversion. J. Combin. Theory Ser. A 144, 212–249 (2016)

Goulden, I.P., Kulkarni, D.M.: Multivariable Lagrange inversion, Gessel-Viennot cancellation, and the matrix tree theorem. J. Combin. Theory Ser. A 80(2), 295–308 (1997)

Good, I.J.: Generalizations to several variables of Lagrange’s expansion, with applications to stochastic processes. Proc. Camb, Philos. Soc. 56, 367–380 (1960)

Good, I.J.: The generalization of Lagrange’s expansion and the enumeration of trees. Proc. Camb. Philos. Soc. 61, 499–517 (1965)

Hairer, M.: An analyst’s take on the BPHZ theorem, Computation and combinatorics in dynamics, stochastics and control, Abel Symp., vol. 13, pp. 429–476. Springer, Cham (2018)

Jansen, S., Kuna, T., Tsagkarogiannis, D.: Virial inversion and density functionals. Online preprint arXiv:1906.02322 [math-ph] (2019)

Joyal, A.: Une théorie combinatoire des séries formelles. Adv. Math. 42(1), 1–82 (1981)

Johnson, S.G., Prochno, S.: Faà di Bruno’s formula and inversion of power series. Online preprint arXiv:1911.07458 [math.CO] (2019)

Jansen, S., Tate, S.J., Tsagkarogiannis, D., Ueltschi, D.: Multispecies virial expansions. Commun. Math. Phys. 330(2), 801–817 (2014)

Labelle, G.: Une nouvelle démonstration combinatoire des formules d’inversion de Lagrange. Adv. Math. 42(3), 217–247 (1981)

Méndez, M., Nava, O.: Colored species, \(c\)-monoids, and plethysm. I. J. Combin. Theory Ser. A 64(1), 102–129 (1993)

Percus, J.K.: A note on extension of the Lagrange inversion formula. Commun. Pure Appl. Math. 17, 137–146 (1964)

Pitman, J.: Combinatorial Stochastic Processes. Lecture Notes in Mathematics, vol. 1875. Springer, Berlin (2006)

Ruelle, D.: Statistical Mechanics: Rigorous Results. World Scientific, Singapore (1969)

Simon, B.: Operator Theory, A Comprehensive Course in Analysis, Part 4. American Mathematical Society, Providence (2015)

Stell, G.: Cluster expansions for classical systems in equilibrium. In: Frisch, H.L., Lebowitz, J.L. (eds.) The Equilibrium Theory of Classical Fluids, pp. 171–261. Benjamin, New York (1964)

Wright, D.: The tree formulas for reversion of power series. J. Pure Appl. Algebra 57(2), 191–211 (1989)

Wright, D.: Reversion, trees, and the Jacobian conjecture, Combinatorial and computational algebra (Hong Kong, 1999), Contemp. Math., vol. 264, pp. 249–267 . Amer. Math. Soc., Providence (2000)

Acknowledgements

S.J. thanks the GSSI, T.K. the University in L’Aquila, Italy, and D.T. thanks the LMU in Munich, Germany, for hospitality. S.J. was supported by the Munich Center for Quantum Science and Technology (MCQST). We thank Abdelmalek Abdesselam, Giovanni Gallavotti, and Alessandro Giuliani for fruitful discussions and Nils Berglund for pointing out the reference [22].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Communicated by Christian Maes.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix A: Formal Power Series

Here, we describe some operations on formal power series as introduced in Definition 2.1, e.g.,

where \(({\mathbb {X}},\mathcal {X})\) is a measurable space z is a measure on \(({\mathbb {X}},{\mathcal {X}})\), and \(K_0\in \mathbb {C}\) is a scalar, and \(K_n:{\mathbb {X}} ^n \rightarrow \mathbb {C}\) are measurable maps that are invariant under permutation of the arguments. Operations are defined purely in terms of the sequence of coefficients.

Product. Let K, G be formal power series, then KG is defined by

For a motivation of this definition, see e.g., [23, Appendix A]. The empty set \(J=\varnothing \) is explicitly allowed. As an operation on sequences of symmetric functions, this is exactly the convolution in [31, Chapter 4.4]. It is not difficult to check that the product is commutative and associative. Eq. (A.2) generalizes to products \(K^{(1)}\cdots K^{(r)}\) as

where the sum runs over ordered partitions \((V_1,\ldots , V_r)\) of [n] into r disjoint parts, with \(V_i=\varnothing \) explicitly allowed.

Variational derivative. For \(q\in {\mathbb {X}}\) and K a formal power series over \({\mathbb {X}}\), we define

For higher-order variational derivatives, see Definition 2.5.

Integrals. Measures \(K(\mathrm {d}q;z) = F(q;z) z(\mathrm {d}q)\). Let F(q; z) be a function-valued power series. The power series

is defined as the power series with coefficients \(I_0:=0\) and

The definition is motivated by the following formal computation:

We also define the measure-valued formal power series \(K(\mathrm {d}q;z) = z(\mathrm {d}q) F(q;z)\) as the power series with coefficients \(K_0:=0\) and

Composition I and exponential series. Let \(F(t) = \sum _{n=0}^\infty f_n t^n/n!\) be a formal power series in a single variable t and K a formal power series on \(({\mathbb {X}},\mathcal X)\) with \(K_0=0\). The formal power series \(F\circ K\) on \({\mathbb {X}}\) is defined by \((F\circ K)_0:=f_0\) and for \(n\ge 1\),

with \({\mathcal {P}}_n\) the collection of set partitions of \(\{1,\ldots ,n\}\). Note that only because \(K_0=0\) the expression (A.8) is well-defined as a formal power series, because only in this case the sum is finite. An important special case is \(F(t) = \exp (t)\), for which Eq. (A.8) becomes

which is exactly the exponential on the algebra of symmetric functions from [31, Chapter 4.4]. For a motivation of this definition, see again, e.g., [23, Appendix A].

Composition II. In order to define the compositions in (3.3), we need a more general type of composition. Let G be a formal power series on \({\mathbb {X}}\) and F(q; z) a function-valued power series

Let \(K(\mathrm {d}q;z)\) be the measure-valued formal power series \(K(\mathrm {d}q;z) = F(q;z)z(\mathrm {d}q)\) with coefficients (A.7). The composition \(H(z):= (G\circ K)(z)\) is defined as the power series with coefficients \(H_0=0\) and for \(n\ge 1\),

The summation is over partitions \((V_j)_{j\in J}\) of \([n]\setminus J\) with empty sets \(V_j = \varnothing \) allowed. Note that the sum is only over finitely many summands and hence well-defined as a formal power series. The definition is motivated by the following formal computation:

We group terms with the same sum \(n= m+ n_1+\cdots + n_m\), write

and note that the multinomial counts the number of ways to partition [n] into sets J and \((V_j)_{j\in J}\) in such a way that \(\#J = m\) and \(\#V_j = n_j\). Exploiting the symmetry of the integrands, we arrive at

with \(H_n\) defined in (A.10).

Composition of two measure-valued series. The composition (A.10) easily extends to the composition of a measure-valued formal power series \(\Gamma \) with a formal power series of the form \(K(\mathrm {d}q;z) = F(q;z) z(\mathrm {d}q)\), for which we have defined the coefficients in Eq. (A.7).

Then, \(H= \Gamma \circ K\) is the measure-valued series which has by Eq. (A.10) the coefficients for \(n\ge 1\) and \(B\subset {\mathbb {X}}\),

In treating the the compositions \(\rho \circ \zeta \) and \(\zeta \circ \rho \) in Eq. (3.3), we need to consider \(\Gamma \) which are of the form \( \Gamma (\mathrm {d}q;z) = G(q;z) z(\mathrm {d}q)\) for some function valued formal power series G, that is by Eq. (A.7) again

Then, also H is of the form \(H(\mathrm {d}q;z) = J(q;z) z(\mathrm {d}q)\), where J is a function valued formal power series and as above,

with \( H_0 =0\). Then, using Eq. (A.7), we can directly express

This also implies that

Restriction of power series Let \(\mathbb {Y} \subset \mathbb {X}\), then one can define a restriction of the formal power series to the set \(\mathbb {Y}\), denoted by \(K\!\!\upharpoonright _{ \mathbb {Y}}\), in the following way: restrict the coefficients of K to \(\mathbb {Y}\), that is, consider

One can consider \(K_n\upharpoonright _{ \mathbb {Y}} \) also as a function on \(\mathbb {X}^n\) by defining \(K_n\upharpoonright _{ \mathbb {Y}} =0\) outside of \(\mathbb {Y}^n\) and hence we may formally write

In case that the formal power series is an actual convergent power series, the above restriction corresponds to restricting the function \( z \mapsto K(z)\) to all measures which are zero outside of \(\mathbb {Y}\). In particular, when \(\mathbb {Y}\) contains only finitely many elements, then any measure zero outside of \(\mathbb {Y}\) is of the form \(z(\mathrm {d}x) = \sum _{y \in \mathbb {Y}} z_y\delta _{y}(\mathrm {d}x)\) for some \( z_y \in \mathbb {R}_+\) and hence, in this case, \(K\upharpoonright _{ \mathbb {Y}} \) can be seen as a function on \(\mathbb {C}^{\# \mathbb {Y}}\). The analogous construction works also for \(\mathbb {Y}\) with countable many elements, but not for uncountable many elements.

In order to compute the nth. coefficient of K evaluated at \(q_1, \ldots , q_n \in \mathbb {X}\), that is \(K_n(q_1,\ldots ,q_n)\), it is sufficient to consider \(K\upharpoonright _{ Q}\), where \(Q=\{q_i:\, i=1,\ldots ,n\}\) is the set of colors in \(q_1, \ldots , q_n\). Notice that the set of colors Q has cardinality smaller than n if colors are repeated in the vector, i.e., \(q_i = q_j\) for some \(i\ne j\). The relation between the coefficients is the following

where \(\varvec{z} := ( z_q)_{q\in Q}\), \(\varvec{n} := (n_q)_{q \in Q}\), and \(n_q:= \# \{ i \in \{ 1, \ldots , n \} \, : \, q_i =q \}\), that is the number of repetitions of the color \(q_i\).

This allows us to reduce the computation of the Fredholm determinant, which appears in Theorem 3.1, to the computation of usual determinants

Lemma A.1

Let \(n\in \mathbb {N}\) and \((q_1,\ldots ,q_n)\in {\mathbb {X}}^n\). Set \(Q=\{q_i:\, i=1,\ldots ,n\}\). Then the nth coefficient of the Fredholm determinant \(\det (\mathrm {Id}- {\mathbb {K}}_z)\), evaluated at \((q_1,\ldots ,q_n)\), is equal to the nth coefficient at \((q_1,\ldots ,q_n)\) of the \((\#Q)\times (\#Q)\)-matrix

Proof

We start with the more intuitive case of finite color set \({\mathbb {X}} = \{1,\ldots ,\ell \}\) with \(\ell \in \mathbb {N}\). In this case, the Fredholm determinant is just the determinant of an \(\ell \times \ell \) matrix,

The analogue of (2.17) reads

Suppose we want to know the coefficient of some monomial \(z_{1}^{n_1}\cdots z_\ell ^{n_\ell }\) in the determinant. Then, clearly the only relevant contributions are from summands \((x_1,\ldots , x_r)\) with every entry \(x_i\) contained in the support \(\mathrm {supp}\, \varvec{n} = \{x:\, n_x \ge 1\}\), which plays the role of Q. The series is actually a sum, as all terms for \(r > \#Q\) are zero. Noticing that

we conclude

Turning back to general sets \({\mathbb {X}}\), the result follows as the coefficient only depends on \(\det (\mathrm {Id} - {\mathbb {K}}_z) \upharpoonright _{Q}\) as discussed before the lemma. \(\square \)

Determinants for z either with density or which are generalized functions. In several applications, it is not natural to restrict z to points. In statistical mechanics for example, it is typical that \(\mathbb {X} \subset \mathbb {R}^d\) and z has a density with respect to the Lebesgue measure. For such measures z the restriction to Q is always zero. In quantum field theory, one considers z which are only generalized functions and the restriction to points has no sense at all. However, one can re-interpret the Fredholm determinant in another way and give an expression in terms of usual determinants. Assume that z either has a density with respect to a reference measure m or that z is a generalized function. The density we denote as well by z and the duality between test and generalized functions we formally write as an integral. The nth. coefficient of (2.17) depends only on

where \(z( q_1) \ldots z( q_n)\) are interpreted as the n-fold tensor product of generalized functions. This shows that one can get the nth. coefficient by just computing the determinant of an \(n \times n\)-matrix

The determinant is well-defined, because in all expressions the generalized functions z are evaluated at different points. The Dirac deltas cause no problem, because they only lead to dropping integrals. Indeed, one just obtain (A.22), which is well-defined for generalized functions z.

Appendix B: Combinatorial Species with Uncountable Color Space

Formal power series in finitely or countably many variables have a natural interpretation as exponential generating functions for labeled, colored combinatorial species, which helps prove identities of power series identities independently of any convergence considerations. This point of view is formalized with Joyal’s theory of combinatorial species [7, 24]. Power series in several variables correspond to colored combinatorial species, also called multisort species [7], with one variable \(z_k\) per color or sort. See the survey by Faris [13] for an account in the context of cluster expansions and [11] for applications to Feynman diagrams.

This appendix extends the theory of combinatorial species generalizes the theory of colored species to infinite, possibly uncountable color space \(C\). Such generalizations were in fact already proposed by Farris [12] as well as Méndez and Nava [28]; however, their concepts of generating function there are too restrictive for our purpose. Indeed their generating functions are sums of monomials \(\prod _{k\in C} z_k^{n_k}\) indexed by multi-indices \(\varvec{n} = (n_k)_{k\in C}\) that have only finitely many nonzero entries \(n_k \ne 0\). Our generating functions instead are functions of measures \(z(\mathrm {d}x)\) on the color space \(C\). This is the kind of generating function that appears naturally in the statistical mechanics of inhomogeneous systems, where colors may correspond, for example, to positions \(x\in \mathbb {R}^d\) in space and the measure \(z(\mathrm {d}x)\) is a position-dependent activity [33].

Another difference with [28] is a more nuanced notion of family of power series. For finite color spaces and finitely many variables, it is natural to look at families \((F_k)_{k\in C}\) of generating functions, e.g., for rooted colored trees that have their root of color k. In our setup the relevant power series are either function or measure-valued. For example, rooted colored trees give rise to a family \((T_B^\bullet (z))_{B\subset C}\) indexed by sets \(B\subset C\) instead of elements \(k\in C\): to each set of colors \(B\subset C\) associate the generating function for trees whose root has color in B.

We proceed with a short self-contained description of our formalism, which is similar to [28] but has a different notion of generating function. We start with the concrete example of graphs. Let \(C\) be a non-empty possibly infinite set, the set of colors. Let V be a finite set, e.g., \(V = \{1,\ldots ,n\}= [n]\) with \(n\in \mathbb {N}\); V is the set of labels. A \(C\)-colored, labeled graph on V is a pair (G, c) consisting of (i) a graph G with vertex set V, (ii) a map \(c:V\rightarrow C\). Thus, every vertex of the graph is assigned both a label \(v\in V\) and a color \(c(v)\in C\). The pair (V, c) is a \(C\)-colored set. We write \(\mathcal {G}(V,c)\) for the collection of colored labeled graphs on V with prescribed coloring c.

Admissible relabelings of vertices are formalized with bijections: Let \((W,{\tilde{c}})\) be another finite colored set and \(\varphi :V\rightarrow W\) a color-preserving bijection, i.e., \({\tilde{c}}(\varphi (v)) = c(v)\) for all \(v\in V\). Relabeling the vertices v of a graph \(G\in \mathcal {G}(V,c)\) by \(w=\varphi (v)\) we obtain a graph \({\tilde{G}}\in \mathcal {G}(W,{\tilde{c}})\). In this way, \(\varphi \) induces a bijection between \(\mathcal {G}(V,c)\) and \(\mathcal {G}(W,{\tilde{c}})\). Choosing \(V=W=[n]\), we deduce that for every permutation \(\sigma \in \mathfrak {S}_n\), we have \(\#\mathcal {G}([n],c) =\#\mathcal {G}([n],c\circ \sigma )\). Put differently, \(\#\mathcal {G}([n],c)\) is a symmetric function of the variables \(c_i=c(i)\). The associated formal power series

is the (exponential) generating function of the species of labeled, \(C\)-colored graphs.

In the following, we consider the set of colors C to be fixed once and for all.

Definition B.1

A colored set is a pair (V, c) consisting of a finite set V and a map \(c:V\rightarrow C\). A color-preserving bijection \(\varphi :(V,c)\rightarrow (W,{\tilde{c}})\) is a bijection from V onto W such that \({\tilde{c}} = c\circ \varphi \).

The empty set \(V=\varnothing \) is considered a colored set. This is needed for the combinatorial counterpart of the variational derivative (see below) and allows for a conceptualization of pinned vertices that are not integrated over in generating functions. For example, we may be interested in the set of trees with vertex set \([n]\cup \{\star ,\circ \}\) where \(\star ,\circ \notin [n]\) are two distinct elements not in [n]. Then, \(n=0\) corresponds to trees with vertex set \(\{\star ,\circ \}\).

Sometimes we write colorings as vectors \((c_v)_{v\in V}\) and not as maps \(v\mapsto c(v)\).

Definition B.2

A labeled combinatorial species F with colors in C consists of two rules:

-

(1)

a rule \((V,c)\mapsto F(V,c)\) that assigns to every colored set a finite set (for \(V=\varnothing \) we write instead \(F(\varnothing )\)),

-

(2)

a rule that assigns to every color-preserving bijection \(\varphi : (V,c)\rightarrow (W,{\tilde{c}})\) between colored sets a bijection \(\Phi :F(V,c)\rightarrow F(W,{\tilde{c}})\) (relabeling),

that satisfy the following: for all color-preserving bijections \(\varphi _1:(V_1,c_1)\rightarrow (V_2,c_2)\), \(\varphi _2:(V_2,c_2)\rightarrow (V_3,c_3)\), the relabeling induced by \(\varphi _3=\varphi _2\circ \varphi _1\) is the composition of the relabelings, \(\Phi _3 =\Phi _2\circ \Phi _1\).

Put differently, a colored combinatorial species is a functor from the category of of colored sets (objects: finite colored sets, morphisms: color-preserving bijections) to the category of finite sets. In concrete examples, the concept of relabeling and its functorial property are often so natural that the rule \(\varphi \mapsto \Phi \) is left implicit.

Definition B.3

Let F be a labeled colored combinatorial species. Suppose that for each colored map (V, c), we are given a weight function \(w_{(V,c)}:F(V,c)\rightarrow \mathbb {C}\) and that for all color-preserving bijections \(\varphi :(V,c)\rightarrow (W,{\tilde{c}})\), \(w_{(W,{\tilde{c}})} \circ \Phi = w_{(V,{\tilde{c}})}\). The pair (F, w) of consisting of the species F and the family w of weights \(w_{(V,c)}\) is a weighted colored species.

By a slight abuse of notation we shall omit the indices and use the letter w both for the family of weight functions and for weight maps \(w:F(V,c)\rightarrow \mathbb {C}\).

Lemma B.4

Let (F, w) be a weighted colored species. Then for every \(n\ge 1\), every coloring \(c:[n]\rightarrow C\) and all \(\sigma \in \mathfrak {S}_n\),

Thus, \(\sum _{g\in G([n],c)} w(g)\) is a symmetric function of the color variables \(c(1),\ldots ,c(n)\) and we may apply the notion of formal power series. The elementary proof is left to the reader.

Definition B.5

The generating function of a weighted colored species (F, w) is the formal power series

Example B.6

(Colored singletons) Let \(B\subset C\) be a set of colors. The species of singletons with color in B is the species

The associated generating function is

compare Example 2.4.

Operations on formal power series correspond to operations on combinatorial species. We provide formulas for non-weighted species only, the generalization to weighted species is straightforward.

Cartesian product. Let F, G be two combinatorial species. We define a new species \(F\times G\) by

The generating function is \((F\times G)(z) = F(z) G(z)\), compare Eq. (A.2). Hence, an \(F\times G\)-structure on V is a pair (f, g) consisting of an F-structure on \(V_1\) and a G-structure on \(V_2\), with \(V_1,V_2\) a partition of V into possibly empty sets.

Derivatives. Let \((V,c)\mapsto G(V,c)\) be some colored combinatorial species. Suppose that for each finite set V there is a designated element \(\circ = \circ _V\) that is not in V, see Definition 5, Remark 6, and Exercise 16 in [7, Chapter 1.4]. Given \(q\in C\), we extend a coloring \(c:V\rightarrow C\) to a coloring \(c_q^\circ : V\cup \{\circ \} \rightarrow C\) by setting

Then we define a family \((F_q)_{q\in C}\) of colored species by

The generating function is

in which we recognize the variational derivative

see Eq. (A.4). We may think of objects in \(G_q^\circ \) as objects of G rooted in \(\circ \). For example, when \(G= T\) is the species of non-rooted trees, then \(T_q^\circ \) can be identified with the species of trees rooted in the non-labeled vertex (ghost) \(\circ \) with prescribed root color q.

Pointing. Let G be a species and (V, c) a finite colored set. For \(B\subset C\), define

For example, when \(G=T\) is the species of the non-rooted trees, \(T_B^\bullet \) corresponds to rooted trees with labeled root and root color in B. We have

Comparison with Eq. (A.7) yields

Compare Lemma 4.4 and the paragraph preceding the lemma.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jansen, S., Kuna, T. & Tsagkarogiannis, D. Lagrange Inversion and Combinatorial Species with Uncountable Color Palette. Ann. Henri Poincaré 22, 1499–1534 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00023-020-01013-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00023-020-01013-0