Abstract

This paper investigates the impact of human and political capitals of entrepreneurs on enterprise performance in four emerging nations.The rent generation potential of these capitals is a well established fact, however, much less is known concerning the contingent nature of their value creation prowess. In this work, we draw on institutional theory and dynamic managerial capabilities perspective to examine the interactive effect of country of origin economic developement level and the international experience of entrepreurs, on the capitals, with respect to a set of financial indicators. Employing a quantitative methodology, our findings reveal that the relationship between the capitals and enterprise performance are indeeed contingent with the capitals of home-grown entrepreneurs, rather than those of returnee migrant entrepreneurs, exhibiting a greater propensity to influence enterprise performance. We conclude with implications for theory and practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

This study examines the importance of a country’s economic development for returning migrants founded enterprises and the value that their political and human capital have in this process. We examine enterprise performance in four emerging nations within the context of the countries level of economic development (Fantom and Serajuddin 2016) and the entrepreneurs’ acquired capabilities they bring to their enterprises.

This study is unique in that it examines several emerging markets that vary on a number of characteristics including location, culture, political environments and stages of economic and institutional development. The study controls for host country location by comparing returning migrants with a sample on entrepreneurs who remained in the country and never lived overseas.

The value that capitals acquired while abroad by migrants is an area that has attracted some interest from the entrepreneurship and business research community. Some of this work has focused on the value that extended networks bring to a particular country’s enterprise growth (Light et al. 2017), while others have focused on the importance of migrants and the networks they develop in their host country, as well as, those they maintain in their home country both for flow of knowledge and formation of enterprises (Saxenian 2002, 2005). Most of these studies have looked at migrants and some of their capabilities such as their networks or human capital value while starting firms in their home countries, but none so far have attempted to understand if and how, the value of these capabilities will vary by location. By analysing migrant’s human and political capital within several emerging nations this paper attempts to better understand how the value of these capitals are is impacted by the location they are in and the value they may have on enterprise performance.

This research focuses on returning migrants and/ or transnational entrepreneurs who are typically individuals that have built and maintained multiple relations, familial, social, economic and political among others, that cross borders, while pursuing educational or economic opportunities abroad (Schiller et al. 1992). These individuals either by necessity, or perceived opportunities, return to their home country attracted by improving economic, social or political conditions (Saxenian 2002). At the same time these individuals establish enterprises in order to capitalise on some of these opportunities and acquired ideas, skills or networks.

The entrepreneur brings and transfers to the firm a series of capabilities that are specific to each individual. These capabilities then become key elements of the new firm’s competitive resources and allows it to both identify and respond to opportunities (Teece 2014). The two capabilities we look at in this study, human and political capital, have been found in past studies, when looked at individually, to be important to entrepreneur enterprise formation, development and performance (Davidsson and Honig 2003; Batjargal 2007; Becker 1964; Honig 1998). The study of the impact of two or more capitals on enterprise success has been more limited due to definition measurement of different capitals, the varying degrees of results from different studies, in some cases the different measuring tools used in each study and lastly, that the level of complexity grows significantly when looking at more than one capital at a time (Sanders and Nee 1996; Davidsson and Honig 2003).

In addition, some studies that specifically looked at migrants and enterprise formation have found that, too much human capital acts as a deterrent from both creation and development of enterprises and is probably due to risk/rewards factors, since entrepreneurship may compensate for lack of formal education as migrants seek higher income (Herman 1979; Basu and Altinay 2002) or for those who have it, higher paying jobs and less interest in starting a firm (Davidsson and Honig 2003); and, that self-employment and the start of an enterprise compensates for a lack of, or little understanding of, the educational background of the immigrant in their host country (Min 1984; Portes and Zhou 1996; Sanders and Nee 1996).

Political capital is the least studied of the two capitals. Some empirical and anecdotal evidence indicates that, at least in some countries, politically connected firms have preferential access to debt financing, contracts, and access to new markets, thus allowing for rapid internationalization of their firms (Faccio et al. 2006). Political capital studies have been more limited in their number and scope when looking at enterprise performance. This is partially due to the difficulty in finding ways to effectively measure it. However, some studies have been able to demonstrate that political capital does create value for an individual company (Faccio et al. 2006; Nee and Opper 2010). Most of the research in this area has focused on two general themes, corruption and the use of political connections for rent seeking purposes from local governments (Fisman 2001; Liu et al. 2013; Ufere et al. 2012).

The level of a country’s economic development and its impact upon entrepreneurship, and vice versa, is an area that is has not been usually included in economic studies despite the contributions by Schumpeter (1934) and other Austrian economic school economists (Van Stel et al. 2005). This has been partially attributed to measurement issues, however, it’s an area of research that has benefited from new ideas and sources such as the GEM surveys and new ways to view nations within an economic growth pathway rather than a static developed/ un-developed framework (Rosling et al. 2018; Fantom and Serajuddin 2016). The World Bank introduced a low, low-medium (LM), medium-high (MH) and high income country model in the late 80’s and has continued to update this classification by refining some of its components such as the purchasing power parities (PPP), based on exchange rates rather than local currencies, and applying the Atlas method developed by the World Bank (Fantom and Serajuddin 2016). However, the central idea that nations are constantly being reclassified as their economies develop and change, remains central to the concept. The term emerging nations still tends to refer to those below the high-income classification, however, we believe, the World Banks’ method of classification allows for better country groupings and analysis. The idea of economic and institutional development is a relatively new one.

This paper will explore within the framework of several emerging nations in three continents migrant’s human and political capital and the value this may have on enterprise performance. As part of this study we reviewed a significant part of the existing literature for the most widely used definitions for our study. All of our 132 respondents had the same base characteristics: they had been born and grown up in the country in which their enterprise had been started, regardless of the ethnic, religious or tribal affiliation and all were citizens of the country they were surveyed in. Due to this, we have defined our 2 sub-groups as follow: 1) A home-grown entrepreneur (HGE) represents an entrepreneur in any of the four countries who has never lived outside their home nation. 2) Migrant returnee entrepreneur (MRE) is used to describe the individual who has lived outside the home nation and returns and starts an enterprise. We believe within the context of our work these are the best definitions for our sampled population.

The importance of large diasporas has not been entirely ignored by countries with socio-economic issues, however it is those with fast growing economies that have realised their value and potential as transformative forces within their economies and have made concerted efforts to attract them back such as the cases of China and Taiwan and a lesser degree India (Saxenian 2002; Kenney et al. 2013). This has been reasonably well researched in the last 20 years, what has been far less explored is the cause and effects of returning migrants to other smaller, or less fast-growing economies. What is also still not well understood is how the combination of more than one capital, that migrants further accumulate or develop in their host country, may help or hinder in their enterprise’s performance. This research aims to further the understanding of, if and how, human and political capitals amongst migrants who started enterprises in their home countries benefit from the expatriation. It also aims to further the exploration and understanding on how migrants and their capitals perform in countries in different stages of economic development, and specifically in emerging economies, which has rarely been done so far. Although the sample is not meant to be representative of countries in any of the 4 stages of economic development, by using the World Bank classification, it is aimed to provide a fresh view of how migrant entrepreneurs enterprises perform in varying countries and economies.

This paper also aims to answer the call of this special issue by exploring the value of the flow of human and political capitals, both from and in emerging economies, by comparing those entrepreneurs that have left and returned, and those who never did, and the role this has in their enterprises performance. In addition we answer the call for papers that contribute to the debate related to institutional distance by exploring the potential impact migrant entrepreneurs have on their home country economies’ growth once they return. In addition, it informs policy makers within these emerging economies on how to facilitate their internal and international entrepreneurial ecosystems by attracting and retaining their diaspora within resource-constrained contexts.

The paper is structured as follows: First, it discusses the MREs’ capabilities in the form of human and political capital as well as the link of these capital with enterprise performance. Second, it presents the theory of dynamic managerial capabilities (DMC) framed within political capital and the link to enterprise performance. Third, it presents the set of hypotheses to be tested. This is followed by methodology, data analysis and then, it concludes.

Theory and hypothesis development

The entrepreneur brings and transfers to the firm a series of capabilities that are specific to each individual. These capabilities then become a key elements of the new firm’s competitive resources and allows it to both identify and respond to opportunities (Teece 2014). The theory that unites entrepreneurs and firm performance particularly under conditions of uncertainty and dynamism is dynamic capabilities.

The notion of dynamic capabilities emerged as a response to the static nature of resources and capabilities in combating changes in a firm’s environment. In contrast to the resource-based view (RBV), dynamic capabilities theory addresses how firms can sustain resource-based advantages in uncertain and dynamic environments (e.g. Eisenhardt and Martin 2000; Griffith and Harvey 2001). According to dynamic capabilities perspective, the firm needs to develop new capabilities to identify opportunities and to respond quickly to them (Teece 2014). Firms possessing dynamic capabilities are active generators of competitive resources from which managers “integrate, build, and reconfigure internal and external resources, skills and functional competencies to address rapidly changing environments” (Teece et al. 1997) (p. 516). Dynamic capabilities are leveraged by managers to help the firm implement new strategies in response to changing market conditions orchestrating available resources in new and different ways (Ambrosini and Bowman 2009; Teece et al. 1997; Zahra et al. 2006). Therefore, dynamic capabilities help explain the relationship between the quality of managerial decisions and firm performance (Sirmon and Hitt 2009).

Other theory that is increasingly used in entrepreneurship research is Institutional Theory. This theory helps to better understand the factors that contribute to the success of business ventures aside from entrepreneurial resources (Peng 2006). The economic and social pillars under which Institutional theory is founded, are important elements to explain how capitals are used between groups of countries. Therefore, in this paper, this theory helps in the selection and clustering of group of countries.

The study of the impact of two or more capitals on enterprise success has been more limited due to definition measurement of different capitals, the varying degrees of results from different studies, in some cases the different measuring tools used in each study and lastly, that the level of complexity grows significantly when examining more than one capital at a time (Sanders and Nee 1996; Davidsson and Honig 2003).

While the dynamic capabilities perspective has a strong western overtone, firms from emerging/transition economies are not sheltered from environmental exigencies. Economic liberalization and transition toward market systems (Yiu and Lau 2008) have been accompanied by rapid changes in economic, social and legal institutions in most emerging economies. As a consequence, firms from emerging economies find themselves growing in, yet hostile and rivalrous environments (Petzer et al. 2012). Therefore, having and/or developing dynamic capabilities is incumbent on emerging economies’ firms in order to sustain their competitiveness in the increasingly competitive domestic market. Performance of firms in emerging economies has also been shown to be related to an entrepreneur’s managerial competence (e.g., Madhok and Keyhani 2012; Evers 2011). Dynamic capabilities view is, however, a nascent and still underdeveloped research area in the entrepreneurship literature of emerging economies. As observed by Petzer et al. (2012), in emerging market firms, entrepreneurial decision making involves a unique role of resource, capital, configuration and transformation by continuously renewing firm competences so that strategic fit with the changing environment can be maintained.

Entrepreneurial capabilities - human and political capital

The DMC literature formally organizes the discussion on the strategic and entrepreneurial responsibilities of managers. It accentuates the importance of managers in their capacity as entrepreneurs (Teece et al. 1997; Tripsas and Gavetti 2000). This research agenda has led to the identification of managerial entrepreneurial actions that are allied with strategic changes and ultimately firm performance. The credit for this goes to Teece’s (2007) seminal work on the micro foundations of dynamic capabilities. According to Teece (2007), this is because those managers are able to (a) identify and capture new strategic opportunities, (b) orchestrate the necessary organisational assets, and (c) invent business models and new organisational forms (Augier and Teece 2008). These strategic functions are nevertheless not a given, managers need to be adequately resourced, such being the case, Adner and Helfat (2003) define DMCs as “the capabilities with which managers build, integrate, and reconfigure organizational resources and competencies” (Adner and Helfat 2003) (p. 1012). The idea of DMCs thus links the managerial entrepreneurship functions with antecedent managerial properties.

Adner and Helfat (2003) propose managerial human capital, managerial social capital and managerial cognition as the underpinning attributes of DMC. Managerial human capital includes the skills and knowledge repertoire of managers, which are shaped by their education and personal and professional experiences (Becker 1993; Castanias and Helfat 2001). Through path dependent and historical experiential learning managers acquire and develop specialised knowledge and skills. Managers’ formal and informal network ties help acquire essential embedded resources and provide them with critical information for decision making (Geletkanycz and Hambrick 1997).

All three elements of DMC are intertwined and linked to the notion of managerial dominant logic. Managers’ dominant logic refers to the way in which managers conceptualize the business and make critical resource allocation decisions (Prahalad and Bettis 1986). This logic represents management’s view of the world, where the firm stands in its business environment, and what it ought to be doing (Tomsic 2013). While a growing body of evidence supports the influence of formative elements of DMC on firm performance under dynamic conditions, it is our contention that the conceptualisation of DMC is potentially incomplete. This is particularly true in the context of the institutional environment faced by emerging market firms. Contrary to developed economies where distribution of resources is allied closely to the market, the state institutions still hold considerable sway over who can access what in emerging economies. Given the prevalent circumstances, the literature on entrepreneurship in emerging economies has recognised political ties and connections as primary sources of resource capital that firms must acquire in order to remain competitive. According to Peng et al. (2005), three kinds of capital are critical for firms in emerging markets: social capital, reputational capital, and political capital. Empirical work attesting to the influence of DMCs on firm performance tend to examine them individually. For example, the impact of managerial cognition on venture growth is examined by Baum and Bird (2010). Acquaah (2007) investigates the role of managerial social capital on a firm’s financial performance while Haber and Reichel (2007) establish a connection between human capital and several accounting metrics such as revenue and profit. A similar approach is adopted in this study in that attention is focussed on human and political capital and their contingent relationship with enterprise performance in the context of emerging economies.

Defining political capital has proven elusive with Casey (2008) describing reference to the term as fleeting and ill fitting. It is common to allude to political capital as a form of social capital, for example, Bourdieu (2002) (p. 16), refers to political capital as a variation of social capital and “the source for observable differences in patterns of consumption and lifestyles”. Noticeably, this definition is rather vague, nevertheless the similarity between social and political capital has been recognised elsewhere in the sense that these forms of capital accrue in relational ties. However, unlike social capital, Nee and Opper (2010) argue that political capital has the additional feature of being connected to political power and thus it is rooted in institutional structure. In this work, political capital is viewed as the “benefits from cultivating continuous relationships with governments such as social legitimacy and political effectiveness” (Yiu and Lau 2008) (p. 41).

Political connections are extremely important in emerging economies (Yiu and Lau 2008) as governments play a key role in shaping the environments under which organisations must operate (Pearce et al. 2009). Due to a lack of market-supporting structures, governments in some emerging economies are actively involved in setting industry standards, guiding business policies, and influencing corporate operations (Sheng et al. 2011). Additionally, in most emerging economies the government is still the main gatekeeper to funds, information and support services to firms (Yiu and Lau 2008). Together, these circumstances help to create a market for political products, or simply put, a political market (Sun et al. 2012) setting the stage for exchange between entrepreneurs and political actors. The valuable resources embedded in the political market can potentially be exploited and leveraged by well-connected entrepreneurs. Thus, building relationships with various government agencies is imperative for a firm survival (Ghauri et al. 2012).

By treating the government as another factor of production, supplier of inputs, or as an agent that needs to be managed in its pursuit of competitive success (Boddewyn and Brewer 1994), entrepreneurs can act politically to outperform their competitors by reducing their own production and transaction costs (e.g. through subsidies) and thus provide cheaper, better, or unique products to their customers (Ge et al. 2017). Political capital can therefore be thought of in terms of a capability in view of the fact that politically-connected entrepreneurs enjoy advantages in gaining access to important resources and opportunities that are critical to business profitability and survival (Park and Sehrt 2001; Zhou 2000). For example, politically connected entrepreneurs in China received preferential access to credit (Zhou 2000), tax breaks and government bailouts during tough economic times (Li et al. 2008). Further, as Baron and Markman (2003) observe, political capital can be coordinated with entrepreneurs’ other capabilities in shaping their strategic market activities and performance. Limited empirical work investigating the influence of political capital of entrepreneurs on firm performance in emerging economies has framed political capital as a dynamic managerial capability. One exception is Yiu and Lau’s (2008) work in which the authors adopt a dynamic capability approach to examine the relationship between corporate entrepreneurship and resource capital configuration and transformation in emerging market firms. In this work, political capital is shown to be an important dynamic managerial capability that entrepreneurs can draw on to affect firm performance in emerging economies.

MREs, dynamic managerial capabilities and enterprise performance

Although this paper deals primarily with the impact of MRE’s capital(s) and entrepreneurs in multiple locations, it draws from Jones and Coviello’s (2005) general model, which considers the following four constructs: 1) the external environment, the countries and their economical and institutional level 2) the internal environment, or resources, 3) the entrepreneur and 4) the enterprise’s performance. We have drawn from this basic model to examine the relationship of the firm’s performance and the interaction of the capitals found within the MRE. Massey and España proposed that migration forges new networks in the host nation that in turn feeds the migrations that produced them (Massey and España 1987). Migrants have also had a strong influence in co-developing enterprise hubs and economic development both in their home and host locations. Transnationals have been shown to use their acquired human capital, both education and experience, as well as, their dual network base to start enterprises and entrepreneurial hubs (Saxenian 2005).

As outlined in the research model, see Fig. 1. Returning migrants and transnationals build fields in both their adopted and home nations which are by nature both multiple and complex. These multiple relationships may be a mix of familiar, economic, social, religious, financial and political that span multiple borders (Schiller et al. 1992). Chinese and Indian students and Silicon Valley engineers, who decide to repatriate, face wide variations in national, economic and political institutions. MREs thus develop variety of adaptations to the particular challenges in their home countries (Saxenian 2005). Transnationals become adept at finetuning their acquired capitals in order to maximize on their dense personal, political networks and intimate local knowledge and tend to play a central role in coordinating economic linkages between the two (Saxenian 2005). Returning migrants may also face the issue of capital erosion and its impact on enterprise creation and performance, an issue that has not received much attention by researchers so far, although here is some empirical evidence that social capital erosion does happen within communities in transition or change (Jacob and Tyrell 2010; Štulhofer 2004; Zhang et al. 2015), however, there is little work so far examining either the effects of the erosion of political capital and/or the coping mechanisms of immigrants when faced with this erosion.

The importance of returning and transnational migrants to a country’s economy has been the focus of both government and academic interest. Taiwan, realising the value of its diaspora, in 1980, opened the first of several science industrial parks with special economic incentives. By 2000, 118 of the 289 enterprises in these parks, employing over 100,000 people, had been founded by returning émigrés and transnationals, mainly from the US, who maintained close technological and business links with the country they studied and/ or worked in (O’Neil 2003). China followed suit, with over 2000 start-up enterprises created by returning migrants in just one Chinese industrial park, Zhongguancun Science Park (ZSP), alone (Dai and Liu 2009), thus showing the country’s success is attracting back its far-flung nationals. Other nations, such as Romania and India’s efforts on this front have been more modest (Deloitte, Touche 2014).

This paper considers jointly issues in migration studies, and international entrepreneurship: First, how the home country’s level of economic and institutional development may affect returning migrants’ capitals value with regard to their enterprises performance; and second, it moves away from a single capital analytical lens to trying to find meaningful ways to understand the interaction of different capitals. These issues are closely related both theoretically and empirically. Some of these issues have benefited from a significant amount of academic research while others less so, and although the two issues may be closely related, they have rarely been considered together. Because of this, the relationship between migrants, the capitals, their locational value and their impact upon entrepreneurship and enterprise performance remains an area that is only been partially explored and is less complete than it could be.

The heterogeneity amongst entrepreneurs extends beyond their relative capabilities. Although DMCs provide a means of examining intrapreneurs’ differences, it leaves out an important element, the context. Institutional theory can help to close this gap because it is concerned with how groups and organizations are able to secure their position and legitimacy by adhering to the rules and norms of the institutional environment they face (Meyer and Rowan 1977; Scott 2007) (as cited in Bruton et al. 2010) (p. 422). This environment is categorised by Scott (2007) into three pillars: the regulatory pillar, a rational actor model of behaviour, derived from studies in economics and based on laws, sanctions and enforcements; the normative pillar, representing a model of organisational and individual behaviour, which studies how institutions guide certain behaviours by defining what is expected socially and commercially; and the cognitive pillar, an individual behaviour model dealing with internal rules and meanings which limit the individuals’ beliefs and actions. As noticed, the regulatory and normative pillars evaluate contextual factors at the macro level whereas the cognitive pillar focuses on the micro level. This study is concerned with the individual or the micro level analysis, the cognitive pillar in Scott’s classification. Specifically, the use of capital accumulation of MREs. Nevertheless, to control for some regulatory and other macro level factors, several indexes where used in the selection of countries (more details in the methodology section) and then, these countries where grouped using the World Bank’s 4 level classification based on income.

“Context” is particularly important as it has been shown that context often mediates the impact of capitals on performance. For instance, Nee and Opper (2010) advance the notion of institutional domains as a variable of institutional elements that shape the environment in which organisational actors transact. According to the authors, institutional domains are distinct institutional arrangements that enable and guide economic transactions, and these can contribute to either preserve or reduce the value of political capital. Additionally, context can manifest to equip entrepreneurs with varying degrees of capitals. For example, the literature often distinguishes between return migrant and HGE. It is believed that due to their experience and exposure to contextual discontinuities abroad, MREs accumulate human capital, over and above their counterparts in their home country. It can thus be argued that the value of capitals may not be automatic but varies directly with contextual conditions. In the next section hypotheses are developed to illuminate these contingent relationships.

Hypotheses development

It has been argued that the understanding of institutions by economists was limited and it was not until the mid-nineties that the local specifies of institutional changes that come with economic development were started to be recognized in the literature (Nayyar 2007). The impact of this has been renewed interest in exploring the Schumperian view that the entrepreneurial process is one of the aspects of economic growth, which in turn leads to the role institutions and government policy (Toma et al. 2014; Wennekers et al. 2005; Acs and Szerb 2007). This renewed interest in entrepreneurship has in turn led nations to take a more active role in attracting migrants to return to their countries of origin (Kilic et al. 2009; Wahba and Zenou 2012). It has also been argued extensively by economists and social scientists that the economic development level (EDL) of a country is not only closely linked to the development and robustness of its institutions, but also the creation and development on industries, and their related enterprises. As Ehrlich (1981) pointed out that single indicators, such as GNP or GDP, can be less and less determined to be true to reality, yet practically every international comparison tries to express levels of economic development compressed into a single indicator such as the Human Development Index (HDI), life expectancy, income per caps, agricultural land, net savings, government deficits, gross capital formation and so on. These indicators in turn are compressed into a comprehensive synthetic indicator, which scholars use, for lack of a better one, to suit to particular studies and approaches to quantify the level of development (Ehrlich 1981). Some scholars have and continue to find a positive relationship between GDP per caps and the opportunity ratio that in turn correlates with more enterprises being formed and has formed the backbone of the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor report (GEM) (Acs 2006). For this study we have considered multiple indices that lead to country classifications and groupings. This has included simple classifications such as GDP, somewhat more complex indices such as the World bank’s income grouping and highly complex ones such as HDI. We decided after analysing each of them and running different analytical models to use the World Bank’s income classification, which has been discussed in greater detail in the methodology section. We thus propose the following hypothesis:

-

H1.

The EDL of an entrepreneur’s home country is positively related to firm performance.

Migration and repatriation issues are getting more attention in the literature. This research explores the capabilities of MREs within the home nation’s economic and institutional context and explores the value that their human and political capital may bring to the enterprise. The combination of these capitals is not only unique to each MRE and are part of the base resource the entrepreneur utilises to exploit opportunities in the market, but its value is also directly influenced by the local economic and institutional environment. We therefore assume that each individual migrant influences the firms’ performance. The individual migrant’s international experience has a direct relationship to accumulation of additional education or experience, a process we have labelled the ‘top-up’ and/or the erosion or loss of networks in the home country, particularly political capital. This is usually either working or studying. It is likely that that experience is of importance to the firms’ operations and performance.

The link between human capital and enterprise performance is well established (Davidsson and Honig 2003; Rauch et al. 2005). This linkage has been built over the past century as researchers first defined the term and then started to investigate its impact on enterprise creation and performance. The debate on the value of human capital has gone from one extreme that argues that human capital could generate long term growth, which became one of the critical features of the ‘new growth’ literature initiated by Lucas (1988), to the other extreme that argues that human capital, as an ordinary input, is unable to generate any endogenous growth (Mankiw et al. 1992). Although in the past the vast majority of human capital and enterprise performance work has found positive correlations between the two (Gimeno et al. 1997; Robinson and Sexton 1994; Ganotakis and Love 2012), one inherent weakness is that human capital theory assumes more is better. The variance within individuals may point towards over investment and underutilization. Thus, the weakness lies in that ‘it essentially takes a black box view of educational production and accumulation activities at equilibrium’ (Davidsson and Honig 2003) (p. 305). Over accumulation may result in less appetite for risk taking, diverting the potential entrepreneurs away from enterprise formation or development into higher paying institutional employment, thus higher levels of education may actually have a negative impact on enterprise performance (Honig 1998). On the other hand, low levels of education may stimulate entrepreneurship and risk taking among populations whose ability to secure jobs are restricted.

Some migration related entrepreneur’s studies that have looked at human capital have focused on knowledge acquired overseas to explain enterprise performance (Dai and Liu 2009; Bai et al. 2017). Some studies demonstrate that returnee enterprises benefit from the returnee’s international experience and international market knowledge (Bai et al. 2017; Li et al. 2008) and that their enterprise performance is better than that of local entrepreneurs’ enterprises due to their technical and commercial knowledge (Dai and Liu 2009).

Political capital is the least studied of the two capitals. Some empirical and anecdotal evidence indicates that, at least in some countries, politically connected firms have preferential access to debt financing, contracts, and access to new markets, thus allowing for rapid internationalization of their firms (Faccio et al. 2006). Political capital studies have been more limited in their number and scope when analysing enterprise performance. This is partially due to the difficulty in finding ways to effectively measure it. However, some studies have been able to demonstrate that political capital does create value for an individual company (Faccio et al. 2006; Nee and Opper 2010). Most of the research in this area has focused on two general themes, corruption and the use of political connections for rent seeking purposes from local governments (Fan et al. 2007; Fisman 2001; Liu et al. 2013; Ufere et al. 2012). In this study we consider both the amount of and the effects that loss of political capital or erosion (Siegel 2007), particularly among migrants, may have on enterprise performance. This has been of particular interest since what little work that has been done with respect to erosion of capitals, has mainly focused on the erosion of social capital (Kesler and Bloemraad 2010).

Migrant and/or transnational founded enterprises may also benefit from the learning advantage of newness (Zahra et al. 2006). When firms are new and have a less rigid organizational structure it enables the transfer of internationally gained knowledge which can thus be easily shared with new employees and aid the firm’s operations and performance vis-a-vis those founded by HGM enterprises. Among the returning migrant population it is quite probable that while migrants accumulate human capital overseas, they may lose or at least stop accumulating and developing their political capital. These returning migrants may believe that there is a need to invest resources into re-acquiring a perceive loss of political capital, erosion, in order to compete effectively with home-grown founded enterprises, particularly in less developed nations and potentially neglecting the enhancement of other capabilities. What migrants may not consider in this approach is the evolution of economies as the progress from low to high income nations and the corresponding strengthening of the country’s institutions which may make political capital less relevant for their enterprise’s performance. The following two hypothesis are proposed:

-

H2.

Entrepreneurs’ political capital has a net positive impact on performance.

-

H3.

Entrepreneurs human capital has a net positive impact on firm performance.

The value of human capital and enterprise performance has been extensively explored (Davidsson and Honig 2003). While in the past there has been much debate as to reaching a single vision on both definition and measurement, most current work has returned to Mincer’s (1958) approach of measuring the quantity of education and/or experience. The quality and the effects of the location of the value of human capital are less understood. Some studies that specifically analysed migrants and enterprise formation have found that, too much human capital acts as a deterrent from both creation and development of enterprises and is probably due to risk/rewards factors, since entrepreneurship may compensate for lack of formal education as migrants seek higher income (Herman 1979; Basu and Altinay 2002) or for those who have it, higher paying jobs and less interest in starting a firm (Davidsson and Honig 2003); and, that self-employment and the start of an enterprise compensates for a lack of, or little understanding of the educational background of the immigrant in their host country (Min 1984; Portes and Zhou 1996; Sanders and Nee 1996). The returning MRE may try to capitalize on the additional human capital acquired in the host nation and transfer it to the firm in their home nation. This is specially the case at the time the migrant starts and develops the firm and the number of people hired is small. Possess a low stock of knowledge or low-level networks (Bai et al. 2017). This may be of particular importance in developing economies where education and certain types of experience not only are expensive and hard to acquire but may also be linked to an individual’s socio/ economic levels in the country and the networks associated (Heckman and Yi 2012). Considering the above we hypothesize:

-

H1.

A positive relationship between political capital and firm performance holds only when the entrepreneur is homegrown and from a LM income country.

-

H2.

A positive relationship between human capital and firm performance holds only when the entrepreneur is homegrown and from a LM income country.

Methodology

Country selection

To achieve the stated objectives of this research the following methodology was used. We examine all four economies and the two groupings as case studies. A survey instrument was designed, the completion of the initial draft of the survey, follow-up pilot interviews conducted, and the results analysed. This in turn resulted in the refinement of the survey instrument and some of the political capital questions, and a larger-scale sampling to achieve statistically robust results, and a better final analysis.

The research was carried out in three steps. In step one, a pilot was run with 12 respondents, the survey was then modified and updated. The selection of the four country(s) used in this research was made using a dedicated algorithm that included country rankings from the following data bases: the Gross Domestic Product (GDP), GDP per capita, using the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM)‘s Global Entrepreneurial and Development Index (GEDI), The Global Ease of Doing Business Index (GEDBI), The Global Corruption Index (GCI), and international migration data (World Bank, OECD). The final country selection was done by eliminating the worst fit countries in order to focus on high migration indices and refining the selection criteria by continent to those countries with the highest emigration, and by default returning/ transnational migrants. The final countries selected were Colombia, Poland, Nigeria and Romania in order to keep the final list of participating countries as geographically diverse as possible. A snowball approach was used utilising the research team’s own networks.

Sample

The Data that are used is 132 competed questionnaires from entrepreneurs in four countries. The average number of respondents per country was 33. The target respondents between returning/transnational migrants and HGEs was 50% each, in every country. This was roughly achieved in Romania and Poland while Colombia and Nigeria had larger numbers of HGMs (see Table 1). Initially 487 entrepreneurs were contacted of which 163 completed the questionnaire, a 33.4% response rate. A further 31 were dropped due to incomplete information, not meeting the minimum requirements, the enterprise being in operation for less than 12 months, not having a minimum of five employees, thus eliminating the one-man band consultancy effect, or not being able to do the follow-up interview. This resulted in a 27.1% completion rate. The final data set reflects the elimination of inaccurate, partial or unverifiable information. The final sample size appears to be well within the average for these types of studies, especially for those involving human capital and entrepreneurs or enterprise performance (Unger et al. 2011).

In this research, the term entrepreneur is used to refer to individuals that set up a business or businesses, taking on financial risks in the hope of profit. MREs are defined as individuals who return to their home countries to start up a new venture after living abroad (Drori et al. 2009, cited in Bai et al. 2017), while a transitional is a returning migrant that may have residences in both the host and home nations at the same time (Schiller et al. 1992; Portes et al. 2002). This study included both MREs and HGEs in equal parts where possible but no less than 35% of the total sample in a country. None of the entrepreneurs in the data set had started a non-for-profit, charity or social enterprise. All the enterprises were more than a year old. The individuals that completed the survey and participated in the follow-up interview had been part of the original start-up and remained both as a significant shareholder, above 10%, and actively involved in the enterprise’s operations.

We define a returning migrant, as an individual who has lived outside their home nation for more than 12 months and returns to his or her home nation, while a transitional is a returning migrant that may have residences in both the host and home nations at the same time. We include both returning migrants and transnationals as one group and explore their enterprise performance both within a country’s economic and institutional development framework and against those that have never left their home country (Saxenian 2005). Entrepreneur’s capabilities in this study uses Mincer’s (1958) definition of human capital as both education and work experience. Political capital definition is based on Bourdieu’s’ transformative nature of capitals, which may be defined as the combination of other types of capital for the purpose of the return of an investment in this capital within the system of production (Casey 2008), in which political capital takes its form from the arena within which it is utilized.

Data collection and research process

The survey was designed utilizing Grootaert et al.’s 2004 Social Questionnaire model (SC-IQ) and cross-cultural survey guidelines (Survey Research Center 2016). Questions were created to help gather the required data and address education, training, experience, and where they were acquired, as well as, memberships and affiliations and the perceived value and use of these affiliations. A follow-up interview allowed for the data collected on the survey to be verified. The first phase of this research was designed to establish the relationships between variables and concepts and at the same time, to establish the links, between each respondent and the entrepreneurial firm. None of the participants were minors nor belonged to a vulnerable group. Respondents were given the opportunity to review their final survey answers and transcripts, and withdraw if the so desired, before they were incorporated into the data set. None choose to do so. The ethical approval was granted by the University of Leeds.

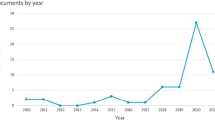

The data was analysed primarily using the revenue dependant variable, however, results using the profit dependant variable were also run and the results included in order to highlight a particular outcome. It should also be noted that this survey does not constitute a statistically representative sample of returning migrants and/or of entrepreneurs in any of the four countries, since the total population of returnees or of entrepreneurs is unknown for any of the countries. The data collected from each enterprise was crosschecked with available public information. For a more detailed explanation of the variables, see Table 5. The financial data was analysed using Hierarchical Ordinary Least Squares modelling (OLS). In addition, since all companies reported their data in a local currency, comparison in real terms unit terms across the complete sample was normalized in two ways. The first was using a single unit of measure, in this case USD and then the log of this measure, and the second was to normalize the revenues in their local currency by country and using the log of this measure. The dependent variable was revenue for a 3-year period (2013–2015).

Variables

The choice of dependent variables was limited to profits and revenue by data and reporting constraints but was guided by economic and business theory (Richard et al. 2009). Since most respondents were small start-up enterprises the data collection to 3 years. Economic theory both suggests that enterprises and individuals are driven by maximizing both revenues and profits. It also suggests that individuals attempt to collect and maximize the use of capitals, in this case human and political capital. Business theory and in particular, dynamic capabilities theory suggests that the heterogeneity of the firm is based on the value of the capitals brought by each entrepreneur.

Human capital is analysed measuring the individuals’ education, number of degrees, and experience, number of working years prior to starting the enterprise. Political capital is the aggregation of ten null variables that include political affiliations, use of bribes, and perceived value derived from affiliations and networks. The study controlled for entrepreneur age, firm age, years since founding, and the total number of employees (firm size). For a more detailed description of the variables see Table 5.

Control variables

We controlled for Human Development Index (HDI), time spent abroad and the age of the entrepreneur. The HDI has been used as a country control in studies examining the determinants of firm performance in emerging and developing nations (e.g., Mersland and Strøm 2009). HDI is a UNDP indicator that assesses the development of countries based on certain capabilities of people in these countries (Iqbal et al. 2019). It encapsulates three social measures; standard of living; knowledge; and life expectancy (Nguyen et al. 2020). A higher value indicates higher productivity of the labour force of the country which is expected to increase the financial performance of firms (Streeten 1994). The duration of stay of a migrant abroad can have a detrimental effect on their political capital. People who migrate do not often stay in touch with well-placed contacts and acquaintances in their home country while they are away (Piracha 2015). These connections are one of the key means of acquiring privileged information and possibly political favours. The more time spent abroad by a migrant widens the communication gap which can be difficult to bridge upon return particularly where the political landscape is dynamic. Studies investigating the demographics of entrepreneurs on firm performance in emerging nations have found a positive linkage between the two. For example, in a study of 250 entrepreneurial Pakistani firms, Khalid et al. (2011) found a strong and positive association between firm performance and the age of entrepreneur. This means that as entrepreneurs grow older, they tend to have a greater impact on their firm performance.

The correlation matrix showing the intercorrelations between the study variables and some demographic indicators are shown in Table 2. Notable relationships include the significant and negative correlations between the EDL measured as a dichotomous variable, and human capital (r = −.349, p < 0.01), revenue (r = −.321, p < 0.01) and HDI (r = −.566, p < 0.01), all suggesting that entrepreneurs from MH income countries fared better on these indices. Human capital and political capital share a significant, medium sized correlation (r = .187, p < .05). The variable migrant is a dichotomous measure representing migrant and homegrown samples. The correlations between migrant and political capital as well as between revenue growth are all insignificant indicating that in and of itself and ceteris paribus, being a migrant or a homegrown entrepreneur does not impact on political capital or enterprise performance. However, the intercorrelation between migrant and human capital (r = −.124, p < .05) suggests that homegrown entrepreneurs tend to have greater human capital than MREs. Also of interest is the significant intercorrelation between HDI and revenue growth (r = .388, p < .01).

The total sample (see Table 1) allowed us to group these into MRE (57) and HGM (74). We then sub-divided the four countries into two groups based on Rosling’s four level country classification (Schell et al. 2007; Rosling 2013; Rosling et al. 2018) and World Bank (Fantom and Serajuddin 2016) reclassification of country GNI: high, upper-middle, lower-middle, and low. The selection of the two groups was based on all 4 countries being in groups 2 and 3 (upper-middle and lower-middle) at the time of the survey, Poland has subsequently been reclassified as a high-income country by the World Bank in 2018, and the inclusion of these countries into the GEM report for the entire period of the study, neither Nigeria nor Romania we included in the GEM survey for the years in question and thus were grouped together. The final two groups were: Colombia-Poland (group 1) both upper middle-income countries and Nigeria-Romania (group 2) a lower-middle and upper-middle income country. In view of the three years of revenue data, in the final step of data preparation we transformed the revenue data into panel data for the analysis rather than averaging. This resulted in a final data sample of 396 for the analysis.

One of the objectives mentioned earlier of this study was to attempt to better understand the value of human and political capital within the one entity that is the migrant entrepreneur in emerging nations. Previous studies that have analysed more than one capital have also separated each one in their analysis (Davidsson and Honig 2003). The focus here is on the agent, the entrepreneur, and his or her education, experience and networks. In simple terms: one looks inward to the individual and what has been personally accumulated: years of experience or degrees, for example; while the other on the external relationships that by their very nature involve other individuals and that strength of relationship does not allow for easy measurement formulas. However, it can be argued that one cannot exist without the other, Schuller (2001).

Data analysis and empirical results

We employed OLS hierarchical regression analysis to test the hypotheses. The variables were entered using a three steps process. In the first step the control variables (HDI, time spent abroad and age) were entered. This was followed by the main predictor variables (political capital, human capital, migrant and EDL). In the last step we included the interaction variables (PC*migrant and HC*migrant). These variables were constructed to examine the moderating effect of political and human capital respectively on the migrant variable. To achieve this, it was necessary to mean-centre the continuous variables following which the new variables were created as a product with the migrant variable. Two samples were created by splitting the original sample employing the EDL variable, this enabled model comparison between the LM and the MH countries to be effected. Performance was measured as revenue growth, making use of data which was available for three years (2013, 2014 and 2015) to achieve this, the data was transformed into a panel format creating a sample of 396 from the original 132.

The fixed effects of the OLS hierarchical regression are displayed in Table 3. In the first step both HDI (β = .382, p < .001) and age (β = .167, p < .001) displayed significant relationships with revenue whereas time spent abroad (β = −.008, ns) did not. This suggests that higher levels of HDI has a fixed effect on firms’ revenue growth, in addition to this, it appears that entrepreneurs tend to have a greater impact on firm performance as they grow older. In the second step HDI and age remained significant predictors along with the new variables EDL (β = −.127, p < .05), political capital (β = .156, p < .01) and human capital (β = −.143, p < .01). These results indicate that after controlling for HDI, time spent abroad and age, the variables EDL, political capital and human capital are all significant predictors of growth in revenue. In the case of the dichotomous variable EDL, 1 represents MH income countries while 2 represent LM income counties. The minus sign thus suggests that the relationship between EDL and revenue holds only for the MH income countries sample and hence in support of H1. These results also lend support to H2 that suggests an overall positive relationship between PC and performance and H3 that assumes a net negative relationship between HC and performance.

The results for the final step of the hierarchical regression show that previous significant relationships held with the exemption of HC (β = −.084, ns). Both interaction terms, PC*migrant (β = −.141, p < .01) and HC*migrant (β = .105, p < .05) returned significant results. The migrant variable is dichotomous with 0 representing homegrown entrepreneurs and 1 for MREs. The presence of the minus sign thus indicates that the relationships tested held for homegrown rather than MREs. Therefore, the results indicate that the relationships between both PC and HC in relation to revenue hold only for homegrown entrepreneurs. In the final step to test H4 and H5, the sample was split between MH and LM income countries. As can be observed in Table 3 the interaction terms, PC*migrant (β = −.182, p < .05) and HC*migrant (β = −.184, p < .10), returned significant results for the LM sample and nonsignificant results for the MH sample, PC*migrant (β = −.114, ns) and HC*migrant (β = .012, ns). These results are further illustrated in Figs. 2 and 3, together, they serve to support the hypotheses advanced by H4 and H5 respectively.

Discussion

In this study we set out to examine the dynamics of entrepreneurship and firm performance in the context of emerging countries. We drew on dynamic managerial capabilities and the institutional theory to conceptually frame our study which gave rise to five unique hypotheses, four of which were accepted. In the first instance, we hypothesised an economic development level (EDL) effect on firm performance (H1). The results show that there was a significant difference between the medium-to-high (MH) income country sample and the low-to-medium (LM) income country sample in explaining the variance in revenue growth. The results show that the MH income country sample appeared to be a significant predictor of revenue growth compared to the LM income country sample after controlling for HDI. This difference might be due to entrepreneurs from MH economies benefitting from better local economic conditions and improved institutional environment. Economist have attributed this effect due to the shift from a model of the ‘managed economy’ toward that of an ‘entrepreneurial economy’ in more developed economies (Van Stel et al. 2005). Our results appear to confirm a more general study that analysed the amount of entrepreneurial activity in 37 countries that participated in the GEM, and found that entrepreneurial activity does not seem to change in a continuous way as the economies develop but is different in different stages of development (Van Stel et al. 2005). Further, previous studies have also examined country effect on firm performance (e.g., Makino et al. 2004; Bamiatzi et al. 2016) and found a positive relationship between larger economies and firm performance, however, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the broader economic development level effect as prescribed by the World Bank in the context of emerging economies.

Few studies have examined the relationship between entrepreneurs’ political capital and firm performance in the emerging economies context, exemptions include Fan et al. (2007) and Liu et al. (2013). In line with previous studies we found that an entrepreneur’s political capital does indeed influence revenue growth (H2). However, previous studies do not examine the contingent nature of political capital, thus, through H4 we demonstrated that the fixed effect of political capital on revenue holds only when the entrepreneur is homegrown and domiciled in a LM income home country. Post hoc analysis of political capital for the migrant and EDL samples show that there was a significant difference (F (1, 394) = 2.86; p = 0.10) of political capital across the migrant sample with HGE (m = 5.45) exhibiting higher levels than MRE (m = 5.07). However, the difference in political capital between MH countries (m = 5.17) and LM countries (m = 5.39) was insignificant (F (1, 394) = 0.93; p = 0.335). These findings suggest that in LM income nations enterprises founded by HGE with high political capital have a competitive advantage against the rest of the enterprise population. One of the major stumbling blocks to institutional development, and by default economic development, is corruption in its many forms. A study covering roughly one third of the words countries points out that corruption slows economic development particularly in countries with weak governance and political institutions (Aidt 2009) and allowing for political connections to have higher value in enterprise formation and development. Thus, returning migrants may have suffered from erosion of their political capital find themselves at a disadvantage in countries with weaker institutions.

Contrary to the hypothesised relationship we found that human capital had a net negative impact on firm performance (H3). This is in spite the positive relationships observed for homegrown migrants from LH income countries (H5). Post hoc analysis of human capital for the migrant and EDL samples show that there was a significant difference (F (1, 394) = 6.60; p = 0.10) in human capital levels across the migrant sample with HGE (m = 5.70) exhibiting higher levels than MRE (m = 4.88). There was also a significant difference (F (1, 394) = 54.55; p = 0.01) in human capital across the EDL sample with MH countries (m = 6.50) exhibited much higher levels of human capital than LM countries (m = 4.20). While it is surprising that HGE exhibited higher levels of human capital than RME, it is not a surprise that MH countries showed higher levels than LM countries. The findings tend to suggest that intra-entrepreneurial capitals matter less to firm performance in MH country compared to LH country. Given the weaker institutions in LH income countries, entrepreneurs seek to compensate by building intraindividual capitals in order to survive and thus are able to leverage them in a more creative ways to benefit their enterprises. Furthermore, it may be the case that the less educated and experienced migrants that start enterprises in LH countries face a weak institutional environment making it more of a struggle to achieve success compounded with diminished political capital needed to survive in such an institutional environment.

Conclusion

This is a first study that has sought to examine the contingent nature of entrepreneurial success in an emerging nations context with a particular focus on returnee migrant entrepreneurs, dynamic managerial capabilities, and the economic development level of home nations. The findings of our study help to illuminate those contingent relationships, we discuss the resulting policy and theoretical implications below.

Contributions to policy and theory

Firstly, our study contributes to knowledge about the contingent nature of entrepreneurial success in emerging nations. It reveals that a one-size fits all approach to emerging economies in researching country effect on firm performance may not provide a complete picture of the dynamics that are at play. In this line, our study contributes to the conversation on country effects with respect to firm performance suggesting that there might be nested models of economic development within broader categorisations that may be exercising influence on firm performance. As such, our study also carries some policy implications. Economic development level is not the only distinguishing features among emerging nations, however, there is a correlation between EDL and good institutions and governance that are favourable to entrepreneurship and firm growth. As a first step in improving their institutional environment LH income countries could look for inspirations from fellow MH income countries that fall under the emerging countries umbrella.

Entrepreneurship in its various forms is linked to job creation (Malchow-Møller et al. 2011) and therefore an important economic development tool for emerging nations. Thus secondly, our study is an eye opener in exposing the hard truths about becoming a successful migrant returnee entrepreneur in emerging economies. The literature is sympathetic to the view that overall MREs make substantial contributions to their home economies due to their entrepreneurial orientations. It is also believed that MREs are equipped with higher levels of dynamic managerial capabilities such as human capital. While this may well be true, our study shows that there is a disconnect between the accumulation of capitals and entrepreneurial success. Consequently, our work contributes to opening this black box by exposing the contingent nature of entrepreneurial success. From a policy perspective, our study implies that there is work to be done to help create a level playing field enabling MREs to play a more active role in the socio-economic landscape of their home countries. As suggested above, strengthening of institutions in LH countries could be a good starting point as this would lead to a move away from the reliance on political capital which carries a negative connotation in some circles.

Previous literature has discussed the importance of social capital, viewed as a more acceptable form of networking, to the success of MREs (Canello 2013), how this could be developed to usurp the role of political capital should be actively explored by governments from LH income countries. Furthermore, the impact that the level of economic and institutional development play in returnee migrants’ use of human and political capital is of importance for policy makers with large diasporas and efforts to attract and re-integrate them. This reasoning shines a light back on the arguments presented above regarding the levelling of playing field to allow a more active participation of returning migrants in the economy.

Finally, from a theoretical perspective, our findings address the contingent nature of political capital as a dynamic managerial capability in the context of emerging economies. Studies conducted in developed nations have tended to adopt a broad-brush approach to DMCs portraying them as universally beneficial. Our findings suggest that DMCs might well be contingent on external conditions such as the economic development level of a country. In a similar fashion to political capital, our findings show that in the emerging economies context, external contingencies may well play vital a role in determining the efficacy of human capital in relation to entrepreneurial endeavours firm success. Therefore, it may be argued that in the context of emerging economies, the theory of dynamic managerial capabilities may well need a rethinking to incorporate intervening influences that are likely to be key determinants in respect to performance outcomes.

Limitations and future research

There are also some limitations that we need to acknowledge in this study. The sample was drawn from a small number of countries. We believe the selection of method was both robust and random, the four countries selected may or may not be fully representative of small and medium enterprises in emerging markets. The design of the overall study is cross-sectional, and hence it is subject to the inherent limitations of cross-sectional studies. The research design and the ad hoc analysis point to a limited likelihood of common method bias in the data. It should also be noted that the snowballing method may have resulted in proximity bias.

The results in this study also point to the need for future research that further explores how different capitals interact within individuals and how these interactions take both different forms that result in differences in performance in different combinations of low to high income countries. In addition, future research may find better insights and benefit from grouping nations and the importance of variances in migrant’s capabilities when forming and developing enterprises in their home country.

Finally, in this study, we employed revenue growth as the proxy for firm performance. Future research could, for example, utilise such alternative measures of firm performance as sales, profitability, growth, and Tobin’s Q (Bamiatzi et al. 2016).

References

Acquaah, M. (2007). Managerial social capital, strategic orientation, and organizational performance in an emerging economy. Strategic Management Journal, 28(12), 1235–1255.

Acs, Z. (2006). How is entrepreneurship good for economic growth? Innovations: Technology, Governance. Globalization, 1(1), 97–107.

Acs, Z. J., & Szerb, L. (2007). Entrepreneurship, economic growth and public policy. Small Business Economics, 28(2–3), 109–122.

Adner, R., & Helfat, C. E. (2003). Corporate effects and dynamic managerial capabilities. Strategic Management Journal, 24(10), 1011–1025.

Aidt, T. S. (2009). Corruption, institutions, and economic development. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 25(2), 271–291.

Ambrosini, V., & Bowman, C. (2009). What are dynamic capabilities and are they a useful construct in strategic management? International Journal of Management Reviews, 11(1), 29–49.

Augier, M., & Teece, D. J. (2008). Strategy as evolution with design: The foundations of dynamic capabilities and the role of managers in the economic system. Organization Studies, 29(8–9), 1187–1208.

Bai, W., Johanson, M., & Martín, O. M. (2017). Knowledge and internationalization of returnee entrepreneurial firms. International Business Review, 26(4), 652–665.

Bamiatzi, V., Bozos, K., Cavusgil, S. T., & Hult, G. T. M. (2016). Revisiting the firm, industry, and country effects on profitability under recessionary and expansion periods: A multilevel analysis. Strategic Management Journal, 37(7), 1448–1471.

Baron, R. A., & Markman, G. D. (2003). Beyond social capital: The role of entrepreneurs' social competence in their financial success. Journal of Business Venturing, 18(1), 41–60.

Barro, R. J., & Lee, J. W. (2013). A new data set of educational attainment in the world, 1950–2010. Journal of Development Economics, 101, 184–198.

Basu, A., & Altinay, E. (2002). The interaction between culture and entrepreneurship in London’s immigrant businesses. International Small Business Journal, 20(4), 371–393.

Batjargal, B. (2007). Internet entrepreneurship: Social capital, human capital, and performance of internet ventures in China. Research Policy, 36(5), 605–618.

Baum, J. R., & Bird, B. J. (2010). The successful intelligence of high-growth entrepreneurs: Links to new venture growth. Organization Science, 21(2), 397–412.

Becker, G, S. (1964). Human Capital. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Becker, G, S. (1993). Human Capital. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Boddewyn, J. J., & Brewer, T. L. (1994). International-business political behavior: New theoretical directions. Academy of Management Review, 19(1), 119–143.

Bourdieu, P. (2002). Outline of a theory of practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bruton, G. D., Ahlstrom, D., & Li, H. L. (2010). Institutional theory and entrepreneurship: Where are we now and where do we need to move in the future? Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 34(3), 421–440.

Canello, J. (2013). Migrant entrepreneurs and local networks in industrial districts: Outsiders in the clubhouse? Fortaleza, Brazil: Global conference (2014) of the Regional Studies Association.

Casey, K. (2008). Defining political capital: A reconsideration of Bourdieu’s interconvertibility theory. St Louis, USA: Lab for integrated learning and technology: University of Missouri.

Castanias, R. P., & Helfat, C. E. (2001). The managerial rents model: Theory and empirical analysis. Journal of Management, 27(6), 661–678.

Dai, O., & Liu, X. (2009). Returnee entrepreneurs and firm performance in Chinese high-technology industries. International Business Review, 18(4), 373–386.

Davidsson, P., & Honig, B. (2003). The role of social and human capital among nascent entrepreneurs. Journal of Business Venturing, 18(3), 301–331.

Deloitte, Touche (2014). Tohmatsu India Private Limited. Mumbai: Ready referencer for overseas Indians.

Drori, I., Honig, B., & Wright, M. (2009). Transnational entrepreneurship: An emergent field of study. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 33(5), 1001–1022.

Ehrlich, E. (1981). Comparison of development levels: Inequalities in the physical structures of National Economies. In P. Bairoch & M. Lévy-Leboyer (Eds.), Disparities in economic development since the industrial revolution. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Eisenhardt, K. M., & Martin, J. A. (2000). Dynamic capabilities: What are they? Strategic Management Journal, 21(10–11), 1105–1121.

Evers, N. (2011). International new ventures in “low tech” sectors: a dynamic capabilities perspective. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development. https://doi.org/10.1108/1462001111155682.

Faccio, M., Masulis, R., & McConnell, J. (2006). Political connections and corporate bailouts. Journal of Finance, 61(6), 2597–2635.

Fan, J. P. H., Wong, T. J., & Zhang, T. Y. (2007). Politically-connected CEOs, corporate governance and post-IPO performance of China’s partially privatized firms. Journal of Financial Economics, 84(2), 330–357.

Fantom, N. & Serajuddin, U. (2016). The World Bank’s classification of countries by income. The World Bank.

Fisman, R. (2001). Estimating the value of political connections. American Economic Review, 91(4), 1095–1102.

Ganotakis, P., & Love, J. (2012). Export propensity, export intensity and firm performance: The role of the entrepreneurial founding team. Journal of International Business Studies, 22, 1–26.

Ge, J., Stanley, L. J., Eddleston, K., & Kellermanns, F. W. (2017). Institutional deterioration and entrepreneurial investment: The role of political connections. Journal of Business Venturing, 32(4), 405–419.

Geletkanycz, M. A., & Hambrick, D. C. (1997). The external ties of top executives: Implications for strategic choice and performance. Administrative Science Quarterly, 42, 654–681.

Ghauri, P., Hadjikhani, A. & Elg, U. (2012). The three pillars: Business, state and society: MNCs in emerging markets. In Business, society and politics. Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Gimeno, J., Folta, T., Cooper, A., & Woo, C. (1997). Survival of the fittest? Entrepreneurial human capital and the persistence of underperforming firms. Administration Science Quarterly, 42, 750–783.

Griffith, D. A., & Harvey, M. G. (2001). A resource perspective of global dynamic capabilities. Journal of International Business Studies, 32(3), 597–606.

Grootaert, C., Narayan, D., Jones, V. N., & Woolcock, M. (2004). Measuring social capital: An integrated questionnaire. The World Bank. https://doi.org/10.1596/0-8213-5661-5.

Haber, S., & Reichel, A. (2007). The cumulative nature of the entrepreneurial process: The contribution of human capital, planning and environment resources to small venture performance. Journal of Business Venturing, 22(1), 119–145.

Heckman, J, J. & Yi, J. (2012). Human capital, economic growth, and inequality in China (no. w18100). Cambridge: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Herman, H, V. (1979). Dishwashers and proprietors. In Ethnicity at work (pp. 70–90). London: Palgrave.

Honig, B. (1998). What determines success? Examining the human, financial, and social capital of Jamaican microentrepreneurs. Journal of Business Venturing, 13(5), 371–394.

Iqbal, S., Nawaz, A., & Ehsan, S. (2019). Financial performance and corporate governance in microfinance: Evidence from Asia. Journal of Asian Economics, 60, 1–13.

Lutz, W., & Samir, K. C. (2011). Global human capital: Integrating education and population. Science, 333(6042):587–592.

Jacob, M. & Tyrell, M. (2010). The legacy of surveillance: An explanation for social capital erosion and the persistent economic disparity between east and West Germany. Available at https://ssrn.com/abstract=1554604.

Jones, M, V. & Coviello, N, E. (2005). Internationalisation: conceptualising an entrepreneurial process of behaviour in time. Journal of internationalbusiness studies, 36(3), 284–303.

Kenney, M., Breznitz, D., & Murphree, M. (2013). Coming back home after the sun rises: Returnee entrepreneurs and growth of high-tech industries. Research Policy, 42(2), 391–407.

Kesler, C., & Bloemraad, I. (2010). Does immigration erode social capital? The conditional effects of immigration-generated diversity on trust, membership, and participation across 19 countries, 1981–2000. Canadian Journal of Political Science/Revue canadienne de science politique, 43(2), 319–347.

Khalid, G, K., Farooq, S, U. & Raza, S, H., (2011). Empirical study of employment growth rate in small and medium enterprises. Global Journal of Management And Business Research, 11(1).

Kilic, T., Carletto, C., Davis, B., & Zezza, A. (2009). Investing back home return migration and business ownership in Albania. The Economics of Transition, 17(3), 587–623.

Li, H., Meng, L., Wang, Q., & Zhou, L. A. (2008). Political connections, financing and firm performance: Evidence from Chinese private firms. Journal of Development Economics, 87(2), 283–299.

Light, I., Bhachu, P. & Karageorgis, S. (2017). Migration networks and immigrant entrepreneurship. In Immigration and Entrepreneurship (pp. 25–50). Oxford: Routledge.

Liu, Q., Tang, J., & Tian, G. (2013). Does political capital create value in the IPO market? Evidence from China. Journal of Corporate Finance, 23, 395–413.

Lucas, R. (1988). On the mechanics of economic development. Journal of Monetary Economics, 22(1), 3–42.

Madhok, A., & Keyhani, M. (2012). Acquisitions as entrepreneurship: Asymmetries, opportunities, and the internationalization of multinationals from emerging economies. Global Strategy Journal, 2(1), 26–40.

Makino, S., Isobe, T., & Chan, C. M. (2004). Does country matter? Strategic Management Journal, 25(10), 1027–1043.

Malchow-Møller, N., Schjerning, B., & Sørensen, A. (2011). Entrepreneurship, job creation and wage growth. Small Business Economics, 36(1), 15–32.

Mankiw, G., Romer, D., & Weil, D. (1992). A contribution to the empirics of economic growth. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 107(2), 402–437.

Massey, D. S., & España, F. G. (1987). The social process of international migration. Science, 237(4816), 733–738.

Meyer, H. D., & Rowan, B. (2006). Institutional analysis and the study of education. The new institutionalism in education, 1–13.

Meyer, J. W., & Rowan, B. (1977). Institutionalized organizations: Formal structure as myth and ceremony. American Journal of Sociology, 83(2), 340–363.

Mersland, R., & Strøm, R. Ø. (2009). Performance and governance in microfinance institutions. Journal of Banking & Finance, 33(4), 662–669.

Min, P. G. (1984). From white-collar occupations to small business: Korean Immigrants’ occupational adjustment. The Sociological Quarterly, 25(3), 333–352.

Mincer, J. (1958). Investment in Human Capital and Personal Income Distribution. Journal of Political Economy, 1(4), 281–302.