1. Introduction

Currently the traditional three-gender system (masculine, feminine, and neuter) is being replaced by a two-gender system (common and neuter) in many Norwegian dialects (see, among others, Lødrup Reference Lødrup2011, Rodina & Westergaard 2015a, and Busterud et al. 2019). Previous studies have not always attributed much significance to the sociolinguistic function of grammatical gender. For example, Lundquist & Vangsnes (Reference Lundquist and Vangsnes2018) analyze gender processing in speakers’ native and non-native dialects. The differences they find between groups can be explained in terms of differences in the amount of input: The speakers of the minority dialect receive extensive input from the majority dialect, whereas the speakers of the majority dialect receive limited input from the minority dialect. Hence, they “have no need to invoke factors of language sociology into [their] analysis” (Lundquist & Vangsnes Reference Lundquist and Vangsnes2018:2).

The amount of input is put forward as a crucial explanatory factor for both the mono- and bilingual acquisition of gender (for example, Rodina & Westergaard 2015b). However, even if the variation and current changes within the grammatical gender system can be explained with reference to frequency in input and/or the difficulty in distinguishing the masculine and the feminine due to syncretism (see section 2.1), some data are still unaccounted for. For instance, an increased use of certain types of feminine gender marking is found among speakers of dialects where a change from a three-gender to a two-gender system has supposedly taken place (Opsahl Reference Opsahl, Knut, Rødningen and Tangen2017, Fløgstad & Eiesland Reference Fløgstad and Eiesland2019). This paper claims that sociolinguistic insights—regarding both macro- and micro- perspectives—are of relevance for the study of variation and change within the grammatical gender domain.

The question pursued in the following is to what extent exponents of grammatical gender are tied indexically to identity categories (for example, Bucholtz & Hall 2005, Eckert Reference Eckert2008). The claim is that grammatical gender marking may be associated with various indexical values such as urban/rural distinctions, political views, class, and ethnicity. This approach implies that speakers sometimes make a conscious decision to use certain gender markers. Indeed, Enger (Reference Enger, Bonami, Boyé, Dal, Giraudo and Namer2018:249) points out that “even inflection class suffixes can be manipulated consciously, and not only by linguists.” Thus, the interplay between speaker agency—that is, the conscious use of gender features in identity work—and the apparent reduction of the gender systems is central to my analysis. This interplay also presents the rationale behind the title of the paper, “Dead, but Won’t Lie Down?”.

In this study, I adopt a social constructivist perspective inspired by what Eckert has referred to as “third wave sociolinguistics.” The social meaning of variables is the focus of interest within this framework, and especially the contribution of variables to styles. Style is “a clustering of linguistic resources and an association of that clustering with social meaning” (Eckert Reference Eckert, Eckert and John2001:123). It is assumed that identity is not based on fixed social categories; rather, it is a relational and sociocultural phenomenon. Hence, the manifestation of identity in discourse is of particular interest, rather than the correlation between linguistic features and social variables per se (Bucholtz & Hall 2005, Quist Reference Quist2008). This manifestation is known as stylistic practice, which is “the process through which signs and differences become meaningful resources in daily enterprises and activities” (Quist Reference Quist2008:50). Stylistic practice is central to indexical processes, which create semiotic links between linguistic forms and social meaning (Eckert Reference Eckert2008). As pointed out by Bucholtz & Hall (2005:593), indexicality is thus fundamental to the way in which linguistic forms are used to construct identity positions:

In identity formation, indexicality relies heavily on ideological structures, for associations between language and identity are rooted in cultural beliefs and values—that is, ideologies—about the sorts of speakers who (can or should) produce particular sorts of language.

Indexical processes occur at all levels of linguistic structure and language use; hence, both micro-level linguistic structures and entire linguistic systems—such as dialects—may be tied indexically to identity categories (Bucholtz & Hall 2005:597). This means that while analyzing the social meaning of a linguistic feature, one must take into account the specific sociohistorical context in which the meaning of this feature originated (Johnstone Reference Johnstone2016). One must also remain open to the possibility of micro-level interactional negotiation altering the indexical value of a linguistic feature. The altered indexical value of a linguistic feature becomes less idiosyncratic through habitual practices, or what Agha (Reference Agha2003:81) has referred to as enregisterment, “whereby performable signs become recognized (and regrouped) as belonging to distinct, differentially valorized semiotic registers by a population.”

The structure of this article is as follows. In section 2, I start by presenting an overview of the Norwegian gender system (section 2.1) before turning to a presentation of the meaning potential associated with gender in different domains, from written varieties (section 2.2) and language contact scenarios (section 2.3) to semantics (section 2.4) and pragmatics (section 2.5). Section 3 is devoted to a general discussion and concluding remarks.

2. Indexical Values Across Time and Space

2.1. The Norwegian Gender System

Presenting an overview of the Norwegian gender system is not an easy task. We are faced with extensive variation. Norway does not have a spoken standard language in the traditional sense; instead, it has rich dialect variation and two official written standards, Bokmål and Nynorsk. Bokmål, ‘book language’, is used by the majority of Norwegians and can be traced back to Danish-influenced urban varieties.Footnote 1 Nynorsk, ‘new Norwegian’, is based on Ivar Aasen’s compilations of rural dialects in the 19th century. In most traditional Norwegian dialects—and in the Nynorsk written standard—three gender categories can be identified: masculine, feminine, and neuter. Gender assignment is more or less nontransparent in Norwegian; hence, gender can only be identified when nouns appear with associated words, such as the indefinite article, as in the following Nynorsk standard examples: ein stol(m) ‘a chair’, ei hylle(f) ‘a shelf’, and eit bord(n) ‘a table’ (Faarlund et al. Reference Faarlund, Lie and Vannebo1997). Three genders are also available in Bokmål, where the corresponding indefinite articles are en, ei, et. The Bokmål standard also allows feminine nouns to take masculine agreement, resulting in a system with two genders: common and neuter. The latter system also characterizes the city dialect of Bergen (for example, Jahr Reference Jahr and Jahr1998).

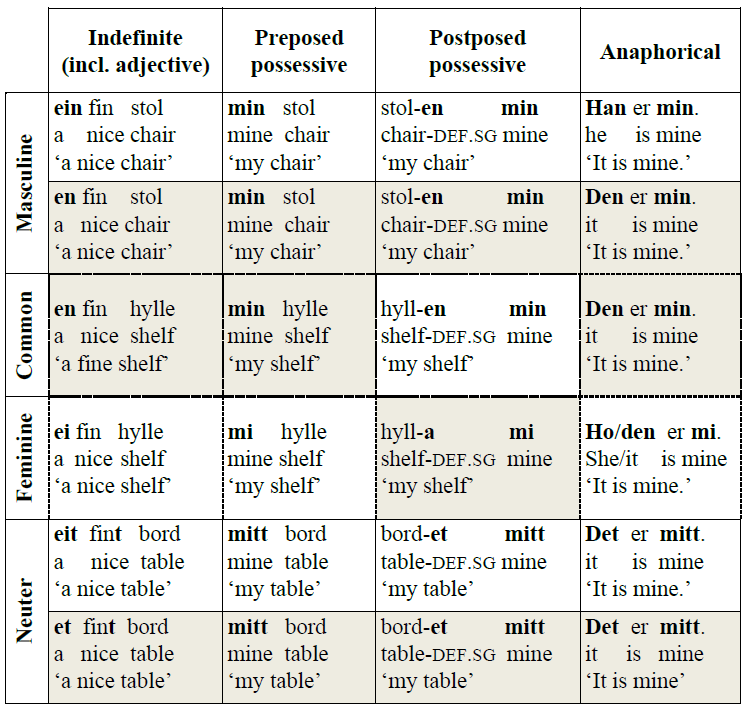

Table 1 combines the most prominent examples of how gender is realized in Norwegian. The Nynorsk standard—with a system corresponding more or less to most of the traditional dialects—is presented above the corresponding Bokmål variants within the masculine and neuter gender category in the table. Taking the masculine as an example, the Nynorsk standard on top reads ein fin stol (m) ‘a nice chair’, min stol (m) ‘my chair’, etc., whereas the Bokmål standard reads en fin stol (m) ‘a nice chair’, min stol (m) ‘my chair’, etc. As mentioned above, the Bokmål standard allows in addition for either a feminine category (in parallel with Nynorsk) or a common/neuter system. The shaded cells illustrate the most widespread features of the Bokmål written standard and the contemporary Oslo dialect (see section 2.2).

Table 1. Lexical gender in Norwegian.

There is syncretism between the masculine and the feminine in the adjectives, as in en fin stol(m) and ei fin hylle(f). In addition, Norwegian displays double definiteness, marking definiteness both with a suffix on the noun itself, on the adjective, and on a prenominal determiner, as in den (def) fine (def) stolen (def) , det (def) fine (def) bordet (def). There is syncretism between the masculine and the feminine here as well, with den being used for the masculine and feminine and det being the neuter.

The complexity of the linguistic situation in Norway is especially conspicuous in the common and feminine rows in the middle part of table 1. These are not clear-cut categories when it comes to the features included, which is illustrated with dotted lines. While the feminine indefinite article ei(f) is virtually absent in the (modern) spoken varieties associated with the capital Oslo, as well as in widespread variants of the Bokmål written standard, the feminine definite suffix -a still appears on feminine nouns, as in hylla (def) mi ‘my shelf’ (Opsahl & Nistov 2010, Lødrup Reference Lødrup2011, Enger Reference Enger, Bonami, Boyé, Dal, Giraudo and Namer2018). The gender system is reduced, but at the same time a more complex declension system has evolved, since the new common gender has two declension classes in the definite form, en stol–stolen ‘a chair–the chair’ and en hylle–hylla ‘a shelf–the shelf’ (Rodina & Westergaard 2015a; Lohndal & Westergaard 2016).

The definite suffix, -en(m), -a(f), and -et(n), is strongly linked with gender.Footnote 2 In some varieties gender can be considered the main factor in the allocation of nouns to inflection classes (Sollid et al. 2014:189). A lengthy discussion among Norwegian scholars has taken place as to the status of the definite suffix, and evidence has been put forward in support of seeing the definite suffix as a declension class marker rather than an exponent of gender (see, among others, Fretheim 1985, Enger Reference Enger2004, Lødrup Reference Lødrup2011, Lohndal & Westergaard 2016, Enger Reference Enger, Bonami, Boyé, Dal, Giraudo and Namer2018). There is little doubt that the definite article—being a suffix—behaves differently from the free gender morphemes in contexts of acquisition and change (Enger Reference Enger, Bonami, Boyé, Dal, Giraudo and Namer2018:235). The difference between bound and free morphemes has been shown to be significant in the acquisition rate (Rodina & Westergaard 2015b). Mono- and multilingual children acquire noun inflection systems earlier and more easily than the abstract rules of gender agreement (Rodina & Westergaard 2013; see also Cornips & Gregersen 2017:123). Also, in Heritage American Norwegian, there are differences between bound and free morphemes. Knowledge of the definite form of a feminine or neuter noun does not facilitate the production of conventional indefinite forms (free morphemes), which leads Lohndal & Westergaard (2016) to the conclusion that suffixes do not express gender. According to Enger (Reference Enger, Bonami, Boyé, Dal, Giraudo and Namer2018:237), “the definite singular suffix -a might seem ‘the last redoubt’ of the old feminine.” The -a suffix may still convey specific indexical values associated with the feminine gender marking.

2.2. Social Meaning of Gender in the Written Standards

As mentioned above, there is room for variation within the Bokmål written standard, but the shaded cells in table 1 illustrate the most widespread features, considered by some a neutral norm, where all possessives and adjectives are masculine, with the exception of certain instances of postnominal possessives, which are feminine, as in hylla(fsg.def) mi (f) ‘my shelf’. Considering certain parts of the system as neutral is not without certain risks. There is no room in this paper to present a justified account of Norwegian language planning (for an overview in English, see Vikør Reference Vikør2015, among others), but simply put, language planning during the 20th century was aimed at converging the two written standards, Bokmål and Nynorsk. This policy was officially abandoned in 2002. Merging Bokmål and Nynorsk would mean challenging dominant ideologies and blurring the sociolinguistic boundaries that were based on the indexical values associated with each variety, and in particular with their morphological composition (Jahr Reference Jahr2014). These ideologies promote a particular sociogeographic pattern and a particular set of indexical values: The Nynorsk standard is prototypically associated with the western parts of Norway and expresses the indexical values traditional, rural, peripheral, local, and sometimes old-fashioned (Mæhlum Reference Mæhlum2007:197). The fact that Nynorsk is a mandatory subject in school is often met with negative attitudes among pupils, especially in urban areas dominated by Bokmål. In contrast, the Bokmål written standard and (southeastern) spoken varieties close to it are the prototypical bearers of indexical values such as modern, urban, and superregional; Bokmål and its associated varieties are often considered sociogeographically neutral (Mæhlum Reference Mæhlum2007:194).

This picture reveals a sociolinguistic hierarchy, with the Bokmål written standard and related spoken varieties—especially the ones used by the middle class in Oslo—being the most prestigious ones. Bokmål, and especially the variety with a two-gender system, resembles the Danish system on which it is based; the managerial class and the urban elite had strong connections to Denmark, both during and after Danish rule. Thus, a seemingly innocuous grammatical feature, such as feminine agreement, as in hylla (def.sg) mi(f) ‘my shelf’, may trigger resentment as it is historically associated with less prestigious varieties.

Social indexical meanings and sociolinguistic hierarchies are not stable; they must be viewed in their local and/or sociohistorical context and in light of the dominant language ideology. An example of an alternative pattern of prestige is found in Solheim’s studies of the western Norwegian industrial town of Høyanger (Solheim Reference Solheim2008), where eastern Norwegian forms were introduced to the local community due to industrialization. However, some of these forms were too strongly associated with both Bokmål standard and the former managerial class to be acceptable in a western Norwegian context. As a result, they were rejected by the following generation of speakers (Kerswill Reference Kerswill and Hickey2013:240–242).

Still, there is reason to consider the two-gender variant of Bokmål as a prestigious variety within the current dominant language situation. In addition to the official variant of Bokmål that allows a three-gender system, an unofficial variety called Riksmål exists, with strong links to historically prestigious varieties. Riksmål stays true to its Dano-Norwegian heritage and maintains a two-gender system. The Riksmål variety—which in its modern version is more or less identical with a conservative Bokmål standard—is preferred in formal writing by many people; it is regulated by the Norwegian Academy for Language and Literature and is available through the large online dictionary Det Norske Akademis ordbok (NAOB; the Dictionary of the Norwegian Academy).Footnote 3 This dictionary is the largest and most complete record of conservative, or moderate Bokmål to date, but the feminine indefinite article ei is not displayed as part of the lexical entries for feminine nouns (NAOB 2018).

Lødrup (Reference Lødrup2011) bases his study of the loss of the feminine gender in the Oslo west dialect on the Oslo part of the Norwegian Speech Corpus NoTa, built in 2004–2006. NoTa-Oslo contains videotaped interviews and conversations with 166 informants across three generations from different parts of Oslo. Lødrup (Reference Lødrup2011:132) points out that the level of formality associated with an interview situation might have affected the occurrence of feminine gender marking negatively. If Lødrup’s suggestion is correct, then a two-gender system without the feminine gender is the preferred choice in formal contexts for these speakers, as already suggested for formal writing above.

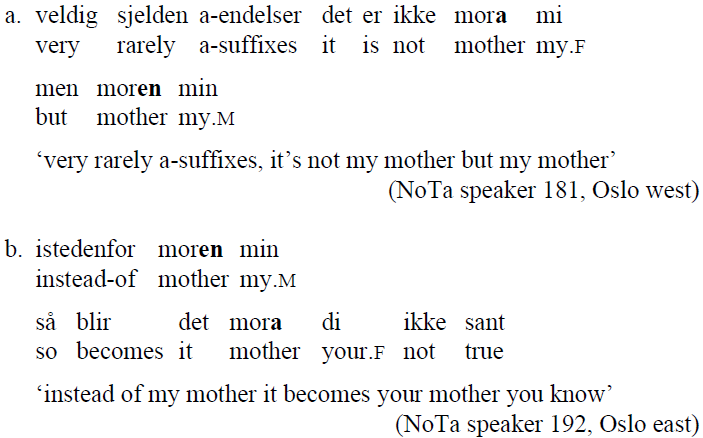

Throughout the language planning history of the 20th century, ever since the written reform of 1917, markers of the feminine gender have occasionally been called “vulgar” and even “ugly” (Jahr Reference Jahr2014, Ims Reference Ims2019). The first efforts to slowly merge the two written varieties in 1917 were met with strong opposition, especially with respect to the feminine definite a-suffix, as well as the a-suffixes in certain verb classes, and certain plural noun forms. These a-suffixes are indexical of the traditional working class areas in eastern Oslo; as such, its use has a clear social meaning, which is relevant for establishing the so-called radical or popular variant of the Bokmål written standard (see, for example, Ims Reference Ims2019). Evidence that feminine gender marking is an exponent of a certain style is found in metalinguistic reflections in the NoTa-Oslo corpus, where the speakers identify and illustrate sociogeographical differences by pointing to the presence or absence of feminine gender marking.

(1)

Another speaker points out that the use of the a-suffixes is associated with being “radical and freaked out” (NoTa speaker 041). This resembles the reaction the researcher Irmelin Kjelaas received from a group of journal editors a few years ago, which ignited a debate on the stylistic norms of scientific texts written in Norwegian Bokmål. The editors pointed to Kjelaas’ use of the indefinite feminine article ei and the a-suffixes as something not to be expected in scientific texts (Kjelaas Reference Kjelaas2017). In the debates about the radical form of the Bokmål written standard (see, for example, Lillealtern Reference Lillealtern2010), radical may also refer to one’s political views, and stylistic practices involving certain Bokmål features are sometimes labeled “AKP-m-l-Norwegian” (see, among others, Müller Reference Müller2017). AKP was the Workers’ Communist Party associated with the Marxist-Leninist movement of the 1970s. The left-wing politicians associated with this movement, such as Tron Øgrim, cultivated a sociolect with an emphasis on, among other things, the use of feminine forms (Brekke Reference Brekke2015). The party had most of its origin in the eastern parts of Oslo, which again highlights the sociogeographical dimension of Norwegian language hierarchies.

2.3. Gender, Geography, Ethnicity, and Contact

Corpus data retrieved from the UPUS project (Utviklingsprosesser i urbane språkmiljø [Linguistic Developments in Urban Spaces]; see, among others, Svendsen & Røyneland 2008, Hårstad & Opsahl 2013) show how young speakers in multicultural neighborhoods in Oslo use grammatical gender as one of several linguistic (and nonlinguistic) resources in their negotiation of identities or personae typically associated with a multiethnolectal speech style. This behavior is not restricted to the Norwegian context. These findings resemble the results of earlier research showing that grammatical gender is used in a slightly different way among speakers in multiethnolectal youth groups as opposed to speakers of more traditional monoethnic varieties (see, for instance, Kotsinas 1988, Quist Reference Quist2008, Wiese Reference Wiese2009). Cornips (Reference Cornips2008) shows how groups of friends in multiethnic neighborhoods in Utrecht construct social identities by using the common definite determiner de in cases where the neuter determiner het is required, according to standard Dutch (see also Cornips & Hulk 2006).

A comparison of young speakers’ linguistic practices across different speech situations revealed that some linguistic features were restricted to certain situations and interactional functions (Svendsen & Røyneland 2008, Opsahl & Nistov 2010:52). The most striking feature was the violation of the verb second constraint, resulting in an XSV word order (where X is a topicalized element, V the finite verb, and S the subject). V2 violations are often found in Norwegian L2 learner data, but in the UPUS corpus, this was clearly not the case (Opsahl & Nistov 2010:54). Other stylistic features at play were phonological (compare Svendsen & Røyneland 2008:72), as well as lexical and discourse features (for example, loan words from migrant languages represented in the neighborhood, including discourse markers such as wallah ‘swear by Allah’). The adolescents also used nonlinguistic resources to express their identity: They identified with hip-hop music, which was also visible in their choice of clothing and accessories, and many of them were proud of their sociogeographical belonging, with ties both to the local multiethnic neighborhood and to a globalized world. Among the few metalinguistic utterances in the UPUS interviews, some concerned grammatical gender.

Table 2 shows the distribution of gender-marked noun phrases produced in conversations by 22 of the adolescents represented in the UPUS corpus (compare Opsahl Reference Opsahl2009). As pointed out by Cornips & Gregersen (2017), there are certain difficulties associated with the establishment of a target norm with respect to young people’s linguistic practices, partly because their actual use may cut across lines stipulated by standard norms. They may also be establishing a norm of their own. Nonagreement in table 2 is a descriptive term covering the cases where the adolescents’ gender marking deviates from the Bokmål standard, as illustrated in 2 below.

Table 2. Gender-marked noun phrases produced by UPUS adolescents compared to the Bokmål norm.

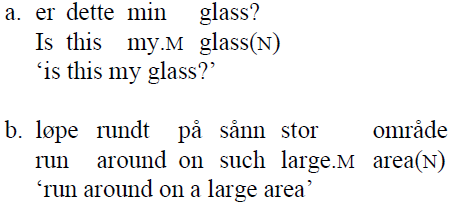

According to Faarlund et al. (Reference Faarlund, Lie and Vannebo1997:152), the expected proportional representation of Bokmål nouns by gender—counting all the nouns that may be marked as feminine—is as follows: Approximately 40% masculine, 30% feminine, and 25% neuter. Even when taking into account that the distribution of all available nouns may differ from the distribution of nouns found in the conversations, it is striking that the UPUS adolescents produced considerably more noun phrases marked as masculine (66.4% versus 40%). The cases of nonagreement are also adding to the impression of a masculine or common gender dominance. In several cases, neuter nouns were treated as masculine nouns, as in 2.

(2)

The masculine dominance becomes even clearer in the noun phrases with an indefinite article as their only gender marker. Leaving out instances of fixed expressions such as et eller annet ‘one or the other’ and på en måte ‘in a way’, 144 noun phrases introduced by the indefinite articles en, ei or et remain (or, to be more precise, en or et, because none of the 22 adolescents used the feminine indefinite article ei (Opsahl & Nistov 2010:60). 19 of these are introduced by the neuter indefinite article in a conventional fashion, 115 are marked as masculine in a conventional fashion, and 19 potentially feminine nouns are marked as masculine (common) with the indefinite article en, in line with the general tendency reported in other studies of the Oslo dialect (Lødrup Reference Lødrup2011). A search in the youngest age group in the NoTa corpus delivers only 24 instances of ei, and as many as 2,356 of en. In the case of the UPUS adolescents, 11 cases of nonconventional use of indefinite articles are found. With one exception, these are cases where neuter nouns are combined with the masculine determiner en, in examples such as en(m) maleri(n) ‘a painting’ (compare Opsahl Reference Opsahl2009:91).

The UPUS corpus reveals another feature characteristic of young people’s speech, namely, the use of sånn ‘such’. The use of sånn has increased among young speakers, including those outside of multiethnic neighborhoods (Lie 2008:92, Ekberg et al. Reference Ekberg, Opsahl, Wiese, Nortier and Svendsen2015). In addition to developing a new pragmatic function as a focus marker, in parallel with similar markers in Swedish and German, sånn seems to be grammaticalizing into a determiner, hence competing with the traditional indefinite articles (Ekberg et al. Reference Ekberg, Opsahl, Wiese, Nortier and Svendsen2015). This can be seen in example 2b, where sånn is chosen over the neuter variant sånt.

A tendency to overgeneralize the masculine gender is typical of many speakers learning Norwegian as their second language (Ragnhildstveit Reference Ragnhildstveit2018). There is no direct correlation, however, between the language backgrounds of the speakers and the cases of nonconventional gender marking. The girl who produced the utterance in 2a, for instance, was born in Norway to Norwegian-born parents. She expresses a positive attitude toward the multiethnic neighborhood of which she is a part, and she has several other features mentioned above in her linguistic repertoire as well (Opsahl & Nistov 2010). The deviations from standard norms are found primarily in in-group settings. Even though the examples showing how the masculine conquers the neuter domain are few, they are meaningful: Nonconventional gender marking is part of a certain stylistic practice. As was the case with the written Bokmål examples in the previous section, it is the interplay between gender and other linguistic (and nonlinguistic) features that together are involved in what may be seen as an enregisterment process (Agha Reference Agha2003, Eckert Reference Eckert2008).

The UPUS corpus is now itself in its teens, and no large-scale follow-up studies have yet been conducted on the linguistic practices in multiethnic neighborhoods in Norway. However, there are several observations pointing toward the continuous existence of a style or register characterized by many of the same features as described in the UPUS data. For example, in widely used high-school textbooks, multiethnolectal speech styles are discussed alongside more traditional dialects (Opsahl & Røyneland 2016). Furthermore, in 2017, Zeshan Shakar wrote a highly acclaimed, bestselling novel Tante Ulrikkes vei [Aunt Ulrikke’s Road] about two boys growing up in the northeastern multiethnic part of Oslo. The language use of one of the two protagonists in the novel, Jamal, in many ways closely resembles the one described in the UPUS project. In addition to expressing a strong affinity to hip-hop culture and pride in belonging to his local neighborhood, he uses the linguistic features typical of a multiethnolectal speech style. For example, he uses sånn as a focus marker and overgeneralizes the masculine gender to neuter nouns (see the examples in 3).

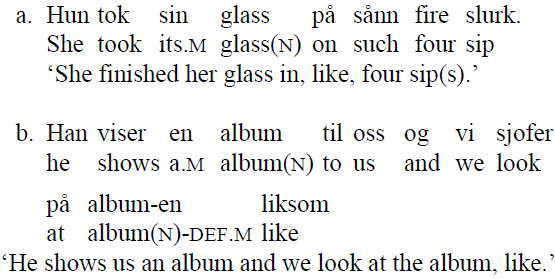

(3)

Zeshan Shakar has written a novel, and a work of fiction should not be treated as a scientific study of (one of the) modern Oslo dialect(s). At the same time, the novel contains a realistic representation of one of the Oslo dialects, and it is fair to say that the multiethnolectal speech style, as described in the UPUS project, still is an available resource for expressing—or in Shakar’s case portraying—certain personae. One of the features indexing the relevant meaning is nonconventional gender marking, but the cases of nonagreement are not causing the total breakdown neither of the gender system nor of declension classes as such. The definite suffix is for the most intact, as shown in 4.

(4)

Let me now turn to language contact in the northern part of Norway. Conzett et al. (Reference Conzett, Johansen and Sollid2011) and Sollid et al. (2014) studied contact between the Finno-Ugric languages Sámi and Kven without gender on the one hand, and Norwegian, with gender marking, on the other. In this language contact situation, they found several traces of unsystematic variation and simplification of the three- or two-gender system of Norwegian, but overall, both systems still stand. Noun inflection in the contact varieties of Norwegian is very similar to the other northern varieties of the Norwegian language, and nonagreement involving traditionally masculine or neuter nouns (similar to the examples in 2) is no more than a marginal phenomenon. The number of nouns displaying nonagreement is, in fact, fascinatingly similar to the number of nonagreement examples in the UPUS data (see table 2), as they amount to 2.6% of the cases. Neither the multiethnic, urban speech style nor the northern contact varieties’ gender systems are affected in their foundations, however, and they both have a noun inflection system similar to traditional varieties. Rather than undergoing simplification and/or dissolution, the gender category seems to be characterized by stability, as Sollid et al. (2014) claim. The cases of nonagreement shown in earlier studies from northern Norway may be “considered characteristic of a Norwegian contact variety in formation, whereas our informants […] represent the phase of stabilization” (Sollid et al. 2014:191). The numbers are small, but, according to Sollid et al. (2014:200), the gender nonagreement involving masculine and neuter receives metalinguistic attention in both northern contact communities and elsewhere. Hence, using masculine agreement marking on neuter nouns may index both a minority language background and a specific sociogeographical belonging.

2.4. Gender, Sexual Identity, and Semantics

Grammatical gender has played a role in negotiating sexual identities and contesting heteronormativity. One example of the role of grammatical gender in negotiating sexual identities is found in the 1979 novel by Gudmund Vindland Villskudd—sangen til Jens [Wild Shot—the Song for Jens]. This novel played a significant role in educating the general Norwegian public about the homosexual lifestyle and in promoting recognition and acceptance of love between two people regardless of their gender and sexual orientation. On several occasions throughout the novel, the author uses feminine gender marking to create a particular male image. This strategy resembles the one described in Podesva’s studies on regional accent features used to evoke a particular brand of a diva or partier persona (Podesva Reference Podesva2011). More importantly, semantically motivated gender agreement makes it possible to contest—and eventually maybe even dissolve—stereotypical correlations between biological sex and grammatical gender. This deserves more research attention in the future.

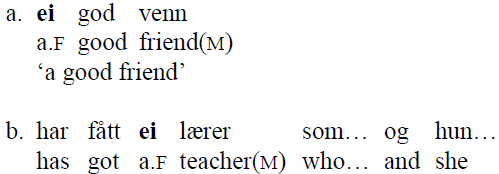

Enger (Reference Enger, Bonami, Boyé, Dal, Giraudo and Namer2018) points to instances of semantically motivated gender agreement in his discussion of why traces of the feminine survive where they do in Norwegian. For example, the nouns venn ‘friend’ and lærer ‘teacher’ in 5 are masculine, so one would expect the masculine determiner en. Instead, the feminine article ei is used.

(5)

Such examples are rare, but they exist, and, according to Enger (Reference Enger, Bonami, Boyé, Dal, Giraudo and Namer2018:242), they are not random: “They relate to nouns denoting humans, and whenever the feminine is employed, it refers to females.” However, even if the nouns change the attributive determiner from en to ei, they do not change the suffix -en to -a. Enger seeks an explanation for this and many other cases where the feminine seems to have been ousted by the masculine (apart from the definite suffix; see table 1) in grammaticalization theory. He applies a revised version of Corbett’s Agreement Hierarchy, concerning the “tightness” of grammatical relations (Enger Reference Enger, Bonami, Boyé, Dal, Giraudo and Namer2018:243). From a somewhat different angle, he arrives at the conclusion similar to the one in Rodina & Westergaard’s acquisition study (2013), also pointed out by Sollid et al. (2014). They quote Bybee (Reference Bybee1985), who proposes that the more closely a feature is tied to a lexical root, the more resistant it is to reduction. This idea also resembles the one expressed in Cornips & Gregersen 2017.

2.5. Gender and Pragmatics

Gender involves the interaction of morphology, syntax, semantics, and phonology (Lohndal & Westergaard 2016:1). To this already complex category one may add pragmatics. In this section, I focus on the feminine form lita and show that it seems to have taken on a role of a pragmatic marker.

In section 2.1, I showed that there is syncretism between the masculine and feminine in adjectives. There is only one exception to this pattern today, namely, the adjective liten (m) –lita (f) –lite (n) ‘small’. Note, however, that there are few instances of the feminine form lita in the spoken language corpora mentioned earlier. The feminine indefinite article ei is also more or less absent among young speakers. These observations further suggest that a two-gender system is taking over in Oslo, as in several Norwegian dialects.

Yet, over the last couple of years, several examples of ei and lita—typically pronounced with a short vowel, litta—have arisen among speakers who are expected to be users of a two-gender system with neuter and common gender (Opsahl Reference Opsahl, Knut, Rødningen and Tangen2017, Fløgstad & Eiesland Reference Fløgstad and Eiesland2019). Interestingly, these feminine forms combine with what are traditionally considered masculine and neuter nouns. The former are particularly widespread, as in lita (f) tur (m) ‘small hike’. As opposed to Fløgstad & Eiesland (Reference Fløgstad and Eiesland2019), I do not interpret these data as gender shift. Rather, the loss of the feminine gender has created conditions for exaptation, that is, assignment of new functions to existing morphological material previously associated with gender marking (Lass Reference Lass1990). In my interpretation, ei litta now serves as a pragmatic marker more or less independent of the gender category.

The pragmatic marker (ei) litta often appears in combination with speech acts and situations where some sort of hedging is required (Opsahl Reference Opsahl, Knut, Rødningen and Tangen2017, Fløgstad & Eiesland Reference Fløgstad and Eiesland2019:58), typically as part of a politeness strategy. Examples of such speech acts are criticisms, compliments, requests, and expressions of thanks, which are included among what is known as face-threatening acts (Brown & Levinson 1987 [Reference Brown and Levinson1978]). There is no room for a detailed account of politeness theory in this paper, but the crucial point is that, on some level, such speech acts threaten the hearer’s and/or the speaker’s self-image. A request, for example, predicates a future act of the hearer, and hence restricts their personal freedom, whereas a compliment may restrict the hearer by anticipating a positive reaction.

One example of a request combined with ei litta comes from a recent Christmas commercial of the large Norwegian dairy company Tine. It features the popular folklore character Fjøsnisse, or Cowshed Goblin, who is furious that people stopped bringing him his traditional plate of porridge at Christmas. He is wondering whether ei (f) litta (f) porsjon (m) julegrøt ‘a small serving of Christmas porridge’ is too much to ask. An example of an expression of thanks is found in a conversation between a student and their supervisor discussing the pitfalls and challenges of fieldwork. The student openly appreciates the possibility to discuss moments of insecurity and is grateful for ei (f) litta (f) tips (n) ‘a small piece of advice’.

Both the request for porridge and the expression of gratitude involve significant issues for the speakers. If the tradition of the Fjøsnisse is forgotten, the Fjøsnisse himself vanishes, and if the student is unable to navigate through the challenges of fieldwork, they may fail. Still, the Fjøsnisse and the student chose a communicative strategy of downplaying the size or significance of the issue in question, framing it as something not involving too much effort from the hearer. I interpret this type of pragmatic hedging as the preservation of self-image, along the lines of Brown & Levinson (1987 [Reference Brown and Levinson1978]). This point may become clearer if one turns to some additional data:

(Ei) litta is particularly common in the social media context. For example, the hashtag littaselfie, which combines the feminine adjective form with the masculine noun selfie (‘self-portrait using the phone camera’), is added to self-portraits on platforms such as Facebook and Instagram. The phrase litta selfie generates several hundred hits in public Instagram profiles, as well as more than 1,000 Google hits. Similar examples have also been found in a large text corpus based on Norwegian web-texts (Fløgstad & Eiesland Reference Fløgstad and Eiesland2019). Another phrase easily traceable across several platforms is litta (f) tur (m) ‘small hike’ mentioned above, in the context of posts depicting hiking or other social activities (which, despite being downplayed with litta, often show spectacular sceneries). These cases may be interpreted along the same lines as the previous examples, as they may be seen as requests (for compliments), predicting a future act of the reader, which also involves the risk of the poster being judged and negatively evaluated. To mitigate this risk, people resort to pragmatic hedging, which is achieved through downplaying the quality or the significance of what they post. It is hypothesized that if the user downplays the quality or significance of the images, they feel that the reader would be less inclined to criticize them.

As for the source of the construction, it has generated some debate. It has been suggested that it was first used by some popular radio show hosts at the national broadcasting corporation, NRK. However, there is good reason to believe that the popularity of this construction increased when Noora, one of the characters in an immensely popular television show, SKAM, used the litta (tur) phrase (Opsahl Reference Opsahl, Knut, Rødningen and Tangen2017).

To conclude, the choice of a conspicuous form, such as the traditional feminine in a system where feminine forms have disappeared, may be an answer to the need for expressing, projecting, and negotiating particular personae, identities and relations in everyday interaction, including interaction through social media.

3. General Discussion and Concluding Remarks

Sometimes speakers make a conscious decision to use a particular linguistic feature; they may intentionally introduce new features or exaggerate existing ones in order to dissociate themselves from speakers of another variety. In particular, speakers can decide to use a certain gender marker, and sometimes this choice involves nonagreement. This phenomenon is referred to as hyperdialectism (Trudgill Reference Trudgill1986, Hinskens Reference Hinskens2014). However, hyperdialectism does not always involve a deliberate act on the part of the speaker. Hinskens (Reference Hinskens2014:136) distinguishes another type of hyperdialectism, when L2 speakers unintentionally overgeneralize morphologically conditioned or lexicalized rules.

Both types of hyperdialectism seem applicable to the situation within the Norwegian gender system as presented above: The first type of hyperdialectism emerges when the speaker makes a deliberate choice to adhere to a two-gender system to distance himself or herself from the radical, rural, local or some other indexical meaning associated with the feminine gender. The speaker may also decide to expand the masculine forms even further as part of a certain stylistic practice in urban youth settings. The second type emerges in contact situations that involve L2 speakers of Norwegian. Moreover, taking the sociolinguistic perspective outlined in the introduction seriously, it is hard—and maybe not even necessary—to draw a strict line between intentional and unintentional language use:

Any given construction of identity may be in part deliberate and intentional, in part habitual and hence often less than fully conscious, in part an outcome of interactional negotiation and contestation, in part an outcome of others’ perceptions and representations, and in part an effect of larger ideological processes and material structures that may become relevant to interaction. (Bucholtz & Hall 2005:606)

Many of the features found in the young urban varieties (see the UPUS data) and varieties emerging from the language shift in northern Norway resemble overgeneralizations made by L2 learners; furthermore, in both cases, L2 learners are part of the communities and engage in the local stylistic practices. However, as mentioned above, such features are found in the speech of both non-native and native Norwegian speakers. Therefore, they may not be classified as a strictly L2 phenomenon. Instead, I propose that one is dealing here with the first type of hyperdialectism, as defined in Hinskens Reference Hinskens2014, that is, the use of those features constitutes a deliberate choice on the part of the speaker. This interpretation underscores a theoretical point, which is the importance of the agency of speakers. The speakers themselves do the work of indexicality and enregisterment from within specific sociohistorical matrices.

At the same time, experimental studies have shown that the comprehension of gender as grammatically meaningful is affected before its production. Even when speakers produce three genders, they do not necessarily use gender cues to anticipate or predict upcoming linguistic material (Lundquist et al. Reference Lundquist, Yulia, Sekerina and Marit2016). In future research, to isolate the indexical value of a certain gender feature one may employ a combination of psycholinguistic experimental and socioethnographic methods that highlight the local sociohistorical context.

In the introduction, I mentioned how frequency of input has been put forward as an important explanatory factor for changes within the gender system. An interesting question, then, is whether or not the cases of nonagreement, such as the expansion of the masculine to neuter nouns or the novel use of ei litta, provide new input to an extent that gender as a grammatical category is in danger of disappearing. I find this an unlikely scenario: According to Cornips & Gregersen (2017:123), bilinguals do not differ qualitatively but only quantitatively from their monolingual age mates when it comes to the overuse of the indefinite common en with neuter nouns in Danish. Furthermore, even in situations of prolonged language contact with languages without gender, such as in the north of Norway, the gender system as a whole is not dissolving (Sollid et al. 2014). Parts of the gender system may still be indexically tied to identity categories.

One apparent exception to the stability of the gender category is American Norwegian, where the gender system seems to be affected by attrition, according to Lohndal & Westergaard (2016). Even in this case, however, it should be pointed out that there is a relationship between gender and social meaning. The nonsystematic agreement patterns characteristic of the American Norwegian variety may in fact be an important feature indexing the very existence of an American-Norwegian identity category.

The list of social meanings associated with grammatical gender presented above was not intended to be exhaustive; rather it provides examples of indexical meanings that speakers create using grammatical gender, and/or features previously associated with gender marking, as a linguistic resource to negotiate their identities. Each of these meanings deserves closer inspection. It would probably be a semiotic fallacy to claim that everything in language at any given point is always meaningful (Lass Reference Lass1990:100), but variation may be socially indexical. Recognizing the role of the agency of speakers, it is clear that grammatical gender cannot be fully understood without taking into consideration the interactional context at a micro-level; at a macro-level, one needs to consider the sociohistorical characteristics of regions with massive language contact. Whether one agrees with this claim or not, there is little doubt that sociolinguistic perspectives add more color to the overall picture of the mysteries of grammatical gender in Germanic.

DATA SOURCES

NAOB (Det Norske Akademis Ordbok [the Dictionary of the Norwegian Academy]). 2018. Oslo: Kunnskapsforlaget and Det norske akademi for språk og litteratur. Available at www.naob.no, accessed on November 13, 2019.

NoTa-Oslo: Norwegian Speech Corpus—the Oslo part. Available at http://www.tekstlab.uio.no/nota/oslo/english.html, accessed on July 1, 2019.

Shakar, Zeshan. 2017. Tante Ulrikkes vei. Oslo: Gyldendal. Vindland, Gudmund. 1979. Villskudd. Sangen til Jens. Oslo: Forfatterforlaget.